Abstract

There are 46 Aloe species identified from Ethiopia out of which 67.3% are endemics but comprehensive data on their ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural values are lacking. Interview, focus group discussion (FGD), and guided field walks were conducted with 210 respondents (152 men and 58 women). Relative frequency of citation (RFCs), informants' consensus factor (Fic), use value (UVs), relative importance index (RIs), and cultural value index (CV) were analyzed. Non-parametric Kruskal Wallis and Wilcoxon tests were performed using R software. Twenty-three Aloe species were recorded in the study areas with 196 use-reports and 2158 citations, grouped into six major use categories (NUC = 6). Medicinal use categories accounted for 149 use-reports (76%) with 1607 citations. The species with the highest numbers of use-reports were Aloe megalacantha subsp. alticola, A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora and A. calidophila of which 87, 75 and 61.1% respectively were medicinal uses. Aloe calidophila has highest values in all indices UV (11.72), RFC (0.68), RI (0.89), and CV (6.2). Among Aloe parts, leaf exudate accounted for 111 use-reports (49.1%) of which 92.9% were used for medicinal purposes. Aloe retrospiciens and A. ruspoliana were reported poisonous to carnivores. Fic values of the six major use categories ranged from 0.86 to 0.22. Elderly people (>60) had more knowledge than 25–40 and 41–60 age groups (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 12.17, df = 3, p = 0.006), which is significant difference in depth of ethno-medicinal knowledge. Men had more knowledge of medicinal uses than women (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.002) significantly different, while women were knowledgeable than men for cultural uses like, cosmetic (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.06), not significantly different. The ways in which aloes are used and valued have implications for their future medicinal utility, which instigate detailed phytochemical and pharmacological studies.

Keywords: Aloe calidophila, Aloe exudate, Aloe gel, Aloe retrospiciens, Ethnomedicine, Environmental science, Veterinary medicine, Health sciences, Pharmaceutical science

Aloe calidophila; Aloe exudate; Aloe gel; Aloe retrospiciens, Ethnomedicine, Environmental science; Veterinary medicine; Health sciences, Pharmaceutical science

1. Introduction

The genus Aloe L. belongs to family Asphodelaceae [1], which has 560 accepted species and 21 infraspecific taxa [2] is renowned for its use in herbal medicine throughout its native range in Africa South of the Sahara, the Arabian Peninsula, Madagascar and the Mascarene Islands [3]. The dried latex extracted from the leaves has been used medicinally in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East for hundreds of years [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Aloes has been used for the treatment of wounds and skin complaints, malaria, microbial infections, and complaints of the digestive system [9, 10, 11, 12, 13]. In addition, commercial preparations containing Aloe species include laxative drugs, health drinks and tonics, after shaving gel, mouthwash and toothpaste, hair tonic and shampoo, and skin-moistening gel [14, 15, 16].

Ethiopia, a likely centre of diversity for Aloe, has 46 identified and documented species with three subspecies, of which 67.3% are endemic. Several of these are highly threatened [17, 18]. Three local centres of endemism are recognised in Ethiopia, each with characteristic endemic species (Table 1) [18,19]. Six species of Aloe in Ethiopia were classified on the IUCN Red List [20] as endangered (A. harlana and A. yavellana), near threatened (A. tewoldei and A. pubescens), and vulnerable (A. retrospiciens and A. rugosifolia), while many of the remaining species are still data-deficient [21, 22, 23, 24]. Despite conservation concerns, aloes have been recognised for their economic potential in Ethiopia [19], particularly for livelihood security, economic development and enhancing biodiversity conservation on marginal lands [25]. For example, Aloe debrana leaf mesophyll is used in a thickening agent [26] and for treating sisal fibre for packing Ethiopian export coffee (e.g. www.gseventiplc.com). In the Borena of Oromia region in Southeast Ethiopia, the local community has been cultivating A. calidophila to collect aloe leaf exudate and gel for small-scale aloe-soap manufacturing [27]. Data collated from the literature indicated that the medicinal uses of the genus Aloe comprised 74% of the use records [28] in which the use of exudate was common.

Table 1.

The three local centres of Aloe endemism recognised in Ethiopia.

| Center of endemism | Floristic regions | Number of endemic species | List of endemic species and infraspecific taxa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern and central highlands, north and west of the great rift valley | SU, KF, IL, WG, GJ, GD, WU, TU | 15 | Aloe adigratana, A. ankoberensis, A. benishangulana, A. camperi, A. clarkei, A. debrana, A. elegans, A. monticola, A. percrassa, A. pulcherrima, A. schelpei, A. sinana, A. steudneri, A. trigonantha, and A. weloensis |

| Eastern highlands and lowlands | AF, HA | 7 | Aloe bertemariae, A. harlana, A. mcloughlinii, A. megalacantha subsp. alticola, A. pirottae; A. pubescens; and A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora |

| Southern highlands, lowlands and rift valley | AR, BA, SD, GG | 11 | Aloe elkerriana, A. friisii, A. ghibensis, A. gilbertii subsp. gilbertii, A. gilbertii subsp. megalacanthoides, A. jacksonii, A. kefaensis, A. otallensis, A. tewoldei, A. welmelensis, and A. yavellana |

SU = Shew; KF = Kefa; IL = Ilubabur; WG = Welega; GJ = Gojam; GD = Gonder; WU = Welo; TU = Tigray; AF = Afar; HA = Harargae; AR = Arsi; BA = Bale; SD = Sidamo; GG = Gamo Gofa.

Despite the limited reports on the uses and conservation concerns for aloes of Ethiopia, their ethnomedicinal and biocultural values, and the impact of these values on sustainable use have not previously been assessed systematically. It is expected that people will be motivated to conserve resources that are most important to them, in contrast to resources perceived as less useful [29, 30, 31]. In this regard, further effort to improve the perception of local community towards the resource is needed. This can be achieved by indicating the invisible but potential values of the genus Aloe for effective conservation of the genus Aloe. In addition, it has been hypothesized that the local communities in all the study areas make use of Aloe species arbitrarily for similar purpose and irrespective of different cultural/ethinic communities on the use of Aloe species. Therefore, we comprehensively investigated ethnomedicinal values, biocultural importance, and the emic perception of the wild population status of Aloe species in the East and South of the Great Rift Valley floristic region of Ethiopia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study areas

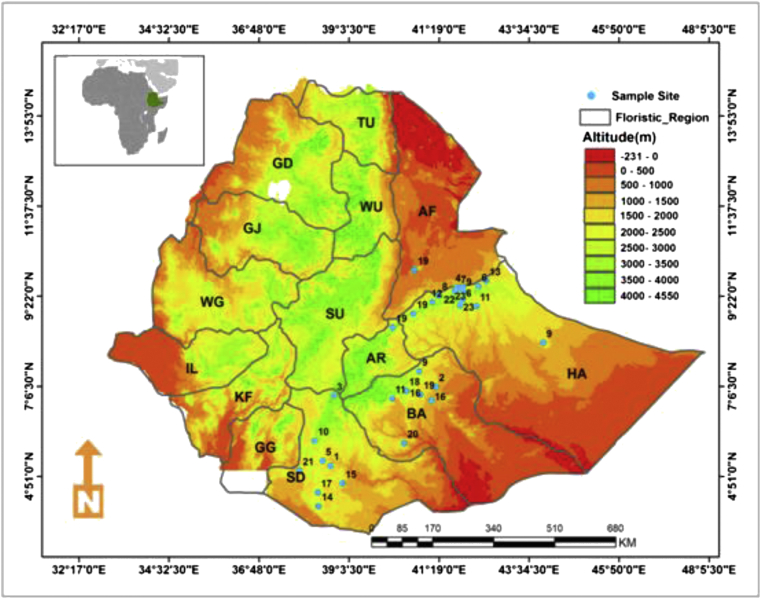

This study focused on the eastern, southeastern, and southern floristic regions of Ethiopia called Hararge (HA), Bale (BA), Sidamo (SD), Arsi (AR), and Afar (AF) floristic regions, which are stated as east and south of the Great Rift Valley floristic regions in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The study areas, stated as east and south of the Great Rift Valley floristic regions in this study (Site numbers indicated Aloe species: 1 = A. calidophila; 2 = A. citrina; 3 = A. gilbertii subsp. gilbertii; 4 = A. harlana; 5 = A. lateritia; 6 = A. macrocarpa; 7 = A. mcloughlinii; 8 = A. megalacantha subsp. alticola; 9 = A. megalacantha subsp. megalacantha; 10 = A. otallensis; 11 = A. pirottae; 12 = A. pubescens; 13 = A. retrospiciens; 14 = A. rivae; 15 = A. rugosifolia; 16 = A. ruspoliana; 17 = A. secundiflora; 18 = A. tewoldei; 19 = A. trichsantha subsp. longiflora; 20 = A. welmelensis; 21 = A. yavellana; 22 = AHU51; 23 = AHU53).

2.2. Data collection

Comprehensive data was collected on the ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural values, population trends of species in the natural habitat from the emic perspective, and associated indigenous knowledge of Aloe species in these floristic regions. Data was collected in the different seasons from 2017 (March to April and October to November) to 2018 (January to February and June to July). A total of 210 respondents (152 men and 58 women) from four cultural communities (Oromo, Somali, Afar, and Harari) participated. Informants were either randomly chosen (RI) or were systematically selected traditional healers (TH/key informants) who have in-depth traditional knowledge concerning multi-utility of Aloe species of their locality. Age, gender, and occupation (Table 2) were considered, as suggested by Martin [32] and Caruso et al, [33].

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of informants representing ethnic communities in east and south of the Great Rift Valley Floristic regions, Ethiopia.

| Total Informant | Oromo (N = 140) | Somali (N = 32) | Afar (N = 24) | Harari (N = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 97 (69.3%) | 25 (78.1%) | 19 (79.2%) | 11 (78.6%) |

| Women | 43 (30.7%) | 7 (21.9%) | 5 (20.8%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| RI | ||||

| Men | 60 | 16 | 14 | 8 |

| Women | 33 | 5 |

4 | 2 |

| TH/key informants | ||||

| Men | 37 | 9 | 5 | 3 |

| Women | 10 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Age categories∗ | ||||

| 25–40 | 50 (32.8 ± 5.3) | 9 (31.1 ± 5.5) | 4 (30.3 ± 4.0) | 4 (32.6 ± 4.1) |

| 41–60 | 65 (51.7 ± 5.8) | 20 (50.3 ± 6.8) | 15 (51.9 ± 5.9) | 8 (51.1 ± 6.0) |

| above 60 | 25 (70.1 ± 6.4) | 3 (76.0 ± 5.7) | 5 (74.5 ± 6.6) | 2 (72.0 ± 5.2) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Farmers | 104 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Agro-pastoralist | 12 | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Pastoralist | 18 | 26 | 22 | 0 |

| Others | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 |

Number of informants = N (mean age ±standard deviation) for each age categories; RI = random informants, TH = traditional healers.

Ethnobotanical data collection procedures were approved by ethical committee for human involvement and use of lab animals in school of animal and range sciences of Haramaya University. Semi-structured interviews, focus group discussion (FGD), practical observation sessions, and guided field walk in Aloe localities were conducted after Oral Prior Informed Consent (PIC) was sought from every respondent. Most interviews were conducted in the field in order to avoid the risk of confusing identity of Aloe species. By repeated inquiries at least two times with the same informants the validity and reliability of recorded information was confirmed [32, 33, 34]. The respondents were asked to freely list all possible uses of each Aloe species, each time a plant was mentioned as “used” was considered as one “use-report”, and repeated mention of same use-report by different informants was taken as "use mention or number of citation". Data recorded were: vernacular names of Aloe species, local uses, parts used, ingredients added during the use formulations (if any), and locally marketable aloe products produced. For medicinal use-reports, the ailments treated, preparation procedures, method of administration, and antidote (if any) were recorded. In addition, population trends (noticeably increasing, increasing, noticeably decreasing, decreasing, stable, and not sure/uncertain) from emic perspective were recorded (Appendix II). However, vague use-reports, from which it was difficult to distinguish the specific values were avoided, e.g. “used for livestock disease treatment”; “it has cultural importance”; etc. Finally, the use-reports recorded were categorized into major use categories (UC) of level 1 and sub-categories of level 2 using the Economic Botany Data Standard [35].

Aloe specimens were identified using taxonomic keys in the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea [17], through visual comparisons with authenticated plant specimens kept at the National Herbarium (ETH) of Addis Ababa University and at Herbarium of Haramaya University, and authenticated by Prof. Sebsebe Demissew (Professor of Plant Systematics and Biodiversity). Voucher specimens of all species with all herbarium sheet data were deposited at both herbaria. Voucher numbers of Haramaya University were used in this study.

2.3. Data analysis

The data were organized and cleaned in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft office 2016), to be suitable for both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Qualitative data were analyzed following [32, 34, 36] like, free listing, part used, use-reports and use mentions. Quantitative data were analyzed using the corresponding formulas as follows:

2.3.1. Frequency of citation for use-report (FCUR)

Frequency of citation for use-report (FCUR) is the percentage of informants who mentioned each use-report of particular Aloe species, which has been calculated using the formula:

| (1) |

where ni is the number of informants who cites each use-report per species and N is total number of informants.

2.3.2. Relative frequency of citation (RFCs)

Relative frequency of citation was calculated by dividing the frequency of citation (FC) of a species by total number of informants (N) involved in the five floristic regions that makes N to varies or the summation of use-report (∑URi) of all the informants interviewed for a species divided by N [37].

| (2) |

2.3.3. Informant consensus factor (Fic)

The informant consensus factor (Fic) of each Aloe species is the proportion of informants who independently reported its use against a particular use category calculated using the formula [38, 39]:

| (3) |

where, 'nur' is the “number of use-reports” in each use category and 'nt' is the “number of taxa used”.

2.3.4. Use value (UV)

Use value was used to demonstrate the relative importance of each Aloe species known locally, which can be calculated according to Albuquerque et al. formula [40]:

| (4) |

where, UVs refers to the use value of Aloe species 's', Ui to the number of different uses mentioned by each informant i per specific Aloe species, and N is the total number of informants interviewed for Aloe species 's'.

2.3.5. Relative importance index (RI)

This index takes into account the number of major use-categories only and calculated as follows [37]:

| (5) |

where, RFCs(max) is the relative frequency of citation over the maximum. It is obtained by dividing FCs by the maximum value in all Aloe species of the study [RFCs(max) = FCs/max (FC)], and RNUs(max) is the relative number of use-categories over the maximum, obtained dividing the number of uses of the species NUs = u = uNC u = u1 ∑ URu by the maximum value in all Aloe species of the survey RNs(max) = NUs/max (NU).

2.3.6. Cultural value index (CV)

This index estimates the cultural significance of each Aloe species, which combines the three variables, informant (i), a species (s), and use-category (u), which is calculated using the following formula [41]:

| (6) |

The first factor is the relationship between the numbers of different uses reported for ethnospecies (each Aloe species) and total number of use-categories. The second factor is the relative frequency of citation of a species. The third factor is the sum of all the UR for a species, i.e., the sum of number of participants who mentioned each use of a species, divided by N.

To test if there was any correlation between age of the informant and their knowledge on use of aloes (number of use-reports), the nonparametric Kruskal Wallis Test was performed. If there was a significant difference between the informant's gender and knowledge about use of aloes, the non-parametric pair wise Wilcoxon test was performed using R software version 3.3.4. for Windows using multicompview and R companion packages. P-values of less than 0.05 were taken as statistically significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural values of aloes with frequency of citation

A total of 23 Aloe species (Appendix I) were recorded in the study areas, of which 21 are found in the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea [17] and two (recorded as unknown, voucher number AHU51 and AHU53) could not be identified to species level. Among the Aloe species reported in this study, 11 species (52%) are endemic and near endemic. The total number of use-reports was 196, were categorized into six major use categories (NUC = 6) with 2158 citations (use mentions) from the 23 Aloe species (Table 3) by 210 respondents (Table 1). The major use categories (UC) are medicines (Md), social uses (SU), materials (Mt), environmental uses (EU), vertebrate poisons (VP), and food (Fd). The medicinal use category accounted 149 use-reports (76%) with 1607 citations. The highest number of use-reports was recorded for Aloe megalacantha subsp. alticola with 23 use-reports, of which about 87 % were medicinal uses for humans and livestock. The next most frequently cited species was A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora with 20 use-reports followed with A. calidophila with 18 use-reports, in which 75% and 61.1% were medicinal (human and veterinary) uses, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3.

List of Aloe species, major use categories, and frequency of citation per use reports (FC). E = Exudate; F = Flower; G = Gel; I = Inflorescence; L = Leaf; LP = Live plant; P = Pedicel; R = Root.

| Scientific name & Voucher No. | Major use category | Sub-category | Use report | Part used | Use description | FC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloe calidophila | Social uses | Memorial | Memorial | LP | Planting on graveyard | 94.44 |

| Reynolds | Weaning | Weaning child from breastfeeding | E | Apply to the nipple/breast | 88.89 | |

| AHU103 | Magic | Belief to increase livestock herd size | LP | Planting at gate of the traditional cattle shelter | 61.11 | |

| Cosmetics | Skin softening | G | Apply on skin as a balm | 22.22 | ||

| Medicines | Endocrine system | Bile duct problem/Jaundice | R | Pulverize with honey & drink | 83.33 | |

| P | Chew & swallow the fluid | 27.78 | ||||

| Infections and infestations | Sexually transmitted infections/STI | L | Smoke-bathe the genitals | 77.78 | ||

| Malaria | E | Fresh exudate taken orally | 44.44 | |||

| R | Pulverize with water & drink filtrate | 44.44 | ||||

| Eye infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 44.44 | |||

| E | Put on the head & apply externally around infected eye | 27.78 | ||||

| Gonorrhea | L | Smoke-bathe the genitals | 38.89 | |||

| Repel flies from infected eye | E | Apply externally all around the eye | 27.78 | |||

| Skin and | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 72.22 | ||

| subcutaneous tissue | Small swelling on skin locally called bocha | L | Warm fresh leaf & keep on small swellings | 61.11 | ||

| Wound of livestock due to carnivore/hyena attack | L | Fresh leaf crushed and tied on wound & smoke-bathed | 55.56 | |||

| Musculo-skeletal system | Bone pain | L | Warm well & keep on painful part repeatedly | 61.11 | ||

| Bone pain of cattles | L | Warm well & keep on painful part repeatedly | 61.11 | |||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Repel flies from wounds | E | Apply externally | 38.89 | |

| Soap making | Soap making | G | Used in small-scale soep production with ingredients | 22.22 | ||

| Food | Metabolic system | Water source | G | Fresh gel eaten as source of water in extremely hot areas | 33.33 | |

| Aloe citrina Carter & Brandham | Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 75.00 |

| Leg and hand swelling | G | Tie onto swollen part | 62.50 | |||

| AHU123 | Wound healing in livestock | E | Apply externally | 75.00 | ||

| Infections and infestations | Eye infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 75.00 | ||

| Malaria | E | Taken orally | 50.00 | |||

| Digestive system | Abdominal disorder | E | Taken orally | 75.00 | ||

| ∗Aloe gilbertii Reynolds ex Sebsebe & Brandham subsp. gilbertii | Medicines | Endocrine system | Bile duct problem/Jaundice | E | Taken orally | 91.67 |

| Digestive system | Colon cleaner | E | Taken orally | 75.00 | ||

| Gastric | L | Fresh young leaf pulverized & filtrate take orally | 58.33 | |||

| Stomach disorder of cattles | L | Fresh young leaf pulverized & filtrate given orally | 41.67 | |||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 75.00 | ||

| AHU102 | Infections and infestations | Eye infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 58.33 | |

| Malaria | L & E | Concocted & taken orally | 25.00 | |||

| Environment al uses | Barrier | Boundary marker | LP | Planting | 75.00 | |

| Soil improver | Soil conservation | LP | Planting on terracing | 66.67 | ||

| Social uses | Memorial | Memorial | LP | Planting on graveyard | 58.33 | |

| ∗,¤Aloe harlana Reynolds | Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound | E | Apply on wound | 83.33 |

| AHU117 | Skin inflammation | G & E | Used as ointment | 27.78 | ||

| Snake and spider bites | Snakebite | L | Pulverized with water & filtrate taken orally | 72.22 | ||

| Infections and infestations | Hair fungus | G | Apply on hair or wash with fresh gel daily | 61.11 | ||

| Skin fungus | G & E | Used as ointment | 50.00 | |||

| Digestive system | Bloated stomach of calltes locally called belelo | L | Fresh leaf pulverized & filtrate given orally | 77.78 | ||

| Colon cleaner | E | Powder (locally called SIBRI) taken orally in water | 27.78 | |||

| Endocrine system | Liver swelling | L | Pulverized and filtrate taken orally | 22.22 | ||

| Spleen swelling/Splenomegaly | L | Pulverized and filtrate taken orally | 22.22 | |||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Repel honeybees during honey harvest | L | Smoked while harvesting the honey to prevent bee stings | 38.89 | |

| Aloe lateritia Engler | Social uses | Cosmetics | Hair wash | G | Make shampoo for hair wash | 66.67 |

| AHU125 | Soften hard skin | G | Scrape the gel & apply on skin | 41.67 | ||

| Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Skin infection | G & E | Apply on skin | 58.33 | |

| Infections and infestations | Eye infection | E | Drop in the eye | 58.33 | ||

| Aloe macrocarpa | Social uses | Cosmetics | Emollient | G | Scrape the gel & apply on skin | 65.63 |

| Todaro | Medicines | Infections and | Skin diseases/fungal | G & E | Apply on skin | 59.38 |

| AHU19 | infestations | Hair fungus | G | Apply on hair or wash with fresh gel | 50.00 | |

| Eye infection | E | Drop in eye | 40.63 | |||

| Infections and infestations | Malaria | E | Collect & drink | 12.50 | ||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Fire burn | G | Apply immediately during an accident | 37.50 | ||

| Wound healing | E | Apply on wound as a cream | 28.13 | |||

| Wound healing of livestock | E | Apply on wound as a cream | 31.25 | |||

| Reproductive system and sex health | Sexual impotency | R | Pulverized, mix with fresh butter and use as ointment & smoke-bathe the penis | 9.38 | ||

| ∗Aloe mcloughlinii | Medicines | Skin and | Wound healing | E | Powdered and applied on wound | 62.50 |

| Chris. | subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing/goats | E | Apply on infected part | 50.00 | |

| AHU161 | Infections and | Eye infections | E | Drop in infected eye | 50.00 | |

| infestations | Antiparasite | E | Powdered solution taken orally | 29.17 | ||

| Snake and spider bites | Snakebite | S & E | Concocted and filtrate taken orally | 29.17 | ||

| Digestive system | Laxative | E | Collect & drink | 20.83 | ||

| ∗Aloe megalacantha Baker subs. megalacantha | Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Skin infection | G & E | Concocted & tied onto the skin | 90.91 |

| AHU24 | Infections and infestations | Eye infection | E | Drop in infected ear | 86.36 | |

| Digestive system | Colon cleaner/locally called sibrii | E | Crystallized & juice made is taken orally in the morning | 81.82 | ||

| Stomach ulcer | E | Powder/sibrii in water taken oral | 54.55 | |||

| Blood and Cardiovascular system | Blood pressure | E | Powder/sibrii of exudate in water solution taken oral | 31.82 | ||

| Musculo-skeletal system | Leg and back pain | L | Cross-section leaf slices warmed & tied on foot while a bit hot | 13.64 | ||

| Environment | Barrier | Boundary marker | LP | Planting | 81.82 | |

| al uses | Boundaries | Fence support | LP | Planting | 68.18 | |

| Soil improver | Soil conservation | LP | Planting on terracing | 54.55 | ||

| Aloe megalacantha Baker subs. | Medicines | Digestive system | Colon cleaner/locally called sibrii | E | Collect fresh exudate, crystallized & Juice made taken orally | 85.71 |

| alticola | Stomach disorder in cattles | L | Pulverized & filtrate taken orally | 57.14 | ||

| AHU162 | Infections and | Eye infection | E | Drop in infected ear | 67.86 | |

| infestations | E | Apply external around the eye | 28.57 | |||

| Ear infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 32.14 | |||

| Tonsillitis | E | Drop on throat | 25.00 | |||

| Itching eye | E | Apply externally around the eye | 21.43 | |||

| Foot and mouth disease | S | Smoke-bathe infected part | 21.43 | |||

| Endocrine system | Bile duct problem locally called hadhoftuu | E | Taken oral | 60.71 | ||

| Diabetics | E | Powder in water solution taken orally | 53.57 | |||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Skin infection | S | Smoke-bathe infected part with wet stem | 57.14 | ||

| Goats skin wound | L | Crush & rub on affected part | 50.00 | |||

| Camel skin wound | L | Crush & rub on affected part | 42.86 | |||

| Skin infection | G & E | Concocted & tied onto infected part | 39.29 | |||

| Itching skin of goats | L | Crush & rub on affected part | 32.14 | |||

| General Ailments with unspecific Symptoms |

Cold problem | L | Pulverized & massage the body | 42.86 | ||

| Cold problem locally called qorraa | S | Smoke-bathe body with fresh leaf until well sweating locally called qayyaa | 28.57 | |||

| Body pain feeling | L | Warm well & keep on the painful part repeatedly | 28.57 | |||

| Weak body feeling | E | Drops in water & drink | 21.43 | |||

| Musculo-skeletal system | Knee pain due to cold | G | Softly massage the knee | 42.86 | ||

| E | Apply on the knee | 28.57 | ||||

| Blood and Cardiovascular system | Clean the blood | E | Drops in water, mix & drink | 21.43 | ||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Honey harvesting | S | Smoke near the bee hive while harvesting | 75.00 | |

| Social uses | Cosmetics | Smoke bath for women | S | Smoke-bathe the genital part with dried and wet stem | 64.29 | |

| Tattoo | Colouring hand and leg/women | S | Smoke bath of hand and leg with wet stem | 28.57 | ||

| ∗Aloe otallensis Baker | Social uses | Weaning | Weaning child from breastfeeding | E | Apply to the nipple/breast | 100.00 |

| AHU107 | Medicines | Endocrine system | Bile duct problem called hadhoftu | L | Pulverized & filtrate given oral | 75.00 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound due to carnivore/hyena attack | L | Burned and blackish ash mixed with butter used as ointment | 75.00 | ||

| Wound healing | E | Apply external | 66.67 | |||

| Hand/leg swelling | L | Warm & put on swollen part | 41.67 | |||

| Digestive system | Colon cleaner | E | Powder in water solution taken orally | 58.33 | ||

| Chicken disease/diarrhea | E | Given orally | 75.00 | |||

| ∗Aloe pirottae | Medicines | Skin and | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 87.50 |

| Berger | subcutaneous tissue | Tropical ulcer | G & E | Concocted & used external as ointment | 70.83 | |

| AHU13 | Infections and | Eye infections | E | Drop in infected eye | 87.50 | |

| infestations | Malaria | E | Powder of exudate in water solution taken orally | 54.17 | ||

| Gonorrhea | E | Mixed with honey and taken oral | 25.00 | |||

| Antiparasite | E | Taken orally | 20.83 | |||

| Endocrine system | Bile duct problem | E | Taken orally | 58.33 | ||

| Gallstone | G & E | Taken orally | 20.83 | |||

| Snake and spider bites | Snakebite | E | Taken orally | 37.50 | ||

| Digestive system | Colon cleaner/SIBRI | E | Powder of exudate in water solution taken orally | 33.33 | ||

| Musculo-skeletal system | Muscular pain | G | Boiled & soft massage painful part | 16.67 | ||

| Social uses | Weaning | Weaning child from breastfeeding | E | Apply to the nipple/breast | 75.00 | |

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Insect repellent | L | Smoking around the area to stifle insects | 62.50 | |

| Mosquito repellent | L | Smoke of dried leaves to stifle mosquitoes | 41.67 | |||

| ∗,◊Aloe pubescens Reynolds | Medicines | Digestive system | Colon cleaner | E | Powder of exudate locally called SIBRI in water solution taken orally | 86.36 |

| AHU06 | Soften alimentary canal | L | Young leaf eaten | 59.09 | ||

| Gastric | G | Fresh gel eaten | 54.55 | |||

| Stomachache/kurtet | R & F | Concocted & filterate taken orally | 18.18 | |||

| Endocrine system | Bile duct problem locally called Hadhoftu | E | Taken orally | 59.09 | ||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound | E | Apllied on dermal wound | 54.55 | ||

| Endocrine system | Liver disease | E | Taken orally | 31.82 | ||

| Infections and infestations | Anthrax | L, F & R | Concocted & given orally | 13.64 | ||

| Sicial uses | Memorial | Graveyard | LP | Planting on graveyards | 72.73 | |

| Environment | Boundaries | Fence support | LP | Planting | 68.18 | |

| al uses | Soil improver | Soil conservation | LP | Planting on mountain slopes along the terrace | 36.36 | |

| Food | Food | Food | G | Fresh gel scraped and eaten | 31.82 | |

| ∗∗Aloe retrospiciens Reynolds & Bally | Vertebrate poisons | Poison | Poison carnivore | E | Concentrated exudate hide in meat to feed hyena | 58.33 |

| AHU160 | Poison | Kill goats if eaten in dry season, due to starvation | L | If eaten in the drought season can kill goats | 41.67 | |

| Poison | Poison rats | E | Dried exudate and apply in rat feed | 25.00 | ||

| Aloe rivae Baker | Social uses | Cosmetics | Body & hair wash | G | Make shampoo for washing | 91.67 |

| AHU115 | Medicines | Snake and spider bites | Snakebite | E | Taken orally | 75.00 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 66.67 | ||

| Cancer | Breast cancer | E | Taken orally | 25.00 | ||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Repel flies | E | Apply externally on wound | 41.67 | |

| ∗∗Aloe rugosifolia Gilbert & Sebsebe | Medicines | Musculo-skeletal system | Bone pain | L | Warmth well & keep on painful part repeatedly | 77.78 |

| AHU113 | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 72.22 | |

| Wound of livestock | E | Apply externally | 61.11 | |||

| Small swelling on skin locally called bocha, on hand and legs | L | Warm & keep on small swellings | 38.89 | |||

| Infections and infestations | Eye infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 44.44 | ||

| Aloe ruspoliana Baker | Vertebrate poisons | Carnivor prevention | Deter carnivore from night shelter of livestock | LP | Planting around livestock night shelter | 87.50 |

| AHU121 | Rodent control | Deter rats due to bad smell | LP | Planting around rats nests | 50.00 | |

| Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Itching skin on goat locally called chito | L | Warm & rub the skin while warmer | 37.50 | |

| Aloe secundiflora | Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Skin infections | E | External use on skin | 88.89 |

| Engler | Wound healing | E | Drop on wound and bandage | 83.33 | ||

| AHU106 | Skin infection of livestock | L & E | Prepared for external use on skin | 77.78 | ||

| Wound on livestock skin | L & E | Prepared & applied to wound | 61.11 | |||

| Musculo-skeletal system | Inflammation in muscles/Rheumatism | G & E | Mix & tie on inflamed part | 38.89 | ||

| Infections and infestations | Ectoparasite | L & E | Concocted for external use on skin | 50.00 | ||

| Malaria | E | Taken orally | 33.33 | |||

| Diarrhea | E | Taken orally | 22.22 | |||

| ∗,◊Aloe tewoldei Gilbert & Sebsebe | Medicines | Musculo-skeletal system | Bone fracture | G | Bandage the gel around to soften the part before traditional fracture medication | 87.50 |

| AHU120 | General Ailments with Unspecific Symptoms | Cold problem | L | Pulverized & filterate taken orally | 87.50 | |

| Digestive system | Stomach disorder | L | Pulverized & filterate taken orally | 87.50 | ||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Itching skin on goat locally called chito | L | Put in fire until very soft then rub on skin | 62.50 | ||

| Social uses | Poison | Crop pest control | E | Powder used in crop storage | 50.00 | |

|

∗Aloe trichosantha subsp. longiflora Gilbert & Sebsebe |

Medicines | Digestive system | Laxative/Purgative, colon cleaner, Constipation | E | Powdered & drink in the form of solution or swallow with banana | 50.98 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Infection on skin or wound/Antidermatosic | E | Apply on infected skin | 33.33 | ||

| Fire burn | G | Applied externally | 9.80 | |||

| AHU05 | Skin hardening/emollient | G & E | Make juicy & apply on skin | 4.90 | ||

| Snake and spider bites | Snakebites antidote | L & E | Concocted with water & taken oral | 23.53 | ||

| Endocrine system | Bile duct problem | L | Pulverized kept for 12 h and drink filtrate/young leaf | 22.55 | ||

| Infections and | Tonsillitis | E | Drops on the throat | 11.76 | ||

| infestations | Malaria | E | Taken orally | 10.78 | ||

| L | Pulverize & filtrate taken orally | 1.96 | ||||

| Eye infection | E | Drop in infected eye | 6.86 | |||

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | After male circumcision | L | Smoke bathed after circumisision to prevent potential infection | 14.71 | ||

| Wound on livestock skin | E | Apply externally on wound | 14.71 | |||

| General Ailments with Unspecific Symptoms | Pain due to cold | G | Massage the pain part softly | 10.78 | ||

| Sensory system | Improve poor sight | E | A drop in eyes | 0.98 | ||

| Reproductive system and sex health | Infertility of man and woman | G | Wash the body and genitalia | 0.98 | ||

| Pregnancy, birth and puerperial | Delayed placenta in cattles | L & R | Concoction given orally | 5.88 | ||

| Social uses | Weaning | Weaning child from breastfeeding | E | Apply to the nipple/breast | 50.00 | |

| Magic | Increase herd size of livestock and camel | L | Smoke-bathe milking utensils | 1.96 | ||

| Illuminant | Lighting bonfire | I | Lighting bonfire/torch with dried sticks used in Christian holidays | 6.86 | ||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Repel flies from wounds | E | Apply on and around the wound | 18.63 | |

| Food | Metabolic system | Relief dehydration in extreme hot condition | G | Make it free from exudate & eaten | 5.88 | |

| ∗Aloe welmelensis Sebsebe & Nordal | Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 75.00 |

| AHU124 | Wound healing for cattles | E | Apply externally | 75.00 | ||

| ∗,¤Aloe yavellana | Social uses | Weaning | Weaning child from breastfeeding | E | Apply to the niple/breast | 94.44 |

| Reynolds | Environment al uses | Soil improver | Soil conservation | LP | Planting on terracing | 88.89 |

| AHU116 | Boundaries | Fence support | LP | Planting | 61.11 | |

| Medicines | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Apply externally | 72.22 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing of livestock | E | Apply externally | 72.22 | ||

| Ectoparasite of livestock | L & E | Concocted for external use on skin | 50.00 | |||

| Snake and spider bites | Snake poison | E | Taken orally | 44.44 | ||

| Materials | Domestic utensils | Mosquito repellent | L | Smoking around to stifle mosquito | 66.67 | |

| ∗Highly spotted aloe | Medicines | Snake and spider | Snake poison | E | Drink very soon after snakebite | 63.33 |

| AHU53 | bites | Spider poison | E | Drink very soon after spiderbite | 56.67 | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Wound healing | E | Powder apply on wound | 56.67 | ||

| Digestive system | Diarrhea in cattles | L | Pulverized & filtrate given orally | 46.67 | ||

| Materials | Pest control | Crop pest | E | Powdered & applied in traditional crop storage | 36.67 | |

| Unidentified | Medicines | Infections and | Hair fungus | G | Apply on hair | 83.33 |

| AHU51 | infestations | Tonsillitis | E | Drop in the throat | 61.11 | |

| Endocrine system | Diabetics | E | Powder in solution & drink daily morning | 72.22 | ||

| Social uses | Cosmetics | Skin softening | G | Apply on skin | 66.67 |

Endemic.

Narrowly endemic.

Endangered.

Near threatened.

Vulnerable.

The highest frequency of citation was 100% recorded for Aloe otallensis leaf exudate used for weaning children from breast-feeding followed with 94.4% for A. yavellana leaf exudate used to treat jaundice, 91.6% for A. rivae leaf gel used for body and hair wash, and 90.9% for A. megalacantha subsp. alticola exudate to treat skin infections (Table 3).

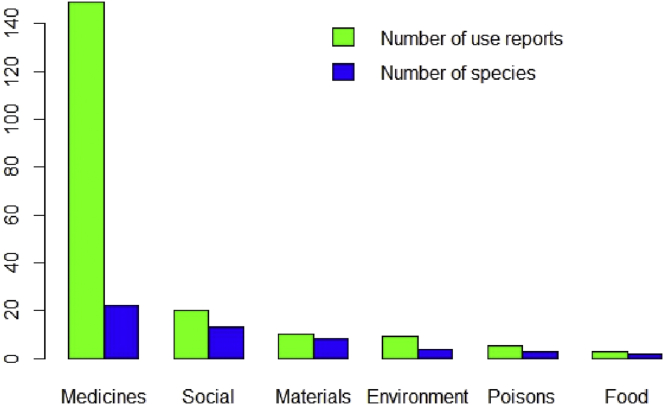

The most frequently cited use of Aloe species in the study areas was for medicines (human and veterinary): 149 use-reports (76%) from 22 Aloe species, with a total number of 1607 citations (use mentions) were recorded. The least use-report was for food use-category: three use-reports (1.5%) from three Aloe species with 19 citations (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The number of use-reports and number of Aloe species used in each major use category.

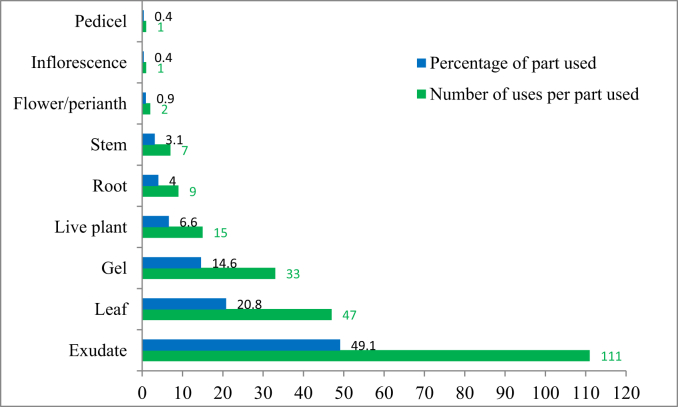

A total of nine different plant parts were used in the diverse bio-cultural uses (Figure 3) within the six major use categories. Leaf exudate was the most frequently sought part, accounting for 111 use-reports (49.1%) in which about 89 (80.2%) were for human medicinal formulations and 12 (11.7%) were for livestock medicinal formulations. That means, 92.9% of exudate were used for medicinal purposes and the remainder in formulations were in social uses and vertebrate poisons categories. In addition, the entire leaf for 47 use-reports (20.8%), which also include the use of exudate as part of entire leaf. This would suggest that the use of exudate exceeds 69% of the plant parts used for medicinal purpose. The fewest use-reports were reported from formulations made from the inflorescence and pedicel, with just a single use-report, which is 0.4% each (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of uses and percentage of each part used for the respective treatment purposes.

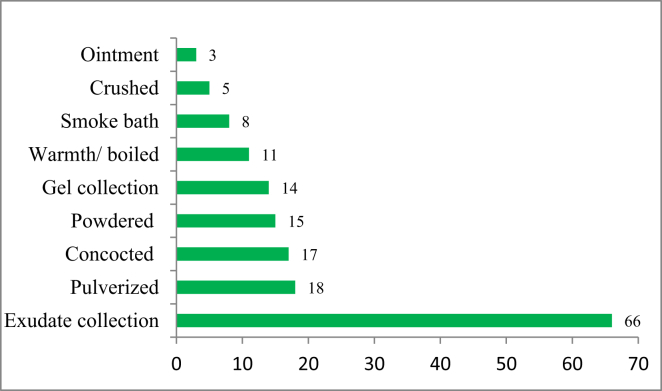

The local communities practiced nine types of preparation methods for medicinal applications, out of these 42% are prepared in the form of pure exudate collection from the fresh leaf to be used for different application followed by pulverization (11.5%) and concoction (10.8%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of preparation in each type of preparation method for medicinal uses.

3.2. Use-reports among cultural communities

The distribution of use-reports among the cultural communities in the study areas showed 161 use-reports for the Oromo community (N = 140), followed with 17 for the Somali community (N = 32), 9 for the Afar community (N = 24), and 9 use-reports for the Harari community (N = 14). In most of the study areas, the medicinal uses of Aloe species were found more popular among the Oromo community, which accounted for 125 medicinal use-reports, in which 77.6% of the total use-report of this community. The fewest uses were reported from the Afar and Harari communities with 9 use-reports each. Among the bio-cultural values, environmental use-reports like boundary marking, soil conservation, and living fence support were documented only from the Oromo community, from four Aloe species. A unique use-report "poisonous to carnivores" was reported by the Somali and Oromo communities for two Aloe species called Aloe retrospiciens Reynolds & Bally and A. ruspoliana Baker, respectively.

The Oromo community used 22 out of the 23 species documented in this study (the exception was A. retrospiciens). The Somali community used four species (A. retrospiciens, A. megalacantha subs. megalacantha, A. mcloughlinii, and A. pirottaei) followed by the Afar community who use two species, A. retrospiciens and A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora and the Harari community who also use two species, A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora and A. macrocarpa.

3.3. Ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural knowledge among gender and age categories

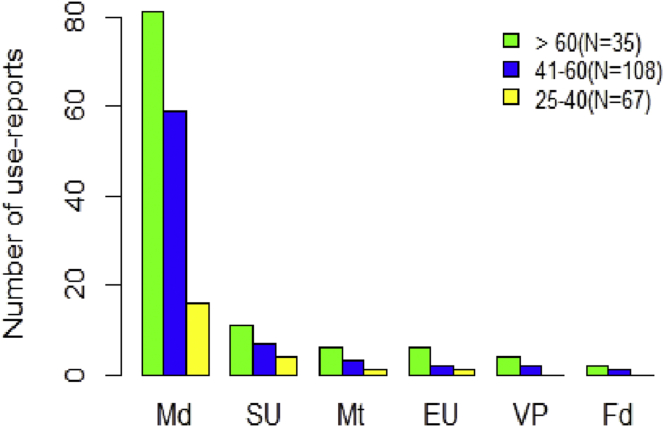

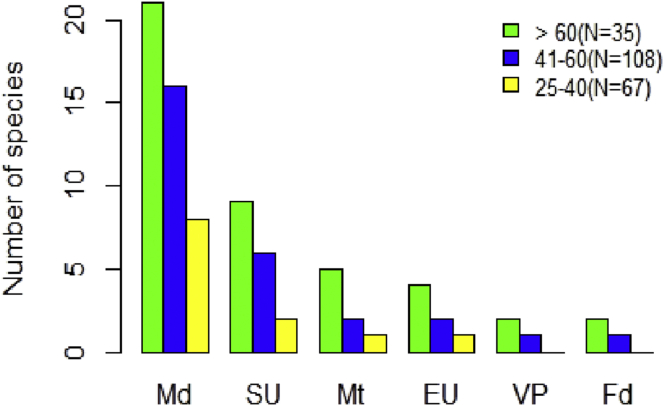

The level of knowledge of Aloe species diversity and use-reports are noticeably lower in the younger age categories compared to elderly informants. For example, out of the total citations (1336) for human medicinal uses, 654 were by elderly people (above 60 years, N = 35) followed with 398 use mention by adults (age 41–60, N = 108) and 284 by young informants (age 25–40, N = 67). The highest number of use-report in all major use categories such as medicines (Md), social uses (SU), materials (Mt), environmental uses (EU), vertebrate poisons (VP), and food (Fd) were reported by elderly people (Figure 5). In the medicines category, 21 species were reported by elderly people (above 60 years, N = 35) followed by 16 species by adults (age 41–60, N = 108) and eight species by young informants (age 25–40, N = 67) (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Number of use-reports in each major use category for each age group (medicines (Md), social uses (SU), materials (Mt), environmental uses (EU), vertebrate poisons (VP), and food (Fd)).

Figure 6.

The number of Aloe species reported in each major use category for each age group (Md), social uses (SU), materials (Mt), environmental uses (EU), vertebrate poisons (VP), and food (Fd)).

The depth of comprehensive bio-cultural knowledge among different age groups indicated that elderly people (above 60 years) had a much deeper knowledge than the two age group ranging from 25 to 40 and 41–60 (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 12.17, df = 3, p = 0.006∗). There is a significant difference in the depth of ethno-medicinal knowledge between the 25–40 age group and the above 60 age group (p = 0.0004∗∗), and a significant difference between 41-60 year olds and the above 60 age group (p = 0.02∗) (p < 0.05). It was observed that many young people in the study areas were found less knowledgeable about the different Aloe species and associated medicinal and bio-cultural values. In addition, men are more knowledgeable on identifying Aloe at the lower taxonomic level and diverse medicinal use-reports than women. The men from all communities had deeper knowledge in the medicinal use category than women (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.002), which is significantly different (p < 0.05). Women were found more knowledgeable than men for cultural uses like, cosmetic (Wilcoxon test, p = 0.06), not significantly different (p > 0.05).

3.4. Informant consensus factor and value indexes

Informant consensus factors (Fic) of the seven major use categories ranged from 0.86 to 0.22. The highest Fic value 0.86 was for medicines with 22 species and 11 use sub-categories, followed by 0.63 for environmental uses with four species and three sub-categories, and least Fic value was 0.22 for materials with eight species and two sub-categories (Table 4).

Table 4.

Major use categories with the corresponding sub-categories, number of Aloe species used and informant consensus factor values.

| Major use categories with sub-categories | No. of sub-category | N. of use reports | No. of citation | No. of species | Fic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicines: Blood and cardiovascular system, cancer, digestive system, infections and infestations, general ailments with unspecific symptoms, endocrine system, snake and spider bites, pregnancy, birth and puerperial, reproductive system and sex health, sensory system, skin and subcutaneous tissue, & musculo-skeletal system | 12 | 146 (76%) | 1607 | 22 | 0.86 |

| Social uses: Weaning, illuminant, magic, memorial, tattoo & cosmetics | 7 | 20 (10.2%) | 276 | 13 | 0.37 |

| Materials: Domestic utensils & soap making | 2 | 10 (5.1%) | 107 | 8 | 0.22 |

| Environmental uses: Soil improver, boundaries, & barrier | 3 | 9 (4.6%) | 112 | 4 | 0.63 |

| Vertebrate Poisons: Poison, carnivore prevention, rodent control, & pest control | 6 | 5 (2.6%) | 37 | 3 | 0.50 |

| Food: Metabolic system & edible | 2 | 3 (1.5%) | 19 | 2 | 0.50 |

Aloe species were compared based on the values of importance metrics. Some species like Aloe calidophila, A. megalacantha subs. alticola, A. pirottae, and A. gilbertii subsp. gilbertii showed higher values across the indices due to be mentioned by a higher number of informants, relatively higher number of use-categories, and larger number of use-reports to elucidate species that were of high importance in all indices (Table 5).

Table 5.

Relative Importance metrics of Aloe species used in the Great Rift Valley floristic regions of Ethiopia.

| Species | UC | UR | UV | RFC | RI | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloe calidophila | 4 | 18 | 11.72 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 6.20 |

| Aloe megalacantha subsp. alticola | 3 | 23 | 10.89 | 0.52 | 0.88 | 5.66 |

| Aloe pirottae | 3 | 14 | 6.92 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 2.06 |

| Aloe gilbertii subsp. gilbertii | 3 | 10 | 6.00 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 1.55 |

| Aloe pubescens | 4 | 12 | 5.86 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 1.49 |

| Aloe megalacantha subsp. megalacantha | 2 | 9 | 5.63 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 1.39 |

| Aloe yavellana | 4 | 8 | 5.00 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 1.10 |

| Aloe harlana | 2 | 10 | 4.83 | 0.48 | 0.57 | 1.01 |

| Aloe secundiflora | 1 | 8 | 4.55 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| Aloe trichosantha subsp. longiflora | 4 | 20 | 3.14 | 0.24 | 0.61 | 0.64 |

| Aloe otallensis | 2 | 7 | 4.92 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.91 |

| Aloe macrocarpa | 2 | 9 | 3.44 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.74 |

| Aloe rivae | 3 | 5 | 3.91 | 0.58 | 0.53 | 0.49 |

| Aloe citrina | 1 | 6 | 4.12 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.55 |

| Aloe rugosifolia | 1 | 5 | 2.94 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.25 |

| Unidentified (AHU51) | 2 | 4 | 2.83 | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.30 |

| Unidentified (AHU53) | 2 | 5 | 2.60 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.28 |

| Aloe tewoldei | 2 | 5 | 2.50 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.18 |

| Aloe mcloughlinii | 1 | 6 | 2.42 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| Aloe lateritia | 2 | 4 | 2.25 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.22 |

| Aloe welmelensis | 1 | 2 | 1.50 | 0.38 | 0.32 | 0.12 |

| Aloe retrospiciens | 1 | 3 | 1.25 | 0.42 | 0.37 | 0.07 |

| Aloe ruspoliana | 2 | 3 | 1.17 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.05 |

UC = number of major use categories per species; UR = number of use-reports per species; UV = use value of a species; RFC = relative frequency of citation for species; RI = relative importance index; CV = cultural value index of species, which considered the three factors i.e. s (species), i (informants), and u (uses).

4. Discussion

4.1. Ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural values of aloes

Most of the Aloe species were reported to have multiple uses, but the majority of uses were medicinal [42, 43]. In this study, it has been shown that most common traditional use of Aloe species was in the traditional health care system. This compares closely with the value of 74% of literature-based use records describing the medicinal uses of Aloe [28] and 73% for human medicines from 11 Aloe species in Tanzania [43]. There are 12 sub-categories under the medicine (Md) major use category like the most cited applications of Aloe species were for skin and subcutaneous tissue ailments accounted for 29.6%, followed with infections and infestations 26.5%, and digestive system 14.5%. Aloe exudates was the most cited Aloe part used in the medicinal uses deserve further investigation into the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. The beneficial health-promoting properties present in the exudates of Aloe leaves are attributed to their diverse phytochemical composition [44]. Phytochemical studies on the genus Aloe indicated that over 200 compounds belonging to different classes such as anthrones, chromones, pyrones, coumarins, alkaloids, glycoproteins, naphthalenes, anthraquinones and flavonoids have so far been reported [44, 45, 46, 47]. These classes of compounds have been shown to possess antiviral, anti-tumor, and antibacterial activities [10, 13, 28, 42]. Numerous in vitro and in vivo pharmacological and clinical trials have been revealed the traditional uses of Aloe including wound healing, anti-ulcer, anti-diabetic, hypoglycaemic, anti-cancer, anti-bacterial, anti-viral, and anti-hyperlipidemic activities [10, 42, 48].

A unique use-report: "poisonous to carnivores" was reported for two Aloe species: Aloe retrospiciens and A. ruspoliana. This study is the second to sample A. retrospiciens, 60 years after the first collection of a type specimen for this species. There was no any data on this species except that it was listed as vulnerable (VU) in IUCN category with an unknown population trend [22]. Meat painted with A. ruspoliana is used as bait to kill hyenas [49]. Similarly, Aloe buettneri, A. lateritia, A. rabaiensis, A. secundiflora, and A. zebrina have been documented as ingredients in arrow poisons throughout Africa [50]. The leaf exudates of these two species have an unpleasant smell and found free from the most common Aloes compound called aloin using TLC profile using pure aloin as standard.

The higher frequency of citations of some use-reports can be explained by the fact that these Aloe species are best known and have long been used by the majority of informants, representing a source of reliability. For example, the highest FC value for A. otallensis used for weaning breast feeding child could be attributed for the more effectiveness of its exudate, which is much bitter than others. Similarly, the local communities in Kenya claimed that Aloe lateritia is not as bitter as A. secundiflora, and hence not as effective [7] so the community has preference of specific Aloe species for the purpose.

Among the 23 Aloe species reported in this study, five species were reported whose gel is used for cosmetic purposes: Aloe calidophila, A. lateritia, A. macrocarpa, A. rivae, and the unidentified/AHU 51. The cosmetic value reported with higher FC for A. rivae makes this species a good candidate for detailed study of its gel. Taxonomic reports have indicated that A. lateritia and A. macrocarpa are grouped in the Saponaria [19] or maculate group, a name that came from the Latin "sapo" meaning soap, as the gel makes a soapy lather in water. The gel of AHU51 is used for cosmetic purposes, which has been observed while making soapy lather in water. Though A. calidophila is not in the Saponaria group, its gel is used for soap making and in few sites of the study areas two women associations were observed cultivating this species and used in small-scale soap production for local market, branded as "Yoya" meaning 'peace' in Borena and labelled to treat skin fungus and infections. It has been reported that the gel of Aloe species exhibited faster wound healing effects [48].

4.2. Use-reports among the cultural communities

People of the five floristic regions use 23 species of Aloe, and the diversity in uses suggests that species are not used interchangeably. The highest number of use-reports, recorded for A. calidophila, A. megalacantha subs. megalacantha, A. trichosantha subsp. longiflora, and A. pirottae could be associated with the wider geographic distribution of species and their use by different ethnic communities, a pattern that has been noted previously in Kenya [7]. The higher number of Aloe species and use-reports from the Oromo community could be attributed to the diverse ecology and the wider geographic distribution of Aloe species in the floristic regions inhabited by the Oromo community as compared to the other three ethnic communities. It was verified that there were no significant difference (p-value = 0.061) between the uses of Aloe species among the three cultural/ethinic communities (Afar, Somali, and Harari).

4.3. Ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural knowledge among gender and age categories

The practice of traditional medicine is restricted to men in Ethiopia [51, 52] and, not surprisingly, men were found to hold deeper knowledge of the medicinal uses of Aloe. However, women were found to be more knowledgeable on the cultural uses of aloes such as weaning children from breastfeeding, cosmetics, colouring hand and leg/tattoo, and body fumigation.

Most of the young and some adult informants were found to be less knowledgeable about the diversity of Aloe species and their uses as compared to majority of adults and elderly informants. This could be attributed to the current cultural transformation, and increasing accessibility of education and health centers in rural areas that has challenged the acquisition of indigenous knowledge among young people. An alternative interpretation is that knowledge accumulates over time, and that older people have had longer to learn about plant uses. Similar results were reported in some other cultural groups in Ethiopia [53, 54] and among users of Aloe species in Tanzania [43]. Some studies indicated that valuable ethno-medicinal information was shared with researchers mostly from informants over 60 years of age [55]. In addition, the knowledge of older people might not have been affected by the need to find new subsistence activities, and was thus preserved without external influence. For example, the dried and powdered exudate of Aloe harlana, A. megalacantha subs. alticola, and A. megalacantha subsp. megalacantha locally known as sibrii, which was used as colon cleaner, were sold in the open local market places of nearby towns. The processing, selling, and use of this local product is mainly restricted to elderly people. The knowledge of medicinal values of most Aloe species was particularly evident among elderly informants and also still retained with the majority of adults, but younger participants showed much less knowledge, and if knowledge gain has indeed slowed down, this could have negative consequences for their conservation in future.

4.4. Informant consensus factor and value indexes

The most popular indices used to evaluate the relative importance of the different species, which are used in the traditional system are based on “informant consensus,” i.e., the degree of agreement among the various interviewees [40, 56]. In this respect, there was a strong consensus for the medicinal value of the leaf exudate. Efficacy of traditional medicinal plants is strongly correlated with Fic value, meaning pharmacologically effective remedies are expected to have greater Fic value, and vice versa [38]. The species with higher values in all indices of UV, RFC, RI, and CV like A. calidophila, A. megalacantha subs. megalacantha, A. gilbertii subsp. gilbertii, and A. pirottae were identified to be the most ethno-medicinal and bio-culturally important species.

5. Conclusion

Aloe species were reported to have multiple uses, but it has been shown that the most common local use was in the traditional health care system. In priority setting for Aloe-based product development and cultivation, species like, A. calidophila, A. megalacantha subsp. alticola, and A. pirottae were identified to be the top three ethno-medicinal and bio-culturally important endemic Aloe species. In addition, unidentified Aloe samples could instigate taxonomic discussion and investigation. More importantly, the unique use-report: "poisonous to carnivores" from two Aloe species called A. retrospiciens and A. ruspoliana could initiate detailed phytochemical and toxicity studies, which have not been done so far, and are of particular importance for this study. In this study, it has been shown that the leaf exudates were highly valued in medicinal applications. Therefore, research interests on medicinal values of Ethiopian endemic aloes need to focus on exudates for phytochemical and pharmacological analysis. In addition, the result showed the unfortunate decline in bio-cultural and ethnomedicinal knowledge between generations in most of the study areas. The deterioration of indigenous knowledge coupled with declining wild populations of most Aloe species could stimulate an urgent ethnobotanical study for in-depth investigation before it is lost. It should be followed with phytochemical and pharmacological analyses in order to give scientific ground to the ethnomedicinal knowledge as well as to signify conservation attention and future potential utilization. In general, the output of this comprehensive ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural knowledge will encourage the community to conserve, manage, and sustainable use Aloe species in the natural habitat as well as through cultivation.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

A. Belayneh, S. Demissew: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

N.F. Bussa: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

D. Bisrat: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Haramaya University through Ministry of Education for postgraduate/PhD studies.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the local communities in general and informants in particular for their various supports and valuable information in the study. Special thanks goes to Dr. Solomon Asfaw for developing standard study area map.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Byng J.W., Chase M.W., Christenhusz M.J.M., Fay M.F., Judd W.S., Mabberley D.J., Sennikov A.N., Soltis D.E., Soltis P.S., Stevens P.F. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;181:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Plant List . 2013. A Working List of All Plant Species.http://www.theplantlist.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grace O.M., Simmonds M.S.J., Smith G.F., Van Wyk A.E. Taxonomic significance of leaf surface morphology in aloe section pictae (xanthorrhoeaceae) Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2009;160:418–428. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morton J.F. Folk uses and commercial exploitation of Aloe leaf pulp. Econ. Bot. 1961;36:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynolds G.W. Aloes Book Fund; Mbabane: 1996. The Aloes of Tropical Africa and Madagascar; p. 537. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grace O.M., Simmonds M.S.J., Smith G.F., van Wyk A.E. Therapeutic uses of aloe L. (Asphodelaceae) in southern Africa. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;119:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorå C.S., Wabuyele E., Grace O.M., Nordal I., Newton L.E. The uses of Kenyan aloes: an analysis of implications for names, distribution and conservation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015;11:85. doi: 10.1186/s13002-015-0060-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar S., Yadav M., Yadav A., Yadav J.P. Impact of spatial and climatic conditions on phytochemical diversity and in vitro antioxidant activity of Indian Aloe vera (L.) Burm.f. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017;111:50–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steenkamp V., Stewart M.J. Medicinal applications and toxicological activities of aloe products. Pharmaceut. Biol. 2007;45:411–420. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia Y., Zhao G., Jia J. Preliminary evaluation: the effects of aloe ferox Miller and Aloe arborescens Miller on wound healing. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:181–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grace O.M. Current perspectives on the economic botany of the genus Aloe L. (Xanthorrhoeaceae) South Afr. J. Bot. 2011;77:980–987. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belayneh A., Asfaw Z., Demissew S., Bussa N.F. Medicinal plants potential and use by pastoral and agro-pastoral communities in Erer Valley of Babile Wereda, Eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-8-42. http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/8/1/42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S., Yadav M., Yadav A., Rohilla P., Yadav J.P. Antiplasmodial potential and quantification of aloin and aloe-emodin in Aloe vera collected from different climatic regions of India. BMC Compl. Alternative Med. 2017;17:369. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1883-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oldfield S.A. CITES; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. Review of Significant Trade: East African Aloes. Document 9.2.2, Annex 4, 14th Meeting of the CITES Plants Committee, Windhoek Namibia, 16–20 February 2004. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO Diet. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2003. Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Technical Report Series 916. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynolds T. Hemlock alkaloids from Socrates to poison aloes. Phytochemistry. 2005;66(12):1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards S., Sebsebe D., Hedberg I. vol. 6. The National Herbarium, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa and Department of Systematic Botany, Uppsala University; Uppsala: 1997. Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sebsebe D., Nordal I., Stabbetorp O.E. Endemism and patterns of distribution of the genus aloe (Aloaceae) in the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Biol. Skr. 2001;54:194–203. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sebsebe D., Nordal I. Shama Books; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2010. Aloes and Other Lilies of Ethiopia and Eritrea. [Google Scholar]

- 20.IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) 2015. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber O., Sebsebe D., Kelbessa E., Kalema J., Crook V. 2013. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T201330A2700027. Downloaded on 05 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber O., Sebsebe D. 2013. Aloe Jacksonii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T201367A2702704. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weber O. 2013. Aloe Harlana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T201403A2705365. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber O. 2013. Aloe mcloughlinii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. e.T201379A2703615. Downloaded on 08 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mukonyi K.W., Situma C.A., Lusweti A., Kyalo S., Erik K. Commercial wild aloe resource base in Kenya and Uganda Drylands as alternative livelihoods source to rural communities. Discov. Innovat. 2007;19:220–230. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sisay A., Yirga A., Redwan J., Habtam G. The importance of aloe debrana plant as a thickening agent for disperse printing of polyester and cotton in textile industry. J. Textile Sci. Eng. 2013;4:147. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teshome D.D. Aloe soap value chain initiative and its effect on livelihood diversification strategy: the case of pastoralists and agro-pastoralists of Borana, Southern Ethiopia. JAD. 2014;4(1):86–136. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grace O.M., Simmonds M.S.J., Smith G.F., Van Wyk A.E. Documented utility and biocultural value of Aloe L. (Asphodelaceae): a review. Econ. Bot. 2009;63:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byg A., Baslev H. Diversity and use de palms in Zahamena, eastern Madagascar. Biodivers. Conserv. 2001;10:951–970. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garibaldi A., Turner N. Cultural Keystone species: implications for conservation and restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2004;9(3):1. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skalli S., Hassikou R., Arahou M. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used for diabetes treatment in Rabat, Morocco. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin G.J. 1995. Ethnobotany: A ‘People and Plants’ Conservation Manual. London. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caruso E., Grace O.M., Krause R., Martin G., Puri R., Rankou H., Tekguc I. In: Conducting and Communicating Ethnobotanical Research: A Methods Manual. Caruso E., editor. Global Diversity Foundation; UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham A.B. Earthscan Publications Ltd; London and Sterling, VA: 2001. Applied Ethnobotany: People, Wild Plant Use and Conservation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cook F.E.M. In: Economic Botany Data Collection Standard. Lock J.M., Prendergast H.D.V., editors. Royal Botanic Gardens; Kew: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cotton C.M. John Wiley and Sons Ltd; Chichester, England: 1996. Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tardío J., Pardo de Santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of southern cantabria, Northern Spain. Econ. Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trotter R.T., Logan M.H. Informants consensus: a new Approach for identifying potentially effective medicinal plants. In: Etkin N.L., editor. Proceedings of Plants in Indigenous Medicine and Diet. Redgrave Publishing Company; Bedford Hill, NY: 1986. pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heinrich M. Ethnobotany and its role in drug development. Review article, phytotherapy research. Phytother Res. 2000;14:479–488. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200011)14:7<479::aid-ptr958>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albuquerque R.F.P., Lucena J.M., Monteiro A.T.N., Florentino C.F.C., Almeida B.R. Evaluating two quantitative ethnobotanical techniques. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2006;4:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reyes-García V., Huanca T., Vadez V., Leonard W., Wilkie D. Cultural, practical, and economic value of wild plants: a quantitative study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ. Bot. 2006;60(1):62–74. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akaberi M., Sobhani Z., Javadi B., Sahebkar A., Emami S.A. Therapeutic effects of Aloe spp. in traditional and modern medicine: a review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016;84:759–772. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amir H.M., Grace O.M., Wabuyele E., Manoko M.L.K. Ethnobotany of aloe L. (Asphodelaceae) in Tanzania, S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019;122:330–335. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cardarelli M., Rouphael Y., Pellizzoni M., Colla G., Lucini L. Profile of bioactive secondary metabolites and antioxidant capacity of leaf exudates from eighteen Aloe species. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017;108:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds T. The compounds in Aloe leaf exudates: a review. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1985;90:157–177. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ermias D. Review of the chemistry of aloes of Africa. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 1996;10(1):89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ombito J.O., Salano E.N., Yegon P.K., Ngetich W.K., Mwangi E.M., Koech G.K. A review of the chemistry of some species of genus Aloe (Xanthorrhoeaceae family) J. Sci. Innov. Res. 2015;4(1):49–53. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lizelle T.F., Mazumder A., Dwivedi A., Gerber M., du Plessis J., Hamman J.H. In vitro wound healing and cytotoxic activity of the gel and whole-leaf materials from selected aloe species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;200:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton L.E. Taxonomic use of the cuticular surface features in the genus aloe (Liliaceae) Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1972;65:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neuwinger H.D. Chapman & Hall; London: 1996. African Ethnobotany: Poisons and Drugs, Chemistry, Pharmacology, Toxicology. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lulekal E., Asfaw Z., Kelbessa E., Van Damme P. Ethnomedicinal study of plants used for human ailments in Ankober district, North Shewa Zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gadisa D., Mesele N., Tesfaye A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by indigenous people in and around Dirre Sheikh Hussein heritage site of South-eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018;220:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yineger H., Yewhalaw D., Teketay D. Ethnomedicinal plant knowledge and practice of the Oromo ethnic group in southwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belayneh A., Bussa N.F. Ethnomedicinal plants used to treat human ailments in the prehistoric place of Harla and Dengego valleys, eastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014;10:18. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-10-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sargin S.A., Buyukcengiz M. Plants used in ethnomedicinal practices in Gulnar district of Mersin, Turkey. J. Herb. Med. 2019;15:100224. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moerman D.E. Agreement and meaning: rethinking consensus analysis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2007;112:451–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.