Abstract

Introduction

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is often diagnostically challenging. Only limited data exist on the performance of interferon-γ release assays (IGRA) and molecular assays in children with TBM in routine clinical practice, particularly in the European setting.

Methods

Multicentre, retrospective study involving 27 healthcare institutions providing care for children with tuberculosis (TB) in nine European countries.

Results

Of 118 children included, 54 (45.8%) had definite, 38 (32.2%) probable and 26 (22.0%) possible TBM; 39 (33.1%) had TBM grade 1, 68 (57.6%) grade 2 and 11 (9.3%) grade 3. Of 108 patients who underwent cranial imaging 90 (83.3%) had at least one abnormal finding consistent with TBM. At the 5-mm cut-off the tuberculin skin test had a sensitivity of 61.9% (95% CI 51.2–71.6%) and at the 10-mm cut-off 50.0% (95% CI 40.0–60.0%). The test sensitivities of QuantiFERON-TB and T-SPOT.TB assays were 71.7% (95% CI 58.4–82.1%) and 82.5% (95% CI 58.2–94.6%), respectively (p=0.53). Indeterminate results were common, occurring in 17.0% of QuantiFERON-TB assays performed. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures were positive in 50.0% (95% CI 40.1–59.9%) of cases, and CSF PCR in 34.8% (95% CI 22.9–43.7%). In the subgroup of children who underwent tuberculin skin test, IGRA, CSF culture and CSF PCR simultaneously, 84.4% had at least one positive test result (95% CI 67.8%–93.6%).

Conclusions

Existing immunological and microbiological TB tests have suboptimal sensitivity in children with TBM, with each test producing false-negative results in a substantial proportion of patients. Combining immune-based tests with CSF culture and CSF PCR results in considerably higher positive diagnostic yields, and should therefore be standard clinical practice in high-resource settings.

Short abstract

All existing immunological and microbiological TB tests have suboptimal sensitivity in children with TBM. Combining immune-based tests with CSF culture and PCR results in far higher positive diagnostic yields, and should therefore be standard practice. http://bit.ly/2TSAArl

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 1 million children and adolescents develop active tuberculosis (TB) annually, with the majority of the disease burden occurring in low-resource countries [1]. In most European countries the incidence of TB disease has been declining steadily over recent decades, but drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis has brought new challenges, particularly in Eastern Europe [2].

TB meningitis (TBM) is an uncommon manifestation of TB disease, but is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, even in high-resource settings [3]. Children with TBM frequently present with nonspecific symptoms and without a history of TB contact, and diagnosing TBM is therefore often challenging [4–6]. Importantly, previous data suggest that delays in diagnosis are linked to poor outcomes [7].

TB diagnostics used in routine clinical practice have evolved significantly over the past two decades, with the introduction of interferon-γ release assays (IGRAs) and a variety of commercial molecular assays [8]. Recent data show that both IGRAs and molecular TB assays are widely available across Europe, and are used extensively by paediatric TB specialists [9, 10].

Immune-based TB tests, comprising tuberculin skin tests (TSTs) and IGRAs, are commonly used as adjunctive diagnostic tools in children with suspected TB disease [8], but the existing data on the performance of IGRAs specifically in children with TBM remain very limited [11, 12]. In addition, although a small number of studies have investigated the use of molecular TB assays in children with suspected TBM, most of these were small, limited to a single study site, or from low-resource settings where late presentations are likely to be more common than in Europe [4, 13, 14]. Furthermore, most studies were conducted under protocolised study conditions, and therefore prone to overestimating test sensitivity compared to performance in routine clinical settings.

This study aimed to determine the sensitivity of immunological, conventional microbiological and molecular TB tests in children with TBM in the context of routine clinical care in Europe. Secondary aims were to describe clinical features and radiological findings at presentation, and to evaluate the Uniform TBM Research Case Definition (UTRCD) score in the European setting.

Methods

European members of the Paediatric Tuberculosis Network European Trials Group (ptbnet), which at that point in time included 214 clinicians and researchers based in 31 European countries [9, 10, 15, 16], were invited to retrospectively report children and adolescents (aged 0–16 years) with TBM who had received healthcare at their institution. The study opened in February 2016 and reporting closed in August 2016. Data were collected via a web-based tool creating a standardised dataset for each case. The study was reviewed and approved by the human ethics committee of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the ptbnet steering committee. No personal or identifiable data were collected during the conduct of this study.

Classification of cases

Cases were categorised as definite TBM, probable TBM or possible TBM, according to consensus definitions based on the UTRCD score (supplementary table S1) [3], with minor modifications, as follows. The item “history of close contact with an individual with pulmonary TB or a positive TST or IGRA”, scoring 2 points in the original criteria was split into two separate items: 1) history of close contact with an individual with pulmonary TB and 2) a positive TST (≥10 mm) and/or IGRA, each scoring one point if present. Furthermore, “choroidal tubercles” was added to the category “evidence of tuberculosis elsewhere”, scoring 1 point if present; the maximum category score of 4 was retained. If no data were available for one particular item, the respective item was scored as 0. Briefly, definite TBM was defined as a patient with clinical entry criteria (headache, irritability, vomiting, fever, neck stiffness, convulsions, focal neurological deficits, altered consciousness or lethargy) plus one or more of the following: acid-fast bacilli detected in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), M. tuberculosis cultured from CSF or M. tuberculosis detected by PCR in CSF. Probable TBM was defined as presence of clinical entry criteria plus a total diagnostic score of ≥12, and possible TBM as presence of clinical entry criteria plus a total diagnostic score of 6–11.

Disease severity

Disease severity was graded according to the modified British Medical Research Council (BMRC) criteria [17, 18]. In brief, grade 1 corresponds to a Glasgow coma score of 15 with no neurological signs, grade 2 a score of 11–14 or a score of 15 with focal neurological signs, and grade 3 a score of ≤10.

Statistical analysis

Nonparametric two-tailed Mann–Whitney U-tests were used to compare continuous variables. The sensitivities of diagnostic tests were compared using two-tailed Fisher's exact tests. In cases where a TST was performed and reported as negative, but with no result of induration in millimetres available, it was considered as missing data at the 5-mm threshold and as a negative result at the 10-mm threshold; if a TST was reported as positive without induration size, it was considered as positive at the 10-mm threshold, and hence also positive at the 5-mm threshold. The 95% confidence intervals around proportions were calculated using the Wald method. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out for associations between positive IGRA, positive TST (at the 5-mm and 10-mm thresholds) and indeterminate IGRA as outcome variables, with predictor variables of age, sex, bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination status, TBM staging and definite TBM diagnosis. Models were evaluated using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test and receiver operating characteristic curves showed an area under the curve ≥0.7. The primary outcome measures were odds ratios. The 95% confidence interval was calculated for each odds ratio, and p-values <0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were done using Prism (version 8.0; GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) and Stata (version 12.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The study is reported in accordance with Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies guidelines.

Results

27 healthcare institutions, situated in Bulgaria (n=1), Finland (n=1), Germany (n=3), Greece (n=1), Italy (n=3), Slovenia (n=1), Spain (n=12), Sweden (n=2) and the United Kingdom (n=3), contributed cases to the study.

118 children were included in the final analysis, comprising 54 (45.8%) definite, 38 (32.2%) probable and 26 (22.0%) possible TBM cases. With regards to disease severity, 39 (33.1%) were BMRC TBM grade 1, 68 (57.6%) grade 2 and 11 (9.3%) grade 3.

The demographic details are shown in table 1. The median (interquartile range (IQR)) age was 2.7 (1.1–6.4) years. Although the majority (89.8%) of children had been born in Europe, almost half of these (48.3%) were from families with one or both parent(s) originating from a country with high TB prevalence. Almost half (41.5%) had a history of TB contact. A test for HIV was performed in 73 (61.9%) children; only two (2.7%) were positive.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographic data and clinical features at presentation

| Age years | 2.7 (1.1–6.4) |

| Male:female | 1.1:1.0 |

| Born in Europe | 106 (89.8) |

| Born in Europe with one or both parent(s) originating from a high TB incidence country | 57 (48.3) |

| Born outside Europe | 12 (10.2) |

| Africa | 6 (50.0) |

| Asia | 3 (25.0) |

| South America | 3 (25.0) |

| Prior BCG vaccination | |

| Yes | 22 (18.6) |

| No | 80 (67.8) |

| Unknown | 16 (13.6) |

| Known TB contact | |

| Yes | 49 (41.5) |

| No | 67 (56.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.7) |

| Constitutional symptoms at presentation | |

| Fever | 99 (83.9) |

| Weight loss | 32 (27.1) |

| Night sweats | 10 (8.5) |

| Neurological symptoms at presentation | |

| Vomiting | 70 (59.3) |

| Altered consciousness | 55 (46.6) |

| Headache | 52 (44.1) |

| Lethargy | 27 (22.9) |

| Cranial nerve palsy | 26 (22.0) |

| Seizures | 25 (21.2) |

| Ataxia | 5 (4.2) |

| Paresis | 3 (2.5) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range), n or n (%). TB: tuberculosis; BCG: bacille Calmette–Guérin.

The commonest constitutional symptom at presentation was fever. The most common neurological symptoms at presentation comprised vomiting, headache and altered level of consciousness (table 1).

Distribution of the UTRCD score among subgroups

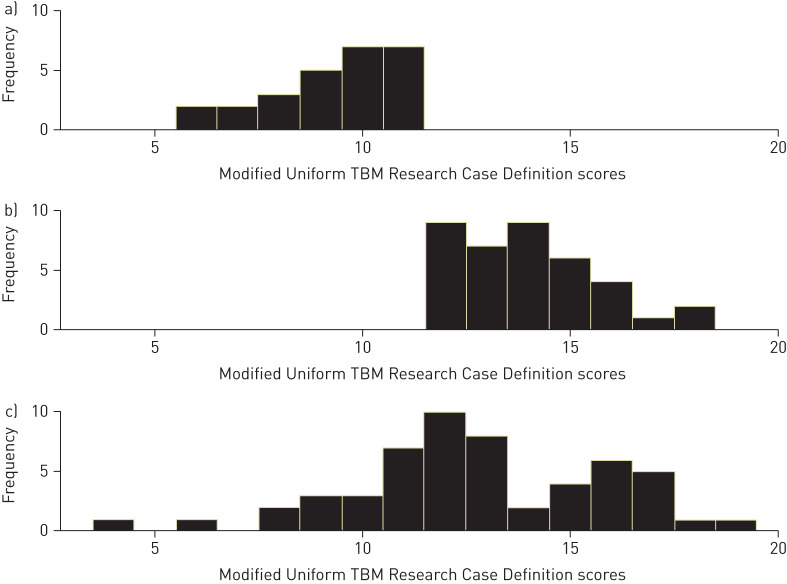

In the group of patients with definite TBM the mean±sd score was 12.8±3.1 (range 4–19). In the patients with probable or possible TBM combined, the mean score was 12.1±2.8 (6–18). Of the children with definite TBM, almost one-third (n=17, 31.5%) had scores <12 (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of modified Uniform Tuberculous Meningitis Research (TBM) Case Definition scores among cases with a) possible, b) probable and c) definite tuberculous meningitis.

Radiological investigations

Of 112 patients who underwent chest radiography, 81 (72.3%) had changes suggestive of intrathoracic TB disease, including hilar lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, consolidation or cavitation (table 2). In 26 (22.8%) cases miliary infiltrates were identified.

TABLE 2.

Radiological findings on chest radiography, abdominal ultrasound scan and cranial imaging with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

| Chest radiography | 112 |

| Changes suggestive of active TB# | 81 (72.3) |

| Changes suggestive of previous pulmonary TB¶ | 2 (1.8) |

| No abnormalities detected | 29 (25.9) |

| Abdominal ultrasound scan | 65 |

| Hepatomegaly | 10 (15.4) |

| Splenomegaly | 9 (13.8) |

| Intra-abdominal granulomas | 11 (16.9) |

| Miliary lesions | 4 (6.2) |

| Enlarged lymph nodes | 2 (3.1) |

| No abnormalities detected | 42 (64.6) |

| Cranial CT/MRI | 108 |

| Hydrocephalus | 53 (49.1) |

| Basal meningeal enhancement | 44 (40.7) |

| Intracranial tuberculomas | 32 (29.6) |

| Cerebral infarcts | 14 (13.0) |

| No abnormalities detected | 18 (16.7) |

Data are presented as n or n (%). TB: tuberculosis. #: hilar adenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, consolidation or cavitation; ¶: fibrotic scars or calcification.

65 patients had an abdominal ultrasound scan. In the majority (64.6%), no abnormalities were detected. The most common abnormal findings were hepatomegaly, splenomegaly and intrabdominal granulomas (table 2).

In 108 patients, cranial imaging with computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging was performed. Of those, 90 (83.3%) had one or more abnormal findings consistent with TBM. The most common finding was hydrocephalus, followed by basal meningeal enhancement and intracranial tuberculomas (table 2). In the remaining 18 (16.7%) patients, no significant abnormalities were identified, which included six children with definite TBM.

Performance of immunological TB tests

TST, QuantiFERON Gold assay and T-SPOT.TB assay (both performed on blood samples) results were available in 92, 53 and 17 patients, respectively. In 10 patients neither TST nor IGRA results were available.

Table 3 summarises the results of 108 patients in whom TST and/or IGRA results were available. Of the 54 children in whom both TST and IGRA results were available only six (11.1%) had concordantly negative TST (at the 10-mm threshold) and IGRA results; five (9.3%) had negative TST and indeterminate QFT results; in the remaining 43 (79.6%), at least one immunological test result was positive.

TABLE 3.

Summary of tuberculin skin test (TST) and interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) results in patients who had at least one immunological test performed

| Patients | QFT positive | QFT negative | QFT indeterminate | T-SPOT positive | T-SPOT negative | T-SPOT indeterminate | No IGRA# | |

| TST cut-off 5 mm¶ | 84 | |||||||

| Positive | 18 (21.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | 8 (9.5) | 0 | 0 | 24 (28.5) | |

| Negative | 9 (10.7) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.8) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 12 (14.3) | |

| TST cut-off 10 mm | 92 | |||||||

| Positive | 16 (17.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | 6 (6.5) | 0 | 0 | 22 (23.9) | |

| Negative | 13 (14.1) | 4 (4.3) | 5 (5.4) | 6 (6.5) | 2 (2.2) | 0 | 16 (17.4) | |

| No TST+ | 16 | 9 (56.3) | 1 (6.3) | 3 (18.8) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0 |

Data are presented as n or n (%). n=108. QFT: QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay; T-SPOT: T-SPOT.TB assay. #: IGRA not performed or result not available; ¶: excludes eight patients who were negative at the 10-mm cut-off, but had no quantitative result recorded; +: TST not performed or result not available.

At the 5-mm cut-off the TST had a sensitivity of 61.9% (95% CI 51.2–71.6%), and at the 10-mm cut-off 50.0% (95% CI 40.0–60.0%). The sensitivities of the QFT and the T-SPOT.TB assay were 71.7% (95% CI 58.4–82.1%) and 82.5% (95% CI 58.2–94.6%), respectively. Statistically, there was no significant difference between the sensitivity of the TST at the 5-mm cut-off and the QFT assay (0.27); however, there was a significant difference at the 10-mm cut-off (p=0.0143). Similarly, no significant difference was detected between the TST at 5 mm and the T-SPOT.TB assay (p=0.16), but there was a significant difference at the 10 mm cut-off (p=0.0167). There was no statistically significant difference between the sensitivity of both IGRA assays (p=0.53). The proportion of positive TST results (at the 10-mm cut-off) did not differ significantly between BCG-vaccinated and BCG nonvaccinated children (47.1% versus 52.5%; p=0.78); in addition, there was no significant difference between those two subgroups with regards to TST induration size (median 8 mm versus 10 mm; p=0.81).

Of the 53 patients with QFT results, nine (17.0%) had an indeterminate test result (95% CI 9.0–29.5%). In the 17 patients with T-SPOT.TB results, there were no indeterminate results. There was no statistical difference between both IGRAs with regards to the proportion of indeterminate versus determinate (i.e. positive or negative) results (p=0.10). On average children with indeterminate test results were younger (median (IQR) age 2.0 (1.4–3.0) years) than children with determinate results (2.7 (1.0–6.5) years), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.22) (supplementary table S2).

CSF results

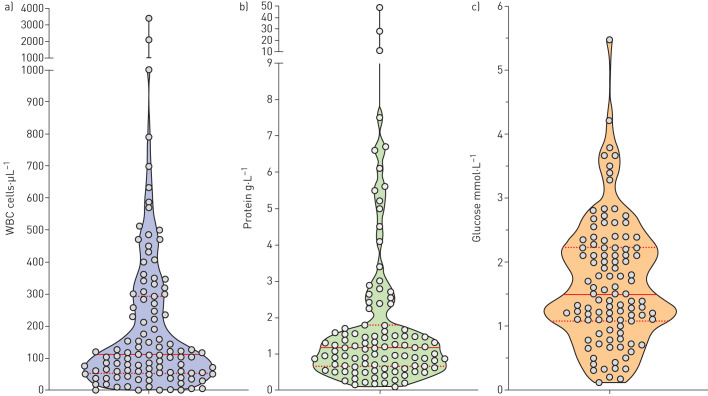

The CSF results at initial presentation in the 106 patients in whom those data were available are summarised in figure 2 and supplementary table S3. Only 10 (9.4%) patients had CSF protein concentrations within the normal range (0–0.4 g·L−1); in 57 (53.8%) patients, the CSF protein concentration was ≥1.0 g·L−1.

FIGURE 2.

Violin plots of cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell counts (WBC), protein and glucose concentrations at initial presentation. Horizontal lines indicate the medians and interquartile ranges.

Performance of microbiological tests with CSF

Results of acid-fast stains, mycobacterial culture and M. tuberculosis PCR testing on CSF were available in 75, 94 and 69 patients, respectively. Only three (4.0%) cases were positive for acid-fast bacilli (sensitivity 95% CI 0.9–11.6). 47 (50.0%) cases had positive mycobacterial culture results (95% CI 40.1–59.9%), while only 24 (34.8%) were positive on PCR testing (95% CI 22.9–43.7%), although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). Of the 62 cases in whom both mycobacterial culture and PCR had been performed on CSF, 17 were positive in both tests, 15 were positive only in culture, and four positive only in PCR. In this subgroup, performing both tests in parallel achieved greater sensitivity (36 (58.1%) out of 62, 95% CI 45.7–69.5%) than performing either culture (32 (51.6%) out of 62, 95% CI 39.5–63.6%) or PCR alone (21 (33.9%) out of 62, 95% CI 23.3–46.3%), but only the comparison with PCR alone was statistically significant (p=0.59 and p=0.0113, respectively).

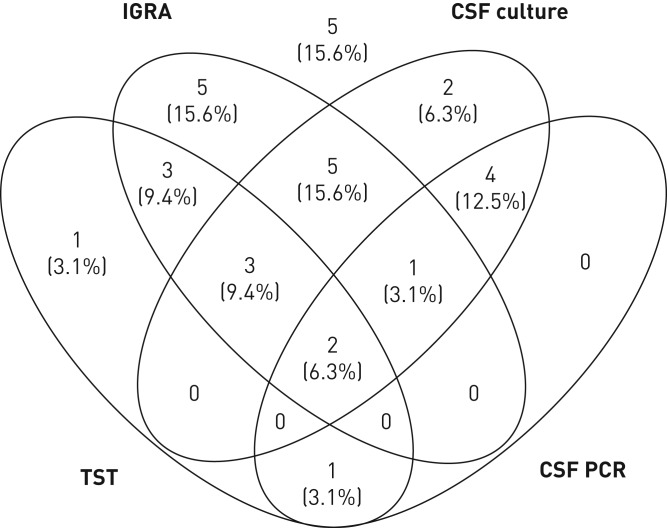

Combining immunological and microbiological tests

Figure 3 summarises the results of the subgroup of patients in whom both immunological and both mycobacterial culture and PCR on CSF had been performed (n=32), showing that TST-positive/IGRA-positive/CSF culture-positive and IGRA-positive only were the most common result constellations, but also that result constellations were very heterogeneous. Only five (15.6%) cases had negative results in all four tests; therefore, the overall sensitivity of all four tests combined was 84.4% (95% CI 67.8%–93.6%). Only one of those five cases had sampling performed at another site, a lymph node biopsy that was culture- and PCR-positive for M. tuberculosis.

FIGURE 3.

Venn diagram summarising positive tuberculin skin test (TST), interferon-γ release assay (IGRA) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) test results (culture and PCR) in the subgroup of patients who had all four tests performed (n=32). In five of those patients (shown above the diagram), all four tests were negative.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses

The results of the multivariate regression analyses for having a positive immunological test result are summarised in table 4. Children with TBM grade 3 were significantly less likely to have a positive TST (at both the 5-mm (OR 0.08, p=0.019) and the 10-mm cut-off (OR 0.06, p=0.023)) than those with TBM grade 1. However, this was not a statistically significant predictor of a positive IGRA result (OR 0.13, p=0.13). Younger children were more likely to have a positive IGRA result (OR 0.7 per year of increasing age, p=0.042). There were no statistically significant predictor variables of an indeterminate IGRA result in multivariate analysis (supplementary table S2).

TABLE 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for association between positive tuberculin skin test (TST) at the 5-mm and the 10-mm threshold, and positive interferon-γ release assay result (IGRA+) as outcome variable, and predictor variables of age, sex, bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination status, tuberculosis meningitis (TBM) staging, definite TBM diagnosis and IGRA type (for IGRA result only)

| Descriptor | Outcome variable (positive result) | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age years | Continuous | TST 5 mm | 0.89 (0.78–1.02) | 0.100 |

| TST 10 mm | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.103 | ||

| IGRA+ | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | 0.042 | ||

| Male | Binary | TST 5 mm | 0.43 (0.14–1.29) | 0.133 |

| TST 10 mm | 0.61 (0.22–1.66) | 0.331 | ||

| IGRA+ | 0.66 (0.16–2.69) | 0.560 | ||

| BCG status | Binary | TST 5 mm | 1.60 (0.33–7.71) | 0.560 |

| TST 10 mm | 1.27 (0.29–5.50) | 0.751 | ||

| IGRA+ | 1.52 (0.13–18.08) | 0.740 | ||

| TBM staging | Categorical | |||

| Stage 2 compared to stage 1 | TST 5 mm | 0.36 (0.11–1.21) | 0.100 | |

| TST 10 mm | 0.43 (0.15–1.25) | 0.121 | ||

| IGRA+ | 0.25 (0.03–1.85) | 0.180 | ||

| Stage 3 compared to stage 1 | TST 5 mm | 0.08 (0.01–0.65) | 0.019 | |

| TST 10 mm | 0.06 (0.00–0.68) | 0.023 | ||

| IGRA+ | 0.13 (0.01, 1.82) | 0.129 | ||

| Definite TBM diagnosis | Binary | TST 5 mm | 0.71 (0.24–2.10) | 0.540 |

| TST 10 mm | 0.37 (0.13–1.03) | 0.056 | ||

| IGRA+ | 0.82 (0.19–3.64) | 0.798 | ||

| Type of IGRA assay | Binary | |||

| T-SPOT.TB compared to QFT | IGRA+ | 22.15 (0.79–623.49) | 0.069 |

Indeterminate IGRA results were classified as negative for this analysis. Bold type represents p<0.05. T-SPOT: T-SPOT.TB assay; QFT: QuantiFERON-TB Gold assay.

Detection of M. tuberculosis at other sites

In 56 (47.5%) patients M. tuberculosis was detected in at least one clinical sample other than CSF (table 5). Of those, 49 (87.5%) were culture-positive and 27 (48.2%) were PCR-positive; 20 (35.7%) were positive in both culture and PCR. Among the 64 cases with possible and probable TBM (i.e. in whom M. tuberculosis was not identified in the CSF), M. tuberculosis was identified by culture and/or PCR at another site in 30 (46.9%) cases, securing a microbiological diagnosis in those patients.

TABLE 5.

Summary of microbiological test results of samples other than cerebrospinal fluid

| Patients | Positive for AFB | Positive in culture | Positive in PCR | |

| Sputum | 8 | 1 (12.5) | 6 (75.0) | 0 |

| Gastric aspirates | 42 | 10 (23.8) | 37 (88.1) | 18 (42.9) |

| Nasopharyngeal aspirate | 5 | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80) | 3 (60.0) |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | 7 | 3 (42.9) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (42.9) |

| Lymph node material | 4 | 0 | 3 (75.0) | 3 (75.0) |

Data are presented as n or n (%). AFB: acid-fast bacilli.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest multicentre study on TBM in children from a low TB incidence setting to date, facilitated by inclusion of a large number of participating centres across Europe via a well-established collaborative paediatric TB research network.

That this study was conducted in a low TB incidence setting is relevant for the interpretation of its findings. Almost a third (33.1%) of the cases had BMRC TBM grade 1 disease, while only 9.3% had grade 3 disease, contrasting with reports from high TB incidence countries, where the vast majority of patients have grade 2 or grade 3 disease at presentation [13]. This indicates that in the European setting there is a tendency for patients with TBM to present earlier and with less severe disease.

In addition, our cohort differs from most cohorts of children with TBM reported from high TB prevalence countries with regards to the proportion of cases that are microbiologically confirmed. Almost half (45.8%) of the cases in our cohort were confirmed, contrasting with studies from high prevalence settings in which fewer than a quarter were confirmed cases [14, 19, 20]. This may be the result of recall bias and preferential reporting of confirmed cases in our study, or alternatively may reflect the greater availability of diagnostic tests at the centres that participated in this study compared to lower resource settings. The latter hypothesis is supported by the fact that paediatric studies in high TB prevalence settings with access to molecular diagnostics have reported similar proportions of microbiologically confirmed cases [4, 21].

The performance of the UTRCD scoring system, which is based on expert consensus [3], was suboptimal in our cohort. Almost one-third (31.5%) of cases with microbiologically confirmed TBM had scores <12, which in the absence of a positive microbiological result would categorise those patients as “possible TBM”. It is possible that the comparatively poor performance relates to the tendency for European patients to present earlier (and therefore with fewer features and consequently lower scores) than patients in high TB prevalence settings. However, in some patients, certain data required for scoring (e.g. symptom duration) were not recorded, potentially resulting in the UTRCD scores of those patients being skewed towards lower values. However, importantly, this scoring system was developed for research purposes, and not for clinical decision-making.

Radiological changes suggestive of intrathoracic TB disease were present in almost three-quarters (72.3%) of the cases. This highlights that patients with suspected TBM should routinely undergo chest imaging, as this is likely to provide useful information aiding diagnosis. However, our data contrast with data from other studies that reported chest radiography changes in considerably lower proportions of children with TBM, typically 40–60% [19, 22, 23]. The observation that a high proportion (83.3%) of children in our cohort had abnormal findings on cranial imaging, including hydrocephalus, basal meningeal enhancement and intracranial tuberculomas, is consistent with previous reports [19, 20, 22].

Our data highlight that all existing immunological and microbiological TB tests have suboptimal sensitivity in children with TBM. TST, QFT assays and T-SPOT.TB assays had sensitivities of ∼80% or below, indicating that approximately one in five children with TBM have a false-negative result when a single immunological test is performed, irrespective of which test is used. Several recent studies, including in patients with TBM, have investigated novel immune-based TB biomarkers in blood that have the potential to improve the diagnosis of TB in children, but additional studies will be required to confirm their findings [24–26]. Interestingly, our multivariate logistic regression analyses indicate that false-negative TST results were more common in children with more severe TBM. Furthermore, we found that a large proportion of patients had discordant TST and IGRA results, in accordance with observations reported by studies in children with pulmonary TB [24, 27, 28].

It was striking that a substantial proportion of children had indeterminate IGRA test results. Among children who had undergone testing with QFT assays, 17.0% had an indeterminate result, which is considerably higher than in most studies that investigated the performance of QFT assays in children with pulmonary TB [24, 27, 29, 30]. Interestingly, the association between tuberculous central nervous system (CNS) disease and indeterminate IGRA results was also observed in a Californian study, which only included 17 confirmed cases with CNS disease [11]. Although the basis for these observations remains uncertain, it is tempting to hypothesise that age is a contributing factor, considering that the median age of our cohort was 2.6 years, but we did not detect an association between age and indeterminate test results in multivariate logistic regression analyses. Nevertheless, several published studies, including our own, have shown that young age is associated with indeterminate IGRA results [31–33]. Alternatively, there may be immunological differences between children with TBM and those with pulmonary TB, resulting in impaired IGRA performance in the former.

In accordance with published data our results show that acid-fast bacilli stain microscopy has very poor sensitivity in children with TBM [7, 14, 22]. Mycobacterial culture performed on CSF was the microbiological test with the highest sensitivity, but still only positive in half of the cases. PCR for M. tuberculosis performed on CSF had even lower sensitivity, producing a positive result in only approximately one in three cases. However, the fact that a variety of in-house and commercial PCR assays were used at different healthcare institutions limit the interpretation of this finding. A recent study that included 23 HIV-infected adults with TBM found that the recently released Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assay had higher sensitivity than both the previous generation Xpert MTB/RIF assay and culture (sensitivity 70% versus 43% and 43%, respectively) [34], suggesting that some commercial PCR-based assays may perform as well as culture or potentially even have superior sensitivity in TBM. However, larger prospective studies are needed to confirm those findings. Our data show that performing both culture and PCR on CSF in parallel increases the diagnostic yield, in concordance with observations in a paediatric study from South Africa [21]. A recent publication raises hopes that metagenomic next-generation sequencing of CSF could potentially improve the diagnosis of CNS infections with organisms that are difficult to detect with existing microbiological methods [35].

In addition, our data show that in the large majority of children with TBM at least one test produces a positive result if TST, IGRA, CSF culture and CSF PCR are performed in parallel, as only 15.6% of the cases showed false-negative results in all four tests. In the paediatric setting immunological tests are often used as adjunctive tests in suspected TB disease [8], a practice that is supported by our findings. Although positive immunological tests do not confirm TB disease, in a child with compatible clinical and radiological findings they lend substantial support to a putative diagnosis of TBM.

In a substantial number of children in this cohort M. tuberculosis was detected in samples other than CSF, helping to secure a microbiological diagnosis. Sputum, gastric aspirates and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples all had high yields, universally with a positive detection rate of ≥75%. However, considering that decisions to obtain those samples were made by clinicians managing the patients, rather than according to a standardised study protocol, it is probable that these samples were preferentially obtained in a selected group of patients who had chest radiography changes or respiratory symptoms. Nevertheless, our data highlight that testing respiratory/gastric samples should be undertaken routinely in children with suspected TBM, as M. tuberculosis can often not be detected in CSF, precluding microbiological confirmation and susceptibility testing.

As with all retrospective studies, a key limitation is that some data were missing due to incomplete documentation. A larger number of patients had TSTs performed, but only categorical rather than quantitative data were documented, resulting in those patients having to be excluded from some of the analyses. Additionally, only a small number of participating centres were using T-SPOT.TB assays; consequently, the data on the performance of this test were limited. No cases had IGRAs performed on CSF; however, a recent meta-analysis has shown that performing IGRAs on CSF rather than blood does not result in a higher diagnostic yield [12]. Finally, in common with all retrospective studies, there is a risk of recall bias and preferential reporting.

In conclusion, our data show that in the European setting children with TBM tend to present earlier and with less severe disease than in high TB incidence settings. A large proportion of children with TBM have coexisting intrathoracic TB disease, and consequently chest imaging and collection of respiratory or gastric samples should be considered in all patients with suspected TBM. Both immunological (TST and IGRAs) and microbiological TB tests have suboptimal sensitivity in children with TBM. Performing both TST and IGRA in parallel with microbiological testing of CSF by culture and PCR results in a substantial increase in the proportion of children who have evidence of TB infection, which should therefore be the standard approach in healthcare settings with sufficient resources to perform those tests.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02004-2019.Supplement (255KB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The ptbnet TB Meningitis Study Group: Matthias Bogyi, Wilhelminenspital Vienna, Austria; Carlotta Montagnani, Anna Meyer Children's University Hospital Florence, Italy; Laura Lancella, Bambino Gesù Children Hospital Rome, Italy; Eeva Salo, University of Helsinki Children's Hospital, Finland; Angeliki Syngelou, 2nd Dept of Paediatrics, National & Kapodistrian University of Athens, P. & A. Kyriakou Children's Hospital, Greece; Uros Krivec, University Children's Hospital Ljubljana, Slovenia; Andrea Martín Nalda and Antoni Soriano-Arandes, Hospital Vall d´Hebron Barcelona, Spain; Irene Rivero, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago de Compostela, Spain; Marta Benavides Nieto, Hospital Infantil Virgen del Rocío Sevilla, Spain; Mercedes Bueno, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón Madrid, Spain; Teresa del Rosal, Hospital Infantil La Paz Madrid, Spain; Luis Mayol and Borja Guarch, Hospital Universitari Dr Josep Trueta Girona, Spain; Jose Antonio Couceiro, Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra, Spain; Carmelo Guerrero Laleona, Hospital Miguel Servet Zaragoza, Spain; Rutger Bennet, Astrid Lindgren Children's Hospital Stockholm, Sweden; Karsten Kötz, Queen Silvia Children's Hospital Gothenburg, Sweden; Brittany Raffa, Evelina London Children's Hospital, UK; Fiona Shackley, Sheffield Children's Hospital, UK.

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

Author contributions: S. Thee and R. Krüger conceived of the study. R. Basu Roy, S. Thee, D. Blázquez-Gamero, B. Santiago-Garcia, M. Tsolia, R. Krüger and M. Tebruegge designed the study, collected the data and performed the data analyses. L. Falcón-Neyra, O. Neth, A. Noguera-Julian, C. Lillo, L. Galli, E. Venturini, D. Buonsenso, F. Götzinger, N. Martinez-Alier, S. Velizarova, F. Brinkmann and S.B. Welch contributed data, reviewed the data and provided input. All authors and collaborators have reviewed the paper and provided comments, and have approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest: R. Basu Roy was a consultant for FIND, Geneva, a non-profit organization, from 2014 to 2016.

Conflict of interest: S. Thee has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Blázquez-Gamero has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Falcón-Neyra has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: O. Neth has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Noguera-Julian has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: C. Lillo has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Galli has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E. Venturini has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Buonsenso has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Götzinger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N. Martinez-Alier has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Velizarova has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: F. Brinkmann has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S.B. Welch has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Tsolia has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Santiago-Garcia has received diagnostic assays free of charge for other projects from Cepheid, and support for conference attendance from GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflict of interest: R. Krüger has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Tebruegge has received QuantiFERON assays at reduced pricing or free of charge for other TB diagnostics projects from the manufacturer (Cellestis/Qiagen), and has received support for conference attendance from Cepheid.

Support statement: This project was carried out without dedicated funding. ptbnet is supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. M. Tebruegge was supported by a Clinical Lectureship provided by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and by a grant from the Technology Strategy Board/Innovate UK. B. Santiago-Garcia is funded by Spanish Ministry of Health – Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-funded by the European Union (FEDER) (Contrato Juan Rodés, grant JR16/00036). R. Basu Roy is funded by an NIHR Academic Clinical Lectureship at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. A. Noguera-Julian was supported by “Subvencions per a la Intensificació de Facultatius Especialistes” (Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya, Programa PERIS 2016–2020) (SLT008/18/00193). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report 2018. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollo V, Beauté J, Ködmön C, et al. Tuberculosis notification rate decreases faster in residents of native origin than in residents of foreign origin in the EU/EEA, 2010 to 2015. Euro Surveill 2017; 22: 30486. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.12.30486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 803–812. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70138-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solomons RS, Visser DH, Marais BJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a uniform research case definition for TBM in children: a prospective study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016; 20: 903–908. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miftode EG, Dorneanu OS, Leca DA, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in children and adults: a 10-year retrospective comparative analysis. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0133477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farinha NJ, Razali KA, Holzel H, et al. Tuberculosis of the central nervous system in children: a 20-year survey. J Infect 2000; 41: 61–68. doi: 10.1053/jinf.2000.0692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiang SS, Khan FA, Milstein MB, et al. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 947–957. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70852-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tebruegge M, Ritz N, Curtis N, et al. Diagnostic tests for childhood tuberculosis: past imperfect, present tense and future perfect? Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34: 1014–1019. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tebruegge M, Ritz N, Koetz K, et al. Availability and use of molecular microbiological and immunological tests for the diagnosis of tuberculosis in Europe. PLoS One 2014; 9: e99129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villanueva P, Neth O, Ritz N, et al. Use of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra assays among paediatric tuberculosis experts in Europe. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1800346. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00346-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kay AW, Islam SM, Wendorf K, et al. Interferon-γ release assay performance for tuberculosis in childhood. Pediatrics 2018; 141: e20173918. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Wang ZJ, Chen LH, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of interferon-γ release assays for tuberculous meningitis: a meta-analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016; 20: 494–499. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Well GT, Paes BF, Terwee CB, et al. Twenty years of pediatric tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort study in the western cape of South Africa. Pediatrics 2009; 123: e1–e8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bang ND, Caws M, Truc TT, et al. Clinical presentations, diagnosis, mortality and prognostic markers of tuberculous meningitis in Vietnamese children: a prospective descriptive study. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 573. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1923-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tebruegge M, Bogyi M, Soriano-Arandes A, et al. Shortage of purified protein derivative for tuberculosis testing. Lancet 2014; 384: 2026. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62335-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noguera-Julian A, Calzada-Hernández J, Brinkmann F, et al. Tuberculosis disease in children and adolescents on therapy with antitumor necrosis factor-α agents: a collaborative, multicenter Paediatric Tuberculosis Network European Trials Group (ptbnet) study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; in press doi:10.1093/cid/ciz1138.doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marais BJ, Heemskerk AD, Marais SS, et al. Standardized methods for enhanced quality and comparability of tuberculous meningitis studies. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64: 501–509. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thwaites GE, Tran TH. Tuberculous meningitis: many questions, too few answers. Lancet Neurol 2005; 4: 160–170. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70019-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nabukeera-Barungi N, Wilmshurst J, Rudzani M, et al. Presentation and outcome of tuberculous meningitis among children: experiences from a tertiary children's hospital. Afr Health Sci 2014; 14: 143–149. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i1.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaya S, Dangor Z, Solomon F, et al. Incidence of tuberculosis meningitis in a high HIV prevalence setting: time-series analysis from 2006 to 2011. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016; 20: 1457–1462. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomons RS, Visser DH, Friedrich SO, et al. Improved diagnosis of childhood tuberculous meningitis using more than one nucleic acid amplification test. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 74–80. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Günes A, Uluca Ü, Aktar F, et al. Clinical, radiological and laboratory findings in 185 children with tuberculous meningitis at a single centre and relationship with the stage of the disease. Ital J Pediatr 2015; 41: 75. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0186-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solomons RS, Goussard P, Visser DH, et al. Chest radiograph findings in children with tuberculous meningitis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015; 19: 200–204. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tebruegge M, Dutta B, Donath S, et al. Mycobacteria-specific cytokine responses detect tuberculosis infection and distinguish latent from active tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 485–499. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0059OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manyelo CM, Solomons RS, Snyders CI, et al. Potential of host serum protein biomarkers in the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis in children. Front Pediatr 2019; 7: 376. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudbury EL, Otero L, Tebruegge M, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific cytokine biomarkers for the diagnosis of childhood TB in a TB-endemic setting. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2019; 16: 100102. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Connell TG, Ritz N, Paxton GA, et al. A three-way comparison of tuberculin skin testing, QuantiFERON-TB gold and T-SPOT.TB in children. PLoS One 2008; 3: e2624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kampmann B, Whittaker E, Williams A, et al. Interferon-γ release assays do not identify more children with active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 1374–1382. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00153408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsolia MN, Mavrikou M, Critselis E, et al. Whole blood interferon-γ release assay is a useful tool for the diagnosis of tuberculosis infection particularly among Bacille Calmette Guèrin-vaccinated children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29: 1137–1140. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181ebfe8a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laurenti P, Raponi M, de Waure C, et al. Performance of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of confirmed active tuberculosis in immunocompetent children: a new systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 131. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1461-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tebruegge M, de Graaf H, Sukhtankar P, et al. Extremes of age are associated with indeterminate QuantiFERON-TB gold assay results. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 2694–2697. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00814-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connell TG, Tebruegge M, Ritz N, et al. Indeterminate interferon-γ release assay results in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2010; 29: 285–286. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181c4822f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Velasco-Arnaiz E, Soriano-Arandes A, Latorre I, et al. Performance of tuberculin skin tests and interferon-γ release assays in children younger than 5 years. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018; 37: 1235–1241. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahr NC, Nuwagira E, Evans EE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected adults: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18: 68–75. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30474-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson MR, Sample HA, Zorn KC, et al. Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 2327–2340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-02004-2019.Supplement (255KB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-02004-2019.Shareable (283.4KB, pdf)