Abstract

This cohort study uses data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to examine changes in the prevalence of mental health treatment among US adults who screened positive for depression between 2007 and 2016.

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide.1 Yet, most US adults who screen positive for depressive symptoms do not receive treatment.2 In the past decade, expansion of mental health care coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA)3 may have promoted an increase in the treatment of adults with depression. We examined trends in the prevalence of adults who screened positive for depression and the proportion receiving treatment from 2007 to 2016, with consideration of health insurance coverage.

Methods

We used 2007-2016 data from 5 waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), administrated by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,4 to examine proportions of adults aged 19 years or older who screened positive for depression, defined by a score of 10 or higher on PHQ-9, the 9-item depression module of the Patient Health Questionnaire.5 This study was deemed to be exempt from human participants review by the Yale School of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board because all data were deidentified and publicly available. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Among individuals who screened positive for depression, evidence of treatment was considered to be a prescription for an antidepressant medication (using generic names),6 consulting a mental health professional (for reasons not specified), or both. We estimated changes in the prevalence of a positive screen for depression and receipt of treatment for depression among those who screened positive.

To examine linear trends over time, we transformed the survey-year variable from 0 (2007-2008) to 1 (2015-2016).2 Odds ratios associated with this transformed variable represent the change in the odds of treatment among those who screened positive for depression across the entire study period. We calculated unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for changing rates. Covariates included age, sex, and race/ethnicity when estimating the association during the adjusted period. Stata, version 15.1 MP/6-Core (StataCorp) was used for all analyses, and the svy commands were used to account for the complex NHANES sampling design, including unequal probability of selection, clustering, and stratification.

Results

Among adults who screened positive for depression between 2007 and 2016, the mean (SD) age was 46.1 (14.9) years. Most individuals were women (64.6%) and non-Hispanic white (63.6%) and had an educational attainment of a high school diploma or higher (73.0%) and insurance coverage (82.1%). The prevalence of US adults who screened positive for depression did not change significantly from 2007-2008 (8.3%, or 5.3 million adults) to 2015-2016 (7.5%, or 5.2 million adults) (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] for time trends, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.70-1.18).

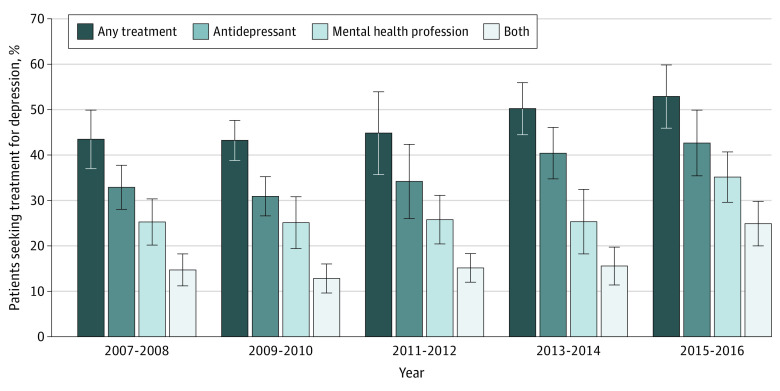

The overall proportion of adults who received any treatment for depression increased from 43.5% in 2007-2008 to 52.9% in 2015-2016 (Figure). This trend was largely owing to both the use of antidepressant therapy and contact with a mental health professional (Table). Having any health insurance was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving treatment (AOR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.49-1.94). This association was reduced following adjustment for survey year (AOR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.05-1.49), suggesting partial mediation of health insurance. No similar significant associations were found among other sociodemographic factors (data not shown).

Figure. Treatment Patterns by Year Among US Adults Who Screened Positive for Depression.

Data are from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Whiskers represent 95% CIs. The proportion of patients receiving any treatment for depression increased from 43.5% in 2007-2008 to 52.9% in 2015-2016 (odds ratio for time trends, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.01-2.19 after controlling for age, sex, and race/ethnicity).

Table. Treatment Patterns and Trends Among US Adults Who Screened Positive for Depression, 2007-2016a.

| Characteristic | Data wave of NHANES | Period association, AOR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007-2008 | 2011-2012 | 2015-2016 | ||

| Sample size, No. | ||||

| Unweighted sample | 5322 | 4816 | 5041 | |

| Weighted population | 64 187 655 | 65 737 534 | 69 617 597 | |

| Taking any psychotropic medication or consulting a mental health professional, % | ||||

| With depression | 51.4 | 52.0 | 60.1 | 1.43 (1.02-1.98) |

| Without depression | 17.8 | 18.7 | 19.3 | 1.08 (0.87-1.35) |

| Any psychotropic medication, % | ||||

| With depression | 43.5 | 46.1 | 53.9 | 1.57 (1.14-2.17) |

| Without depression | 14.6 | 15.2 | 15.6 | 1.10 (0.89-1.36) |

| Antidepressant medication, % | ||||

| With depression | 32.9 | 34.2 | 42.7 | 1.56 (1.09-2.24) |

| Without depression | 10.3 | 11.0 | 10.9 | 1.09 (0.88-1.35) |

| Anxiolytic medication, % | ||||

| With depression | 20.0 | 19.5 | 26.9 | 1.48 (0.94-2.34) |

| Without depression | 5.0 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 1.15 (0.85-1.56) |

| Antipsychotic medication, % | ||||

| With depression | 4.8 | 6.5 | 7.9 | 1.95 (0.78-4.82) |

| Without depression | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.08 (0.61-1.94) |

| Other psychotropic medication, % | ||||

| With depression | 11.0 | 13.0 | 21.8 | 2.60 (1.34-5.03) |

| Without depression | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.4 | 1.35 (0.97-1.87) |

| No. of psychotropic medications, % | ||||

| With depression | ||||

| Monotherapy | 20.9 | 21.2 | 19.7 | 0.87 (0.60-1.26) |

| Polytherapy (≥2 medications) | 22.5 | 24.9 | 35.5 | 2.02 (1.23-3.31) |

| Without depression | ||||

| Monotherapy | 10.5 | 10.4 | 10.1 | 0.93 (0.72-1.20) |

| Polytherapy (≥2 medications) | 4.2 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 1.31 (0.96-1.79) |

| Consulted a mental health professional, % | ||||

| With depression | 25.3 | 25.8 | 35.2 | 1.75 (1.16-2.64) |

| Without depression | 5.9 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 1.32 (0.93-1.88) |

Abbreviations: AOR, adjusted odds ratio; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Data were taken from the NHANES. Trends analysis was adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity.

Discussion

From 2007 to 2016, among adults who screened positive for depression, the proportion who received services increased by almost 10%. An increase in insurance coverage seemed to have a role in promoting treatment access. These trends may reflect increased coverage for mental health care following the ACA Medicaid expansion and Health Insurance Marketplace launch in 2014. Limitations include a cross-sectional survey design that prevented assessment of the timing of insurance coverage and use of mental health services, precluding causal inferences; the absence of information on medication adherence; and a lack of information about treatment outcomes. Nonetheless, this study’s findings show an increase in treatment for depression. Further research is needed to evaluate the potential causal role of the ACA and whether increased depression treatment was associated with improved outcomes.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Depression. Published January 30, 2020. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

- 2.Olfson M, Blanco C, Marcus SC. Treatment of adult depression in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1482-1491. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mechanic D, Olfson M. The relevance of the Affordable Care Act for improving mental health care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016;12:515-542. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention About the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Updated September 15, 2017. Accessed November 27, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/about_nhanes.htm

- 5.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee TG, Rosenheck RA. Psychotropic polypharmacy reconsidered: between-class polypharmacy in the context of multimorbidity in the treatment of depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2019;252:450-457. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]