Abstract

Background

In democracies, voting is an important action through which citizens engage in the political process. Although elections are only one aspect of political engagement, voting sends a signal of support or dissent for policies that ultimately shape the social determinants of health. Social determinants subsequently influence who votes and who does not. Our objective is to examine the existing research on voting and health and on interventions to increase voter participation through healthcare organizations.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to examine the existing research on voting, health, and interventions to increase voter participation through healthcare organizations. We carried out a search of the indexed, peer-reviewed literature using Ovid MEDLINE (1946–present), PsychINFO (1806–present), Ebsco CINAHL, Embase (1947–present), Web of Science, ProQuest Sociological Abstracts, and Worldwide Political Science Abstracts. We limited our search to articles published in English. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, followed by a full-text review of eligible articles and data extraction. Articles were required to focus on the connection between voting and health, or report on interventions that occurred within healthcare organizations that aimed to improve voter engagement.

Results

Our search identified 2041 citations, of which 40 articles met our inclusion criteria. Selected articles dated from 1991–2018 and were conducted primarily in Europe, the USA, and Canada. We identified four interrelated areas explored in the literature: (1) there is a consistency in the association between voting and health; (2) differences in voter participation are associated with health conditions; (3) gaps in voter participation may be associated with electoral outcomes; and (4) interventions in healthcare organizations can increase voter participation.

Conclusion

Voting and health are associated, namely people with worse health tend to be less likely to engage in voting. Differences in voter participation due to social, economic, and health inequities have been shown to have large effects on electoral outcomes. Research gaps were identified in the following areas: long-term effects of voting on health, the effects of other forms of democratic engagement on health, and the broader impact that health providers and organizations can have on voting through interventions in their communities.

Keywords: Voting, Political participation, Democratic engagement, Self-rated health, Health inequities, Social determinants of health

Background

The idea that health is strongly determined by social factors and processes—what we now call the social determinants of health—has long been a central idea within public health [1]. All social determinants of health are shaped by the distribution of power and resources within societies and at a global level [2, 3]. A number of processes influence this distribution of power and resources, including constitutions that define the rights and responsibilities of citizens and governments, policies that determine the minimum wage, work conditions, and social assistance, as well as the budgetary decisions that direct resources toward (or away from) education, child development, housing, and social services.

In democracies, citizens can play a variety of roles in the processes that shape the social determinants. Voting is one key aspect of democratic engagement, defined as “a multi-faceted phenomenon that embraces citizens’ involvement with electoral politics, their participation in ‘conventional’ extra-parliamentary political activity, their satisfaction with democracy and trust in state institutions, and their rejection of the use of violence for political ends” [4]. More simply, democratic engagement is “the state of being engaged in advancing democracy through political institutions, organizations, and activities” [5]. Democratic engagement can include electoral participation (voting, campaign displays, volunteer, campaign contributions), expressing a political voice (protest, boycott, contacting officials), having political knowledge/awareness (following government affairs, watching/reading/listening to news, talking about politics), and holding certain attitudes (promoting common good, affirming common humanity) [5].

The effect of voting on the social determinants of health is multi-factorial and complex. In a simple conceptualization, when larger numbers of people from certain communities and groups participate in voting, it translates into greater influence over determining who holds political power. Those in power in turn put forward and support policies that respond to the needs and demands of their constituents that shape the social determinants of their health. Not only does voting partially decide who forms government in democracies, and subsequently what policies shape social determinants, but the relationship may work in the opposite direction as well, in that the social determinants of health affect voting patterns. For example, socioeconomic status is associated with the likelihood of voting. Across many contexts, having a low income and a lower level of education is associated with lower rates of voting during elections [6–8]. Numerous theories explain this association including decreased social trust, diminished social capital, fewer chances to vote, and weakened educational opportunities about the policy process [7, 8].

Public health scholars have been called upon to better understand the functioning of politics at national and sub-national levels—and the mechanisms that connect politics to public health [9]. Our objective in this scoping review was to examine the existing research on voting and health, and on interventions to increase voter participation through healthcare organizations. We sought to understand the following questions: What is the relationship between voting and individual health? What healthcare-based interventions exist to support voting, and what have been their outcomes?

Methods

We conducted a scoping review with the central objective of identifying the existing peer-reviewed research on the association between voting and health, and on interventions that aim to increase voter participation through healthcare organizations [10, 11]. Voting was used as a proxy for democratic engagement in this scoping review as it is easily identifiable, measurable, and is an essential and defining characteristic of healthy democracies. We chose to focus on healthcare-based interventions, to explore the role that the health sector—which has frequent contact with large numbers of individuals from communities with relatively lower rates of voting—can play in supporting voting. We searched Ovid Medline (1946–present), PsychINFO (1806–present), Ebsco CINAHL, Embase (1947–present), Web of Science, Proquest Sociological Abstracts, and Proquest Worldwide Political Science Abstracts in March 2018. We used a broad search expression (Additional file 1, Additional file 2) in order to include as many articles as possible. Our search timeframes were chosen to include the full scope of articles available on each research platform. We limited our search to the peer-reviewed, indexed literature in English. The titles and abstracts of citations identified were reviewed independently against our inclusion and exclusion criteria by two authors (CB, DR), followed by review of the full-text articles. In this scoping review, we did not perform backward reference tracking.

We included peer-reviewed articles where the main focus was the relationship or association between voting and individual health, or focused on interventions in healthcare settings aimed at increasing voter participation. We excluded articles solely focused on the links between health and other forms of democratic engagement (ex. activism, protest) to focus more narrowly on the link between the act of voting and health.

After our initial review of full-text articles to ensure they met our inclusion and exclusion criteria, two authors (CB, DR) completed data extraction. We extracted information on the geographic location and context, area of focus, the effect size, measures used, and confounding variables. We prepared summaries for each article on the key themes and findings in one shared document, and then the entire study team reviewed these summaries and identified common overarching themes relevant to our review objectives.

Results

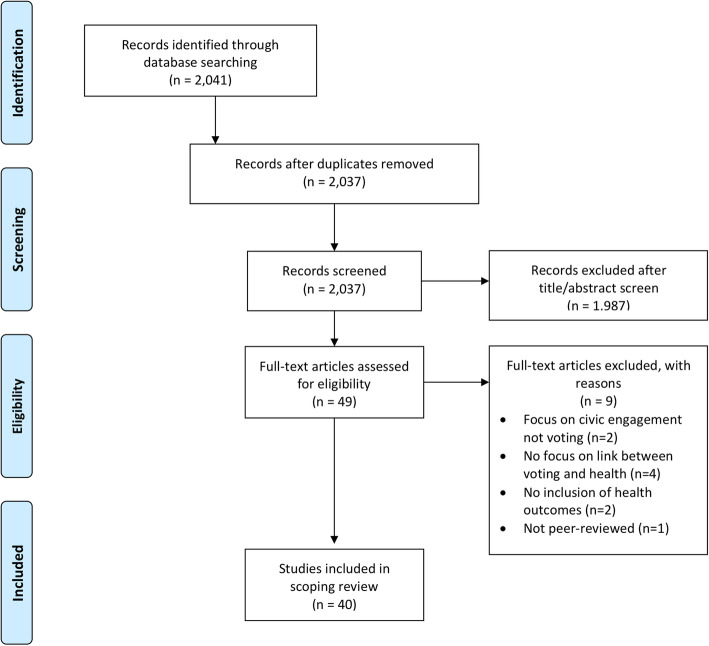

Our initial search identified 2041 citations (Fig. 1), and after reviewing titles and abstracts, 49 articles met our inclusion criteria. Following full-text review, 40 articles were included in the final analysis (Table 1). As we put in place a broad search strategy, many articles were not relevant to the research questions. Most of those were articles that focused on subjects like healthcare policy, democratic engagement (activism, civic engagement), voting patterns, political engagement, and health equity more broadly without actually discussing the link between voting and health or describing healthcare interventions in the voting process. The included articles were published in a diversity of research disciplines (classified according to journal and study design): health science (geriatrics, pediatrics, psychiatry), public health and epidemiology, political science, and social science. Most of the research was done in high-income countries, with a focus on Europe, the USA, and Canada. Although most of the research has been more recent, with 27 articles being written from 2010–present, the articles included were published between 1991 and 2018. Study designs included cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case studies, qualitative studies, literature reviews, and critical commentaries.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 1.

Articles identified that examine voting, health, and interventions in healthcare settings

| Authors (year) | Geographic location | Topic area | Main findings | Measures | Confounders addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albright et al. (2016) [12] | Colorado, USA | Association between health and voting |

Negative association between health risk behavior (smoking) and voting in the national US election Daily smokers were 60% less likely to vote than nonsmokers (OR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.27% to 0.54%). |

Self-reported smoking status; self-reported voting in the 2004 national US election | Sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, employment status, marital status, household income relative to the federal poverty level, and self-reported general health status |

| Arah (2008) [13] | Britain | Association between health and voting |

Study demonstrates effect of voting abstention in the UK general election and socioeconomic status on self-reported health Abstaining from voting in 1979, 1981, 1997 and 2001 increased odds of poor health in 1981 (1.56, 95% CI 1.36 to 1. 79), 1991 (1.37 95% CI 1.18 to 1.60), 2000 (1. 45, 95% CI 1.28 to 1.66), and 2004 (1.30, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.51). |

Self-reported health; self-reported voting in the UK general election (data from National Child Development Study) | Sex, geographic region, age at leaving education, body mass index, chronic illness, and smoking and alcohol consumption frequencies |

| Ballard, Hoyt, & Pachucki (2018) [14] | USA | Association between health and voting | Positive association between civic engagement during late adolescence/early adulthood, and socioeconomic status and mental health in adulthood (decreased risky health behaviors (ES = − 0.12, SE = 0.018, p < 0.001) and fewer depressive symptoms (ES = −0.056, SE = 0.018, p = 0.003) | General health, symptoms, physical limitations, depressions, BMI, physical activity, health risk behaviors; Self-reported voting in the US presidential election (data from National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health) | Demographic characteristics, health variables, social connections |

| Blakely, Kennedy & Kawachi (2001) [6] | USA | Association between health and voting |

Socioeconomic inequality in the US state election voter turnout is associated with poor self-rated health, independent of income inequality and household income. Individuals living in the USA with highest voting inequality had an odds ratio of fair/poor self-rated health of 1.43 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.22, 1.68) compared with individuals living in the USA with lowest voting inequality. |

Self-reported health; self-reported voting in the US State elections (data from Current Population Survey) | Income and state level inequality; age, sex, race, and equivalized household income at individual level |

| Burden et al. (2017) [15] | WI, USA | Association between health and voting |

Positive association between cognitive functioning and voting, and health functioning and voting in older Wisconsin population Better health boosts likelihood of voting by 5% in the 2008 election to 15% in the 2012 election. |

Cognitive functioning, Health Utilities Index (HUI); Catalist voting records for the 2008, 2010, and 2012 US State elections (data from Wisconsin Longitudinal Study) | IQ, age, income, education, gender |

| Couture and Breux (2017) [16] | Canada | Association between health and voting |

Positive association between self-rated health and national electoral participation (statistically significant) Positive association between self-rated mental health and municipal electoral participation (reduction in participation of 9.1% for local elections between the respondents who reported “very good” health and “very bad” health) |

Self-rated health; self-reported voter turnout to Canadian federal and municipal elections (data from Canada General Survey 2013) | Socio-demographic, socio-economic, and social capital data |

| Denny and Doyle (2007) [17] | Ireland | Association between health and voting |

Positive significant association between subjective health and likelihood to vote in the Irish general election: an individual who reports bad health is 6.7% less likely to vote No association between psychological well-being and voter turnout |

Subjective health and mental well-being (WHO-5); 2002 General Ireland election (data from European Social Survey 2005) | Education, sex, age, union membership, political ideology, income, father’s education |

| Denny and Doyle (2007) [18] | Britain | Association between health and voting |

Positive association between voting in the general election and general health and mental health in Britain between 1979–1997 Negative association between smoking and voting Individuals with poor health are 4% less likely to vote in the 1979 and 1997 elections Smokers are 4% less likely to vote in 1979 and 1997 and 3% less likely to vote in the 1987 election compared to non-smokers. |

Self-rated general health, the Malaise Inventory score and indicators of smoking and alcohol consumption; self-reported voter turnout in the 1979, 1987, and 1997 general UK elections | Sex, education, marital status, children, employment, family social class. |

| Habibov and Weaver (2014) [19] | Canada | Association between health and voting |

Positive significant association between social capital and self-rated health in Canada Positive association of voting at all levels and self-rated health in Canada (largest positive effect on self-rated health among all of the social capital variables analyzed) |

Self-rated health; self-reported voting at local, provincial, or federal level of Canadian government (data from Canada General Survey 2008) | Various sociodemographics such as age, sex, marital status, level of education, and income |

| Islam et al. (2006) [20] | Sweden | Association between health and voting |

Positive association between municipal-level social capital (measured as voting) and better health in Sweden A municipality with a voting turnout rate 10% higher (compared to the mean election participation rate) is associated with a 2.4% higher health state score. |

Generic health-related quality of life measure (HRQoL); rates of voting participation in municipal political elections (data from Statistic Sweden’s Survey of Living Condition) | Income, gender, immigration, cohabitation, education, employment, age |

| Islam et al. (2008) [21] | Sweden | Association between health and voting |

Reduced individual risk from all-cause mortality for males 65+ who registered for municipal election participation Higher voting rate negatively and significantly associated with the mortality risk from cancer for males (p = 0.007), and protective associations for cardiovascular mortality (p = 0.134) and deaths due to “other external causes” (p = 0.055) Association did not hold for females. |

Survival time in years and survival status at the end of follow-up period; registered Swedish municipal election participation | Income inequality, initial health status, age, income, education |

| Iversen (2008) [22] | Norway | Association between health and voting |

Positive association of voting in municipal elections and self-assessed health in Norway The association is of considerable magnitude. |

Self-assessed general health and self-assessed mental health; number of votes as a proportion of the number entitled to vote in the Norwegian local elections (data from standard-of-living survey by Statistics Norway and other sources) | Income, education |

| Kim and Kawachi (2006) [23] | USA | Association between health voting |

Positive association between presidential electoral participation and health in the USA Those who had high social trust and electoral political participation had significantly lower odds of fair/poor health (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.52–0.62; and OR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.71–0.86, respectively). |

Self-rated health; self-reported voting in the 1996 presidential election and being currently registered to vote (data from Social Capital Benchmark Study) | Age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and social capital characteristics |

| Kim, Kim, and You (2015) [24] | OECD countries | Association between health and voting |

Significant positive association between voting in the parliamentary election and subjective health controlling for sociodemographic factors Negative association between non-conventional political participation and health |

Self-rated health; self-reported voting in parliamentary elections in 44 OECD countries globally (data from World Value Survey) | Age, sex, marital status, education, and income |

| Lahtinen et al. (2017) [25] | Finland | Association between health and voting |

Results show that health exerts independent effects on voting turnout in the Finnish parliamentary, presidential, and municipal elections. Income partially mediates the effects of social capital on voting. |

Use of healthcare services (including hospitalization data) and medicine purchases; individual-level register the 1999 Finnish parliamentary election and the 2012 presidential and municipal election (data from Statistics Finland) | Income, social class, age, gender, living with a partner, native language, and education |

| Mattila et al. (2013) [26] | Europe | Association between health and voting |

Significant positive association between health and voter turnout in the European parliamentary elections, with effect most notable in older people The difference in voting probability between respondents with very good health and very bad health is 10%. The impact of health is partially mediated by social connectedness. |

Self-rated health; self-reported voting in the last parliamentary election (data from European Social Survey) | One model accounted for age, gender, and education |

| Reitan (2003) [27] | Russia | Association between health and voting |

Positive association between voter turnout in the Russian elections and life expectancy in Russia for both sexes (studied elections from 1991–1999) Overall, correlations were positive and significant. |

Regional data on life expectancy (State Committee of the Russian Federation on Statistic); data on voter turnout collected from the Centre for Russian Studies at the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI) | Unclear |

| Agran, MacLean, and Kitchen (2016) [28] | Western USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Qualitative article focused on lower voting rates in individuals with intellectual disabilities, and barriers and supports needed to support this community Results indicated that people with ID are interested in voting but do not receive education on political issues or voting-related decisions. |

Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Ard et al.(2016) [29] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Significant positive association between engagement in politics (including voting in any US election) and self-rated health in connection to racial health disparities in the USA Social capital mediates racial disparities in health more than industrial air pollution. |

Self-rated health; composite measure of electoral participation which included whether the respondent voted in the past election and is currently registered to vote (data from 2000 Social Capital Benchmark Study). | Age, sex, region of residence, marital status, and educational attainment |

| Bazargan, Kang, and Bazargan (1991) [7] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Positive association of self-rated health and voting in the US presidential election in elderly Caucasian populations: elderly Caucasians who report poor health are 13.1% less likely to vote than those reporting excellent health Positive association of life satisfaction and voting in elderly African American populations |

Self-reported health; self-reported voting turnout from the US presidential election of 1980 | Income, education, age, gender, living arrangement, marital status, club participation, volunteer work, health status, life satisfaction, transportation, fear of crime, union membership, demand on resources, political efficacy, political philosophy |

| Bazargan, Barbe, and Torres-Gil (1992) [8] | New Orleans, USA | Differences in voting associated with health | Positive association between self-rated health and voting for elderly black populations in the US elections: self-reported health status was significantly negatively associated with the number of elections voted in in the bivariate analysis, but not significant in multivariate regression analysis | Self-rated health; self-reported voting in seven elections included presidential, gubernatorial, senatorial, congressional, mayoral elections, and two propositional elections | Age, gender, education, income, accessibility of transportation, church participation, volunteer work, club participation, sense of external efficacy, sense of citizen duty, attention to public affairs, perceived difference between parties, strength of party identification |

| Bergstresser, Brown, and Colesante (2013) [30] | New York City, USA | Differences in voting associated with health | Qualitative study on the power of voting, social recovery, and inclusion for those with mental health issues | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Gollust and Rahn (2015) [31] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Significant negative association between voting and those with heart disease and disabled populations in the 2008 US presidential election Significant positive association between voting, emotional support, and those with cancer |

Self-reporting of chronic health condition, including diabetes, arthritis, angina/coronary heart disease), asthma, and cancer; self-reported voting in the last US presidential election (data from 2009 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey) | Sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, income, education, urbanicity) and health-related confounding factors (health insurance, disability, emotional support) |

| Kawachi et al. (1999) [32] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between female voting rate and female mortality rate: higher political participation was correlated with lower female mortality rates (r = − 0.51) In regression analysis, a one-unit improvement in political participation was associated with 7.3 fewer deaths per 100,000 women (95% confidence interval, CI: 3.8 to 10.9). |

Total female and male mortality rates, female cause-specific death rates and mean days of activity limitations reported by women during the previous month (data from CDC); voter registration (percent women registered to vote in 1992/94), voter turnout (percent women who voted in 1992/94) | Income distribution (using the adjusted Gini coefficients), median income and poverty rates |

| Matsubayashi and Ueda (2014) [33] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between voting in the US presidential election and adults with disabilities compared to population without disabilities The odds of voting in the presidential elections from 1980 to 2008 are 50–60% lower if the respondents have work-preventing disabilities, taking into account socioeconomic factors. |

Self-reported work preventing disabilities; self-reported voting rates (data from Current Population Survey) | Education and income, age, gender, and race and ethnicity |

| Mattila and Papageorgiou (2017) [34] | Europe | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between voting in the European national elections and disability; perception of discrimination increases this trend The probability of a non-disabled person voting is 80%, while the corresponding probability for those with disability and discrimination experiences is 75% (p < 0.01). |

Disability status and disability discrimination; self-reported voting (data from European Social Survey 2012). | Age, gender, education, social connectedness |

| Mino et al. (2011) [35] | New York City, USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between being registered to vote in the US elections (all levels) and drug paraphernalia sharing In bivariate analysis, those registered to vote were less likely to share drug paraphernalia (33% vs. 49%; p = 0.046). This significance decreased in multivariate analysis, where political party identification was associated with lower drug paraphernalia sharing (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.363, CI = 0.155–0.854; p = 0.020). |

Injection drug use health variables (sharing paraphernalia, using shooting galleries) in past 30 days; self-reported voter registration, identifying as political/part of an organized political party and attention paid to politics | All regression models controlled for age, gender, and educational level |

| Ojeda (2015) [36] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between depression and political participation (measured as voting in the US presidential election) Respondents who report no depressed mood have a 0.75 probability of voting, while respondents who report the most severe depressed mood have a probability of voting of < 0.5. |

Self-reported mental health status including Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D); self-reported voter turnout in the 1996 and 2000 US presidential elections (data from 1998 General Social Survey and the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health) | Sex, race, education, age, general health, parental income, education, civic engagement, general health, marital status, church attendance, self-reported happiness (depending on data used) |

| Shields, Schriner, and Schriner (1998) [37] | USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Negative association between voter registration/voting rates in the 1994 US mid-term election and people with disabilities Among non-disabled respondents, 54% reported voting, while 33.1% of the people with disabilities reported voting. |

Self-reported disability causing lack of work participation; self-reported registered and voted, were registered but did not vote, and voted absentee in the 1994 mid-term election (data from 1994 Current Population Survey) | Education, income, age, years of living in the community, and marital status |

| Sund et al. (2017) [38] | Finland | Differences in voting associated with health | Association between chronic diseases and voting in the Finnish parliamentary elections: neurodegenerative brain diseases (dementia OR = 0.20, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.22), alcoholism (OR = 0.66), and mental disorders (depression OR = 0.91; psychotic mental disease OR = 0.79) had a significant negative association, whereas cancer and COPD/asthma had a positive association (both OR = 1.05). Having more than one condition further decreased voting probability (1 condition OR = 0.96, 2 conditions OR = 0.83, 3 conditions OR = 0.68 and 4+ conditions OR = 0.50) | Hospital discharge diagnoses and reimbursements for drugs prescribed, to identify persons with 17 chronic hospital-treated diseases; individual-level register records for the 1999 Finnish parliamentary elections | Gender, age, education, occupational class, income, partnership status, cohabitation with underaged children and hospitalization during election day |

| Urbatsch (2017) [39] | Finland, USA | Differences in voting associated with health |

Association between low voter turnout and influenza outbreaks in USA and Finland In Finland, influenza prevalence reduces turnout in Finnish residential, parliamentary, and municipal elections by 2.1% (95% CI: 21.2 to 23.1 percentage points). In the USA, a higher level of influenza reduces turnout in the US presidential and state elections by 1.2% (95% CI: 20.4 to 22.1). |

Influenza infections; voter turnout is measured as a share of the voting-eligible population at major elections (statistics from the national Finnish and US surveillance systems) | Healthcare access, population > 65, population per square meter, type of election |

| Rodriguez (2018) [40] | USA | Electoral implications |

Positive association between health and political participation causes early mortality of poor people. Health differences between 10-year survivors and non-survivors explain 56% of their differences in socio-political participation. Without detrimental differences in health, individuals would participate 28% more as they age. High-SES survivors participate 60% more than low-SES survivors and 85% more than low-SES non-survivors. |

Mortality status and self-rated health; index of political participation (volunteering, attending meetings, and giving money) (data from Midlife in the United States: a national study of health and well-being) | Education, income |

| Rodriguez et al. (2015) [41] | USA | Electoral implications | Excess mortality in African American populations from 1970 to 2004 (2.7 million deaths) due to health inequality affected 2004 US presidential and state election outcomes (1 million lost black votes) | Deaths by state (data from Multiple Cause of Death files 1970–2004); total number of votes by state (data from US Elections Project, National Election Pool General Election Exit Polls (2004). | Sex, race, age, region |

| Ziegenfuss, Davern and Blewett (2008) [42] | USA | Electoral implications |

Comparison of proportion of those who delayed accessing health care and voted in 2004 compared with the 2000 US national election Those who delay healthcare care were less likely to vote than those who did not in 2000, but not in 2004. In 2004, those who delayed care and voted were more than twice as likely to vote Democratic than Republican. |

Access to healthcare; self-reported voting in the 2000 and 2004 presidential elections (data from American National Election Study) | Age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, marital status, educational attainment, party identification, home ownership, church attendance, and length of time residing in the same home or apartment |

| Anderson and Dabelko-Schoeny (2010) [43] | USA | Healthcare interventions | Commentary on civic engagement leading to better health in nursing home residents from social worker perspective, with call to action for social works to engage | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Hassell and Settle (2017) [44] | USA | Healthcare interventions |

Study experimented with interventions on life stress and likelihood to vote in the US presidential and municipal elections When triggered with life stressors, individuals without a history of voting were significantly less likely to vote while routine voters were unaffected. Non-voters exposed to the life stressors reduced likelihood of voting by 5%. |

Life stressors; self-reported voting in the 2012 US presidential election and the 2013 municipal election in a small Midwestern American town | Used control groups in field experiments |

| Liggett et al. (2014) [45] | Bronx, USA | Healthcare interventions |

Study examined a clinician-led voter registration drive within 2 university-affiliated health centers in the Bronx, New York. 38% of the total patients engaged in voter registration drive were registered to vote for the 2008 US presidential election: 114 of the 304 patients engaged were registered, of which 54% were first-time registrants |

Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Regan, Hudson, and McRory (2011) [46] | USA | Healthcare interventions | Literature review of patient participation in public elections, with call to action for nurses to engage in promoting patients’ right to vote through policy guidelines and a flexible and proactive nursing approach to participation | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Wass et al, (2017) [47] | Europe | Healthcare interventions | Voter facilitation instruments (advance/postal voting, voting outside the polling stations) for parliamentary elections in 30 European countries have insignificant effects to increase electoral participation for those suffering from ill health or disabilities (except proxy voting) | Self-rated disability and self-rated health; self-reported voter turnout (data from European Social Survey) | Gender, age, education and cohabitation with a spouse |

| White and Wyrko (2011) [48] | UK | Healthcare interventions | Commentary encouraging voter outreach in the UK elections to older patients admitted to geriatric rehab hospital | Not applicable | Not applicable |

Four common themes emerged: (1) there are consistent patterns in the association between voting and health; (2) differences in voter participation are associated with health conditions; (3) gaps in voter participation may be related to electoral outcomes; and (4) healthcare interventions exist to increase voting and democratic engagement. We chose these four overarching themes after reviewing summarized notes of the key findings and details of each included article (see Methods). Although there is partial overlap, we believe that articles included under each theme deliver four distinct messages that inform our main research questions in unique ways.

Consistent patterns in the association between voting and health

Seventeen studies examined the association between voting and health in numerous jurisdictions and levels of government (municipal, state or province, and federal elections), and in numerous locations across North America and Europe. Lower voting rates are consistently associated with poor self-rated health. In most studies, health was measured by surveys that included questions about self-reported health [6, 13, 16–19, 22–24, 26]. Other measures included health risk behaviors [12, 14], mortality [21, 27], chronic health conditions [14], health indices [14, 15, 18, 20], and hospitalization data [25]. This health data was then linked to data on voting, measured in various ways including self-reported voting registration and national statistics. Blakely, Kennedy, and Kawachi analyzed the data of 280,000 respondents of an American Current Population Survey and found that voting is positively associated with self-rated health, independent of income inequality [6]. Similar patterns were found by Burden et al. in an older Wisconsin population [15]. Globally, similar correlations between voting and health have been found in Ireland [18], Russia [27], Sweden [20], Canada [16, 19], Europe [26], and the OECD more broadly [24]. Both Couture and Breux [16] and Habibov and Weaver [19] looked at large sample sizes from Canada’s General Social Survey and found a correlation between self-rated health and voting. Habibov and Weaver connected this association between voting and health to the importance of social capital [19], as did many other articles in our review [6, 21–23, 26, 29, 30, 38].

Most studies were cross-sectional, with only a few longitudinal studies finding an association between voting and health and socioeconomic benefits. Adjusting for confounders like sex, education, geography, and chronic illness, Arath showed that voting abstention was associated with 1.3 times higher odds of reporting poor health two years later [13]. Ballard, Hoyt, and Pachucki looked at longitudinal data that followed adolescents into adulthood and found that voting was positively associated with better mental health and health behaviors over time, along with improved income and education level [14].

Differences in voter participation are associated with health conditions

Although the connection between voting and health was researched in the above articles, the next overarching theme further analyzes this connection by discussing voting patterns in distinct sub-populations. People with physical, intellectual, and psychological disabilities have lower rates of voting. Agran, MacLean, and Kitchen found lower voting rates in communities of people with intellectual disabilities [28]. Matsubayashi and Ueda [33], Mattila and Papageorgiou [34], and Shields, Schriner, and Schriner [37] discovered low voter turnout rates among people with disabilities, with barriers to voting including discrimination and accessibility. Mental health and addiction can also impact voting. Mino et al. found a negative association between being registered to vote and harmful drug injection behavior (ex. sharing paraphernalia) [35], and Ojeda found that depression reduced voting participation [36]. In a qualitative study, Bergstresser, Brown, and Colesante interviewed 52 consumers of mental health services who described political participation as contributing to their recovery by increasing social inclusion [30].

There are differences in voter participation by race, gender, age, and disease type. Ard et al. found a positive association between engagement in politics and self-rated health in connection to racial health disparities in the USA [29]. Disparities in health and voting in African American communities were found in two studies by Bazargan, Kang, and Bazargan [7] and Bazargan, Barbre, and Torres-Gil [8], which saw a voting gap in elderly black communities in the USA. Being elderly can lead to certain vulnerabilities, such as social isolation and physical impairment, which can then lead to lower voting rates [26, 43]. Higher political participation (which includes voting participation and registration to vote) in American women is also strongly correlated with lower mortality [32]. Interestingly, the type of disease an individual has can affect their voting behavior. Acute illnesses like influenza can affect voter turnout [39]. Focusing primarily on chronic diseases, Gollust and Rahn found that those with heart disease and disability were less likely to vote in the 2008 US election, whereas those with cancer were more likely to vote [31]. One hypothesis was that strong social support networks in the cancer community, and less stigma compared to other diseases, led to higher voting rates among people with cancer. Sund et al. saw similar results: those with cancer and COPD often voted more, whereas those with neurodegenerative brain disease, addiction, and mental health disorders voted less [38].

Gaps in voter participation may be related to electoral outcomes

Although only three articles were included under this theme, we nonetheless created a distinct category due to the unique and important findings of these articles, namely, differences in health status and subsequent differences in voting patterns can impact electoral outcomes. In two population health studies, Rodriguez [40] and Rodriguez et al. [41] analyzed the association between poor health and voting and the broader impact these inequities can have on our political systems. They hypothesize that “through the early disappearance (i.e., death) of the poor, continuing socio-political participation of high-SES survivors helps to perpetuate inequality in the status quo” [40]. The citizens most expected to vote in line with redistributive health policies are the same citizens that have higher mortality rates during the time when they are most likely to vote—middle age. Previous to this study, Rodriguez et al. looked at how racial inequality in the USA leads to excess mortality and therefore a loss of votes. In introducing the subject of racism and voting, Rodriguez et al. point out current US voter suppression practices aimed at marginalizing minority populations, from felony disenfranchisement laws, to redrawing of electoral boundaries, to shortened polling hours. This article focuses on the effects of health inequity as another threat to minority voting power. They found that from 1970–2004, there were 2.7 million excess black deaths due to racial inequality, which led to 1 million lost black votes in the 2004 election [41]. This study concluded that many close state-level elections in the US over this period of time would likely have had different electoral outcomes if not for these excess mortality rates.

Using a multivariate analysis and controlling for sociodemographic characteristics, Ziegenfuss, Davern, and Blewett [42] found that individuals with healthcare access problems were significantly more likely to vote for Democratic candidates in the 2004 election. They connected this to the Democratic Party comprehensive approach to healthcare reform in the 2004 election. If inequities in access to healthcare services and in health outcomes can change who wins elections, a vicious cycle can emerge: worse health leads to lower voting rates, leading to policy that does not prioritize addressing inequities, leading to worsening health inequities.

Healthcare interventions exist to increase voting and democratic engagement

Healthcare interventions aimed at increasing voting rates have emerged within nursing, social work, and medicine. Regan, Hudson, and McRory conducted a literature review that looked at the role of nurses in ensuring patients’ right to vote, issuing a call to action for nurses to help ensure this right through policy guidelines and increased support for patients [46]. Anderson and Dabelko-Schoeny argued that civic engagement can lead to better health in nursing home residents and called for social workers to develop and implement interventions that increase engagement [43]. White and Wyrko wrote that healthcare professionals should make every effort to ensure hospital patients can vote in the UK [48]. They suggest an approach focused on increased awareness and discussion among healthcare practitioners, promotion of voting access, and the consideration of emergency proxy voting.

Within the healthcare setting, Wass et al. found that proxy voting as a voter facilitator instrument can increase voter turnout for those suffering from ill health or disability [47]. Hassell and Settle ran an interventional study that induced life stressors on patients and found that increasing stress decreased likelihood to vote for typical non-voters [44]. Liggett et al. conducted an evaluation of clinician-led, nonpartisan voter registration drives over 12 weeks within two university-affiliated health centers in the Bronx, New York [45]. The project was successful in registering 89% of eligible voters, demonstrating the importance of health centers as, “powerful vehicles for bringing a voice to civically disenfranchised communities”.

Discussion

Our review found an association between voting and health. Poor health is often associated with lower rates of voting. This was consistent across diverse health outcomes, jurisdictions and governments. A few studies provided weak evidence that voting may lead to better health and well-being [13, 14], although there have not been enough studies in this area to strongly confirm this association. Individuals living with disability, mental and physical illness, minorities, and older individuals, tend to vote at lower rates in general. Votes lost to morbidity and mortality in marginalized populations may potentially impact electoral and policy outcomes, including public health policy. Among some of the included studies, the causal relationship between voting and health was seen as bidirectional: voting affects health as it shapes who is in power and what policy is made, and individual health can affect voting. Taken together, a cycle can develop of poor health and political disempowerment, although further research is required to fully characterize this process. Despite the importance of this relationship, the association between voting and health has not received significant attention in the public health literature to date [49]. This review provides some conceptual clarity to this developing research area.

Many articles included calls to action for healthcare practitioners to engage in and advocate for democratic engagement in their patient communities through policy change, accessibility, support, and even intervention to help increase voter participation. Healthcare organizations are well suited to engage directly with marginalized populations and can be involved in improving democratic engagement through education and interventions similar to Liggett et al., who undertook a clinician-led voter registration [45]. Other possible interventions could include reducing barriers to voting (proxy voting at hospitals), organizing nonpartisan townhalls, or compiling and sharing information for communities on the voting process [50, 51].

Many authors proposed theories to explain why poor health and lower voting turnout were associated. These included that people with poor health had lower cognitive resources, worse sense of efficacy, unmet accessibility needs (especially for those with disabilities), and limitations in time, social/emotional, and financial resources due to health burden [25, 29, 31]. Several authors cited social capital and social connectedness as part of the causal link between voting and health. Voting could be seen as a form of social capital as it entails social trust and civic engagement, but even more than that, having social networks who vote and talk about voting can reinforce voting patterns within a community. Social connectedness can improve mental and physical health, lead to less risky health behaviors, and increase access to community networks, institutions, and resources to improve health [16, 20–22]. Gollust and Rahn explored the role social capital played in voting and health by discussing one of the only populations where voting rates increase with a chronic health condition: people living with cancer [31]. They hypothesized that people living with cancer are much more likely to join social and advocacy cancer support groups than people with other diseases. For example, people with breast cancer form more than forty times more support groups than people with heart disease. These social and advocacy groups not only then support the act of voting, but also equip members with skills that help them better understand the political process, which then leads to higher voter participation. Overall, many authors linked voting to health through social capital. This is an important area of future research for the field of public health, as social capital is a key social determinant of health in itself [3]. This links back to an important consideration in our scoping review: how voting is connected to the social determinants of health.

Our review had limitations. Voting was chosen as a proxy for democratic engagement, but there are numerous other forms of democratic engagement: activism, protest, donations to political groups, political education, and more. Also, democracy comes in many forms, between countries and within countries at different times. We recognize this would influence how voting occurs in different contexts, the meaning it would have to citizens, and the subsequent relationship between voting and health. Voting is also deeply connected with other social determinants of health—namely income and education—which may confound some of the research presented. Most of the articles addressed confounders within their statistical analysis, including sex, age, marital status, race, education, employment, income, geography, and more. Addressing these confounders was imperative in claiming an association between voting and health, but it is important to note that the articles often measured these factors differently and used a differing combination of factors. Future work should synthesize this literature to develop a more holistic picture of the connection between other forms of democratic engagement and health. Future research should also examine the long-term effects of voting on health, as well as the impact of health organizations actively intervening in and advocating for democratic engagement in their communities.

Conclusion

This review has supported the association between voting and health. Communities marginalized by disability, mental and physical health, race, and age tend to be the most affected by the positive association between health and voting. Differences in voter participation related to health inequities can have some effect on overall electoral outcomes, shaping overall policy and possibly deepening healthcare inequities. Future research should study the long-term effects of voting on health, the effects of other forms of democratic engagement on health, and the impact healthcare practitioners can have on voting activity in their community through intervention and advocacy.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: MEDLINE search strategy.

Additional file 2: Articles identified by database.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support of Teruko Kishibe, an information specialist at the Health Sciences Library, St. Michael’s Hospital. We would like to thank Elina Farmanova and Ross Upshur for their comments and review of this article.

Authors’ contributions

CB, DR, and AP participated in conceiving and designing the study. CB and DR conducted the database searches. CB reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles for the initial article screen. CB and DR reviewed the full text of included articles and extracted and summarized information. CB drafted the manuscript. CB, DR, and AP contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Andrew D. Pinto is supported as a Clinician Scientist by the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine at the University of Toronto, by the Department of Family and Community Medicine, St. Michael’s Hospital, and by the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael’s Hospital. Dr. Pinto is also supported by a fellowship from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation and as the Associate Director for Clinical Research at the University of Toronto Practice-Based Research Network (UTOPIAN). The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from any institution or funding source.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s40985-020-00133-6.

References

- 1.Lucyk K, McLaren L. Taking stock of the social determinants of health: a scoping review. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0177306. 10.1371/journal.pone.0177306. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0177306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Final Report of the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- 3.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Soc Determ Heal Discuss Pap 2 (Policy Pract [Internet]). 2010;79. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44489/1/9789241500852_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1.

- 4.Sanders D, Fisher SD, Heath A, Sobolewska M. The democratic engagement of Britain’s ethnic minorities. Ethn Racial Stud. 2014;37(1):120–139. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Democratic engagement: a report of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing (CIW). Canadian Index of Wellbeing, 2010. Available at: https://uwaterloo.ca/canadian-index-wellbeing/sites/ca.canadian-index-wellbeing/files/uploads/files/DemocraticEngagement_DomainReport_0_0.pdf.

- 6.Blakely TA, Kennedy BP, Kawachi I. Socioeconomic inequality in voting participation and self-rated health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):99–104. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bazargan M, Kang TS, Bazargan S. A multivariate comparison of elderly African Americans’ and Caucasians’ voting behavior: How do social, health, psychological, and political variables affect their voting? Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1991;32(3):181–98. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2190/49TT-9AFR-UX2G-PGFU. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bazargan M, Barbre AR, Torres-Gil F. Voting behavior among low-income black elderly: a multielection perspective. Gerontologist. 1992;32(5):584–591. doi: 10.1093/geront/32.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mackenbach JP. Political determinants of health. Eur J Pub Health. 2013;24(1):2. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O’Brien KK, Straus S, Tricco AC, Perrier L, et al. Scoping reviews: time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albright K, Hood N, Ma M, Levinson AH. Smoking and (not) voting: the negative relationship between a health-risk behavior and political participation in Colorado. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(3):371–376. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arah OA. Effect of voting abstention and life course socioeconomic position on self-reported health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(8):759-60. 10.1136/jech.2007.071100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Ballard PJ, Hoyt LT, Pachucki MC. Impacts of adolescent and young adult civic engagement on health and socioeconomic status in adulthood. Child Dev 2018;00(0):1–17. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/cdev.12998. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Burden BC, Fletcher JM, Herd P, Jones BM, Moynihan DP. How different forms of health matter to political participation. J Polit. 2017;79(1):166–178. doi: 10.1086/687536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couture J, Breux S. The effects of political participation on political efficacy. Eur J Pub Health. 2017;27(4):599–604. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denny KJ, Doyle OM. Analysing the relationship between voter turnout and health in Ireland. Ir Med J. 2007;100(7):55–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denny KJ, Doyle OM. “...Take up thy bed, and vote” Measuring the relationship between voting behaviour and indicators of health. Eur J Pub Health. 2007;17(4):400–401. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Habibov N, Weaver R. Endogenous social capital and self-rated health: results from Canada’s General Social Survey. Health Sociol Rev. 2014;23(3):219–231. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Islam MK, Merlo J, Kawachi I, Lindström M, Burström K, Gerdtham U-G. Does it really matter where you live? A panel data multilevel analysis of Swedish municipality-level social capital on individual health-related quality of life. Heal Econ Policy Law. 2006;1(03):209. doi: 10.1017/S174413310600301X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Islam MK, Gerdtham UG, Gullberg B, Lindström M, Merlo J. Social capital externalities and mortality in Sweden. Econ Hum Biol. 2008;6(1):19–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iversen T. An exploratory study of associations between social capital and self-assessed health in Norway. Heal Econ Policy Law. 2008;3(4):349–364. doi: 10.1017/S1744133108004544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D, Kawachi I. A multilevel analysis of key forms of community- and individual-level social capital as predictors of self-rated health in the United States. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):813–826. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9082-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim S, Kim CY, You MS. Civic participation and self-rated health: a cross-national multi-level analysis using the world value survey. J Prev Med Public Health. 2015;48(1):18–27. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.14.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lahtinen H, Mattila M, Wass H, Martikainen P. Explaining social class inequality in voter turnout: the contribution of income and health. Scand Polit Stud. 2017;40(4):388–410. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mattila M, Söderlund P, Wass H, Rapeli L. Healthy voting: the effect of self-reported health on turnout in 30 countries. Elect Stud. 2013;32(4):886–891. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reitan TC. Too sick to vote? Public health and voter turnout in Russia during the 1990s. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2003;36(1):49–68. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agran M, MacLean WE, Kitchen KAA. “My voice counts, too”: voting participation among individuals with intellectual disability. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2016;54(4):285–294. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-54.4.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ard K, Colen C, Becerra M, Velez T. Two mechanisms: the role of social capital and industrial pollution exposure in explaining racial disparities in self-rated health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bergstresser SM, Brown IS, Colesante A. Political engagement as an element of social recovery: a qualitative study. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(8):819–821. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.004142012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gollust SE, Rahn WM. The bodies politic: chronic health conditions and voter turnout in the 2008 election. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2015;40:1115–55 Available from: http://jhppl.dukejournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1215/03616878-3424450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Kawachi I, Kennedy BP, Gupta V, Prothrow-Stith D. Women’s status and the health of women and men: a view from the States. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsubayashi T, Ueda M. Disability and voting. Disabil Health J. 2014;7(3):285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mattila M, Papageorgiou A. Disability, perceived discrimination and political participation. Int Polit Sci Rev. 2017;38(5):505–519. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mino M, Deren S, Kang SY, Guarino H. Associations between political/civic participation and HIV drug injection risk. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2011;37(6):520–524. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2011.600384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojeda C. Depression and political participation. Soc Sci Q. 2015;6(5):1226–1243. doi: 10.1111/ssqu.12173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shields TG, Schriner KF, Schriner K. The disability voice in American politics: political participation of people with disabilities in the 1994 election. J Disabil Policy Stud. 1998;9(2):33–52. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sund R, Lahtinen H, Wass H, Mattila M, Martikainen P. How voter turnout varies between different chronic conditions? A population-based register study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(5):475–479. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-208314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urbatsch R. Influenza and voter turnout. Scand Polit Stud. 2017;40(1):107–119. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodriguez JM. Health disparities, politics, and the maintenance of the status quo: a new theory of inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2018;200(January):36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez JM, Geronimus AT, Bound J, Dorling D. Black lives matter: differential mortality and the racial composition of the U.S. electorate, 1970–2004. Soc Sci Med. 2015;136–137:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ziegenfuss JK, Davern M, Blewett LA. Access to health care and voting behavior in the United States. J Heal Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):731–742. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson KA, Dabelko-Schoeny HI. Civic engagement for nursing home residents: a call for social work action. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2010;53(3):270–282. doi: 10.1080/01634371003648323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hassell HJG, Settle JE. The differential effects of stress on voter turnout. Polit Psychol. 2017;38(3):533–550. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liggett A, Sharma M, Nakamura Y, Villar R, Selwyn P. Results of a voter registration project at 2 family medicine residency clinics in the Bronx, New York. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(5):466–469. doi: 10.1370/afm.1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regan P, Hudson N, McRory B. Patient participation in public elections: a literature review. Nurs Manag (Harrow) 2011;17(10):32–36. doi: 10.7748/nm2011.03.17.10.32.c8358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wass H, Mattila M, Rapeli L, Söderlund P. Voting while ailing? The effect of voter facilitation instruments on health-related differences in turnout. J Elections Public Opin Parties. 2017;27(4):503–522. [Google Scholar]

- 48.White C, Wyrko Z. Enabling voting for inpatients at geriatric rehabilitation hospitals. GM. 2011;41(6):338-9. Available at: https://www.gmjournal.co.uk/media/21817/gmjun2011p338.pdf.

- 49.Gagné T, Schoon I, Sacker A. Health and voting over the course of adulthood: evidence from two British birth cohorts. SSM - Popul Heal. 2020;10(December 2019):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gruen RL, Pearson SD, Brennan TA. Physician-citizens—public roles and professional obligations. JAMA. 2004;291(1):94–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Exworthy M, Morcillo V. Primary care doctors’ understandings of and strategies to tackle health inequalities: a qualitative study. Prim Heal Care Res Dev. 2019;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: MEDLINE search strategy.

Additional file 2: Articles identified by database.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable