Abstract

Governmental restrictions aspiring to slow down the spread of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks lead to impairments for economic operations, which impact transportation networks comprising the maritime, rail, air, and trucking industries. Witnessing a substantial increase in the number of infections in Germany, the authorities have imposed drastic restrictions on everyday life. Resulting panic buying and increasing home consumption had versatile impacts on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics in German food retail logistics. Due to the lack of prior research on the effects of COVID-19 on transport volume in retail logistics, as well as resulting implications, this article aspires to shed light on the phenomenon of changing volume and capacity dynamics in road haulage. After analyzing the transport volume of n = 15,715 routes in the timeframe of 23.03.2020 to 30.04.2020, a transport volume growth rate expressing the difference of real and expected transport volume was calculated. This ratio was then examined concerning the number of COVID-19 infections per day. The results of this study prove that the increasing freight volume for dry products in retail logistics does not depend on the duration of the COVID-19 epidemy but on the strength quantified through the total number of new infections per day. This causes a conflict of interest between transportation companies and food retail logistics for non-cooled transport capacity. The contributions of this paper are highly relevant to assess the impact of a possibly occurring second COVID-19 virus infection wave.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pandemic disease, Retail logistics, Transport volume, Freight capacity

Highlights

-

•

Examines the impact of COVID-19 on German food retail logistics.

-

•

Empirical analysis through transport volume data obtained from n=15.715 routes.

-

•

The results indicate that transport volume does not depend on the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic but on the individual strength.

-

•

Results summarized in a system dynamics framework are relevant for a possibly occurring second COVID-19 wave.

1. Introduction

Epidemic and pandemic outbreaks, such as the dengue fever, the swine influenza, the avian flu, and recently the COVID-19 virus, have a severe and versatile impact on the society, as well as the economy. Aspiring to slow down the spread of the highly contagious COVID-19 virus, governments around the world decided to impose several temporary restrictions. The restrictions include e.g., (1) contact restrictions and the distance rules, (2) temporary closure of trade and service companies, as well as, gastronomy, hotel business, and leisure facilities, (4) travel restrictions within a country and especially for non-essential travel, or (5) the obligation to wear a mouth-and-nose cover when using public transport. These measures have a significant impact on the global economy and, consequently, on the transportation of goods, passengers, as well as information. In today's increasingly globalized world, functioning supply chains are a major success factor for economic prosperity enabled by freight transportation. Pandemic outbreaks such as the COVID-19 virus are disruption risk factors for supply chains characterized by a very strong and immediate impact on the supply chain network design structure (Ivanov, 2020). Therefore, understanding the impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics is of central importance.

The impact of COVID-19 is an interdisciplinary discussed topic in social sciences. Research object on different levels of investigation are, but are not limited to, environmental developments (Saadat et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020), agriculture (Siche, 2020), travel behavior (de Vos, 2020), global supply chains (Ivanov, 2020), society and global environment (Chakraborty and Maity, 2020). Due to the lack of prior research on the impact of COVID-19 on transport volume in retail logistics, as well as resulting implications on freight capacity demand, this article aspires to answer the following research questions: (1) “What is the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and changing purchasing behavior on the transport volume growth in food retail logistics?” and (2) “What are resulting implications of freight capacity demand of retail logistics?”. The relevance of this question becomes prominent when looking at the severe and versatile consequences of COVID-19 on society and the economy. This article aims to shed light on the phenomenon of changing supply and demand dynamics in road haulage.

This paper is structured as follows: the literature review section highlights the relationship of epidemic outbreaks and interdisciplinary transportation research. Then, the Methodology section describes the design of the case analysis, the cross-correlation, and regression analysis, as well as the methodological approach of system dynamics for a deviation regarding transport volume and freight capacity demand. The empirical investigation uses route planning data from a German food retailing company. The results of the regression indicate that the number of new COVID-19 cases influences the increase in the transport volume growth of dry products. Implications on freight capacity demand are derived from the empirical findings by inductive reasoning and summarized in a system dynamics framework. Finally, conclusions and an outlook on future research directions are presented.

2. Epidemic outbreaks and transportation research

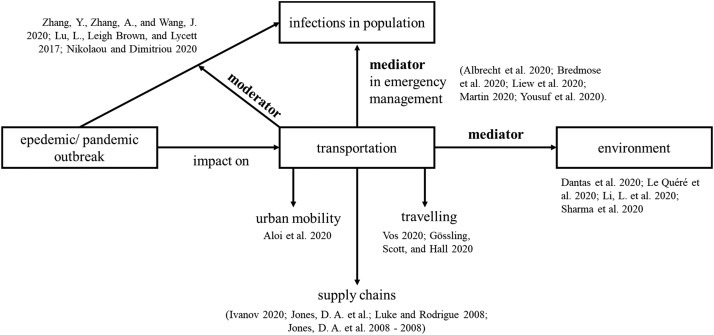

Maritime, rail, air, and road transport can play different roles before, during, and after different stages of epidemic outbreaks. According to the World Health Organization, these stages can be separated in (1) introduction, and emergence phase, (2) localized transmission phase, (3) amplification phase, and (4) reduced transmission phase (World Health Organization, 2018). The following literature framework illustrates the different functions of transportation as a dependent, mediating, and moderating variable.

2.1. Transportation as a mediator before and during epidemic outbreaks

If the connection between variables A and B is mediated by a third variable, this variable is called the mediator variable. It is located in the middle of the causal chain. As epidemic and pandemic outbreaks cause severe disruptions in industrial operations or infrastructure, reduced transport volume leads to a significant reduction of traffic. This reduction has an impact on the environment and is especially discussed in the context of COVID-19 and its versatile governmental restrictions during lockdown periods (Dantas et al., 2020; Le Quéré et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2020). On the other hand, epidemic outbreaks lead to life-threatening infections of people, which requires adequate emergence management. To lower the negative impact of diseases on the population, fast road- and air-based patient transport is discussed (Albrecht et al., 2020; Bredmose et al., 2020; Liew et al., 2020; Martin, 2020; Yousuf et al., 2020).

2.2. Transportation as a moderator during epidemic outbreaks

The moderator effect is a multiplicative one. The extent of the relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable depends on the characteristics of the moderator variable. Therein, public transport is often examined as a reinforcing factor for spatial diffusion, making epidemic outbreaks to pandemics (Zhang et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2017; Nikolaou and Dimitriou, 2020) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Theoretical framework for epidemic outbreaks and transportation research.

2.3. Epidemic outbreaks and the impact on transportation

Epidemic outbreaks and governmental restrictions aspiring to slow down the spread of these outbreaks lead to impairments for economical operation, which impacts transportation networks comprising the maritime, rail, air, and trucking industries. This is examined regarding travel behavior and the impact on the aviation industry by Gössling et al. (2020) and de Vos (2020). Furthermore, Aloi et al. (2020) investigate the impact of COVID-19 on urban mobility, stating that overall mobility fall of 76%, especially driven by the public transport users that dropped by up to 93%. Finally, trade restrictions, demand restraint, and lack of skilled labor significantly impact supply chains and consequently freight volume (Jones et al., 2008; Luke and Rodrigue, 2008). A simulation of the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains and in the context of COVID-19 is presented by Ivanov (2020).

3. Methodology

The case study is developed in two depots of a large German full range food retailing company, which are responsible for the complete and on-time delivery of 820 supermarket stores. The transport volume comprises all orders placed by the grocery shops including five assortment groups: (1) dry products containing, e.g., alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, hygiene products, washing and cleaning materials, or pet food, (2) frozen products, (3) fresh and perishable fruits and vegetables, (4) dairy products, and (5) raw fish and meat. The expected transport volume per assortment and week is forecasted when planning the total budget of the transport unit. Therefore, each depot has an expected transport volume per day. Aspiring to estimate the impact of COVID-19 on transport volume, the real transport volume per assortment is of particular interest. Therefore, data regarding the transport volume was obtained through the companies route planning software by analyzing n = 15,715 routes in the timeframe of 23.03.2020 to 30.04.2020. For a more in-depth analysis of the COVID-19 impact, a dataset from the European Union Open Data Portal (2020) was used. The dataset contains the number of cases and deaths per day from 31.12.2019 to 30.04.2020, including 208 countries around the world.

To quantify the impact of COVID-19, the two datasets were analyzed by applying correlation, as well as linear regression analyses. It is the method of choice in this study as it investigates how a dependent metric variable can be described by one or more independent metric variables through a linear equation. Since the goal of this study is to investigate the relationship between cause (COVID-19 outbreak) and effect (freight market dynamics), regression analysis quantifies the sequence of events and examines whether they are related to each other. Therein, the transport volume growth per assortment group was used as a dependent variable. The transport volume growth is expected to be influenced by COVID-19, which is operationalized by the number of cases and the number of deaths per day. The final dataset consists of the following indicators: (1) date of observation, (2) new cases per day, (3) cumulated number of cases, (4) new deaths per day, (5) cumulated number of deaths, as well as, transport volume growth as a percentual difference of planned and real transport volume for (6) dry products, (7) frozen products, (8) fresh and perishable fruits and vegetables, (9) dairy products, and (10) raw fish and meat.

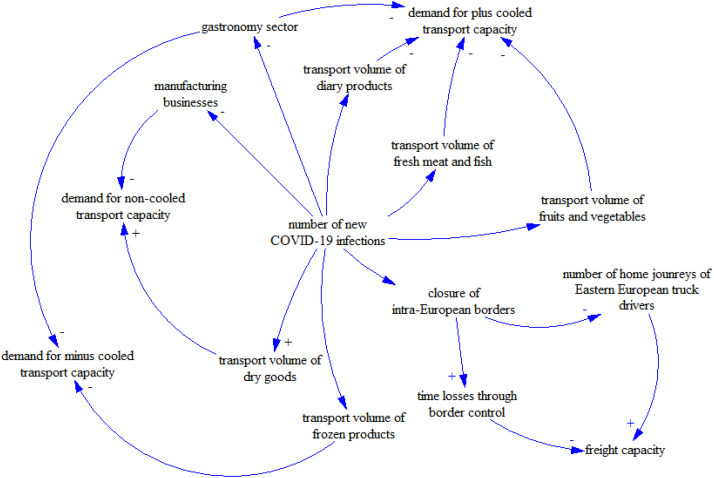

After the regression analysis, the interdependencies of COVID-19 and transport logistics in retail logistics are summarized in a system dynamics framework. The system dynamics methodology, developed by Jay W. Forrester in the 1950s as industrial dynamics, initially aimed to solve problems of top management (Forrester, 1961). It includes “[…] a perspective and set of conceptual tools that enable us to understand the structure and dynamics of complex systems” (Sterman, 2000, p. VII). As management problems contain various elements in several systems and sub-systems interacting with each other, system dynamics abstracts these elements, takes an aggregated view, and captures the dynamic behavior of a system over time by mathematical modeling and visualizing. Causal loop diagrams have been applied to shed light on the interplay and resulting mechanisms of various variables and levels in complex systems through visualizing a reference model (Sterman, 2000). The variables are connected with influence lines forming causal chains and indicating if the effected variable is influenced positively (sign “+”) or negatively (sign “−”).

4. Results of empirical analysis

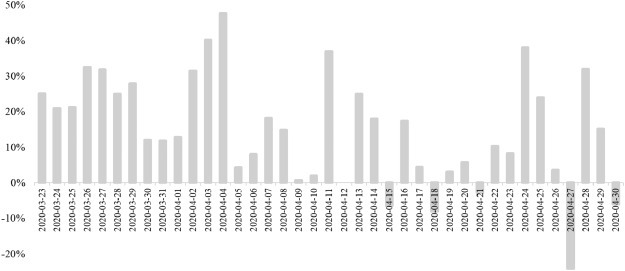

Aspiring to answer the formulated research question “What is the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and changing purchasing behavior on the transport volume in food retail logistics?” a cross-correlation analysis was conducted by using the PerformanceAnalytics package in R. As an explorative statistic analysis, the application of a correlation matrix sheds light on the interconnections of all available variables. To provide deeper insights regarding the development of the total transport volume, Fig. 2 illustrates the total transport volume compared to the expected transport volume in percentage and per day.

Fig. 2.

Development of the total transport volume in the examined time period.

Table 1 summarises the results of a cross-correlation matrix for the indicators (2) to (10).

Table 1.

Correlation matrix for independent (2–5) and dependent(6–10) transport volume variables.

| (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of new cases (2) | 1.00 | −0.70 | −0.21 | −0.80 | 0.77 | 0.38 | −0.08 | −0.34 | −0.15 |

| Cumulated cases (3) | 1.00 | 0.68 | 0.95 | −0.70 | −0.73 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.25 | |

| Number of new deaths (4) | 1.00 | 0.54 | −0.45 | −0.55 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.02 | ||

| Cumulated deaths (5) | 1.00 | −0.73 | −0.65 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 0.32 | |||

| Dry products (6) | 1.00 | 0.52 | −0.03 | −0.22 | −0.20 | ||||

| Frozen products (7) | 1.00 | −0.15 | −0.19 | −0.27 | |||||

| Fruits and vegetables (8) | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.36 | ||||||

| Dairy products (9) | 1.00 | 0.28 | |||||||

| Fish and meat (10) | 1.00 |

The results indicate that the highest correlation between transport volume measures and COVID-19 measured are within the categories of new COVID-19 cases per day and new deaths per day. A highly significant correlation can be stated for the linear statistical relationship of new cases per day and transport volume of dry products indicated through a correlation coefficient r = 0.77.

For a more in-depth analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on individual assortment groups, the linear statistical relationship between the number of new COVID-19 cases and the percentual difference of planned and real transport volume for (6) dry products, (7) frozen products, (8) fruits and vegetables, (9) dairy products, and (10) raw fish and meat was analyzed in a further regression analysis. The results are summarized in the Table 2 .

Table 2.

Results of linear regression analysis for transport volume growth and new COVID-19 cases.

| Dependent variables: transport volume growth per assortment group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry products | Frozen products | Fruits and vegetables | Dairy products | Raw fish and meat | |

| New COVID-19 cases | −0.193⁎⁎⁎ | −0.073 | −0.043 | 0.641⁎⁎⁎ | 0.201⁎ |

| (0.061) | (0.051) | (0.071) | (0.204) | (0.115) | |

| Observations | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| R2 | 0.592 | 0.145 | 0.007 | 0.118 | 0.024 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.581 | 0.122 | −0.020 | 0.094 | −0.003 |

| Residual std. error (df = 37) | 0.157 | 0.130 | 0.183 | 0.525 | 0.296 |

| f statistic (df = 1; 37) | 53.748⁎⁎⁎ | 6.263⁎⁎ | 0.257 | 4.944⁎⁎ | 0.893 |

p < 0.01.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.01.

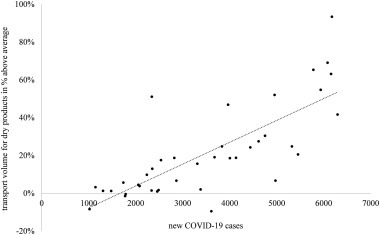

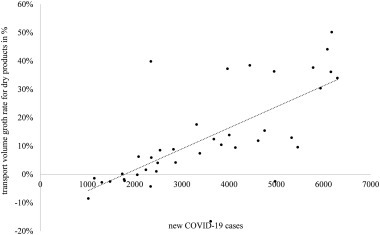

The coefficient of determination, denoted as R2, indicated the proportion of the variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variable. A R2 value of 0.592, as well as an adjusted R of 0.581 proves that the number of new COVID-19 cases has a significant impact on the increase of total transport volume for dry products for the examined depots. On the other hand, the volume of all other product groups is independent form the new COVID-19 cases. The Fig. 3 illustrates the linear statistical relationship of new COVID-19 cases and the percentual difference of planned and real transport volume for dry products (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 3.

Results of regression analysis for new COVID-19 cases and transport volume of dry products.

Fig. 4.

Results of regression analysis for new COVID-19 cases and transport volume growth rate.

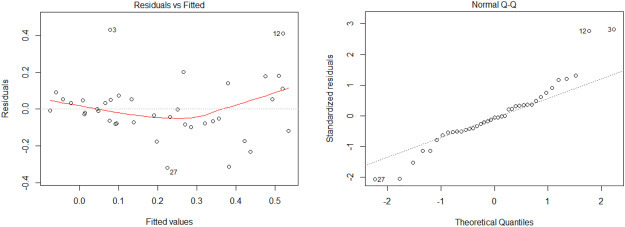

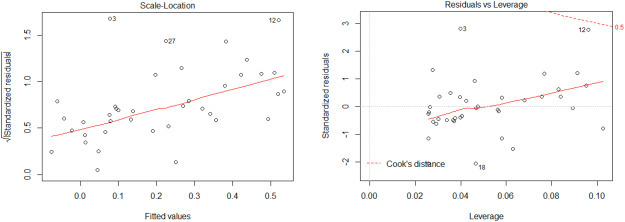

Aiming to ensure that the data is suitable for further investigation, several statistical tests were conducted, including (a) residuals versus fitted plot, (b) normal Q-Q, (c) scale location, and (d) residuals versus leverage. When conducting a residual analysis, a “residuals versus fits plot” is the most frequently created plot. It is a scatter plot of residuals on the y-axis and fitted values (estimated responses) on the x-axis. The plot is used to detect non-linearity, unequal error variances, and outliers. For (a), it can be determined that the residuals bounce randomly around the 0-line. Therefore, it can be suggested that the assumption of a linear relationship is reasonable. None residual stands out from the basic random pattern of residuals, which indicates that there are no outliers. A Normal Q–Q plot is used to compare the shapes of distributions, providing a graphical view of how properties such as location, scale, and skewness are similar or different in the two distributions. Q–Q plots can be used to compare collections of data or theoretical distributions. Concerning (b), the points form a roughly straight line, indicating a normal distribution (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Residuals versus fitted and normal Q-Q for linear regression analysis.

The Scale-Location plot shows whether the residuals are spread equally along with the predictor range, e.g., homoscedastic. On optimum is achieved when the line on this plot is horizontal with randomly scattered points on the plot. The Residuals versus Leverage plots help to identify critical data points on the model. The points the analysis is searching for are values in the upper right, or lower right corners, which are outside the red dashed Cook's distance line. These are points that would be influential in the model, and removing them would likely noticeably alter the regression results.

5. Discussion

The regression analysis conducted in the previous chapter illustrates a strong linear statistical relationship of dry product transport volume growth and the number of new COVID-19 cases in Germany. Therefore, it can be derived that changing purchasing behavior impacts non-cooled assortment groups and is mostly dependent on the individual daily situation. The interesting point for transportation managers is that food demand in Germany does not depend on the duration of epidemics and pandemics crisis but on the recent strength. In periods with a high number of new COVID-19 cases, transport capacity demand will rise within the food retailing sector. It is critical to mention that this only applies to non-cooled transport capacity. On the other hand, plus cooled or minus cooled transport capacity is hardly influenced as the demand for these product assortments is independent of the COVID-19 outbreaks. On the other hand, sectors like gastronomy or the manufacturing business had to shut down a majority of their operations due to the contact spear for all German citizens introduce on 23.03.2020 by the German government. Thus, a large number of non-cooled transport capacity from the manufacturing business, as well as plus cooled transport capacity from the gastronomy sector, is available on the freight market.

Aspiring to slow down the spread of COVID-19, most member states of the European Union (EU) closed their internal borders, leading to a lockdown for personnel transportation and a slowdown of freight transport in the Schengen area. As EU countries can introduce border checks at their internal borders for a limited period if there is a serious threat to public policy or internal security, waiting times at checkpoints caused time delays for cross-border freight transportation. On the other hand, quarantine obligations lead to the high availability of human workforce in freight transportation, more precise, professional truck drivers within the EU member states. While French, Dutch, and German freight forwarders employ a high proportion of professional truck drivers originating from Eastern Europe, entry requirements, e.g., from Poland and Romania, reduced the level of homeward journeys. As the drivers wanted to avoid the 14-day quarantine in their home countries, holidays were postponed, which in turn had a positive effect on the availability of driving personnel and consequently on freight capacity in Western European countries. Fig. 6 illustrates the system dynamics framework for the impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and demand (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 6.

Scale-location and residual versus leverage for linear regression analysis.

Fig. 7.

System dynamics framework for the impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and demand.

The outlined situation leads to a conflict of interest between transportation companies and food retail logistics. While the latter have to face short-term and individual dry product transport volume peaks, the transportation companies are confronted with uncertainty regarding future commissions in the manufacturing sector. On the other hand, plus cooled transport capacity is significantly higher than the demand. As retail logistics delivers the expected transport volume independent from the number of COVID-19 infections, the demand originated from the gastronomy sector collapsed due to the national shut-down.

6. Conclusion

The paper has shown a way forward in analyzing the impact of COVID-19 and the resulting change in the individual purchasing behavior, caused by panic buying and increasing home consumption. This was done by investigating the transport volume growth and freight capacity demand through an empirical analysis in German food retail logistics based on transport volume planning and real transport volume in the timeframe of 23.03.2020 to 30.04.2020. The contribution of this paper consists of (1) the quantification of consumer behavior during COVID-19, and (2) a deeper understanding of transport volume and transport capacity dynamics in non-cooled, plus cooled and minus cooled transportation sector. Of special value for further management, improvements are the outlined conflicts of interest between long-term and short-term agreements for transport companies and retail, logistic managers. Limitations of this research include the real-life data restrictions due to limited access to transport volume for different countries. Therefore, all results address a specific location and time combination and are primarily not transferable. Further research avenues can be directed at elaborating simulation approaches of transport volume and capacity dynamics for a possibly occurring second wave of COVID-19 infections. Furthermore, researching the impact on other branches, as well as in third world countries, is of central importance.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dominic Loske:Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for the valuable comments, making it possible to improve the quality of this paper.

References

- Albrecht Roland, Knapp Jürgen, Theiler Lorenz, Eder Marcus, Pietsch Urs. Transport of COVID-19 and other highly contagious patients by helicopter and fixed-wing air ambulance: a narrative review and experience of the Swiss air rescue Rega. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2020;28(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00734-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloi Alfredo, Alonso Borja, Benavente Juan, Cordera Rubén, Echániz Eneko, González Felipe, Ladisa Claudio, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on urban mobility: empirical evidence from the City of Santander (Spain) Sustainability. 2020;12(9):3870. doi: 10.3390/su12093870. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bredmose Per P., Diczbalis Monica, Butterfield Emma, Habig Karel, Pearce Andrew, Osbakk Svein Are, Voipio Ville, Rudolph Marcus, Maddock Alistair, O'Neill John. Decision support tool and suggestions for the development of guidelines for the helicopter transport of patients with COVID-19. Scand. J. Trauma Resusc. Emerg. Med. 2020;28(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s13049-020-00736-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty Indranil, Maity Prasenjit. COVID-19 outbreak: migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138882. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas Guilherme, Siciliano Bruno, França Bruno Boscaro, da Silva Cleyton M., Arbilla Graciela. The impact of COVID-19 partial lockdown on the air quality of the City of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;729:139085. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Union Open Data Portal COVID-19 Coronavirus data. 2020. https://data.europa.eu/euodp/en/data/dataset/covid-19-coronavirus-data

- Forrester J.W. MIT Press; 1961. Industrial Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling Stefan, Scott Daniel, Michael Hall C. Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020:1–20. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov Dmitry. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: a simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Transp. Res. E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020;136:101922. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Dean A., Nozick Linda K., Turnquist Mark A., Sawaya William J. Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS 2008) IEEE; 2008. Pandemic influenza, worker absenteeism and impacts on freight transportation; pp. 1530–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Le Quéré Corinne, Jackson Robert B., Jones Matthew W., Smith Adam J.P., Abernethy Sam, Andrew Robbie M., De-Gol Anthony J., et al. Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Li, Li Qing, Huang Ling, Wang Qian, Zhu Ansheng, Xu Jian, Liu Ziyi, et al. Air quality changes during the COVID-19 lockdown over the Yangtze River Delta Region: an insight into the impact of human activity pattern changes on air pollution variation. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;732:139282. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew Mei Fong, Siow Wen Ting, Yau Ying Wei, See Kay Choong. Safe patient transport for COVID-19. Crit. Care (Lond. Engl.) 2020;24(1):94. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2828-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Lu, Leigh Brown Andrew J., Lycett Samantha J. Quantifying predictors for the spatial diffusion of avian influenza virus in China. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017;17(1):16. doi: 10.1186/s12862-016-0845-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke Thomas C., Rodrigue Jean-Paul. Protecting public health and global freight transportation systems during an influenza pandemic. Am. J. Disaster Med. 2008;3(2):99–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Terry. Fixed wing patient air transport during the Covid-19 pandemic. Air Med. J. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amj.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou Paraskevas, Dimitriou Loukas. Identification of critical airports for controlling global infectious disease outbreaks: stress-tests focusing in Europe. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020;85:101819. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2020.101819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat Saeida, Rawtani Deepak, Hussain Chaudhery Mustansar. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138870. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Shubham, Zhang Mengyuan, Anshika Jingsi Gao, Zhang Hongliang, Kota Sri Harsha. Effect of restricted emissions during COVID-19 on air quality in India. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138878. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siche Raúl. What is the impact of COVID-19 disease on agriculture? Sci. Agropecu. 2020;11(1):3–6. doi: 10.17268/sci.agropecu.2020.01.00. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sterman J.D. Irwin/McGraw-Hill; Boston: 2000. Business Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World. [Google Scholar]

- de Vos Jonas. The effect of COVID-19 and subsequent social distancing on travel behavior. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;5:100121. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2018. Managing Epidemics: Key Facts About Major Deadly Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf Beena, Sujatha Kandela Swancy, Alfoudri Huda, Mansurov Vladisalav. Transport of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06115-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Yahua, Zhang Anming, Wang Jiaoe. Exploring the roles of high-speed train, air and coach services in the spread of COVID-19 in China. Transp. Policy. 2020;94:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]