Abstract

Membrane transporters are integral membrane proteins that mediate the passage of solutes across lipid bilayers. These proteins undergo conformational transitions between outward- and inward-facing states, which lead to alternating access of the substrate-binding site to the aqueous environment on either side of the membrane. Dozens of different transporter families have evolved, providing a wide variety of structural solutions to achieve alternating access. A sub-set of structurally diverse transporters operate by mechanisms that are collectively named ‘elevator-type’. These transporters have one common characteristic: they contain a distinct protein domain that slides across the membrane as a rigid body, and in doing so it ‘drags” the transported substrate along. Analysis of the global conformational changes that take place in membrane transporters using elevator-type mechanisms reveals that elevator-type movements can be achieved in more than one way. Molecular dynamics simulations and experimental data help to understand how lipid bilayer properties may affect elevator movements and vice versa.

Keywords: membrane proteins, protein structure, transport

Introduction: moving barriers and elevators

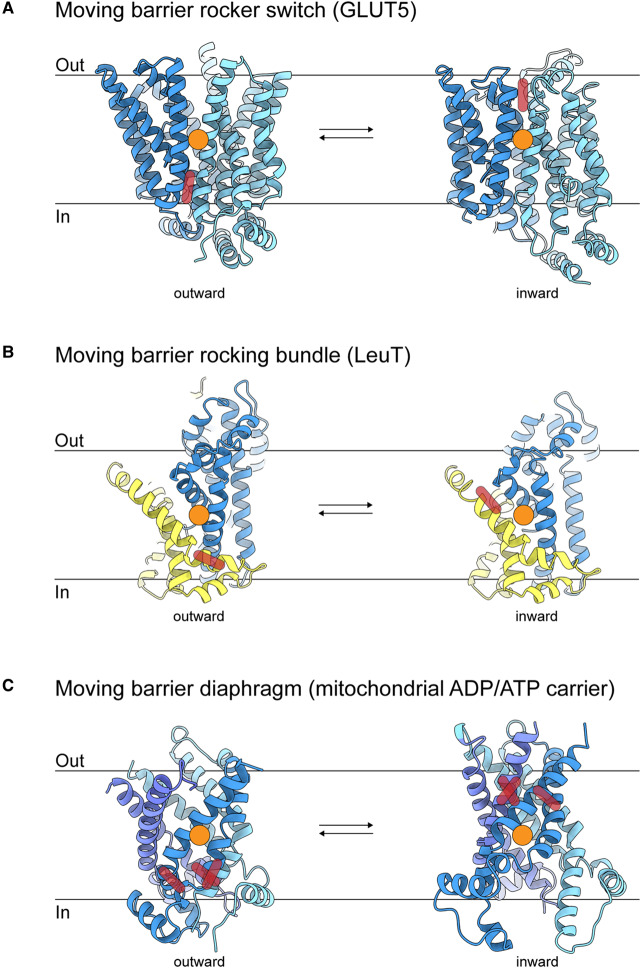

Structural studies of membrane transporters from diverse protein families have revealed that alternating access may by achieved in many ways (reviewed recently [1]). The so-called “moving barrier” mechanism is a frequently used solution (Figure 1). Proteins operating by this mechanism bind the transported substrate in a deep cavity, which is accessible to the aqueous environment from one side of the membrane only. A conformational change then closes off the access path to the binding site (gate closure), and opens up a new path to the other side of the membrane (gate opening). Moving barrier transporters thus work with two separate gates. Synchronization of opening and closing of the two gates is crucial: intermediate occluded states with both gates closed may be visited, but states with both gates open are prohibited. During the conformational transitions in the protein, the substrate remains bound at roughly the same position relative to the bilayer plane, until the conformational switching has been completed and a route to the aqueous solution on the opposite side of the membrane has opened. In many cases, the substrate-binding site is located halfway through the bilayer between two proteins domains that move around the substrate when switching between inward- and outward-facing states. The transport protein thus serves as a “moving barrier’. Prominent examples of proteins using a moving barrier mechanism include members of the major facilitator superfamily, in which two homologous protein domains swivel around the substrate as a rocker switch [2,3] (Figure 1a); the LeuT-fold proteins in which one protein domain moves as a rocking bundle relative to a fixed second (non-homologous) domain [4] (Figure 1b); and mitochondrial carriers, where three homologous domains pivot around the substrate in a concerted way as a diaphragm [5] (Figure 1c).

Figure 1. Non-elevator type transporters.

(a) moving barrier, rocker switch, exemplified by the fructose transporter GLUT5 with two protein domains (blue shades) rotating around substrate-binding site (orange circle) changing the barrier position (red bars) (PDB IDs for outward and inward states: 4YBQ and 4YB9).(b) moving barrier, rocking bundle, exemplified by the leucine transporter LeuT with transport domain (blue) moving relative to the scaffold domain (yellow). The substrate-binding site does not change its position relative to the membrane plane during the transition from outward to the inward state, but the barrier (red bar) does change (PDB IDs: 3TT1 and 3TT3). (c) the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier represents the moving-barrier, diaphragm mechanism, where three protein domains (blue shades) rotate around substrate-binding site changing the barrier position, indicated by the red bars (PDB IDs: 6GCI and 4C9H).

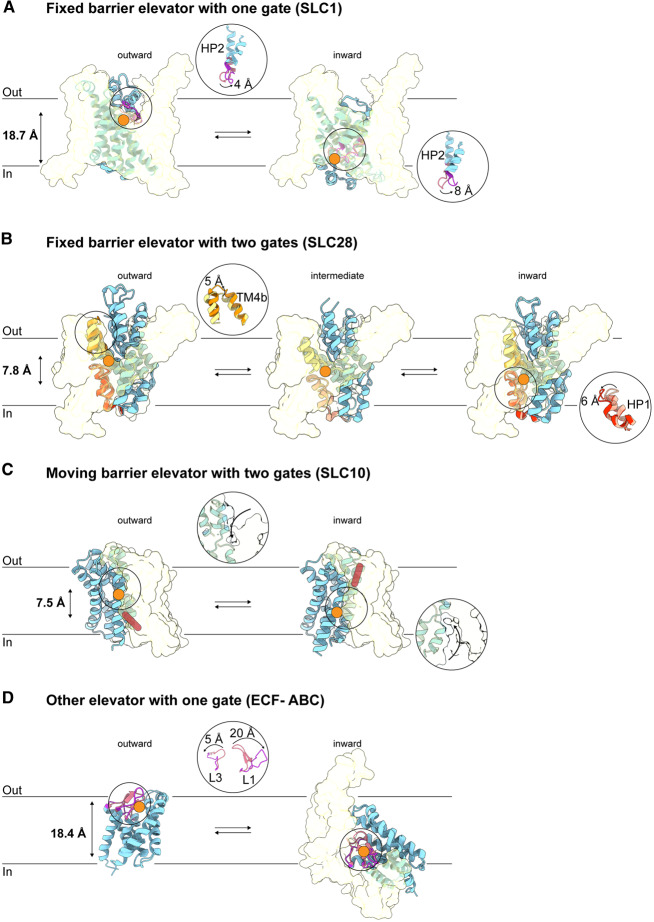

The elevator-type transport mechanism offers an alternative solution to achieve alternating access [1]. Proteins using this mechanism consist of a moving and fixed domain (often termed “transport” and “scaffold” domain, respectively). Switching between outward- and inward-facing states involves the sliding of the entire transport domain through the bilayer as a rigid body. In contrast with proteins using a moving-barrier mechanism, the substrate-binding site translocates some distance across the bilayer during transport along with the transport domain (Figure 2). Because of the displacement of the substrate the elevator mechanism has been described as “moving carrier’. Alternatively, the name “fixed barrier mechanism” has been proposed [1], but as we will discuss below, some elevator proteins may not have a fixed barrier. Therefore, we prefer the names “elevator-type” or “moving carrier” mechanism. It is noteworthy that the classification of a transporter mechanism as “moving barrier” or “moving carrier” is based solely on the structural changes that take place in the proteins during transport, and that it does not have predictive value for the transporter's substrate specificity, coupling ion specificity (in secondary active transporters), or for the kinetic mechanism.

Figure 2. One- and two-gate elevators.

(a) fixed barrier elevator with one gate. Neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 (SLC1 family) (transport domain as blue ribbon; scaffold domain as yellow transparent surface) uses helical hairpin HP2 as a gate in both the outward state (it moves by 4 Å form the light pink closed (PDB ID: 6MPB) to the bright pink open conformation (PDB ID: 6MP6)) and in the inward state (8 Å movement from closed (PDB ID: 6GCT) to open position (PDB ID: 6RVX)). ASCT2 translocates substrate (orange circle) relative to the membrane plane during transport (distances are indicated on the left), keeping the same contact (barrier) with the stable scaffold domain. (b) fixed barrier elevator with two gates. Concentrative nucleoside transporter CNT (SLC28 family) uses TM4b as an extracellular gate (5 Å movement from closed yellow (PDB ID: 5U9W, chain C) to open orange state (PDB ID: 5L2A, chain C)) and HP1 as an intracellular gate (6 Å movement from light pink closed (PDB ID: 5L26, chain A) to red open state (PDB ID: 5L27, chain A)). CNT is the only elevator transporter, for which multiple intermediate conformations have been resolved structurally, one of which is shown (PDB ID: 5L24, chain C). (c) moving barrier elevator with two gates. The bile acid transporter ASBT (SCL10 family) provides access to the binding site (indicated by arrows within the circle) using bundle movements of the transport domain (PDB ID: 4N7X and 3ZUX), during which barrier (red bar) is changing. (d) other elevator with one gate. Energy coupling factor folate transporter ECF-FolT (ECF-type (type III) ABC importer) has loop 1 (L1) and loop 3 (L3) in the S-component (blue ribbon) that provide access to the substrate-binding site from the extracellular (PDB ID: 5D0Y) and the intracellular side (PDB ID: 5JSZ). The EcfT subunit is in yellow transparent surface, and the ATPase subunits are omitted for clarity.

The first elevator-type mechanism was described in 2009 for the aspartate transporter GltPh [6], a member of the glutamate transporter or SLC1 (Solute Carrier 1) family, but the name “elevator” was not used until 2011 [7]. In recent years, elevator-type mechanisms have been proposed for numerous other proteins (Table 1). Many of the proteins shown in Table 1 are sodium-coupled secondary active transporters, but a sub-set of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, phosphotransferase system (PTS) transporters and unclassified transport proteins also appear to use elevator-type mechanisms. The abundant representation of secondary active transporters in Table 1 may simply be a reflection of the large number of families of secondary transporters that have evolved [8]. In this review, we focus on the global structural changes that take place in elevator-type membrane transporters. We do not discuss the kinetics of switching between outward- and inward-facing states, which may depend on the occupancy of the solute-binding site, or binding of compounds to allosteric sites, such as co-transported ion(s) in secondary active transporters, or nucleotides in ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. For details of the intricate mechanisms of coupling of transport to co-ion translocation or ATP hydrolysis we refer to recent reviews [9–12].

Table 1. Available structures and characteristics of the transporters with proposed elevator-like transport mechanism.

| Protein | Outward-facing conformation (PDB accession code) | Inward-facing conformation (PDB accession code) | Intermediate conformation (PDB accession code) | Oligomeric state | Protein family | Total substrate-binding site displacement (Å)1 | Vertical displacement (Å)1 | Number of helical hairpins | Substrate binding site location | Type of elevator | Method of structure determination | Topology of inverted repeats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCT2 | 6mp6[27] 6mpb[27] |

6gct[29] 6rvx[28] 6rvy[28] |

- | Trimer | SLC1 | 20.2 | 18.7 | 2 | within the transport domain | fixed barrier with one gate | cryo-EM, | present |

| GltTk | 4ky0[62] 5dwy[63] 5e9s[63] 6r7r[64] 6xwn[30] |

6xwr[30] 6xwo[30] 6xwp[30] 6xwn[30] |

6xwr[30] 6xwo[30] 6xwp[30] 6xwq[30] |

Trimer | SLC1 | 23.7 | 21.2 | 2 | within the transport domain | fixed barrier with one gate | X-ray, cryo-EM | present |

| GltPh | 1xfh[65] 2nww[66] 2nwl[66] 2nwx[66] 4izm[67] 4oye[68] 4oyf[68] 5cfy[68] 6ctf[58] 6bat[69] 6bau[69] 6bav[69] 6bmi[69] |

3kbc[6] 3v8f[70] 4p6h[68] 4p19[68] 4p1a[68] 4p3j[68] 4x2s[54] |

3v8g[70] | Trimer | SLC1 | 21 | 18 | 2 | within the transport domain | fixed barrier with one gate | X-ray | present |

| EAAT1 | 5llm[47] 5llu[47] 5lm4[47] 5mju[47] |

- | - | Trimer | SCL1 | 2 | within the transport domain | fixed barrier with one gate | X-ray | present | ||

| CNTNW | 5l2a[36] 5l2b[36] |

5l26[36] | 5l27[36] 5l24[36] 5u9w[36] |

Trimer | SLC28 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 2 | at the interface | fixed barrier with two gates | X-ray | present |

| vcCNT | - | 3tij[71] 4pb1[72] 4pb2[72] 4pd5[72] 4pd6[72] 4pd7[72] 4pd8[72] 4pd9[72] 4pda[72] |

- | Trimer | SLC28 | 2 | at the interface | fixed barrier with two gates | X-ray | present | ||

| ASBTNM | - | 3zux[73] 3zuy[73] |

- | monomer | SLC10 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 0 | at the interface | moving barrier with two gates | X-ray | present |

| ASBTYf | 4n7w[44] 4n7x[44] |

- | - | monomer | SLC10 | 8.7 | 7.5 | 0 | at the interface | moving barrier with two gates | X-ray | present |

| Bor1 | - | 5l25[74] 5sv9[75] |

- | dimer | SLC4 | 0 | at the interface | X-ray, electron crystallography of 2D crystals | present | |||

| AE1 | 4yzf[39] | comp.model[15] | - | dimer | SLC4 | 11[15] | 8[15] | 0 | at the interface | X-ray, modelling | present | |

| UraA | - | 3qe7[41] 5xls[40] |

- | dimer | SLC23 | 0 | at the interface | X-ray | present | |||

| UapA | - | 5i6c[76] | - | dimer | SLC23 | 0 | at the interface | X-ray | present | |||

| SLC26Dg | - | 5da0[77] | - | dimer | SLC26 | 6[42] | 0 | at the interface | X-ray | present | ||

| BicA | - | 6ki1[43] 6ki2[43] |

- | dimer | SLC26 | 6[43] | 0 | at the interface | X-ray, cryo-EM | present | ||

| MtrF | - | 4r1i[78] | - | dimer | AbgT | 2 | at the interface | X-ray | present | |||

| YdaH | - | 4r0c[79] | - | dimer | AbgT | 2 | at the interface | X-ray | present | |||

| KpCitS | 5x9r[80] 5xas[80] |

4bpq[81] 5xat[80] 5xar[80] 5xas[80] |

- | dimer | 2HCT | 14.6 | 13.9 | 2 | at the interface | fixed barrier | X-ray, electron crystallography of 2D crystals | present |

| SeCitS | 5a1s[38] | 5a1s[38] | - | dimer | 2HCT | 17.3 | 15.2 | 2 | at the interface | fixed barrier | X-ray | present |

| VcINDY | comp.model[14] | 4f35[82] | - | dimer | DASS | 15[14] | 2 | at the interface | X-ray, modelling | present | ||

| EcNhaA | - | 1zcd[83] 4au5[84] 4atv[84] 3fi1[85] |

- | dimer | Na+/H+ antiporters | 10[86] | 0 | at the interface | moving barrier with two gates | X-ray, electron crystallography of 2D crystals | present | |

| TtNapA | 4bwz[86] 5bz3[48] |

5bz2[48] | - | dimer | Na+/H+ antiporters | 9.6 | 8.6 | 0 | at the interface | moving barrier with two gates | X-ray | present |

| MjNhaP1 | - | 4czb[87] | - | dimer | Na+/H+ antiporters | 0 | at the interface | electron crystallography of 2D crystals | present | |||

| PaNhaP | - | 4cz8[88] 4cz9[88] 4cza[88] |

- | dimer | Na+/H+ antiporters | 0 | at the interface | X-ray | present | |||

| bcMalT | 5iws[32] | 6bvg[33] | - | dimer | PTS system | 11.5 | 9 | 2 | at the interface | fixed barrier | X-ray | present |

| bcChbC | - | 3qnq[34] | - | dimer | PTS system | 2 | at the interface | X-ray | absent | |||

| ecUlaA | 4rp8[89] 4rp9[89] |

- | - | dimer | PTS system | 18.8 | 16.6 | 4 | at the interface | moving barrier | X-ray | present |

| pmUlaA | - | 5zov[90] | - | dimer | PTS system | 18.8 | 16.6 | 4 | at the interface | moving barrier | X-ray | present |

| TtCcdA | 5vkv[17] | comp.model[17] | - | monomer | LysE | 12[17] | 0 | at the interface | moving barrier | NMR, modelling | present | |

| ECF transporters | 4m58[91] 4m5c[91] 4m5b[91] |

5x3x[92] 5x41[92] |

- | Protein complex | Group I ECF ABC | 0 | within the transport domain | one-gate elevator | X-ray | absent | ||

| ECF transporters | 5d0y[35] 3p5n[93] 3rlb[94] 4dve[95] 5kbw[96] 5kc0[96] 5kc4[96] 4mes[97] 4mhw[97] 4muu[97] 4pop[97] 4pov[97] 4n4d[97] 4z7f[98] 6ffv[99] |

5jsz[35] 5d3m[35] 6fnp[100] 4rfs[101] 4huq[102] 4hzu[103] |

- | protein complex | Group II ECF ABC | 22.1 | 18.4 | 0 | within the transport domain | one-gate elevator | X-ray | absent |

See text for definitions and abbreviations.

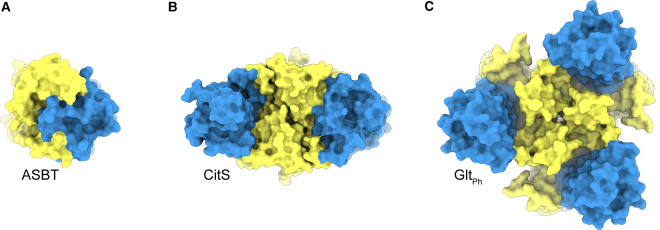

Common characteristics of elevator-type transporters

In proteins using the elevator mechanism, the substrate moves some distance across the membrane during the conformational switching. In Table 1, the extent of the movement is indicated as the “vertical distance’, the displacement of the substrate in z-direction if the membrane plane is defined as the xy plane. In many cases, the domain movement is more complex than a simple translation, and the total distance over which the substrate is displaced is larger than the vertical distance (Table 1). Structurally, elevator-type membrane transporters show large diversity, indicating that the vertical movement can be realised in multiple ways, but many of the proteins have some characteristics in common. First, the transported substrates bind exclusively, or predominantly, to the transport domain, which is a prerequisite for joined movement of the transport domain and substrate, relative to the rigid scaffold domain. Second, in many cases the transport domain contains structural elements named helical hairpins (HPs) that form the gates, which must be open to allow access of the substrate to the bindings site, and closed to make the elevator movement possible. An open gate prevents sliding of the transport domain relative to the scaffold domain because of steric incompatibility. Third, almost all proteins using elevator transport mechanisms have a membrane topology with inverted repeats [13], resulting in internal pseudosymmetry, which has been used to model the outward-facing conformation based on an inward-facing structure or vice versa [14–17]. Finally, elevator-type transport proteins are often homodimers or homotrimers. Subunit contacts in the oligomers are made exclusively by the scaffold domains, while the transport domains are located peripherally (Figure 3). It is not entirely clear what is the functional significance of the oligomeric state. For homotrimeric members of the glutamate transporter family, it has been shown that the three protomers function independently [18–25], but it is possible that cooperativity may occur in other protein families.

Figure 3. Oligomeric state of elevator transporters.

(a) monomeric bile acid transporter ASBT (PDB ID: 3ZUX), (b) dimeric citrate transporter SeCitS (PDB ID: 5A1S) and (c) trimeric glutamate transporter GltPh (PDB ID: 2NWW) viewed from the extracellular side of the membrane. Transport domains in blue, scaffold domains in yellow.

Despite these similarities, global elevator movements and local gating motions vary widely between different protein families (Table 1). Using currently available structural data, elevator mechanisms can be classified into three types with pronounced differences in the way gating is achieved. The classification is based on proteins for which structures are available of multiple conformational states. For many of the proteins in Table 1, only a single structure has been solved, and therefore it is not yet possible to unambiguously classify them.

Fixed barrier elevator with one gate

The glutamate transporter (SLC1) family of solute transporters is structurally well-characterized with 39 available structures of four different family members: the prokaryotic sodium-dependent aspartate transporters GltPh and GltTk, the human sodium- and potassium-dependent glutamate transporter EAAT1 (Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter 1), and the human neutral amino acid exchanger ASCT2 (Alanine Serine Cysteine Transporter 2) (Table 1 and reviewed in [26]) . While GltPh is the prototypical elevator transporter, ASCT2 is the first SLC1 member, for which four key conformations have been resolved structurally: outward-open, outward–occluded [27], inward-open [28] and inward–occluded [29]. We will use these structures to describe the one-gate, fixed barrier elevator movement (Figure 2a).

Like all members of the SLC1 family, neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 is a homotrimer. Each monomer consists of 8 transmembrane segments (TMs) that form a scaffold domain (TM1–2, TM4–5) and a transport domain (TM3, TM6–8). The transport domain additionally contains two helical hairpins (HP1 and HP2). In the outward-facing states the substrate-binding site is close to the extracellular side of the membrane, and the only difference between open and closed conformations is the position of HP2, which works as a gate to provide access to the binding site from the extracellular aqueous environment [27] (Figure 2a). When the gate is closed, the transported substrate is occluded within the transport domain, which makes the elevator movement possible. The binding site relocates by a distance of ∼19 Å perpendicular to the membrane plane between the outward- to the inward-facing orientation. Strikingly, HP2 was also found to be the gate on the intracellular side, hence the name one-gate elevator mechanism [28]. HP1 plays a role in substrate coordination in the binding site, but in contrast with HP2, it does not change its conformation during the transport cycle. The scaffold domain has two highly tilted helices (TM2 and TM5) along which the transport domain slides. These helices determine the minimal distance that the substrate-binding site must travel, and have been named the fixed barrier [1].

The fixed barrier elevator mechanism with one gate is likely conserved among the SLC1 family, as evidenced by recent single particle cryo-EM structures of GltTk [30], and molecular dynamics simulations of GltPh [7]. Fixed barrier elevators with one gate may also occur in other families of transporters, for which the number of structurally resolved states is not as large as for the SLC1 family. Transporters of the Phosphotransferase System (PTS), which are responsible for the uptake and phosphorylation of carbohydrates and other compounds such as ascorbate (reviewed in [31]) have characteristic elevator elements, such as transport and scaffold domains, HP gates, and homo-oligomer architecture. Structures of MalT [32,33] and ChbC [34] indicate that they use a fixed barrier and most likely a single gate.

ATP-binding Cassette (ABC) transporters do not use elevator-type mechanisms of transport, with the exception of the non-canonical subfamily of ECF (energy-coupling factor) transporters. ECF transporters are involved in uptake of vitamins or other micronutrients (reviewed in [11]). Two sub-types exist (Group I and II) which may differ in the mechanistic details, but the ensemble of available structural information is consistent with elevator-type behaviour in all ECF transporters. ECF transporters make use of an integral membrane subunit named the S-component that binds the transported substrate on the extracellular side of the membrane (Figure 2d). In many cases, access to the binding site is controlled by two loops, which act as gate (loop 1 and loop 3). In the bound state, with closed gate, the substrate is occluded and the S-component can “topple over” in the membrane, which brings the substrate-binding site to the cytoplasm. In the toppled state the same loops 1 and 3 can move to expose the binding site to the cytoplasm (similar to a one-gate elevator). The S-component may be considered as the equivalent of the transport domain, whereas the counterpart of the scaffold domain is a second integral membrane subunit, named EcfT or T-component (Figure 2d). The use of separate subunits instead of linked domains provides extra functionality, as dissociation and association are part of the transport cycle in some ECF transporters [35]. The EcfT subunit is additionally associated with ATPase subunits for allosteric coupling of the conformational changes to ATP binding and hydrolysis, which are the hallmark of ABC transporters.

Fixed barrier elevator with two gates

The concentrative nucleoside transporter CNT (a member of the SLC28 family) is a homotrimer [36], with each monomer subdivided into a transport domain (TM1–2, TM4–5, TM7–8 and HP1, HP2) and a scaffold domain (TM3 and TM6). In this case, the binding site for the nucleoside is located at the interface between scaffold and transport domains, but most of the interactions with the substrate come from the residues in the transport domain. CNT uses different gates on the extra- and intracellular sides [36] (Figure 2b). Comparison of structures of CNT in outward-open and outward-closed states revealed different conformations of TM4b, suggesting that this half-TM is an extracellular gate. On the intracellular side, HP1b is the movable element, which gates access to the binding site. The transitions between the outward- and inward-facing states involve a ∼8 Å translocation of the substrate-binding site (perpendicular to the membrane plane), in which it passes a fixed barrier formed by TM3 and TM6 of the scaffold domain. CNT is the only elevator transporter, for which multiple intermediate conformations, where the position of transport domain is distributed between the inward and outward states, have been resolved structurally.

It is possible that the location of the binding site between two domains in CNT necessitates the use of two gates, whereas an occluded binding site within the transport domain, as found in SLC1 transporters, may allow the use of a single gate. Most of the transporters with proposed elevator-like transport mechanisms have substrate-binding sites positioned at the interface of two domains (Table 1). Transporters of AbgT family [37] and the structurally related Na+/succinate transporter VcINDY [14] (DASS family), the Na+/citrate transporter SeCitS [38] (2HCT family), anion exchanger 1 (AE1), a member of SLC4 family [39] and the structurally related uracil:proton symporter UraA [40,41] from SLC23 family (seven transmembrane segment inverted repeat [42]), and bicarbonate transporter BicA [43] of the SLC26 family are organized in two domains (transport and scaffold) and bind the substrate at the domain interface. All of these proteins may use an elevator mechanism with fixed barrier and two gates [37], but additional structural characterization is needed to classify the gating mechanism of these transporters.

Moving barrier elevator with two gates

The bile acid transporter ASBT, and structurally related sodium-proton antiporters have 10 and 13 transmembrane helices respectively, with a transport domain (also called core domain) consisting of TM3–5, TM8–10 in ASBT (TM3–5, TM10–12 in sodium-proton antiporters), and a scaffold domain (TM1–2, TM6–7 in ASBT or TM1–2, TM7–9 in sodium-proton antiporters). Despite the movement of the substrate-binding site across the membrane during sliding of the transport domain relative to the scaffold (the hallmark of the elevator mechanism), ASBT does not have a fixed barrier (Figure 2c). Thus, this transporter combines an elevator movement with a moving barrier, which is a typical feature of non-elevator-type mechanisms (Figure 1) [44]. Unlike most other elevator transporters, ASBT and the related sodium-proton antiporters NapA and NhaA do not have helical hairpins. Possibly HPs are suitable for gating when a fixed barrier is used, but are not required for moving barrier elevators (Figure 2c).

ASBT is exceptional among elevator-type transporters because it is a monomeric protein. Another monomeric transporter, for which an elevator mechanism has been postulated, is CcdA [17]. CcdA is the smallest elevator-type protein and is involved in the transport of reducing equivalents from the cytoplasm to the extracellular environment, by using a pair of cysteine residues that can be oxidized to form a disulfide bridge. The protein consists of six transmembrane helices, which are organized in two inverted structural repeats [17]. Comparison of the outward-facing conformation, solved using NMR spectroscopy, and inward-facing conformation, which was computationally modelled using information from the inverted topology, showed that protein forms a unique “O-shaped scaffold” in the centre of which TM1 and TM4 may move as an elevator between inward- and outward-facing states with the active-site cysteines bridging a distance of 12 Å [17]. Structural information on CcdA is still very limited, and further work is required to confirm the elevator mechanism.

Lipid environment and allosteric inhibition

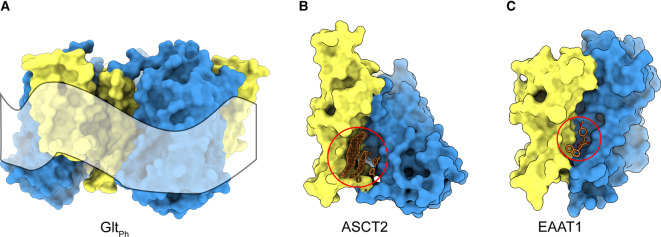

It has been noticed that the TMs of the scaffold domains of many elevator-type transporters are shorter than those in transport domains, and often highly tilted [1]. As a consequence, the distance between the external and internal aqueous solutions is substantially smaller than the thickness of the bulk bilayer. Such thinning not only reduces the extent of elevator movement required to transfer the substrate between the aqueous solutions on either side of the membrane, but may also induce membrane distortion, which in turn could facilitate the sliding movement of the transport domain. Molecular dynamic simulations of ECF transporters in a lipid bilayer predict possible membrane distortion near the EcfT scaffold, which might facilitate toppling of the S-component when it is near the scaffold [11,45]. Recent MD simulations of a lipid bilayer around GltPh show different extents of membrane deformation depending on the position of the transport domain [46] (Figure 4a). Protomers of GltPh in the outward-facing state induce very little local membrane curvature [46], but the lipid bilayer strongly bends around protomers in the inward-facing state. The energetic penalty of such deformation may be balanced by specific protein–lipid interactions.

Figure 4. Lipids and elevator transporters.

(a) deformation of the lipid bilayer around glutamate transporter GltPh (PDB ID: 3KBC), when all protomers are in the inward-facing state (adapted from ref. [46]). (b) non-protein densities (orange mesh) observed in the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 cryo-EM map (EMD-10016) are located at the interface of the transport (blue) and scaffold (yellow) domains and highlighted with a red circle (PDB ID: 6RVX). (c) allosteric inhibitor UCPH101 (orange sticks) in excitatory amino acid transporter EAAT1 (PDB ID: 5LLM).

Most structures of elevator-type transporters have been determined in the absence of a lipid bilayer, using detergent-solubilized proteins, which precludes accurate analysis of the protein–lipid interface. Nonetheless, these structures can provide indications of specific lipid-binding sites (Figure 4). For example, many non-protein densities were found in structures of ASCT2 determined by single particle cryo-electron microscopy (Figure 4b). These densities likely correspond to phospholipid molecules or cholesterol, although unambiguous identification was not possible at the attained resolution. The observed densities were located around the entire perimeter of the scaffold domain, also in the space between transport and scaffold domains, and close to the substrate binding site [28,29]. Lipids binding at these positions could be important for protein stability and might allosterically affect protein activity. A crystal structure of EAAT1 in the presence of the allosteric inhibitor UCPH101 demonstrated that the inhibitor's binding site is located between transport and scaffold domains [47], exactly where a putative cholesterol molecule was observed in ASCT2 [27–29] (Figure 4c). Also in other families of elevator-type transporters, lipids were found to intercalate between the scaffold and transport domains [38,48]. These observations indicate that specific lipid–protein interactions might affect elevator-like movements of the transporter, and that lipid-binding sites may be targeted for drug design.

In only very few cases have the effects of the lipid environment been studied experimentally. In GltPh the relation between lipid composition and transport activity was studied in proteoliposomes. The activity of GltPh was higher in liposomes containing the non-bilayer lipid Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), than in liposomes composed of Phosphatidylcholine (PC) [49]. This effect may be caused by specific interactions between the protein and lipid headgroups, or by colligative properties of the bilayer such as lipid disorder, both of which could affect the elevator-type movements. For ASCT2, glutamine uptake activity in proteoliposomes was enhanced by the presence of cholesterol [29], but again it has not been established whether this effect is due to binding of cholesterol at specific sites, or to colligative effects such as thickness or fluidity. Lipid interactions are also essential for dimer stability of NhaA, which falls apart to monomers in the presence of high detergent concentrations, but is assembled back if cardiolipin is added [50]. In vivo, allosteric modulation by lipid molecules has been observed in Xenopus oocytes expressing EAAT4 that displayed increased glutamate-induced currents when arachidonic acid was added [51]. The presence of cholesterol was found to be crucial for functioning and localization of EAAT2 [52].

The above examples show that lipids may affect protein function directly via interactions with amino acid residues, which could accelerate or slow down transport domain movements or stabilize the scaffold domain in the membrane. In addition, colligative bilayer properties are likely to affect the functioning of elevator-type transporters, because the lipid–protein interface must rearrange substantially during transport. Finally, also the domain structure of the proteins may affect the bilayer morphology, and consequently elevator dynamics.

Perspectives

Importance of the field. Since the first description of an elevator-type transport mechanism for GltPh over a decade ago [6], a variety of protein folds have emerged that support elevator movements, not only in secondary active transporters but also in different transporter classes (Table 1). Many of these transporters are potential targets in pharmacological studies and understanding of their transport and gating mechanisms might help with the development of new drugs.

A summary of the current thinking. In elevator-type transport mechanisms, one protein domain brings the substrate-binding site from one side of the membrane to the other by sliding through the lipid bilayer. The extent of the elevator movement, ranging from 21 Å in GltTk to 7.5 Å in ASBT, and number of gating elements (one or two) vary between different proteins (Table 1).

Future directions. Local deformations of the lipid bilayer near elevator-type transporters, which were observed in MD simulations [46], can be studied experimentally by single particle cryo-electron microscopy, using transporters reconstituted in lipid environment [30], similar to what has been done for the lipid scramblase TMEM16 [53]. Also systematic analysis of the relationship between lipid composition, transport activity and dynamics (for instance by single molecule FRET methods [18,54]) will shed further light on the interplay between bilayer and protein. The gating behaviour might affect the order of binding and release of coupled ions and a substrate, and steady state and pre-steady state kinetic measurements may allow insight in the consequences of using one or two gates [55–61].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).

Abbreviations

- 2HCT

2-hydroxycarboxylate transporters

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- AbgT

p-aminobenzoyl-glutamate transporter

- AE1

Anion Exchanger 1

- ASBTNM

Neisseria meningitidis apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter

- ASBTYf

Yersinia frederiksenii apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter

- ASCT

Alanine Serine Cysteine Transporter

- bcChbC

Bacillus cereus chitobiose transporter

- bcMalT

Bacillus cereus maltose transporter

- BicA

bicarbonate transporter

- Bor1

boron exporter 1

- CNTNW

Neisseria wadworthii concentrative nucleoside transporter

- Cryo-EM

cryo-electron microscopy

- DASS

divalent anion/Na+ symporter

- EAAT

Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter

- ECF ABC

ECF-type (type III) ABC importers

- ECF

Energy Coupling Factor

- ECF-FolT

Energy Coupling Factor folate transporter

- EcNhaA

Escherichia coli Na+/H+ antiporter

- ecUlaA

Escherichia coli ascorbate transporter (‘utilization of l-ascorbate’)

- FRET

Förster Resonance Energy Transfer

- GltPh

Pyrococcus horikoshii glutamate transporter homologue

- GltTk

Thermococcus kadakarensis glutamate transporter homologue

- GLUT5

fructose transporter

- HP

helical hairpin

- KpCitS

Klebsiella pneumonia sodium-ion dependent citrate transporter

- LeuT

leucine transporter

- LysE

L-lysine exporter

- MD

molecular dynamics

- MjNhaP1

Methanococcus jannaschii Na+/H+ antiporter

- MtrF

antibiotic exporter (Multiple Transferable Resistance)

- NMR

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

- PaNhaP

Pyrococcus abyssi Na+/H+ antiporter

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- pmUlaA

Pasteurella multocida ascorbate transporter (‘utilization of l-ascorbate’)

- PTS

phosphotransferase system

- SeCitS

Salmonella enterica sodium-ion dependent citrate transporter

- SLC26Dg

Deinococcus geothermalis fumarate symporter

- TM

transmembrane

- TMEM16

lipid scramblase (TransMEMbrane protein)

- TtCcdA

Thermus thermophilus membrane electron transporter

- TtNapA

Thermus thermophiles Na+/H+ antiporter

- UapA

purine/H+ symporter

- UCPH101

2-amino-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-7-(naphthalen-1-yl)-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile

- UraA

uracil:proton symporter

- vcCNT

Vibrio cholera concentrative nucleoside transporter

- VcINDY

Vibrio cholera Na+/succinate transporter (‘I'm not dead yet’)

- X-ray

X-ray crystallography

- YdaH

antibiotic exporter

- SLC

solute carrier

- SLC26Dg

Deinococcus geothermalis fumarate symporter

- TM

transmembrane

- TMEM16

lipid scramblase (TransMEMbrane protein)

- TtCcdA

Thermus thermophilus membrane electron transporter

- TtNapA

Thermus thermophiles Na+/H+ antiporter

- UapA

purine/H+ symporter

- UCPH101

2-amino-4-(4-methoxyphenyl)-7-(naphthalen-1-yl)-5-oxo-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-4H-chromene-3-carbonitrile

- UraA

uracil:proton symporter

- vcCNT

Vibrio cholera concentrative nucleoside transporter

- VcINDY

Vibrio cholera Na+/succinate transporter (‘I'm not dead yet’)

- X-ray

X-ray crystallography

- YdaH

antibiotic exporter

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Open Access

Open access for this article was enabled by the participation of University of Groningen in an all-inclusive Read & Publish pilot with Portland Press and the Biochemical Society.

Author Contribution

A.A.G. and D.J.S. wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures.

References

- 1.Drew D. and Boudker O. (2016) Shared molecular mechanisms of membrane transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 85, 543–572 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yan N. (2015) Structural biology of the major facilitator superfamily transporters. Annu Rev Biophys 44, 257–283 10.1146/annurev-biophys-060414-033901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura N., Verdon G., Kang H.J., Shimamura T., Nomura Y., Sonoda Y. et al. (2015) Structure and mechanism of the mammalian fructose transporter GLUT5. Nature 526, 397–401 10.1038/nature14909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamashita A., Singh S.K., Kawate T., Jin Y. and Gouaux E. (2005) Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of Na+/Cl– dependent neurotransmitter transporters. Nature 437, 215–223 10.1038/nature03978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruprecht J.J., King M.S., Zögg T., Aleksandrova A.A., Pardon E., Crichton P.G. et al. (2019) The molecular mechanism of transport by the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier. Cell 176, 435–447.e15 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reyes N., Ginter C. and Boudker O. (2009) Transport mechanism of a bacterial homologue of glutamate transporters. Nature 462, 880–885 10.1038/nature08616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dechancie J., Shrivastava I.H. and Bahar I. (2011) The mechanism of substrate release by the aspartate transporter Glt Ph: insights from simulations. Mol. Biosyst. 7, 832–842 10.1039/c0mb00175a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bai X., Moraes T.F. and Reithmeier R.A.F. (2017) Structural biology of solute carrier (SLC) membrane transport proteins. Mol. Membr. Biol. 34, 1–32 10.1080/09687688.2018.1448123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmgren M.G. and Nissen P. (2011) P-type ATPases. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 40, 243–266 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y. (2013) Common folds and transport mechanisms of secondary active transporters. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 42, 51–72 10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rempel S., Stanek W.K. and Slotboom D.J. (2019) ECF-Type ATP-binding cassette transporters. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88, 551–576 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-111705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice A.J., Park A. and Pinkett H.W. (2014) Diversity in ABC transporters: type I, II and III importers. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 49, 426–437 10.3109/10409238.2014.953626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forrest L.R. (2015) Structural symmetry in membrane proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 44, 311–337 10.1146/annurev-biophys-051013-023008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulligan C., Fenollar-Ferrer C., Fitzgerald G.A., Vergara-Jaque A., Kaufmann D., Li Y. et al. (2016) The bacterial dicarboxylate transporter VcINDY uses a two-domain elevator-type mechanism. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 256–263 10.1038/nsmb.3166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ficici E., Faraldo-Gómez J.D., Jennings M.L. and Forrest L.R. (2017) Asymmetry of inverted-topology repeats in the AE1 anion exchanger suggests an elevator-like mechanism. J. Gen. Physiol. 149, 1149–1164 10.1085/jgp.201711836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crisman T.J., Qu S., Kanner B.I. and Forrest L.R. (2009) Inward-facing conformation of glutamate transporters as revealed by their inverted-topology structural repeats. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106, 20752–20757 10.1073/pnas.0908570106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y. and Bushweller J.H. (2018) Solution structure and elevator mechanism of the membrane electron transporter CcdA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 163–169 10.1038/s41594-018-0022-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erkens G.B., Hänelt I., Goudsmits J.M.H., Slotboom D.J. and Van Oijen A.M. (2013) Unsynchronised subunit motion in single trimeric sodium-coupled aspartate transporters. Nature 502, 119–123 10.1038/nature12538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruan Y., Miyagi A., Wang X., Chami M., Boudker O. and Scheuring S. (2017) Direct visualization of glutamate transporter elevator mechanism by high-speed AFM. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 1584–1588 10.1073/pnas.1616413114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grewer C., Balani P., Weidenfeller C., Bartusel T., Tao Z. and Rauen T. (2005) Individual subunits of the glutamate transporter EAAC1 homotrimer function independently of each other. Biochemistry 44, 11913–11923 10.1021/bi050987n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leary G.P., Stone E.F., Holley D.C. and Kavanaugh M.P. (2007) The glutamate and chloride permeation pathways are colocalized in individual neuronal glutamate transporter subunits. J. Neurosci. 27, 2938–2942 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4851-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koch H.P., Brown R.L. and Larsson H.P. (2007) The glutamate-activated anion conductance in excitatory amino acid transporters is gated independently by the individual subunits. J. Neurosci. 27, 2943–2947 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0118-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akyuz N., Altman R.B., Blanchard S.C. and Boudker O. (2013) Transport dynamics in a glutamate transporter homologue. Nature 502, 114–118 10.1038/nature12265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stolzenberg S., Khelashvili G. and Weinstein H. (2012) Structural intermediates in a model of the substrate translocation path of the bacterial glutamate transporter homologue GltPh. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 5372–5383 10.1021/jp301726s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang J., Shrivastava I.H., Watts S.D., Bahar I. and Amara S.G. (2011) Large collective motions regulate the functional properties of glutamate transporter trimers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 15141–6 10.1073/pnas.1112216108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arkhipova V., Guskov A. and Slotboom D.J. (2017) Analysis of the quality of crystallographic data and the limitations of structural models. J. Gen. Physiol. 149, 1091–1103 10.1085/jgp.201711852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X., Plotnikova O., Bonin P.D., Subashi T.A., McLellan T.J., Dumlao D. et al. (2019) Cryo-EM structures of the human glutamine transporter SLC1A5 (ASCT2) in the outward-facing conformation. eLife 8, 1–17 10.7554/elife.48120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garaeva A.A., Guskov A., Slotboom D.J. and Paulino C. (2019) A one-gate elevator mechanism for the human neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–8 10.1038/s41467-019-11363-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garaeva A.A., Oostergetel G.T., Gati C., Guskov A., Paulino C. and Slotboom D.J. (2018) Cryo-EM structure of the human neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 515–521 10.1038/s41594-018-0076-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arkhipova V., Guskov A. and Slotboom D.J. (2020) Structural ensemble of a glutamate transporter homologue in lipid nanodisc environment. Nat. Commun. 11, 998 10.1038/s41467-020-14834-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeckelmann J.-M. and Erni B. (2019) Carbohydrate transport by group translocation: the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphotransferase system. Subcell. Biochem. 92, 223–274 10.1007/978-3-030-18768-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCoy J.G., Ren Z., Stanevich V., Lee J., Mitra S., Levin E.J. et al. (2016) The structure of a sugar transporter of the glucose EIIC superfamily provides insight into the elevator mechanism of membrane transport. Structure 24, 956–964 10.1016/j.str.2016.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ren Z., Lee J., Moosa M.M., Nian Y., Hu L., Xu Z. et al. (2018) Structure of an EIIC sugar transporter trapped in an inward-facing conformation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 5962–5967 10.1073/pnas.1800647115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y., Jin X., Levin E.J., Huang H., Zong Y., Quick M. et al. (2011) Crystal structure of a phosphorylation-coupled saccharide transporter. Nature 473, 50–54 10.1038/nature09939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swier L.J.Y.M., Guskov A. and Slotboom D.J. (2016) Structural insight in the toppling mechanism of an energy-coupling factor transporter. Nat. Commun. 7, 11072 10.1038/ncomms11072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirschi M., Johnson Z.L. and Lee S.Y. (2017) Visualizing multistep elevator-like transitions of a nucleoside transporter. Nature 545, 66–70 10.1038/nature22057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vergara-Jaque A., Fenollar-Ferrer C., Mulligan C., Mindell J.A. and Forrest L.R. (2015) Family resemblances: A common fold for some dimeric ion-coupled secondary transporters. J. Gen. Physiol. 146, 423–434 10.1085/jgp.201511481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wöhlert D., Grötzinger M.J., Kühlbrandt W. and Yildiz Ö (2015) Mechanism of Na+-dependent citrate transport from the structure of an asymmetrical CitS dimer. eLife 4, 1–18 10.7554/eLife.09375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arakawa T., Kobayashi-Yurugi T., Alguel Y., Iwanari H., Hatae H., Iwata M. et al. (2015) Crystal structure of the anion exchanger domain of human erythrocyte band 3. Science 350, 680–684 10.1126/science.aaa4335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu X., Yang G., Yan C., Baylon J.L., Jiang J., Fan H. et al. (2017) Dimeric structure of the uracil:proton symporter UraA provides mechanistic insights into the SLC4/23/26 transporters. Cell Res. 27, 1020–1033 10.1038/cr.2017.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu F., Li S., Jiang Y., Jiang J., Fan H., Lu G. et al. (2011) Structure and mechanism of the uracil transporter UraA. Nature 472, 243–247 10.1038/nature09885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang Y.N. and Geertsma E.R. (2017) The novel class of seven transmembrane segment inverted repeat carriers. Biol. Chem. 398, 165–174 10.1515/hsz-2016-0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang C., Sun B., Zhang X., Huang X., Zhang M., Guo H. et al. (2019) Structural mechanism of the active bicarbonate transporter from cyanobacteria. Nat. Plants 5, 1184–1193 10.1038/s41477-019-0538-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou X., Levin E.J., Pan Y., McCoy J.G., Sharma R., Kloss B. et al. (2014) Structural basis of the alternating-access mechanism in a bile acid transporter. Nature 505, 569–573 10.1038/nature12811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faustino, I., Abdizadeh H., Souza P.C.T., Jeucken A., Stanek W.K., Guskov A. et al. (2020) Membrane mediated toppling mechanism of the folate energy coupling factor transporter. Nat. Commun. 11, 1763 10.1038/s41467-020-15554-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou W., Fiorin G., Anselmi C., Karimi-Varzaneh H.A., Poblete H., Forrest L.R. et al. (2019) Large-scale state-dependent membrane remodeling by a transporter protein. eLife 8, 1–32 10.7554/eLife.50576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Canul-Tec J.C., Assal R., Cirri E., Legrand P., Brier S., Chamot-Rooke J. et al. (2017) Structure and allosteric inhibition of excitatory amino acid transporter 1. Nature 544, 446–451 10.1038/nature22064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coincon M., Uzdavinys P., Nji E., Dotson D.L., Winkelmann I., Abdul-Hussein S. et al. (2016) Crystal structures reveal the molecular basis of ion translocation in sodium/proton antiporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 248–255 10.1038/nsmb.3164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McIlwain B.C., Vandenberg R.J. and Ryan R.M. (2015) Transport rates of a glutamate transporter homologue are influenced by the lipid bilayer. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9780–9788 10.1074/jbc.M114.630590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rimon A., Mondal R., Friedler A. and Padan E. (2019) Cardiolipin is an optimal phospholipid for the assembly, stability, and proper functionality of the dimeric form of NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 10.1038/s41598-019-54198-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fairman W.A., Sonders M.S., Murdoch G.H. and Amara S.G. (1998) Arachidonic acid elicits a substrategated proton current associated with the glutamate transporter EAAT4. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 105–113 10.1038/355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butchbach M.E.R., Tian G., Guo H. and Lin C.L.G. (2004) Association of excitatory amino acid transporters, especially EAAT2, with cholesterol-rich lipid raft microdomains: Importance for excitatory amino acid transporter localization and function. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34388–34396 10.1074/jbc.M403938200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kalienkova V., Mosina V.C., Bryner L., Oostergetel G.T., Dutzler R. and Paulino C. (2019) Stepwise activation mechanism of the scramblase nhtmem16 revealed by cryo- em. eLife 8, 1–27 10.7554/eLife.44364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Akyuz N., Georgieva E.R., Zhou Z., Stolzenberg S., Cuendet M.A., Khelashvili G. et al. (2015) Transport domain unlocking sets the uptake rate of an aspartate transporter. Nature 518, 68–73 10.1038/nature14158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ewers D., Becher T., Machtens J.P., Weyand I. and Fahlke C. (2013) Induced fit substrate binding to an archeal glutamate transporter homologue. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 12486–12491 10.1073/pnas.1300772110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Z., Tao Z., Gameiro A., Barcelona S., Braams S., Rauen T. et al. (2007) Transport direction determines the kinetics of substrate transport by the glutamate transporter EAAC1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18025–18030 10.1073/pnas.0704570104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hänelt I., Jensen S., Wunnicke D. and Slotboom D.J. (2015) Low affinity and slow Na+ binding precedes high affinity aspartate binding in the secondary-active transporter gltPh. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 15962–15972 10.1074/jbc.M115.656876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oh S. and Boudker O. (2018) Kinetic mechanism of coupled binding in sodium-aspartate symporter GltPh. Elife 7, 1–20 10.7554/eLife.37291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ravera S., Quick M., Nicola J.P., Carrasco N. and Mario Amzel L. (2015) Beyond non-integer Hill coefficients: a novel approach to analyzing binding data, applied to Na+-driven transporters. J Gen Physiol 145, 555–563 10.1085/jgp.201511365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lolkema J.S. and Slotboom D.J. (2019) Models to determine the kinetic mechanisms of ioncoupled transporters. J. Gen. Physiol. 151, 369–380 10.1085/jgp.201812055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burtscher V., Schicker K., Freissmuth M. and Sandtner W. (2019) Kinetic models of secondary active transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, E5365 10.3390/ijms20215365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jensen S., Guskov A., Rempel S., Hänelt I. and Slotboom D.J. (2013) Crystal structure of a substrate-free aspartate transporter. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 1224–1226 10.1038/nsmb.2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guskov A., Jensen S., Faustino I., Marrink S.J. and Slotboom D.J. (2016) Coupled binding mechanism of three sodium ions and aspartate in the glutamate transporter homologue gltTk. Nat. Commun. 7, 13420 10.1038/ncomms13420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arkhipova V., Trinco G., Ettema T.W., Jensen S., Slotboom D.J. and Guskov A. (2019) Binding and transport of D-aspartate by the glutamate transporter homolog Glt Tk. eLife 8, 1–12 10.7554/eLife.45286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yernool D., Boudker O., Jin Y. and Gouaux E. (2004) Structure of a glutamate transporter homologue from Pyrococcus horikoshii. Nature 431, 811–818 10.1038/nature03018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Boudker O., Ryan R.M., Yernool D., Shimamoto K. and Gouaux E. (2007) Coupling substrate and ion binding to extracellular gate of a sodium-dependent aspartate transporter. Nature 445, 387–393 10.1038/nature05455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reyes N., Oh S. and Boudker O. (2013) Binding thermodynamics of a glutamate transporter homolog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 20, 634–640 10.1038/nsmb.2548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verdon G., Oh S.C., Serio R. and Boudker O. (2014) Coupled ion binding and structural transitions along the transport cycle of glutamate transporters. eLife 2014, 1–23 10.7554/eLife.02283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scopelliti A.J., Font J., Vandenberg R.J., Boudker O. and Ryan R.M. (2018) Structural characterisation reveals insights into substrate recognition by the glutamine transporter ASCT2/SLC1A5. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–12 10.1038/s41467-017-02444-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Verdon G. and Boudker O. (2012) Crystal structure of an asymmetric trimer of a bacterial glutamate transporter homolog. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19, 355–357 10.1038/nsmb.2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson Z.L., Cheong C.G. and Lee S.Y. (2012) Crystal structure of a concentrative nucleoside transporter from Vibrio cholerae at 2.4 Å. Nature 483, 489–493 10.1038/nature10882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Johnson Z.L., Lee J.H., Lee K., Lee M., Kwon D.Y., Hong J. et al. (2014) Structural basis of nucleoside and nucleoside drug selectivity by concentrative nucleoside transporters. eLife 3, 1–19 10.7554/eLife.03604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu N.J., Iwata S., Cameron A.D. and Drew D. (2011) Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of the bile acid sodium symporter ASBT. Nature 478, 408–411 10.1038/nature10450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thurtle-Schmidt B.H. and Stroud R.M. (2016) Structure of Bor1 supports an elevator transport mechanism for SLC4 anion exchangers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 10542–10546 10.1073/pnas.1612603113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coudray N., Seyler S L., Lasala R., Zhang Z., Clark K.M., Dumont M.E. et al. (2017) Structure of the SLC4 transporter Bor1p in an inward-facing conformation. Protein Sci. 26, 130–145 10.1002/pro.3061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alguel Y., Amillis S., Leung J., Lambrinidis G., Capaldi S., Scull N.J. et al. (2016) Structure of eukaryotic purine/H+ symporter UapA suggests a role for homodimerization in transport activity. Nat. Commun. 7, 1–9 10.1038/ncomms11336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geertsma E.R., Chang Y.N., Shaik F.R., Neldner Y., Pardon E., Steyaert J. et al. (2015) Structure of a prokaryotic fumarate transporter reveals the architecture of the SLC26 family. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 803–808 10.1038/nsmb.3091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Su C.C., Bolla J.R., Kumar N., Radhakrishnan A., Long F., Delmar J.A. et al. (2015) Structure and function of Neisseria gonorrhoeae MtrF illuminates a class of antimetabolite efflux pumps. Cell Rep. 11, 61–70 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bolla J.R., Su C.C., Delmar J.A., Radhakrishnan A., Kumar N., Chou T.H. et al. (2015) Crystal structure of the Alcanivorax borkumensis YdaH transporter reveals an unusual topology. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–10 10.1038/ncomms7874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J.W., Kim S., Kim S., Lee H., Lee J.O. and Jin M.S. (2017) Structural insights into the elevator-like mechanism of the sodium/citrate symporter CitS. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 10.1038/s41598-017-02794-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kebbel F., Kurz M., Arheit M., Grütter M.G. and Stahlberg H. (2013) Structure and substrate-induced conformational changes of the secondary citrate/sodium symporter CitS revealed by electron crystallography. Structure 21, 1243–1250 10.1016/j.str.2013.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mancusso R., Gregorio G.G., Liu Q. and Wang D.N. (2012) Structure and mechanism of a bacterial sodium-dependent dicarboxylate transporter. Nature 491, 622–626 10.1038/nature11542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hunte C., Screpanti E., Venturi M., Rimon A., Padan E. and Michel H. (2005) Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature 435, 1197–1202 10.1038/nature03692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee C., Yashiro S., Dotson D.L., Uzdavinys P., Iwata S., Sansom M.S.P. et al. (2014) Crystal structure of the sodium-proton antiporter NhaA dimer and new mechanistic insights. J. Gen. Physiol. 144, 529–544 10.1085/jgp.201411219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Appel M., Hizlan D., Vinothkumar K.R., Ziegler C. and Kühlbrandt W. (2009) Conformations of NhaA, the Na/H exchanger from Escherichia coli, in the pH-activated and ion-translocating states. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 351–365 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lee C., Kang H.J., Von Ballmoos C., Newstead S., Uzdavinys P., Dotson D.L. et al. (2013) A two-domain elevator mechanism for sodium/proton antiport. Nature 501, 573–577 10.1038/nature12484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Paulino C., Wöhlert D., Kapotova E., Yildiz Ö. and Kühlbrandt W. (2014) Structure and transport mechanism of the sodium/proton antiporter MjNhaP1. eLife 3, 1–21 10.7554/eLife.03583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wöhlert D., Kühlbrandt W. and Yildiz O. (2014) Structure and substrate ion binding in the sodium/proton antiporter PaNhaP. eLife 3, e03579 10.7554/eLife.03579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Luo P., Yu X., Wang W., Fan S., Li X. and Wang J. (2015) Crystal structure of a phosphorylation-coupled vitamin C transporter. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 238–241 10.1038/nsmb.2975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Luo P., Dai S., Zeng J., Duan J., Shi H. and Wang J. (2018) Inward-facing conformation of l-ascorbate transporter suggests an elevator mechanism. Cell Discov. 4, 1–9 10.1038/s41421-018-0037-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yu Y., Zhou M., Kirsch F., Xu C., Zhang L., Wang Y. et al. (2014) Planar substrate-binding site dictates the specificity of ECF-type nickel/cobalt transporters. Cell Res. 24, 267–277 10.1038/cr.2013.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bao Z., Qi X., Hong S., Xu K., He F., Zhang M. et al. (2017) Structure and mechanism of a group-I cobalt energy coupling factor transporter. Cell Res. 27, 675–687 10.1038/cr.2017.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang P., Wang J. and Shi Y. (2010) Structure and mechanism of the S component of a bacterial ECF transporter. Nature 468, 717–720 10.1038/nature09488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Erkens G.B., Berntsson R.P.A., Fulyani F., Majsnerowska M., Vujiĉić-Žagar A., Ter Beek J. et al. (2011) The structural basis of modularity in ECF-type ABC transporters. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 755–760 10.1038/nsmb.2073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Berntsson R.P.A., Ter Beek J., Majsnerowska M., Duurkens R.H., Puri P., Poolman B. et al. (2012) Structural divergence of paralogous S components from ECF-type ABC transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 13990–13995 10.1073/pnas.1203219109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Karpowich N.K., Song J. and Wang D.N. (2016) An aromatic Cap seals the substrate binding site in an ECF-type S subunit for riboflavin. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 3118–3130 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Swier L.J.Y.M., Monjas L., Guskov A., De Voogd A.R., Erkens G.B., Slotboom D.J. et al. (2015) Structure-based design of potent small-molecule binders to the S-component of the ECF transporter for thiamine. ChemBioChem 16, 819–826 10.1002/cbic.201402673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao Q., Wang C., Wang C., Guo H., Bao Z., Zhang M. et al. (2015) Structures of FolT in substrate-bound and substrate-released conformations reveal a gating mechanism for ECF transporters. Nat. Commun. 6, 1–7 10.1038/ncomms8661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rempel S., Colucci E., de Gier J.W., Guskov A. and Slotboom D.J. (2018) Cysteine-mediated decyanation of vitamin B12 by the predicted membrane transporter BtuM. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–8 10.1038/s41467-018-05441-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Santos J.A., Rempel S., Mous S.T.M., Pereira C.T., Ter B.J., de Gier J.W. et al. (2018) Functional and structural characterization of an ECF-type ABC transporter for vitamin B12. eLife 7, 1–16 10.7554/eLife.35828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang M., Bao Z., Zhao Q., Guo H., Xu K., Wang C. et al. (2014) Structure of a pantothenate transporter and implications for ECF module sharing and energy coupling of group II ECF transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 18560–18565 10.1073/pnas.1412246112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Xu K., Zhang M., Zhao Q., Yu F., Guo H., Wang C. et al. (2013) Crystal structure of a folate energy-coupling factor transporter from lactobacillus brevis. Nature 497, 268–271 10.1038/nature12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang T., Fu G., Pan X., Wu J., Gong X., Wang J. et al. (2013) Structure of a bacterial energy-coupling factor transporter. Nature 497, 272–276 10.1038/nature12045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]