Abstract

Reactive extrusion of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)/poly(ε-caprolactone) (PHBV/PCL) blends was performed in the presence of cross-linker 1,3,5-tri-2-propenyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione (TAIC) and peroxide. The compatibility between the two biodegradable polymers was significantly improved only when TAIC and peroxide work together, as evidenced by the decreased PCL particle size and blurred interfacial gap between the PHBV and PCL. The mechanical, thermal, morphological, and rheological properties of the compatibilized blends were studied and compared to the blends without TAIC and peroxide. At the optimal TAIC content (1 phr), the elongation at break of the compatibilized blends was 380% that of the PHBV/PCL blend without any additives and 700% that of neat PHBV. The improved interfacial compatibility, decreased PCL particle size, and uniform PHBV crystals are all factors that contribute to improving the toughness of the blend. Through Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and rheological studies, the reaction mechanism is discussed. The study shows that PHBV and PCL are cross-linked by TAIC, resulting in the formation of a PHBV–PCL co-polymer, which improves the compatibility of the blend. The biodegradable polymer blends with high crystallinity and improved toughness prepared in this study are proposed to be used in sustainable packaging or other applications.

Introduction

Over the past several decades, the world has seen a significant increase in the production of plastic products to fit the needs of a changing global economy. As more industries turn to polymers as a cheap and convenient option to package and ship their products around the world, the environmental toll of this increasing plastic usage has become very apparent. This includes the buildup of waste within the environment causing harm to wildlife, as well as the contamination of water and soil. It is reported that 79% of all of these plastics ends up in landfills around the world.1 Landfills are extremely detrimental to the environment due to greenhouse gas emissions, as well as soil and water contamination.2 This has encouraged a strong push toward researching and developing viable biodegradable, biobased replacements for the petrol-based polymers, which currently dominate our daily life.

One such alternative that has garnered the attention of the academic community is poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV)—a member of the poly(hydroxyalkanoate) (PHA) family of bacterial polyesters.3 This is due to some of its attractive properties such as marine biodegradation4,5 and excellent oxygen/vapor barrier properties,6 which are absent in other biodegradable polymers such as polylactide (PLA) and poly(butylene succinate) (PBS). More interesting is that PHBV can be bacterially produced under growth-limiting conditions. Starting from the monomers of hydroxybutyrate and hydroxyvalerate, several polymers can be produced. These include poly(hydroxybutyrate) (PHB), poly(hydroxyvalerate) (PHV), or the co-polymer of the two, PHBV. PHBV is one of the most studied members of this family due to its customizable properties by controlling the hydroxyvalerate content in the chains.7 However, an intrinsic weakness of PHBV is its extreme brittleness,8,9 poor impact strength (IS), and thermal instability,10,11 which make it unfit to serve as a sustainable alternative on its own. One common method to overcome this is to blend PHBV with another polymer to mitigate these weaknesses and overall improve its mechanical and thermal properties.

Due to the weaknesses of PHBV listed above, it is often blended with very ductile, tough polymers to improve these qualities.12 To maintain the biodegradable properties, which make PHBV so attractive to study, other biodegradable polymers are usually chosen for these blends, such as PLA,13,14 PBS,15 poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL),16−19 poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC),20 etc. However, the poor compatibility between different polymers greatly limits the property improvement after blending. To solve this problem, various strategies have been adopted to improve the compatibility or modify the crystal topology of the blends. Plasticizers such as natural oils,21 bisphenol A,22,23 and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG),24 nucleating agents such as boron nitride (BN) and talc,25,26 or in situ cross-linking using dicumyl peroxide (DCP)27 have all been added to PHBV or its blends to modify the properties.

As an elastomer, PCL exhibits superhigh notched impact strength and PHBV/PCL blends have been extensively studied before, including their miscibility,28 thermal properties,29 in vitro degradation,30 and mechanical properties,17 as a target to improve the toughness of PHBV. These previous studies show that PHBV and PCL are immiscible and various strategies, such as using supercritical CO231 or dicumyl peroxides,32,33 have been applied to improve the compatibility. By using supercritical CO2, the PHBV/PCL blend was found to be miscible due to the enhanced interdiffusion of the polymer chains as a result of the action of the supercritical CO2.31 By adding 20 wt % plasticizer (triethyl citrate) and 0.5 wt % dicumyl peroxide to the PHBV/PCL (40/60) blends, Liu and his co-workers found that the elongation at break of PHBV can be increased to ∼130%.34 However, the addition of a plasticizer may hinder the use of the material in long-term applications as a result of plasticizer immigration. On the other hand, reactive extrusion has been shown to be an effective and economic method to improve the compatibility of polymer blends such as PLA/PBS,35 PBS/poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT),36 PHB/PBS,15 etc. via in situ polymer chain modifications in the extruder.37,38 Except for the dicumyl peroxide (DCP), which emits a strong pungent odor, it was found that the other organic peroxide such as Luperox cannot improve the compatibility and mechanical toughness of PHBV/PCL blends especially at high PHBV contents. A PHBV/PCL/peroxide reactive extrusion study was conducted by Cavallaro et al., and it was found that the tensile stress at break was lower for the reacted blends with peroxide due to insufficient interfacial strength between the two polymers.39 Another study on the effect of γ radiation on PHBV/PCL blends also found that the elongation at break of the samples with γ radiation was lower than the blends without radiation, due to the chain scission caused by radiation.40 It seems the addition of peroxide or radiation will cause chain scission rather than the preferred branching or grafting reactions in PHBV.

To solve this problem, a pair of compatibilizers—a free-radical initiator and a cross-linking agent—were used together in the current work with the goal of improving the compatibility between PHBV and PCL. By optimizing the contents of the free-radical initiator, i.e., peroxide, and cross-linking agent, the compatibility between PHBV and PCL can be significantly improved, leading to uniform dispersion and reduced size of the PCL droplets throughout the PHBV matrix. Along with the improved compatibility, the toughness of the blends can be increased, which is different from previous studies. Characterization of the mechanical, thermal, rheological, and morphological properties was completed to identify the optimal blend composition and structure–properties co-relationship in this system.

Results and Discussion

Results—Mechanical, Thermal, and Morphological Properties

As a polymer with high crystallinity, PHBV demonstrates high stiffness (modulus of 3.3 GPa) and tensile strength (41 MPa) but poor elongation at break (∼3.6%) and notched Izod impact strength (21 J/m). Although PCL has been reported as a toughening elastomer that can result in a significant improvement in the toughness of PLA,41 PHBV,17 etc., the injection-molded binary blend of PHBV/PCL 80/20 in this study only showed a limited improvement in impact strength and elongation at break of 28 J/m and 6.7%, respectively (see Table 1). This suggests that the compatibility between PHBV and PCL is poor and interfacial modification is necessary to maximize the toughening effect of PCL on PHBV. Peroxide has been successfully used in reactive extrusion to improve the compatibility of various polymer blends, e.g., PBS/PBAT,42 PLA/PBS/PBAT,43 etc. However, the addition of peroxide to PHBV/PCL blends showed no sign of improvement in the compatibility, which is reflected by the unchanged and reduced ϵb and impact strength. The effect of the peroxide content on the toughness of PHBV/PCL (80/20) blends is shown in Figure S1. This illustrates that peroxide alone cannot improve the toughness of the blends. Likewise, the sole addition of cross-linker 1,3,5-tri-2-propenyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione (TAIC) cannot increase the elongation at break of the blends, as shown by the slightly decreased ϵb of the blends with 1 phr TAIC (Table 1). It can be concluded that either peroxide or TAIC alone cannot effectively improve the compatibility of PHBV/PCL blends.

Table 1. Mechanical Properties of the PHBV and PHBV/PCL Blends.

| impact | tensile |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| blend | impact strength (J/m) | tensile strength (MPa) | Young’s modulus, E (MPa) | elongation at break, ϵb (%) |

| neat PHBV | 21.3 ± 2.5 | 41.7 ± 2.9 | 3319 ± 136 | 3.6 ± 0.9 |

| PHBV/PCL 80/20 | 28.0 ± 2.8 | 37.3 ± 0.9 | 2984 ± 256 | 6.7 ± 1.1 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2 | 25.4 ± 2.6 | 39.2 ± 0.8 | 3114 ± 145 | 6.0 ± 0.8 |

| PCL20–TAIC1 | 22.4 ± 2.2 | 37.2 ± 1.6 | 3114 ± 260 | 5.3 ± 1.0 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC0.5 | 26.1 ± 3.3 | 38.9 ± 0.3 | 2358 ± 107 | 15.2 ± 1.6 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1 | 35.9 ± 6.1 | 36.6 ± 0.9 | 2121 ± 101 | 25.3 ± 7.8 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC3 | 26.9 ± 4.5 | 36.2 ± 0.5 | 2029 ± 57 | 15.0 ± 4.1 |

When peroxide and TAIC are incorporated together, the ductility and toughness of the blends can be significantly improved, as shown by elongation at break (ϵb) and impact strength (IS) in Figure 1a. Both the ϵb and IS of the blends first increased and then decreased with the increasing TAIC content and reached maxima at 1 phr TAIC. At the optimized TAIC content (1 phr), the ϵb of the blend (80/20/0.2/1) was 3.8 times that of the PHBV/PCL (80/20) blend without TAIC and peroxide, increasing from 6.7 to 25.3%, 7 times that of pure PHBV. Meanwhile, the impact strength increased from 21 J/m for pure PHBV to 36 J/m for PHBV/PCL (80/20) blended with 0.2 phr peroxide and 1 phr TAIC. This increased toughness is due to the improved compatibility between PHBV and PCL with the in situ formation of PHBV–PCL co-polymers during reactive extrusion. A decrease in toughness with the higher TAIC content (3 phr) is the result of greater cross-linking density of the polymer chains, which is unfavorable for allowing chain extension during stretching.44 The same phenomenon that over-cross-linking decrease the elongation at break has been reported in the previous studies.45

Figure 1.

Dependence of (a) elongation at break and impact strength; (b) tensile modulus and strength on the cross-linker TAIC contents of PHBV/PCL (80/20) blends with 0.2 phr peroxide.

The increased toughness caused by the PCL was accompanied by a decline of the stiffness of the blends, which is shown in this study. The tensile modulus of the blends is shown in Figure 1b. Along with the increased toughness, the modulus decreased from 3.0 to 2.1 GPa with the increasing TAIC content. It is well known that the mechanical properties of semicrystalline polymers depend on the crystal morphology and crystallinity.46,47 It is expected that the decreased modulus is a result of the decreasing crystallinity or change in the crystal morphology of the blends. Unlike the increased toughness or decreased modulus, the tensile strength of the blends with peroxide and TAIC was identical to that of the PHBV/PCL blend, remaining at 37 MPa.

The statistical analysis of the above mechanical properties was performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) one-way variance analysis with a significance of 0.05. The means plots are represented in the Supporting Information as Figure S2. The statistical analysis results showed that the mechanical properties displayed a significant difference, especially the elongation at break and impact strength, which reached highest at 1 phr TAIC.

The DSC thermograms and crystallinity of the blends are shown in Figure 2. As presented in Figure 2a, the crystallization temperature of PHBV increased by 6 °C from 116 to 122 °C, indicating the enhanced crystallization ability of PHBV after reactive compatibilization.26 In contrast, the crystallization ability of PCL was suppressed with addition of peroxide and TAIC, reflected by a decreased crystallization temperature. Resulting from improved miscibility of PHBV and PCL, the chain mobility at the phase interface was suppressed to favor chain growth during crystallization. Therefore, the crystallization ability of PCL was decreased. The slightly improved crystallization ability of PHBV is probably due to the homogeneous distribution of PCL in the PHBV matrix. More details on the distribution of the PCL phase and its effect on the crystallinity of PHBV will be discussed in the morphology section of this work. As expected, the melting points of PHBV and PCL (as shown in Figure 2b) were reduced due to the imperfect crystals arising from the suppressed chain mobility during crystal growth.48,49 This also indicates that the chain interaction/entanglement of the molecular chains in the two phases is enhanced by the reactive extrusion.

Figure 2.

Thermal crystallization properties of the blends with different peroxide and TAIC contents: (a) cooling at 10 °C/min; (b) heating at 10 °C/min; and (c) dependence of crystallinity of the PHBV and PCL on the TAIC content.

The final crystallinity of the PHBV in the blends (Figure 2c and Table 2) is, however, contrary to the crystallization ability it showed. The crystallinity of PHBV slightly decreased, while the Xc of PCL increased with the increasing TAIC content. The same phenomenon has also been reported in previous research on PHBV/PCL blends39 in which the Xc of PHBV decreased with the increasing PCL content. This is due to the suppressed nucleation of the PHBV by PCL with improved interfacial adhesion.39 First, the crystallization temperature of PHBV is much higher than that of PCL, so the crystallization of PHBV occurred while PCL was still in a molten state. It is well known that the second component in polymer blends greatly influences the primary nucleation of the crystallizing component, known as deactivation of heterogeneity.50 Deactivation of heterogeneity has been reported in polyethylene (PE)/polypropylene (PP) blends,51 as well as PHBV/PCL blends.29 The PCL melt may occupy the crystal growth space of PHBV crystals and lead to the decreased crystallinity of PHBV. As we know, it is hypothesized that the density of the crystal is much higher than that of amorphous parts/melt parts.53 Also, the suppressed nucleation effect is closely related to the interfacial adhesion or phase state between the two components and becomes larger with increasing phase miscibility.29 This is what is present in the system studied in this work, the nucleation of PHBV is probably suppressed by PCL melts with the increasing compatibility, leading to the decreased PHBV crystallinity. The crystallization of PCL happened at 40 °C, in which temperature the PHBV is in the crystal state. Therefore, the crystallization of PCL will not be suppressed by the PHBV. On the other hand, the PHBV crystals may act as a nucleation agent for PCL, resulting to the increased PCL crystallinity.

Table 2. Thermal Properties of the PHBV/PCL Blendsa.

| crystallization temperature (Tc) |

enthalpy (J/g) |

crystallinity

(%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| blend | PHBV | PCL | PHBV | PCL | PHBV | PCL |

| neat PHBV | 121.0 | 84.5 | 77.5 (1.4) | |||

| PHBV/PCL (80/20) | 116.9 | 35.6 | 67.3 | 7.8 | 77.2 (0.9) | 28.7 (0.4) |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2 | 116.5 | 33.6 | 68.2 | 8.1 | 78.2 (1.0) | 29.8 (0.8) |

| PCL20–TAIC1 | 115.2 | 32.2 | 67.7 | 7.9 | 77.6 (0.8) | 28.9 (1.2) |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC0.5 | 122.6 | 32.4 | 67.2 | 7.8 | 77.1 (3.5) | 28.5 (3.2) |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1 | 123.0 | 30.6 | 62.6 | 8.7 | 71.8 (1.2) | 32.1 (1.4) |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC3 | 122.4 | 29.0 | 62.3 | 9.2 | 71.5 (0.6) | 33.1 (1.3) |

Crystallization temperature (Tc) and crystallinity of PHBV and PCL obtained from differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) second heating curves.

For semicrystalline polymers, not only the degree of crystallinity, but also the crystalline form and morphology have a remarkable effect on the performance of the materials.52 Even at the same crystallinity, the properties of the blends with different lamellar organizations will be different. In this regard, the crystal morphology of the blends was checked by polarizing optical microscopy (POM) and is shown in Figure 3. Due to the immiscibility between PHBV and PCL, the binary blend of PHBV/PCL 80/20 exhibited two different crystal topographies in which the imperfect spherulite PHBV crystals are hindered by the PCL phase, as shown in Figure 3A. Interestingly, the crystal growth of PHBV starts at the boundary of the two phases and stops when two crystals meet (this crystal growth of PHBV in the blends is shown in the Supporting Information as Figure S3). The large and irregular crystals are detrimental to the toughness of the polymers by acting as stress concentration points.53 With the improved compatibility between PHBV and PCL, no crystal topography separation can be found in the PCL20/TAIC1/peroxide0.2 blend, as shown in Figure 3D. The more regular spherulite PHBV crystals suggest that PCL crystals did not accumulate at crystal growth fronts but were trapped in the interlamellar regions of the PHBV spherulites. Without an obvious interphase boundary, the PHBV crystals grow simultaneously without interference from the PCL crystal phase. Without interference, the size of the PHBV crystals of the compatibilized sample is larger when compared to that of the PHBV/PCL and PHBV/PCL/peroxide blends. The more perfect and regular crystal topographies in the compatibilized samples are critical for the improved toughness of the blends.

Figure 3.

POM images of the blends: (A) PCL20; (B) PCL20–L0.2; (C) PCL20–TAIC1; and (D) PCL20–L0.2–TAIC1; the scale bar is 100 μm.

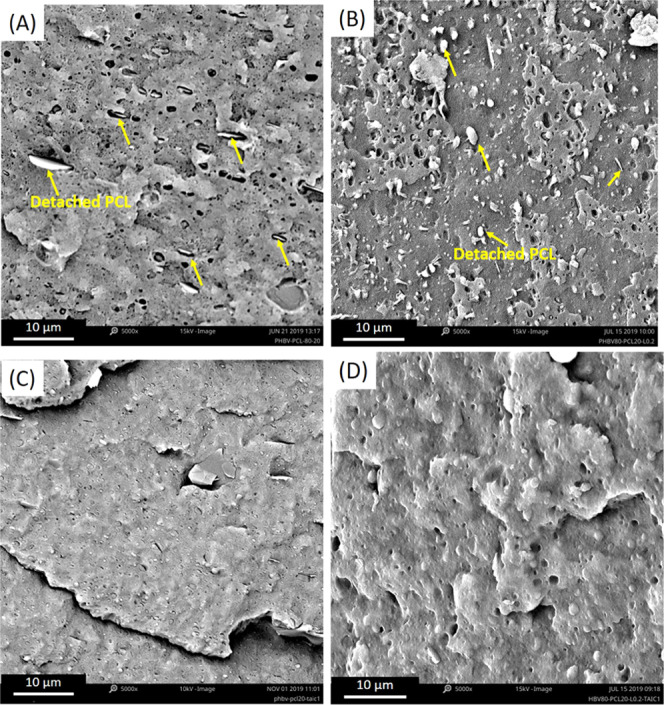

Not only was the crystallization of PHBV changed after reactive extrusion with TAIC and peroxide, but the phase morphology of the blends was also dramatically changed. The morphology of the blend was observed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and is shown in Figure 4. As shown in Figure 4A, the detached PCL particles, which were indicated by the yellow arrow, dispersed in the PHBV matrix with a noticeable interphase gap, resulting from the poor compatibility between these two biopolymers. As a result, the toughening effects of the rubber PCL phase cannot be maximized in the blends. With the independent addition of peroxide or TAIC, the compatibility between PHBV and PCL was not improved, as shown in Figure 4B,C. Large quantities of voids and gaps were generated in these blends during sample fracture, due to the weak interactions between PCL and PHBV. With the addition of peroxide and TAIC together, the sample PHBV80–PCL20–L0.2–TAIC1 showed a completely different morphology (Figure 4D). The blurred interface indicates that the compatibility between the two phases has been dramatically improved. The rubbery PCL is more homogenously dispersed throughout the PHBV with a regular spherical shape.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the blends: (A) PHBV80–PCL20; (B) PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2; (C) PHBV80–PCL20–TAIC1; and (D) PHBV80–PCL20–TAIC1–peroxide0.2.

In addition to the improved compatibility, the size of the rubbery PCL phase also made a great contribution to the toughness of the polymer blends. The particle size was analyzed from the SEM images (shown in Figure S4) of the blends with different TAIC contents. The summary of the particle size and its relationship with toughness (strain at break vs particle size) is shown in Figure 5. A substantial reduction in the PCL particle size was found when increasing the TAIC content to 1 phr, along with the strain at break of the blends reaching its maximum. In addition to the decreased particle size, the dispersion of PCL was more homogeneous, as revealed by the narrower particle distribution (smaller standard deviation). However, the strain at break of the sample with 3 phr TAIC was lower than that of 1 phr TAIC, even although the particle size distribution was similar. This is a result of the increased chain cross-linking of the polymer with the high TAIC content.54

Figure 5.

Dependence of toughness (tensile strain at break) on the rubbery PCL phase size of the sample: PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2 with different TAIC contents.

Discussion—Reaction Mechanism

It is well known that the improved compatibility between the two phases in reactive extrusion results from the in situ formation of co-polymers. To consider the possible reaction between PHBV and PCL in the presence of peroxide and TAIC, the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the reactive blends are shown in Figure S5 in the Supporting Information, and the expanded FTIR spectra in the range of 2700–3200 cm–1 are given in Figure 6a. After reactive extrusion, the FTIR spectra of the samples were identical to those of PHBV80–PCL20, even in the fingerprint range (600–1200 cm–1). This is because the main-chain structures of the PHBV and PCL were not modified in reactive extrusion. According to the previous reports, the main reaction happened between polymers and free radicals in reactive extrusion was the loss of hydrogen in −CH2 or −CH, which resulted to the formation of free radicals, i.e., CH• or −C•, followed by the branching or cross-linking happened between the free radicals.35,42 Therefore, the FTIR spectra in the range of −CH2 and −CH peaks are enlarged and shown in Figure 6 to explore the possible reaction mechanism in our studies. As shown in Figure 6a, with only peroxide, the FTIR spectrum of PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2 was identical to that of PHBV80–PCL20, meaning that no reaction took place in the blends with only peroxide. However, when TAIC was introduced into the blends, the intensity of the peaks at 2870 and 2975 cm–1 decreased and a new peak at 2852 cm–1 appeared for PHBV80–PCL20–TAIC1. The peaks at 2870 and 2975 cm–1 were assigned to be stretching vibration of the −CH2 groups, while the new peaks at 2852 cm–1 were supposed to be the −CH groups. This means that the −CH2 groups on the chains of PHBV and PCL take part in the reaction and are transformed into −CH groups. With the addition of TAIC and peroxide together, the degree of reaction was further increased, expressed as a higher peak intensity at 2852 cm–1 than the peaks at 2870 and 2975 cm–1. From the FTIR spectrum analysis, it was concluded that a possible reaction is the free radicals formed by the peroxide capturing a hydrogen atom in the −CH2 groups, leading to the formation of −CH. Furthermore, the existence of a TAIC-stabilized −CH group results in a further reaction between TAIC and −CH•.

Figure 6.

Reaction between the polymers and functional monomer TAIC: (a) FTIR spectrum of the blends; (b) relaxation time spectrum of the blends: (A) PHBV/PCL (80/20), (B) PCL20–peroxide0.2, and (C) PCL20–TAIC1–peroxide0.2; and (c) possible reaction mechanisms for co-polymer formation in the presence of peroxide and TAIC.

In polymer blend reactive extrusion, excluding the possible reaction between different polymers, there will also be reactions within each component, such as branched PHBV or PCL, and the degree of reaction is affected by the chain activity with free radicals. To detect the chain activity difference between PHBV and PCL, time relaxation spectra of the chains before and after reactive extrusion were studied and are shown in Figure 6b. Compared to the pure blend PHBV/PCL (80/20), the sample with peroxide and TAIC (PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1) exhibited a much higher relaxation spectrum intensity at longer relaxation time (∼1 s). The higher relaxation intensity has been reported to be caused by branching/cross-linking, filler network, and phase morphology.55 The longer relaxation time at ∼1 s was suggested to result from the relaxation of PCL droplets elongated by shear force. The longer relaxation time of the droplets has also been confirmed in PLA/PCL56 and PLA/PBAT57 blends. The 10 times improvement of the relaxation intensity of PCL indicated that the chains were highly entangled and more difficult to relax under shearing force. On the other hand, the decreased droplet size of PCL and its strong interaction with PHBV also resulted in higher relaxation intensity.58

Based on the FTIR spectrum and relaxation time spectrum, the main reaction between the PHBV/PCL and peroxide/TAIC is drawn in Figure 6c. The main reaction took place on the “–CH2” groups in the backbone chains of PHBV and PCL. In the presence of TAIC, the free radicals of “–CH” react with TAIC, and thus the different polymer chains can be linked together, resulting in the formation of “PHBV–PCL” co-polymers. The co-polymers formed contribute to the improved compatibility and reduced interfacial tension between PHBV and PCL. Gelation has been widely reported in the reactive extrusion at high peroxide/cross-linker concentrations.15,27 The effect of cross-linker TAIC concentrations on the gelation contents of the PHBV/PCL blends was studied by Soxhlet extraction and is shown in Figure 7a. The free gel contents of PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2 and PHBV80–PCL20–TAIC1 indicated that no cross-linking happened between PHBV and PCL when either peroxide or TAIC was added into the blends. However, the gel contents increased to 22% when TAIC and peroxide introduced together into PHBV/PCL and they were increased with increasing TAIC concentrations. Since the PCL contents were fixed at 20 wt %, the high gel contents (>20 wt %) means that the cross-linking reactions may be happened both in PHBV and PCL, leading the formation of PHBV–PCL co-polymers or cross-linked PHBV, PCL themselves. To verify the component of gel parts, the FTIR spectrum of the PHBV80–PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1 gelation is given in Figure 7b. The characterization peaks at C=O (1756 cm–1 for C=O) and 1000–1300 cm–1 for C–O–C both in PHBV59 and PCL60 also can be found in the gel FTIR spectra. In the fingerprint range, peaks at 628, which only existed in PHBV, and the peak at 730 cm–1, only for PCL, co-existed in the gel FTIR spectra, indicating that the gel part was a mix of PHBV and PCL or PHBV–PCL co-polymers.

Figure 7.

Properties of gelation in PHBV/PCL blend reactive extrusion: (a) gel contents: sample A: PCL20–peroxide0.2; sample B: PCL20–TAIC1; sample C: PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC0.5; sample D: PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1; and sample E: PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC3; (b) the FTIR of the gel extracted from PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1.

The improved compatibility of the blends can also be determined by their viscoelastic properties.56,61 The storage modulus and complex viscosity of the noncompatibilized and well-compatibilized blends are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Rheological properties of the PHBV/PCL blends at 180 °C: the dependence of (a) storage modulus, (b) complex viscosity, and (c) tan(δ)(G″/G′) of the blends on the frequency and (d) the dependence of storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G″) on the frequency of PHBV/peroxide/TAIC.

The storage modulus and complex viscosity of the PHBV can be increased by the addition of PCL due to the higher melt modulus and viscosity of PCL at 180 °C. However, the dependence of molecular chain behavior on the frequency (or time) was not influenced. The PHBV/PCL (80/20) blends still behaved as a Newtonian fluid in a long time scale, reflected by the similar slopes (close to 2) of the storage modulus vs frequency curves at lower frequencies in Figure 8a. Correspondingly, the viscosity of PHBV and its blend with PCL was independent of frequency at long time movement, resulting from the lack of chain entanglement. The addition of solely TAIC or peroxide cannot improve the chain entanglements of the blends. Without branching or enhanced chain interaction, the blends with 0.2 phr peroxide or 1 phr TAIC showed similar rheological behavior to the PHBV/PCL (80/20) blend, exhibiting no shear thinning. However, the chain behaves completely differently when TAIC and peroxide are added together. The increased frequency dependence of the storage modulus at the low frequency range was found for the PHBV80–PCL20–P0.2–TAIC1 blends, meaning that some internal structures need more time to relax. Clear shear-thinning behavior was observed in this blend at the low frequency range (over a long time scale). The shear thinning is suggested to be caused by the disentanglement of chains due to remaining in a molten state for a significant time. The greater frequency dependence of the storage modulus and apparent shear thinning are caused by the increased level of chain branching of the PHBV/PCL after reactive extrusion. The tan(δ), which is defined as G″/G′ of the blends, is shown in Figure 8c. tan(δ) is reported to be more sensitive to the material viscoelasticity than storage modulus and loss modulus alone.62 With either peroxide or cross-linker, the blends show similar viscoelasticity to the pure PHBV or PHBV/PCL (80/20) blends. The tan(δ) of the blends is higher than 1, indicating that the blends behave more like a viscoelastic liquid. With introduction of TAIC and peroxide together, the tan(δ) decreased to lower than 1, which means that elastic response dominates the melt behavior of the material. The dominant elastic response of the blends with TAIC and peroxide is due to the increased chain branching/entanglement of the polymers. Cross-linker TAIC was required for branching/cross-linking the PHBV, as shown by the rheological properties in Figure 8d. With only peroxide, the storage and loss modulus were decreased and lower than those of neat PHBV. It meant that the existence of peroxide may cause the chain scission of PHBV rather than branching. However, after peroxide was added with TAIC together, the G′ and G″ of the PHBV were significantly improved with higher G′. The higher G′ but not G″ indicated that the melt exhibited high elasticity, which was believed to be caused by chain branching during the process.35

The influence of the TAIC content on the rheological properties of the blends was also studied and is given in Figure S6. The modulus and viscosity of the blends increased with the increasing TAIC content due to the increased chain branching after reactive extrusion. The higher storage modulus and complex viscosity of the blends at 3 phr TAIC indicate that the cross-linking density of the chains is higher compared to the sample with 1 phr TAIC. Unfortunately, the over-cross-linking is detrimental to the tensile toughness of the polymers, resulting in decreased elongation at break as confirmed by the mechanical testing.

Conclusions

The toughness of PHBV is improved by blending with PCL in reactive extrusion with the help of the cross-linker TAIC and peroxide free-radical initiator. This study found that only when the TAIC and peroxide work together can the compatibility between PHBV and PCL be effectively improved. With the improved compatibility, the toughening effects of PCL on PHBV can be realized, resulting in increased elongation at break and impact strength of the PHBV/PCL blends. At an optimal content of TAIC (1 phr) and peroxide (0.2 phr) in this study, the elongation at break of the blends can be increased by 380 and 700%, compared to that of the pure PHBV/PCL blend and neat PHBV. From the morphological studies, the improved toughness is attributed to three different factors: the improved compatibility between PHBV and PCL, the decreased particle size of the toughening phase PCL, and the more uniform spherulite PHBV crystals. Rheological studies show that the storage modulus and complex viscosity were greatly improved by increasing chain branching of PHBV/PCL after reacting with TAIC and peroxide. Through FTIR spectrum analysis, it is suggested that the chain branching is occurring on the “–CH2” site of the backbone chains of PHBV and PCL. Branching of PCL chains and the formation of PHBV–PCL co-polymers occurred during reactive extrusion, and these co-polymers are believed to significantly improve the compatibility between PHBV and PCL. The sustainable toughened PHBV/PCL blends with high crystallinity and melt elasticity are expected to have a role in future packaging applications, via fabrication into biodegradable films.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

PHBV (Y1000P) with 3 mol % HV was obtained from TianAn Biopolymer, China. PCL under the trade name Capa 6800 (Mw = 80 000) was provided by Perstorp Holdings AB (Malmö, Sweden). The peroxide 2,5-bis(tert-butyl-peroxy)-2,5-dimethylhexane, also known as Luperox 101 (Sigma-Aldrich company), and cross-linker 1,3,5-tri-2-propenyl-1,3,5-triazine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione (TAIC) were used together to prepare the PHBV/PCL blends in reactive extrusion.

Sample Preparation

To remove any moisture from the pellets, PHBV were dried in an oven at 70 °C for 12 h and PCL was dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C prior to processing. The pellets were mixed in the appropriate ratio along with any required additives and mechanically mixed in a zipper bag. TAIC and Luperox were added to 0.3 g of acetone to aid mixing with the pellets, followed by evaporating the acetone in a fume hood. The codes for samples with different composition ratios are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Composition of PHBV/PCL Blends Included Additives.

| blend | PHBV (wt %) | PCL (wt %) | Luperox (phr) | TAIC (phr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| neat PHBV | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PHBV/PCL (80/20) | 80 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2 | 80 | 20 | 0.2 | 0 |

| PCL20–TAIC1 | 80 | 20 | 0 | 1 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC0.5 | 80 | 20 | 0.2 | 0.5 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC1 | 80 | 20 | 0.2 | 1 |

| PCL20–peroxide0.2–TAIC3 | 80 | 20 | 0.2 | 3 |

The dried pellets and additives were fed into a DSM explore system (DSM 15cc twin screw microcompounder, Netherlands) for compounding at 175 °C, 100 rpm for 2 min, followed by injecting into molds to produce mechanical test samples. The twin screws had a length to diameter ratio of 18, with a total length of 150 mm. The injection pressure was fixed at 8.0 bar and injection time was 20 s.

Testing and Characterization

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrum

The Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of the materials were determined using a FTIR spectrometer (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Scientific). The scanning range was 64 scans at a resolution of 4 cm–1.

Gel Content

The gel contents of the blends were calculated by the Soxhlet extraction method (ASTM D 2765). The polymer was dissolved by chloroform in reflux for 1 week and the undissolved parts were dried for weighting until weight is not changed. The gel contents were calculated based on the undissolved gel weights. Three specimens for each sample were tested to get the standard deviation.

Mechanical Properties

All tensile and flexural tests were conducted on a universal testing machine (Instron, Massachusetts). Injection-molded samples were formed into type IV tensile bars and were tested at 5.0 mm/min in accordance with ASTM D 682. Flexural tests were conducted in three-point bending mode at a rate of 14.0 mm/min with a support span of 52 mm in accordance with ASTM standard D 790. The results from five test pieces were averaged for each property. Impact testing was carried out using a Zwick/Roell HIT25P impact tester (Ulm, Germany) with a hammer capacity of 2.75 J. Notched Izod samples were tested according to ASTM D 256. The results from six test pieces were averaged to determine the impact strength.

Statistical Analysis

The results obtained from mechanical property tests were analyzed statistically using the ANOVA one-way variance analysis procedure on the OriginPro 9.0. A significance of 0.05 for all of the analyses was used.

Thermal Properties—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC analysis was conducted using a DSC Q200 (TA Instruments, Delaware) machine using a heat–cool–heat cycle. The heating cycles were set to ramp at 10 °C/min up to 200 °C; cooling was set to 10 °C/min down to −60 °C. A nitrogen flow rate of 50 mL/min was used for cooling. The data collected was used to calculate the degree of crystallinity (Xc) of each polymer in a given blend using the following equation

| 1 |

where the subscript X denotes which polymer the crystallinity is being calculated for, ΔHf is the heat of fusion, Wf,X is the weight fraction of PHBV or PCL in the blend, and ΔHX° is the heat of fusion for a 100% crystalline polymer. This value was taken as 109 J/g for PHBV29 and as 136 J/g for PCL.29

Morphological Observation

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted using a Phenom ProX Desktop SEM with an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Samples were prepared via cryo-fracturing and then gold sputter-coated for 12 s prior to SEM observation. A Nikon Eclipse polarized light optical microscope with a Linkam hot stage was used to determine the crystal morphology of the polymer blends. The hot stage was set to heat to 200 °C for 2 min, then cooled down to 60 °C to observe the crystallization of PHBV, and finally down to 40 °C for 10 min to observe the crystallization of PCL. The heating and cooling speeds were set to be 50 °C/min.

Rheological Properties

The rheological properties of the blends were tested in a stress-controlled rheometer (MCR-302, Anton Paar, Germany) at 180 °C in an inert atmosphere. A frequency sweep was performed from 0.1 to 100 rad/s with a strain of 1% to determine the modulus and complex viscosity.

Acknowledgments

The supports from the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA)/the University of Guelph, Bioeconomy for Industrial Uses Research Program (Project # 030255 and 030486); the Ontario Research Fund, Research Excellence Program Round-9 (ORF-RE09) from the Ontario Ministry of Economic Development, Job Creation, and Trade (Project #053970); and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Canada Discovery Grants (Project # 400320) are gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.9b04379.

Elongation at break and notched impact strength, SEM, POM images, FTIR spectrum and rheological curves of the PHBV/PCL blends, statistical analysis results (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Geyer R.; Jambeck J. R.; Law K. L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bläsing M.; Amelung W. Plastics in soil: Analytical methods and possible sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 422–435. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum A.; Zuber M.; Zia K. M.; Noreen A.; Anjum M. N.; Tabasum S. Microbial production of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and its copolymers: a review of recent advancements. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 161–174. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroiné M.; César G.; Le Duigou A.; Davies P.; Bruzaud S. Natural Degradation and Biodegradation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) in Liquid and Solid Marine Environments. J. Polym. Environ. 2015, 23, 493–505. 10.1007/s10924-015-0736-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leathers T. D.; Govind N. S.; Greene R. V. Biodegradation of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) by a Tropical Marine Bacterium, Pseudoalteromonas sp. NRRL B-30083. J. Polym. Environ. 2000, 8, 119–124. 10.1023/A:1014873731961. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thellen C.; Coyne M.; Froio D.; Auerbach M.; Wirsen C.; Ratto J. A. A Processing, Characterization and Marine Biodegradation Study of Melt-Extruded Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Films. J. Polym. Environ. 2008, 16, 1–11. 10.1007/s10924-008-0079-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bugnicourt E.; Cinelli P.; Lazzeri A.; Alvarez V. A. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA): Review of synthesis, characteristics, processing and potential applications in packaging. eXPRESS Polym. Lett. 2014, 791. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2014.82. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alata H.; Aoyama T.; Inoue Y. Effect of Aging on the Mechanical Properties of Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate). Macromolecules 2007, 40, 4546–4551. 10.1021/ma070418i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo M. L.; Righetti M. C. Crystallization-induced formation of rigid amorphous fraction. Polym. Cryst. 2018, 1, e10023 10.1002/pcr2.10023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.-S.; Zhu M.-F.; Wu W.-H.; Qin Z.-Y. Reducing the formation of six-membered ring ester during thermal degradation of biodegradable PHBV to enhance its thermal stability. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 18–24. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2008.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang H.; Wen X.; Miu X.; Li Y.; Zhou Z.; Zhu M. Thermal depolymerization mechanisms of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). Prog. Nat. Sci.: Mater. Int. 2016, 26, 58–64. 10.1016/j.pnsc.2016.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avella M.; Martuscelli E.; Raimo M. Review Properties of blends and composites based on poly(3-hydroxy) butyrate (PHB) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-hydroxyvalerate)(PHBV) copolymers. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 523–545. 10.1023/A:1004740522751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W.; Ma P.; Wang S.; Chen M.; Cai X.; Zhang Y. Effect of partial crosslinking on morphology and properties of the poly(β-hydroxybutyrate)/poly(d,l-lactic acid) blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 1549–1555. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.06.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda M. R.; Misra M.; Mohanty A. K. The effects of process engineering on the performance of PLA and PHBV blends. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2011, 296, 719–728. 10.1002/mame.201000417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P.; Hristova-Bogaerds D. G.; Lemstra P. J.; Zhang Y.; Wang S. Toughening of PHBV/PBS and PHB/PBS Blends via In situ Compatibilization Using Dicumyl Peroxide as a Free-Radical Grafting Initiator. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2012, 297, 402–410. 10.1002/mame.201100224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins M.; Cao Y.; Howell L.; Leeke G. Miscibility in blends of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and poly(ε-caprolactone) induced by melt blending in the presence of supercritical CO2. Polymer 2007, 48, 6304–6310. 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumata K.; Saito T.; Yu F.; Nakamura N.; Inoue Y. The toughening effect of a small amount of poly(ε-caprolactone) on the mechanical properties of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate)/PCL blend. Polym. J. 2011, 43, 484. 10.1038/pj.2011.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulchandani N.; Gupta A.; Masutani K.; Kumar S.; Sakurai S.; Kimura Y.; Katiyar V. Effect of Block Length and Stereocomplexation on the Thermally Processable Poly(ε-caprolactone) and Poly(Lactic acid) Block Copolymers for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 3354 10.1021/acsapm.9b00789. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Campo M.; Quiles-Carrillo L.; Masia J.; Reig-Pérez M.; Montanes N.; Balart R. Environmentally friendly compatibilizers from soybean oil for ternary blends of poly(lactic acid)-PLA, poly(ε-caprolactone)-PCL and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)-PHB. Materials 2017, 10, 1339 10.3390/ma10111339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez E.; Mohanty A. K.; Misra M. Biobased blends of poly(propylene carbonate) and poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate): Fabrication and characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44420 10.1002/app.44420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Audic J. L.; Lemiègre L.; Corre Y. M. Thermal and mechanical properties of a polyhydroxyalkanoate plasticized with biobased epoxidized broccoli oil. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 39983 10.1002/app.39983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fei B.; Chen C.; Wu H.; Peng S.; Wang X.; Dong L. Quantitative FTIR study of PHBV/bisphenol A blends. Eur. Polym. J. 2003, 39, 1939–1946. 10.1016/S0014-3057(03)00114-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fei B.; Chen C.; Wu H.; Peng S.; Wang X.; Dong L.; Xin J. H. Modified poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) using hydrogen bonding monomers. Polymer 2004, 45, 6275–6284. 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khonakdar H. A.; Morshedian J.; Wagenknecht U.; Jafari S. H. An investigation of chemical crosslinking effect on properties of high-density polyethylene. Polymer 2003, 44, 4301–4309. 10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00363-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. J.; Yang H. L.; Wang Z.; Dong L. S.; Liu J. J. Effect of nucleating agents on the crystallization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 2145–2152. 10.1002/app.11023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kai W.; He Y.; Inoue Y. Fast crystallization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) with talc and boron nitride as nucleating agents. Polym. Int. 2005, 54, 780–789. 10.1002/pi.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fei B.; Chen C.; Chen S.; Peng S.; Zhuang Y.; An Y.; Dong L. Crosslinking of poly[(3-hydroxybutyrate)-co-(3-hydroxyvalerate)] using dicumyl peroxide as initiator. Polym. Int. 2004, 53, 937–943. 10.1002/pi.1477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Z.; Yang W.; Ikehara T.; Nishi T. Miscibility and crystallization behavior of biodegradable blends of two aliphatic polyesters. Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) and poly(ε-caprolactone). Polymer 2005, 46, 11814–11819. 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.10.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chun Y. S.; Kim W. N. Thermal properties of poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) and poly(ϵ-caprolactone) blends. Polymer 2000, 41, 2305–2308. 10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00534-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casarin S. A.; Malmonge S. M.; Kobayashi M.; Agnelli J. A. M. Study on In-Vitro Degradation of Bioabsorbable Polymers Poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate)-(PHBV) and Poly(caprolactone)-(PCL). J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2011, 2, 207. 10.4236/jbnb.2011.23026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins M. J.; Cao Y.; Howell L.; Leeke G. A. Miscibility in blends of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) and poly(ε-caprolactone) induced by melt blending in the presence of supercritical CO2. Polymer 2007, 48, 6304–6310. 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.08.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Przybysz M.; Marć M.; Klein M.; Saeb M. R.; Formela K. Structural, mechanical and thermal behavior assessments of PCL/PHB blends reactively compatibilized with organic peroxides. Polym. Test. 2018, 67, 513–521. 10.1016/j.polymertesting.2018.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Garcia D.; Rayón E.; Carbonell-Verdu A.; Lopez-Martinez J.; Balart R. Improvement of the compatibility between poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) and poly(ε-caprolactone) by reactive extrusion with dicumyl peroxide. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 86, 41–57. 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2016.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Gao Z.; Hu X.; Wang Z.; Su T.; Yang L.; Yan S. Blending Modification of PHBV/PCL and its Biodegradation by Pseudomonas mendocina. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 156–164. 10.1007/s10924-016-0795-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji D.; Liu Z.; Lan X.; Wu F.; Xie B.; Yang M. Morphology, Rheology, Crystallization Behavior, and Mechanical Properties of Poly(lactic acid)/Poly(butylene succinate)/Dicumyl Peroxide Reactive Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 1, 39580 10.1002/app.39580. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse R. C.; Speijer A.; Langeraar A. E.; Posthuma de Boer A. Tensile moduli of co-continuous polymer blends. Polymer 1999, 40, 6645–6650. 10.1016/S0032-3861(98)00874-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tzoganakis C. Reactive extrusion of polymers: A review. Adv. Polym. Technol. 1989, 9, 321–330. 10.1002/adv.1989.060090406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur S.; Cisneros-Lopez E. O.; Pin J.-M.; Misra M.; Mohanty A. K. Green Toughness Modifier from Downstream Corn Oil in Improving Poly(lactic acid) Performance. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2019, 3396. 10.1021/acsapm.9b00832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallaro P.; Immirzi B.; Malinconico M.; Martuscelli E.; Volpe M. G. Reactive blending of bioaffine polyesters through free-radical processes. Angew. Makromol. Chem. 1993, 210, 129–141. 10.1002/apmc.1993.052100110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosário F.; Corradini E.; Casarin S. A.; Agnelli J. A. M. Effect of Gamma Radiation on the Properties of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-co-3-Hydroxyvalerate)/Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Blends. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 789–794. 10.1007/s10924-013-0573-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H.-W.; Xiu H.; Gao J.; Deng H.; Zhang Q.; Yang M.-B.; Fu Q. Tailoring Impact Toughness of Poly(l-lactide)/Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PLLA/PCL) Blends by Controlling Crystallization of PLLA Matrix. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 897–905. 10.1021/am201564f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Misra M.; Mohanty A. K. Novel tunable super-tough materials from biodegradable polymer blends: nano-structuring through reactive extrusion. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 2836–2847. 10.1039/C8RA09596E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Misra M.; Mohanty A. K. Super Toughened Poly(lactic acid)-Based Ternary Blends via Enhancing Interfacial Compatibility. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1955–1968. 10.1021/acsomega.8b02587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi N.; Klein A.; Sperling L. Polymer chain rupture and the fracture behavior of glassy polystyrene. Macromolecules 1993, 26, 1019–1026. 10.1021/ma00057a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semba T.; Kitagawa K.; Ishiaku U. S.; Hamada H. The effect of crosslinking on the mechanical properties of polylactic acid/polycaprolactone blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 1816–1825. 10.1002/app.23589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa C.; Scoti M.; Di Girolamo R.; de Ballesteros O. R.; Auriemma F.; Malafronte A. Polymorphism in polymers: A tool to tailor material’s properties. Polym. Cryst. 2020, e10101 10.1002/pcr2.10101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.-j.; Zhang Y.-j.; Zhang J.-q.; Gou Q.-t.; Wang Z.-b.; Chen P.; Gu Q. Crystallization behavior, thermal and mechanical properties of PHBV/graphene nanosheet composites. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2013, 31, 670–678. 10.1007/s10118-013-1248-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-H.; Song F.; Qian D.; He Y.-D.; Nie W.-C.; Wang X.-L.; Wang Y.-Z. Strong and tough fully physically crosslinked double network hydrogels with tunable mechanics and high self-healing performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 349, 588–594. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.05.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C.; Yonglan L.; Baiping R.; Yanxian Z.; Jie M.; Lijian X.; Qiang C.; Jie Z. Super Bulk and Interfacial Toughness of Physically Crosslinked Double-Network Hydrogels. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1703086 10.1002/adfm.201703086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martuscelli E. Influence of composition, crystallization conditions and melt phase structure on solid morphology, kinetics of crystallization and thermal behavior of binary polymer/polymer blends. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1984, 24, 563–586. 10.1002/pen.760240809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gałeski A.; Bartczak Z.; Pracella M. Spherulite nucleation in polypropylene blends with low density polyethylene. Polymer 1984, 25, 1323–1326. 10.1016/0032-3861(84)90384-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mileva D.; Tranchida D.; Gahleitner M. Designing polymer crystallinity: An industrial perspective. Polym. Cryst. 2018, 1, e10009 10.1002/pcr2.10009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knychała P.; Timachova K.; Banaszak M.; Balsara N. P. 50th Anniversary Perspective: Phase Behavior of Polymer Solutions and Blends. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3051–3065. 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Misra M.; Mohanty A. K. Studies on why the heat deflection temperature of polylactide bioplastic cannot be improved by overcrosslinking. Polym. Cryst. 2019, e10088 10.1002/pcr2.10088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F.; Zhang S.; Chen Z.; Zhang B.; Yang W.; Liu Z.; Yang M. Interfacial relaxation mechanisms in polymer nanocomposites through the rheological study on polymer/grafted nanoparticles. Polymer 2016, 90, 264–275. 10.1016/j.polymer.2016.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shin B. Y.; Han D. H. Viscoelastic properties of PLA/PCL blends compatibilized with different methods. Korea–Aust. Rheol. J. 2017, 29, 295–302. 10.1007/s13367-017-0029-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Itry R.; Lamnawar K.; Maazouz A. Rheological, morphological, and interfacial properties of compatibilized PLA/PBAT blends. Rheol. Acta 2014, 53, 501–517. 10.1007/s00397-014-0774-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J.; Machado A.; Moldenaers P.; Maia J. The effect of interfacial properties on the deformation and relaxation behavior of PMMA/PS blends. J. Rheol. 2010, 54, 797–813. 10.1122/1.3439732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y.; Lv J.; Feng J. Spectral Characterization of Four Kinds of Biodegradable Plastics: Poly(Lactic Acid), Poly(Butylenes Adipate-Co-Terephthalate), Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) and Poly(Butylenes Succinate) with FTIR and Raman Spectroscopy. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 108–114. 10.1007/s10924-012-0534-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mofokeng J. P.; Luyt A. S. Morphology and thermal degradation studies of melt-mixed poly(hydroxybutyrate-co-valerate) (PHBV)/poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) biodegradable polymer blend nanocomposites with TiO2 as filler. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 3812–3824. 10.1007/s10853-015-8950-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana H.; Jayaraman K. Rheology of Reactively Compatibilized Polymer Blends with Varying Extent of Interfacial Reaction. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 3412–3419. 10.1021/ma980181d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.; Niu Y.; Yang L.; Xie W.; Li H.; Gan Z.; Wang Z. Morphology, rheology and crystallization behavior of polylactide composites prepared through addition of five-armed star polylactide grafted multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Polymer 2010, 51, 730–737. 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.