Abstract

Several Nocardia strains associated with nocardiosis, a potentially life-threatening disease, house a nonamodular assembly line polyketide synthase (PKS) that presumably synthesizes an unknown polyketide. Here, we report the discovery and structure elucidation of the NOCAP (nocardiosis-associated polyketide) aglycone by first fully reconstituting the NOCAP synthase in vitro from purified protein components followed by heterologous expression in E. coli and spectroscopic analysis of the purified products. The NOCAP aglycone has an unprecedented structure comprised of a substituted resorcylaldehyde headgroup linked to a 15-carbon tail that harbors two conjugated all-trans trienes separated by a stereogenic hydroxyl group. This report is the first example of reconstituting a trans-acyltransferase assembly line PKS in vitro and of using these approaches to “deorphanize” a complete assembly line PKS identified via genomic sequencing. With the NOCAP aglycone in hand, the stage is set for understanding how this PKS and associated tailoring enzymes confer an advantage to their native hosts during human Nocardia infections.

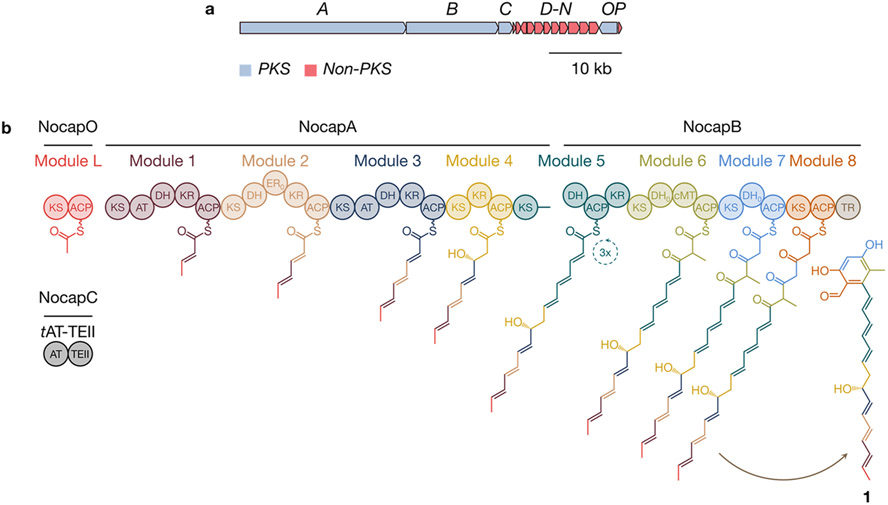

Within the past decade, genomic sequencing has exposed many “orphan” biosynthetic gene clusters encoding assembly line PKSs whose products have yet to be identified.1 Analysis of orphan polyketide synthases (PKSs) has the potential to reveal new biosynthetic strategies as well as products with unprecedented structures and biological activities. Of particular interest to our laboratory is an intriguing family of orphan assembly line PKSs termed nocardiosis-associated polyketide (NOCAP) synthases. NOCAP synthases harbor cis- and trans-acyltransferases2 and are only found in strains of the actinomycete Nocardia, most of which are isolated from patients affected with nocardiosis, a serious pulmonary or systemic disease3-5 (Table S1). The NOCAP synthase is clustered with sugar biosynthesis and transfer enzymes and is composed of four separate proteins containing nine PKS modules (eight of which are collinear) (Figure 1, Table S2). Modules 1 and 3 possess their own acyltransferase domains, whereas the remaining modules require a trans-acyltransferase (tAT) to supply malonyl extender units. Notably, this PKS has three other infrequent features: (a) a naturally split (junction between KS/DH domains) and “stuttering” module capable of catalyzing three elongation and reductive cycles (module 5),5,8,9 (b) a terminal thioester reductase (TR),10 and (c) a thioesterase (TE) domain fused to the tAT. In a preliminary study, several unprecedented, albeit partially characterized, octaketide and heptaketide products were generated by incubating purified modules 4–8 with surrogate primer unit octanoyl-CoA.5 Building on our laboratory’s prior experience in functionally reconstituting the complete 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS) in E. coli6 and from purified protein components,7 we sought to deorphanize a prototypical NOCAP synthase outside of its genetically difficult and potentially hazardous natural host using both of these approaches. Here we report on the successful reconstitution of the entire assembly line NOCAP synthase in vitro as well as in E. coli.

Figure 1.

(a) Prototypical NOCAP synthase biosynthetic gene cluster from N. puris. (b) Biosynthesis of 1 by the NOCAP synthase. Key: KS, ketosynthase; AT, acyltransferase; DH, dehydratase; KR, ketoreductase; ER, enoylreductase; cMT, C-methyltransferase; ACP, acyl carrier protein; TR, thioester reductase; and TEII, thioesterase II.

We hypothesized that the uncharacterized module L (previously named “X”) synthesizes a primer unit for the collinear assembly line comprised of modules 1–8. Accordingly, we expressed a soluble maltose-binding protein (MBP)-module L fusion protein in E. coli and purified it to homogeneity (Figure S1). To identify substrates and products bound to its acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain by intact protein LC-MS, we further expressed and purified two derivatives of this protein: MBP-module L without the ACP domain (KSL) and stand-alone ACPL (Figure S2). Apo-ACPL was incubated with Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase11 and malonyl-CoA to obtain malonyl-S-ACPL, which was then incubated with KSL. LC-MS analysis revealed that malonyl-S-ACPL was predominantly decarboxylated to acetyl-S-ACPL in a KSL-dependent manner (Figure 2a), suggesting that KSL is able to decarboxylate malonyl-S-ACPL to generate an acetyl unit for translocation to module 1. Interestingly, while KSL appears functionally analogous to specialized KSQ domains,12 its active site Cys residue is not replaced by a highly conserved Gln.

Figure 2.

In vitro characterization of modules L, 1, and 2 and tAT-TEII. (a) Extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of 11+ charge state for malonyl-S-ACPL and acetyl-S-ACPL in the presence or absence of: KSL. (b) EICs of malonyl-PPant and sorbyl-PPant ejected from malonyl-S-ACP2 and sorbyl-S-ACP2, respectively, in the presence or absence of module L. (c) EICs of 11+ charge states for acetyl-S-ACP1 and holo-ACP1 in the presence or absence of either tAT or tAT-TEII

To assay the overall activity of modules L, 1, and 2, a bimodular protein (KS1-AT1-DH1-KR1-ACP1-KS2-DH2-ER2-KR2) lacking ACP2 was expressed and purified; separately, stand-alone holo-ACP2 was also expressed and purified. These proteins were assayed via a phosphopantetheine (PPant) ejection assay13 in the presence of MBP–module L, truncated tAT (i.e., lacking its TE domain; see below paragraph), and appropriate substrates. In this and all subsequent assays utilizing malonyl-CoA, this labile substrate was generated in situ by adding malonic acid, CoASH, ATP, and Streptomyces coelicolor malonyl-CoA synthetase MatB14 to the reaction mixture. Instead of detecting the anticipated hex-4-enoyl-PPant species, sorbyl-PPant was the major observed product (Figure 2b), implying that the enoylreductase (ER) domain of module 2 is inactive (designated ER0 from here onward). Together, these results confirm our hypothesis that module L–module 1–module 2 comprise the first three modules for initiation of NOCAP biosynthesis.

We hypothesized that the TE domain of the tAT-TE protein hydrolyzes acyl-ACPs under conditions of “stalled” polyketide biosynthesis.15-18 This suggestion was consistent with our earlier observation that absence of the TE did not affect tAT activity, but use of truncated tAT in place of full-length tAT-TE resulted in a 2- to 10-fold decrease in product formation.5 To test this hypothesis, we incubated Sfp-derived acetyl-S-ACP1, a stalled acyl-ACP surrogate, with either tAT-TE or tAT. LC-MS analysis uncovered that acetyl-S-ACP1 was hydrolyzed to holo-ACP1 in the presence of tAT-TE but not tAT (Figure 2c). Analogous radiolabeling experiments further verified the above findings (Figure S3). Together, these results provide strong evidence that this TE is a member of the “TEII” subfamily of thioesterases (designated TEII hereafter) that acts as a proofreading enzyme by hydrolyzing unproductive intermediates.

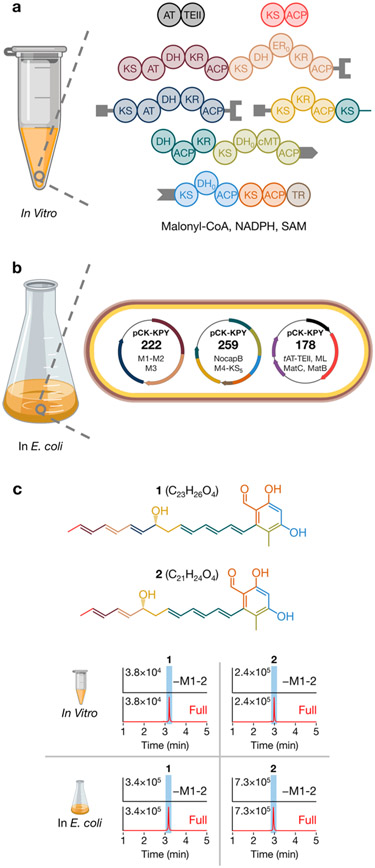

Buoyed by the reconstitution of modules L, 1, and 2, we endeavored to reconstitute in vitro the complete NOCAP synthase. To overcome its exceptionally large size (the synthase’s homodimeric mass approaches 3 MDa), multi-modular proteins were dissected into smaller unimodular or bimodular proteins that could easily be expressed in E. coli.7 To facilitate intermodular chain translocation between separated modules, each protein was fused to complementary N-terminal and/or C-terminal docking domains from DEBS that have previously been shown to facilitate noncovalent interactions between successive modules on a PKS assembly line.19-21 NocapA was expressed and purified as three stand-alone proteins: modules 1 and 2 as one bimodular protein, module 3 as a unimodular protein, and module 4 along with the KS domain of module 5 (module 4-KS5) as the third protein. Separately, NocapB was dissociated into two proteins: DH-ACP-KR tridomain of module 5 fused to complete module 6 (DH5-ACP5-KR5-module 6) and a bimodular protein composed of modules 7 and 8 along with the terminal TR domain (modules 7-8-TR) (Figures 3a, S1). These five NOCAP synthase-derived proteins were mixed with MBP-module L, tAT-TEII, malonyl-CoA, NADPH, and S-adenosyl methionine. To confirm that products originated from the assembly line PKS, [2-13C]-, [1,3-13C2]-, or [13C3]-malonyl-CoA was used in place of malonyl-CoA in parallel reactions.

Figure 3.

Reconstitution of the NOCAP synthase (a) in vitro and (b) in E. coli. (c) EICs of 1 and 2 from either in vitro reactions or E. coli pellet extracts. As a negative control, modules 1 and 2 (as one bimodular protein) were omitted.

By high-resolution MS, we identified polyketide 1 with a molecular formula of C23H26O4 (observed [M – H]− m/z 365.1762, theoretical [M – H]− m/z 365.1753, 2.5 ppm) (Figure 3c). The observation of +11, +11, and +22 mass shifts for 1 in mixtures containing [2-13C], [1,3-13C2], and [13C3] malonyl-CoA, respectively, indicated that 1 traversed the entire polyketide synthase and underwent three rounds of chain elongation, ketoreduction, and dehydration at module 5 (Figures 1, S4, and S5). Because biosynthesis of 1 requires the entire assembly line PKS, we propose that 1 is the aglycone product of the NOCAP synthase. A closely related polyketide 2 was detected that had presumably undergone one fewer round of chain elongation, ketoreduction, and dehydration than 1 (molecular formula C21H24O4, observed [M – H]− m/z 339.1604, theoretical [M – H]− m/z 339.1596, 2.4 ppm) (Figures S6-S8). Its MS/MS fragmentation pattern matched well with that of 1, leading us to hypothesize that an upstream module was “skipped” during biosynthesis of 2. Two more minor polyketides, 3 and 4, were identified with MS/MS fragmentation patterns noticeably different than 1 and 2 (Figures S9-S14). We hypothesize that 3 and 4 are premature polyketides with a pyrone moiety that originated from spontaneous release after module 7 extension and C-1–C-5 oxygen lactonization.

For definitive structural analysis, we sought to produce the NOCAP synthase products by using E. coli as a heterologous host for scalable polyketide biosynthesis.6 Informed by the in vitro reconstitution experiments summarized above, we engineered three plasmids with compatible antibiotic resistance markers and origins of replication that collectively encode the pathway. To exclude the possibility that matched docking domains facilitate chain translocation between modules 2 and 4, dissociated NocapA proteins were fused with orthogonal docking domains and NocapB was left intact. Plasmid pCK-KPY222 encoded modules 1 and 2 as one bimodular protein and module 3. Plasmid pCK-KPY259 encoded module 4-KS5 and intact NocapB, and pCK-KPY178 encoded tAT-TEII and MBP-module L (Figures 3b, 3). To enhance the malonyl-CoA pool in E. coli, pCK-KPY178 also encodes MatB and Rhizobium leguminosarum malonate carrier protein MatC.22,23 Gratifyingly, E. coli BAP1[pCK-KPY222/pCK-KPY259/pCK-KPY178] produced 1 and 2 (Figures 3c, S15). E. coli-derived 1 and 2 had the same MS/MS fragments as 1 and 2 produced in vitro. Derivatization of 1 and 2 with Girard’s reagent T24 confirmed the presence of an aldehyde (Figures S22-S25). 3 and 4 were much lower in abundance from extracts of this strain, suggesting that these metabolites do not arise under physiological conditions, but are only synthesized under conditions with excess substrates. Because of their scarcity in E. coli, 3 and 4 were not further characterized.

We isolated 1 and 2 as faint yellow solids from 4 L of E. coli BAP1[pCK-KPY222/pCK-KPY259/pCK-KPY178] using lipid extraction with methyl tert-butyl ether/methanol,25 C18 solid-phase extraction, and UV-absorbance-guided semipreparative HPLC, with yields on the order of 1–10 mg/L (Figures S26-S28). A number of 1D and 2D NMR experiments (1H, COSY, TOCSY, HSQC, HMBC, NOESY, and ROESY) allowed us to fully elucidate their chemical structures (Figures 4, S29-S60; Table S3).

Figure 4.

Structures of 1 and 2 assembled from 2D NMR data.

For 1, COSY, TOCSY, and HMBC experiments established carbon–carbon connectivity from C-1 (195.1 ppm) to C-22 (18.3 ppm) as well as the phenolic moiety resulting from C-2–C-7 aldol condensation. These spectra also revealed a pair of conjugated trienes, one synthesized by modules 1–3 and the other by module 5. The aldehyde substituent at C-1 shows that 1 and 2 were released from the assembly line by the terminal TR domain. We observed expected hydroxyl substituents at C-3 (163.6 ppm, module 8), C-5 (160.8 ppm, module 7), and C-15 (71.9 ppm, module 4), a singlet methyl substituent at C-6 (114.7 ppm, module 6), and a terminal doublet methyl (C-22 for 1, C-20 for 2, module L). ROESY analysis of 1 and NOESY analysis of 2 verified that all of their double bonds have trans stereoconfigurations as predicted by bioinformatic analysis.26 To determine the absolute configuration of the stereocenter set by module 4’s KR domain, we converted the C-15 hydroxyl substituent of 2 to a Mosher ester.27 Mosher ester analysis with COSY confirmed that the absolute configuration at C-15 is R, also as predicted by bioinformatic analysis26 (Figures S61-S64). Unlike 1, compound 2 featured a conjugated diene—not triene—in its “tail”. We therefore hypothesized that a combination of the dissociated-by-design nature of module 3 and broad substrate tolerance of the KS domain of module 45 permitted facile chain translocation of a growing polyketide chain from module 2 to module 4 despite mismatched docking domains. Indeed, E. coli that does not express module 3 only produced 2, substantiating our hypothesis that biosynthesis of 2 involves bypassing module 3 (Figure S65). Collectively, these spectroscopic efforts validated 1 as the aglycone product of the NOCAP synthase.

This report represents two milestones. First, we describe for the first time the full in vitro reconstitution of an assembly line PKS that is predominantly comprised of trans-AT modules. trans-AT PKSs represent over 23% of all sequenced assembly line PKSs according to a recent survey28 and display remarkable architectural diversity; however, the understanding of trans-AT PKSs has significantly lagged that of cis-AT PKSs2. Based on this report, the NOCAP synthase is a promising model for analyzing the structure–function relationships of trans-AT PKSs. Second, this work concludes the first example of polyketide discovery by reconstituting orphan assembly line PKSs in vitro. In principle, the methodology described here could be applied to other orphan polyketides, especially those synthesized in low abundance or from unculturable organisms.29 The discovery and structure elucidation of 1 will also allow us to turn our attention to substantiating its presence in Nocardia and the ultimate characterization of the biological role of its fully decorated natural product. Such efforts are compellingly motivated by the statistically significant but nonetheless correlative occurrence of this PKS in strains associated with clinical cases of nocardiosis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank past and present members of the C.K. laboratory for fruitful discussions and suggestions. We also thank Theresa McLaughlin (Stanford University) and Jeffrey G. Pelton (University of California, Berkeley) for technical assistance, and Prof. Joseph D. Puglisi for access to his 500 MHz NMR spectrometer. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01 GM087934 (to C.K.) and NIH Grant F32 GM123637 (to K.P.Y.). This work utilized the Stanford Cancer Institute Proteomics/Mass Spectrometry Shared Resource, which is supported by NIH Grant P30 CA124435, and the 900 MHz NMR spectrometer (funded by NIH Grant P41 GM068933) at the Central California 900 MHz NMR Facility.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.0c00904

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c00904.

Detailed methods, figures, and tables (PDF)

Contributor Information

Kai P. Yuet, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Corey W. Liu, Department of Structural Biology and Stanford ChEM-H, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

Stephen R. Lynch, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

James Kuo, Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

Wesley Michaels, Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

Robert B. Lee, Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Abigail E. McShane, Department of Bioengineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Brian L. Zhong, Department of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Curt R. Fischer, Stanford ChEM-H, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States

Chaitan Khosla, Department of Chemistry, Department of Chemical Engineering, and Stanford ChEM-H, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).O’Brien RV; Davis RW; Khosla C; Hillenmeyer ME Computational identification and analysis of orphan assembly-line polyketide synthases. J. Antibiot 2014, 67, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Helfrich EJN; Piel J Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep 2016, 33, 231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Kageyama A; Yazawa K; Mukai A; Kohara T; Nishimura K; Kroppenstedt RM; Mikami Y Nocardia araoensis sp. nov. and Nocardia pneumoniae sp. nov., isolated from patients in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2004, 54, 2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wilson JW Nocardiosis: updates and clinical overview. Mayo Clin. Proc 2012, 87, 403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Kuo J; Lynch SR; Liu CW; Xiao X; Khosla C Partial in vitro reconstitution of an orphan polyketide synthase associated with clinical cases of nocardiosis. ACS Chem. Biol 2016, 11, 2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pfeifer BA; Admiraal SJ; Gramajo H; Cane DE; Khosla C Biosynthesis of complex polyketides in a metabolically engineered strain of E. coli. Science 2001, 291, 1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Lowry B; Robbins T; Weng CH; O’Brien RV; Cane DE; Khosla C In vitro reconstitution and analysis of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 16809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Olano C; Wilkinson B; Sanchez C; Moss SJ; Sheridan R; Math V; Weston AJ; Brana AF; Martin CJ; Oliynyk M; Mendez C; Leadlay PF; Salas JA Biosynthesis of the angiogenesis inhibitor borrelidin by Streptomyces parvulus Tü4055: cluster analysis and assignment of functions. Chem. Biol 2004, 11, 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Weber T; Laiple KJ; Pross EK; Textor A; Grond S; Welzel K; Pelzer S; Vente A; Wohlleben W Molecular analysis of the kirromycin biosynthetic gene cluster revealed beta-alanine as precursor of the pyridone moiety. Chem. Biol 2008, 15, 175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gomez-Escribano JP; Song LJ; Fox DJ; Yeo V; Bibb MJ; Challis GL Structure and biosynthesis of the unusual polyketide alkaloid coelimycin P1, a metabolic product of the cpk gene cluster of Streptomyces coelicolor M145. Chem. Sci 2012, 3, 2716. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Quadri LE; Weinreb PH; Lei M; Nakano MM; Zuber P; Walsh CT Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Bisang C; Long PF; Cortés J; Westcott J; Crosby J; Matharu AL; Cox RJ; Simpson TJ; Staunton J; Leadlay PF A chain initiation factor common to both modular and aromatic polyketide synthases. Nature 1999, 401, 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dorrestein PC; Bumpus SB; Calderone CT; Garneau-Tsodikova S; Aron ZD; Straight PD; Kolter R; Walsh CT; Kelleher NL Facile detection of acyl and peptidyl intermediates on thiotemplate carrier domains via phosphopantetheinyl elimination reactions during tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hughes AJ; Keatinge-Clay A Enzymatic extender unit generation for in vitro polyketide synthase reactions: structural and functional showcasing of Streptomyces coelicolor MatB. Chem. Biol 2011, 18, 165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hu Z; Pfeifer BA; Chao E; Murli S; Kealey J; Carney JR; Ashley G; Khosla C; Hutchinson CR A specific role of the Saccharopolyspora erythraea thioesterase II gene in the function of modular polyketide synthases. Microbiology 2003, 149, 2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kim BS; Cropp TA; Beck BJ; Sherman DH; Reynolds KA Biochemical evidence for an editing role of thioesterase II in the biosynthesis of the polyketide pikromycin. J. Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 48028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kotowska M; Pawlik K Roles of type II thioesterases and their application for secondary metabolite yield improvement. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 2014, 98, 7735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Heathcote ML; Staunton J; Leadlay PF Role of type II thioesterases: evidence for removal of short acyl chains produced by aberrant decarboxylation of chain extender units. Chem. Biol 2001, 8, 207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wu N; Cane DE; Khosla C Quantitative analysis of the relative contributions of donor acyl carrier proteins, acceptor ketosynthases, and linker regions to intermodular transfer of intermediates in hybrid polyketide synthases. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 5056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Klaus M; Ostrowski MP; Austerjost J; Robbins T; Lowry B; Cane DE; Khosla C Protein-protein interactions, not substrate recognition, dominate the turnover of chimeric assembly line polyketide synthases. J. Biol. Chem 2016, 291, 16404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Broadhurst RW; Nietlispach D; Wheatcroft MP; Leadlay PF; Weissman KJ The structure of docking domains in modular polyketide synthases. Chem. Biol 2003, 10, 723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Lombó F; Pfeifer B; Leaf T; Ou S; Kim YS; Cane DE; Licari P; Khosla C Enhancing the atom economy of polyketide biosynthetic processes through metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Prog 2001, 17, 612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Leonard E; Yan Y; Fowler ZL; Li Z; Lim CG; Lim KH; Koffas MA Strain improvement of recombinant Escherichia coli for efficient production of plant flavonoids. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2008, 5, 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Girard A; Sandulesco G Sur une nouvelle série de réactifs du groupe carbonyle, leur utilisation à l’extraction des substances cétoniques et à la caractérisation microchimique des aldéhydes et cétones. Helv. Chim. Acta 1936, 19, 1095. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Matyash V; Liebisch G; Kurzchalia TV; Shevchenko A; Schwudke D Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J. Lipid Res 2008, 49, 1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Caffrey P Conserved amino acid residues correlating with ketoreductase stereospecificity in modular polyketide synthases. ChemBioChem 2003, 4, 654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hoye TR; Jeffrey CS; Shao F Mosher ester analysis for the determination of absolute configuration of stereogenic (chiral) carbinol carbons. Nat. Protoc 2007, 2, 2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Nivina A; Yuet KP; Hsu J; Khosla C Evolution and diversity of assembly-line polyketide synthases. Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rutledge PJ; Challis GL Discovery of microbial natural products by activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 2015, 13, 509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.