ABSTRACT

Importance

Parents take the lead in parent–child interactions and their emotion regulation ability and empathy during parenting may be associated with children’s emotional/behavioral problems. However, the specific mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear.

Objective

The present study aimed to explore the effect of parental empathy and emotional regulation on social competence and emotional/behavioral problems in school‐age children.

Methods

A questionnaire‐based survey was conducted with 274 parents of 8–11‐year‐old children using Achenbach’s Child Behavior Checklist, the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, and the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy.

Results

Children with emotional/behavioral problems (n = 37) had relatively lower social competence than children in a matched control group (n = 37). Compared with the parents of children in the control group, parents of children with emotional/behavioral problems had significantly lower cognitive empathy scores, mainly manifested by low perspective‐taking and online simulation abilities. Mediation analysis showed that parental cognitive empathy had an indirect effect on children’s emotional/behavioral problems through children’s social competence.

Interpretation

Parental empathy may have a subtle influence on the social competence of school‐aged children, which further affects the severity of children’s emotional/behavioral problems.

Keywords: School‐age children, Social competence, Emotional/Behavioral problem, Empathy, Emotion regulation

INTRODUCTION

Emotional/behavioral problems in children, including internalization problems (e.g., anxiety and depression) and externalization problems (e.g., aggression and violence), 1 often cause distress for children and others. A survey in China involving 24 013 urban school‐age children in 22 provinces and municipalities found that the prevalence of childhood behavior problems was approximately 13%. 2 Emotional/behavioral problems in early childhood can have an ongoing effect on physical and mental development and are closely related to antisocial behaviors and psychological problems in adulthood. 3 , 4 Therefore, research on the influencing factors of childhood emotional/behavioral problems has important theoretical and practical value for the early identification and prevention of psychological/behavioral problems and the healthy development of children.

School and home are the two main living environments of school‐age children. Maladaptive interpersonal relationships and unsatisfactory academic performance in school usually cause children high levels of psychological distress. 5 , 6 Several studies have demonstrated a close correlation between lower social competence and greater emotional/behavioral problems in children. 7 , 8 One study found that increased social competence from a training program intervention played a mediating role in reducing behavior problems. 8 Most previous studies have demonstrated the importance of parental capabilities, such as parental empathy and parental emotion regulation, in improving children’s social competence.

Parents structure children’s home environment and implement family parenting. Their abilities to handle their own emotional problems and accept and cope with their children’s emotional problems can substantially affect children’s social competence and mental health. 9 , 10 Research has shown that parental negative emotional expressions can trigger childhood destructive behavior problems. 11 Compared with parents of children without behavior problems, parents of children with a persistent tendency to disobey cannot accurately perceive their own emotions and have poorer emotional regulation and management skills. 12 Although there is evidence that parental regulation and low negative emotionality affect children's social development, 13 , 14 , 15 it remains unclear whether parental emotion regulation has a direct or indirect effect on children's problems, and which types of emotion regulation strategies are more effective.

Parental empathy may be another factor that affects children’s social abilities. Research has shown that parental empathy is positively associated with childhood attachment security and emotional openness. 16 Parents with strong empathy provide their children with a safe foundation from which children can explore their emotional experiences and seek comfort when experiencing emotional distress. Children with good empathy experiences are more likely to develop a functional pattern of emotional expression, rather than emotional avoidance or withdrawal, which helps them to establish more stable interpersonal relationships. 16 Previous studies have focused more on correlations between children's own empathy and their social adaptation and emotional regulation. 17 , 18 Few studies have explored the association of parental empathy with childhood psychological disorders, behavior problems, and internal mechanisms. Recently, Crocetti et al 19 conducted a six‐wave longitudinal study and found an indirect effect of maternal empathy on adolescent antisocial behaviors mediated by parent–adolescent relationships. However, some researchers have argued that empathy includes both “bottom‐up” emotional processes and “top‐down” cognitive processes. 20 , 21 These correspond, respectively, to affective empathy (the ability to produce the same or similar emotional experiences) and cognitive empathy (based on the understanding and perception of the situation or emotional states of others). Although Crocetti et al 19 used the Interpersonal Reactivity Index to assess both cognitive and affective empathy, they did not investigate the unique influences of each of these two components.

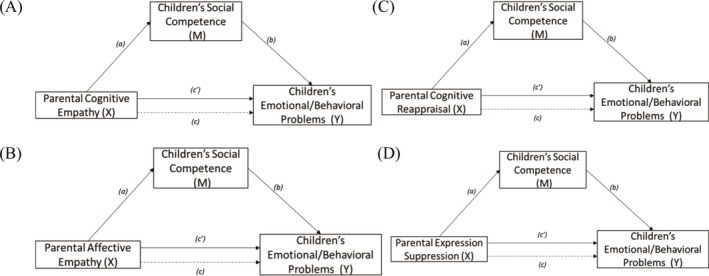

Taken together, previous studies suggest that parents’ ability to regulate their own emotions and foster empathy may have a subtle influence on the social competence of children and the severity of children’s emotional/behavioral problems. However, the internal mechanisms underlying this effect remain unclear. In this study, we aimed to explore the pathways of the effects of parental empathy and emotional regulation on social competence and emotional/behavioral problems of school‐age children. According to the parental meta‐emotion philosophy, 22 , 23 parents’ perceptions, attitudes, and responses to both their own and children’s emotions have important effects on children’s psychological adaptability or mental health. On the basis of this theory and previous findings, 9 , 16 we hypothesized that parents of children with emotional/behavioral problems would score lower on emotional regulation and empathy than parents of healthy children, and that parental empathy and emotional regulation ability would have an indirect effect on children’s emotional/behavioral problems mediated by children’s social competence (conceptual diagrams of these associations are shown in Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual diagram of Andrew Hayes’s mediation model (model 4). (A) and (B) illustrate the hypothetical mediation effect of social competence on the relationship between parental empathy and children’s emotional/behavioral problems. (C) and (D) illustrate the hypothetical mediation effect of social competence on the relationship between parental emotion regulation and children’s emotional/behavioral problems.

METHODS

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of Weifang Medical University. All parents of children participated in the survey provided written informed consent.

Participants

Using a stratified cluster sampling method, we selected parents of 340 8–11‐year‐old children from three primary schools in Weifang, Shandong Province, China to participate in the investigation. Exclusion criteria were families in which children were not living with their parents, single‐parent families, children with no living parents, and parents/children diagnosed with a mental illness. A total of 304 questionnaires were collected, yielding a response rate of 89.4%. After incomplete questionnaires were eliminated, 274 valid questionnaires were used in the final analysis.

Assessments

Achenbach’s Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (parental reports)

The parent‐reported CBCL (for ages 6–18), first developed by Achenbach 24 and adapted by Xin et al 2 for Chinese populations, was used to assess children’s behavioral and emotional problems. The scale contains three modules: general items, social competence, and emotional/behavioral problems. Social competence, which includes the child’s participation in various activities, participation in social organizations, and performance in the school setting, is assessed with 16 items. Higher scores indicate greater social competence. Emotional/behavioral problems are assessed using 113 items rated on a three‐point Likert scale (0 = absent, 1 = occurs sometimes, 2 = occurs often) according to the child’s behavior in the past 6 months. Higher scores represent more severe problems. In addition to the total score, each syndrome consistent with diagnostic categories of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM‐IV) is scored. According to norms for Chinese children, 2 the upper cutoff values of the total scores for boys and girls aged 6–11 years are 42 points and 41 points, respectively. The cutoff values of each syndrome for boys (withdrawn 5–6, somatic complaints 6–7, depressed 9–10, aggressive behavior 19–20, rule‐breaking behavior 7–8, schizoid 5–6, social problems 5–6, compulsivity 8–9, attention problems 10–11) and girls (withdrawn 8–9, somatic complaints 8–9, depressed 3–4, aggressive behavior 18–19, rule‐breaking behavior 2–3, brutality 3–4, schizoid 3–4, attention problems 10–11, sexual problems 3–4) aged 6–11 years differ, and scores above the cutoff value are considered in the borderline clinical and clinical ranges. 2 A Cronbach’s alpha and test‐retest reliability of 0.83–0.94 and 0.88–0.92, respectively, have been demonstrated for the CBCL/6–18, 25 , 26 and a study of 24 013 children demonstrated good reliability and validity for the Chinese version. 2

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) Chinese Revised Version

The ERQ was initially developed by Gross and John 27 and used to measure the two strategies of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The questionnaire contains 10 items rated on a seven‐point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The Chinese revised version of the ERQ shows a test–retest reliability of 0.82 and an internal consistency reliability of 0.85 for cognitive reappraisal, and a test–retest reliability of 0.79 and internal consistency reliability of 0.77 for expressive suppression. 28

Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE)

The QCAE, developed by Reniers et al, 29 comprises 31 items measuring cognitive and affective empathy. Cognitive empathy includes perspective‐taking and online simulation, whereas affective empathy comprises the subscales of emotion contagion, proximal responsivity, and peripheral responsivity. The internal consistency and test–retest reliability of the QCAE for the Chinese population are 0.86 and 0.76, respectively. 30

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to describe sociodemographic and psychological characteristics. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Comparisons of categorical variables and continuous variables were conducted using the Chi‐square test, and the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test and the independent samples t‐test, respectively. Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine correlations between study variables. The PROCESS macro for SPSS, 31 based on ordinary least squares regression, was used to analyze the hypothesized mediation model (Model 4, see Figure 1). The bias‐corrected 95% confidence interval was calculated. For resampling, we used 1000 bootstrap iterations. 32 If the interval does not include zero, the effect is statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

CBCL scores

The 274 children comprised 129 boys (47.1%) and 145 girls (52.9%) aged on average 9.99 years (standard deviation = 0.90). Parent‐reported academic performance was “excellent” for 92 students (33.6%), “good” for 175 students (63.8%), and “adequate” or “failed” for 7 students (2.6%).

Of the 274 children, the median of the total score for emotional/behavioral problems was 13 (interquartile range [IQR] 6–24) in boys and 10 (IQR 4–16) in girls, which was significantly different (P = 0.016). Using the norms for Chinese children aged 6–11 years, 2 the most common behavior problem in girls was depression (11.7%), whereas the main behavior problems in boys were obsessive– compulsive disorder (5.4%), schizoid personality disorder (3.9%), and poor interpersonal communication (3.1%) in our study.

Comparison of social competence between children with emotional/behavioral problems and children in the control group

A total of 37 children with at least one emotional/behavioral problem or a total score exceeding the upper cutoff value were categorized as the problem group. The control group comprised 37 age‐ and sex‐matched children with no detectable problems whose parents were matched with the parents of the problem group for sex and age. The total scores for social competence and the participation scores for various activities and social organizations were significantly lower in the problem group than in the control group (P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

249174017780000249174066294000Comparison of social competence between children with emotional/behavioral problems and children in the control group

| Variables | Group with emotional/behavioral problems (n = 37) | Control group (n = 37) | t | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male/female | 23/14 | 23/14 | – | – |

| Age (years) | 9.7 ± 0.8 | 9.7 ± 0.8 | – | – |

| Participation in various activities | 4.11 ± 2.11 | 7.72 ± 2.23 | −7.138 | < 0.001 |

| Participation in social organizations | 6.36 ± 1.99 | 8.81 ± 1.74 | −5.637 | < 0.001 |

| Academic performance | 5.92 ± 1.01 | 6.20 ± 1.02 | −1.194 | 0.237 |

| Total score of social competence | 16.39 ± 4.25 | 22.73 ± 3.95 | −6.641 | < 0.001 |

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation or n.

Comparison of empathy and emotional regulation ability of parents of children with or without emotional/behavioral problems

Empathy and emotional regulation ability were compared between parents of the 37 children with emotional/behavioral problems and parents of the 37 children without problems. The results of an independent samples t‐test are summarized in Table 2. Compared with the parents of children without problems, the parents of children with problems had significantly lower cognitive empathy scores (t = −2.899, P = 0.005), mainly manifested by low perspective‐taking (t = −2.035, P = 0.046) and online simulation abilities (t = −3.356, P = 0.001). There were between‐group differences in ERQ scores, but these did not reach statistical significance.

Table 2.

Comparison of empathy and emotional regulation ability between parents of children with or without emotional/behavioral problems

| Variables | Group with problems (n = 37) | Control group (n = 37) | t/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother/Father | 28/9 | 30/7 | 0.319 | 0.778 |

| Age (years) | 38.4 ± 3.6 | 37.0 ± 4.4 | 0.792 | 0.379 |

| QCAE score | ||||

| Perspective‐taking | 29.24 ± 3.73 | 31.32 ± 4.97 | −2.035 | 0.046 |

| Online simulation | 27.22 ± 3.14 | 29.81 ± 3.50 | −3.356 | 0.001 |

| Emotion contagion | 11.43 ± 2.47 | 10.73 ± 2.94 | 1.112 | 0.270 |

| Proximal responsivity | 12.35 ± 2.07 | 12.40 ± 2.06 | −0.113 | 0.911 |

| Peripheral responsivity | 9.41 ± 1.69 | 9.86 ± 2.52 | −0.921 | 0.360 |

| Cognitive empathy | 56.46 ± 5.79 | 61.14 ± 7.92 | −2.899 | 0.005 |

| Affective empathy | 33.19 ± 4.65 | 33.00 ± 6.58 | 0.143 | 0.887 |

| ERQ score | ||||

| Cognitive reappraisal | 31.73 ± 4.51 | 34.05 ± 6.91 | −1.714 | 0.092 |

| Expressive suppression | 15.32 ± 4.52 | 16.35 ± 6.97 | −0.752 | 0.455 |

782955‐60007500Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation or n. QCAE, Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy; ERQ, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire.

Correlations of parental empathy and emotional regulation with children’s behavior problems

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the associations of parental empathy and emotion regulation with children’s social competence and emotional/behavioral problems (Table 3). Children’s participation in various activities and social organizations was negatively correlated with total emotional/behavioral problem scores, respectively, indicating that children with lower participation in various activities and social organizations tended to have more emotional/behavioral problems. In addition, parental cognitive empathy was positively correlated with the total score for social competence, and with children’s participation in various activities and social organizations.

Table 3.

Correlation analyses of the association of parental empathy and emotion regulation with children’s social competence and emotional/behavioral problems

| Variables | Total score of emotional/behavioral problems | Total score of social competence | Participation in various activities | Participation in social organizations | Academic performance | Parental cognitive empathy | Parental affective empathy | Parental cognitive reappraisal | Parental expressive suppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score of emotional/79057521145500behavioral problems | – | ||||||||

| Total score of social competence | −0.293** | – | |||||||

| Participation in various activities | −0.249***† | 0.897***† | – | ||||||

| Participation in social organizations | −0.304***† | 0.862***† | 0.619***† | – | |||||

| Academic performance | −0.093 | 0.550***† | 0.305***† | 0.355***† | – | ||||

| Parental cognitive empathy | −0.095 | 0.233***† | 0.224***† | 0.206** | 0.084 | – | |||

| Parental affective empathy | 0.101 | −0.031 | −0.006 | −0.046 | −0.034 | 0.454***† | – | ||

| Parental cognitive reappraisal | 0.020 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.023 | 0.021 | 0.405***† | 0.303***† | – | |

| Parental expressive suppression | −0.043 | 0.023 | 0.061 | 0.001 | −0.047 | 0.259***† | 0.336***† | 0.283***† | – |

7918454000500**P < 0.01 *** P < 0.001 †significant after Bonfferoni correction.

Effects of parental empathy and emotion regulation on childhood social competence and emotional/behavioral problems

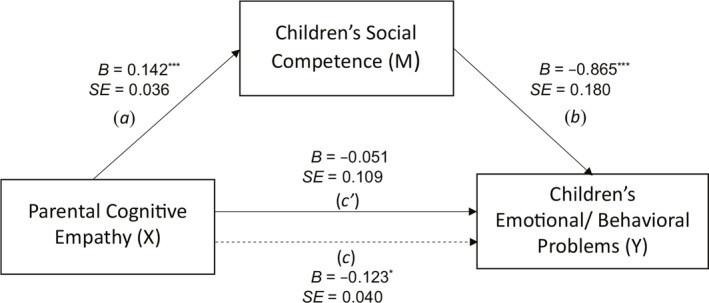

According to our study hypothesis, we established mediation models to examine the effects of parental empathy and emotion regulation on children’s social competence and emotional/behavioral problems. In these models, different components of parental empathy and emotion regulation were the independent variables (X), the total childhood emotional/behavioral problem score was the dependent variable (Y), and children’s social competence was the mediator variable (M) (Figure 1). Model 4 was generated using the PROCESS macro for SPSS 27 ; for resampling, the bootstrap iterations were set at 1000. The verification results showed that only the mediation model in Figure 1A was applicable. The verified model is shown in Figure 2. Children’s social competence had a complete mediating effect on the relationship between parental cognitive empathy and children’s emotional/behavioral problems (Path c) (effect = −0.123, SE = 0.040).

FIGURE 2.

Mediation model of children’s social competence on the relationship between parental cognitive empathy and children’s emotional/behavioral problems. Path c represents the total effect of parental cognitive empathy on children’s emotional/behavioral problems without considering the mediation of social competence. Path c’ represents the indirect effect of parental cognitive empathy on children’s emotional/behavioral problems. * P < 0.05, *** P < 0.001. B, unstandardized regression coefficient; SE, standard error.

DISCUSSION

The present findings show that children with emotional/behavioral problems had significantly lower social competence than children without problems. Compared with parents of children without emotional/behavioral problems, parents of children with problems had lower cognitive empathy. As shown in the mediation analysis, parental cognitive empathy had an indirect effect on children’s emotional/behavioral problems through children’s social competence.

Empathy is closely related to the long‐term social adaptation and mental health of individuals. 33 Parents take the lead in parent–child interactions, so their ability to empathize not only affects their own mental health but also their children’s psychological and behavior problems. 34 , 35 , 36 The present findings reflect this pattern, as cognitive empathy was significantly lower in parents of children with emotional/behavioral problems than in parents of healthy children. Additionally, parental cognitive empathy was positively correlated with children’s social competence, which in turn affected children’s emotional/behavioral problems.

Cognitive empathy is the ability to build a working model of the emotional state of others, whereas affective empathy is the ability to be sensitive to the feelings of others and to experience them indirectly. 2 One study on parental empathy and parent–child relationships showed that parental empathy was positively correlated with childhood narrative coherence. 16 It was concluded that parents with strong empathy provide their children with a safe foundation from which children can explore their emotional experiences and seek comfort when experiencing emotional distress. Children also learn empathy from their parents, which helps them to develop a functional pattern that is more conducive to the establishment of interpersonal relationships and promotes the development of prosocial behaviors. 16 Therefore, parents with a greater ability to recognize their children’s current emotional experiences are more likely to provide sensitive and responsive care that can manage children’s social adaptation problems, such as poor academic performance, relatively isolated social status, and less participation in activities, thus providing early prevention and intervention for childhood emotional and behavioral problems.

Most previous studies have found that parental emotional regulation is related to childhood internally and externally generated emotions and can affect childhood behavior problems (e.g., confrontation, disobedience, and perseverance). 14 However, the current study failed to find a correlation between parental emotional regulation strategies (i.e., cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) and childhood emotional or behavioral problems. Some studies have suggested that emotional regulation tends to have a more direct effect on an individual’s own emotional performance and on the parent–child relationship. 37 , 38 Difficulty in emotional regulation may trigger violence and aggression against others and increase the likelihood of adopting simpler and more immature solutions when managing parent– child relationships. 37 , 38 Contradictory and indifferent parent–child relationships or aggressive management are more likely to cause behavior problems in children. 39 Conversely, difficulty in emotion regulation may cause parents to experience more negative emotions, and parents’ expression of these negative emotions may trigger children’s destructive behavior problems. 11 Therefore, the present results suggest that parental emotional regulation is more likely to be a distal factor that affects children’s social competence and emotional/behavioral problems. Future research on the relationship between parental emotional regulation and childhood emotional/behavioral problems should pay more attention to the mediating or regulating roles of parents’ own emotional status and parenting styles.

The current study also showed that boys scored higher on overall problems than girls. Boys’ problems were characterized by syndromes like obsessive–compulsive disorder, schizoid personality disorder, and poor interpersonal communication, whereas girls were more likely to experience emotional problems such as depression. Thus, emotional/behavioral problems manifest differently in boys and girls, and the effect of parental empathy on children of different genders (and the mechanisms of action of these effects) may differ. Studies with larger sample sizes are warranted to further explore the roles of empathy and emotional regulation in the occurrence of emotional/behavioral problems in children and adolescents of different genders and ages.

This study had some limitations. First, we did not stratify children according to age and gender owing to the relatively small sample size. Additionally, we did not elucidate the differential impact of paternal and maternal empathy and emotional regulation on the emotional/behavioral problems of children of different genders. Second, children’s emotional/behavioral problems were assessed by their parents. Owing to factors such as social desirability, parents may not have accurately reported their children’s behavioral performance. Future studies should use a combination of face‐to‐face interviews and questionnaires to obtain a more objective and comprehensive understanding of the emotional/behavioral problems of children from the perspectives of their teachers and peers.

To summarize, this study demonstrated an effect of parental cognitive empathy on childhood social competence and emotional/behavioral problems. Curriculum programs and interventions focusing on the enhancement of parental empathy should be a priority in future attempts to prevent and manage childhood emotional and behavioral problems.

Funding source

Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2017LC023), the Humanities and Social Science Research Project, Ministry of Education, China (19YJA190006), the Postgraduate Tutor Guidance Ability Improvement Project of Shandong Province (SDYY18148) and Weifang Medical University Overseas Visiting Scholar Grants Program (2017).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

Meng K, Yuan Y, Wang Y, et al. Effects of parental empathy and emotion regulation on social competence and emotional/behavioral problems of school‐age children. Pediatr Invest. 2020;4:91–98. 10.1002/ped4.12197

References

REFERENCES

- 1. Janus M, Goldberg S. Sibling empathy and behavioural adjustment of children with chronic illness. Child Care Health Dev. 1995;21:321–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Xin R, Tang H, Zhang Z, Cai X, Cheng Z, Yu Q, et al. A survey on behaviour problems in 24,013 urban children in 26 schools in 22 provinces and municipalities of China: Investigation, prevention and treatment of mental health problems of the only child and the standardization of Achenbach Child Behaviour Checklist in China. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 1992;4:47–55. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frick PJ. Early identification and treatment of antisocial behavior. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63:861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Giannotta F, Rydell AM. The prospective links between hyperactive/impulsive, inattentive, and oppositional‐defiant behaviors in childhood and antisocial behavior in adolescence: The moderating influence of gender and the parent‐child relationship quality. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47:857–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lahane S, Shah H, Nagarale V, Kamath R. Comparison of self‐esteem and maternal attitude between children with learning disability and unaffected siblings. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80:745–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Li L, Lin X, Hinshaw SP, Du H, Qin S, Fang X. Longitudinal associations between oppositional defiant symptoms and interpersonal relationships among Chinese children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46:1267–1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Najaka SS, Gottfredson DC, Wilson DB. A meta‐analytic inquiry into the relationship between selected risk factors and problem behavior. Prev Sci. 2001;2:257–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langeveld J, Gundersen K, Svartdal F. Social competence as a mediating factor in reduction of behavioral problems. Scand J Educ Res. 2012;56:381–399. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korelitz K, Garber J. Congruence of parents’ and children’s perceptions of parenting: A meta‐analysis. J Youth Adolesc. 2016;45:1973–1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mannarini S, Balottin L, Palmieri A, Carotenuto F. Emotion regulation and parental bonding in families of adolescents with internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duncombe ME, Havighurst SS, Holland KA, Frankling EJ. The contribution of parenting practices and parent emotion factors in children at risk for disruptive behavior disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43:715–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Z, Lin X, Liu Y, Li J, He J, Cao Y. Psychological analysis of children with oppositional defiant disorder: A view of family system. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2014;22:610–614. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunsmore JC, Booker JA, Ollendick TH. Parental emotion coaching and child emotion regulation as protective factors for children with oppositional defiant disorder. Soc Dev. 2013;22:444–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Burke JD, Pardini DA, Loeber R. Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36:679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cumberland‐Li A, Eisenberg N, Champion C, Gershoff E, Fabes RA. The relation of parental emotionality and related dispositional traits to parental expression of emotion and children’s social functioning. Motiv Emot. 2003;27:27–56. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stern JA, Borelli JL, Smiley PA. Assessing parental empathy: A role for empathy in child attachment. Attach Hum Dev. 2015;17:1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Allemand M, Steiger AE, Fend HA. Empathy development in adolescence predicts social competencies in adulthood. J Pers. 2015;83:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hein S, Röder M, Fingerle M. The role of emotion regulation in situational empathy‐related responding and prosocial behaviour in the presence of negative affect. Int J Psychol. 2018;53:477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crocetti E, Moscatelli S, Van der Graaff J, Keijsers L, van Lier P, Koot HM, et al. The dynamic interplay among maternal empathy, quality of mother‐adolescent relationship, and adolescent antisocial behaviors: New insights from a six‐wave longitudinal multi‐informant study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blair RJ. Responding to the emotions of others: Dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious Cog. 2005;14:698–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walter H. Social cognitive neuroscience of empathy: Concepts, circuits, and genes. Emot Rev. 2012;4:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta‐emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary data. J Fam Psychol. 1996;10:243–268. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Meta‐Emotion: How Families Communicate Emotionally. New York: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Achenback TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Schoolage Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural Supplement to the Manual for the ASEBA School‐Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well‐being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:348–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang L, Liu H, Li Z, Du W. Reliability and validity of emotion regulation questionnaire Chinese revised version. China J Health Psychol. 2007;15:503–505. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reniers RL, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane NK, Völlm BA. The QCAE: A Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. J Pers Assess. 2011;93:84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liang YS, Yang HX, Ma YT, Lui SSY, Cheung EFC, Wang Y, et al. Validation and extension of the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy in the Chinese setting. Psych J. 2019;8:439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regress ion‐Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson NM, Uusberg A, Gross JJ, Chakrabarti B. Empathy and emotion regulation: An integrative account. Prog Brain Res. 2019;247:273–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Maloney EA, Ramirez G, Gunderson EA, Levine SC, Beilock SL. Intergenerational effects of parents’ math anxiety on Children’s math schievement and anxiety. Psychol Sci. 2015;26:1480–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jellesma F. Childhood somatic complaints: Relationships with child emotional functioning and parental factors. J Behav Ther Ment Health. 2016;1:14–26. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jacobs RH, Talati A, Wickramaratne P, Warner V. The influence of paternal and maternal major depressive disorder on offspring psychiatric disorders. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24:2345–2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bushman BJ, Baumeister RF, Phillips CM. Do people aggress to improve their mood? Catharsis beliefs, affect regulation opportunity, and aggressive responding. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2001;81:17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26:41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Burke JD, Loeber R, Mutchka JS, Lahey BB. A question for DSM‐V: Which better predicts persistent conduct disorder‐delinquent acts or conduct symptoms? Crim Behav Ment Health. 2002;12:37–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]