Abstract

Mice have been excellent surrogates for studying neutrophil biology and, furthermore, murine models of human disease have provided fundamental insights into the roles of human neutrophils in innate immunity. The emergence of novel humanized mice and high-diversity mouse populations offers the research community innovative and powerful platforms for better understanding, respectively, the mechanisms by which human neutrophils drive pathogenicity, and how genetic differences underpin the variation in neutrophil biology observed among humans. Here, we review key examples of these new resources. Additionally, we provide an overview of advanced genetic engineering tools available to further improve such murine model systems, of sophisticated neutrophil-profiling technologies, and of multifunctional nanoparticle (NP)-based neutrophil-targeting strategies.

Keywords: neutrophils, NETs, NSG, patient-derived xenografts, neutrophil dermatoses, psoriasis, genetically diverse mice, CRISPR, site-specific recombinases

Teaser: Advanced genetic engineering tools, humanized PDX mice, recombinant inbred strains, and highly diverse outbred mice provide valuable opportunities for exploring new avenues in translational research on neutrophils.

Introduction

Neutrophils are phagocytes that facilitate phagosome formation by internalizing opsonized vacuoles, which are opsonin- or antibody-coated foreign particles, such as bacterial and fungal pathogens [1,2]. Following internalization of the vacuoles, phagosomes undergo a maturation process, whereby the newly internalized vacuoles are fused with enzyme-laden granules, initiating a chain of events commonly referred to as oxidative, or respiratory, burst [3]. This burst begins with the activation of membrane-bound NADPH oxidase, which rapidly catalyzes the reduction of molecular oxygen to large quantities of an intermediate superoxide anion (O2−), which is then converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by superoxide dismutase (SOD). Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a peroxidase enzyme most abundantly expressed in neutrophils, then catalyzes the conversion of H2O2 into hypochlorous acid (HClO), which is effective at degrading pathogens engulfed by neutrophils [4]. Subsequently, degraded pathogens are released as antigens into the extracellular space through a process known as exocytosis [5]. An alternative to phagocytosis as a host-defense process is degranulation. In contrast to phagocytosis, through which engulfed pathogens are degraded inside neutrophils, degranulation involves fusion of granules with the plasma membrane of neutrophils and the subsequent extracellular release of granule contents. Release of the granule contents, including MPO, neutrophil elastase (NE), and cathepsin G, from primary or azurophilic granules; NADPH oxidase, lactoferrin (LTF), lysozyme, and cathelicidin antimicrobial peptides from secondary granules; and cathepsin and metalloproteinases from tertiary granules, disrupts microbial biofilms and contributes to host defense [6–8]. In addition to phagocytosis and degranulation, neutrophils kill bacteria and other microbes through formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), a process commonly known as NETosis [9,10]. NETosis involves nuclear and plasma membrane disruption and the release of decondensed chromatin fibers encircled with histones and granule enzymes, including MPO, NE, LTF, matrix metallopeptidase 9 (MMP-9), cathelicidin (LL-37), and proteinase 3 (PR3), into the extracellular space at the site of infection. Although the specific mechanisms underlying NETosis are still emerging, substantial literature suggests that NETosis is mediated either through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent or ROS-independent mechanisms, depending on the nature of the stimulus [11–13]. The mechanisms underlying the chromatin decondensation and nuclear and plasma membrane disruption that occur during NETosis are ill-defined. Loss-of-function studies in mice and in vitro pharmacological inhibition assays indicate that peptidylarginine deiminase type IV (PADi4)-mediated citrullination (conversion of the amino acid arginine into citrulline) of histones H2A, H3, and H4 might have a direct role in the chromatin decondensation occurring during NETosis. Subsequently, chromatin fibers carrying neutrophil granule enzymes and antimicrobial peptides on their surfaces are released extracellularly, where they capture and degrade pathogens. Neutrophils also have the ability to orchestrate both innate and adaptive immune responses [14]; during infection, neutrophils rapidly accumulate in abundant numbers and mediate immune modulation through interaction with T- and B-lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, platelets, monocytes/macrophages, and dendritic cells to efficiently eliminate foreign pathogens [15–18].

Thus, neutrophils have a protective role by participating in host, immunity to bacterial pathogens. Correspondingly, impairment of neutrophil function often results in immune dysregulation, a common feature of primary immunodeficiency disorders and inherited chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). CGD results from inactivating autosomal recessive mutations in NADPH oxidase, which is essential for ROS generation and microbicidal activity of neutrophils [19]. In addition, leukocyte adhesion deficiency-1 (LAD1), an autosomal recessive immunodeficiency, results from mutations in the ITGB2 gene, which encodes CD18, a protein essential for the adhesion of neutrophils to the endothelium and microbes [20]. In LAD1, neutrophils fail to migrate to the sites of infection and inflammation, thus increasing susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections. Furthermore, other aspects of neutrophil dysfunction have a role in both rare and common diseases, including neutrophilic dermatoses, hidradenitis suppurativa, psoriasis, and cancer, as described in detail later.

Neutrophils in inflammation

Neutrophils have a pivotal role in host immune processes, and their dysregulation can lead to a variety of pathologies. Here, we discuss the role of neutrophils in inflammatory disorders, with a particular focus on skin conditions. These conditions illustrate the importance of neutrophil function and the many ways through which defects in genes associated with neutrophil function can precipitate in both rare and common diseases.

Neutrophilic dermatoses

Neutrophilic dermatoses (NDs) encompass a heterogenous group of polygenic neutrophil-mediated inflammatory diseases, including pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), Sweet’s syndrome (SS), rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH), generalized pustular psoriasis, and Behçet, disease, all of which are characterized by reoccurring periods of tissue inflammation and significant infiltration of hyperactive neutrophils in all three layers of the skin (epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis) [21–24]. Here, we briefly review the role of intracellular signaling pathways in neutrophils in the pathogenesis of NDs in three mouse models of Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP1) deficiency. SHP-1, encoded by Ptpn6, is an important negative regulator of signaling pathways in neutrophils. Three spontaneous mutations in Ptpn6 [the motheaten (me) [25], viable motheaten (mev) [26], and spontaneous inflammation (spin) [27] mutations] have been crucial in our understanding of SHP-1 function in the development of inflammatory skin diseases that exhibit histopathological and clinical features similar to those of NDs in humans. Studies using Ptpn6spin mice showed that dysregulated SHP-1 activity in neutrophils results in cutaneous inflammation via receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP 1)-regulatecl IL-1α secretion, but not via inflammasome or IL-1β signaling [28,29]. Additionally, loss of either interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R) or the innate immune signal transduction adaptor MyD88 protected Ptpn6spin mice from NDs, suggesting that IL-1α acting through IL-1R and MyD88 drives inflammation in these mice [30]. Additional studies in Ptpn6spin mice suggest that several kinases, including spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), and apoptosis signal-regulating kinases 1 and 2 (ASK1 and ASK2), are crucial mediators of cutaneous inflammatory disease [31]. Recently, a study using genetic ablation in Ptpn6spin mice showed that caspase-associated recruitment of domain 9 (CARD9), an essential mediator of innate immune responses from SYK to the nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway in response to several intracellular pathogens, is a crucial mediator of cutaneous inflammation in these mice [32]. Together, these studies suggest that intrinsic defects in neutrophils are sufficient to drive disease pathogenesis in NDs.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with several concomitant, processes occurring in the skin, immune system, and skin microbiome. Recent evidence points to a role of defective keratinocyte function as a trigger of pathogenesis. To determine whether intrinsic defects in keratinocyte function underlie HS pathogenesis, Jones et al. [33] examined differences between the keratinocytes of healthy individuals and those of individuals with HS and reported that normal keratinocytes are capable of producing IL-22, an IL-10 family cytokine that is produced primarily by hematopoietic cells [T helper (Th)-17 cells, NK T (NKT) cells, and innate lymphoid cells] and that HS keratinocytes produced significantly lower amounts of IL-22 compared with controls. Importantly, the authors demonstrated that lower amounts of IL-22 were not attributable to lower keratinocyte viability or increased apoptosis of HS keratinocytes, because there were no significant differences in viability or apoptosis between HS and normal keratinocytes. These results suggest that a defective IL-22 signaling pathway in keratinocytes underlies HS pathogenesis. Additionally, in vitro, small hairpin RNA (shRNA)-mediated knockdown of NCSTN, which encodes a component of the gamma (γ)-secretase complex, in a keratinocyte cell line resulted in a transcriptional profile similar to the inflammatory type I interferon (IFN) signature commonly observed in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjögren’s syndrome [34,35], possibly through the Notch and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathways [36], indicating that keratinocytes are capable of a strong inflammatory response because of inherent defects in γ-secretase activity. Consistently, keratinocytes isolated from patients with HS elicit a proinflammatory phenotype (i.e., upregulated expression of components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, activated caspase-1, and expression of S100A8/S100A9) [37,38], suggesting that keratinocytes trigger and sustain chronic inflammation in the skin. Nevertheless, although substantial literature, as described earlier, indicates that intrinsic defects in keratinocytes are sufficient to drive HS pathogenesis, emerging literature suggests that HS is also a cutaneous presentation of a systemic neutrophilic condition; neutrophils, specifically NETs, have a key role in immune dysregulation in HS [39], and HS comorbidities include ND disorders, such as PG, Behçet, disease, SS, and NEH [40–42], warranting a more inclusive evaluation of the role of neutrophil-intrinsic mechanisms in HS pathogenesis.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease skin disease affecting millions of people worldwide. Disease initiation and progression proceed through both neutrophil-associated and -independent mechanisms. For instance, enhanced infiltration of neutrophils has been proposed to trigger psoriasis [43–47]. Multiple lines of evidence support this notion. First, there is abundant infiltration of neutrophils in the psoriatic skin [48–51]. Second, in vivo models of human skin inflammation (leukotriene B4 application and tape-stripping) show that most IL-17 is produced by neutrophils infiltrating the inflamed skin [52]; IL-17 is a proinflammatory cytokine that is involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, and antibodies targeting IL-17 have shown promising results in human clinical trials [53–56]. In addition to IL-17, neutrophils co-express the IL-17-associated transcription factor retinoid acid receptor-related orphan receptor gamma t, (RORγt), suggesting that sustained infiltration of an IL-17+ RORγt+ double-positive neutrophil population leads to psoriasis pathogenesis [52]. Third, although IL-17/1L-22 dual-secreting Th17 cells have been implicated in the pathophysiology of psoriasis [57], a recent RNA-seq analysis of human normal and psoriasis lesional skin failed to identify dual-secreting Th17 T cells, suggesting alternative sources of IL-17 and IL-22 [58]. Fourth, in the imiquimod (IMQ)-induced mouse model of psoriasis, anti-Ly6G monoclonal antibody-mediated depletion of neutrophils alone considerably ameliorated disease severity through a reduction in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines [47]. Lastly, in a rare type of psoriasis, generalized pustular psoriasis, neutrophils in the patients’ skin elicit, enhanced secretion of exosomes that were subsequently internalized by keratinocytes, leading to an immunomodulatory effect on keratinocytes through activation of the NFκB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways, and thereby to increased expression of proinflammatory genes, such as that encoding tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and IL1b and IL18 [46].

Recent studies suggest that intrinsic defects in keratinocytes initiate psoriasis [59–61]. In humans, autosomal dominant mutations in the keratinocyte signaling molecule caspase recruitment domain family member 14 (CARD14) increase susceptibility to psoriasis. Correspondingly, Card14 mutant mice (Card14E138A/+ mice and Card14DQ136+ mice) spontaneously develop a psoriasis phenotype via activation of the 1L-17A signaling pathway, whereas Card14 knockout, (KO) mice show resistance to psoriasis [60]. Moreover, in vitro experiments demonstrated that intrinsic defects in keratinocytes alone can trigger a psoriasis-like inflammatory phenotype; isolation of keratinocytes from Card14E138A/+ mutant pups and Card14+/+ pups followed by stimulation of the keratinocytes with IL-17A resulted in higher transcript levels of chemokine ligand 20 (Ccl20), S100a8, and S100a9, the expression of which promoted inflammation through activation of the NFκB pathway in the mutant compared with the wild-type keratinocytes [61]. These results suggest that intrinsic defects in keratinocytes alone underlie the psoriasis phenotype observed in Card14 mutant mice [60,61]. Collectively, these studies indicate that complex interactions among neutrophils, lymphocytes, and keratinocytes drive disease pathogenesis in psoriasis.

Neutrophils in cancer

Substantial evidence indicates that neutrophils elicit both protumorigenic and anti-tumorigenic/antimetastatic activity. The contrasting roles of neutrophils can be attributed in part to the ability of tumors to manipulate the normal development and cytotoxic function of neutrophils, resulting in initiation, progression, or suppression of tumor growth, or metastasis [62–67]. In both humans and mice, several factors, including transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), MMPs, and type I IFNs, have been shown to polarize tumor-associated neutrophils to either a protumor or an anti-tumor phenotype [68–75].

Tumor-secreted factors influence neutrophil-mediated protumor activity. For instance, using a mouse model of breast, cancer, Casbon et al. showed that sustained production of tumor-derived granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) suppressed erythropoiesis and increased myelopoiesis in the bone marrow, thereby expanding the number of immunosuppressive neutrophils [76]. Likewise, in mouse models of spontaneous breast cancer metastasis, Coffelt and colleagues found that tumors, via IL-1β-mediated expression of IL-17 from gamma delta (γδ) T cells and production of G-CSF by γδ T cells, polarized neutrophils to suppress cytotoxic T cell activity, promoting metastases [77]. Similarly, in mouse models of lung cancer, Faget et al. found that cancer cells expressed the zinc-finger transcription factor Snail, resulting in enhanced intratumoral secretion of the chemokine CXCL2, which in turn enhanced neutrophil infiltration while reducing T-lymphocyte homing [70]. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that depletion of neutrophils resulted in reduced lung tumor growth by enriching effector T-lymphocyte homing. More recently, Raccosta and colleagues showed that freshly isolated human tumor cells secreted liver X receptor ligands, (i.e., oxysterols, which are oxygenated derivatives of cholesterol) and recruited tumorigenic neutrophils in a chemokine receptor (CXCR2)-dependent manner to promote angiogenesis and immunosuppression [78]. Also, in mouse models of inflammation and spontaneous tumorigenesis, and in human pancreatic cancer, inhibition of tumor-derived chemokines via activation of CXCR2 prevented the infiltration of protumorigenic neutrophils, thus hindering tumor growth and metastasis [79,80].

Interestingly, tumor-secreted factors also influence neutrophil-mediated anti-tumorigenic/antimetastatic activity. In mouse models of breast, cancer, Granot, and colleagues showed that the tumor-secreted chemokine CCL2 activated neutrophils to secrete H2O2, which in turn triggered a calcium-permeable, H2O2-sensitive TRPM2 channel on tumor cells, inducing neutrophil-mediated cytotoxicity and preventing metastatic seeding of tumor cells in the lungs [81,82]. More recently, neutrophils were shown to mediate antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) by a novel mechanism known as trogoptosis [83]; Matlung et al. demonstrated that, independent of phagocytosis and degranulation, neutrophils conjugate with antibody-opsonized tumor cells to destroy them via the integrin CD11b/CD18 [84]. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that inhibition of conjugate formation between neutrophils and tumor cells with anti-CD11b and anti-CD18 antibodies, or both together, completely abolished neutrophil-mediated ADCC.

Neutrophils accordingly respond to tumor-secreted factors by exhibiting a high degree of functional plasticity, enabling them to orchestrate either protumoral or anti-tumoral immune responses. For example, in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma, Houghton et al. found that a serine proteinase secreted by neutrophils, neutrophil elastase, accelerated tumor cell proliferation by promoting enhanced interaction between PI3K and the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) [85]. Additionally, several studies have shown that activated neutrophils produce nitric oxide, hypochlorous acid (HOC1), IFNγ, TNFα, Fas ligand, CXCL1, and soluble TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) to kill tumor cells [86–89]. By contrast, neutrophil-derived TGF-β, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-16, CXCL8, oncostatin M, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transferrin (an iron-binding blood plasma glycoprotein), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), and arginase I promote neutrophil-mediated immunosuppression, carcinogenesis, and metastatic tumor-cell seeding [89–94].

Collectively, these studies demonstrate a crucial role of neutrophils in the tumor microenvironment, offering challenges and therapeutic opportunities for manipulating neutrophils in cancer. Here, we discuss how next-generation mouse models and genetic engineering technologies can assist in investigating the crucial role of human-specific tumor-derived or neutrophil-produced growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines in promoting tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis.

Next-generation mouse models for the study of human neutrophils

Severely immunodeficient Il2rgnull mice for optimal engraftment of human neutrophils

Humanized murine models (severely immunodeficient mice engrafted with functional human hematopoietic cells, immune cells, and/or tissues) are valuable preclinical in vivo systems for studying human disease pathology and testing novel human biologies. The strains most commonly used for development of humanized mice [95,96] [C;129S4-Rag2tm1FlvIl2rgtm1Flv (BRG), NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG), and NODShi.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Sug (NOG)] carry a mutation in either Rag2 or Prkdc, preventing the development of mature T and B cells; as well as a mutation in the IL-2 receptor common γ-chain (Il2rg) locus, which is shared by receptors for IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21, preventing the development of mature mouse NK cells [97–100]. Over the past 10 years, advances in our understanding of the human hematopoietic cytokines and growth factors needed to support engraftment of the human immune system have resulted in the development of novel strains based on the NSG mouse platform, including NSG-Tg(hu-mSCF) mice, which express human membrane-bound stem cell factor (SCF) [101–103], and NSG-SGM3 mice, which are triple transgenic mice that constitutively produce human SCF, granulocyte/macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and IL-3 [104]. These next-generation NSG models (Figure 1A) support heightened expansion of human neutrophils [103,105], providing superior in vivo environments that mimic the natural human environment more closely than is possible in previously available mouse models, enabling studies focused on the role of neutrophils in human inflammatory diseases. In addition, a novel strain of hemolytic complement (Hc)-sufficient NSG mice (NSG-Hc) [106] supports studies of complement-mediated as well as complement-independent activity of antibody-based biologies.

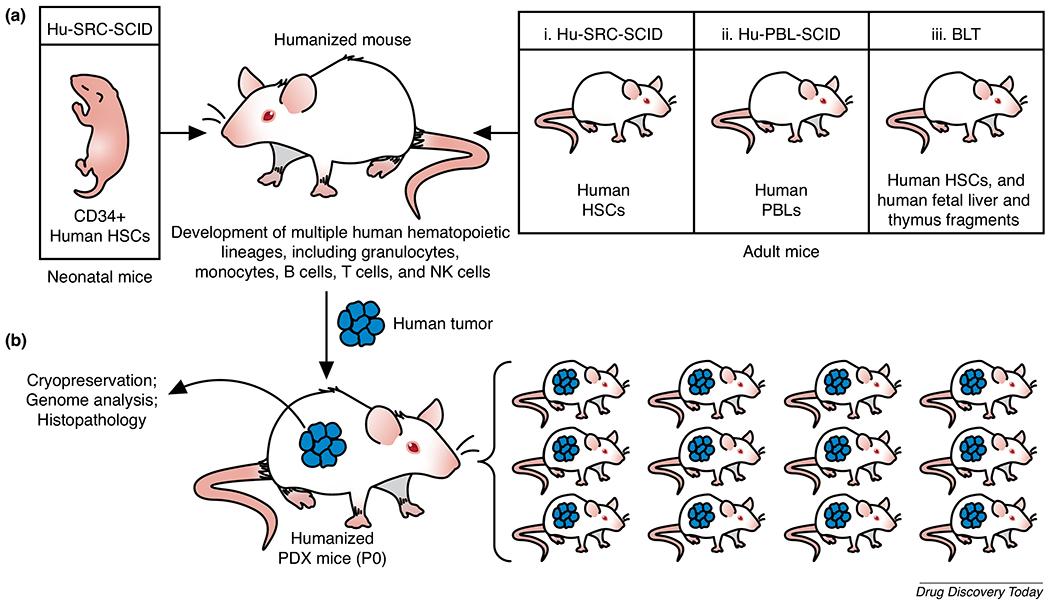

Figure 1.

(a) Humanization of immunodeficient IL-2 receptor common γ-chain (Il2rg)null mice can be achieved by generating the (i) Hu-SRC-SCID model, through injection of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) obtained from bone marrow, or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)-mobilized peripheral blood, or fetal liver, or umbilical cord blood, into newborn or adult NSG mice, which results in the development of a complete functional human immune system; (ii) Hu-PBL-SCID model, through injection of human peripheral blood leukocytes (PBLs) into adult NSG mice, which results in engraftment and expansion of human T cells within one week. While engrafted mice succumb to xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) within 4–8 weeks, lack of murine major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I or class II molecules can significantly delay GVHD development; or (iii) bone marrow/liver/thymus (BLT) model, through transplantation of fragments of human fetal liver and thymus under the kidney capsule, followed by intravenous injection of autologous fetal liver CD34+ HSCs. (b) Patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models: PDX models are generated by implanting patient-derived tumors in severely immunodeficient NSG mice. Utilizing humanized mice for human tumor implantation enables the study of human tumor–immune cell interactions and the testing of immunotherapies. Abbreviation: NK cells, natural killer cells.

Patient-derived xenograft mice

Severely immunodeficient mice that have been implanted with human tumor tissues and/or cells are commonly referred to as patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mice [107]. These mice, when engrafted with functional human HSCs and immune cells, provide a superior preclinical platform to study human immune cell infiltration of the primary tumor, evaluate tumor–immune interactions, and test existing, new, and combinatorial therapies (Figure 1B). Notably, to a great extent, human tumors in these mice maintain the molecular and genomic characteristics of the primary patient tumor and, thus, engraftment, of pieces of a tumor (P0) in a cohort of mice enables preclinical trials with sufficient statistical power to test tailored therapies. For detailed protocols on creating humanized PDX mice, see [108].

PDX mice have been used to evaluate the role of human neutrophils at metastatic sites and the efficacy of therapeutic antibody treatment in regulating the numbers of human neutrophils at these sites. For instance, Ngo and colleagues examined how antibody-mediated blocking of CD47, an antiphagocytic signal on melanoma cells, suppresses melanoma metastasis in PDX mice, observing that CD47 blockade, but not nonspecific IgG-blockade (control group), resulted in a significant reduction in the numbers of prometastatic neutrophils in the lungs [109]. More recently, to identify the mechanisms underlying the non-metastatic behavior of certain breast cancers, Hagerling et al. utilized a PDX model of breast cancer and found that the primary breast tumors secrete CCL2, resulting in recruitment of proinflammatory cytokine (IFNγ and TNFα)-producing monocytes from the bone marrow to the lungs, a frequent, site of metastases. Furthermore, it, was shown in the lungs that, whereas IFNγ upregulates Tmem173, a gene encoding STING (a key player in host defense) to enhance the killing capacity of neutrophils, TNFα exhibits a direct, tumoricidal activity [110]. These studies and many others clearly demonstrate that PDX models are a powerful translational research tool for studying and developing therapeutics designed to modulate neutrophil activity in inflammation and cancer.

Genetic engineering technologies for generating clinically relevant mouse models

Although the NSG strain and novel NSG-based strains support improved engraftment, of myeloid cells, there is a constant requirement to identify mouse cytokines and growth factors that do not fully support human myeloid development and replace them with human-specific factors. Human-specific growth factors can be provided by somatic gene therapy via lentiviral or adeno-associated virus (AAV) [111,112], hydrodynamic injection of DNA [113], and injection of recombinant proteins [114], or by germline modification, using random transgenesis and/or transgenic overexpression [115,116]. Although these approaches have significantly improved the development and function of engrafted human cells, they have striking limitations: lentiviral expression can result in nonphysiological concentration of cytokines; injection of DNA or recombinant, protein is labor intensive; the expression of cytokines can be transient, leading to ineffective maintenance of engrafted human cells; and germline modification involving random integration of transgenes can be a confounding factor, because it can disrupt endogenous coding sequences and insert undocumented cassettes or contaminating DNA fragments, ultimately resulting in possible phenotypic changes [117]. The more targeted and direct germline genetic engineering approaches that have recently emerged [e.g., knock-in strategies inserting a Cre transgene and a fluorescent reporter tag into the mouse endogenous neutrophil-specific locus Ly6G [118]] enable Cre-mediated recombination of floxed alleles specifically in neutrophils, and live cell imaging and tracking of neutrophils, respectively.

Additionally, knock-in strategies replacing mouse genes with those of humans have many advantages, including the capacity to maintain physiological amounts of cytokines; reduced amount of labor required compared with the other currently used methods; and an absence of competition between mouse and human factors for binding to the same receptors. Nevertheless, the knock-in strategy using a conventional gene-targeting method [i.e., homologous recombination in embryonic stem (ES) cells] can be time-consuming [119]. A more direct approach of using CRISPR/Cas9-directed homology-directed repair (HDR) insertion of transgenes has been successful in integrating alleles that are ~0.5–2.5-kb long; however, there have been no reports of efficient targeted transgenesis of large mouse DNA fragments that are >3 kb or more in length, excluding the homology arms [120–127]. Thus, an efficient and reliable method for insertion of large transgenes with appropriate expression is urgently needed. With this in mind, new approaches allowing precise insertion of large transgene constructs, such as site-specific serine recombinases for targeted transgenesis [128–130], are being considered.

Site-specific serine recombinases for targeted modification of the mammalian genome

Serine recombinases, such as phiC31 integrase, utilize specific ~50-bp DNA attachment sites (attP and its cognate site attB) as substrates for efficient precision transgenesis. Tasic et al. showed that, in an FVB background, the phiC31 integrase catalyzes recombination between an attB site in recombinant DNA (plasmid or minicircle) and an attP site prepositioned in the Rosa26 locus in the mouse genome at 40% efficiency with a 3-kb DNA fragment [131]. However, this study relied on placement of the cognate attP site in 129 F1 ES cells via homologous recombination, and the resulting founder mice were backcrossed on to B6D2 F1 mice, generating mice on a mixed genetic background, which can give confounding results [132,133]. With the advent of CRISPR/Cas9-meditated HDR directly in zygotes, the site-specific recombinase approach can now be re-evaluated to enable direct introduction of attP attachment sites into the Rosa26 locus or any predetermined loci in any inbred mouse strain. This can be followed by precise recombination of donor DNA carrying the cognate attB site. A similar system has begun to be applied to various inbred mouse strains, including NSG, obtaining rates of transgene insertion at ~30% with constructs ranging from 2 to 30 kb (M.V.W., unpublished observations, 2020) (Figure 2). While site-specific serine recombinases could overcome the problem of random integration when using most existing approaches for integration of large DNA constructs, random integration of transgenes into pseudo-sites (endogenous sites in the mammalian chromosome that resemble attP and attB attachment sites) is a possibility. The use of various screening approaches, including long-range PCR, whole-genome sequencing, and backcrossing founder mice (F0) mice to wild-type mice, can help to eliminate any such random off-target events observed.

Figure 2.

Knock-in of large transgenes into the mouse genome using site-specific recombinases: phiC31 integrase utilizes the ~50-bp DNA attachment sites attP and attB to integrate exogenous DNA. Use of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated oligonucleotide homology-directed repair (HDR) placement of the attachment site attP (e.g., attP selectively placed in the Rosa26 locus) using electroporation into NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) zygotes (Step 1), followed by the use of a site-specific serine integrase phiC31 mRNA and donor DNA plasmid or minicircle (transgene) containing the attachment site attB can mediate highly efficient recombination between the attP and attB sequences to catalyze efficient precision transgenesis of large donor constructs (Step 2). Successful recombination results in irreversible unidirectional insertion of the transgene, flanked by attL (left) and attR (right) sites. Abbreviation: sgRNA, small guide RNA.

Harnessing genetically diverse mice to explore quantitative variation in neutrophil function

In addition to the use of humanized mouse models, an independent yet complementary approach for studying neutrophil function is to leverage genetic variation among mouse strains to better understand the genetic architecture of neutrophil-related traits. Novel mouse diversity resources present a unique opportunity to augment our understanding of neutrophil biology in a manner that is unbiased and allows access to polygenic networks (for a detailed review of mouse diversity resources from a phenotype-agnostic perspective, see [134]). The past several decades have seen the development of increasingly sophisticated mouse genetic mapping resources, including recombinant advanced intercross lines and outbred populations with defined genetic contributions from a set of inbred parental strains. Here, we focus on three mouse diversity resources that are of broad utility and have complementary strengths. The Collaborative Cross (CC) resource is a set of recombinant advanced inbred lines constructed by using a funnel breeding scheme to mate inbred mice from eight founder strains: five classical inbred and three wild-derived inbred strains [135,136] (Figure 3). The BXD resource comprises a panel of recombinant inbred (RI) lines derived from two parental strains, C57BL/6J and DBA/2J [137]. Existing BXD RI lines were produced by both standard F2 and advanced intercross strategies; thanks to several expansion efforts, the set of available lines now numbers 150 [138]. Lastly, Diversity Outbred (DO) mice constitute a heterogeneous stock derived from the same eight founder strains as those in the CC resource [139] (Figure 3). These three mouse diversity resources present valuable tools for the interrogation of neutrophil biology, and have both shared and distinct strengths. The BXD resource is supported by a vast catalog of organismal and molecular phenotypes that have been collected during decades of study in these strains [140]; phenotypes available for CC and DO mice are more limited, but have increased rapidly in volume and scope in recent years [141]. Each DO mouse is genetically unique and cannot be replicated, while CC and BXD mice are inbred and can be phenotyped multiple times. CC and DO mice segregate substantially more genetic variation than do BXD mice, likely driving increased phenotypic variation for traits of interest. Genetic mapping resolution in DO mouse studies is unparalleled for this organism, and is continually improving as ongoing breeding introduces recombination events and reduces the size of haplotype blocks [142].

Figure 3.

The Collaborative Cross (CC) recombinant inbred mouse strains are generated by an eight-way funnel breeding design involving eight genetically diverse parental inbred strains, which include five common laboratory strains (A/J, C57BL/6J, 129S1/SvImJ, NOD/ShiLtJ, and NZO/HiLtJ) and three wild-derived strains (CAST/EiJ, PWK/PhJ, and WSB/EiJ). The Diversity Outbred (DO) mouse population is derived from the same eight parental inbred strains. Whereas CC mice are recombinant inbred strains and can be phenotyped multiple times, DO mice are genetically unique and cannot be replicated.

Investigation of immunophenotypes relevant to neutrophil biology using these diverse mouse resources has been less extensive than the investigation of this aspect of neutrophil biology using classical inbred mouse strains. However, the use of genetically diverse mice in several studies has revealed important new information on neutrophil biology and the underlying genetic factors. One study measured blood neutrophil counts in 742 DO mice as a model quantitative trait, demonstrated that this trait is heritable, and detected a quantitative trait locus (QTL) containing a strong candidate gene (Cxcr4) that had previously been implicated in neutrophil release from the bone marrow [142]. Kelada et al. [143] observed similar quantitative variation in neutrophil counts in an early incarnation of the CC (pre-CC). A recent study measured 18 spleen immunophenotypes in >60 CC strains, identifying pervasive variation and QTLs for several of these phenotypes [144]. Although these two studies provided potentially important information on neutrophil biology and genetics, they are associated with an important caveat related to the use of flow cytometry, which was used for the neutrophil counts. Specifically, many commonly used cell surface markers were developed in a small number of inbred strains, and little is known about how reliably such markers translate to highly genetically diverse strains carrying polymorphisms affecting gene regulation and protein sequences. A few studies have focused on using diverse mice to study genetic drivers of allergic and infectious diseases. Ferris et al. [145] studied influenza A virus infection in the pre-CC, finding that neutrophil recruitment to the airway varied among these diverse strains. These authors identified a QTL that could be narrowed to 91 kb containing 12 genes and two noncoding RNAs [145], each of which is a candidate factor that might be involved in neutrophil recruitment post-infection. Rutledge et al. [146] focused on the role of miRNAs in allergic airway disease, using CC mice to identify candidate miRNAs that regulate suites of genes associated with neutrophil recruitment. In all the above cases, phenotypic variation was distributed along a continuum as opposed to discrete classes, which is characteristic of a quantitative trait controlled by variation in a large number of genes [147] and suggests genetic mapping as a strategy for the unbiased identification of loci harboring genetic variation contributing to phenotypic variation. Genetically diverse mice may also prove to be useful in the search for better models of neutrophil-related conditions. While there are no reports of novel mouse models in the area of neutrophil-mediated disease, one illustrative example is the finding that a CC strain (i.e., strain CC011/Unc) develops spontaneous colitis [148]. This model was identified during routine colony maintenance [148], but one might expect in general that informative models of immune-mediated diseases will be most efficiently identified by applying a perturbation of interest and measuring a quantitative response across a panel of diverse strains.

New technologies for profiling molecular and functional heterogeneity of neutrophils

Although it, has been recognized for some time that neutrophils have the capacity to carry out, their pathogen-destroying responsibilities by a variety of diverse mechanisms, as described earlier, the heterogeneity of neutrophils has only recently received significant, attention [149–154]. The lack of focus on neutrophil heterogeneity has been due, in part, to a relative lack of reliable surface markers delineating subgroups [155], and to their unique biological characteristics, including a short, lifespan [156]. Nevertheless, the functional diversity of neutrophils implies that distinct genetic programs drive the variable mechanisms by which these cells attack pathogens. Understanding the molecular drivers of neutrophil heterogeneity, and connecting molecular to functional heterogeneity, is an important goal for developing therapies to target neutrophil dysregulation, and for interpreting genetic variation within patient populations in light of its effect on neutrophil biology. Sophisticated profiling technologies, driven by advances in instrumentation, computation, and molecular biology, will have a key role in investigations of neutrophil heterogeneity.

The tight association between advances in flow cytometry technologies and immunological knowledge [157] is likely to continue, with the ever more detailed study of precisely defined cell subsets enabled by sophisticated variations on this versatile technology. Mass cytometry constitutes an important technology pushing the boundaries of cytometry by enabling the simultaneous quantification of up to ~40 cell surface proteins using antibodies conjugated to heavy-metal isotopes that are detected by mass spectrometry [158]. Although mass cytometry has unparalleled throughput and precision, it, is subject to the universal limitation of flow cytometry: the requirement, for a priori decisions about which proteins to measure, and the restriction to those proteins present on the cell surface. By contrast, there has been a recent explosion of interest in single-cell functional genomics technologies [159,160], several of which are now available commercially (e.g., 10X Genomics, Takara iCELL8, Fluidigm, and 1CellBio inDrop), on a build-your-own-instrument, basis [161,162], or using standard laboratory equipment [163]. Although these instruments differ in their capabilities, they are most, commonly used to profile gene expression by RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) in single cells (scRNA-Seq). Recent, studies have opened the way for the interrogation of other molecular phenotypes in thousands of cells, such as chromatin accessibility [164], histone modifications [165], DNA methylation [166], and protein abundance [167]. In neutrophil biology, a few studies have characterized large numbers of neutrophils using scRNA-Seq and have detected transcriptional heterogeneity in homeostatic, inflammatory, and disease states [168,169].

scRNA-Seq is a transformational method because, in principle, it, is unbiased and provides access to all transcripts in the cell without, restriction to cell-surface markers. The capacity to profile thousands of genes in an unbiased manner has proven to be a powerful combination, allowing the discovery of novel cell subsets, marker genes, transcription factor activities, and gene regulatory networks [170], while permitting the interrogation of function by means of pathway enrichment, methods. Additionally, new technologies are enabling large-scale chemical screens at, single-cell resolution [171–173].

Although single-cell functional genomics technologies show great promise, several challenges remain for their widespread application to neutrophils and the biology of inflammation, including uncertainties about, the optimal methods for cell preparation, potential losses because of decreases in cell viability, and the expense of the methods (reviewed in [174]). We expect that, over time, costs will decrease as technologies mature and experimental challenges will be mitigated by ‘best-practice’ methodologies established by the scientific community. Furthermore, new technologies that provide novel insights will further augment, our understanding of neutrophil biology. For example, the nascent, field of spatial transcriptomics [175,176] will provide detailed information about, where in tissues neutrophil subsets are present, and with what, other cells they establish contact. In addition, new methods providing multimodal data on multiple aspects of the state of a cell, such as single-cell functional measurements with genomic profiling (e.g., [177,178]) of the transcriptome and biochemical activities [179], the transcriptome and DNA methylation [180], the transcriptome and chromatin accessibility [181], and the transcriptome and proteome [182,183], might, enable us to more directly link molecular events to cellular actions. Taken as a whole, the future is bright, for technology in neutrophil biology, because both cutting-edge methods and clever applications of increasingly accessible current, technologies are likely to reveal new avenues for therapeutic intervention in neutrophil-mediated diseases.

New therapeutic possibilities unlocked by nanoparticle-based targeted delivery strategies

NP drug-delivery systems, such as liposomes, albumin-bound NPs, polymeric NPs, molecular-targeted NPs, magnetic NPs, and dendrimers, can deliver many different types of payload, including proteins, nucleic acids, small drug molecules, antibiotics, and chemotherapy medication (e.g., paclitaxel; approved for treating lung, ovarian and breast, cancers), to numerous cell types in vitro and in vivo [184–186]. Substantial literature indicates that NP formulations can impact, the capacity to target neutrophils effectively. For instance, albumin-based NPs loaded with piceatannol (a naturally occurring anti-inflammatory hydroxylated analog of resveratrol), but not piceatannol administration alone, showed the ability to interrupt β2-integrin-mediated adhesion of activated neutrophils while simultaneously increasing the number of rolling neutrophils, which together reversed adhesion to venular endothelial cells and reduced inflammation [187]. The same study investigated the mechanism of uptake of albumin-based NPs using FcγRIII (CD16) KO mice, and showed that loss of the FcγRIII receptor resulted in a significant, reduction in NP uptake compared with wild-type mice, indicating that adherent, neutrophils internalize albumin-based NPs via Feγ receptors. In a separate study, the use of albumin-based NPs to target, activated neutrophils was expanded to include NPs generated using a doxorubicin (DOX)-conjugated pH switch based on either a pH-sensitive hydrazone bond to bovine-serum albumin (BSA) or a PH-insensitive amine bond to BSA (DOX-hyd-BSA or DOX-ab-BSA, respectively) [188]; DOX induces cell death by causing DNA damage, and the pH switch was used to test its effectiveness in the low pH cellular environment of activated neutrophils. In activated neutrophils, DOX cleavage and release was observed from DOX-hyd-BSA NPs but not from DOX-ab-BSA control NPs. Consistently, DOX-hyd-BSA NPs but, DOX-ab-BSA control NPs effectively induced neutrophil apoptosis, where reductions in the number of activated neutrophils and the levels of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were observed in mouse models of acute lung inflammation, sepsis, and ischemic stroke. More importantly, cardiac toxicity, a characteristic adverse event associated with DOX administration, was observed only in mice receiving free DOX, and not in mice receiving DOX-conjugated NPs. Collectively, these studies suggest that drugdoaded albumin-based NPs significantly reduce the number of activated infiltrating neutrophils and also suppress secretion of inflammatory cytokines, while sparing other immune cells.

The ability to target neutrophils at the site of inflammation via NP administration can provide considerable advantages compared with systemic delivery. For instance, an antipsoriatic cream, dithranol, is applied directly to the affected areas of the skin, but adverse reactions, including skin irritation at the site of administration, have been observed [189]. Transdermal NP delivery demonstrated the capacity to deliver a variety of compounds [190], and Sathe et al. showed that transdermal delivery of dithranol-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) in the IMQ-induced mouse model of psoriasis effectively reduced scaling, skin thickening, and erythema, suggesting a potentially safer mechanism for dithranol usage [191]. In another study, topical application of oleic acid encapsulated in NLCs in the presence of albumin [192], but, not, free oleic acid, suppressed neutrophil infiltration and also reduced the severity of skin inflammation, in a mouse model of leukotriene B4-induced skin inflammation [193]. Together, these studies suggest that transdermal delivery of drug-loaded NLCs provides a greater benefit, for direct, targeting of activated neutrophils.

Concluding remarks

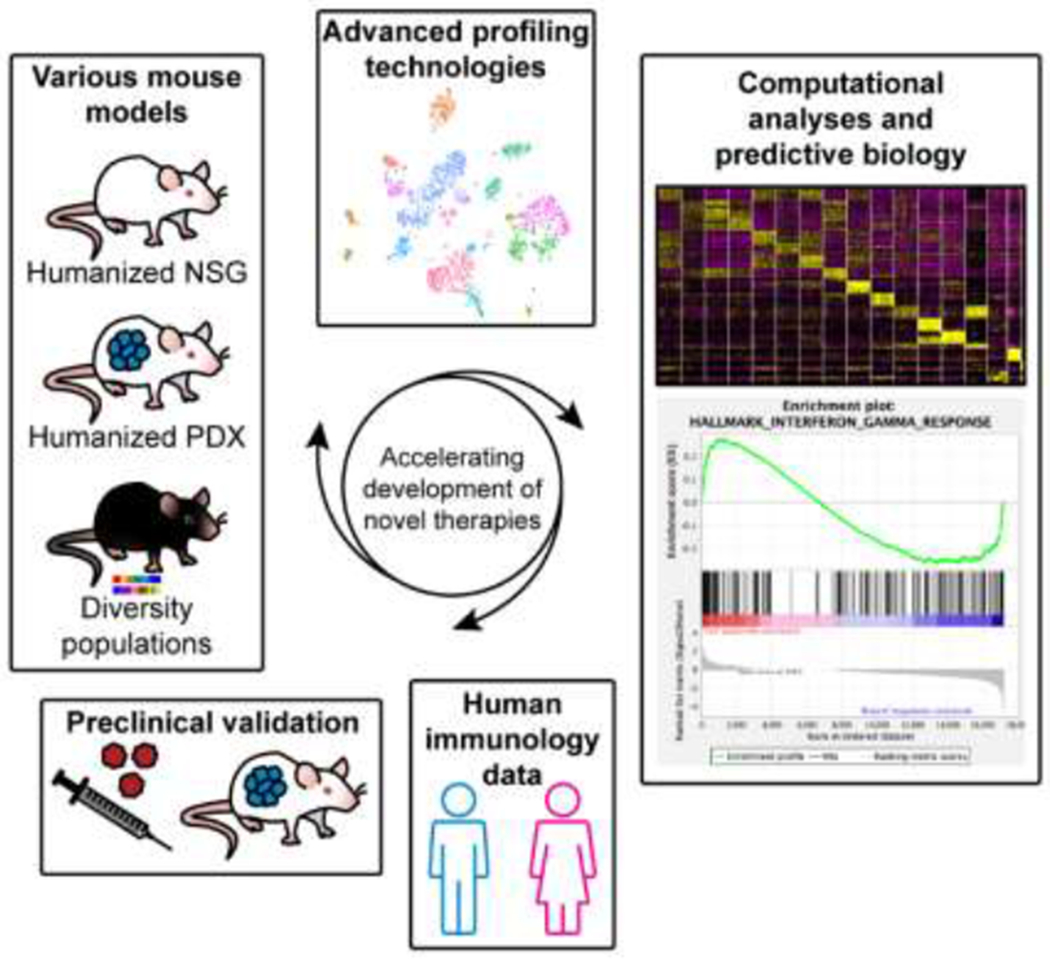

Neutrophils are highly heterogeneous granular leukocytes involved in the pathogenesis of diverse inflammatory diseases. The capacity to perform translational studies elucidating pathogenic mechanisms of neutrophils in orchestrating disease initiation and propagation has been significantly enhanced by recent, advances in the optimization of human hematopoiesis in severely immunodeficient, Il2rgnull mice, together with the availability of the genetically diverse CC, DO, and BXD mouse populations, in which neutrophil diversity closely mimics the genetic and phenotypic variability observed in human populations, and of PDX models, with their capacity for efficient, testing of novel cancer therapeutics. Moreover, optimized next-generation sequencing technologies, including scRNA-seq, to identify pathogenic neutrophil subsets, coupled with novel NP drug-delivery systems, represent, potentially effective translational strategies (Figure 4) for exquisitely precise therapeutics targeting neutrophils in complex inflammatory diseases and cancer.

Figure 4.

Mouse models of human disease continue to be invaluable tools for advancing our understanding of human immunology. Embracing new resources, such as humanized mice, patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mice, recombinant inbred strains, and highly diverse outbred mice, can overcome the limitations of either a lack of the genetic diversity that is observed in human populations, or a conducive environment for the study of human tumor–immune interactions. In addition, harnessing new genetic tools, such as site-specific recombinases for knock-in of large transgenes, single-cell technologies to profile the molecular and functional heterogeneity of neutrophils, and systems biology approaches, enables the rapid identification and development of novel therapeutic strategies for targeting of neutrophils in inflammation and cancer. Furthermore, the various mouse resources and the application of computational tools will be essential for testing hypotheses generated from large-scale human data sets. Abbreviations: NSG, NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ.

Table 1.

Select examples of NP-based strategies for neutrophil-targeting therapies

| NP system | Formulation composition | Incorporated drug | Animal model | Induced model | Transdermal delivery | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein NPs | BSA | Piceatannol | C57BL/6J, CD1, Mac-1−/−, LFA1−/−, and B6.129P2-Fcgr3tm1Jsv/J | N/A | No | [187] |

| Doxorubicin | C57BL/6 | N/A | No | [188] | ||

| CD1 mice: sepsis and lung Inflammation | Lipopolysaccharide | No | [188] | |||

| CD1 mice: ischemic stroke | Middle cerebral artery occlusion | |||||

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Trimystrin and Labrafac™ PG | Dithranol | BALB/c psoriasis model | Imiquimod | Yes | [191] |

| 6% Palmityl palpitates, 1% soy phosphatidylcholine, 6% oleic acid | Oleic acid | BALB/c | Leukotriene B4 | Yes | [193] |

Highlights.

The heterogeneity and diversity of neutrophils is important in a variety of diseases.

Humanized PDX mice is an important resource to gaining clinically relevant knowledge of neutrophils.

Three mouse diversity resources facilitate broad utility: the CC, DO, and BXD.

Site-specific recombinases can aid in generating next-generation mouse models.

Embracing novel mouse resources and harnessing new technologies, enables rapid development of novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stephen B. Sampson for critical reading of the manuscript, and Zoe Reifsnyder for help with graphics. Research reported in this publication was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30CA034196. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee WL et al. (2003) Phagocytosis by neutrophils. Microbes Infect. 5, 1299–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Kessel KP et al. (2014) Neutrophil-mediated phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Immunol 5, 467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lambeth JD (2004) NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol 4, 181–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pullar JM et al. (2000) Living with a killer: the effects of hypochlorous acid on mammalian cells. IUBMB Life 50, 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faurschou M and Borregaard N (2003) Neutrophil granules and secretory vesicles in inflammation. Microbes Infect. 5, 1317–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacy P (2006) Mechanisms of degranulation in neutrophils. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2, 98–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacy P and Eitzen G (2008) Control of granule exocytosis in neutrophils. Front. Biosci 13, 5559–5570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosales C (2018) Neutrophil: A Cell With Many Roles In Inflammation Or Several Cell Types? Front. Physiol 9, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkmann V et al. (2004) Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science 303, 1532–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee KH et al. (2017) Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. Autoimmun. Rev 16, 1160–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y et al. (2018) Neutrophil extracellular traps in autoimmune diseases. Chin. Med. J 131, 1513–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonaventura A et al. (2018) The pathophysiological role of neutrophil extracellular traps in inflammatory diseases. Thromb. Haemost 118, 6–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan MJ and Radic M (2012) Neutrophil extracellular traps: double-edged swords of innate immunity. J. Immunol 189, 2689–2695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leliefeld PH et al. (2015) How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Front. Immunol. 6, 471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prame Kumar K et al. (2018) Partners in crime: neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages in inflammation and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 371, 551–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scapini P and Cassatella MA (2014) Social networking of human neutrophils within the immune system. Blood 124, 710–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Herster F et al. (2019) Platelets aggregate with neutrophils and promote skin pathology in psoriasis. Front. Immunol 10, 1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diana J et al. (2013) Crosstalk between neutrophils, B-1a cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cells initiates autoimmune diabetes. Nat. Med 19,65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Segal BH et al. (2000) Genetic, biochemical, and clinical features of chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine 79, 170–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van de Vijver E et al. (2012) Hematologically important mutations: leukocyte adhesion deficiency (first update). Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 48, 53–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen PR (2009) Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol 10, 301–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salem I et al. (2019) Neutrophilic dermatoses and their implication in pathophysiology of asthma and other respiratory comorbidities: a narrative review. Biomed. Res. Int 2019, 7315274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marzano AV et al. (2018) A comprehensive review of neutrophilic diseases. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 54, 114–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson CA et al. (2018) Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behcet disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 79, 987–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green MC and Shultz LD (1975) Motheaten, an immunodeficient mutant of the mouse. I. Genetics and pathology. J. Hered 66, 250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shultz LD et al. (1984) ‘Viable motheaten,’ a new allele at the motheaten locus. I. Pathology. Am. J. Pathol 116, 179–192 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Croker BA et al. (2008) Inflammation and autoimmunity caused by a SHP1 mutation depend on IL-1, MyD88, and a microbial trigger. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 15028–15033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukens JR et al. (2013) RIP1-driven autoinflammation targets IL-1alpha independently of inflammasomes and RIP3. Nature 498, 224–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukens JR and Kanneganti TD (2014) SHP-1 and IL-1alpha conspire to provoke neutrophilic dermatoses. Rare Dis. 2, e27742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurung P et al. (2017) Tyrosine kinase SYK licenses MyD88 adaptor protein to instigate IL-1alpha-mediated inflammatory disease. Immunity 46, 635–648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tartey S et al. (2018) ASK1/2 signaling promotes inflammation in a mouse model of neutrophilic dermatosis. J. Clin. Invest 128, 2042–2047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tartey S et al. (2018) Cutting edge: dysregulated CARD9 signaling in neutrophils drives inflammation in a mouse model of neutrophilic dermatoses. J. Immunol 201, 1639–1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones D et al. (2018) Inherent differences in keratinocyte function in hidradenitis suppurativa: Evidence for the role of IL-22 in disease pathogenesis. Immunol. Invest 47, 57–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao L et al. (2019) Nicastrin haploinsufficiency alters expression of type I interferon-stimulated genes: the relationship to familial hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin. Exp. Dermatol 44, e118–e125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ronnblom L and Eloranta ML (2013) The interferon signature in autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol 25, 248–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao X et al. (2016) Nicastrin mutations in familial acne inversa impact keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation through the Notch and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT signalling pathways. Br. J. Dermatol 174, 522–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hotz C et al. (2016) Intrinsic defect in keratinocyte function leads to inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa. J. Invest. Dermatol 136, 1768–1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lima AL et al. (2016) Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Dermatol 174, 514–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Byrd AS et al. (2019) Neutrophil extracellular traps, B cells, and type I interferons contribute to immune dysregulation in hidradenitis suppurativa. Sci. Transl. Med 11, XXX–YYY [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fimmel S and Zouboulis CC (2010) Comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa). Dermatoendocrinology 2, 9–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller IM et al. (2016) Prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Clin 34, 7–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vekic DA and Cains GD (2017) Hidradenitis suppurativa - management, comorbidities and monitoring. Aust. Fam. Physician 46, 584–588 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katayama H (2018) Development of psoriasis by continuous neutrophil infiltration into the epidermis. Exp. Dermatol 27, 1084–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keijsers RR et al. (2014) Cellular sources of IL-17 in psoriasis: a paradigm shift? Exp. Dermatol 23, 799–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanda GE et al. (2017) Emerging associations between neutrophils, atherosclerosis, and psoriasis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep 19, 53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao S et al. (2019) Neutrophil exosomes enhance the skin autoinflammation in generalized pustular psoriasis via activating keratinocytes. FASEB J. 33, 6813–6828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sumida H et al. (2014) Interplay between CXCR2 and BLT1 facilitates neutrophil infiltration and resultant keratinocyte activation in a murine model of imiquimod-induced psoriasis. J. Immunol 192, 4361–4369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller M et al. (2005) T cell-regulated neutrophilic inflammation in autoinflammatory diseases. J. Immunol 175, 7678–7686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schaerli P et al. (2004) Characterization of human T cells that regulate neutrophilic skin inflammation. J. Immunol 173, 2151–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka N et al. (2000) Elafin is induced in epidermis in skin disorders with dermal neutrophilic infiltration: interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha stimulate its secretion in vitro. Br. J. Dermatol 143, 728–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zalewska A et al. (2004) Interleukin 4 plasma levels in psoriasis vulgaris patients. Med. Sci. Monit 10, Cr156–Cr162 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Keijsers R et al. (2014) In vivo induction of cutaneous inflammation results in the accumulation of extracellular trap-forming neutrophils expressing RORgammat and IL-17. J. Invest. Dermatol 134, 1276–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burkett PR and. Kuehroo VK. (2016) IL-17 blockade in psoriasis. Cell 167, 1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurschus FC and Moos S (2017) IL-17 for therapy. J. Dermatol. Sci 87, 221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malakouti M et al. (2015) The role of IL-17 in psoriasis. J. Dermatolog. Treat 26, 41–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silfvast-Kaiser A et al. (2019) Anti-IL17 therapies for psoriasis. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 19, 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liang SC et al. (2006) Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2271–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le ST et al. (2019) 2D Visualization of the psoriasis transcriptome fails to support the existence of dual-secreting IL-17A/IL-22 Th17 T cells. Front. Immunol 10, 589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mellett M et al. (2018) CARD14 gain-of-function mutation alone is sufficient to drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated psoriasiform skin inflammation in vivo. J. Invest. Dermatol 138, 2010–2023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka M et al. (2018) Essential role of CARD14 in murine experimental psoriasis. J. Immunol 200, 71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang M et al. (2018) Gain-of-function mutation of Card14 leads to spontaneous psoriasis-like skin inflammation through enhanced keratinocyte response to IL-17A. Immunity 49, 66–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coffelt SB et al. (2016) Neutrophils in cancer: neutral no more. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 431–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Piccard H et al. (2012) On the dual roles and polarized phenotypes of neutrophils in tumor development and progression. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol 82, 296–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fridlender ZG and Albelda SM (2012) Tumor-associated neutrophils: friend or foe? Carcinogenesis 33, 949–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dumitru CA et al. (2013) Modulation of neutrophil granulocytes in the tumor microenvironment: mechanisms and consequences for tumor progression. Semin. Cancer Biol. 23, 141–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shaul ME and Fridlender ZG (2019) Tumour-associated neutrophils in patients with cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 16, 601–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Granot Z (2019) Neutrophils as a therapeutic target in cancer. Front. Immunol 10, 1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sawanobori Y et al. (2008) Chemokine-mediated rapid turnover of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Blood 111, 5457–5466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Deryugina EI et al. (2014) Tissue-infiltrating neutrophils constitute the major in vivo source of angiogenesis-inducing MMP-9 in the tumor microenvironment. Neoplasia 16, 771–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Deryugina EI and Quigley JP (2015) Tumor angiogenesis: MMP-mediated induction of intravasation- and metastasis-sustaining neovasculature. Matrix Biol. 44–46, 94–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thirkettle S et al. (2013) Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (collagenase 2) induces the expression of interleukins 6 and 8 in breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem 288, 16282–16294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mehner C et al. (2014) Tumor cell-produced matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) drives malignant progression and metastasis of basal-like triple negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 5, 2736–2749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wculek SK and Malanchi I (2015) Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature 528, 413–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Andzinski L et al. (2016) Type I IFNs induce anti-tumor polarization of tumor associated neutrophils in mice and human. Int. J. Cancer 138, 1982–1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fridlender ZG et al. (2009) Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: ‘N1’ versus ‘N2’ TAN. Cancer Cell 16, 183–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Casbon AJ et al. (2015) Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, E566–E575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coffelt SB et al. (2015) IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 522, 345–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Raccosta L et al. (2013) The oxysterol-CXCR2 axis plays a key role in the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils. J. Exp. Med 210, 1711–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jamieson T et al. (2012) Inhibition of CXCR2 profoundly suppresses inflammation-driven and spontaneous tumorigenesis. J. Clin. Invest 122, 3127–3144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Steele CW et al. (2016) CXCR2 inhibition profoundly suppresses metastases and augments immunotherapy in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 29, 832–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Granot Z et al. (2011) Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell 20, 300–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gershkovitz M et al. (2018) TRPM2 mediates neutrophil killing of disseminated tumor cells. Cancer Res. 78, 2680–2690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Matlung HL et al. (2018) Neutrophils kill antibody-opsonized cancer cells by trogoptosis. Cell Rep. 23, 3946–3959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Richter J et al. (1990) Tumor necrosis factor-induced degranulation in adherent human neutrophils is dependent on CD11b/CD18-integrin-triggered oscillations of cytosolic free Ca2+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 87, 9472–9476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Houghton AM et al. (2010) Neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation of IRS-1 accelerates lung tumor growth. Nat. Med 16, 219–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dallegri F et al. (1991) Tumor cell lysis by activated human neutrophils: analysis of neutrophil-delivered oxidative attack and role of leukocyte function-associated antigen 1. Inflammation 15, 15–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Finisguerra V et al. (2015) MET is required for the recruitment of anti-tumoural neutrophils. Nature 522, 349–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tecchio C et al. (2004) IFNalpha-stimulated neutrophils and monocytes release a soluble form of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL/Apo-2 ligand) displaying apoptotic activity on leukemic cells. Blood 103, 3837–3844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tecchio C et al. (2013) On the cytokines produced by human neutrophils in tumors. Semin. Cancer Biol. 23, 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sippel TR et al. (2015) Arginase I release from activated neutrophils induces peripheral immunosuppression in a murine model of stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35, 1657–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang F et al. (2017) The diverse biological functions of neutrophils, beyond the defense against infections. Inflammation 40, 311–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Donati K et al. (2017) Neutrophil-derived interleukin 16 in premetastatic lungs promotes breast tumor cell seeding. Cancer Growth Metastasis 10, 1179064417738513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Liang W et al. (2018) Metastatic growth instructed by neutrophil-derived transferrin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 115, 11060–11065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.McLoed AG et al. (2016) Neutrophil-derived IL-1beta impairs the efficacy of NF-kappaB inhibitors against lung cancer. Cell Rep. 16, 120–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Shultz LD et al. (2019) Humanized mouse models of immunological diseases and precision medicine. Mamm. Genome 30, 123–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hosur V et al. (2017) Development of humanized mice in the age of genome editing. J. Cell. Biochem 118, 3043–3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ito M et al. (2002) NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood 100, 3175–3182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Shultz LD et al. (2005) Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R gamma null mice engrafted with mobilized human hemopoietic stem cells. J. Immunol 174, 6477–6489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Song J et al. (2010) A mouse model for the human pathogen Salmonella typhi. Cell Host Microbe 8, 369–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Traggiai E et al. (2004) Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science 304, 104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Brehm MA et al. (2012) Engraftment of human HSCs in nonirradiated newborn NOD-scid IL2rgamma null mice is enhanced by transgenic expression of membrane-bound human SCF. Blood 119, 2778–2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Takagi S et al. (2012) Membrane-bound human SCF/KL promotes in vivo human hematopoietic engraftment and myeloid differentiation. Blood 119, 2768–2777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Coughlan AM et al. (2016) Myeloid engraftment in humanized mice: impact of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor treatment and transgenic mouse strain. Stem Cells Dev. 25, 530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wunderlich M et al. (2010) AML xenograft efficiency is significantly improved in NOD/SCID-IL2RG mice constitutively expressing human SCF, GM-CSF and IL-3. Leukemia 24, 1785–1788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jangalwe S et al. (2016) Improved B cell development in humanized NOD-scid IL2Rgamma(null) mice transgenically expressing human stem cell factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3. Immun. Inflamm. Dis 4, 427–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Verma MK et al. (2017) A novel hemolytic complement-sufficient NSG mouse model supports studies of complement-mediated antitumor activity in vivo. J. Immunol. Methods 446, 47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shultz LD et al. (2014) Human cancer growth and therapy in immunodeficient mouse models. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2014, 694–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yao LC et al. (2019) Creation of PDX-bearing humanized mice to study immuno-oncology. Methods Mol. Biol. 1953, 241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ngo M et al. (2016) Antibody therapy targeting CD47 and CD271 effectively suppresses Melanoma metastasis in patient-derived xenografts. Cell Rep. 16, 1701–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hagerling C et al. (2019) Immune effector monocyte-neutrophil cooperation induced by the primary tumor prevents metastatic progression of breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 21704–21714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.van Lent AU et al. (2009) IL-7 enhances thymic human T cell development in ‘human immune system’ Rag2−/−IL-2Rgammac−/− mice without affecting peripheral T cell homeostasis. J. Immunol 183, 7645–7655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Naso MF et al. (2017) Adeno-associated virus (AAV) as a vector for gene therapy. BioDrugs 31, 317–334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chen Q et al. (2009) Expression of human cytokines dramatically improves reconstitution of specific human-blood lineage cells in humanized mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A 106, 21783–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Huntington ND et al. (2011) IL-15 transpresentation promotes both human T-cell reconstitution and T-cell-dependent antibody responses in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 6217–6222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Billerbeck E et al. (2011) Development of human CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in human stem cell factor-, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-, and interleukin-3-expressing NOD-SCID IL2Rgamma(null) humanized mice. Blood 117, 3076–3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nicolini FE et al. (2004) NOD/SCID mice engineered to express human IL-3, GM-CSF and Steel factor constitutively mobilize engrafted human progenitors and compromise human stem cell regeneration. Leukemia 18, 341–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Goodwin LO et al. (2019) Large-scale discovery of mouse transgenic integration sites reveals frequent structural variation and insertional mutagenesis. Genome Res. 29, 494–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hasenberg A et al. (2015) Catchup: a mouse model for imaging-based tracking and modulation of neutrophil granulocytes. Nat. Methods 12, 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kawase E et al. (1994) Strain difference in establishment of mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell lines. Int. J. Dev. Biol 38, 385–390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Yao X et al. (2017) Homology-mediated end joining-based targeted integration using CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Res. 27, 801–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Miura H et al. (2018) Easi-CRISPR for creating knock-in and conditional knockout mouse models using long ssDNA donors. Nat. Protoc 13, 195–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ohtsuka M et al. (2018) i-GONAD: a robust method for in situ germline genome engineering using CRISPR nucleases. Genome Biol. 19, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Quadros RM et al. (2017) Easi-CRISPR: a robust method for one-step generation of mice carrying conditional and insertion alleles using long ssDNA donors and CRISPR ribonucleoproteins. Genome Biol. 18, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Miura H et al. C(2015) RISPR/Cas9-based generation of knockdown mice by intronic insertion of artificial microRNA using longer single-stranded DNA. Sci. Rep 5, 12799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Aida T et al. (2014) Translating human genetics into mouse: the impact of ultra-rapid in vivo genome editing. Dev. Growth Differ. 56, 34–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Singh P et al. (2015) A mouse geneticist’s practical guide to CRISPR applications. Genetics 199, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gurumurthy CB and Lloyd KCK. (2019) Generating mouse models for biomedical research: technological advances. Dis. Model. Mech 12, XXX–YYY [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Xu Z et al. (2013) Accuracy and efficiency define Bxb1 integrase as the best of fifteen candidate serine recombinases for the integration of DNA into the human genome. BMC Biotechnol. 13, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Smith MC et al. (2010) Site-specific recombination by phiC31 integrase and other large serine recombinases. Biochem. Soc. Trans 38, 388–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Brown WR et al. (2011) Serine recombinases as tools for genome engineering. Methods 53, 372–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tasic B et al. (2011) Site-specific integrase-mediated transgenesis in mice via pronuclear injection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 108, 7902–7907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Linder CC (2001) The influence of genetic background on spontaneous and genetically engineered mouse models of complex diseases. Lab. Anim 30, 34–39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Montagutelli X (2000) Effect of the genetic background on the phenotype of mouse mutations. J. Am .So. Nephrol 11 (Suppl. 16), S101–D105 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Saul MC et al. (2019) High-diversity mouse populations for complex traits. Trends Genet. 35, 501–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Churchill GA et al. (2004) The Collaborative Cross, a community resource for the genetic analysis of complex traits. Nat. Genet 36, 1133–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Threadgill DW et al. (2002) Genetic dissection of complex and quantitative traits: from fantasy to reality via a community effort. Mamm. Genome 13, 175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Peirce JL et al. (2004) A new set of BXD recombinant inbred lines from advanced intercross populations in mice. BMC Genet. 5, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ashbrook DG et al. (2019) The expanded BXD family of mice: a cohort for experimental systems genetics and precision medicine. bioRxiv 2019, 672097 [Google Scholar]

- 139.Svenson KL et al. (2012) High-resolution genetic mapping using the Mouse Diversity outbred population. Genetics 190, 437–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Wang X et al. (2016) Joint mouse-human phenome-wide association to test gene function and disease risk. Nat. Commun 7, 10464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bogue MA et al. (2019) Mouse Phenome Database: a data repository and analysis suite for curated primary mouse phenotype data. Nucleic Acids Res. ZZ, XXX–YYY [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Gatti DM et al. (2014) Quantitative trait locus mapping methods for diversity outbred mice. G3 4, 1623–1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kelada SN et al. (2012) Genetic analysis of hematological parameters in incipient lines of the collaborative cross. G3 2, 157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Collin R et al. (2019) Common heritable immunological variations revealed in genetically diverse inbred mouse strains of the Collaborative Cross. J. Immunol. 202, 777–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]