To the Editor:

The Veterans Health Administration (VA) is an integrated healthcare system whose mission is to provide high-quality care that meets veterans’ needs in a resource-conscious manner (1). When the VA cannot achieve predefined access standards, veterans are eligible for referral to non-VA providers (i.e., community care) under a fee-for-service reimbursement model. Historically, community care was managed via direct “Fee Basis” relationships between VA facilities and private providers. However, a fundamental shift in these relationships began with the Veterans Choice Program. In an attempt to streamline referrals, “Choice” used third-party administrators to contract with outside providers and coordinate care on the VA’s behalf (2). Over time, Choice referrals expanded and now comprise ∼10% of the VA’s budget, with annual costs exceeding $5 billion (3). Given these large investments, it is essential to understand the efficiency and value of community care.

The challenges of providing care for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are representative of those seen with many specialty services. Almost half of veterans are at high risk for OSA (4), and community sleep programs represent an opportunity to improve access to care. Traditionally, laboratory-based polysomnography was necessary to diagnose OSA, but portable home sleep apnea tests (home tests) provide an efficient patient-centered option. Home tests have equivalent accuracy among patients for which they are appropriate (5) and cost ∼74% less than polysomnography ($170 vs. $663 per test) (6). We compared relative polysomnography use among veterans tested by VA, Fee Basis, and Choice providers.

Methods

We obtained national VA administrative data for veterans’ first sleep studies performed during October 2014 to July 2016, a period of transition from Fee Basis to Choice for community care. This operational evaluation project was sponsored by the VA Office of Veterans Access to Care, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC. The activities were undertaken in support of a VA operational project and did not constitute research, in whole or in part, in compliance with VA Handbook 1058.05. Therefore, institutional review board approval was not required. We collected information regarding demographics, diagnoses, medications, and sleep studies performed within the VA and community care, using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to identify polysomnograms (CPT 95808, 95810, and 95811) or home tests (CPT 95800, 95801, and 95806). Because of divergent relationships with the VA, we chose a priori to stratify community care by Fee Basis and Choice. We excluded patients with home test contraindications, such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke, neuromuscular weakness, and chronic opioid use (5). We also present testing by region.

Because home tests are appropriate for patients with a moderate–high OSA risk (5), we recorded confounders that have been hypothesized to track with pretest OSA risk and medical complexity: body mass index, age, sex, race, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes, and Charlson Comorbidity Index in the year before testing (5, 7). We included distance from the nearest VA Medical Center (VAMC) to account for likelihood of community care referral. We performed logistic regression to account for potential confounding and performed multiple imputation to address the 8% missing body mass index values using 25 imputed datasets. We calculated adjusted ratios of home testing, with regression clustered by VAMC of service (VA), contracting VAMC (Fee Basis), or nearest VAMC (Choice). To contextualize resource use, we used Medicare reimbursement rates to estimate the average VA costs per 100 patients (6). Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp).

Results

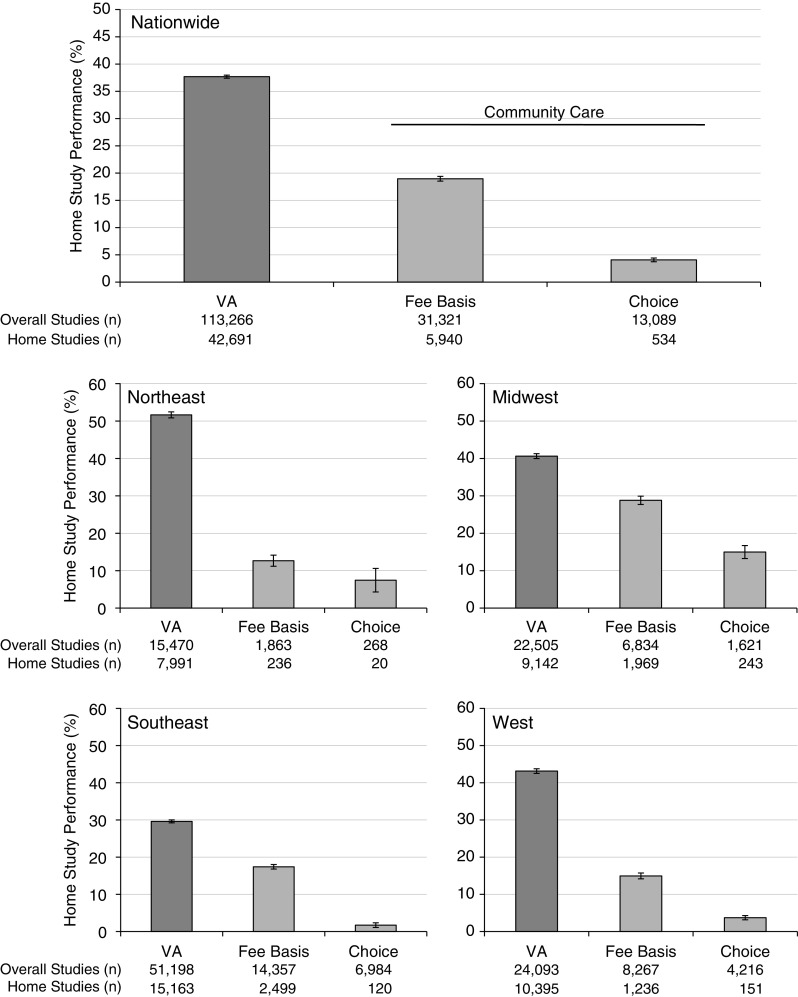

Among 203,371 patients undergoing sleep testing, we identified 157,676 (77.5%) without a home testing contraindication. Most of these patients had undergone VA studies (71.8%), followed by Fee Basis (19.9%) and Choice (8.3%). Regardless of where testing occurred, the patients had similar characteristics across age, demographics, and comorbidities (Table 1). VA providers performed 37.7% of studies as home tests, compared with 19.0% in Fee Basis and 4.1% in Choice (Figure 1). Because of lower home testing, every 100 veterans referred to Fee Basis represented $8,831 (95% confidence interval [CI], $8,587–9,076) greater costs than those treated by VA providers, and every 100 veterans referred to Choice represented $15,814 (95% CI, $15,603–16,024) greater costs than those treated by VA providers (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics and Sleep Study Use

| VA (n = 113,266) | Traditional Fee Basis (n = 31,321) | Choice (n = 13,089) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 51.5 (14.8) | 50.9 (14.6) | 51.5 (14.7) |

| Sex, M | 102,310 (90.3) | 28,490 (91.0) | 11,725 (89.6) |

| Race | |||

| White | 73,986 (65.3) | 21,023 (67.1) | 8,557 (65.4) |

| Black | 27,749 (24.5) | 6,158 (19.7) | 2,650 (20.3) |

| Native American | 840 (0.7) | 320 (1.0) | 151 (1.2) |

| Asian | 2,658 (2.4) | 1,001 (3.2) | 641 (4.9) |

| Multiracial and other | 8,033 (7.1) | 2,819 (9.0) | 1,090 (8.3) |

| Hispanic | 10,031 (8.9) | 3,804 (12.2) | 1,460 (11.2) |

| Distance from VA facility, km* | 34.4 (15.9–71.1) | 52.5 (19.6–110.7) | 51.8 (20.3–120.9) |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | 15,470 (13.7) | 1,863 (6.0) | 268 (2.1) |

| Midwest | 22,505 (19.9) | 6,834 (21.8) | 1,621 (12.4) |

| Southeast | 51,198 (45.2) | 14,357 (45.8) | 6,984 (53.4) |

| West | 24,093 (21.3) | 8,267 (26.4) | 4,216 (32.2) |

| Medical comorbidities and history | |||

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 32.8 (6.1) | 32.8 (6.2) | 32.9 (6.2) |

| Charlson score ≥2 | 18,958 (16.7) | 4,696 (15.0) | 2,154 (16.5) |

| Hypertension | 44,893 (44.1) | 13,236 (42.3) | 6,073 (46.4) |

| Diabetes | 23,178 (20.5) | 6,736 (21.5) | 2,841 (21.7) |

| Sleep study used | |||

| In-laboratory polysomnogram | 70,575 (62.3) | 25,381 (81.0) | 12,555 (95.9) |

| Home sleep apnea test | 42,691 (37.7) | 5,940 (19.0) | 534 (4.1) |

| Sleep study cost per 100 patients, $, mean (SD)† | 46,659 (23,028) | 55,491 (18,449) | 62,473 (9,486) |

Definition of abbreviation: VA = Veterans Health Administration.

Data are shown as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Data are shown as median (interquartile range) due to skewed distribution.

Average costs obtained from National 2016 Medicare Pricing Data for each sleep study Current Procedural Terminology code, including technical and professional fees.

Figure 1.

Use of home studies by Veterans Health Administration (VA), traditional Fee Basis, and Choice providers nationwide, stratified by region. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval of each proportion. Northeast refers to medical centers in Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs) 1–4; Midwest refers to VISNs 10, 11, 12, 15, and 23; Southeast refers to VISNs 5–9 and 16–17; and West refers to VISNs 18–22.

In adjusted models, both Fee Basis (adjusted risk ratio [aRR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.26–0.75) and Choice (aRR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.05–0.17) providers remained less likely to use home tests than VA providers. Compared with Fee Basis providers, Choice providers were less likely to use home tests (aRR, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.11–0.32). Despite regional variation in home testing, the overall pattern of reduced home testing in community care persisted (Figure 1).

Discussion

Home tests were performed in only a minority of patients, although there was a marked difference in the use of home tests between community care and the VA (5). Our results suggest that substantial cost savings could be achieved if the VA were to reduce its reliance on community care or encourage more efficient testing practices, particularly in certain regions. Community providers’ avoidance of home testing may relate to greater fee-for-service reimbursements for polysomnograms or to a number of other factors (8). For example, community providers may receive incomplete medical records, leading them to choose polysomnograms over home testing given the frequency of comorbidities (e.g., heart failure) in veterans (9). Community providers may also have less infrastructure to support home testing or be unaware of its equivalence in select populations (10).

Differences between Fee Basis and Choice suggest that care varies based on the nature of the VA’s arrangements with community providers. Direct Fee Basis relationships between VA facilities and community providers may reinforce communication and mutual knowledge of practice patterns. The Choice program, by contrast, was administered indirectly through third-party administrators, limiting contact between the VA and community providers (2). Our results have particular relevance given the planned expansion of patients’ eligibility for community care under the Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act (11). Our results suggest that the VA will need to focus on developing communication and coordination with community care providers during this expansion.

This study has some potential strengths and limitations. Our use of nationwide administrative data limits systemic bias and captures generalizable practice patterns of real-world practice. Although our approach did not ascertain symptoms that influence home test suitability (e.g., snoring) (5), we have no reason to believe the patients’ symptoms differed between groups. In addition, although numerous trials have suggested comparable outcomes with community care and home testing, we did not measure or compare patient outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence) (5). Finally, our average cost model likely underestimates the cost difference between community care and the VA. Although community care reimbursements are tied to Medicare rates (12), VA services typically cost less than Medicare (13). Additionally, our model did not incorporate added costs from community care clinic visits.

Our results suggest that there is a substantial opportunity to improve the value of sleep testing within the VA and raise concerns regarding the efficiency of community care. Our work suggests that as community care evolves under new appropriations, the VA should carefully build relationships and contract for services in a way that encourages patient-centered, value-based care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the VA Office of Rural Health and the VA Office of Veterans Access to Care, Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, through a MyVA Access Improvement Project Grant (VISN19 Denver Expanding Choice Provider Networks). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Data collection: J.A.T.-S. Data analysis: L.M.D. and S.S.C. Drafting of the manuscript: all authors.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201902-0313LE on June 17, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Department of Veterans Affairs FY 2018–2024 strategic plan [accessed 2018 Jul 1]Available from: https://www.va.gov/oei/docs/VA2018-2024strategicPlan.pdf

- 2. Sayre GG, Neely EL, Simons CE, Sulc CA, Au DH, Michael Ho P. Accessing care through the Veterans Choice Program: the veteran experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1714–1720. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnett PG, Hong JS, Carey E, Grunwald GK, Joynt Maddox K, Maddox TM. Comparison of accessibility, cost, and quality of elective coronary revascularization between Veterans Affairs and community care hospitals. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:133–141. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mustafa M, Erokwu N, Ebose I, Strohl K. Sleep problems and the risk for sleep disorders in an outpatient veteran population. Sleep Breath. 2005;9:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, Kuhlmann DC, Mehra R, Ramar K, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13:479–504. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Fee schedule. 2016. [accessed 2018 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/

- 7. Colaco B, Herold D, Johnson M, Roellinger D, Naessens JM, Morgenthaler TI. Analyses of the complexity of patients undergoing attended polysomnography in the era of home sleep apnea tests. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14:631–639. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pack AI. Dealing with a paradigm shift. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:925–929. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krishnamurthi N, Francis J, Fihn SD, Meyer CS, Whooley MA. Leading causes of cardiovascular hospitalization in 8.45 million US veterans. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mattocks KM, Mengeling M, Sadler A, Baldor R, Bastian L. The Veterans Choice Act: a qualitative examination of rapid policy implementation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care. 2017;55(Suppl 7)(Suppl 1):S71–S75. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legislation of 115th Congress . Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act 38 USC §1703B (2018) [accessed 2019 May 15]. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2372/text

- 12.Gidwani R, Hong J, Murrell S. Fee basis data. A guide for researchers. Menlo Park, CA: VA Palo Alto Health Economics Resource Center; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nugent GN, Hendricks A, Nugent L, Render ML. Value for taxpayers’ dollars: what VA care would cost at Medicare prices. Med Care Res Rev. 2004;61:495–508. doi: 10.1177/1077558704269795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.