Abstract

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are often overexpressed or mutated in cancers and drive tumor growth and metastasis. In the current model of RTK signaling, including that of the RTK MET, downstream phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) mediates both cell proliferation and cell migration, whereas the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) Rac1 mediates cell migration. Here, however, in cultured NIH3T3 and glioblastoma cells, we found that class I PI3K mediated oncogenic MET-induced cell migration but, unexpectedly, not anchorage-independent growth. In contrast, Rac1 regulated both in distinct ways: Downstream of PI3K, Rac1 mediated cell migration through its GTPase activity; whereas, independently of PI3K, Rac1 mediated anchorage-independent growth in a GTPase-independent manner through an adaptor function. Through its RKR motif, Rac1 formed a complex with the kinase mTOR to promote its translocation to the plasma membrane, where its activity promoted anchorage-independent growth of the cell cultures. Inhibiting mTOR with rapamycin suppressed the growth of subcutaneous MET-mutant cell grafts in mice, including that of MET inhibitor-resistant cells. These findings reveal a GTPase-independent role for Rac1 in mediating a PI3K-independent MET-to-mTOR pathway and suggest alternative or combined strategies that might overcome resistance to RTK inhibitors in cancer patients.

Introduction

Metastasis is the major cause of death in cancer patients. During this process, cancer cells detach from the primary tumour, acquire the property to overcome anoikis (apoptosis induced by the cell’s detachment from the extracellular matrix), migrate, and at least transiently survive and proliferate in anchorage-independent conditions, enabling them to colonize a new niche (1). Metastatic disease is notoriously challenging to treat and there is currently no cure. Thus, identifying the pathways that promote cell migration and anchorage-independent growth would facilitate the development of novel therapeutic strategies.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) mediate various normal cellular functions as well as stimulate tumor growth and metastasis (2, 3); oncogenic forms of RTKs promote anchorage-independent proliferation (hereafter, growth) and migration (2, 4). The RTK c-MET (or, herein, MET) is activated by the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and is frequently overexpressed or mutated in cancers, and the extent of its overexpression correlates with poor prognosis in patients (2, 5). MET inhibitors are being evaluated in the clinic; however, experience with other RTK inhibitors suggest that the chances of drug resistance developing are high (6). Therefore, alternative or complementary therapies—such as those targeting signaling pathways downstream of RTK activation—may be required to efficiently target MET- and, more generally, oncogenic RTK-driven cancers (7–9).

Activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT signaling pathway has been described as critical for migration (10) and anchorage-independent growth (1, 11). Mammals have eight PI3K catalytic subunits, divided into 3 classes: I, II, and III. The class I PI3K isoforms are often overexpressed or mutated in cancer and can have oncogenic activity (12–16). Amongst the PI3K isoforms, the class IA sub-type of PI3Ks has been linked to RTK signalling. The class IA catalytic subunits (p110α, β or δ) occur in complex with a regulatory subunit of the p85 family. Whereas p110α and p110β are widely expressed, p110δ is mainly found in leukocytes (17, 18). As a major signal transducer of RTKs (2, 19, 20), including MET (21), PI3K promotes cell survival and (as we understand it currently) cell migration. Therefore, the investigation of the roles of the different PI3K isoforms is a highly active area of research and drug development.

PI3K signaling crosstalks with members of the Rho-guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) family, which include RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42. They are active when bound to GTP and in active when bound to GDP. Switching between these states is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs)—which mediate the exchange of bound GDP for GTP, essentially activating the GTPase—and GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs)—which induce the GTPase to hydrolize the GTP into GDP, essentially switching it off—as well as guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) (23). Rac1 has been widely described as a key regulator in promoting actin reorganization, changes in cell shape, and cell migration (24) downstream of various receptors, including RTKs (4, 25–28).

We have previously reported that the oncogenic, constitutively active MET mutants M1268T and D1246N (METM1268T and METD1246N), originally identified in human papillary renal carcinomas (29), signal on endosomes to promote both cell migration and anchorage-independent growth (4). The activation of the Rho-GTPase Rac1 on endosomes was shown to mediate cell migration stimulated by mutant MET (4) and also by ligand (HGF)-activated wild-type MET (26, 27). Here, using isogenic wild-type and mutant MET-expressing mouse fibroblast NIH3T3 cell lines, as well as a glioblastoma cell line that reportedly exhibits autocrine loop-induced oncogenic MET activity (30), we delineated the PI3K- and Rac1-associated pathways responsible for each of these metastasis-associated behaviors downstream of oncogenic MET.

Results

Class I PI3K inhibition reduces MET-dependent cell migration but not anchorage-independent growth

Cell migration and anchorage-independent growth assays were performed in mouse NIH3T3 cells expressing murine wild-type or M1268T-mutant MET and cultured with the pan-PI3K [and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)] inhibitor LY294002, which was previously shown to reduce MET signaling (21, 31–33). A pharmacological inhibitor of MET, PHA-665752, was also used to modulate the pathway at the receptor level. METM1268T was constitutively phosphorylated, as reported previously (34), and PHA-665752, but not LY294002, reduced its phosphorylation (fig. S1, A and B), whereas levels of wild-type and M1268T-mutant MET were comparable (fig. S1C). Both inhibitors reduced METM1268T-dependent cell migration through Transwell chambers (Fig. 1A) and anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (Fig. 1, B and C, and fig. S1D), with no detectable impact on cells expressing wild-type MET (Fig. 1, A to C, and fig. S1D).

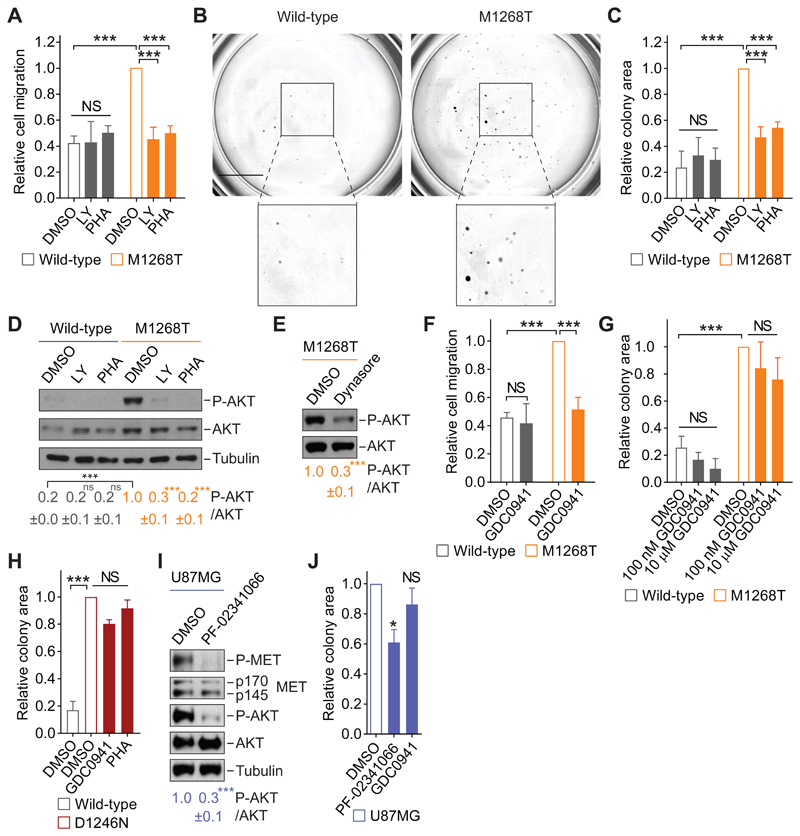

Fig. 1. Class I PI3K inhibition reduces MET-dependent cell migration but not anchorage-independent growth.

(A) Transwell migration assay performed with wild-type or M1268T MET-expressing NIH3T3 cells treated with DMSO, LY294002 (LY, 10 μM) or PHA-665752 (PHA, 100 nM). Data are mean ± SEM from N = 5 (DMSO), 4 (LY), or 3 (PHA) independent biological replicates. Student’s t test: NS, non-significant; ***P<0.005. (B and C) Colony formation assays in the cells described and treated as in (A) and grown in soft agar. Representative images are shown (B; scale bar: 5 mm), and the colony area was calculated by ImageJ (C). Data are mean ± SEM from N=3 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test: NS, non-significant; ***P<0.005. (D and E) Western blotting for phosphorylated (“P-AKT”, Ser473) and total AKT, with tubulin as loading control, in lysates from cells described and treated as in (A) or with dynasore (E; 80 μM). Below, mean densitometry of phosphorylated AKT relative to total ± SEM from N=3 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test (unless indicated, compared to control): NS, non-significant; ***P<0.005. (F and G) As in (A) and (C), respectively, in cells treated with DMSO or GDC0941 (F, 100 nM; G, as indicated). Data are mean ± SEM from at least 3 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test: NS, non-significant; ***P<0.005. (H) Relative colony formation by wild-type or D1246N MET-expressing cells grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO, GDC0941 (100 nM) or PHA-665752 (PHA, 100 nM). Data are mean ± SEM from N=3 independent biological replicates. One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test: NS, non-significant; ***P<0.005. (I) Western blotting for phosphorylated (Tyr1234/1235) and total MET and AKT in lysates from U87MG cells treated with DMSO or PF-02341066 (100 nM). p170 and p145: the precursor and the mature forms of the beta chain of MET. Blots were analyzed as in (D and E). (J) Relative colony area of U87MG cells grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO, PF-02341066 (100 nM) or GDC0941 (100 nM). Data are means ± SEM from at least 3 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test (compared to control): NS, non-significant; *P<0.05.

The kinase AKT, a substrate of PI3K, was notably phosphorylated in the METM1268T-expressing cells compared to the wild-type MET-expressing cells; its activation was lost upon pharmacological inhibition of PI3K/mTOR or of MET (Fig. 1D). Moreover, inhibiting endocytosis with dynasore, a pharmacological inhibitor of the GTPase dynamin and which we previously showed reduces the endocytosis of METM1268T (4), significantly reduced the phosphorylation of AKT in METM1268T-expressing cells (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that the MET mutant activates AKT on intracellular compartments, consistent with our previous description of constitutive endocytosis of METM1268T and its signaling on endosomes (4) as well as with the reported activation of AKT on endosomes (35).

Because the compound LY294002 has multiple targets other than PI3K (36, 37), and AKT is one of the major effectors of class I PI3Ks, the influence of the selective pan-class I PI3K inhibitor GDC0941 (38) was assessed. GDC0941 reportedly inhibits downstream effectors of class I PI3K with half-maximal response (EC50) values ranging from 15 to 709 nM (39). A concentration response analysis established that 100 nM of GDC0941 robustly reduced the phosphorylation of AKT in METM1268T cells (fig. S1E). In the presence of GDC0941, the level of cell migration seen in METM1268T cells was reduced to a level similar to that seen in wild-type cells; whereas the inhibitor had no discernible effect on the wild-type cells (Fig. 1F). In contrast, treatment with 100 nM of GDC0941 did not significantly alter anchorage-independent growth of wild-type, or METM1268T cells. A 100-fold higher concentration (10 μM) also had no significant effect on anchorage-independent growth (Fig. 1G, fig. S1F). Similarly, GDC0941 did not reduce the anchorage-independent growth of METD1246N cells (Fig. 1H, fig. S1G). We saw similar results in U87MG glioblastoma cells. In these cells, MET was phosphorylated (Fig. 1I), as expected and consistent with the previously reported presence of an autocrine loop (30). The phosphorylation of both MET and AKT was significantly decreased in these cells in presence of the pharmacological MET inhibitor PF-02341066 (Fig. 1I), and AKT phosphorylation was reduced in the presence of GDC0941 (fig. S1H). Whereas PF-02341066 signifcantly reduced the anchorage-independent growth of these cells (by ~40%), the effect of GDC0941 was not significant (Fig. 1J and fig. S1I). Although generally class I PI3K has been considered to be a growth promotor (12, 19, 20), these results indicate a role for class I PI3K in cell migration, but not in anchorage-independent growth, downstream of oncogenic MET.

Class I PI3K promotes MET-dependent cell migration through activation of Rac1

To explore the PI3K pathway that mediated cell migration, we inhibited the class I PI3K isoforms p110α and/or p110β in our wild-type and METM1268T cells, in which both p110α and p110β was detected at similar abundances (fig. S2A). We treated cells with isoform-selective inhibitors: A66 to inhibit p110α, and/or TGX221 to inhibit p110β, and assessed cell migration through Transwell chambers. When applied alone, neither compound had an effect; however, their combination significantly reduced the migration of METM1268T cells to the level observed in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). The combination had no effect on wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). These results were reproduced by knocking down p110α and p110β with siRNA . Their combined knockdown (fig. S2B) reduced the migration of METM1268T cells to the same level seen in wild-type cells (Fig. 2A). The knockdown of either isoform did not modify the expression of the other (fig. S2C), and the inhibition of p110α and p110β combined did not interfere with the cell adhesion (fig. S2D). Similarly to results obtained in METM1268T NIH3T3 cells, PF-02341066 (a MET inhibitor) or a combination of A66 and TGX221 (the p110α and p110β inhibitors) significantly reduced cell migration in U87MG cultures; whereas inhibiting either p110α or p110β alone had no significant effect (Fig. 2B). Thus, our pharmacological inhibition and knockdown data show that both class I PI3Ks p110α and p110β mediate oncogenic MET-dependent cell migration.

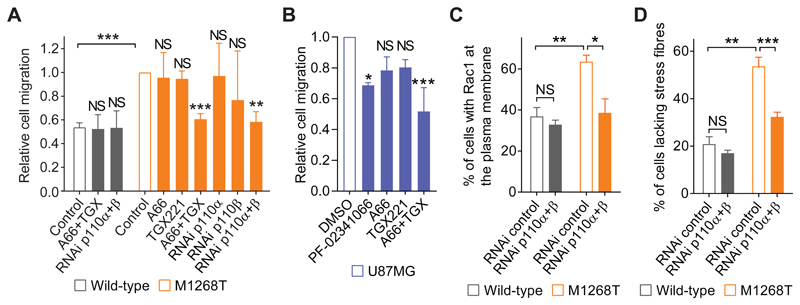

Fig. 2. Class I PI3K promotes MET-dependent cell migration through Rac1 activation.

(A) Transwell migration assays performed with wild-type or M1268T MET-expressing cells transfected with a negative control or siRNA targeting p110α, p110β, or both, and treated with DMSO (control), A66 (500 nM) or TGX221 (TGX, 40 nM) either alone or combined. Data are means ± SEM, N=3 or 4 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test (compared to control, or as indicated): NS, non-significant; **P<0.01, ***P<0.005. (B) Transwell migration by U87MG cells treated with DMSO (N=8), PF-02341066 (100 nM, N=3), A66 (500 nM, N=3), TGX221 (40 nM, N=3) or A66 and TGX221 combined (A66+TGX, N=4). Data are means ± SEM from independent biological replicates. Student’s t test (compared to control, or as indicated): NS, non-significant; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.One-way ANOVA test followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (compared to control): NS, non-significant; *P<0.05, ***P<0.005. (C and D) Wild-type and M1268T MET-expressing cells were transfected with negative control (RNAi control) or p110α and p110β combined (RNAI p110 α+ β) siRNAs. The percentage of cells with Rac1 at the plasma membrane (C) or lacking stress fibres (D) was counted, following immunostaining with an antibody against Rac1 or rhodamine-phalloidin, respectively. Data are means ± SEM from N=3 independent biological replicates. Student’s t test: NS, non-significant; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

We previously reported that METM1268T-dependent Rac1 activation correlates with an increased localization of Rac1 at the plasma membrane (4, 26), resulting in cytoskeleton rearrangements inferred from a reduction in the number of stress fibres (4). The PI3K/mTOR inhibitor LY294002 and the MET inhibitor PHA-665752 reduced both Rac1 localization at the plasma membrane and the number of METM1268T cells that lacked stress fibres, whereas no significant change occurred in wild-type cells (fig. S2, E to H). Similar results were achieved in METM1268T cells by the combined knockdown of p110α and p110β (Fig. 2, C and D). These results are consistent with the reported role of PI3K upstream of Rac1 activation (10). To further confirm that this also occurs downstream of mutant MET, we used a glutathione S-transferase–fused Cdc42-binding domain CRIB (GST-CRIB) pull-down assay to assess Rac1 activation. The combined knockdown of p110α and p110β reduced the amount of GTP-bound Rac1 in METM1268T cells (fig. S2I), suggesting that mutant MET-dependent Rac1 activation and subsequent cytoskeleton remodelling and cell migration are mediated by the class I PI3K isoforms p110α and p110β.

mTORC1 promotes oncogenic MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth

We then turned to investigate the pathway mediating oncogenic MET-regulated anchorage-independent growth, which—asdescribed above—we had found was sensitive to the pan-PI3K/mTOR inhibitor LY294002 but not to selective class I PI3K inhibitors. We first tested the pan-PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (40, 41). In contrast to LY294002, wortmannin had no significant effect on the area and number of colonies in MET-mutant cells (Fig. 3A and fig S3A), despite markedly reducing AKT phosphorylation (fig. S3H). LY294002 (at the concentration used, 10 μM) reportedly also directly inhibits mTOR (37), whereas wortmannin (used at 100 nM) does not (42, 43). Therefore, we investigated whether mTOR is responsible for oncogenic MET-induced anchorage-independent growth using rapamycin, which inhibits mTOR complex1 (mTORC1) (44). Indeed, rapamycin significantly decreased the anchorage-independent growth (as colony area and number) exhibited by both METM1268T and METD1246N cells as well as U87MG cells, with no significant effect detected in wild-type cells (Fig. 3B and fig. S3B).

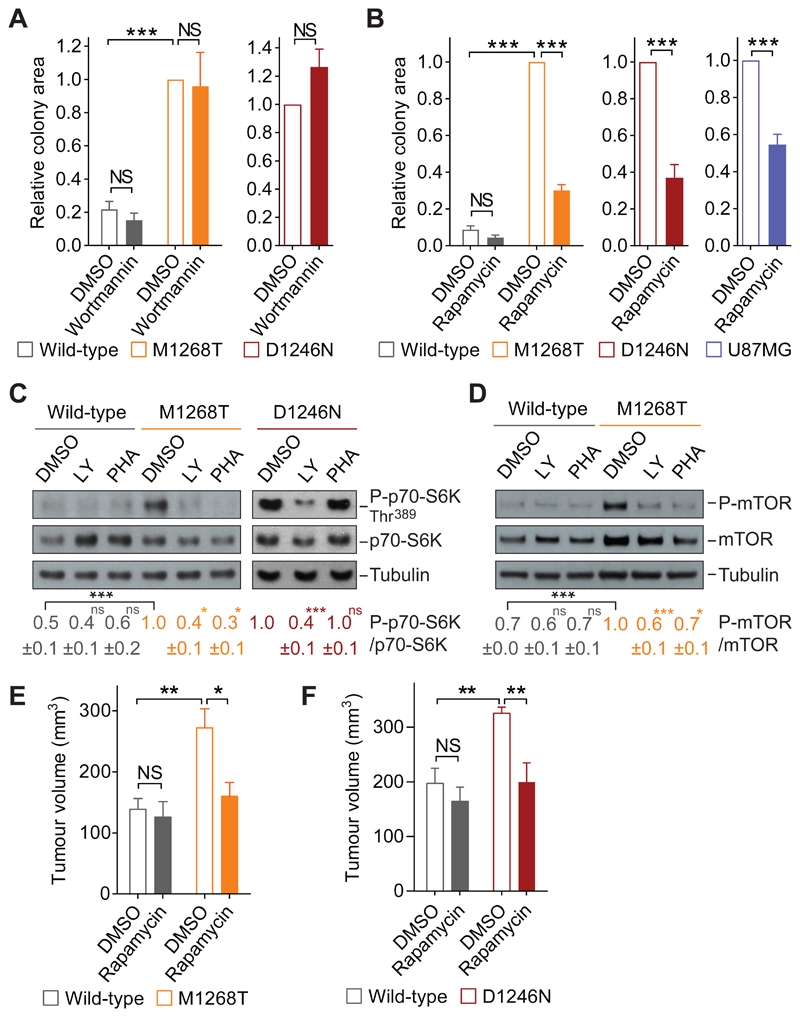

Fig. 3. mTORC1 promotes oncogenic Met-dependent anchorage-independent and tumor growth.

(A) Relative colony area of wild-type, M1268T (N=6 independent biological replicates) and D1246N MET-expressing cells (N=3 independent biological replicates) grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO or wortmannin (100 nM). (B) Relative colony area of wild-type, M1268T and D1246N MET-expressing cells (N=3 independent biological replicates) and U87MG cells (N=4 independent biological replicates) grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO or rapamycin (2 nM). (C and D) Western blots for phosphorylated p70-S6K and mTOR (Ser2481) in lysates from wild-type, M1268T and D1246N MET-expressing cells treated with DMSO, LY294002 (LY, 10 μM) or PHA-665752 (PHA, 100 nM). N= 3 or 4 independent biological replicates. (E and F) Tumour volume of graft of 5x105 cells expressing wild-type, M1268T or D1246N MET injected subcutaneously into nude mice. Tumors were measured daily and, at 30-50 mm3, treated topically with DMSO or rapamycin (2 nM), then assessed at days 4 (E) and 6 (F) thereafter. N=5 mice per group. Data (A to F) are mean values ± SEM. Student’s t test (compared to control or as indicated): NS, non-significant; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

Consistent with these results, the phosphorylation of mTOR (at Ser2481) and of the mTOR effector p70-S6K (at Thr389 and Thr421/Ser424) were higher in METM1268T and METD1246N NIH3T3 cells and U87MG cells than in wild-type MET-expressing NIH3T3 cells (Fig. 3, C and D; and fig. S3, C, D, and F). Thus, we decided to use p70-S6K phosphorylation as a readout of oncogenic MET-dependent mTOR activity and verified that the phosphorylation of p70-S6K and of mTOR was substantially inhibited by the MET inhibitors PHA-665752 in MET-mutant cells (Fig. 3, C and D; and fig. S3, C and D) and PF-02341066 in U87MG cells (fig. S3F).Consistent with a previously published study that METD1246N is resistant to PHA-665752 (4), PHA-665752 did not modify p70-S6K and mTOR phosphorylation in these cells (Fig. 3C, and fig. S3D). We further confirmed that rapamycin significantly reduced p70-S6K phosphorylation in all cells with oncogenic MET (fig. S3, E and F).

PI3K is a upstream regulator of mTOR pathway (45–47). Therefore, all PI3K inhibitors (LY294002, wortmannin, GDC0941, A66+TGX221) expectedly and significantly reduced the phosphorylation of mTOR and p70-S6K (Fig. 3, C and D; and fig. S3, C, D, G, and H). However, because only rapamycin or LY294002 (but not the other PI3K inhibitors) reduced anchorage-independent growth, we concluded that oncogenic MET triggers anchorage-independent growth through an mTORC1 pathway that is stimulated independently from class I PI3K activity. These findings were consistent with a previous study that showed that the mTOR pathway was activated by serum in a PI3K-independent manner (43).

mTORC1 promotes oncogenic MET-induced tumorigenesis

The role of mTORC1 in tumorigenesis driven by METM1268T or METD1246N was further assessed in vivo. In nude mice, METM1268T- or METD1246N-expressing cells rapidly formed subcutaneous tumors, whereas cells expressing wild-type MET formed tumors at a later time (fig. S3I). We have also previously shown that subcutaneous tumors formed by METM1268T-expressing cells are sensitive to topical application of the MET inhibitor PHA-665752 [diluted in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] to the skin above the tumors, whereas tumors formed by wild-type or METD1246N-expressing cells are resistant (4). Rapamycin or the control diluent (DMSO) were similarly applied topically to the skin over tumors that had reached 50 mm3 size (4). The volume of tumors formed by METM1268T- or METD1246N-expressing cells were reduced significantly by rapamycin treatment, whereas no substantial effect was observed on tumors formed by wild-type cells (Fig. 3, E and F). Thus, mTORC1 activity appears to be required for mutant-MET–driven tumorigenesis. Moreover, targeting mTORC1 signaling may represent an alternative strategy to treat patients with MET-driven tumors that are resistant to MET inhibitors.

Oncogenic MET promotes anchorage-independent growth through a Rac1-mTOR pathway

We next aimed to understand how oncogenic MET stimulates the mTORC1 pathway to promote anchorage-independent growth. We previously reported that METM1268T signaling is dependent on endocytosis (4). Indeed, inhibiting endocytosis using the dynamin inhibitor dynasore significantly reduced METM1268T-dependent phosphorylation of p70-S6K (Fig. 4A). This suggested that the constitutive endocytosis of the mutant MET mediates the subsequent activation of mTORC1. HGF-induced activation of MET has been described to lead to the phosphorylation of the mTORC1’ effector p70-S6K through class I PI3K/AKT activity to induce cell survival (48). However, our results described thus far suggest that, in these cells, MET signals to mTORC1 independently from class I PI3K activity in the induction of anchorage-independent growth. mTORC1 can also be regulated by the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway (49), and we have reported that METM1268Tactivates the downstream MAPK-pathway kinase ERK1/2 (50). However, we excluded the involvement of this pathway here because the inhibition of another, upstream MAPK-pathway kinase MEK by the compound U0126 had no significant effect on the phosphorylation of p70-S6K induced by METM1268T expression although it did suppress that of ERK1/2 (Fig. 4B).

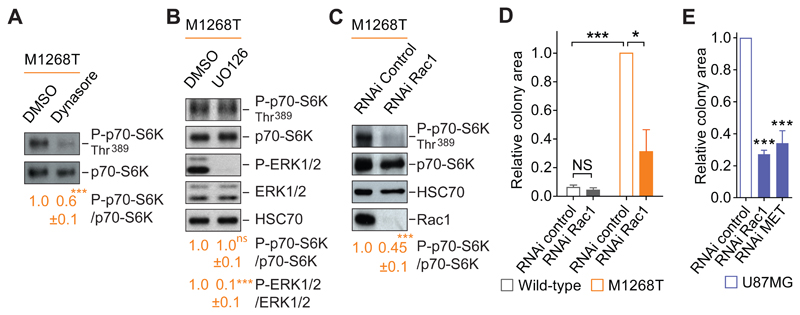

Fig. 4. Oncogenic Met promotes anchorage-independent growth via a Rac1-mTOR pathway.

(A and B) Western blots for phosphorylated p70-S6K (P-p70-S6K), p70-S6K (A and B), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2), ERK1/2 and HSC70 (B) were performed on M1268T MET-expressing cells treated with DMSO, dynasore (80 μM) or UO126 (10 μM), as indicated. Data below blots are mean ± SEM, phospho:total ratio, obtained by densitometry of N=3 independent biological replicates. (C) Western blots for phosphorylated p70-S6K (P-p70-S6K), p70-S6K, HSC70 and Rac1 were performed on M1268T MET-expressing cells transfected with negative control or Rac1 siRNA (“RNAi”). Below are mean levels of indicated phosphorylated protein over total protein ± SEM, obtained by densitometry of Western blots. N=3 independent biological replicates. (D and E) Relative colony area of (D) wild-type and M1268T MET-expressing cells and (E) U87MG cells transfected with negative control or Rac1 RNAi and grown in soft agar. N=3 independent biological replicates. Data (A to E) are mean values ± SEM. P values were obtained with the Student’s t test. NS: non-significant, *P<0.05, ***P<0.005.

Rac1 and Rho-GTPases family proteins mostly are known to have a role in cytoskeleton dynamics and cell motility; however, roles for Rho-GTPases and the Rho-associated kinase ROCK1/2 in cell growth, cell cycling and tumorigenesis have been reported (23, 43, 51–53). Moreover, Saci et al. have shown that, in serum-stimulated cells, Rac1 can act upstream of mTORC1 (as assessed by p70-S6K phosphorylation) independently of the PI3K-AKT pathway (43). Therefore, we analyzed the influence of Rac1 knockdown on p70-S6K phosphorylation as a readout of mTORC1 activity. Notably, the depletion of Rac1 led to a strong and significant inhibition of p70-S6K phosphorylation in METM1268T--expressing cells (Fig. 4C). Moreover, Rac1 knockdown also significantly reduced the anchorage-independent growth of these cells while having no effect on wild-type MET-expressing cells (Fig. 4D, fig. S4A). Rac1 knockdown also significantly reduced anchorage-independent growth of U87MG cells to a similar level seen in MET-knockdown cells (Fig. 4E and fig. S4, B and C). Together, these results identified Rac1 as a positive regulator of the mTOR pathway to mediate oncogenic MET-driven anchorage-independent growth.

Rac1 mediates anchorage-independent growth of MET-mutant cells independently of its GTPase activity

Depletion of Rac1 did not lead to a reduction of mTOR phosphorylation (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Rac1 regualtes the mTOR pathway in a manner other than phosphorylation-dependent activation of mTOR per se. We therefore investigated whether Rac1’s classical mode of function—its GTPase activity, which is activated by GEFs—mediates this oncogenic MET-induced anchorage-independent growth.

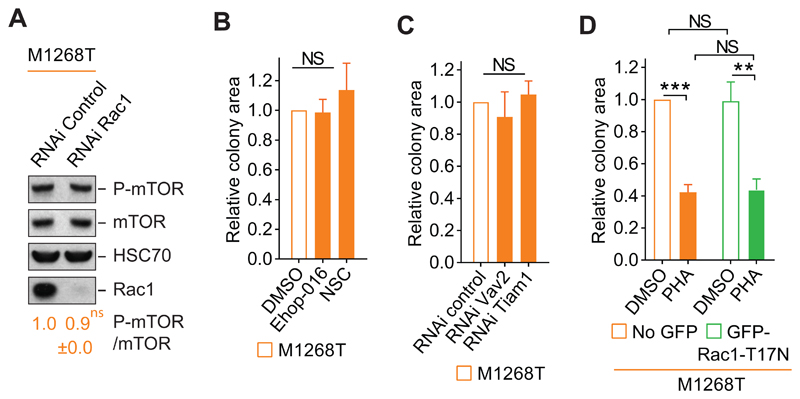

Fig. 5. Rac1 promotes anchorage-independent growth of MET-mutant cells independently of its GTPase activity.

(A) Western blots for phosphorylated mTOR on Ser2481 (P-mTOR), mTOR, HSC70 and Rac1 of M1268T Met-expressing cells transfected with negative control (RNAi control) or Rac1 (RNAi Rac1) siRNAs. Below, the mean levels of indicated phosphorylated protein over total protein ± SEM obtained by densitometry of Western blots. N=3 independent biological replicates. (B) Colony area of M1268T Met-expressing cells grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO, Ehop-016 (4 μM) or NSC23766 (NSC) (100 μM). N=3 independent biological replicates. (C) Colony area of M1268T MET-expressing cells transfected with control, Vav2 or Tiam1 siRNAs grown in soft agar. N=4 independent biological replicates. (D) Colony area of M1268T-MET-expressing cells transiently transfected with GFP-Rac1-T17N dominant-negative construct. After flow cytometry separation, the cells expressing GFP-Rac1-T17N or the GFP negative cells (no GFP) were grown in soft agar and were treated with DMSO or PHA-665752 (PHA) (100 nM), N=4 independent biological replicates. Data (A to E) are mean values +/- SEM. P values were obtained with the Student’s t test. NS: non-significant, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005.

We and others have reported that silencing the GEF Tiam1 reduces MET-dependent activation of Rac1 (26, 27) and that treatment with the pharmacological inhibitor NSC23766, which prevents binding between Tiam1 and Rac1 (54), reduces METM1268T-dependent cell migration (4). We have also shown that silencing the GEF Vav2 reduces MET-driven Rac activation and cell migration (4, 26). We show here that the pharmacological inhibitor Ehop-016, which prevents binding between Vav2 and Rac1 (55), reduced METM1268T-dependent Rac1 activation and subsequent cell migration (fig. S5, A and B). Treatment with Ehop-016 or NSC23766 had no significant effect on M1268T or wild-type MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth (Fig. 5B, and fig. S5, C and D). Similar results were obtained by knocking down Vav2 and Tiam1 (Fig. 5C, and fig. S5, E to G). These results indicate that these two GEFs are not part of the MET-Rac1-mTOR pathway regulating anchorage-independent growth, and further suggest that Rac1’s GTPase activity may not be required for oncogenic MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth.

Indeed the expression of a GFP-tagged dominant-negative mutant Rac1 (GFP-Rac1-T17N) (fig. S5H) did not modify anchorage-independent growth in METM1268T-expressing cells, and the cells remained sensitive to MET inhibition with PHA-665752 (Fig. 5D and fig. S5I). However, as expected, GFP-Rac1-T17N expression reduced the cells’ migration (fig. S5J), consistent with our data here (fig. S5B) and previously (4) that the GEFs are required for this function. Altogether these results indicate that the GTPase activity of Rac1 is dispensible for oncogenic MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth.

Rac1 mediates mutant MET-dependent localization of mTOR at the plasma membrane

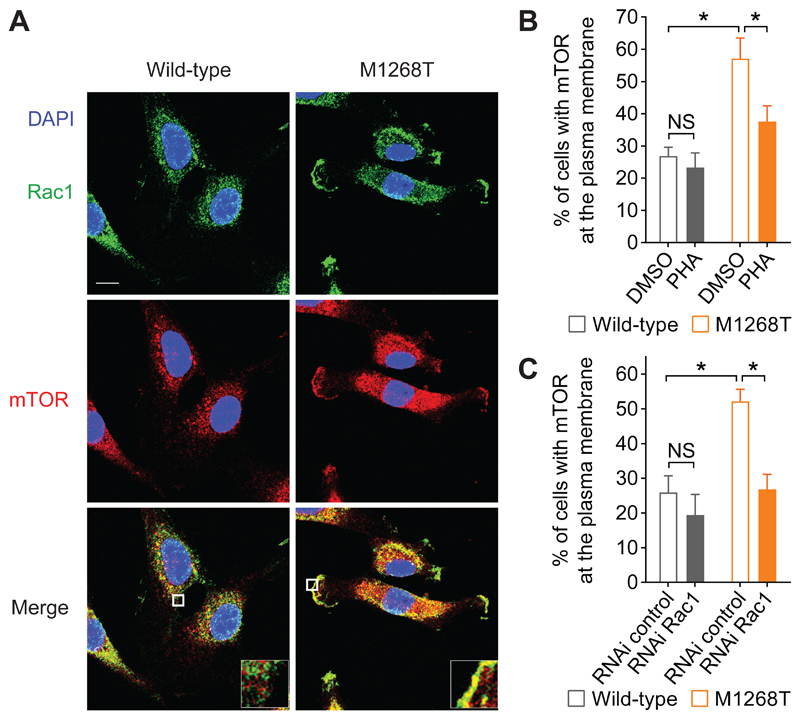

To further investigate how Rac1 controls mTOR pathway downstream of oncogenic Met in the stimulation of anchorage-independent growth, we analysed their cellular localization in wild-type and M1268T MET-expressing cells. We have previously demonstrated that METM1268T activity triggers a significant increase in the amount of Rac1 localized at the plasma membrane (4). Notably, compared with wild-type MET-expressing cells, a significantly higher percentage of METM1268T-expressing cells displayed mTOR at the plasma membrane (Fig. 6, A and B), similarly to Rac1 (Fig. 2C, and fig. S2, E and F). In METM1268T– but not wild-type–expressing cells, the localization of mTOR, as well as Rac1, at the plasma membrane was significantly reduced in response to the pharmacological MET inhibitor PHA-665752 (Fig. 6B, and fig. S2, E and F), indicating that, METM1268T activity induces mTOR localization to the plasma membrane. This was significantly prevented by RNAi-mediated knockdown of Rac1 (Fig. 6C). These results indicate that, rather than promoting mTOR activation per se, Rac1 mediates a change in mTOR’s localization.

Fig. 6. Rac1 is required for mutant MET-dependent localization of Rac1 and mTOR at the plasma membrane.

(A) Confocal sections of wild-type and M1268T MET-expressing cells. Scale bar: 10μm. Cells were fixed and stained with DAPI (blue) and immunostained for Rac1 (green) and mTOR (red). (B and C) Percentage of cells with mTOR at the plasma membrane when cells were (B) treated with DMSO or PHA-665752 (PHA, 100 nM) or (C) transfected with negative control or Rac1 siRNA. N=3 independent biological replicates. Data (B and C) are mean values ± SEM. P values were obtained with the Student’s t test. NS: non-significant, *P<0.05.

Through its C-terminal RKR motif, Rac1 promotes mTOR localization at the plasma membrane and anchorage-independent growth of MET-mutant cells

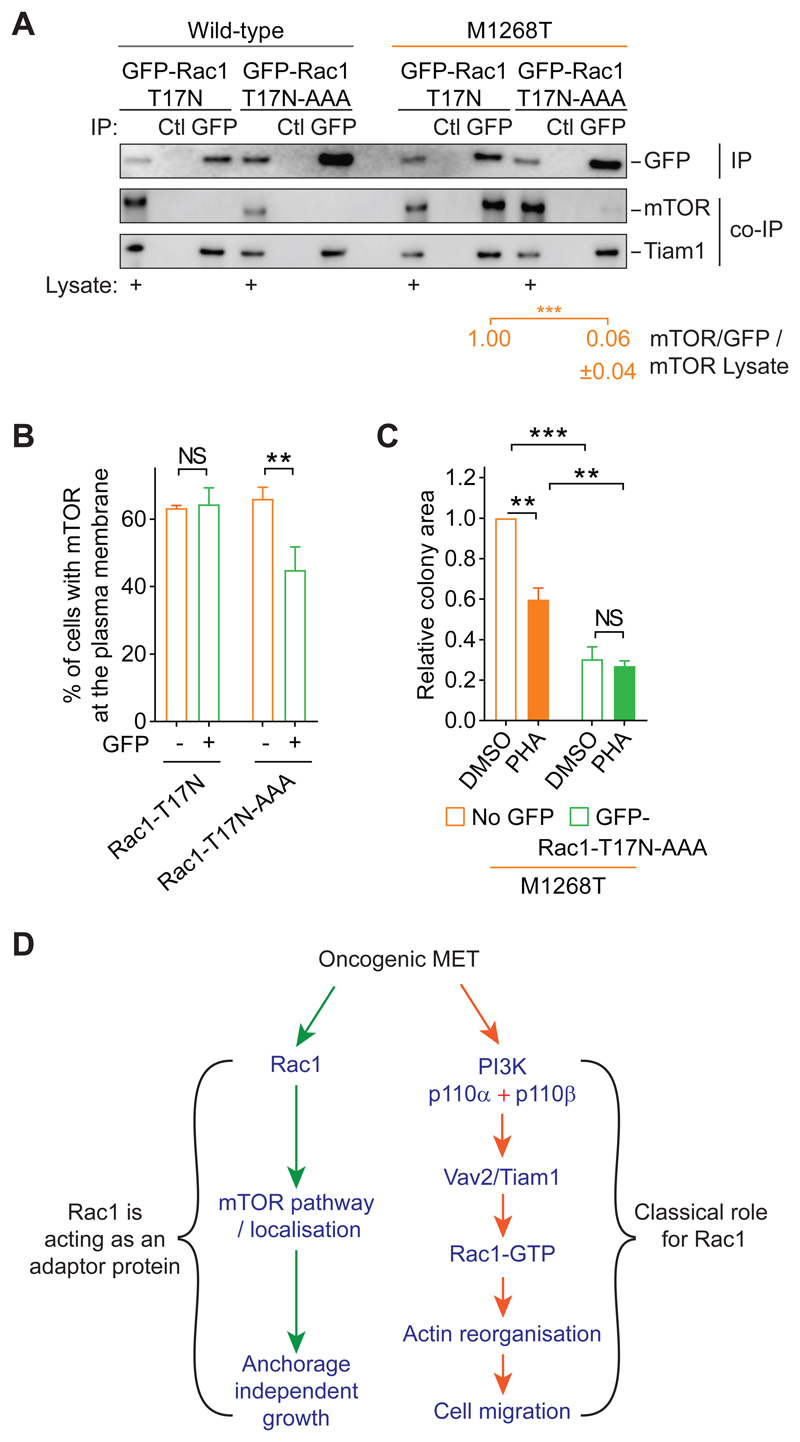

Rac1 and mTOR colocalization were observed at the plasma membrane as well as in the perinuclear area of METM1268TNIH3T3 cells (Fig. 6A), suggesting that the two molecules form a complex and that Rac1 may co-traffic with mTOR from perinuclear endosomes to the plasma membrane. We therefore investigated whether Rac1, regardless of its state of activation, forms a complex with mTOR downstream of mutant MET. mTOR co-immunoprecipitated with GFP-Rac1-T17N in METM1268T-but not wild-type MET-expressing cells (Fig. 7A). This result indicates that, indeed, Rac1 and mTOR form a complex independently from Rac1’s GTPase activity, and it is driven by METM1268T activity. It is also consistent with a previous study in cells stimulated by serum and which also reported that Rac1’s protein binding motif, RKR, in its C-terminal region interacts directly with mTOR (43). We therefore introduced the mutation AAA in place of the RKR motif in the construct GFP-Rac1-T17N. The resulting construct, GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA, did not co-immunoprecipitate with mTOR in METM1268T-expressing cells (Fig. 7A). However, GFP-Rac1-T17N or GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA were able to complex similarly with other proteins, such as the GEF Tiam1 (Fig. 7A), as expected (56). Thus, oncogenic mutant MET promotes mTOR association to the RKR motif of Rac1.

Fig. 7. Rac1 associates with and promotes plasma membrane localization of mTOR and anchorage-independent growth of MET-mutant cells through its C-terminal RKR motif.

(A) Wild-type and M1268T MET-expressing cells were transiently transfected with GFP-Rac1-T17N or GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA constructs. GFP-Rac1 was immunoprecipipated (IP) with GFP-Trap beads (GFP). Pull-down with control beads (Ctl) was performed. Western blots were performed to detect the GFP immunoprecipitates (IP) and the co-immunoprecipitated (co-IP) proteins mTOR and Tiam1. Lysates for each condition were also blotted and are indicated with “+”. Numbers below were obtained following densitometry of the blots. Thy represent the level of mTOR co-immunoprecipitated with GFP in M1268T MET-expressing cells. Thus, for each construct, mTOR level was normalised to GFP level. The obtained value was normalised to mTOR levels in lysate. The value was set as 1 for GFP-Rac1-T17N construct. Data are mean +/- SEM, N=3 independent biological replicates. (B and C) M1268T MET-expressing cells were transiently transfected with GFP-Rac1-T17N (B) or GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA (B and C) constructs. After flow cytometry separation, the cells expressing GFP or the GFP negative cells (No GFP) were (B) immunostained for mTOR and the percentage of cells with mTOR at the plasma membrane was evaluated, and (C) grown in soft agar and treated with DMSO or PHA-665752 (PHA, 100 nM). Data are mean +/- SEM, N=3 independent biological replicates. P values were obtained with the Student’s t test. NS: non-significant, **P<0.01, ***P<0.005. (D) Model suggested for the role of Rac1 downstream of oncogenic MET to induce cell migration, and anchorage-independent growth.

The expression of GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA, while not of GFP-Rac1-T17N, led to a significant reduction of the percentage of GFP-positive METM1268T-expressing cells that displayed mTOR at the plasma membrane (Fig. 7B, fig. S6A). These results suggest that the association of Rac1 with mTOR is required for mTOR translocation to the plasma membrane. Moreover, the expression of GFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA (Fig. 7C and fig. S6, A and B), unlike the expression of GFP-Rac1-T17N (Fig. 5D, figs. S5I and S6A), prevented MET-mutant-dependent anchorage-independent growth, with no further effect of MET inhibition with PHA-665752 (Fig. 7C, fig. S6B).

Altogether these results suggest an oncogeric MET pathway wherein Rac1 acts as an adaptor, through its protein binding motif RKR, to promote mTOR translocation to the plasma membrane and, consequently, its signaling there that stimulates anchorage-independent growth.

Discussion

PI3K and Akt have been described to mediate RTK driven growth, survival and migration, whereas Rac1 has been broadly recognized as a regulator of cell migration. Here, we report that Rac1 is a master regulator of oncogenic MET-dependent cell migration and anchorage-independent growth, while PI3K promotes oncogenic MET-dependent cell migration only. The classical class I PI3K-GEF-Rac1-GTP pathway promotes oncogenic mutant MET-dependent cell migration. However, by opposition to the classical RTK-PI3K-AKT-mTORC1 pathway (2, 3, 11, 19, 49), an unexpected Rac1-mTORC1 pathway, in which Rac1 plays an adaptor role triggering mTOR translocation to the plasma membrane, independent of Rac1 GTPase activity, promotes MET mutant-induced anchorage-independent growth.

Each pathway required intact endocytosis machinery, which is consistent with our previous findings suggesting that the shuttling of oncogenic MET mutants between the plasma membrane and endosomes is necessary to activate Rac1 signalling (4) (Fig. 7D).

Our findings also reveal that oncogenic MET-dependent cell migration required the class I PI3K isoforms, p110α and p110β, to activate Rac1 and induce actin reorganization and cell migration (Fig. 7D). It is now generally accepted that class I PI3K mediates RTK signaling, including that downstream of EGFR (57) or IGFR (16). However, the precise role and contribution of each isoform is not yet well understood, especially with regard to MET signaling. Class I-selective PI3K inhibitors, including isoform-specific, have been developed, many are being tested in clinical trials, some were approved (22, 58, 59). Targeting specific isoforms may improve the therapeutic response of cancer patients while reducing toxicity.

Conclusions from in vitro (cell culture) work implying the involvement of PI3K activity have often been drawn based on the use of LY294002 at high doses, from 10 to 50 μM. Although 10 μM is the minimal concentration necessary for its pan-PI3K inhibitory activity [except in the case of resistant class II PI3K (37)], mTOR is also directly inactivated (37). Here, using a set of specific mTOR and pan/class I PI3K inhibitors in addition to LY294002 at 10 μM, we demonstrate that, although PI3K is able to mediate oncogenic Met dependent mTOR signalling, MET dependent anchorage independent growth is mediated by mTOR, but not PI3K. One possibility is that the activation of mTOR promoted by PI3K does not occur at the right location in the cell to trigger oncogenic MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth. This hypothesis fits with our findings that, oncogenic MET activity leads to the formation of a complex between the Rac1 RKR motif (within its C-terminal polybasic region (63, 64)) and mTOR, leading to an increased localization of mTOR and Rac1 at the plasma membrane and, consequently, anchorage independent growth. Our results are consistent with those of Saci et al. (43) which demonstrate a PI3K-independent, but Rac1-dependent, mTOR pathway activation in the control of cellular size. Furthermore, our finding that mTOR inhibition reduced tumor growth in vivo, including that of MET inhibitor-resistant tumors (4), may have clinical relevance.

Rac1-GTPase activity was not required for anchorage-independent growth driven by METM1268T. This is consistent with the role of Rac1 as an adaptor molecule and with the non involvement of Vav2 and Tiam1, two GEFs which promoted MET-dependent Rac1 activation and subsequent cell migration (4, 26). The GEF p-REX-1 was previously shown to establish a link between mTOR and Rac leading to cell migration (62). However, given that its role is to promote mTOR-dependent Rac activation, it is unlikely to be involved in oncogenic MET-dependent anchorage-independent growth, which (in the cells used) did not require Rac1 activation. The revealed role of GTPase-independent Rac1 is consistent with the lack of requirement for class I PI3K in METM1268T-driven anchorage-independent growth, because PI3K classically promotes Rac1-GTPase activity through promoting the activation of GEFs that contain a PH-domain.

Although the perinuclear late endosome or lysosome is the classical site for mTORC1 localization and activation (65, 66), mTOR localization at the plasma membrane has been reported in a few studies (43, 67, 68). This mTOR location may enable the activation of specific mTOR substrates that are also localized at the plasma membrane. In addition to a plasma membrane localization, a punctate localization of Rac1 and mTOR were observed in the perinuclear area of the cells (Fig. 6A), suggesting perhaps co-trafficking of the two molecules to the plasma membrane from perinuclear endomembranes. Thus, mTOR may translocate to the plasma membrane within the lysosome to get activated locally (69) or from the perinuclear lysosome, post-activation, possibility trafficking with other members of the complex mTORC1. Consistent with the second hypothesis, Rac1 depletion reduced the phosphorylation of p70-S6K, a major mTORC1 effector, but had no effect on mTOR autophosphorylation site Ser2481, which we found was activated by oncogenic MET (Fig. 3D). Although there is not a consensus for the use of mTOR phospho-sites as a clear read-out of mTORC1 in an active state (70, 71), Ser2481 has been used to monitor intrinsic mTORC catalytic activity (72).

Our findings may have important implication in the clinic. We speculate that targeting mTORC1 may reduce tumor growth, whereas targeting class I PI3K may benefit patients by inhibiting tumor invasion or metastasis. Therefore, the strategy of targeting both class I PI3K and mTOR with dual inhibitors could be therapeutically beneficial in cancer patients with MET-mutant tumors.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for western blotting: Rabbit polyclonal antibodies targeting phosphorylated MET (Tyr1234-Tyr1235; #3126), phosphorylated AKT (Ser473, #9271), AKT (#9272), phosphorylated p70-S6K (Thr389, #9205), phosphorylated p70-S6K (Thr421/Ser424, #9204), p70-S6K (#9202), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (#9101), ERK1/2 (#9102S), phosphorylated mTOR (Ser2481, #2974), and rabbit monoclonal antibodies targeting mTOR (#2983), and p110α (#4249) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (all used at 1:1000). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against murine MET (B-2; 1:500, #sc-8057), HSC70 (1:5000, #sc7298), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against p110β (1:500, #sc-602) and Vav2 (1:1000, #sc-H200) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The antibodies targeting tubulin (mouse monoclonal, 1:5000, #62204) and human MET (CVD13; rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000, #182257) were purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies. The antibodies targeting Tiam1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000, #ABN1488) and Rac1 (mouse monoclonal, 1:500, #ARC03) were purchased from Merck and Cytoskeleton, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibodies, sheep anti-mouse and donkey anti-rabbit, were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (VWR International; used at 1:5000). For immunofluorescence, the antibody targeting Rac1 (mouse monoclonal, 1:100, #05-389) was purchased from Merck Millipore and mTOR (rabbit monoclonal, 1:50, #2983) from Cell Signaling Technology. F-actin was stained using Alexa Fluor®-546 phalloidin (Molecular probes, Life Technologies; used at 1:500). Cy3-coupled donkey anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch) was used as secondary antibody (1:500).

Pharmacological inhibitors

MET inhibitors PF-02341066 (100 nM, used in U87MG cells) and PHA-665752 (100 nM, used in NIH3T3 cells), dynasore (80 μM), and Ehop-016 (4 μM) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. LY294002 (10 μM) was purchased from Calbiochem. UO126 (10 μM) was purchased from Cell signalling. Wortmannin (100 nM), A66 (500 nM), TGX221 (40 nM), GDC0941 (100 nM to 10 μM), rapamycin (2 nM), and NSC23766 (100 μM) were purchased from Selleckchem. Stock dilutions of each were prepared in DMSO.

Constructs

The plasmid pEGFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA was generated from the plasmid pEGFP-Rac1-T17N, a Rac1 dominant-negative mutant, gift from Prof. Maddy Parsons (King’s College London), as follows: Rac1-T17N-AAA sequence (table S1), with NotI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites at 5’ and 3’ ends respectively, was generated and subcloned into a pMA vector by GeneArt gene synthesis (Thermo Scientific). The Rac1-T17N-AAA sequence was then amplified using M13-20 primer pair (M13-20 Forward: TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAG; M13-20 Reverse: GGAAACAGCTATGACCATG), and the resultant fragment was inserted into pEGFP-Rac1-T17N using NotI and EcoRI digestion followed by ligation, thereby replacing the Rac1-T17N sequence. Sanger sequencing was performed on single colony to confirm the insertion of correct sequence.

Cell lines and cell culture

The mouse fibroblast NIH3T3 cell lines expressing either murine wild-type, M1268T, or D1246N MET (4), were a gift from Prof. G. Vande Woude (Van Andel Institute) (73). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 4.5 g/L of glucose and L-glutamine, supplemented with 10% donor calf serum (DCS, from Gibco, Life Technologies). NIH3T3 cells were starved in DMEM supplemented with 1% DCS for 24 hours prior to migration assays, and serum-starved with 0% DCS in DMEM for 1 hour for Western blot analysis unless otherwise stated. The gliomablastoma cells U87MG were purchased from ATCC and cultured in α-Minimum Essential Modified Eagle’s medium (α-MEM) containing 1 g/L of D-glucose and 292 mg/L L-glutamine, supplemented with 10% FBS. U87MG cells were starved for 24 hours in FBS-free α-MEM for migration assays and Wstern blots. Cell lines were maintained in humidified incubators at 37°C and 5-8% CO2 and were passaged every three days. Cells were not used beyond passage 10 to ensure experimental consistency.

Cell transfection

NIH3T3 cells were transfected with siRNA (Qiagen and Dharmacon; targets and sequences of the oligonucleotides are listed in table S1) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher) or Amaxa® Nucleofector® technology following the manufacturer’s instructions (Lonza). The kit “R” and the program of nucleofection “U-030” were used for NIH3T3 cells. U87MG cells were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (ThermoFisher). Cells were harvested 48 hours after RNAi transfection.

The vectors pEGFP-Rac1-T17N or pEGFP-Rac1-T17N-AAA were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000. After 24 hours, the GFP positive cells were separated from the GFP negative cells on a high speed MoFlo Astrios cell sorter (Beckman Coulter). Both type of cells collected (GFP negative and GFP positive cells) were used and compared to each other in Transwell chemotactic migration assay, soft agar assay, and immunofluorescence assay. For the GFP immunoprecipitation assay, the cells were lysed 24 hours after transfection and did not required GFP cell sorting.

Western Blotting

To prepare total cellular proteins, 100,000 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to attach for 24 hours in complete medium. Cells were treated with pharmalogical inhibitors for 1 hour unless otherwise stated. When required, NIH3T3 cells were treated with dynasore for 30 min. Cells were harvested in radio-immunoprecipitation buffer (RIPA) or in 2X Sample buffer (Invitrogen, Life Technologies) containing 200 mM DTT, and boiled for 5 min. To perform the SDS-page, equal quantities of total cellular proteins from each sample were loaded either onto 4-12% gradient polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen) or 10% acrylamide gels containing sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS-PAGE). Protein sizes were determined by comparison to a set of standards, Molecular Weight Marker Full Range Rainbow™ (RPN800E Recombinant Protein, from GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and Novex® Sharp Pre-stained Protein Standard (Invitrogen, Life Technologies). To perform the protein immunoblot, proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (GE healthcare). Primary antibodies, were diluted in 5% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20 Tris Buffer (TBS-T), and incubated overnight at 4°C. Specific binding of antibodies was detected with appropriate HRP-coupled secondary antibodies and visualized using ECL reagent (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Protein expression levels were analysed and compared by densitometry. To quantify the protein bands, we performed densitometry on non-saturated bands using ImageJ software to evaluate and compare the intensities of protein expression. Relative protein phosphorylation levels were obtained by normalizing the amount of phosphorylated protein to that of total protein, while the expression of total proteins were normalized to tubulin or HSC70 levels from the same membrane.

Transwell chemotactic migration assays

Cells were serum-deprived for 24 hours prior to the experiment. Transwell filters (Corning, 8 μm pore size) were coated with fibronectin (Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min and dried. Harvested cells were suspended in 0.1% BSA/serum free media at 45,000 cells/mL with the appropriate drug where indicated. 200 μL of the cell suspension (9x103 cells) was added to the upper chamber of each Transwell insert, while complete medium was added to the lower chamber to create a chemoattractant gradient. Cells were allowed to migrate at 37°C for 90 min. After this time, cells on the top of the filters, which had not migrated, were removed with a wet cotton bud. The remaining migrated cells (on lower side of the membrane) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Cell nuclei were stained with haematoxylin (Sigma Aldrich). Filters were mounted onto a glass slide with Aqueous medium (Aquatex, VWR). Migrated cells were counted by microscopy at x20 with a Zeiss Axiophot microscope. Ten fields were counted per membrane, and each condition was performed in triplicate in each experiment.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

13 mm coverslips were placed into the wells of 24-well plates. 20,000 NIH3T3 cells were seeded on poly-L-Lysine pre-coated coverslips (BD BioCoat™, BD Biosciences) and allowed to attach for 24 hours. Cells were then treated with appropriate drugs for 1 hour. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA. Excess PFA was quenched by incubation with 50 mM of ammonium chloride (NH4Cl). PBS containing 3% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma Aldrich) was used for membrane permeabilization and blocking non-specific sites. Primary antibodies were diluted at 1:100 in 3% BSA/PBS and, incubated for 40 min. To visualize the actin cytoskeleton, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor®-546 phalloidin (Molecular probes, Life Technologies) at 1:500 for 20 min during secondary incubation. Secondary antibodies, diluted at 1:500 in 3% BSA/PBS were incubated for 20 min, followed by sequential washing in PBS, then distilled water prior to mounting with the Prolong® Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Life Technologies). Immunofluorescence was detected and captured using a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope, fitted with a Plan-Apochromat oil immersion objective lens (63x/1.4). Cy3 and Alexa Fluor® 546 fluorochrome were excited at 543 nm wavelength by HeNe laser and emitted at 568 nm (red). Each image represents a single section of 0.7 μm thickness of the basal section of cells for phalloidin staining or the middle section of cells for Rac1 staining. The counting of cells in which Rac1 was present at the plasma membrane and those that lacked actin stress fibres were performed as previsouly described (4), directly at the microscope by the investigator. For each condition within each independent biological replicate, multiple fields spread across the coverslip were counted, avoiding fields on the edge of the coverslip due to the cells being damaged at this location. Picture fields were chosen randomly based on DAPI staining and all cells comprised in a field were counted. In total at least 100 cells per conditions and per experiments were counted. Cells were counted as positive for the presence of Rac1 at the plasma membrane or for the absence of actin stress fibres.

Adhesion assay

96-well plates (Perkin Elmer) were precoated with fibronectin (Sigma Aldrich) for 30 min and air-dried. 4,500 cells were seeded per well in complete medium supplemented with DMSO or pharmalogical inhibitors. The cells were allowed to attach for 50 min at 37°C and 5% CO2 in humidified incubators. The wells were then washed in PBS and fixed with 4% PFA. The nucleus of each adherent cell was then stained by Hoechst 33342 (ThermoFisher). Hoechst 33342 signal was imaged by Celigo (Nexcelom Bioscience). Each condition was performed in triplicate. The total number of cells per well was counted by ImageJ software.

Rac1 activation assay

Rac1-GTP was precipitated using the GST-CRIB domain of PAK1 with the Rac1 Activation Assay Biochem Kit (Cytoskeleton), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bound Rac1-GTP was detected by Western blot with antibody to Rac1.

GFP immunoprecipitation

GFP immunoprecipitation was carried out using GFP-Trap magnetic agarose beads (Chromotek) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the exception of the coIP lysis buffer that was replaced by RIPA-CHAPS buffer [10 mM Tris pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 0,5 mM EDTA; 0.5% v/v CHAPS; 1 mM PMSF; 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate; 1 mM β-glycerophosphate; 1 mM Na3 VO4; proteinase inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich); 250U/ml benzonase (Sigma-Aldrich)]. Binding control magnetic agarose beads (Chromotek) were used for pull-down specificity control. Proteins precipitated with GFP-tagged bait proteins were detected by Western blotting.

Soft agar assay

500 NIH3T3 cells or 10,000 U87MG cells in single cell suspensions were mixed with 5 mL 0.3% agarose (type IX-A, Sigma Aldrich)/medium per condition and placed on ice to solidify. After 18 min, 1 mL of complete medium was added to the top of the agar and cells were cultured for 5 days. Then, treatment was started and the medium was changed daily for 4 days. 1000 NIH3T3 cells or 10,000 U87MG cells transfected with RNAis were either immediately placed into agarose following transfection with Amaxa or after 18 hours following transfection with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX, for 9 days. Pictures were taken of the whole wells using a Zeiss, Stemi SV11 microscope or Celigo (Nexcelom Bioscience). The total area and number of the colonies were measured with ImageJ software.

Tumorigenesis assay

Tumorigenesis assays were performed as previously (4). Briefly, female athymic nude mice (CD1 Nu/Nu, Charles River UK) at 4 to 6 weeks old were used in accordance with the United Kingdom Coordination Committee on Cancer Research guidelines and Home Office regulations. A cell suspension of 5 x 10 wild-type or METM1268T-NIH3T3 expressing 6 cells/mL was prepared is PBS and 100 μL was injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse. Tumor volumes were measured daily using callipers and the volumes were calculated as follows:

Once the tumors reached the volume of 50 mm3, they were tr.eated with 100 μL of the indicated treatment. DMSO was used as the vehicle/negative control. Reagents were applied topically on the skin over the tumor and surrounding area. Once tumors then reached 500 mm3, mice were euthanized by neck dislocation Each treatment group consisted of 5 mice.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data of the indicated number of independent biological replicates (“N=” in figure legends) are expressed as means ± S.E.M. A Student’s t-test two-tailed distribution and two-sample equal variance was used to test the significance of most results obtained.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. G. Vande Voude, from the Van Andel Institute, for his gift of the NIH3T3 cell lines expressing murine Met. We thank Prof. Bart Vanhaesebroeck, from UCL Cancer Institute, for the discussions and guidance throughout the study. We thank Prof. Ian Hart, from Barts Cancer Institute, for critically reading the manuscript.

Funding

A.H. was a recipient of a CR-UK studentship (C236/A11795), a Bayer4Target grant, and an ICR funded postdoctoral fellowship; S.F.H. of a grant from Pancreatic Cancer Research Fund; R.B.M. of a UK Medical Research Council (MRC) studentship, a MRC Centenary Award and a grant from Rosetrees Trust (M314); C.J. was a recipient of a Barts and The London Charitable Foundation Scholarship (RAB 05/PJ/07); and L.M. of Breast Cancer Now (2008NovPR10) and Rosetrees Trust grants (M346). C.Z. and P.A.C. work was supported by CR-UK grant C309/A11566. S.K was recipient of an MRC Project grant (MR/R009732/1).

Footnotes

Author contributions: A.H. performed most of the in vitro experiments, and analyzed all the experiments. S.F.H., C. Z., L.M. and C.J. performed some in vitro experiments. A.H. and R.B.M. performed the in vivo mice experiments. S.K. conceived and directed the project, and designed the experiments. A.H. and S.K. wrote the manuscript. P.A.C. critically reviewed and improved the manuscript.

Competing interests: A.H., C.Z., S.F.H., and P.A.C. are employees of The Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), which has a commercial interest in the discovery and development of PI3K inhibitors, including GDC0941 (Pictilisib), and operates a rewards-to-inventors scheme. P.A.C. has been involved in a commercial collaboration with Yamanouchi (now Astellas Pharma) and with Piramed Pharma developing PI3K inhibitors and intellectual property arising from the program was licensed to Genentech. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials.

References

- 1.Guadamillas MC, Cerezo A, Del Pozo MA. Overcoming anoikis--pathways to anchorage-independent growth in cancer. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3189–3197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.072165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C, Vande Woude G. Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:89–103. doi: 10.1038/nrc3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaumann AK, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Are they real tumor killers? Int J Cancer. 2016;138:540–554. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joffre C, et al. A direct role for Met endocytosis in tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:827–837. doi: 10.1038/ncb2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comoglio PM, Giordano S, Trusolino L. Drug development of MET inhibitors: targeting oncogene addiction and expedience. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2008;7:504–516. doi: 10.1038/nrd2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cepero V, et al. MET and KRAS gene amplification mediates acquired resistance to MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7580–7590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fong JT, et al. Alternative signaling pathways as potential therapeutic targets for overcoming EGFR and c-Met inhibitor resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. PloS one. 2013;8:e78398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qi J, et al. Multiple mutations and bypass mechanisms can contribute to development of acquired resistance to MET inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1081–1091. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott U, Pusapati RV, Christensen JG, Gray NS, Settleman J. Acquired resistance of non-small cell lung cancer cells to MET kinase inhibition is mediated by a switch to epidermal growth factor receptor dependency. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1625–1634. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campa CC, Ciraolo E, Ghigo A, Germena G, Hirsch E. Crossroads of PI3K and Rac pathways. Small GTPases. 2015;6:71–80. doi: 10.4161/21541248.2014.989789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vanhaesebroeck B, Stephens L, Hawkins P. PI3K signalling: the path to discovery and understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:195–203. doi: 10.1038/nrm3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nature reviews Genetics. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baer R, et al. Pancreatic cell plasticity and cancer initiation induced by oncogenic Kras is completely dependent on wild-type PI 3-kinase p110α. Genes & development. 2014;28:2621–2635. doi: 10.1101/gad.249409.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogt PK, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase: the oncoprotein. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2010;347:79–104. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang S, Denley A, Vanhaesebroeck B, Vogt PK. Oncogenic transformation induced by the p110beta, -gamma, and -delta isoforms of class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1289–1294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510772103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benistant C, Chapuis H, Roche S. A specific function for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase alpha (p85alpha-p110alpha) in cell survival and for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase beta (p85alpha-p110beta) in de novo DNA synthesis of human colon carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:5083–5090. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanhaesebroeck B, et al. P110delta, a novel phosphoinositide 3-kinase in leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4330–4335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vanhaesebroeck B, Guillermet-Guibert J, Graupera M, Bilanges B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:329–341. doi: 10.1038/nrm2882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan TL, Cantley LC. PI3K pathway alterations in cancer: variations on a theme. Oncogene. 2008;27:5497–5510. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fruman DA, Rommel C. PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2014;13:140–156. doi: 10.1038/nrd4204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hervieu A, Kermorgant S. The role of PI3K in Met driven cancer: a recap. Front Mol Biosci. 2018;5 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2018.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe LM, Yuzugullu H, Zhao JJ. PI3K in cancer: divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;15:7–24. doi: 10.1038/nrc3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sahai E, Marshall CJ. RHO-GTPases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:133–142. doi: 10.1038/nrc725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPase signalling in cell migration. Current opinion in cell biology. 2015;36:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridley AJ, Comoglio PM, Hall A. Regulation of scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor responses by Ras, Rac, and Rho in MDCK cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1110–1122. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menard L, Parker PJ, Kermorgant S. Receptor tyrosine kinase c-Met controls the cytoskeleton from different endosomes via different pathways. Nature communications. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4907. 3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palamidessi A, et al. Endocytic trafficking of Rac is required for the spatial restriction of signaling in cell migration. Cell. 2008;134:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fritsch R, et al. RAS and RHO families of GTPases directly regulate distinct phosphoinositide 3-kinase isoforms. Cell. 2013;153:1050–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmidt L, et al. Germline and somatic mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the MET proto-oncogene in papillary renal carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1997;16:68–73. doi: 10.1038/ng0597-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie Q, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) autocrine activation predicts sensitivity to MET inhibition in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:570–575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119059109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potempa S, Ridley AJ. Activation of both MAP kinase and phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase by Ras is required for hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-induced adherens junction disassembly. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2185–2200. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khwaja A, Lehmann K, Marte BM, Downward J. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase induces scattering and tubulogenesis in epithelial cells through a novel pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18793–18801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao GH, et al. Anti-apoptotic signaling by hepatocyte growth factor/Met via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:247–252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011532898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen JG, et al. A selective small molecule inhibitor of c-Met kinase inhibits c-Met-dependent phenotypes in vitro and exhibits cytoreductive antitumor activity in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63:7345–7355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schenck A, et al. The endosomal protein Appl1 mediates Akt substrate specificity and cell survival in vertebrate development. Cell. 2008;133:486–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gharbi SI, et al. Exploring the specificity of the PI3K family inhibitor LY294002. Biochem J. 2007;404:15–21. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kong D, Dan S, Yamazaki K, Yamori T. Inhibition profiles of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors against PI3K superfamily and human cancer cell line panel JFCR39. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 2010;46:1111–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Workman P, Clarke PA, Raynaud FI, van Montfort RL. Drugging the PI3 kinome: from chemical tools to drugs in the clinic. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2146–2157. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raynaud FI, et al. Biological properties of potent inhibitors of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases: from PI-103 through PI-540, PI-620 to the oral agent GDC-0941. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1725–1738. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arcaro A, Wymann MP. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J. 1993;296(Pt 2):297–301. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powis G, et al. Wortmannin, a potent and selective inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2419–2423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bain J, et al. The selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors: a further update. Biochem J. 2007;408:297–315. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saci A, Cantley LC, Carpenter CL. Rac1 regulates the activity of mTORC1 and mTORC2 and controls cellular size. Mol Cell. 2011;42:50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang SA, et al. mTORC1 phosphorylation sites encode their sensitivity to starvation and rapamycin. Science. 2013;341 doi: 10.1126/science.1236566. 1236566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis complex-2 tumor suppressor gene product tuberin as a target of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/akt pathway. Mol Cell. 2002;10:151–162. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moumen A, Patane S, Porras A, Dono R, Maina Fl. Met acts on Mdm2 via mTOR to signal cell survival during development. Development (Cambridge, England) 2007;134:1443–1451. doi: 10.1242/dev.02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barrow-McGee R, Kishi N, Joffre C. Beta 1-integrin-c-Met cooperation reveals an inside-in survival signalling on autophagy-related endomembranes. 2016;7 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11942. 11942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villalonga P, Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and cell cycle control. Growth factors (Chur, Switzerland) 2006;24:159–164. doi: 10.1080/08977190600560651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kumper S, et al. Rho-associated kinase (ROCK) function is essential for cell cycle progression, senescence and tumorigenesis. eLife. 2016;5:e12994. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orgaz JL, Herraiz C, Sanz-Moreno V. Rho GTPases modulate malignant transformation of tumor cells. Small GTPases. 2014;5:e29019. doi: 10.4161/sgtp.29019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gao Y, Dickerson JB, Guo F, Zheng J, Zheng Y. Rational design and characterization of a Rac GTPase-specific small molecule inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7618–7623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307512101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Montalvo-Ortiz BL, et al. Characterization of EHop-016, novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac GTPase. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13228–13238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Worthylake DK, Rossman KL, Sondek J. Crystal structure of Rac1 in complex with the guanine nucleotide exchange region of Tiam1. Nature. 2000;408:682–688. doi: 10.1038/35047014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roche S, Koegl M, Courtneidge SA. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase alpha is required for DNA synthesis induced by some, but not all, growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:9185–9189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rodon J, Tabernero J. Improving the Armamentarium of PI3K Inhibitors with Isoform-Selective Agents: A New Light in the Darkness. Cancer discovery. 2017;7:666–669. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Janku F, Yap TA, Meric-Bernstam F. Targeting the PI3K pathway in cancer: are we making headway? Nature reviews Clinical oncology. 2018;15:273–291. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bi L, Okabe I, Bernard DJ, Wynshaw-Boris A, Nussbaum RL. Proliferative defect and embryonic lethality in mice homozygous for a deletion in the p110alpha subunit of phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10963–10968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ciraolo E, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110beta activity: key role in metabolism and mammary gland cancer but not development. Sci Signal. 2008;1:ra3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.1161577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hernandez-Negrete I, et al. P-Rex1 links mammalian target of rapamycin signaling to Rac activation and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23708–23715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Hennik PB, et al. The C-terminal domain of Rac1 contains two motifs that control targeting and signaling specificity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39166–39175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Das S, et al. Single-molecule tracking of small GTPase Rac1 uncovers spatial regulation of membrane translocation and mechanism for polarized signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:E267–276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409667112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sancak Y, et al. The Rag GTPases bind raptor and mediate amino acid signaling to mTORC1. Science. 2008;320:1496–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1157535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sancak Y, et al. Ragulator-Rag complex targets mTORC1 to the lysosomal surface and is necessary for its activation by amino acids. Cell. 2010;141:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martin TD, et al. Ral and Rheb GTPase activating proteins integrate mTOR and GTPase signaling in aging, autophagy, and tumor cell invasion. Mol Cell. 2014;53:209–220. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou X, et al. Dynamic Visualization of mTORC1 Activity in Living Cells. Cell reports. 2015;10:1767–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hong Z, et al. PtdIns3P controls mTORC1 signaling through lysosomal positioning. J Cell Biol. 2017;216:4217–4233. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201611073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dibble CC, Cantley LC. Regulation of mTORC1 by PI3K signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:545–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Copp J, Manning G, Hunter T. TORC-specific phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR): phospho-Ser2481 is a marker for intact mTOR signaling complex 2. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1821–1827. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soliman GA, et al. mTOR Ser-2481 autophosphorylation monitors mTORC-specific catalytic activity and clarifies rapamycin mechanism of action. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7866–7879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jeffers M, et al. Activating mutations for the met tyrosine kinase receptor in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11445–11450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.