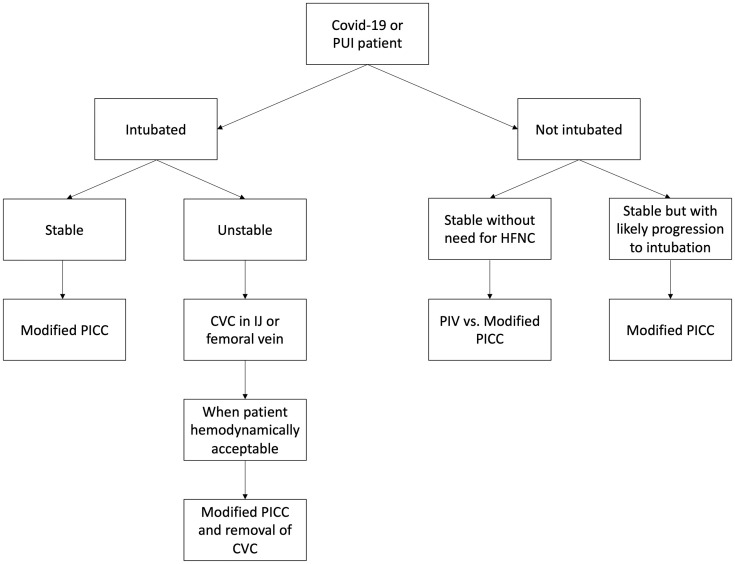

From our single tertiary-center experience, many patients who develop coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection require rapid escalation of care with mechanical ventilation, multiagent sedation and vasopressor support. Early on, more than 430 patients were hospitalized with approximately 25% requiring mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit care. These patients require central venous access catheters (CVC), hence increasing significantly the exposure time for both physicians and nurses. After discussion between intensive care unit physicians and the vascular surgery team, a decision was made to utilize triple-lumen peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) as the preferred means of establishing central vein access. A protocol for modified PICC insertion (Fig ) was designed to meet the high demand for access.

Fig.

Guidance protocol for PICC insertion depending on the patient's clinical condition. HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; IJ, internal jugular; PUI, person under investigation.

With ultrasound guidance, we identified a feasible upper arm superficial (cephalic or basilic) or deep (brachial) vein and inserted a PICC without the catheter-navigation and tip-confirmation technology. To avoid propagation of the catheter tip in the right atrium and subsequent need for catheter adjustment, we cut the length of the PICC at about the proximal one-third of the clavicle. This way, the procedure takes 15-20 minutes total time in the patient's room, the catheter tip is within the ipsilateral subclavian or brachiocephalic vein and a confirmation chest radiograph is not required before use.

During the first stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, a dedicated PICC-team performed 112 PICC insertions in 112 patients with COVID-19. The technical success was 100% and the basilic vein was most commonly used. Follow-up after PICC insertion ranges from 10 to 21 days. None of the patients developed catheter-related infections or upper extremity deep venous thrombosis related to PICC placement. One patient developed limited-extend cephalic vein superficial thrombophlebitis while on therapeutic anticoagulation, so continuous use of the PICC was recommended. No line malfunction was reported, and no requests were received to replace PICC. Of note, an institutional anticoagulation protocol based on d-dimer levels was being followed for all coronavirus patients at the time.

Many patients with severe COVID-19 require pressor support early in the hospital course to maintain hemodynamic stability.1 These patients require mechanical ventilation for a prolonged period.2 The use of PICC as preferred CVC offers a number of advantages: (a) the time required for insertion, hence staff exposure is low; (b) PICCs can stay in place longer than CVCs, thus decreasing the need for line replacement; (c) the rate of complications requiring operative intervention with PICCs is lower than that seen with CVCs3; (d) although the infection rate of CVCs and PICCs appears to be similar in the literature, the median time to development of bloodstream infection with PICC is significantly longer4; and (e) given the high rates of acute renal failure, central access (internal jugular and femoral veins) remains available for placement of dialysis catheters.

These short-term observations support the strategy of using PICCs as low risk, effective, and reliable option for central venous access in patients with COVID-19. We intend to continue monitoring our patients and report their longer term outcomes.

References

- 1.Arentz M., Yim E., Klaff L., Lokhandwala S., Riedo F.X., Chong M., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K., et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the seattle region - case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornbau C., Lee K., Hughes G., Firstenberg M. Central line complications. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2015;5:170. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.164940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Raiy B., Fakih M.G., Bryan-Nomides N., Hopfner D., Riegel E., Nenninger T., et al. Peripherally inserted central venous catheters in the acute care setting: a safe alternative to high-risk short-term central venous catheters. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]