Abstract

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (SPD), also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare, relapsing, sterile pustular eruption of unknown etiology that develops most commonly in middle-aged or mature women. This article reviews the presentation, associations, and management of the condition and highlights advances in pathophysiology. Onset of SPD during pregnancy has not been reported. Herein, we report a case of SPD that developed during pregnancy. The patient was treated with dapsone without complications for her or the fetus. An association between T helper (Th) 17 and Th2 environments in the development of SPD has been advocated. Pregnancy is characterized by a predominance of Th2 responses and increased interleukin-17 levels and thus may favor the development of the condition

Keywords: Subcorneal pustular dermatosis, Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, Neutrophilic dermatosis, Pregnancy, Dapsone, Gestation

Introduction

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (SPD), also known as Sneddon-Wilkinson disease, is a rare, benign, yet relapsing pustular dermatosis that was first described by Sneddon and Wilkinson in 1956 (Sneddon and Wilkinson, 1979). Herein, we review the presentation, associations, pathophysiology, and management of SPD. Furthermore, we present a unique case of SPD that developed during pregnancy and discuss possible etiopathogenetic mechanisms in our patient.

Epidemiology

The incidence of SPD is unknown. More than 200 cases were reported in a review published in 1981 (Chimenti and Ackerman, 1981). Racial predilection and geographic distribution have not been reported. SPD is more common in females than in males (ratio 4:1) and has been rarely reported in children (Liao et al., 2002, Naik and Cowen, 2013, Scalvenzi et al., 2013). SPD usually presents between the fifth and seventh decades of life (Naik and Cowen, 2013).

Clinical and histopathologic features

SPD is a relapsing, symmetrical eruption that favors the trunk, intertriginous areas (especially the axillae), and flexural aspects of the extremities. The palms and soles are exceptionally affected whereas the face and mucous membranes are spared. Atypical cases in terms of age, sex, or site distribution (e.g., distal extremities) have been reported (Boyd and Stroud, 1991). The eruption presents abruptly with or without pain and in some cases with pruritic papules that develop into flaccid pustules, vesicles, or occasionally bullae (Watts and Khachemoune, 2016). Pea-sized pustules arise on normal skin or a slightly erythematous base (Cheng et al., 2008). The bottom half of the pustule contains purulent material, whereas the top half contains clear fluid (hypopyon pustule). Lesions spread and coalesce within a day or two to form annular or serpiginous patterns with central clearing and peripheral pustules (Naik and Cowen, 2013). The bullae are flaccid and rupture easily, thus forming superficial crusts and scales. They heal often with mild hyperpigmentation. The lesions are mildly pruritic and not usually associated with constitutional symptoms; however, cases presenting with malaise, fever, or arthralgias have been reported (Prat et al., 2014, Razera et al., 2011).

The salient histologic feature is the subcorneal accumulation of neutrophils with the absence of spongiosis or acantholysis, although older lesions may show the latter (Cheng et al., 2008). Pustules appear to sit on top of the epidermis, and the epidermis beneath the pustule shows minimal change (i.e., neutrophils in transit and occasionally slight intercellular edema). Early lesions show a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with neutrophils and occasional eosinophils.

Associations

SPD has been associated with a wide spectrum of systemic disorders, including neutrophilic dermatoses, hematologic disorders, solid organ malignancies, connective tissue disorders, thyroid disorders, drugs, and infections (Watts and Khachemoune, 2016). It has been related to neutrophic dermatoses, including pyoderma gangrenosum (Scerri et al., 1994), and inflammatory bowel disorders (i.e., Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis; Delaporte et al., 1992, Sutton et al., 2013).

Numerous hematologic disorders, including aplastic anemia (Park et al., 1998), lymphomas (Ratnarathorn and Newman, 2008), multiple myeloma (Hensley and Caughman, 2000), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Brown et al., 2003, Wallach and Vignon-Pennamen, 2006), IgG cryoglobulinemia (Sneddon and Wilkinson, 1979), and monoclonal gammopathies, especially IgA myeloma, have been associated with SPD and may occur years after SPD onset (Dallot et al., 1988, Kasha and Epinette, 1988). Hence, screening for paraproteinemia is required to rule out myeloma in case of SPD, and periodic screening in patients who test initially negative has been recommended (Lutz et al., 1998). Solid organ malignancies, which have been reported in patients with SPD, include metastatic thymoma, apudoma, and epidermoid carcinoma of the lung (Hensley and Caughman, 2000, Moschella and Davis, 2012, Wallach and Vignon-Pennamen, 2006).

Connective tissue disorders, such as Sjogren’s syndrome (Tsuruta et al., 2005), systemic lupus erythematosus, synovitis/acne/pustulosis/hyperostosis/osteitis (SAPHO) syndrome (Scarpa et al., 1997), and rheumatoid arthritis (both sero-positive and sero-negative; Butt and Burge, 1995) have been associated with SPD. Other associated conditions include hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism (Taniguchi et al., 1995), and multiple sclerosis (Kohler et al., 1999). Drugs that can induce reactions that present with SPD-like features include multikinase inhibitors (sorafenib; Tajiri et al., 2015), gefitinib (Sheen et al., 2008), paclitaxel (Weinberg et al., 1997), isoniazid (Yamasaki et al., 1985), amoxicillin (Shuttleworth, 1989), and cefazolin sodium (Stough et al., 1987). A therapeutic paradox has been reported of a dapsone-induced occurrence of subcorneal pustules in an earlier SPD case (Halevy et al., 1983). In a similar way, adalimumab can both treat and trigger SPD (Sauder and Glassman, 2013, Versini et al., 2013). Lesions at the injection site of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor have developed, possibly secondary to the drug’s chemotactic effect (Lautenschlager et al., 1994).

SPD can be aggravated and linked with various infections, most importantly a Mycoplasma pnemoniae infection (Bohelay et al., 2015, Lombart et al., 2014, Papini et al., 2003, Winnock et al., 1996), primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis (Iyengar et al., 2015), and urinary tract infection. Echocardiography is a rare chemotactic stimulator, and incidents have been reported of subcorneal pustules that developed 10 to 12 hours after the procedure (Ingber et al., 1983).

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of the condition has not been fully elucidated and its nosological classification remains controversial (Razera et al., 2011). Neutrophil migration through the epidermis indicates the presence of chemotactic factors in the upper epidermis (Cheng et al., 2008). Various factors have been detected inside the subcorneal vesicles, namely tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, IL-8, C5a, and IgA. An increase in IL-1b has been noted when pustulosis reappeared (Bonifati et al., 2005). IL-1b is an activator of TNF-alpha, suggesting that it may play a role in the pathogenesis of SPD. The role of TNF-alpha in the pathogenesis of the condition is supported by the response of SPD to TNF-alpha blockers, such as adalimumab (Abreu Velez et al., 2011, Grob et al., 1991, Razera et al., 2011). Neutrophil priming has been suggested as a consequence of excessive production of TNF-alpha by keratinocytes, or monocytes may be crucial to the pathogenesis (Grob et al., 1991).

Serum levels of thymus and activation regulated chemokine/chemokine ligand 17 are elevated, which suggests a Th2 response (Ono et al., 2013a, Ono et al., 2013b). A very strong association has been found with HLA-DPDQDR, CD68, mast cell tryptase, and 70 kDa zeta-associated protein in the subcorneal pustules and surrounding blood vessels (Abreu Velez et al., 2011). The same study detected S6-pS240 (an antiribosomal protein) adjacent to the subcorneal blister. The authors suggested a possible genetic component underlying a restricted immune response.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of SPD includes pustular psoriasis, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), pemphigus foliaceus, dermatitis herpetiformis, impetigo, subcorneal type of IgA pemphigus, amicrobial pustulosis, and genetic syndromes characterized by pustule formation such as pyogenic arthritis/pyoderma gangrenosum/acne and SAPHO. Some authors maintain that SPD is closely related to pustular psoriasis (Sanchez et al., 1983). However, typical histopathologic features of pustular psoriasis, such as psoriasiform hyperplasia, parakeratosis, and spongiform pustules, are not noted in SPD. AGEP is a sudden, self-limited eruption typically triggered by a drug or infection. It shows generalized minute pustules similar to those noted in SPD. The presence of systemic symptoms, eosinophilia, marked edema of the papillary dermis, keratinocyte necrosis, mixed neutrophil-rich interstitial, and mid-dermal infiltrates with eosinophils in the pustules or dermis sets AGEP apart from SPD (Watts and Khachemoune, 2016).

Pemphigus foliaceus typically shows seborrheic distribution (i.e., affecting sites such as the scalp, face, upper chest, and upper back). The lesions never coalesce in annular fashion, which distinguishes pemphigus foliaceus from SPD. Dermatitis herpetiformis has lesions that are intensely pruritic, unlike SPD, and found over the extensor surfaces. Lesions of bullous impetigo are mildly tender and associated with inflammation. Gram-positive cocci are detected in the bullae. Whether SPD cases with epidermal IgA deposits define a subset of SPD or a pemphigus variant that is otherwise indistinguishable from classic SPD remains a matter of debate (Trautinger and Hönigsman, 2012).

Lesions in amicrobial pustulosis show a different distribution than those in SPD, and the histopathology of the condition shows spongiform pustules with acanthosis and parakeratosis (Boms and Gambichler, 2006). Pyogenic arthritis/pyoderma gangrenosum/acne and SAPHO syndromes present early in life and can be easily differentiated from SPD on the basis of their distinct clinicopathologic features.

Treatment

Dapsone (50–100 mg/day) is the drug of choice (Maalouf et al., 2015, Naik and Cowen, 2013). A response to dapsone is typical of SPD and has been used to suggest a diagnosis of SPD (Cheng et al., 2008). Lesions resolve within 1 to 4 weeks of treatment, but maintenance at a lower dosage is required to prevent relapses. Other drugs, such as cochicine and sulfapyridine, that have antineutrophilic effects have been effective (Cohen, 2009, Naik and Cowen, 2013) and can be used as second-line treatment. Oral retinoids (i.e., acitretin and etretinate) have also been used successfully (Marlière et al., 1999, Razera et al., 2011) with a quick response (symptoms resolve within 8–15 days of treatment) and good tolerability. As with dapsone, maintenance at low doses is required to prevent recurrence (Cohen, 2009). Potent topical and oral corticosteroids can be safely used alone or in combination with dapsone (Kalia and Adams, 2007, Naik and Cowen, 2013, Razera et al., 2011). These agent are a great choice when patients present either with concomitant dermatologic conditions or associated systemic symptoms (Cohen, 2009, Ranieri et al., 2009).

Psoralen with ultraviolet light A (PUVA; Khachemoune and Blyumin, 2003, Marlière et al., 1999) and narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB; Orton and George, 1997) can work as solo therapies in SPD. A remarkably quick response has been observed when PUVA was combined with dapsone (Bauwens et al., 1999). Several cases were treated with UVB alone or combined with minocycline (Cameron and Dawe, 1997, Park et al., 1986). One case was treated successfully with PUVA, but a maintenance regimen with a combination of retinoid and narrowband UVB did not prevent relapses (Orton and George, 1997).

Biologic agents, such as adalimumab (Versini et al., 2013), infliximab (Bonifati et al., 2005), and etanercept (Berk et al., 2009), have been used in challenging cases. Adjunctive treatment with corticosteroid and/or retinoid (Berk et al., 2009, Iobst and Ingraham, 2005, Voigtländer et al., 2001) is often needed. Cases that have not responded to these therapies have been treated with vitamin E, tetracycline, estrogen, chloramphenicol, niacin, tacalcitol, and methotrexate (Boyd and Stroud, 1991, Kawaguchi et al., 2000).

Finally, treating or controlling the associated condition has helped to achieve clinical resolution. SPD with concomitant rheumatoid arthritis was managed with dapsone and hydroxychloroquine (Butt and Burge, 1995), minocycline, and narrowband UVB (Cameron and Dawe, 1997), or etanercept (Berk et al., 2009).

Case report

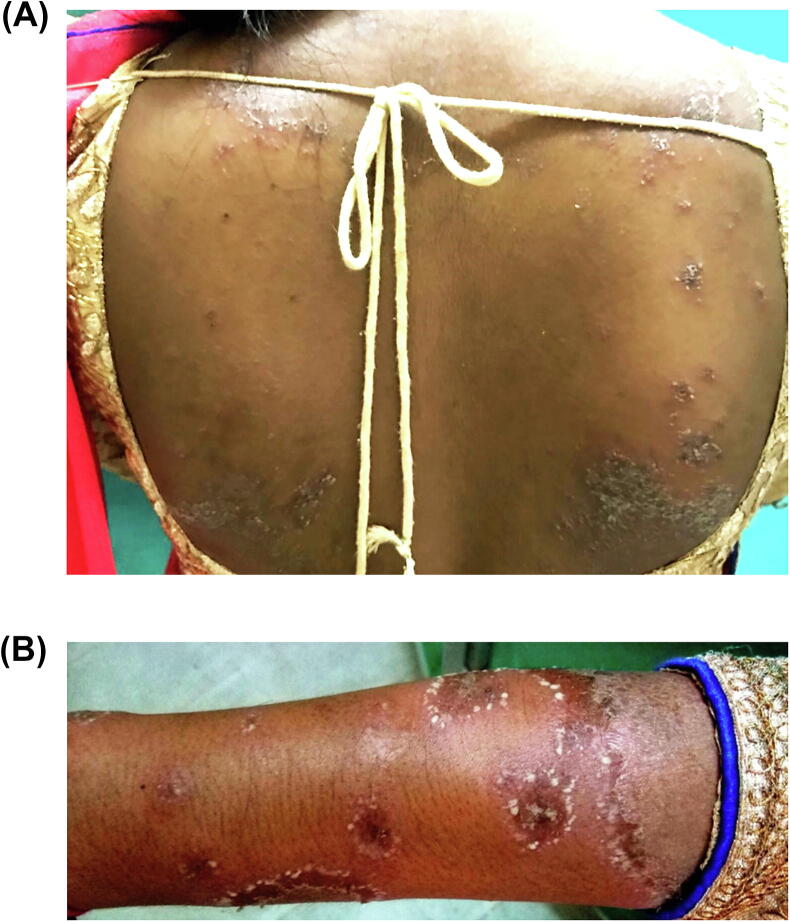

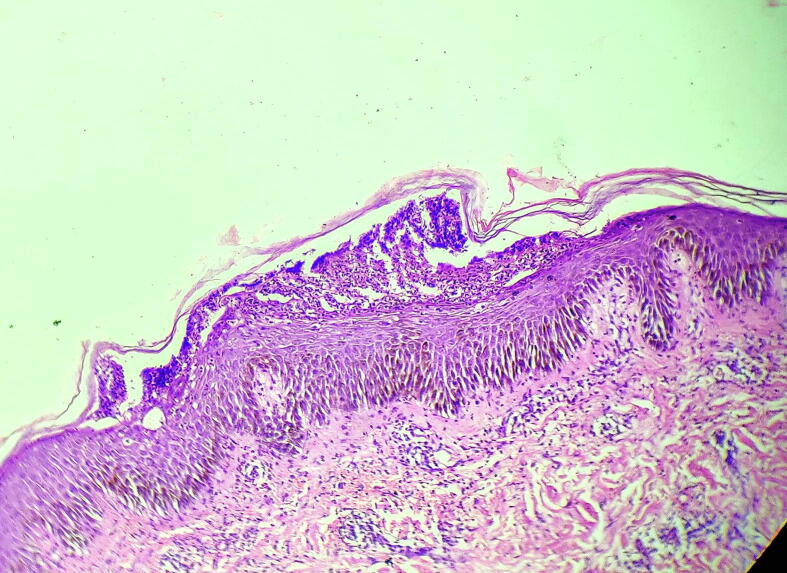

A 26-year-old primigravida presented in the third month of gestation with pustular lesions over the trunk, intertriginous areas, and extremities of 2 months’ duration (Fig. 1A). There were no similar complaints prior to the pregnancy and no personal or family history of psoriasis or other skin disease. There was no medication intake. Clinical examination revealed multiple nontender, flaccid vesiculo-pustules measuring 2 to 10 mm arranged in annular, circinate, and serpiginous patterns that ruptured to form superficial crusts and scaly lesions on erythematous background (Fig. 1A and B). Testing for Nikolsky sign was negative. Histopathology testing revealed a subcorneal pustule with numerous neutrophils, neutrophils infiltrating in the epidermis (neutrophils in transit), mild intercellular edema, and a dermal perivascular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with neutrophils (Fig. 2). Bacterial and fungal stains and cultures from pustules also tested negative, and testing ruled out infections such as urinary tract infection. Serologic tests, including complete blood count, reticulocyte count, liver and renal blood tests, and serum chemistries including calcium, were within the normal range with the exception of low hemoglobin (10.1 gm/dl). There was no paraproteinemia, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase level was normal.

Fig. 1.

(A) Crusted erythematous plaques with superimposed pustules on the back, as well as discrete, isolated, pea-sized pustules. (B) Closeup view of minute pustules at the rim of round or annular, scaly, erythematous plaques on the forearm.

Fig. 2.

Immediately below a normal stratum corneum is a blister cavity containing numerous neutrophils. The epidermis below the blister shows sparse neutrophils in transit and mild intercellular edema (spongiosis). Lesional skin adjacent to the pustule shows intact granular layer. Dermis shows a neutrophil and lymphocytic infiltrate (hematoxylin and eosin, 10×).

A diagnosis of SPD was made based on the constellation of clinical and histopathologic findings. The patient was started on dapsone 100 mg daily and clobetasol propionate 0.05% cream twice daily. The lesions healed with hyperpigmentation in 3 to 4 weeks. The patient was followed up monthly until delivery, and no relapses were noted. The pregnancy was otherwise uneventful and resulted in a healthy newborn.

Discussion

Pregnancy is associated with aggravation, and less often improvement, of inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis. Pregnancy may also trigger a flare of pustular psoriasis (impetigo herpetiformis [IH]) in a genetically predisposed individual (Vaidya et al., 2013a). A Th1 to Th2 shift that occurs during gestation may be related to deterioration of inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis during pregnancy (Koutroulis et al., 2011). Neutrophilic dermatoses, such as pyoderma gangrenosum, sweet syndrome, and Behcet disease, can flare or present during gestation (Brooks et al., 2013).

Herein, we report on a case of SPD with onset during pregnancy. Our literature review did not reveal any similar cases.

The differential diagnosis in our case includes pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (IH) and AGEP. IH typically occurs in the third trimester, often with systemic features, and can be associated with hypocalcemia or low serum levels of vitamin D (Vaidya et al., 2013b). These features were absent in our case. In addition, the half-half appearance of some flaccid vesiculopustules (hypopyon pustules) in our case is characteristic of SPD. Furthermore, histopathologic features of IH, such as spongiform pustules, psoriasiform hyperplasia, and parakeratosis, were absent in our case. Lesional skin adjacent to the pustule showed absence of parakeratosis, absence of psoriasiform hyperplasia, and intact granular layer, which are features that rule out IH.

Our patient responded promptly to treatment with dapsone, which supports the diagnosis of SPD, especially because dapsone treatment of IH has not been reported and there is only one case report with oral dapsone treatment for generalized pustular psoriasis in an adult nonpregnant patient (evidence level III; Sheu et al., 2016). Improvement in this patient was noted after 1 month of dapsone treatment, and the disease was then controlled while also on acitretin. This contrasts the dramatic response of SPD to dapsone, which has been used to suggest a diagnosis of SPD (Cheng et al., 2008). Our patient was not on any medications that could cause AGEP, and features of AGEP such as fever, eosinophilia, marked edema of the papillary dermis, and mixed infiltrate with conspicuous eosinophils, exocytosis of eosinophils, and single-cell keratinocyte necrosis were absent in our case.

Neutrophilic dermatoses such as SPD are considered to be induced by IL-8, which attracts neutrophils (Keller et al., 2005). The production of IL-8 is stimulated by IL-17–producing cells, such as Th17 cells (Nakamizo et al., 2010). Th17 may be involved in the pathogenesis of Th2-dominant atopic dermatitis (Koga et al., 2008). A case of SPD exhibited a high serum thymus and activation-regulated chemokine/chemokine ligand 17 level, thereby raising the possibility of a Th2 association (Ono et al., 2013a, Ono et al., 2013b). The researchers suggested that a Th17 and Th2 association is involved in the pathogenesis of SPD. As mentioned, a Th1 to Th2 shift occurs during pregnancy; additionally, IL-17 levels increase during gestation (Kaminski et al., 2018). These immunologic changes may favor development of SPD during pregnancy.

Our patient responded promptly to dapsone, which supports the diagnosis of SPD. Despite the low hemoglobin level prior to treatment, the patient tolerated dapsone treatment well and her hemoglobin levels did not fall further. Normal pregnancy outcomes have been reported with dapsone, and the drug does not present a significant risk to the fetus. Therefore, the medication should be promptly administered during pregnancy for skin diseases such as SPD and dermatitis herpetiformis that typically respond to the drug. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia has been attributed to dapsone treatment during pregnancy (Thornton and Bowe, 1989). However, the risk of hyperbilirubinemia in the neonate is negligible if dapsone is discontinued 4 weeks prior to delivery (Thornton and Bowe, 1989).

Conclusion

We report on a rare case of SPD that developed during pregnancy. We highlight the importance of identifying this rare presentation to guide prompt treatment. The differential diagnosis of such cases requires dermatologic expertise; therefore, generalized pustular eruptions should be referred to dermatology. Treatment with dapsone should be administered promptly and can be tolerated well during gestation.

Financial disclosures

None.

Funding

None.

Study approval

N/A.

Footnotes

Financial disclosures: none.

Funding: none.

Study approval: N/A.

For patient information on skin cancer in women, please click on Supplemental Material to bring you to the Patient Page. Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100541.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abreu Velez A.M., Smith J.G., Jr, Howard M.S. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis an immunohistopathological perspective. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011;4(5):526–529. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwens M., De Coninck A., Roseeuw D. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis treated with PUVA therapy. A case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1999;198(2):203–205. doi: 10.1159/000018113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk D.R., Hurt M.A., Mann C., Sheinbein D. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease treated with etanercept: Report of two cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34(3):347–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohelay G., Duong T.A., Ortonne N., Chosidow O., Valeyrie-Allanore L. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis triggered by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: a rare clinical association. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(5):1022–1025. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boms S., Gambichler T. Review of literature on amicrobial pustulosis of the folds associated with autoimmune disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7(6):369–374. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati C., Trento E., Cordiali Fei P., Muscardin L., Amantea A., Carducci M. Early but not lasting improvement of recalcitrant subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) after infliximab therapy: relationships with variations in cytokine levels in suction blister fluids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30(6):662–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2005.01902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd A.S., Stroud M.B. Vesiculopustules of the thighs and abdomen. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) Arch Dermatol. 1991;127(10):1571–1574. doi: 10.1001/archderm.127.10.1571b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks J., Cunha P.R., Kroumpouzos G. Miscellaneous skin disease. In: Kroumpouzos G., editor. Text Atlas of Obstetric Dermatology. Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers; Philadelphia: 2013. pp. 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.J., Barrett P.D., Hendrick A., Langtry J.A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in association with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83(4):306–307. doi: 10.1080/00015550310016661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt A., Burge S.M. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease in association with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(2):313–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron H., Dawe R.S. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) treated with narrowband (TL-01) UVB phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(1):150–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Edmonds E., Ben-Gashir M., Yu R.C. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: 50 years on. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(3):229–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimenti S., Ackerman A.B. Is subcorneal pustular dermatosis of Sneddon and Wilkinson an entity sui generis? Am J Dermatopathol. 1981;3(4):363–376. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198100340-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P.R. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(5):301–312. doi: 10.2165/11310730-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallot A., Decazes J.M., Drouault Y., Rybojad M., Verola O., Morel P. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) with amicrobial lymph node suppuration and aseptic spleen abscesses. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(6):803–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaporte E., Colombel J.F., Nguyen-Mailfer C., Piette F., Cortot A., Bergoend H. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72(4):301–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grob J.J., Mege J.L., Capo C., Jancovicci E., Fournerie J.R., Bongrand P. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Sneddon-Wilkinson subcorneal pustular dermatosis. A model of neutrophil priming in vivo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(5 Pt 2):944–947. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70290-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy S., Ingber A., Feuerman E.J. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis–an unusual course. Acta Derm Venereol. 1983;63(5):441–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley C.D., Caughman S.W. Neutrophilic dermatoses associated with hematologic disorders. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18(3):355–367. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(99)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber A., Ideses C., Halevy S., Feuerman E.J. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) after a diagnostic echogram. Report of two cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9(3):393–396. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iobst W., Ingraham K. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(12):3771. doi: 10.1002/art.21402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S., Chambers C.J., Chang S., Fung M.A., Sharon V.R. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis associated with Coccidioides immitis. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21(8):3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia S., Adams S. Can you identify this skin condition? Sneddon– Wilkinson disease. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(1):37–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski V.L., Ellwanger J.H., Matte M.C.C., Savaris R.F., Vianna P., Chies J.A.B. IL-17 blood levels increase in healthy pregnancy but not in spontaneous abortion. Mol Biol Rep. 2018;45(5):1565–1568. doi: 10.1007/s11033-018-4268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasha E.E., Epinette W.W. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in association with a monoclonal IgA gammopathy. A report and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(5 Pt 1):854–858. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi M., Mitsuhashi Y., Kondo S. A case of subcorneal pustular dermatosis treated with tacalcitol (1alpha, 24-dihydroxyvitaminD3) J Dermatol. 2000;27(10):669–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2000.tb02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller M., Spanou Z., Schaerli P., Britschgi M., Yawalkar N., Seitz M. T cell-regulated neutrophilic inflammation in autoinflammatory diseases. J Immunol. 2005;175:7678–7686. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khachemoune A., Blyumin M.L. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease resistant to dapsone and colchicine successfully controlled with PUVA. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9(5):24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga C., Kabashima K., Shiraishi N., Kobayashi M., Tokura Y. Possible pathogenic role of Th17 cells for atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(11):2625–2630. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler L.D., Mohrenschlager M., Worret W.I., Ring J. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Snedden–Wilkinson disease) in a patient with multiple sclerosis. Dermatology. 1999;199:69–70. doi: 10.1159/000018185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutroulis I., Papoutsis J., Kroumpouzos G. Atopic dermatitis in pregnancy: current status and challenges. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66(10):654–663. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e31823a0908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenschlager S., Itin P.H., Hirsbrunner P., Büchner S.A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis at the injection site of recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in a patient with IgA myeloma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30(5 Pt 1):787–789. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P.B., Rubinson R., Howard R., Sanchez G., Frieden I.J. Annular pustular psoriasis–most common form of pustular psoriasis in children: report of three cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19(1):19–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombart F., Dhaille F., Lok C., Dadban A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(3):e85–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz M.E., Daoud M.S., McEvoy M.T., Gibson L.E. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a clinical study of ten patients. Cutis. 1998;61(4):203–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf D., Battistella M., Bouaziz J.D. Neutrophilic dermatosis: disease mechanism and treatment. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22(1):23–29. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlière V., Beylot-Barry M., Beylot C., Doutre M. Successful treatment of subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-wilkinson disease) by acitretin: report of a case. Dermatology. 1999;199(2):153–155. doi: 10.1159/000018224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschella S.M., Davis D.P.D. Neutrophilic dermatoses. In: Bologna J.L., Jorizzo J.L., Schaffer J.V., editors. Dermatology. Saunders; London: 2012. pp. 423–438. [Google Scholar]

- Naik H.B., Cowen E.W. Autoinflammatory pustular neutrophilic diseases. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31(3):405–425. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamizo S., Kobayashi S., Usui T., Miyachi Y., Kabashima K. Clopidogrel-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with elevated Th17 cytokine levels as determined by a drug lymphocyte stimulation test. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(6):1402–1403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S., Otsuka A., Miyachi Y., Kabashima K. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis exhibiting a high serum TARC/CCL17 level. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5(1):38–42. doi: 10.1159/000348241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono S., Nakajima S., Otsuka A., Miyachi Y., Kabashima K. Pigmented purpuric dermatitis with high expression levels of serum TARC/CCL17 and epidermal TSLP. Eur J Dermatol. 2013;23(5):701–702. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orton D.I., George S.A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis responsive to narrowband (TL-01) UVB phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(1):149–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papini M., Cicoletti M., Landucci P. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis and mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory infection. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83(5):387–388. doi: 10.1080/00015550310010630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B.S., Cho K.H., Eun H.C., Youn J.I. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in a patient with aplastic anemia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(2 Pt 1):287–289. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.K., Park H.Y., Bang D.S., Cho C.K. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis treated with phototherapy. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25(2):124–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1986.tb04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat L., Bouaziz J.D., Wallach D., Vignon-Pennamen M.D., Bagot M. Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(3):376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri P., Bianchetti A., Trabucchi M. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease: a case report of a rare disease in a nonagenarian. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1322–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnarathorn M., Newman J. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) occurring in association with nodal marginal zone lymphoma: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14(8):6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razera F., Olm G.S., Bonamigo R.R. Neutrophilic dermatoses: Part II. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(2):195–209. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez N.P., Perry H.O., Muller S.A., Winkelmann R.K. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis and pustular psoriasis. A clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119(9):715–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauder M.B., Glassman S.J. Palmoplantar subcorneal pustular dermatosis following adalimumab therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(5):624–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scalvenzi M., Palmisano F., Annunziata M.C., Mezza E., Cozzolino I., Costa C. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in childhood: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/424797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa R., Lubrano E., Cozzi R., Ames P.R., Oriente C.B., Oriente P. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease). Another cutaneous manifestation of SAPHO syndrome? Br J Rheum. 1997;36(5):602–603. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/36.5.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen Y.S., Hsiao C.H., Chu C.Y. Severe purpuric xerotic dermatitis associated with gefitinib therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(2):269–270. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu J.S., Divito S.J., Enamandram M., Merola J.F. Dapsone therapy for pustular psoriasis: case series and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2016;232(1):97–101. doi: 10.1159/000431171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneddon I.B., Wilkinson D.S. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1979;100(1):61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuttleworth D. A localized, recurrent pustular eruption following amoxycillin administration. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14(5):367–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stough D., Guin J.D., Baker G.F., Haynie L. Pustular eruptions following administration of cefazolin: a possible interaction with methyldopa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16(5 Pt 1):1051–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)80416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton A.M., Lawrence H.S., Canty K.M. Crohn's disease presenting as a neutrophilic dermatosis in a 5-month-old boy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(5):619–620. doi: 10.1111/pde.12156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi S., Tsuruta D., Kutsuna H., Hamada T. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis in a patient with hyperthyroidism. Dermatology. 1995;190(1):64–66. doi: 10.1159/000246638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajiri K., Nakajima T., Kawai K., Minemura M., Sugiyama T. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease induced by sorafenib in a patient with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Intern Med. 2015;54(6):597–600. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Y.S., Bowe E.T. Neonatal hyperbilirubinemia after treatment of maternal leprosy. South Med J. 1989;82:668. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198905000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautinger F., Hönigsman H. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis. In: Goldsmith L.A., Katz S.I., Gilchrest B., Paller A.S., Leffell D.J., Wolff K., editors. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2012. pp. 383–385. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuruta D., Matsumura-Oura A., Ishii M.L. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis and Sjogren’s syndrome. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(11):55–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya D., Itkin A., Kroumpouzos G. Impetigo herpetiformis. In: Kroumpouzos G., editor. Text Atlas of Obstetric Dermatology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 2013. pp. 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya D.C., Kroumpouzos G., Bercovitch L. Recurrent postpartum impetigo herpetiformis presenting after a “skip” pregnancy. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2013;93(1):102–103. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versini M., Mantoux F., Angeli K., Passeron T., Lacour J.P. Sneddon-Wilkinson disease: efficacy of intermittent adalimumab therapy after lost response to infliximab and etanercept. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2013;140(12):797–800. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigtländer C., Lüftl M., Schuler G., Hertl M. Infliximab (anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody): a novel, highly effective treatment of recalcitrant subcorneal pustular dermatosis (Sneddon-Wilkinson disease) Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(12):1571–1574. doi: 10.1001/archderm.137.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts P., Khachemoune A. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis: a review of 30 years of progress. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17(6):653–671. doi: 10.1007/s40257-016-0202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallach D., Vignon-Pennamen M.D. From acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis to neutrophilic disease: Forty years of clinical research. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(6):1066–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg J.M., Egan C.L., Tangoren I.A., Li L.J., Laughinghouse K.A., Guzzo C.A. Generalized pustular dermatosis following paclitaxel therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36(7):559–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1997.tb01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnock T., Wang J., Suys E., De Coninck A., Roseeuw D. Vesiculopustular eruption associated with mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumopathy. Dermatology. 1996;192(1):73–74. doi: 10.1159/000246322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki R., Yamasaki M., Kawasaki Y., Nagasako R. Generalized pustular dermatosis caused by isoniazid. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112(4):504–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.