Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus that causes the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which the World Health Organization classified as a pandemic in March 2020. New York is now the epicenter of the outbreak in the United States. Recent publications have advocated for universal testing for COVID-19 infection in pregnant women admitted to labor and delivery units owing to the presence of asymptomatic carriers of the virus.1 In fact, most patients who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 may be asymptomatic.2 , 3 Our health system recently implemented a universal testing protocol to reduce the risk of occult transmission of SARS-CoV-2. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of peripartum COVID-19 infection and the rate of asymptomatic carriers in pregnant women admitted for delivery during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in New York. We also sought to determine if there are differences between the sites that reflect the demographic variations in the local populations served by each hospital.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective cohort study evaluated all women admitted for delivery at 4 hospitals within Northwell Health, the largest academic health system in New York, between April 2 and April 9, 2020. Respiratory specimens were obtained by nasopharyngeal swabs either within 1 hour of hospital admission or within 48 hours before admission for a scheduled induction of labor or cesarean delivery. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) tests were performed on the nasopharyngeal swab specimens for the detection of SARS-CoV-2. Antepartum admissions, triage evaluations, and hospitalizations that began before the implementation of the universal testing protocol were excluded. The Northwell Health Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Clinical and laboratory data were obtained from the electronic medical record systems. All charts, regardless of the SARS-CoV-2 results, were manually reviewed for signs and symptoms of COVID-19 infection; specifically, the admission history and physical examination document signed by the attending physician and any triage documentation preceding it were evaluated for the presence or absence of fever, cough, dyspnea, myalgia, and fatigue. The primary variables of interest were the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results and the presence or absence of signs and symptoms indicative of a COVID-19 infection. Each hospital site was evaluated separately and the results were compared with those of the other hospitals. Comparisons of the continuous variables between the groups were performed by using either the Mann-Whitney test or the t-test, as appropriate. The Fisher exact test or the chi-square test was used, as appropriate, to examine the associations among categorical variables. Statistical significance was defined as P<.05.

Results

A total of 403 women were admitted to the obstetrical unit at the 4 hospital sites. After exclusion of 16 antepartum admissions and 5 postpartum readmissions, there were 382 women admitted for delivery, of whom 375 had molecular diagnostic testing per the universal testing protocol and 64 (17.1%) of them tested positive for SARS-CoV-2; 7 women were previously tested and diagnosed with COVID-19 secondary to symptoms. Thus, the overall prevalence of positive SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing was 18.6% (71 of 382).

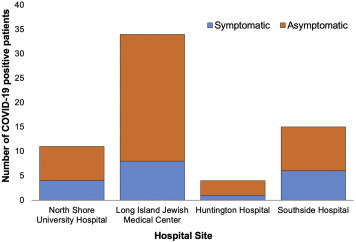

Among the 64 women who were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in universal testing, 70.3% were asymptomatic; this did not differ significantly across the 4 hospitals (Figure ). Three patients who tested negative reported symptoms, and, in each case, an alternative diagnosis was strongly suspected (eg, fever associated with intraamniotic infection). Among the symptomatic patients diagnosed with COVID-19 at the time of universal testing (19 of 64), a cough was the most common symptom (57.9%), followed by fever (52.6%) and dyspnea (47.4%).

Figure.

Symptomatic and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection identified on universal testing

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Blitz. Universal COVID-19 testing at delivery. AJOG MFM 2020.

Considerable heterogeneity was observed across the sites (Table ). At the hospital with the highest prevalence of viral infection (28.8%), 57.7% of the population was Hispanic, compared with 9.4% at the site with the lowest prevalence (10.9%). Overall, among the patients who identified as Hispanic, 31.9% tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 compared with 21.3% of non-Hispanic black people and 14.1% of non-Hispanic white people (P<.008).

Table.

Maternal demographics and clinical characteristics

| Variables | Overall (n=382) | North Shore University Hospital (n=128) | Long Island Jewish Medical Center (n=167) | Huntington Hospital (n=35) | Southside Hospital (n=52) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y | 32.9±5.3 | 34.0±5.0 | 32.2±5.1 | 34.2±5.1 | 31.6±6.2 | <.004 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 156 (42.2) | 71 (55.5) | 58 (34.9) | 13 (54.2) | 14 (26.9) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 61 (16.5) | 12 (9.4) | 43 (25.9) | 2 (8.3) | 4 (7.7) | |

| Asian | 56 (15.1) | 24 (18.8) | 30 (18.1) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 72 (19.5) | 12 (9.4) | 22 (13.3) | 8 (33.3) | 30 (57.7) | |

| Other | 25 (6.8) | 9 (7.0) | 13 (7.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (5.8) | |

| Gestational age, wk | 39.2 (38.3–40.0) | 39.2 (38.4–39.5) | 39.2 (38.3–40.0) | 39.3 (38.5–40.0) | 39.2 (38.1–40.1) | .74 |

| COVID-19 testing | ||||||

| Previous PCR positiveb | 7 (1.8) | 3 (2.3) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | .78 |

| Universal testing | 375 (98.2) | 125 (97.7) | 164 (98.2) | 34 (97.1) | 52 (100.0) | |

| PCR positive | 64 (17.1) | 11 (8.8) | 34 (20.7) | 4 (11.8) | 15 (28.8) | <.004 |

| PCR negative | 311 (82.9) | 114 (91.2) | 130 (79.3) | 30 (88.2) | 37 (71.2) |

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation, n (percentage), or median (interquartile range).

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Blitz. Universal COVID-19 testing at delivery. AJOG MFM 2020.

Race/ethnicity data were available for 96.9% of patients (n=370)

COVID-19 PCR testing was conducted more than 48 h before admission, secondary to symptoms.

Discussion

At the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak in New York, approximately 1 in 5 women presenting for delivery tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Asymptomatic carriers were common, comprising more than two-thirds of women with a laboratory-confirmed viral infection. It is certainly possible that these women were presymptomatic because the median incubation period for COVID-19 is approximately 5 days. Demographic factors such as race and ethnicity are strongly associated with disease prevalence; Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women were disproportionately more affected.

Other institutions in New York recently described their early experience with the universal testing for SARS-CoV-2 in labor and delivery units, and, like our study, observed a high proportion of asymptomatic patients.2 , 3 The reason for such high variability in the clinical presentation or outcomes is still unkown.4 It is possible that more virulent strains of the virus exist or that exposure to higher viral loads affect the rate of transmission. However, early reports suggest that viral loads in asymptomatic patients are similar to those in symptomatic ones.5

No previous investigation has evaluated the prevalence of peripartum COVID-19 infection, the rate of asymptomatic carriers, or the association between race and ethnicity and viral infection across several sites in the same region during the same period. Our study, however, has some limitations. Structured documentation of COVID-19 symptoms was lacking. Patients who reported no complaints may have had positive responses with more systematic questioning. Moreover, patients may have been hesitant to endorse symptoms, for fear of the potential implications for a support person and/or infant separation; thus, symptom prevalence may be underestimated due to information bias. However, misclassification bias during data retrieval was reduced by employing a systematic, universal chart review regardless of the RT-PCR results. Finally, we did not follow patients longitudinally and it is not known if, or when, asymptomatic patients developed symptoms.

Universal testing for SARS-CoV-2 in pregnant women admitted for delivery identifies many patients with viral infection who would have been missed via symptom-based screening. A heightened awareness of the potential for asymptomatic viral infection in areas with high community transmission will allow health systems to optimize their approaches to keep patients, their families, and healthcare providers safe. Precautions such as the use of full body personal protective equipment, including N95 respirators, will remain necessary for all the staff in labor and delivery units during prolonged contact, the second stage of labor, and delivery, to prevent the exposure and spread of this virus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Fernando Suarez for the assistance with clinical data retrieval.

Footnotes

This paper is part of a supplement that represents a collection of COVID-related articles selected for publication by the editors of AJOG MFM without additional financial support.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

This study was conducted in Manhasset, NY.

References

- 1.Breslin N., Baptiste C., Gyamfi-Bannerman C., et al. COVID-19 infection among asymptomatic and symptomatic pregnant women: two weeks of confirmed presentations to an affiliated pair of New York City hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100118. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sutton D., Fuchs K., D’Alton M., Goffman D. Universal screening for SARS-CoV-2 in women admitted for delivery. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2163–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vintzileos W.S., Muscat J., Hoffmann E., et al. Screening all pregnant women admitted to Labor and Delivery for the virus responsible for COVID-19. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.024. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dashraath P., Wong J.L.J., Lim M.X.K., et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]