Abstract

Steroid hormone receptors (SRs) are classically defined as ligand-activated transcription factors that function as master regulators of gene programs important for a wide range of processes governing adult physiology, development, and cell or tissue homeostasis. A second function of SRs includes the ability to activate cytoplasmic signaling pathways. Estrogen (ER), androgen (AR), and progesterone (PR) receptors bind directly to membrane-associated signaling molecules including mitogenic protein kinases (i.e. c-Src, AKT), G-proteins, and ion channels to mediate context-dependent actions via rapid activation of downstream signaling pathways. In addition to making direct contact with diverse signaling molecules, SRs are further fully integrated with signaling pathways by virtue of their N-terminal phosphorylation sites that act as regulatory hot-spots capable of sensing the signaling milieu. In particular, ER, AR, PR, and closely related glucocorticoid receptors (GR) share the property of accepting (i.e. sensing) ligand-independent phosphorylation events by proline-directed kinases in the MAPK and CDK families. These signaling inputs act as a “second ligand” that dramatically impacts cell fate. In the face of drugs that reliably target SR ligand-binding domains to block uncontrolled cancer growth, ligand-independent post-translational modifications guide changes in cell fate that confer increased survival, EMT, migration/invasion, stemness properties, and therapy resistance of non-proliferating SR+ cancer cell subpopulations. The focus of this review is on MAPK pathways in the regulation of SR+ cancer cell fate. MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of PR (Ser294) and GR (Ser134) will primarily be discussed in light of the need to target changes in breast cancer cell fate as part of modernized combination therapies.

INTRODUCTION

Of the 48 ligand-activated and “orphan” (i.e. ligands remain unidentified) nuclear receptors (NRs), 6 are related members of the SR superfamily whose steroid hormone ligands are primarily derived from cholesterol metabolism; estrogen receptor (ERα, ERβ), progesterone receptor (PR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), androgen receptor (AR) and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). PGR is most well-studied as an estrogen-responsive gene and PR expression is used as a clinical biomarker of intact estrogen signaling or functional ER. There are two predominant PR isoforms: full-length PR-B and N-terminally truncated PR-A that is missing the first 164 amino acids found in full-length PR-B, termed the B-upstream segment (BUS). Although PR-A and PR-B share structural and sequence identity downstream of the BUS, this segment contains regulatory components that account for major differences in PR-binding partners, promoter selectivity, and transcriptional activity between these two isoforms. A third uterus-specific isoform, termed PR-C, is a further truncated PR receptor composed of only the hinge region and hormone binding domain (HBD) that is incapable of binding DNA but inhibits PR transactivation. PR-C signaling occurs specifically in the fundal myometrium during the onset of labor, and is likely mediated by direct competition for C-terminal binding partners (Condon et al, 2006). PR-A and PR-B are generally co-expressed in PR+ tissues such as the breast or uterus, but are not always found together in the same cells (Aupperlee et al, 2005). Along with ER and Her2, total PR levels, rather than individual PR isoforms, are measured clinically to classify the luminal A (ER+/PR+) and luminal B (ER+/PR-low/null) breast cancer subtypes. However, increasing studies have implicated differential PR isoform expression in the etiology of breast cancer (Lamb et al, 2018; Mote et al, 2002; Mote et al, 2015; Rojas et al, 2017). Furthermore, PRs dramatically influence ER transcriptional responses (Daniel et al, 2015; Mohammed et al, 2015; Singhal et al, 2018); PR-A can transrepress both ER and PR-B (Abdel-Hafiz et al, 2002), while PR-B is an important ER-binding partner (Daniel et al, 2015; Mohammed et al, 2015). Measuring PR isoform ratios by immunohistochemistry (IHC) has been reported (Sletten et al, 2019) but remains challenging due to the lack of reliable antibodies that are capable of accurately distinguishing PR-A versus PR-B since there are no unique amino acid sequences in PR-A. Thus, defining the context-dependent actions of PR isoforms is crucial to understanding how imbalanced PR-A/PR-B ratios can be exploited therapeutically in the clinic.

Closely related to PR within the SR superfamily, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor responsible for integrating the physiologic, pathological, and therapeutic functions of hormonal (cortisol, endogenous corticosteroids) and synthetic glucocorticoids like dexamethasone. GR is ubiquitously expressed and drives the expression of glucocorticoid-responsive genes in a cell/tissue- and promoter-specific manner after glucocorticoid binding to the GR C-terminal ligand binding pocket (Kumar & Thompson, 2019; Miranda et al, 2013). Consequently, GR activation regulates diverse gene programs controlling metabolism, immune system and central nervous system function to maintain cellular homeostasis. Like other steroid hormone receptors, GR consists of three functional domains: intrinsically disordered N-terminal (NTD), DNA-binding (DBD), and ligand-binding (LBD). NTD and LBD contain transcription Activation Function regions, AF1 and AF2, respectively (Kumar & Thompson, 2005). AF2 is strictly ligand-dependent, while AF1 can act constitutively in the absence of the LBD (Oakley & Cidlowski, 2013), a property shared by both PR (Goswami et al, 2014) and AR (Dehm et al, 2008). Like other SRs, functionally distinct AF domains of GR mediate transcriptional activation by recruiting coregulatory complexes that remodel chromatin, target initiation sites, and stabilize RNA polymerase II for gene transcription (Miranda et al, 2013). Similar to PR isoform structure, a further complexity of GR action is that a large cohort of GR isoforms can be created form a single gene (known as NRC31) by alternate splicing and at least eight alternative translational start sites within the GR N-terminal domain sequence (Duma et al, 2006; Presul et al, 2007; Turner & Muller, 2005). The multiple GR isoforms are expressed in a highly tissue-specific manner and, when expressed as individual isoforms experimentally, GR isoforms regulate remarkably distinct transcriptomes (Lu & Cidlowski, 2005).

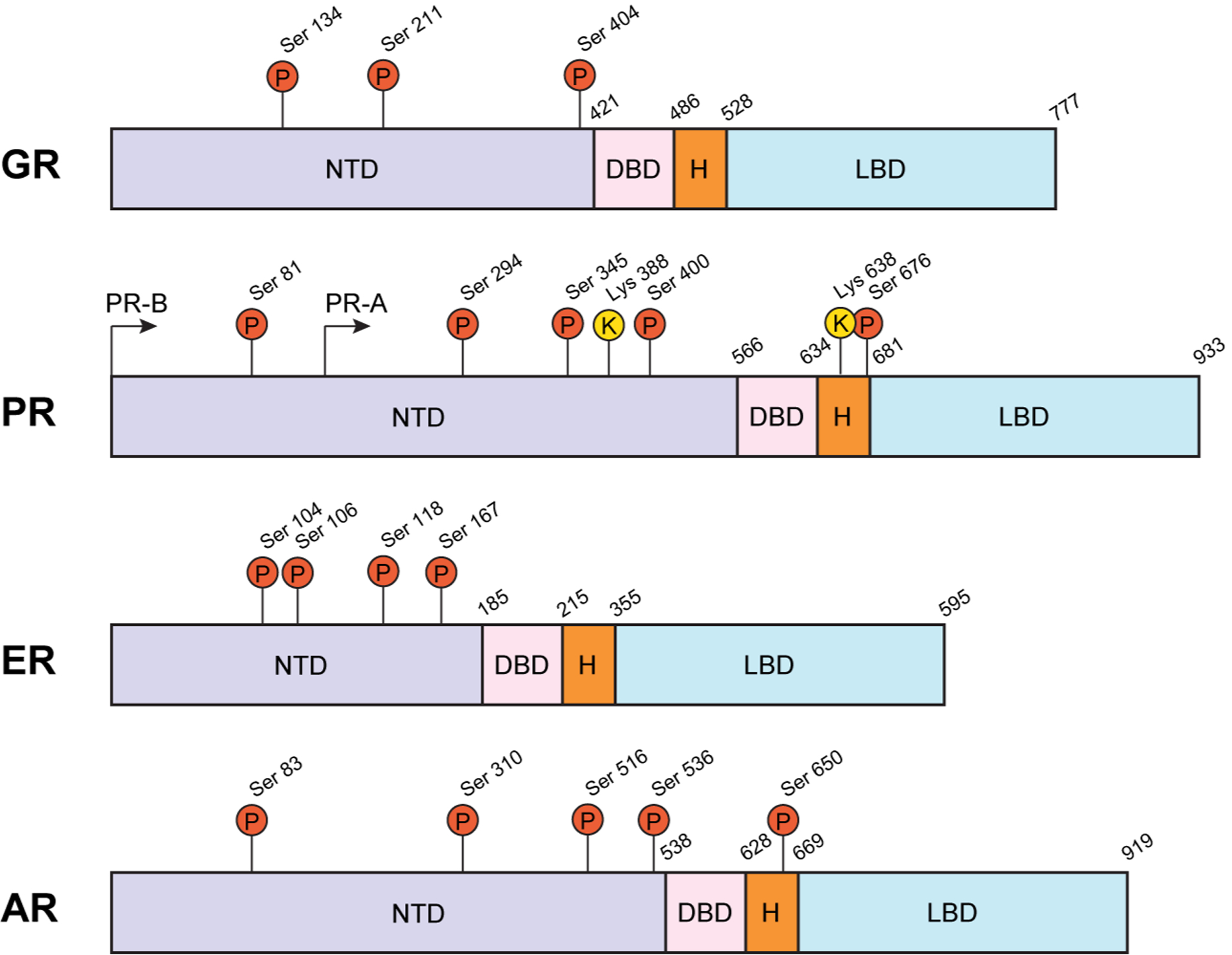

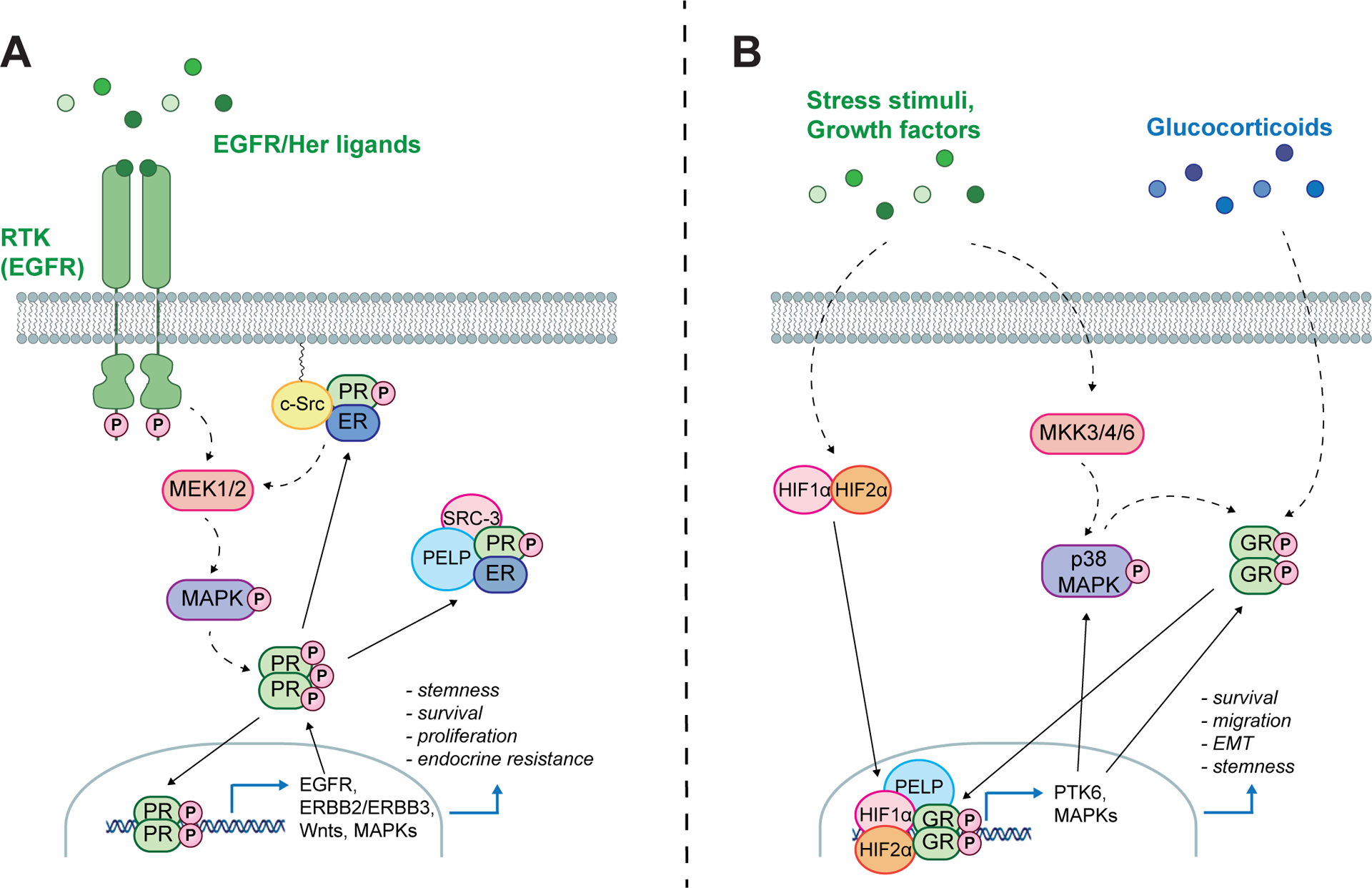

Within the NTD of all SRs, serine, threonine and lysine residues can be post-translationally modified (Figure 1). Our prior studies have primarily defined MAPK-dependent phospho-PR transcriptomes (Knutson et al, 2012; Knutson et al, 2017). While the extent to which phosphorylation events modify the GR cistrome is still being studied, such modifications significantly alter GR function (Galliher-Beckley et al, 2011). For example, recent collaborative studies from our group (Regan Anderson et al, 2018; Regan Anderson et al, 2016) have established GR as an important sensor of both life stress (i.e. a collection of classical GR ligands acting via the LBD) as well as inducible cellular (hypoxia, reactive oxygen species (ROS), nutrient starvation) and microenvironmental (cytokine) stress, largely acting via p38 MAPK-dependent phosphorylation of Ser134 (Figure 2). Herein, we review the regulation of PR and GR by members of the MAPK family and highlight the functional redundancy of these closely related SRs as key mediators of advanced luminal (PR) and triple negative (GR) breast cancer phenotypes and therapy resistant tumor progression. A major consequence of the integration of SR actions with MAPK signaling pathways is the establishment of potent feed-forward signaling loops capable of driving persistent, ligand-independent SR activation needed for sustained biological responses relevant to breast cancer cell autonomy and metastatic dissemination.

Figure 1. Post-translational modifications to steroid receptors.

Multiple posttranslational modification sites are present in the N-terminal domain (NTD) of GR, PR, ER, and AR. PR and AR also have a serine phosphorylation site in the hinge (H) region. The annotated pro-directed sites are known to be modified by MAPKs and/or CDKs and alter SR transcriptional activity and co-factor binding. DNA-binding and ligand-binding domains are also indicated.

Figure 2. Phosphorylation of PR and GR establishes a feed-forward signaling paradigm.

Phosphorylation of PR Ser294 by p42/p44 MAPKs (A) and GR Ser134 by stress-activated p38 MAPKs (B) modulates SR target gene selection to drive expression of genes that are able to further promote SR phosphorylation. This establishes a feed-forward signaling loop in the absence of steroid ligand resulting in cell survival, migration, EMT and non-proliferative/stem cell states.

STUDIES of SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION:

MAPK signaling pathways promote ligand-independent actions of phospho-SRs

Reversible post-translational modifications (PTMs) of SRs include phosphorylation, SUMOylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination. These PTMs may account for the functional diversity of receptor isoforms. This section will primarily focus on ligand-independent actions of PR and GR; the hormonal regulation of these SRs in breast cancer models have been reviewed (Diep et al, 2015; Scheschowitsch et al, 2017; Truong & Lange, 2018). Ligand-independent SR activation has been proposed as a contributing factor to the gradual loss of hormone responsiveness in which SRs shift to hormone-independent or resistant states; this process is well-studied with regard to ER, while a similar paradigm is emerging for both PR and GR (Arpino et al, 2008; Giulianelli et al, 2008; Irusen et al, 2002; Matthews et al, 2004; Shen et al, 2001). One mechanism by which SRs become less dependent upon natural ligands occurs through hormone-induced rapid activation of cytoplasmic signaling pathways that in turn, phosphorylate and sustain SR activation in diminishing ligand (Figure 2). For example, constitutive ER/PR complexes exist in breast cancer cell lines and primary breast tumors (Daniel et al, 2015); trace levels of either estrogen (E2) or progestin (P4) induce rapid (3–15 mins) activation of p42/p44 MAPKs (ERK1/2) via cytoplasmic or membrane-associated ER/PR/c-Src complexes that have been shown to regulate breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro (Ballare et al, 2003; Boonyaratanakornkit et al, 2001; Migliaccio et al, 1998).

We and others have shown that the SR coactivator, PELP1, functions as a cytoplasmic scaffold for docking of multiple SRs including GR (Kayahara et al, 2008; Regan Anderson et al, 2016), AR (Yang et al, 2012) and both ER and PR (Truong et al, 2018; Vadlamudi et al, 2001) as well as the SR coactivator, SRC-3 (Truong et al, 2018). Indeed, a common link between GR signaling in TNBC (discussed below) and PR signaling in ER+ luminal breast cancer is the functional role of PELP1 as a scaffold to bring cytoplasmic kinases and SRs into close proximity. In TNBC models, PELP1 expression is upregulated in response to chemotherapy and cellular stress including hypoxia and ROS production. PELP1 and GR interactions increase in response to the glucocorticoid dexamethasone and creation of ROS by hydrogen peroxide (Regan Anderson et al, 2016). Furthermore, a transcriptional complex containing PELP1, GR and hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) is recruited to the breast tumor kinase (Brk/PTK6) promoter; stress-induced Brk/PTK6 signaling promotes breast cancer cell survival, migration, and metastasis (Castro & Lange, 2010; Lofgren et al, 2011; Regan Anderson et al, 2013). Similarly, in ER+ breast cancer, PELP1 scaffolds SRC-3, ER, and PR to promote ER phosphorylation (i.e. at Ser118 and Ser167) and expression of E2-induced genes involved in cell survival and stem/progenitor cell formation (Truong et al, 2018). Notably, expression of PR-B (but not progesterone) was required for E2-induced expression of a distinct ER/PR target gene signature that predicts greatly shortened survival in luminal breast cancer patients (Daniel et al, 2015). Treatment of breast cancer cells with SI-2, an SRC-3 inhibitor, disrupts ER/PR/PELP1 complexes and blocks PELP1-induced tumorsphere formation. Importantly, the PELP1/GR interaction is enhanced by GR Ser134 phosphorylation, while PR Ser294 phosphorylation is required for the PELP1/PR/ER interaction. Thus, SRs participate in cytoplasmic signaling complexes that enable them to rapidly sense changes in the signaling microenvironment through direct PTMs. All SRs can be phosphorylated at multiple proline-directed sites within the NTD, and PR and AR also contain these sites in the hinge region (Figure 1). Specifically, upregulation of MAPK-associated signaling pathways (e.g. Akt, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK) in cancer states can lead to ligand-independent activation of SRs via phosphorylation at their N-terminal phosphorylation sites (Figure 1). Ligand-independent phosphorylation at Ser118 (via MAPK) or Ser167 (via Akt) are two of the most well-studied phosphorylation sites in ER (Stellato et al, 2016). Additionally, PR (Ser294, Ser 345, Ser400) and GR (Ser134) also undergo ligand-independent phosphorylation in response to growth factor or cytokine induced activation of cytoplasmic kinase (MAPKs, CDKs) pathways. As discussed below, these signaling inputs to SR N-termini phospho-sites can dramatically impact cell fate decisions that are highly relevant to breast cancer progression.

Mitogenic signaling inputs to PR phosphorylation and transcriptional activity

PR transcriptional activity and promoter selection are dramatically influenced by activation of mitogenic and cell cycle-dependent protein kinases (i.e. MAPK, Akt, CK2, and cylin-dependent kinases [CDK]) that alter PR phosphorylation (Daniel et al, 2007; Dressing et al, 2014; Faivre et al, 2008; Hagan et al, 2011; Knotts et al, 2001; Pierson-Mullany & Lange, 2004; Zhang et al, 1997), SUMOylation (Daniel et al, 2007; Daniel & Lange, 2009), or acetylation (Daniel et al, 2010). Modification of SRs may not appreciably alter transcriptional activity as measured using reporter gene assays in vitro, but is a major mechanism for regulating endogenous target gene selection. PTM sites identified on PR that are known to alter its transcriptional activity at selected endogenous target genes include phosphorylation (S81 unique to PR-B, S294, S345, and S400), SUMOylation (K388), and acetylation (K183, K638, K640, and K641). These PTMs enable PR to induce diverse biological outcomes such as anchorage-independent growth/survival, tumorsphere formation as a readout of stemness properties, and cell cycle-dependent gene regulation. These biologies are context-dependent as determined by the presence/absence of activated signaling pathways and the availability of coregulators.

For example, PR Ser294 phosphorylation is ligand-induced (progestins), but also occurs through ligand-independent pathways in response to tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor-induced MAPK and/or CDK activation. Phospho-Ser294 PR-B species are deSUMOylated at Lys388 and are subject to more rapid ligand-dependent receptor downregulation relative to dephosphorylated and heavily SUMOylated PR species (Daniel et al, 2007). Lys388 SUMOylation is a transcriptionally repressive modification at PR target genes associated with cancer biology that also stabilizes PRs in the presence of progestin by slowing their 26S proteasome/ubiquitinoylation-dependent degradation. However, a number of genes (i.e. including numerous tumor suppressor genes) are induced by SUMOylated PRs. Co-mutation of PR-B Lys388 (K388R) rescues transcriptional deficiencies of phospho-mutant PR-B S294A receptors in luciferase assays (Daniel et al, 2007). Interestingly, studies with SUMO-deficient mutant PR-B (K388R; a biochemical phospho-mimic) demonstrated that SUMO-deficient PR-B exhibited transcriptional hyperactivity at a unique subset of PR target genes crucial for cell cycle regulation, proliferation, and survival. This occurred independently of progestins, and was increased by activated CDK2 (Daniel & Lange, 2009). Additionally, breast cancer cell models expressing K388R PR exhibited an alternative gene program significantly associated with Her2 signaling in luminal B (HER2+) breast cancers and the emergence of endocrine resistance (Knutson et al, 2012). These studies suggest that in breast cancer cells with increased MAPK or CDK2 signaling, phospho-Ser294 PR-B (i.e. SUMO-deficient) species promote the expression of transcriptional programs that can contribute to tumor heterogeneity (e.g. emergence of HER2+ cells) during luminal tumor progression (Knutson et al, 2012). Crosstalk between Ser294 and Lys388 in PR-A was less apparent relative to that in PR-B (Daniel et al, 2007). Additional studies are ongoing to define the isoform-specific contributions of SUMO-deficient (i.e. K388R mutant) and Ser294-phosphorylated PR-A.

Recently, PRs have been implicated in mechanisms of early luminal breast cancer dissemination; progesterone induced migration of mammary cells from early lesion, but not primary tumor samples from BALB-NeuT mice (Hosseini et al, 2016). Breast tumor cells co-associate with local and circulating carcinoma-associated fibroblasts (c-CAFs) that can be detected as cancer stem cell/c-CAF cell co-clusters in both mouse models of breast cancer and the blood of patients with metastatic disease (Ao et al, 2015). Related to these studies, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF-2), produced by CAFs, has been shown to activate PR in breast cancer models (Giulianelli et al, 2008). This ultimately leads to transcription of known PR target genes MYC and CCND1, resulting in increased hormone-independent cell proliferation in mouse mammary tumor models. Follow-up studies further defined that FGF-2 promotes interaction between ER and PR at the MYC enhancer and proximal promoter regions (Giulianelli et al, 2019). Notably, over 700 canonical proteins were recruited to MYC regulatory sequences following FGF-2 induction, which included both PR isoforms (PR-A and PR-B) as well as the expression of a novel PR splice variant protein product PR-BΔ4. These studies suggest that the PR-BΔ4 variant, which has an impaired ligand binding domain and lacks the nuclear localization signal, may play a significant role in ligand-independent PR actions, given that it is induced and activated by FGF-2 but not progestins. The inclusion of non-canonical PR isoforms such as PR-BΔ4 in studies of ER+ breast cancer may reveal alternate avenues to prevent or treat endocrine resistance and effectively block luminal breast cancer progression and metastasis. Namely, CAF-derived FGF-2 represents a potent second ligand that is sensed by PRs in order to sustain ligand-independent PR activation in disseminated cancer cell/CAF clusters, and reveals a novel strategy to target phospho-PR actions in otherwise hormone-ablated breast cancer patients.

Stress signaling inputs to GR phosphorylation and transcriptional activity

Glucocorticoids (i.e. corticosteroid GR agonists) are one of the most commonly prescribed and effective treatment regimens for acute inflammatory conditions as well as many chronic inflammatory diseases. However, some patients become unresponsive to these treatments due to the development of glucocorticoid resistance. One of the mechanisms that accounts for this resistance is decreased glucocorticoid signaling, which is correlated with changes in GR phosphorylation (Bloom, 2004; Tsitoura & Rothman, 2004). GR phosphorylation by ubiquitous protein kinases has been shown to lead to altered GR transcriptional activity and interaction with other coregulatory proteins (Galliher-Beckley et al, 2011; Krstic et al, 1997). GR is phosphorylated on serine residues Ser113, Ser134, Ser141, Ser203, Ser211 and Ser226 by cyclin-dependent kinases, MAPK and casein kinase II (Ismaili & Garabedian, 2004) (Figure 1). Three of these GR residues (Ser204, Ser211 and Ser226) are located within the AF1 domain, while the remainder are found in the NTD (Ismaili & Garabedian, 2004; Mason & Housley, 1993).

Phosphorylation of Ser134 by p38 MAPK is the most well-studied GR PTM event. Ligand-independent phosphorylation of Ser134 in response to stress-activating stimuli requires p38 MAPK in U2OS osteosarcoma cells (Galliher-Beckley et al, 2011) and TNBC models (Regan Anderson et al, 2016). In TNBC cells, p38 MAPK inhibition blocked Ser134 GR phosphorylation and abrogated the ability of GR to associate with a GRE-containing region of the BRK (breast tumor kinase) promoter (Regan Anderson et al, 2016). Ligand-independent regulation of GR transcriptional activity is further supported by studies showing p38 MAPK-induced phosphorylation of Ser134 increased the association of GR with the 14–3-3zeta signaling proteins on gene regulatory regions in chromatin, which simultaneously resulted in reduced hormone-dependent transcriptional responses (Galliher-Beckley et al, 2011). Interestingly, p38 MAPK has been shown to be active in alveolar macrophages of asthmatic patients who exhibited poor response to glucocorticoids when compared to patients with a normal response (Bhavsar et al, 2008). In contrast, p38 MAPK has also been shown to phosphorylate Ser211 in human leukemic cells, leading to increased dexamethasone-driven apoptosis (Khan et al, 2017). This suggests that p38 MAPK kinase phosphorylation of GR impacts ligand-independent GR signaling in a cell-specific manner. In breast cancer models, p38 MAPK signaling is emerging as an important mediator of stem cell biology (Grun et al, 2019; Lu et al, 2018; Xu et al, 2018) and other non-proliferative states that are relevant to cancer biology (discussed below).

STUDIES of CANCER CELL BIOLOGY:

PR regulation of breast cancer cell proliferation vs. stem cell biology.

Most cancer therapies were historically designed to target rapidly dividing tumor cells. In the context of ER-positive breast cancer, tumor cells are dependent on ER transcriptional activity to promote proliferation. Thus, endocrine therapies that target ER function (i.e. selective ER modulators [SERMs], selective ER degraders [SERDs], and aromatase inhibitors [AIs]) inhibit proliferation and are very effective treatments for ER-positive breast cancer. Yet, the benefits of endocrine therapy are not sustained long-term in 10% to 41% of patients who suffer from late recurrence (Pan et al, 2017). It is hypothesized that non-proliferative cell states, such as quiescence/tumor cell dormancy, cell survival, plasticity, and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) as well as cancer stem cells (CSCs) are not well-targeted by standard cancer therapies. Indeed, a growing body of literature suggests that breast CSCs are resistant to current therapeutic approaches (Easwaran et al, 2014; Piva et al, 2014). In fact, these non-proliferative cell states are induced or maintained in response to cellular stress signaling and the selective pressure created by radiation, chemo- and endocrine therapy that is largely cytostatic rather than cytotoxic, ultimately contributing to therapy resistant cancer recurrence and metastasis. For example, chemotherapy has been shown to increase CD44+/CD24- CSC populations and tumorsphere formation in breast cancer patients (Li et al, 2008). In particular, CSCs tend to be non-proliferative, allowing them to readily evade standard therapies and expand over time (Fillmore & Kuperwasser, 2008). Recent studies utilizing mouse models of prolactin-induced ER+ breast cancer showed that treatment with antiestrogens such as fulvestrant or tamoxifen reproducibly stimulated breast CSC self-renewal (Shea et al, 2018). These studies suggest that antiestrogen therapies may initially slow tumor growth, but also concurrently promote unwanted side effects by evoking plasticity and regenerative CSC activity in largely non-proliferative cancer cell compartments.

The proliferative effects of progestins in normal breast development are well-established. Progestins are proliferative in the breast (McGowan et al, 2007) and PR-B is the predominant isoform involved in normal mammary gland tissue expansion during breast development after puberty (Mulac-Jericevic et al, 2003). Mouse models lacking PR-B, but not PR-A, exhibited defects in mammary gland branching and alveologenesis (Mulac-Jericevic et al, 2003). Conversely, using knockout mouse models, PR-A has been shown to be required for normal uterine development and fertility (Conneely et al, 2001). More recently, PRs have been found to promote non-proliferative phenotypes that include cell survival and regulation of cancer stem/stem-like cell self-renewal. For example, progestin stimulation of PR+ mammary epithelial cells induced transcription and secretion of mitogenic factors such as Wnts, Areg, HB-EGF, and RANKL leading to proliferation of neighboring PR- cells (Fata et al, 2001; Tanos et al, 2013). Separate studies implicated these same PR signaling outputs (i.e. RANKL and Wnt4) in the maintenance and expansion of the normal mammary gland stem compartment (Asselin-Labat et al, 2010; Joshi et al, 2010). These studies have been extended to show that PR regulates the breast CSC compartment (Axlund et al, 2013; Cittelly et al, 2013; Finlay-Schultz & Sartorius, 2015; Goodman et al, 2016; Hilton et al, 2014), and recent work has further shown that PR isoforms have divergent roles in supporting breast CSC properties using ER+ breast cancer cell line models that either lack both PRs or express only PR-A, only PR-B, or both isoforms (Truong et al, 2019). Measurement of breast CSC markers in these models indicated that although PR-A+ breast cancer cells were only weakly proliferative in soft-agar, they formed abundant tumorspheres that were enriched for both ALDH+ and CD44+/CD24- cell populations relative to PR-B+ cells (which formed fewer but larger spheres), suggesting a reversible phenotypic flip from pro-proliferative (PR-B-driven) to non-proliferative CSC (PR-A-driven) programs. Accordingly, S294A PR-A mutant models were impaired with regard to ALDH+ tumorsphere formation, yet exhibited increased proliferation in soft agar (Truong et al, 2019). These studies suggest tight linkage between highly plastic (i.e. proliferative versus CSC) regulated cell fates, and implicates PR isoform-specific modulation.

Divergent roles of PR isoforms may be explained by isoform-specific transcriptional control of overlapping but distinct gene programs which, in part, is directed by PTMs. Notably, phospho-Ser294 species are required for both PR-A- and PR-B-induced tumorsphere formation (Knutson et al, 2017; Truong et al, 2019). However, phospho-PR-A is preferentially recruited to promoters of CSC-associated genes (e.g. Wnt4, KLF4, NOTCH2) relative to phospho-PR-B; PR isoform recruitment was significantly reduced in phospho-mutant models (i.e. S294A). Of note, the effect of PR isoforms on CSC markers and tumorsphere formation was independent of exogenously added progestin (i.e. ligand-independent in defined media), and the addition of progestin did not have a significant effect on tumorsphere number or size. In the context of endocrine therapy resistance, SRs may promote tumor progression via ligand-independent mechanisms, resulting from the upregulation of growth factor and/or stress signaling pathways that occurs following hormone withdrawal (Need et al, 2015; Nicholson et al, 2004). Relevant to this concept, EGF induces MAPK-dependent and ligand-independent PR Ser294 phosphorylation, which greatly enhanced PR-A and PR-B driven secondary tumorsphere formation, an in vitro readout of CSC self-renewal (Truong et al, 2019); mutation of PR Ser294 to Ala blocked these effects. These findings indicate that PR Ser294 phosphorylation is a crucial event that defines both PR-A and PR-B actions in the regulation of CSC populations; the increased potency of PR-A over PR-B as a driver of breast cancer stemness may be explained by its greater stability (Faivre et al, 2008) and resistance to deSUMOylation relative to PR-B (Daniel et al, 2007). Understanding how SRs contribute to cancer cell fate transitions plasticity, heterogeneity, and other non-proliferative cancer cell biologies is important for preventing and targeting therapy resistance.

PR signaling impacts the cell cycle

One functional characteristic of CSCs is the ability to maintain a cellular quiescence, reversibly existing in the G0 phase of the cell cycle (Bighetti-Trevisan et al, 2019). This quiescent state allows for long-term survival in response to cellular or microenvironmental stress (i.e. chemotherapy, hypoxia, etc.). Signaling molecules that regulate quiescence include cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (i.e. p21, p27, and p57), as well as the members of the FOXO family of transcription factors. Our prior work showed that PRs regulate the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p21 and FOXO1 to promote cellular senescence, the irreversible exit from the cell cycle (i.e. permanent accumulation in G0), in ovarian cancer models (Diep et al, 2013; Diep et al, 2016). Senescence, FOXO1 and p21 gene expression, and PR Ser294 phosphorylation were induced by progestin (ligand-dependent). Chemical inhibition of FOXO1 inhibited PR Ser294 phosphorylation and the PR-dependent senescence phenotype. In these studies, PR-B was the dominant isoform required for induction of both FOXO1 and p21 expression as well as progestin-induced cellular senescence, while PR-A repressed these genes and failed to induce a senescent state upon treatment of ovarian cancer cells with progestins.

Many of the same signaling molecules and transcription factors regulate both senescence and quiescence. While a direct link between PR and CSC quiescence has not yet been established in ER+/PR+ breast cancer models, it is possible that context dependent signals, such as breast versus ovarian cells of origin, cancer type-specific or MAPK/CDK signaling pathway activation, and/or ligand-independent PR phosphorylation, will promote a PR-dependent cellular quiescence that contributes to CSC survival. In support of this, FOXO1 expression increased PR Ser294 phosphorylation and promoted ALDH+ tumorsphere formation in both PR-A and PR-B expressing breast cancer models (Truong et al, 2019). Accordingly, inhibition of PR and FOXO1 with onapristone and AS1842856, respectively, had a synergistic inhibitory effect on CSC self-renewal in multiple breast cancer models. Future studies will examine the cooperative effect of PR isoforms, FOXO1, and p21 on CSC quiescence/tumor cell dormancy in ER+ breast cancer models.

GR promotes triple negative breast cancer cell survival, migration, and invasion

As with PR isoforms, the effects of GR on breast cancer biology are also highly context dependent and most relevant to non-proliferative cancer cell fates. Like PR expression, GR expression in ER+ luminal breast cancer is associated with a better prognosis. In sharp contrast however, high GR expression is associated with more aggressive triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) biology and poor prognosis when compared to patients with low GR expression (Pan et al, 2011). In TNBC models, expression of GR and/or GR-associated target genes (i.e. Brk/PTK6) have been associated with pro-survival signaling, EMT and cellular migration/invasion in vitro as well as metastasis in vivo (Lofgren et al, 2011; Regan Anderson et al, 2018; Regan Anderson et al, 2016; Regan Anderson et al, 2013). Recently, activation of GR with glucocorticoids was shown to drive breast cancer metastasis in vivo (Obradovic et al, 2019).

Cancer cell survival or resisting cell death is an original hallmark of cancer (Hanahan & Weinberg, 2000). Cellular mechanisms associated with cell survival include the regulation of pro- and anti-apoptotic BH3 family proteins, the extrinsic death receptor signaling molecules, and the intrinsic caspase and apoptosome proteins that ultimately lead to cell death. Intrinsic activation of cell death pathways is often initiated by cell stress caused by DNA damage, ROS production, or metabolic/nutrient stress. GR is a long-established sensor of physiologic (i.e. hormonal) stress, and more recent data indicates that GR is also an exquisite sensor of cellular stress and stress signaling within the TME. In response to systemic glucocorticoid exposure, GR is known to promote cell death in lymphocytes and monocytes in order to reduce inflammation (Strehl et al, 2019). However, activation of GR also promotes cell survival in a variety of epithelial cell types, including in breast cancer models. In studies of TNBC, ligand-dependent and ligand-independent GR activation have been shown to promote expression of pro-survival proteins (Regan Anderson et al, 2018; Wu et al, 2004). For example, GR promotes breast tumor kinase (Brk/PTK6) expression in response to dexamethasone (ligand-dependent), and also in response to hypoxia, cell stress induced by chemotherapy, and anoikis (ligand-independent). In TNBC models, hypoxia, paclitaxel, 5-FU, and non-adherent culture all led to p38-MAPK-dependent GR Ser134 phosphorylation and ligand-independent activation of gene programs implicated in cellular stress-response (Regan Anderson et al, 2018; Regan Anderson et al, 2016). GR-dependent Brk/PTK6 induction protected cells from chemotherapy-induced cell death and promoted cell migration (Regan Anderson et al, 2018). These studies further our mechanistic understanding of how GR and glucocorticoids promote plasticity in order to protect TNBC cells from cell stress and chemotherapy-induced cell death and may have clinical implications for the routine use of high-dose steroids prior to chemotherapy.

Cells sense both local external (TME) and internal stress (hypoxia) via activation of JNKs and p38 MAPKs, also historically known as stress-activated protein kinases or SAPKs (Laderoute et al, 1999; Sumbayev & Yasinska, 2005). Notably, upregulation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway has emerged as a mechanism by which tumor cells increase their metastatic capacity. Mechanistic studies have shown that p38 MAPK signaling promotes the invasive and metastatic capacities of breast tumor cells (Limoge et al, 2017). As discussed above, phosphorylation of Ser134 GR is p38 MAPK-dependent in osteosarcoma (Galliher-Beckley et al, 2011) and breast cancer models (Regan Anderson et al, 2016). The role of hypoxia/HIFs in promoting EMT and increased migration of TNBC cell models is well-established (Brooks et al, 2016; Tirpe et al, 2019); our most recent studies indicate that GR is a principle driver of TME- (i.e. cytokine) and stress-induced TNBC migration, specifically via p38 MAPK-dependent GR Ser134 phosphorylation (C Perez Kerkvliet and CA Lange, unpublished results). While these effects in TNBC cell models were ligand-independent, others have reported that glucocorticoid treatment promoted metastasis in vivo using patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models (Obradovic et al, 2019). It is important to note that GR activation by glucocorticoids has been shown to suppress the migration of immune cells, highlighting the tissue and cell-specific roles of GR/phospho-GR (Stahn & Buttgereit, 2008), and underscoring the need to select patients using appropriate biomarkers of phospho-GR signaling in GR+ TNBC patients.

Ligand-independent SRs are important therapeutic targets

Phospho-SR species are predicted to be valuable biomarkers of aggressive breast cancer behavior. Detection of phosphorylated receptors or their respective target gene signatures may provide a useful means by which to further classify more aggressive breast tumors and thus estimate risk of therapy-resistant recurrence. An important caveat to targeting phospho-SR species is that these species may be insensitive to existing receptor antagonists; phosphorylation events confer partial agonist activity to SR antagonists (Wardell et al, 2010) and phospho-ER species are strongly implicated in the development of tamoxifen resistance (Kastrati et al, 2019; Likhite et al, 2006). Notably, RU486 (an antagonist for both PR and GR) does not significantly reduce ligand-independent phosphorylation of PR or GR. However, at least in vitro, ligand-independent actions of phospho-SRs that are not further stimulated by agonists are often sensitive to selected antagonists. For example, ER-scaffolding actions of PR-B appear to be insensitive to type I antagonists (i.e. RU486) that induce PR Ser294 phosphorylation levels similar to that of PR agonists (Daniel et al, 2015), but are blocked by type II antagonists (i.e. onapristone) that also block ligand-induced PR Ser294 phosphorylation (Beck et al, 1996). Similarly, high basal TNBC cell migration is only weakly stimulated by the GR agonist dexamethasone, but completely blocked by the GR antagonist, RU486 (Perez Kerkvliet et al, in press). Thus, targeting phospho-SR species may be possible using existing agents or newer more selective SR antagonists paired with the appropriate MEK/MAPK or CDK signaling pathway inhibitors (Table I). Progestins (megestrol acetate or Megase) as well as antiprogestins (RU486, onapristone) were effective in early clinical trials, particularly when paired with Tam or ICI 162384 (Klijn et al, 2000; Nishino et al, 1994; Robertson et al, 1989; Robertson et al, 1999), but had significant liver toxicity, likely due, in part, to cross-reactivity with ubiquitously expressed GRs. This problem may be overcome by use of lower dose or timed-release antiprogestin preparations, as in the case of Apristor (Context Therapeutics, Inc), a clinical formulation of onapristone. Historical clinical studies that clearly implicated progestins (namely MPA, a PR agonist) in elevated breast cancer risk (MWS, 2003; Rossouw et al, 2002; Soini et al, 2016) have renewed interest in targeting PRs as part of combination endocrine therapies. As a result, selective antiprogestins (onapristone, telapristone acetate) have re-entered Phase I-II trials with encouraging results (Cottu et al, 2018; Lee et al, 2020). Similarly, GR antagonists (i.e. RU486) are being tested in TNBC clinical trials (Nanda et al, 2016). Of concern is that the science of PR and GR (i.e. in breast cancer models), while growing, lags far behind that of ER or even AR and fewer ligands are available for pre-clinical modeling of PR or GR-driven actions relative to a wealth of selective receptor modulators for ER or AR. Before selective SR modulators can be successfully combined with existing therapies, the knowledge gap of the roles that PR/GR play as modulators of other SR (i.e. ER or AR) actions and the impact of phosphorylation events to SRs on hormone responsiveness and aggressive breast cancer biology must be elucidated.

Table 1.

PR and GR post-translational modifications and associated ligand-dependent (LD) and ligand-independent (LI) biological outcomes.

| Steroid Receptor | PTM | Kinase Pathway | Biological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PR | S81 | CK2 | Proliferation, survival, migration, transcriptional regulation (Hagan 2011) |

| PR | S294 (Phosphorylation) | MAPK, CDK | Nuclear localization (LI; Qui & Lange, 2003), turnover, transcriptional regulation (LD; Daniel 2009, Shen 2001), proliferation (Daniel 2007), stemness (Truong 2019), senescence (Diep 2013), cell cycle progression (Moore 2000) |

| PR | S345 (Phosphorylation) | MAPK, CDK2 | Proliferation, migration (Faivre 2008, Dressing 2013) |

| PR | K388 (SUMOylation) | --- | Transcriptional regulation, slows PR turnover (Abdel-Hafiz 2002, Daniel 2007) |

| PR | S400 (Phosphorylation) | CDK2 | Cell cycle progression, LI transcription, (Zhang 1997, Pierson-Mullany 2004, Wardell 2010) |

| PR | S676 (Phosphorylation) | CDK2 | Transcriptional activity (Knotts 2001) |

| PR | K638-K641 (KxKK, Acetylation consensus sequence) | --- | Disrupts nuclear translocation and delays MAPK-induced Ser345 and Ser294 phosphorylation (Daniel 2010) |

| GR | S134 (Phosphorylation) | p38 | Response to stress-activating stimuli/p38 MAPK, hypoxia (Regan Anderson 2016), stress-induced survival, migration, and stemness (Perez Kerkvliet 2020) |

| GR | S211 (Phosphorylation) | p38 | Apoptosis (LD; Khan 2017) |

| GR | S404 (Phosphorylation) | GSK-3 | Turnover, resistance to LD apoptosis (Galliher-Beckley 2008) |

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, SRs act as highly context dependent sensors of the cellular signaling environment underpinned by PTMs that are intricately controlled by growth factors and cytokines within the tumor microenvironment and their intracellular MAPK effectors. Phospho-PR and -GR exhibit extensive functional redundancy with regard to shared ligands and binding sites in chromatin/target gene overlap. Both SRs are also capable of initiating feed-forward signaling loops, a paradigm in which their target gene products further phosphorylate the initiating SR, leading to a sustained signal that can be maintained indefinitely in the absence of steroid ligands. Understanding this mechanism is critical for the treatment of both luminal ER+ and triple negative breast cancers; sustained phospho-SR signaling may contribute to the emergence of therapy-resistant biologies in a minority population of cancer cells, including non-proliferative stem or dormant cell states, and cell fates associated with EMT, migration, survival, and therapy resistance. Therapeutically, targeting this paradigm will likely involve expanding hormonal modulation/kinase inhibitor repertoires to include agents specifically targeting phospho-SRs and their target genes.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants R01CA236948 (CAL and JHO), R01 CA159712 (CAL), F32 CA210340 (THT), T32 HL007741 (THT), and NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR002494 (ARD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The Tickle Family Land Grant Endowed Chair in Breast Cancer Research (CAL) also supported this work.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST

Carol A. Lange serves on the Board of Scientific Advisors for Context Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Hafiz H, Takimoto GS, Tung L & Horwitz KB (2002) The inhibitory function in human progesterone receptor N termini binds SUMO-1 protein to regulate autoinhibition and transrepression. J Biol Chem, 277(37), 33950–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ao Z, Shah SH, Machlin LM, Parajuli R, Miller PC, Rawal S, Williams AJ, Cote RJ, Lippman ME, Datar RH, et al. (2015) Identification of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts in Circulating Blood from Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancer Res, 75(22), 4681–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino G, Wiechmann L, Osborne CK & Schiff R (2008) Crosstalk between the estrogen receptor and the HER tyrosine kinase receptor family: molecular mechanism and clinical implications for endocrine therapy resistance. Endocr Rev, 29(2), 217–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asselin-Labat ML, Vaillant F, Sheridan JM, Pal B, Wu D, Simpson ER, Yasuda H, Smyth GK, Martin TJ, Lindeman GJ, et al. (2010) Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature, 465(7299), 798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aupperlee MD, Smith KT, Kariagina A & Haslam SZ (2005) Progesterone receptor isoforms A and B: temporal and spatial differences in expression during murine mammary gland development. Endocrinology, 146(8), 3577–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axlund SD, Yoo BH, Rosen RB, Schaack J, Kabos P, Labarbera DV & Sartorius CA (2013) Progesterone-inducible cytokeratin 5-positive cells in luminal breast cancer exhibit progenitor properties. Horm Cancer, 4(1), 36–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballare C, Uhrig M, Bechtold T, Sancho E, Di Domenico M, Migliaccio A, Auricchio F & Beato M (2003) Two domains of the progesterone receptor interact with the estrogen receptor and are required for progesterone activation of the c-Src/Erk pathway in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol, 23(6), 1994–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CA, Zhang Y, Weigel NL & Edwards DP (1996) Two types of anti-progestins have distinct effects on site-specific phosphorylation of human progesterone receptor. J Biol Chem, 271(2), 1209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar P, Hew M, Khorasani N, Torrego A, Barnes PJ, Adcock I & Chung KF (2008) Relative corticosteroid insensitivity of alveolar macrophages in severe asthma compared with non-severe asthma. Thorax, 63(9), 784–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bighetti-Trevisan RL, Sousa LO, Castilho RM & Almeida LO (2019) Cancer Stem Cells: Powerful Targets to Improve Current Anticancer Therapeutics. Stem cells international, 2019, 9618065–9618065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom JW (2004) Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways: therapeutic targets in steroid resistance? J Allergy Clin Immunol, 114(5), 1055–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boonyaratanakornkit V, Scott MP, Ribon V, Sherman L, Anderson SM, Maller JL, Miller WT & Edwards DP (2001) Progesterone receptor contains a proline-rich motif that directly interacts with SH3 domains and activates c-Src family tyrosine kinases. Mol Cell, 8(2), 269–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DL, Schwab LP, Krutilina R, Parke DN, Sethuraman A, Hoogewijs D, Schorg A, Gotwald L, Fan M, Wenger RH, et al. (2016) ITGA6 is directly regulated by hypoxia-inducible factors and enriches for cancer stem cell activity and invasion in metastatic breast cancer models. Mol Cancer, 15, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro NE & Lange CA (2010) Breast tumor kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 mediate Met receptor signaling to cell migration in breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res, 12(4), R60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cittelly DM, Finlay-Schultz J, Howe EN, Spoelstra NS, Axlund SD, Hendricks P, Jacobsen BM, Sartorius CA & Richer JK (2013) Progestin suppression of miR-29 potentiates dedifferentiation of breast cancer cells via KLF4. Oncogene, 32(20), 2555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condon JC, Hardy DB, Kovaric K & Mendelson CR (2006) Up-regulation of the progesterone receptor (PR)-C isoform in laboring myometrium by activation of nuclear factor-kappaB may contribute to the onset of labor through inhibition of PR function. Mol Endocrinol, 20(4), 764–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conneely OM, Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP & De Mayo FJ (2001) Reproductive functions of the progesterone receptor isoforms: lessons from knock-out mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 179(1–2), 97–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottu PH, Bonneterre J, Varga A, Campone M, Leary A, Floquet A, Berton-Rigaud D, Sablin MP, Lesoin A, Rezai K, et al. (2018) Phase I study of onapristone, a type I antiprogestin, in female patients with previously treated recurrent or metastatic progesterone receptor-expressing cancers. PLoS One, 13(10), e0204973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AR, Faivre EJ & Lange CA (2007) Phosphorylation-dependent antagonism of sumoylation derepresses progesterone receptor action in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol, 21(12), 2890–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AR, Gaviglio AL, Czaplicki LM, Hillard CJ, Housa D & Lange CA (2010) The progesterone receptor hinge region regulates the kinetics of transcriptional responses through acetylation, phosphorylation, and nuclear retention. Mol Endocrinol, 24(11), 2126–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AR, Gaviglio AL, Knutson TP, Ostrander JH, D’Assoro AB, Ravindranathan P, Peng Y, Raj GV, Yee D & Lange CA (2015) Progesterone receptor-B enhances estrogen responsiveness of breast cancer cells via scaffolding PELP1- and estrogen receptor-containing transcription complexes. Oncogene, 34(4), 506–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel AR & Lange CA (2009) Protein kinases mediate ligand-independent derepression of sumoylated progesterone receptors in breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 106(34), 14287–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL & Tindall DJ (2008) Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res, 68(13), 5469–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep CH, Charles NJ, Gilks CB, Kalloger SE, Argenta PA & Lange CA (2013) Progesterone receptors induce FOXO1-dependent senescence in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Cycle, 12(9), 1433–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep CH, Daniel AR, Mauro LJ, Knutson TP & Lange CA (2015) Progesterone action in breast, uterine, and ovarian cancers. J Mol Endocrinol, 54(2), R31–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep CH, Knutson TP & Lange CA (2016) Active FOXO1 Is a Key Determinant of Isoform-Specific Progesterone Receptor Transactivation and Senescence Programming. Mol Cancer Res, 14(2), 141–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressing GE, Knutson TP, Schiewer MJ, Daniel AR, Hagan CR, Diep CH, Knudsen KE & Lange CA (2014) Progesterone receptor-cyclin D1 complexes induce cell cycle-dependent transcriptional programs in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol, 28(4), 442–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duma D, Jewell CM & Cidlowski JA (2006) Multiple glucocorticoid receptor isoforms and mechanisms of post-translational modification. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 102(1–5), 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easwaran H, Tsai HC & Baylin SB (2014) Cancer epigenetics: tumor heterogeneity, plasticity of stem-like states, and drug resistance. Mol Cell, 54(5), 716–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faivre EJ, Daniel AR, Hillard CJ & Lange CA (2008) Progesterone receptor rapid signaling mediates serine 345 phosphorylation and tethering to specificity protein 1 transcription factors. Mol Endocrinol, 22(4), 823–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fata JE, Chaudhary V & Khokha R (2001) Cellular turnover in the mammary gland is correlated with systemic levels of progesterone and not 17beta-estradiol during the estrous cycle. Biol Reprod, 65(3), 680–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore CM & Kuperwasser C (2008) Human breast cancer cell lines contain stem-like cells that self-renew, give rise to phenotypically diverse progeny and survive chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res, 10(2), R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay-Schultz J & Sartorius CA (2015) Steroid hormones, steroid receptors, and breast cancer stem cells. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia, 20(1–2), 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher-Beckley AJ, Williams JG & Cidlowski JA (2011) Ligand-independent phosphorylation of the glucocorticoid receptor integrates cellular stress pathways with nuclear receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol, 31(23), 4663–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulianelli S, Cerliani JP, Lamb CA, Fabris VT, Bottino MC, Gorostiaga MA, Novaro V, Gongora A, Baldi A, Molinolo A, et al. (2008) Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts activate progesterone receptors and induce hormone independent mammary tumor growth: A role for the FGF-2/FGFR-2 axis. Int J Cancer, 123(11), 2518–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulianelli S, Riggio M, Guillardoy T, Perez Pinero C, Gorostiaga MA, Sequeira G, Pataccini G, Abascal MF, Toledo MF, Jacobsen BM, et al. (2019) FGF2 induces breast cancer growth through ligand-independent activation and recruitment of ERalpha and PRBDelta4 isoform to MYC regulatory sequences. Int J Cancer, 145(7), 1874–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CR, Sato T, Peck AR, Girondo MA, Yang N, Liu C, Yanac AF, Kovatich AJ, Hooke JA, Shriver CD, et al. (2016) Steroid induction of therapy-resistant cytokeratin-5-positive cells in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer through a BCL6-dependent mechanism. Oncogene, 35(11), 1373–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D, Callaway C, Pascal BD, Kumar R, Edwards DP & Griffin PR (2014) Influence of domain interactions on conformational mobility of the progesterone receptor detected by hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry. Structure, 22(7), 961–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grun D, Adhikary G & Eckert RL (2019) NRP-1 interacts with GIPC1 and SYX to activate p38 MAPK signaling and cancer stem cell survival. Mol Carcinog, 58(4), 488–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan CR, Regan TM, Dressing GE & Lange CA (2011) ck2-dependent phosphorylation of progesterone receptors (PR) on Ser81 regulates PR-B isoform-specific target gene expression in breast cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol, 31(12), 2439–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D & Weinberg RA (2000) The Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell, 100(1), 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton HN, Santucci N, Silvestri A, Kantimm S, Huschtscha LI, Graham JD & Clarke CL (2014) Progesterone stimulates progenitor cells in normal human breast and breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 143(3), 423–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini H, Obradovic MMS, Hoffmann M, Harper KL, Sosa MS, Werner-Klein M, Nanduri LK, Werno C, Ehrl C, Maneck M, et al. (2016) Early dissemination seeds metastasis in breast cancer. Nature, 540(7634), 552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irusen E, Matthews JG, Takahashi A, Barnes PJ, Chung KF & Adcock IM (2002) p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase-induced glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation reduces its activity: role in steroid-insensitive asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 109(4), 649–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismaili N & Garabedian MJ (2004) Modulation of glucocorticoid receptor function via phosphorylation. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1024, 86–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi PA, Jackson HW, Beristain AG, Di Grappa MA, Mote PA, Clarke CL, Stingl J, Waterhouse PD & Khokha R (2010) Progesterone induces adult mammary stem cell expansion. Nature, 465(7299), 803–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastrati I, Semina S, Gordon B & Smart E (2019) Insights into how phosphorylation of estrogen receptor at serine 305 modulates tamoxifen activity in breast cancer. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology, 483, 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayahara M, Ohanian J, Ohanian V, Berry A, Vadlamudi R & Ray DW (2008) MNAR functionally interacts with both NH2- and COOH-terminal GR domains to modulate transactivation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 295(5), E1047–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SH, McLaughlin WA & Kumar R (2017) Site-specific phosphorylation regulates the structure and function of an intrinsically disordered domain of the glucocorticoid receptor. Sci Rep, 7(1), 15440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klijn JGM, Beex LVAM, Mauriac L, van Zijl JA, Veyret C, Wildiers J, Jassem J, Piccart M, Burghouts J, Becquart D, et al. (2000) Combined Treatment With Buserelin and Tamoxifen in Premenopausal Metastatic Breast Cancer: a Randomized Study. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 92(11), 903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knotts TA, Orkiszewski RS, Cook RG, Edwards DP & Weigel NL (2001) Identification of a phosphorylation site in the hinge region of the human progesterone receptor and additional amino-terminal phosphorylation sites. J Biol Chem, 276(11), 8475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson TP, Daniel AR, Fan D, Silverstein KA, Covington KR, Fuqua SA & Lange CA (2012) Phosphorylated and sumoylation-deficient progesterone receptors drive proliferative gene signatures during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res, 14(3), R95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson TP, Truong TH, Ma S, Brady NJ, Sullivan ME, Raj G, Schwertfeger KL & Lange CA (2017) Posttranslationally modified progesterone receptors direct ligand-specific expression of breast cancer stem cell-associated gene programs. J Hematol Oncol, 10(1), 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstic MD, Rogatsky I, Yamamoto KR & Garabedian MJ (1997) Mitogen-activated and cyclin-dependent protein kinases selectively and differentially modulate transcriptional enhancement by the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Cell Biol, 17(7), 3947–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R & Thompson EB (2005) Gene regulation by the glucocorticoid receptor: structure:function relationship. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol, 94(5), 383–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R & Thompson EB (2019) Role of Phosphorylation in the Modulation of the Glucocorticoid Receptor’s Intrinsically Disordered Domain. Biomolecules, 9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laderoute KR, Mendonca HL, Calaoagan JM, Knapp AM, Giaccia AJ & Stork PJ (1999) Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) expression is induced by low oxygen conditions found in solid tumor microenvironments. A candidate MKP for the inactivation of hypoxia-inducible stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase activity. J Biol Chem, 274(18), 12890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb CA, Fabris VT, Jacobsen B, Molinolo AA & Lanari C (2018) Biological and clinical impact of imbalanced progesterone receptor isoform ratios in breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee O, Sullivan ME, Xu Y, Rogers C, Muzzio M, Helenowski I, Shidfar A, Zeng Z, Singhal H, Jovanovic B, et al. (2020) Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulators in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase II Window-of-Opportunity Trial Using Telapristone Acetate. Clin Cancer Res, 26(1), 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C, Osborne CK, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Pavlick A, Zhang X, Chamness GC, et al. (2008) Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst, 100(9), 672–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likhite VS, Stossi F, Kim K, Katzenellenbogen BS & Katzenellenbogen JA (2006) Kinase-Specific Phosphorylation of the Estrogen Receptor Changes Receptor Interactions with Ligand, Deoxyribonucleic Acid, and Coregulators Associated with Alterations in Estrogen and Tamoxifen Activity. Molecular Endocrinology, 20(12), 3120–3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limoge M, Safina A, Truskinovsky AM, Aljahdali I, Zonneville J, Gruevski A, Arteaga CL & Bakin AV (2017) Tumor p38MAPK signaling enhances breast carcinoma vascularization and growth by promoting expression and deposition of pro-tumorigenic factors. Oncotarget, 8(37), 61969–61981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren KA, Ostrander JH, Housa D, Hubbard GK, Locatelli A, Bliss RL, Schwertfeger KL & Lange CA (2011) Mammary gland specific expression of Brk/PTK6 promotes delayed involution and tumor formation associated with activation of p38 MAPK. Breast Cancer Res, 13(5), R89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Tran L, Park Y, Chen I, Lan J, Xie Y & Semenza GL (2018) Reciprocal Regulation of DUSP9 and DUSP16 Expression by HIF1 Controls ERK and p38 MAP Kinase Activity and Mediates Chemotherapy-Induced Breast Cancer Stem Cell Enrichment. Cancer Res, 78(15), 4191–4202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu NZ & Cidlowski JA (2005) Translational regulatory mechanisms generate N-terminal glucocorticoid receptor isoforms with unique transcriptional target genes. Mol Cell, 18(3), 331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason SA & Housley PR (1993) Site-directed mutagenesis of the phosphorylation sites in the mouse glucocorticoid receptor. J Biol Chem, 268(29), 21501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JG, Ito K, Barnes PJ & Adcock IM (2004) Defective glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation and altered histone acetylation patterns in glucocorticoid-resistant patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 113(6), 1100–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan EM, Russell AJ, Boonyaratanakornkit V, Saunders DN, Lehrbach GM, Sergio CM, Musgrove EA, Edwards DP & Sutherland RL (2007) Progestins reinitiate cell cycle progression in antiestrogen-arrested breast cancer cells through the B-isoform of progesterone receptor. Cancer Res, 67(18), 8942–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio A, Piccolo D, Castoria G, Di Domenico M, Bilancio A, Lombardi M, Gong W, Beato M & Auricchio F (1998) Activation of the Src/p21ras/Erk pathway by progesterone receptor via cross-talk with estrogen receptor. Embo j, 17(7), 2008–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda TB, Voss TC & Hager GL (2013) High-throughput fluorescence-based screen to identify factors involved in nuclear receptor recruitment to response elements. Methods Mol Biol, 1042, 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed H, Russell IA, Stark R, Rueda OM, Hickey TE, Tarulli GA, Serandour AA, Birrell SN, Bruna A, Saadi A, et al. (2015) Progesterone receptor modulates ERalpha action in breast cancer. Nature, 523(7560), 313–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mote PA, Bartow S, Tran N & Clarke CL (2002) Loss of co-ordinate expression of progesterone receptors A and B is an early event in breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 72(2), 163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mote PA, Gompel A, Howe C, Hilton HN, Sestak I, Cuzick J, Dowsett M, Hugol D, Forgez P, Byth K, et al. (2015) Progesterone receptor A predominance is a discriminator of benefit from endocrine therapy in the ATAC trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 151(2), 309–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulac-Jericevic B, Lydon JP, DeMayo FJ & Conneely OM (2003) Defective mammary gland morphogenesis in mice lacking the progesterone receptor B isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 100(17), 9744–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MWS (2003) Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. The Lancet, 362(9382), 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda R, Stringer-Reasor EM, Saha P, Kocherginsky M, Gibson J, Libao B, Hoffman PC, Obeid E, Merkel DE, Khramtsova G, et al. (2016) A randomized phase I trial of nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel with or without mifepristone for advanced breast cancer. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Need EF, Selth LA, Trotta AP, Leach DA, Giorgio L, O’Loughlin MA, Smith E, Gill PG, Ingman WV, Graham JD, et al. (2015) The unique transcriptional response produced by concurrent estrogen and progesterone treatment in breast cancer cells results in upregulation of growth factor pathways and switching from a Luminal A to a Basal-like subtype. BMC cancer, 15, 791–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson RI, Staka C, Boyns F, Hutcheson IR & Gee JM (2004) Growth factor-driven mechanisms associated with resistance to estrogen deprivation in breast cancer: new opportunities for therapy. Endocr Relat Cancer, 11(4), 623–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino Y, Schneider MR & Michna H (1994) Enhancement of the antitumor efficacy of the antiprogestin, onapristone, by combination with the antiestrogen, ICI 164384. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 120(5), 298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley RH & Cidlowski JA (2013) The biology of the glucocorticoid receptor: new signaling mechanisms in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 132(5), 1033–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obradovic MMS, Hamelin B, Manevski N, Couto JP, Sethi A, Coissieux MM, Munst S, Okamoto R, Kohler H, Schmidt A, et al. (2019) Glucocorticoids promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature, 567(7749), 540–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan D, Kocherginsky M & Conzen SD (2011) Activation of the glucocorticoid receptor is associated with poor prognosis in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res, 71(20), 6360–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan H, Gray R, Braybrooke J, Davies C, Taylor C, McGale P, Peto R, Pritchard KI, Bergh J, Dowsett M, et al. (2017) 20-Year Risks of Breast-Cancer Recurrence after Stopping Endocrine Therapy at 5 Years. N Engl J Med, 377(19), 1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierson-Mullany LK & Lange CA (2004) Phosphorylation of progesterone receptor serine 400 mediates ligand-independent transcriptional activity in response to activation of cyclin-dependent protein kinase 2. Mol Cell Biol, 24(24), 10542–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piva M, Domenici G, Iriondo O, Rabano M, Simoes BM, Comaills V, Barredo I, Lopez-Ruiz JA, Zabalza I, Kypta R, et al. (2014) Sox2 promotes tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer cells. EMBO Mol Med, 6(1), 66–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presul E, Schmidt S, Kofler R & Helmberg A (2007) Identification, tissue expression, and glucocorticoid responsiveness of alternative first exons of the human glucocorticoid receptor. J Mol Endocrinol, 38(1–2), 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan Anderson TM, Ma S, Perez Kerkvliet C, Peng Y, Helle TM, Krutilina RI, Raj GV, Cidlowski JA, Ostrander JH, Schwertfeger KL, et al. (2018) Taxol Induces Brk-dependent Prosurvival Phenotypes in TNBC Cells through an AhR/GR/HIF-driven Signaling Axis. Mol Cancer Res, 16(11), 1761–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan Anderson TM, Ma SH, Raj GV, Cidlowski JA, Helle TM, Knutson TP, Krutilina RI, Seagroves TN & Lange CA (2016) Breast Tumor Kinase (Brk/PTK6) Is Induced by HIF, Glucocorticoid Receptor, and PELP1-Mediated Stress Signaling in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res, 76(6), 1653–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regan Anderson TM, Peacock DL, Daniel AR, Hubbard GK, Lofgren KA, Girard BJ, Schorg A, Hoogewijs D, Wenger RH, Seagroves TN, et al. (2013) Breast tumor kinase (Brk/PTK6) is a mediator of hypoxia-associated breast cancer progression. Cancer Res, 73(18), 5810–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JFR, Williams MR, Todd J, Nicholson RI, Morgan DAL & Blamey RW (1989) Factors predicting the response of patients with advanced breast cancer to endocrine (Megace) therapy. European Journal of Cancer and Clinical Oncology, 25(3), 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JFR, Willsher PC, Winterbottom L, Blamey RW & Thorpe S (1999) Onapristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, as first-line therapy in primary breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer, 35(2), 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas PA, May M, Sequeira GR, Elia A, Alvarez M, Martinez P, Gonzalez P, Hewitt S, He X, Perou CM, et al. (2017) Progesterone Receptor Isoform Ratio: A Breast Cancer Prognostic and Predictive Factor for Antiprogestin Responsiveness. J Natl Cancer Inst, 109(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, Jackson RD, Beresford SA, Howard BV, Johnson KC, et al. (2002) Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. Jama, 288(3), 321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheschowitsch K, Leite JA & Assreuy J (2017) New Insights in Glucocorticoid Receptor Signaling-More Than Just a Ligand-Binding Receptor. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 8, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MP, O’Leary KA, Fakhraldeen SA, Goffin V, Friedl A, Wisinski KB, Alexander CM & Schuler LA (2018) Antiestrogen Therapy Increases Plasticity and Cancer Stemness of Prolactin-Induced ERalpha(+) Mammary Carcinomas. Cancer Res, 78(7), 1672–1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen T, Horwitz KB & Lange CA (2001) Transcriptional hyperactivity of human progesterone receptors is coupled to their ligand-dependent down-regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent phosphorylation of serine 294. Mol Cell Biol, 21(18), 6122–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal H, Greene ME, Zarnke AL, Laine M, Al Abosy R, Chang YF, Dembo AG, Schoenfelt K, Vadhi R, Qiu X, et al. (2018) Progesterone receptor isoforms, agonists and antagonists differentially reprogram estrogen signaling. Oncotarget, 9(4), 4282–4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sletten ET, Arnes M, Lysa LM, Larsen M & Orbo A (2019) Significance of progesterone receptors (PR-A and PR-B) expression as predictors for relapse after successful therapy of endometrial hyperplasia: a retrospective cohort study. Bjog, 126(7), 936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soini T, Hurskainen R, Grénman S, Mäenpää J, Paavonen J, Joensuu H & Pukkala E (2016) Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system and the risk of breast cancer: A nationwide cohort study. Acta Oncologica, 55(2), 188–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahn C & Buttgereit F (2008) Genomic and nongenomic effects of glucocorticoids. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol, 4(10), 525–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellato C, Porreca I, Cuomo D, Tarallo R, Nassa G & Ambrosino C (2016) The “busy life” of unliganded estrogen receptors. Proteomics, 16(2), 288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehl C, Ehlers L, Gaber T & Buttgereit F (2019) Glucocorticoids-All-Rounders Tackling the Versatile Players of the Immune System. Front Immunol, 10, 1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumbayev VV & Yasinska IM (2005) Regulation of MAP kinase-dependent apoptotic pathway: implication of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 436(2), 406–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanos T, Sflomos G, Echeverria PC, Ayyanan A, Gutierrez M, Delaloye JF, Raffoul W, Fiche M, Dougall W, Schneider P, et al. (2013) Progesterone/RANKL is a major regulatory axis in the human breast. Sci Transl Med, 5(182), 182ra55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirpe AA, Gulei D, Ciortea SM, Crivii C & Berindan-Neagoe I (2019) Hypoxia: Overview on Hypoxia-Mediated Mechanisms with a Focus on the Role of HIF Genes. Int J Mol Sci, 20(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong TH, Dwyer AR, Diep CH, Hu H, Hagen KM & Lange CA (2019) Phosphorylated Progesterone Receptor Isoforms Mediate Opposing Stem Cell and Proliferative Breast Cancer Cell Fates. Endocrinology, 160(2), 430–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong TH, Hu H, Temiz NA, Hagen KM, Girard BJ, Brady NJ, Schwertfeger KL, Lange CA & Ostrander JH (2018) Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes in ER(+) Breast Cancer Models Are Promoted by PELP1/AIB1 Complexes. Mol Cancer Res, 16(4), 707–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong TH & Lange CA (2018) Deciphering Steroid Receptor Crosstalk in Hormone-Driven Cancers. Endocrinology, 159(12), 3897–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsitoura DC & Rothman PB (2004) Enhancement of MEK/ERK signaling promotes glucocorticoid resistance in CD4+ T cells. J Clin Invest, 113(4), 619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JD & Muller CP (2005) Structure of the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1) gene 5′ untranslated region: identification, and tissue distribution of multiple new human exon 1, 35(2), 283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadlamudi RK, Wang RA, Mazumdar A, Kim Y, Shin J, Sahin A & Kumar R (2001) Molecular cloning and characterization of PELP1, a novel human coregulator of estrogen receptor alpha. J Biol Chem, 276(41), 38272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell SE, Narayanan R, Weigel NL & Edwards DP (2010) Partial Agonist Activity of the Progesterone Receptor Antagonist RU486 Mediated by an Amino-Terminal Domain Coactivator and Phosphorylation of Serine400. Molecular Endocrinology, 24(2), 335–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Chaudhuri S, Brickley DR, Pang D, Karrison T & Conzen SD (2004) Microarray analysis reveals glucocorticoid-regulated survival genes that are associated with inhibition of apoptosis in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res, 64(5), 1757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Wang S, Wang Y, Wu H, Frank JA, Zhang Z & Luo J (2018) Role of p38γ MAPK in regulation of EMT and cancer stem cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular basis of disease, 1864(11), 3605–3617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Ravindranathan P, Ramanan M, Kapur P, Hammes SR, Hsieh JT & Raj GV (2012) Central role for PELP1 in nonandrogenic activation of the androgen receptor in prostate cancer. Mol Endocrinol, 26(4), 550–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Beck CA, Poletti A, Clement J. P. t., Prendergast P, Yip TT, Hutchens TW, Edwards DP & Weigel NL (1997) Phosphorylation of human progesterone receptor by cyclin-dependent kinase 2 on three sites that are authentic basal phosphorylation sites in vivo. Mol Endocrinol, 11(6), 823–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]