This cohort study uses data from the National Cancer Database from 2007 to 2016 to investigate the association between breast cancer stage at diagnosis and patient insurance status, age, and race/ethnicity before and after the expansion of Medicaid.

Key Points

Question

Did expansion of Medicaid improve insurance coverage for previously uninsured patients with breast cancer, and is there a difference in cancer stage at diagnosis based on state and insurance status?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1 796 902 women, among patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid, states that expanded Medicaid saw a 9 percentage–point reduction in uninsured patients compared with a 1 percentage–point reduction in nonexpansion states. States that expanded Medicaid had a 3 percentage–point decrease in late-stage breast cancer compared with a 1 percentage–point decrease in nonexpansion states, a significant difference.

Meaning

Expansion of Medicaid was associated with a reduction in the number of uninsured patients with breast cancer and with decreased late-stage breast cancer presentation.

Abstract

Importance

The expansion of Medicaid sought to fill gaps in insurance coverage among low-income Americans. Although coverage has improved, little is known about the relationship between Medicaid expansion and breast cancer stage at diagnosis.

Objective

To review the association of Medicaid expansion with breast cancer stage at diagnosis and the disparities associated with insurance status, age, and race/ethnicity.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from the National Cancer Database to characterize the relationship between breast cancer stage and race/ethnicity, age, and insurance status. Data from 2007 to 2016 were obtained, and breast cancer stage trends were assessed. Additionally, preexpansion years (2012-2013) were compared with postexpansion years (2015-2016) to assess Medicaid expansion in 2014. Data were analyzed from August 12, 2019, to January 19, 2020. The cohort included a total of 1 796 902 patients with primary breast cancer who had private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid or were uninsured across 45 states.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Percent change of uninsured patients with breast cancer and stage at diagnosis, stratified by insurance status, race/ethnicity, age, and state.

Results

This study included a total of 1 796 902 women. Between 2012 and 2016, 71 235 (4.0%) were uninsured or had Medicaid. Among all races/ethnicities, in expansion states, there was a reduction in uninsured patients from 22.6% (4771 of 21 127) to 13.5% (2999 of 22 150) (P < .001), and in nonexpansion states, there was a reduction from 36.5% (5431 of 14 870) to 35.6% (4663 of 13 088) (P = .12). Across all races, there was a reduction in advanced-stage disease from 21.8% (4603 of 21 127) to 19.3% (4280 of 22 150) (P < .001) in expansion states compared with 24.2% (3604 of 14 870) to 23.5% (3072 of 13 088) (P = .14) in nonexpansion states. In African American patients, incidence of advanced disease decreased from 24.6% (1017 of 4136) to 21.6% (920 of 4259) (P < .001) in expansion states and remained at approximately 27% (27.4% [1220 of 4453] to 27.5% [1078 of 3924]; P = .94) in nonexpansion states. Further analysis suggested that the improvement was associated with a reduction in stage 3 diagnoses.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, expansion of Medicaid was associated with a reduced number of uninsured patients and a reduced incidence of advanced-stage breast cancer. African American patients and patients younger than 50 years experienced particular benefit. These data suggest that increasing access to health care resources may alter the distribution of breast cancer stage at diagnosis.

Introduction

The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010 expanded Medicaid coverage to include more of the population aged 18 to 64 years with income at or below 138% of the federal poverty level. Major coverage provisions went into full effect in January 2014 and had the potential to reach as many as 47 million Americans who did not have health insurance.1 The goal of the expansion was to improve timely health care access for previously uninsured adults while working to mitigate the prohibitive costs of care.

Despite passage of this bill, several states debated its legality in the context of state sovereignty over health care, leading to the US Supreme Court decision to uphold the states’ decision-making capacity over Medicaid expansion.1 Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that as of 2018, 37 states (including the District of Columbia) had adopted Medicaid expansion and 14 states had not. Of the 37 expansion states, 32 have plans that cover parents and other adults with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty limit ($29 435 per year for a 3-person family and $17 236 per year for an individual, as of 2019). In the 14 nonexpansion states, the median Medicaid eligibility guideline has remained at 40% of the federal poverty limit ($8532 per year for a 3-person family and $4996 for an individual, as of 2019).2

In the context of a highly prevalent and treatable disease, such as breast cancer, early access to diagnosis and treatment may have a substantial clinical effect, particularly among patient groups with historically poor health care access, such as African American women.3 Our study aimed to delineate the relationship between Medicaid expansion and breast cancer stage at diagnosis, with a particular focus on race/ethnicity-based outcomes.

Methods

Data Source and Cohort

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of summary data from the National Cancer Database public benchmark reports via the American College of Surgeons.4 Included were patients with primary breast cancer diagnosed between 2007 and 2016 who were uninsured or had Medicaid, private insurance, or Medicare and whose race/ethnicity, age, state of residence, and American Joint Commission on Cancer summary stage were recorded. Kaiser Family Foundation data were used to determine which states had expanded Medicaid by the end of 2014. Women living in states that previously expanded Medicaid before the ACA’s expansion in 2014 were excluded from the analysis (District of Columbia, Delaware, Massachusetts, New York, and Vermont). The following states did not have data reported to the National Cancer Database during the time periods examined: Alaska, Arkansas, New Mexico, and Wyoming. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

This study used deidentified, publicly available data from the National Cancer Database and was therefore exempt from institutional review board or ethics committee approval. No informed consent was needed for this National Cancer Database study with deidentified patients.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from August 12, 2019, to January 19, 2020. Stage at diagnosis was dichotomized into early (stage 0, 1, or 2) or late (stage 3 or 4). Stage at diagnosis was compared between patients who were uninsured, had Medicaid or Medicare, or were privately covered during the preexpansion years (2012-2013) and postexpansion years (2015-2016), stratified by race/ethnicity and age. Additionally, data from 2007 to 2011 were included to assess trends of stage over time relative to the pre- and postexpansion years. To assess percentage changes from preexpansion to postexpansion, χ2 analysis was used, with 1-sided P < .05 used as the set point for statistical significance. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to assess significance of state income and employment data, with 1-sided P < .05 used as the set point for statistical significance.

Results

Change in Stage of Breast Cancer by State and Insurance Type

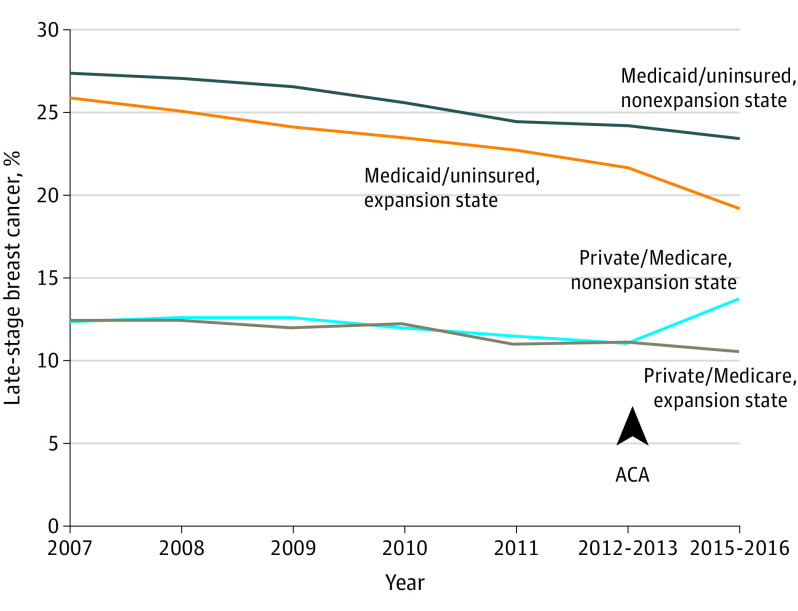

The Figure shows data from a total of 1 796 902 women with primary breast cancer diagnosed between 2007 and 2016 who had Medicaid, Medicare, or private insurance or were uninsured. In all states and at all periods, patients with private insurance or Medicare were about half as likely to present with late-stage breast cancer compared with patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid. Between 2007 and 2012, the percentage of late-stage cancer for patients with private insurance or Medicare in expansion states was 11.7% (90 847 of 776 857) and in nonexpansion states, it was 11.8% (53 975 of 456 600). After passage of the ACA, the incidence remained stable in the expansion states but suddenly rose 2.7% in nonexpansion states (a 2015-2016 late-stage increase to 13.7% [22 415 of 164 085] from 2012-2013 late-stage data showing 11.0% [15 860 of 143 574]). We have no explanation for this, and it was not considered further in this study. In contrast, among patients who were uninsured or had Medicaid, the incidence of advanced-stage cancer at presentation starting in 2007 was 27.4% (1273 of 4650) in nonexpansion states vs 25.9% (1734 of 6687) in expansion states. This percentage decreased by approximately 1 percentage point per year in all states between 2007 and 2012. However, the incidence was always approximately 2 percentage points higher in the nonexpansion states compared with the expansion states, and after passage of the ACA, this difference increased further. Detailed data on the 2012 to 2013 period prior to adoption of the ACA and the 2015 to 2016 period just after adoption of the ACA are shown in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Patients with late-stage cancer who were uninsured or had Medicaid in nonexpansion states exhibited a 1 percentage–point decline from 24.2% to 23.5% (P = .14), whereas patients with late-stage cancer who were uninsured or had Medicaid in the expansion states saw a significant decrease from 21.8% to 19.3% (P < .001). The rest of this article will characterize this decrease in late-stage cancers in the uninsured and Medicaid-covered population.

Figure. Change in Stage of Breast Cancer by State and Insurance Type.

Expansion states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia. Nonexpansion states are Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin. ACA indicates Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Medicaid Coverage of Patients With Breast Cancer by Race and State of Residence

Table 1 shows the association between Medicaid expansion and insurance coverage among the uninsured and Medicaid-covered population broken down by race/ethnicity and by time period. There was a significant difference in the preexpansion baseline insurance coverage between uninsured patients in the expansion states (all races, 4771 of 21 127 [22.6%]) and nonexpansion states (all races, 5431 of 14 870 [36.5%]) (P < .001).

Table 1. Medicaid Coverage of Patients With Breast Cancer by Race and State of Residence.

| Variable | Nonexpansion states | Expansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients | P value | No. (%) of patients | P value | |||

| 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | |||

| White | ||||||

| Uninsured | 2372 (32.4) | 1808 (29.7) | <.001 | 2761 (23.5) | 1445 (11.9) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 4941 (67.6) | 4279 (70.2) | 8969 (76.5) | 10 653 (88.1) | ||

| Total No. | 7313 | 6087 | 11 730 | 12 098 | ||

| African American | ||||||

| Uninsured | 1348 (30.3) | 1004 (25.6) | <.001 | 846 (20.5) | 536 (12.6) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 3105 (69.7) | 2920 (74.4) | 3290 (79.5) | 3723 (87.4) | ||

| Total No. | 4453 | 3924 | 4136 | 4259 | ||

| Hispanic | ||||||

| Uninsured | 1493 (55.3) | 1650 (61.7) | <.001 | 835 (22.9) | 747 (18.5) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 1209 (44.7) | 1024 (38.3) | 2813 (77.1) | 3298 (81.5) | ||

| Total No. | 2702 | 2674 | 3648 | 4045 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | ||||||

| Uninsured | 218 (54.1) | 201 (49.9) | .23 | 329 (20.4) | 271 (15.5) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 184 (45.9) | 202 (50.1) | 1284 (79.6) | 1477 (84.5) | ||

| Total No. | 402 | 403 | 1613 | 1748 | ||

| All races/ethnicities | ||||||

| Uninsured | 5431 (36.5) | 4663 (35.6) | .12 | 4771 (22.6) | 2999 (13.5) | <.001 |

| Medicaid | 9439 (63.5) | 8425 (64.4) | 16 356 (77.4) | 19 151 (86.5) | ||

| Total No. | 14 870 | 13 088 | 21 127 | 22 150 | ||

In the nonexpansion states, the percentage of uninsured individuals after adoption of the ACA decreased slightly in white (1808 of 6087 [29.7%] postexpansion vs 2372 of 7313 [32.4%] preexpansion) and African American (1004 of 3924 [25.6%] vs 1348 of 4453 [30.3%]) patients but increased in Hispanic patients (1650 of 2674 [61.7%] vs 1493 of 2702 [55.3%]). For all races/ethnicities combined, there was no significant difference over time (4663 of 13 088 [35.6%] vs 5431 of 14 870 [36.5%]; P = .12). In contrast, for the expansion states, there was a significant decrease in the uninsured rate in all racial/ethnic groups (2999 of 22 150 [13.5%] vs 4771 of 21 127 [22.6%]; P < .001). These data suggest an association between Medicaid expansion and the preexisting disparity in insurance coverage between expansion and nonexpansion states.

Breast Cancer Stage by Insurance Status

Table 2 shows breast cancer stage individually for uninsured patients, those with Medicaid, and the entire combined group. At every time point, patients with Medicaid had a smaller percentage of late-stage disease compared with uninsured patients. For example, in nonexpansion states, from 2012 to 2013, 1390 of 5431 uninsured patients (25.6%) had late-stage disease vs 2214 of 9439 patients with Medicaid (23.5%). For expansion states, from 2012 to 2013, 1165 of 4771 of uninsured patients (24.4%) had late-stage disease vs 3438 of 16 356 patients with Medicaid (21%).

Table 2. Breast Cancer Stage by Insurance Status.

| Variable | Nonexpansion states | Expansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients | P value | No. (%) of patients | P value | |||

| 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | |||

| Uninsured | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 4041 (74.4) | 3559 (76.3) | .03 | 3606 (75.6) | 2349 (78.3) | .005 |

| Late (3, 4) | 1390 (25.6) | 1104 (23.7) | 1165 (24.4) | 650 (21.7) | ||

| Total, No. | 5431 | 4663 | 4771 | 2999 | ||

| Medicaid | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 7225 (76.5) | 6457 (76.7) | .88 | 12 918 (79.0) | 15 521 (81.0) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 2214 (23.5) | 1968 (23.3) | 3438 (21.0) | 3630 (19.0) | ||

| Total, No. | 9439 | 8425 | 16 356 | 19 151 | ||

| Uninsured and Medicaid groups combined | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 11 266 (75.8) | 10 016 (76.5) | .14 | 16 524 (78.2) | 17 870 (80.7) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 3604 (24.2) | 3072 (23.5) | 4603 (21.8) | 4280 (19.3) | ||

| Total, No. | 14 870 | 13 088 | 21 127 | 22 150 | ||

For uninsured patients, there was a slight decrease in late-stage cancer between the pre- and postexpansion periods in all states (1390 of 5431 [25.6%] vs 1104 of 4663 [23.7%] in nonexpansion states and 1165 of 4771 [24.4%] vs 650 of 2999 [21.7%] in expansion states). However, for patients with Medicaid coverage, there was a statistically significant decrease in late-stage disease in expansion states (3438 of 16 356 [21.0%] vs 3630 of 19 151 [19.0%]; P < .001), whereas there was no change in nonexpansion states (2214 of 9439 [23.5%] vs 1968 of 8425 [23.3%]; P = .88). This outcome, in conjunction with a much higher percentage of patients with Medicaid in expansion states, was associated with a significant decrease in late-stage disease among the combined (uninsured plus Medicaid) group in expansion states (from 4603 of 21 127 [21.8%] to 4280 of 22 150 [19.3%]; P < .001) but not in nonexpansion states (from 3604 of 14 870 [24.2%] to 3072 of 13 088 [23.5%]; P = .14). Detailed data on Medicaid coverage and percent late-stage cancer in each individual state are given in eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Change in Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis by Race/Ethnicity, Age, and State

Across all racial/ethnic groups, the percentage of patients with advanced-stage disease decreased in Medicaid expansion states from 21.8% (4603 of 21 127) preexpansion to 19.3% (4280 of 22 150) postexpansion (P < .001), whereas it only decreased from 24.2% (3604 of 14 870) to 23.5% (3072 of 13 088) in nonexpansion states (P = .14). As seen in Table 3, the association was particularly striking in African American patients, in whom the incidence of advanced disease decreased from 24.6% (1017 of 4136) to 21.6% (920 of 4259) in expansion states and remained steady in nonexpansion states (1220 of 4453 [27.4%] vs 1078 of 3924 [27.5%]). In contrast, there was no significant association in the expansion states for Asian/Pacific Islander or Hispanic patients.

Table 3. Change in Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis Among Patients Who Are Uninsured or Have Medicaid by Race, Age, and State.

| Variable | Nonexpansion states | Expansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients | P value | No. (%) of patients | P value | |||

| 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | |||

| White | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 5630 (77.09) | 4730 (77.7) | .98 | 9184 (78.3) | 9830 (81.3) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 1683 (23.0) | 1357 (22.3) | 2546 (21.7) | 2268 (18.7) | ||

| Total, No. | 7313 | 6087 | 11 730 | 12 098 | ||

| African American | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 3233 (72.6) | 2846 (72.5) | .94 | 3119 (75.4) | 3339 (78.4) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 1220 (27.4) | 1078 (27.5) | 1017 (24.6) | 920 (21.6) | ||

| Total No. | 4453 | 3924 | 4136 | 4259 | ||

| Hispanic | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early 0-2) | 2079 (76.9) | 2112 (79.0) | .07 | 2904 (79.6) | 3263 (80.7) | .24 |

| Late (3, 4) | 623 (23.1) | 562 (21.0) | 744 (20.4) | 782 (19.3) | ||

| Total No. | 2702 | 2674 | 3648 | 4045 | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 325 (80.6) | 328 (81.4) | .79 | 1317 (81.6) | 1438 (82.3) | .64 |

| Late (3, 4) | 78 (19.4) | 75 (18.6) | 296 (18.4) | 310 (17.7) | ||

| Total No. | 403 | 403 | 1613 | 1748 | ||

| Age <50 y | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 4306 (74.3) | 3727 (73.5) | .64 | 5937 (77.1) | 6153 (79.3) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 1492 (25.7) | 1345 (26.1) | 1764 (22.9) | 1604 (20.7) | ||

| Total No. | 5798 | 5072 | 7701 | 7757 | ||

| Age ≥50 y | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 6960 (76.7) | 6289 (78.5) | .006 | 10 646 (78.7) | 11 687 (81.2) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 2112 (23.3) | 1727 (21.5) | 2887 (21.3) | 2706 (18.8) | ||

| Total No. | 9072 | 8016 | 13 533 | 14 393 | ||

| All races/ethnicities and ages | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| Early (0-2) | 11 266 (75.7) | 10 016 (76.5) | .14 | 16 524 (78.2) | 17 870 (80.7) | <.001 |

| Late (3, 4) | 3604 (24.3) | 3072 (23.5) | 4603 (21.8) | 4280 (19.3) | ||

| Total No. | 14 870 | 13 088 | 21 127 | 22 150 | ||

Patients younger than 50 years appeared to show an overall improvement in late-stage presentation in expansion states compared with nonexpansion states. In this age group, expansion states saw a reduction in advanced disease from 22.9% (1764 of 7701) preexpansion to 20.7% (1604 of 7757) postexpansion (P < .001), whereas the nonexpansion states had no significant change (1492 of 5798 [25.7%] vs 1345 of 5072 [26.5%]; P = .64). Both expansion (2887 of 13 533 [21.3%] vs 2706 of 14 393 [18.8%]; P < .001) and nonexpansion (2112 of 9072 [23.3%] vs 1727 of 8016 [21.5%]; P < .006) states saw a statistically significant decrease in late-stage disease in patients 50 years of age or older.

Possible Cut Points for Comparing Early and Late Stages of Breast Cancer Among Uninsured Patients and Patients With Medicaid

Table 4 shows various cut points that could be used to dichotomize early- and late-stage breast cancers. Very early disease (stage 0 or 1) increased in both nonexpansion states (6596 of 14 870 [44.4%] preexpansion vs 6096 of 13 088 [46.6%] postexpansion) and expansion states (10 222 of 21 127 [48.4%] vs 11 477 of 22 150 [51.8%]; P < .001 for both). Stage 4 disease was not associated with any improvement for nonexpansion states and was associated with only marginal but nonsignificant improvement for expansion states. The middle approach defining early as stage 0, 1, or 2 and late as stage 3 or 4 seemed to best differentiate the expansion states (early stage, 16 524 of 21 127 [78.2%] vs 17 870 of 22 150 [80.7%]; late stage, 4603 of 21 127 [21.8%] vs 4280 of 22 150 [19.3%]) from the nonexpansion states (early stage, 11 267 of 14 871 [75.8%] vs 10 016 of 13 088 [76.5%]; late stage, 3604 of 14 871 [24.2%] vs 3072 of 13 088 [23.5%]) and suggests an association between Medicaid and a decrease in the incidence of stage 3 disease. Detailed information on each individual stage by age, race/ethnicity, and state is given in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

Table 4. Possible Cut Points for Comparing Early and Late Stages of Breast Cancer Among Patients Who Are Uninsured or Have Medicaid .

| Cancer stage | Nonexpansion states | Expansion states | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of patients | P value | No. (%) of patients | P value | |||

| 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | 2012-2013 | 2015-2016 | |||

| Very early stage (0, 1) | 6596 (44.4) | 6096 (46.6) | <.001 | 10 222 (48.4) | 11 477 (51.8) | <.001 |

| All other stages (2-4) | 8274 (55.6) | 6992 (53.4) | 10 905 (51.6) | 10 673 (48.2) | ||

| Stage | .14 | <.001 | ||||

| Early (0-2) | 11 266 (75.8) | 10 016 (76.5) | 16 524 (78.2) | 17 870 (80.7) | ||

| Late (3, 4) | 3604 (24.2) | 3072 (23.5) | 4603 (21.8) | 4280 (19.3) | ||

| Metastatic | ||||||

| No (0-3) | 13 251 (89.1) | 11 602 (88.6) | .21 | 18 998 (89.9) | 20 049 (90.5) | .04 |

| Yes (4) | 1619 (10.9) | 1486 (11.4) | 2129 (10.1) | 2101 (9.5) | ||

| Total No. | 14 870 | 13 088 | 21 127 | 22 150 | ||

Discussion

Breast cancer remains the most commonly diagnosed cancer among American women, with an estimated 276 480 new cases and 42 170 cancer-related deaths in 2020.5 Evidence has shown that patients with appropriate access to health care are more likely to receive timely diagnosis and treatment6,7 and less likely to present with advanced-stage disease.8,9 Our analyses suggest that, in all states and at all time periods, patients who were uninsured or who had Medicaid were about twice as likely to present with advanced-stage breast cancer compared with those who had private insurance or Medicare. However, within the population of uninsured patients or those with Medicaid, patients with Medicaid were less likely to present with advanced-stage cancer than those who were uninsured. There were preexisting differences between expansion states and nonexpansion states. Between 2007 and 2013, expansion states already had a lower percentage of uninsured patients and patients with late-stage breast cancer. Following the institution of the ACA, however, states that expanded Medicaid saw a further reduction in the percentage of uninsured patients and advanced-stage disease, whereas the nonexpansion states did not.

When examining race-specific data, the benefit was most noticeable in African American patients and least noticeable in Hispanic and Asian patients. Medicaid expansion diminished the disparity in stage at diagnosis between white and African American patients in the expansion states. This result is quite significant given that African American patients generally present with more aggressive cancer with decreased survival.10 Comparatively, Hispanic and Asian/Pacific Islander patients did not see a statistically significant improvement with Medicaid expansion, although their rate of advanced disease was already similar to that of white women. Prior studies have examined health care disparities among Hispanic women pointing to language, health literacy, and citizenship status as major barriers in obtaining health insurance.11,12 Interestingly, data show that despite higher stages at diagnosis relative to white patients, Hispanic patients have similar survival owing to favorable tumor biological characteristics.10

It appears from the results that low-income patients with breast cancer who are uninsured or have Medicaid are better off living in an expansion state rather than a nonexpansion state. There are other economic indicators that are more favorable in expansion states as well. Data from the Kaiser Family Foundation from 2016 (eTable 4 in the Supplement) demonstrate that compared with the expansion states, the nonexpansion states included in this study have overall higher levels of both unemployment (5.0% vs 4.6%, P = .46) and percentage of population falling below the 200% federal poverty limit (36% vs 30%, P = .009).13 Paradoxically, the states that did not expand Medicaid coverage had a larger proportion of people who would have benefited from Medicaid coverage than the states that did expand.

A few recent studies have demonstrated decreases in uninsured patients with cancer and marginal improvement in early-stage diagnoses with Medicaid expansion.14,15 Han et al14 found that across 20 different newly diagnosed cancer types, there was a statistically significant increase in insurance coverage after Medicaid expansion. However, a slight improvement in stage 1 breast cancer diagnoses was not statistically significant. Jemal et al15 also demonstrated a decrease in the percentage of uninsured patients across a variety of cancer types and, with a larger data set, was able to show a marginally significant increase in stage 1 breast cancer diagnoses. Both of these studies used the last 2 quarters of 2014 as the postexpansion time period, and neither considered race/ethnicity. Our study results suggest an improvement in cancer stage at diagnosis through evaluating a longer duration of time after Medicaid expansion and analyzing its association with advanced-stage disease rather than just very early disease.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Because we used summary data, we did not have individual patient data and could therefore only stratify by 3 variables. This limited the ability to perform multivariable or adjusted analysis.

Granular data on screening and diagnostic practices pre- and postexpansion are unavailable in this data set and, therefore, the mechanism of action for the benefit is unknown. Our data do suggest that Medicaid works primarily by lowering the incidence of stage 3 disease. It seems likely that increased access to health care may allow patients with palpable stage 2 disease to be diagnosed before it becomes stage 3. Additionally, stage 0 and 1 disease were lowered slightly in both expansion and nonexpansion states. A recent study showed that mammography screening increased slightly in both expansion and nonexpansion states, but it was not related to Medicaid expansion.16 This would fit with our data, as stage 0 and 1 disease are primarily found by mammography screening. Stage 4 disease showed only a marginally significant reduction after ACA adoption. This is plausible, as screening and early detection have generally not been found to lead to a decrease in stage 4 disease.17,18

Conclusions

Overall, our findings are encouraging because they suggest that increasing access to health care resources is associated with lower disease stage at diagnosis, particularly for groups, such as African American women, who have historically experienced more advanced de novo disease.19 However, the results are also discouraging because they suggest that even with improved access to Medicaid, the incidence of advanced disease is still much greater than that with private insurance. This raises concerns that the quality of diagnosis and treatment with Medicaid is not as good as with private insurance or, more likely, that the patients who rely on Medicaid have many other socioeconomic and cultural barriers in addition to problems with access to care.8 It also should be pointed out that there is now good evidence that 20% to 30% of all breast cancers are overdiagnosed, that is, they would never cause any clinical problem if they were not diagnosed.20,21 Almost certainly these overdiagnosed cancers are more common in patients with private insurance than in those with Medicaid.22 Thus, if corrected for overdiagnosis, it is possible that the disparity may not be quite as bad as it seems. More study is needed to resolve the disparity in breast cancer stage at diagnosis; however, increased Medicaid coverage is certainly a good start. As national data on breast cancer survival during the ACA expansion period continue to accrue, investigators may begin to examine the long-term disease outcomes associated with the ACA.

eTable 1. Change in Stage of Breast Cancer by State and Insurance Type

eTable 2. Percent Uninsured and Percent Late Stage Among Breast Cancer Patients by State

eTable 3. Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis by Race, Age and State

eTable 4. 2016 State Demographic Information

References

- 1.Rosenbaum S, Westmoreland TM. The Supreme Court’s surprising decision on the Medicaid expansion: how will the federal government and states proceed? Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1663-1672. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. Kaiser Family Foundation Updated 2018. Accessed August 28, 2019. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

- 3.Fulfilling the potential of cancer prevention and early detection. Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council Updated 2003. Accessed July 2, 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223926/

- 4.NCDB public benchmark reports. Cases diagnosed 2008 -2017.American College of Surgeons Updated 2019. Accessed July 5, 2019. http://oliver.facs.org/BMPub/

- 5.Breast cancer facts & figures 2019-2020. American Cancer Society Updated 2020. Accessed January 6, 2020. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2019-2020.pdf

- 6.Coldman A, Phillips N, Wilson C, et al. . Pan-Canadian study of mammography screening and mortality from breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(11):1-7. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fedewa SA, Yabroff KR, Smith RA, Goding Sauer A, Han X, Jemal A. Changes in breast and colorectal cancer screening after Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS, Swanson FH, Edwards MS. Influence of socioeconomic and cultural factors on racial differences in late-stage presentation of breast cancer. JAMA. 1998;279(22):1801-1807. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.22.1801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lannin DR, Mathews HF, Mitchell J, Swanson MS. Impacting cultural attitudes in African-American women to decrease breast cancer mortality. Am J Surg. 2002;184(5):418-423. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(02)01009-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(2):165-173. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim W, Keefe RH. Barriers to healthcare among Asian Americans. Soc Work Public Health. 2010;25(3):286-295. doi: 10.1080/19371910903240704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health coverage by race and ethnicity: the potential impact of the Affordable Care Act. Kaiser Family Foundation Published 2013. Accessed January 19, 2020. https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-the-potential-impact-of-the-affordable-care-act/

- 13.Demographics and the economy. Kaiser Family Foundation Published 2018. Accessed January 18, 2020. https://www.kff.org/state-category/demographics-and-the-economy/

- 14.Han X, Yabroff KR, Ward E, Brawley OW, Jemal A. Comparison of insurance status and diagnosis stage among patients with newly diagnosed cancer before vs after implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(12):1713-1720. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemal A, Lin CC, Davidoff AJ, Han X. Changes in insurance coverage and stage at diagnosis among nonelderly patients with cancer after the Affordable Care Act. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(35):3906-3915. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alharbi AG, Khan MM, Horner R, Brandt H, Chapman C. Impact of Medicaid coverage expansion under the Affordable Care Act on mammography and pap tests utilization among low-income women. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(15):1685-1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heller DR, Chiu AS, Farrell K, Killelea BK, Lannin DR. Why has breast cancer screening failed to decrease the incidence of de novo stage IV disease? Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(4):E500. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman LA. Breast cancer disparities: socioeconomic factors versus biology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24(10):2869-2875. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5977-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welch HG, Prorok PC, O’Malley AJ, Kramer BS. Breast cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1438-1447. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lannin DR, Wang S. Are small breast cancers good because they are small or small because they are good? N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2286-2291. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1613680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harding C, Pompei F, Burmistrov D, Welch HG, Abebe R, Wilson R. Breast cancer screening, incidence, and mortality across US counties. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1483-1489. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Change in Stage of Breast Cancer by State and Insurance Type

eTable 2. Percent Uninsured and Percent Late Stage Among Breast Cancer Patients by State

eTable 3. Breast Cancer Stage at Diagnosis by Race, Age and State

eTable 4. 2016 State Demographic Information