Abstract

In clinical research, our aim is to design a study which would be able to derive a valid and meaningful scientific conclusion using appropriate statistical methods. The conclusions derived from a research study can either improve health care or result in inadvertent harm to patients. Hence, this requires a well‐designed clinical research study that rests on a strong foundation of a detailed methodology and governed by ethical clinical principles. The purpose of this review is to provide the readers an overview of the basic study designs and its applicability in clinical research.

Keywords: Clinical research study design, Clinical trials, Experimental study designs, Observational study designs, Randomization

Introduction

In clinical research, our aim is to design a study, which would be able to derive a valid and meaningful scientific conclusion using appropriate statistical methods that can be translated to the “real world” setting.1 Before choosing a study design, one must establish aims and objectives of the study, and choose an appropriate target population that is most representative of the population being studied. The conclusions derived from a research study can either improve health care or result in inadvertent harm to patients. Hence, this requires a well‐designed clinical research study that rests on a strong foundation of a detailed methodology and is governed by ethical principles.2

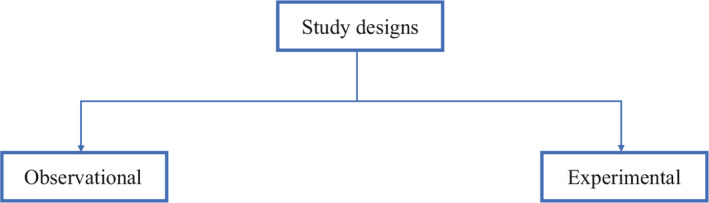

From an epidemiological standpoint, there are two major types of clinical study designs, observational and experimental.3 Observational studies are hypothesis‐generating studies, and they can be further divided into descriptive and analytic. Descriptive observational studies provide a description of the exposure and/or the outcome, and analytic observational studies provide a measurement of the association between the exposure and the outcome. Experimental studies, on the other hand, are hypothesis testing studies. It involves an intervention that tests the association between the exposure and outcome. Each study design is different, and so it would be important to choose a design that would most appropriately answer the question in mind and provide the most valuable information. We will be reviewing each study design in detail (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of clinical research study designs

Observational study designs

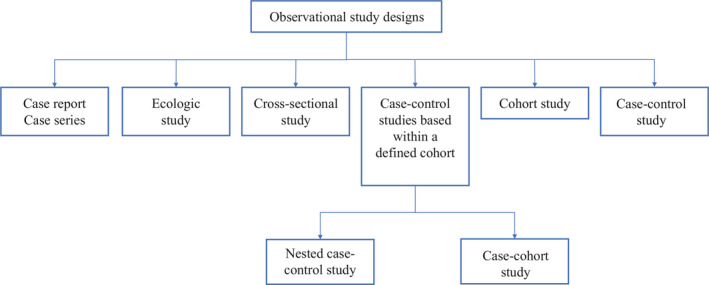

Observational studies ask the following questions: what, who, where and when. There are many study designs that fall under the umbrella of descriptive study designs, and they include, case reports, case series, ecologic study, cross‐sectional study, cohort study and case‐control study (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Classification of observational study designs

Case reports and case series

Every now and then during clinical practice, we come across a case that is atypical or ‘out of the norm’ type of clinical presentation. This atypical presentation is usually described as case reports which provides a detailed and comprehensive description of the case.4 It is one of the earliest forms of research and provides an opportunity for the investigator to describe the observations that make a case unique. There are no inferences obtained and therefore cannot be generalized to the population which is a limitation. Most often than not, a series of case reports make a case series which is an atypical presentation found in a group of patients. This in turn poses the question for a new disease entity and further queries the investigator to look into mechanistic investigative opportunities to further explore. However, in a case series, the cases are not compared to subjects without the manifestations and therefore it cannot determine which factors in the description are unique to the new disease entity.

Ecologic study

Ecological studies are observational studies that provide a description of population group characteristics. That is, it describes characteristics to all individuals within a group. For example, Prentice et al5 measured incidence of breast cancer and per capita intake of dietary fat, and found a correlation that higher per capita intake of dietary fat was associated with an increased incidence of breast cancer. But the study does not conclude specifically which subjects with breast cancer had a higher dietary intake of fat. Thus, one of the limitations with ecologic study designs is that the characteristics are attributed to the whole group and so the individual characteristics are unknown.

Cross‐sectional study

Cross‐sectional studies are study designs used to evaluate an association between an exposure and outcome at the same time. It can be classified under either descriptive or analytic, and therefore depends on the question being answered by the investigator. Since, cross‐sectional studies are designed to collect information at the same point of time, this provides an opportunity to measure prevalence of the exposure or the outcome. For example, a cross‐sectional study design was adopted to estimate the global need for palliative care for children based on representative sample of countries from all regions of the world and all World Bank income groups.6 The limitation of cross‐sectional study design is that temporal association cannot be established as the information is collected at the same point of time. If a study involves a questionnaire, then the investigator can ask questions to onset of symptoms or risk factors in relation to onset of disease. This would help in obtaining a temporal sequence between the exposure and outcome.7

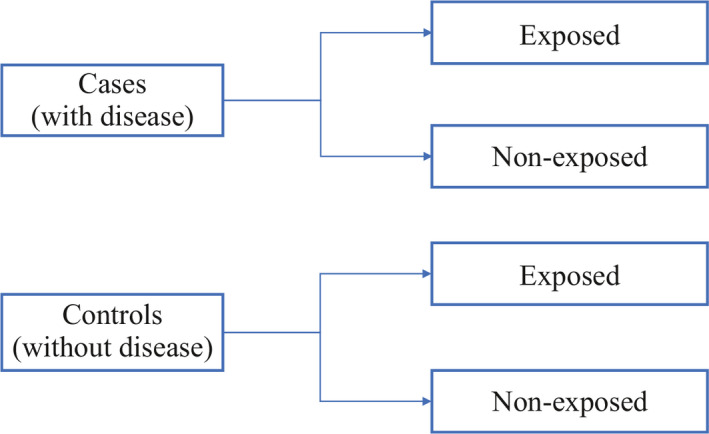

Case‐control study

Case‐control studies are study designs that compare two groups, such as the subjects with disease (cases) to the subjects without disease (controls), and to look for differences in risk factors.8 This study is used to study risk factors or etiologies for a disease, especially if the disease is rare. Thus, case‐control studies can also be hypothesis testing studies and therefore can suggest a causal relationship but cannot prove. It is less expensive and less time‐consuming than cohort studies (described in section “Cohort study”). An example of a case‐control study was performed in Pakistan evaluating the risk factors for neonatal tetanus. They retrospectively reviewed a defined cohort for cases with and without neonatal tetanus.9 They found a strong association of the application of ghee (clarified butter) as a risk factor for neonatal tetanus. Although this suggests a causal relationship, cause cannot be proven by this methodology (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Case‐control study design

One of the limitations of case‐control studies is that they cannot estimate prevalence of a disease accurately as a proportion of cases and controls are studied at a time. Case‐control studies are also prone to biases such as recall bias, as the subjects are providing information based on their memory. Hence, the subjects with disease are likely to remember the presence of risk factors compared to the subjects without disease.

One of the aspects that is often overlooked is the selection of cases and controls. It is important to select the cases and controls appropriately to obtain a meaningful and scientifically sound conclusion and this can be achieved by implementing matching. Matching is defined by Gordis et al as ‘the process of selecting the controls so that they are similar to the cases in certain characteristics such as age, race, sex, socioeconomic status and occupation’7 This would help identify risk factors or probable etiologies that are not due to differences between the cases and controls.

Cohort study

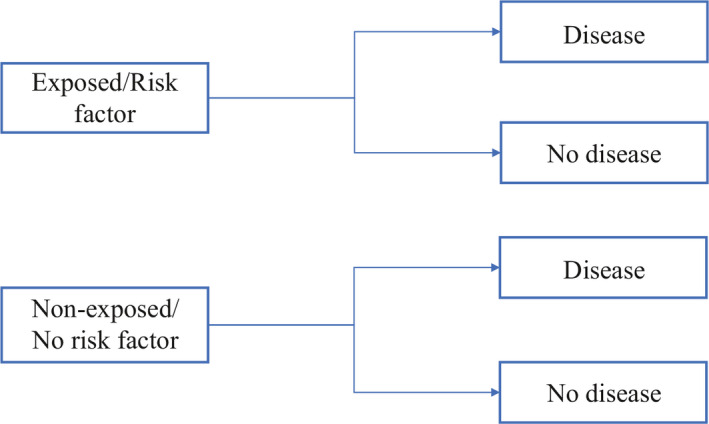

Cohort studies are study designs that compare two groups, such as the subjects with exposure/risk factor to the subjects without exposure/risk factor, for differences in incidence of outcome/disease. Most often, cohort study designs are used to study outcome(s) from a single exposure/risk factor. Thus, cohort studies can also be hypothesis testing studies and can infer and interpret a causal relationship between an exposure and a proposed outcome, but cannot establish it (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cohort study design

Cohort studies can be classified as prospective and retrospective.7 Prospective cohort studies follow subjects from presence of risk factors/exposure to development of disease/outcome. This could take up to years before development of disease/outcome, and therefore is time consuming and expensive. On the other hand, retrospective cohort studies identify a population with and without the risk factor/exposure based on past records and then assess if they had developed the disease/outcome at the time of study. Thus, the study design for prospective and retrospective cohort studies are similar as we are comparing populations with and without exposure/risk factor to development of outcome/disease.

Cohort studies are typically chosen as a study design when the suspected exposure is known and rare, and the incidence of disease/outcome in the exposure group is suspected to be high. The choice between prospective and retrospective cohort study design would depend on the accuracy and reliability of the past records regarding the exposure/risk factor.

Some of the biases observed with cohort studies include selection bias and information bias. Some individuals who have the exposure may refuse to participate in the study or would be lost to follow‐up, and in those instances, it becomes difficult to interpret the association between an exposure and outcome. Also, if the information is inaccurate when past records are used to evaluate for exposure status, then again, the association between the exposure and outcome becomes difficult to interpret.

Case‐control studies based within a defined cohort

Case‐control studies based within a defined cohort is a form of study design that combines some of the features of a cohort study design and a case‐control study design. When a defined cohort is embedded in a case‐control study design, all the baseline information collected before the onset of disease like interviews, surveys, blood or urine specimens, then the cohort is followed onset of disease. One of the advantages of following the above design is that it eliminates recall bias as the information regarding risk factors is collected before onset of disease. Case‐control studies based within a defined cohort can be further classified into two types: Nested case‐control study and Case‐cohort study.

Nested case‐control study

A nested case‐control study consists of defining a cohort with suspected risk factors and assigning a control within a cohort to the subject who develops the disease.10 Over a period, cases and controls are identified and followed as per the investigator's protocol. Hence, the case and control are matched on calendar time and length of follow‐up. When this study design is implemented, it is possible for the control that was selected early in the study to develop the disease and become a case in the latter part of the study.

Case‐cohort Study

A case‐cohort study is similar to a nested case‐control study except that there is a defined sub‐cohort which forms the groups of individuals without the disease (control), and the cases are not matched on calendar time or length of follow‐up with the control.11 With these modifications, it is possible to compare different disease groups with the same sub‐cohort group of controls and eliminates matching between the case and control. However, these differences will need to be accounted during analysis of results.

Experimental study design

The basic concept of experimental study design is to study the effect of an intervention. In this study design, the risk factor/exposure of interest/treatment is controlled by the investigator. Therefore, these are hypothesis testing studies and can provide the most convincing demonstration of evidence for causality. As a result, the design of the study requires meticulous planning and resources to provide an accurate result.

The experimental study design can be classified into 2 groups, that is, controlled (with comparison) and uncontrolled (without comparison).1 In the group without controls, the outcome is directly attributed to the treatment received in one group. This fails to prove if the outcome was truly due to the intervention implemented or due to chance. This can be avoided if a controlled study design is chosen which includes a group that does not receive the intervention (control group) and a group that receives the intervention (intervention/experiment group), and therefore provide a more accurate and valid conclusion.

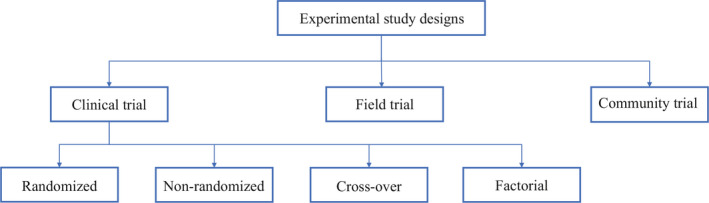

Experimental study designs can be divided into 3 broad categories: clinical trial, community trial, field trial. The specifics of each study design are explained below (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Experimental study designs

Clinical trial

Clinical trials are also known as therapeutic trials, which involve subjects with disease and are placed in different treatment groups. It is considered a gold standard approach for epidemiological research. One of the earliest clinical trial studies was performed by James Lind et al in 1747 on sailors with scurvy.12 Lind divided twelve scorbutic sailors into six groups of two. Each group received the same diet, in addition to a quart of cider (group 1), twenty‐five drops of elixir of vitriol which is sulfuric acid (group 2), two spoonfuls of vinegar (group 3), half a pint of seawater (group 4), two oranges and one lemon (group 5), and a spicy paste plus a drink of barley water (group 6). The group who ate two oranges and one lemon had shown the most sudden and visible clinical effects and were taken back at the end of 6 days as being fit for duty. During Lind's time, this was not accepted but was shown to have similar results when repeated 47 years later in an entire fleet of ships. Based on the above results, in 1795 lemon juice was made a required part of the diet of sailors. Thus, clinical trials can be used to evaluate new therapies, such as new drug or new indication, new drug combination, new surgical procedure or device, new dosing schedule or mode of administration, or a new prevention therapy.

While designing a clinical trial, it is important to select the population that is best representative of the general population. Therefore, the results obtained from the study can be generalized to the population from which the sample population was selected. It is also as important to select appropriate endpoints while designing a trial. Endpoints need to be well‐defined, reproducible, clinically relevant and achievable. The types of endpoints include continuous, ordinal, rates and time‐to‐event, and it is typically classified as primary, secondary or tertiary.2 An ideal endpoint is a purely clinical outcome, for example, cure/survival, and thus, the clinical trials will become very long and expensive trials. Therefore, surrogate endpoints are used that are biologically related to the ideal endpoint. Surrogate endpoints need to be reproducible, easily measured, related to the clinical outcome, affected by treatment and occurring earlier than clinical outcome.2

Clinical trials are further divided into randomized clinical trial, non‐randomized clinical trial, cross‐over clinical trial and factorial clinical trial.

Randomized clinical trial

A randomized clinical trial is also known as parallel group randomized trials or randomized controlled trials. Randomized clinical trials involve randomizing subjects with similar characteristics to two groups (or multiple groups): the group that receives the intervention/experimental therapy and the other group that received the placebo (or standard of care).13 This is typically performed by using a computer software, manually or by other methods. Hence, we can measure the outcomes and efficacy of the intervention/experimental therapy being studied without bias as subjects have been randomized to their respective groups with similar baseline characteristics. This type of study design is considered gold standard for epidemiological research. However, this study design is generally not applicable to rare and serious disease process as it would unethical to treat that group with a placebo. Please see section “Randomization” for detailed explanation regarding randomization and placebo.

Non‐randomized clinical trial

A non‐randomized clinical trial involves an approach to selecting controls without randomization. With this type of study design a pattern is usually adopted, such as, selection of subjects and controls on certain days of the week. Depending on the approach adopted, the selection of subjects becomes predictable and therefore, there is bias with regards to selection of subjects and controls that would question the validity of the results obtained.

Historically controlled studies can be considered as a subtype of non‐randomized clinical trial. In this study design subtype, the source of controls is usually adopted from the past, such as from medical records and published literature.1 The advantages of this study design include being cost‐effective, time saving and easily accessible. However, since this design depends on already collected data from different sources, the information obtained may not be accurate, reliable, lack uniformity and/or completeness as well. Though historically controlled studies maybe easier to conduct, the disadvantages will need to be taken into account while designing a study.

Cross‐over clinical trial

In cross‐over clinical trial study design, there are two groups who undergoes the same intervention/experiment at different time periods of the study. That is, each group serves as a control while the other group is undergoing the intervention/experiment.14 Depending on the intervention/experiment, a ‘washout’ period is recommended. This would help eliminate residuals effects of the intervention/experiment when the experiment group transitions to be the control group. Hence, the outcomes of the intervention/experiment will need to be reversible as this type of study design would not be possible if the subject is undergoing a surgical procedure.

Factorial trial

A factorial trial study design is adopted when the researcher wishes to test two different drugs with independent effects on the same population. Typically, the population is divided into 4 groups, the first with drug A, the second with drug B, the third with drug A and B, and the fourth with neither drug A nor drug B. The outcomes for drug A are compared to those on drug A, drug A and B and to those who were on drug B and neither drug A nor drug B.15 The advantages of this study design that it saves time and helps to study two different drugs on the same study population at the same time. However, this study design would not be applicable if either of the drugs or interventions overlaps with each other on modes of action or effects, as the results obtained would not attribute to a particular drug or intervention.

Community trial

Community trials are also known as cluster‐randomized trials, involve groups of individuals with and without disease who are assigned to different intervention/experiment groups. Hence, groups of individuals from a certain area, such as a town or city, or a certain group such as school or college, will undergo the same intervention/experiment.16 Hence, the results will be obtained at a larger scale; however, will not be able to account for inter‐individual and intra‐individual variability.

Field trial

Field trials are also known as preventive or prophylactic trials, and the subjects without the disease are placed in different preventive intervention groups.16 One of the hypothetical examples for a field trial would be to randomly assign to groups of a healthy population and to provide an intervention to a group such as a vitamin and following through to measure certain outcomes. Hence, the subjects are monitored over a period of time for occurrence of a particular disease process.

Overview of methodologies used within a study design

Randomization

Randomization is a well‐established methodology adopted in research to prevent bias due to subject selection, which may impact the result of the intervention/experiment being studied. It is one of the fundamental principles of an experimental study designs and ensures scientific validity. It provides a way to avoid predicting which subjects are assigned to a certain group and therefore, prevent bias on the final results due to subject selection. This also ensures comparability between groups as most baseline characteristics are similar prior to randomization and therefore helps to interpret the results regarding the intervention/experiment group without bias.

There are various ways to randomize and it can be as simple as a ‘flip of a coin’ to use computer software and statistical methods. To better describe randomization, there are three types of randomization: simple randomization, block randomization and stratified randomization.

Simple randomization

In simple randomization, the subjects are randomly allocated to experiment/intervention groups based on a constant probability. That is, if there are two groups A and B, the subject has a 0.5 probability of being allocated to either group. This can be performed in multiple ways, and one of which being as simple as a ‘flip of a coin’ to using random tables or numbers.17 The advantage of using this methodology is that it eliminates selection bias. However, the disadvantage with this methodology is that an imbalance in the number allocated to each group as well as the prognostic factors between groups. Hence, it is more challenging in studies with a small sample size.

Block randomization

In block randomization, the subjects of similar characteristics are classified into blocks. The aim of block randomization is to balance the number of subjects allocated to each experiment/intervention group. For example, let's assume that there are four subjects in each block, and two of the four subjects in each block will be randomly allotted to each group. Therefore, there will be two subjects in one group and two subjects in the other group.17 The disadvantage with this methodology is that there is still a component of predictability in the selection of subjects and the randomization of prognostic factors is not performed. However, it helps to control the balance between the experiment/intervention groups.

Stratified randomization

In stratified randomization, the subjects are defined based on certain strata, which are covariates.18 For example, prognostic factors like age can be considered as a covariate, and then the specified population can be randomized within each age group related to an experiment/intervention group. The advantage with this methodology is that it enables comparability between experiment/intervention groups and thus makes result analysis more efficient. But, with this methodology the covariates will need to be measured and determined before the randomization process. The sample size will help determine the number of strata that would need to be chosen for a study.

Blinding

Blinding is a methodology adopted in a study design to intentionally not provide information related to the allocation of the groups to the subject participants, investigators and/or data analysts.19 The purpose of blinding is to decrease influence associated with the knowledge of being in a particular group on the study result. There are 3 forms of blinding: single‐blinded, double‐blinded and triple‐blinded.1 In single‐blinded studies, otherwise called as open‐label studies, the subject participants are not revealed which group that they have been allocated to. However, the investigator and data analyst will be aware of the allocation of the groups. In double‐blinded studies, both the study participants and the investigator will be unaware of the group to which they were allocated to. Double‐blinded studies are typically used in clinical trials to test the safety and efficacy of the drugs. In triple‐blinded studies, the subject participants, investigators and data analysts will not be aware of the group allocation. Thus, triple‐blinded studies are more difficult and expensive to design but the results obtained will exclude confounding effects from knowledge of group allocation.

Blinding is especially important in studies where subjective response are considered as outcomes. This is because certain responses can be modified based on the knowledge of the experiment group that they are in. For example, a group allocated in the non‐intervention group may not feel better as they are not getting the treatment, or an investigator may pay more attention to the group receiving treatment, and thereby potentially affecting the final results. However, certain treatments cannot be blinded such as surgeries or if the treatment group requires an assessment of the effect of intervention such as quitting smoking.

Placebo

Placebo is defined in the Merriam‐Webster dictionary as ‘an inert or innocuous substance used especially in controlled experiments testing the efficacy of another substance (such as drug)’.20 A placebo is typically used in a clinical research study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a drug/intervention. This is especially useful if the outcome measured is subjective. In clinical drug trials, a placebo is typically a drug that resembles the drug to be tested in certain characteristics such as color, size, shape and taste, but without the active substance. This helps to measure effects of just taking the drug, such as pain relief, compared to the drug with the active substance. If the effect is positive, for example, improvement in mood/pain, then it is called placebo effect. If the effect is negative, for example, worsening of mood/pain, then it is called nocebo effect.21

The ethics of placebo‐controlled studies is complex and remains a debate in the medical research community. According to the Declaration of Helsinki on the use of placebo released in October 2013, “The benefits, risks, burdens and effectiveness of a new intervention must be tested against those of the best proven intervention(s), except in the following circumstances:

Where no proven intervention exists, the use of placebo, or no intervention, is acceptable; or

Where for compelling and scientifically sound methodological reasons the use of any intervention less effective than the best proven one, the use of placebo, or no intervention is necessary to determine the efficacy or safety of an intervention and the patients who receive any intervention less effective than the best proven one, placebo, or no intervention will not be subject to additional risks of serious or irreversible harm as a result of not receiving the best proven intervention.

Extreme care must be taken to avoid abuse of this option”.22

Hence, while designing a research study, both the scientific validity and ethical aspects of the study will need to be thoroughly evaluated.

Bias

Bias has been defined as “any systematic error in the design, conduct or analysis of a study that results in a mistaken estimate of an exposure's effect on the risk of disease”.23 There are multiple types of biases and so, in this review we will focus on the following types: selection bias, information bias and observer bias. Selection bias is when a systematic error is committed while selecting subjects for the study. Selection bias will affect the external validity of the study if the study subjects are not representative of the population being studied and therefore, the results of the study will not be generalizable. Selection bias will affect the internal validity of the study if the selection of study subjects in each group is influenced by certain factors, such as, based on the treatment of the group assigned. One of the ways to decrease selection bias is to select the study population that would representative of the population being studied, or to randomize (discussed in section “Randomization”).

Information bias is when a systematic error is committed while obtaining data from the study subjects. This can be in the form of recall bias when subject is required to remember certain events from the past. Typically, subjects with the disease tend to remember certain events compared to subjects without the disease. Observer bias is a systematic error when the study investigator is influenced by the certain characteristics of the group, that is, an investigator may pay closer attention to the group receiving the treatment versus the group not receiving the treatment. This may influence the results of the study. One of the ways to decrease observer bias is to use blinding (discussed in section “Blinding”).

Thus, while designing a study it is important to take measure to limit bias as much as possible so that the scientific validity of the study results is preserved to its maximum.

Overview of drug development in the United States of America

Now that we have reviewed the various clinical designs, clinical trials form a major part in development of a drug. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) plays an important role in getting a drug approved for clinical use. It includes a robust process that involves four different phases before a drug can be made available to the public. Phase I is conducted to determine a safe dose. The study subjects consist of normal volunteers and/or subjects with disease of interest, and the sample size is typically small and not more than 30 subjects. The primary endpoint consists of toxicity and adverse events. Phase II is conducted to evaluate of safety of dose selected in Phase I, to collect preliminary information on efficacy and to determine factors to plan a randomized controlled trial. The study subjects consist of subjects with disease of interest and the sample size is also small but more that Phase I (40–100 subjects). The primary endpoint is the measure of response. Phase III is conducted as a definitive trial to prove efficacy and establish safety of a drug. Phase III studies are randomized controlled trials and depending on the drug being studied, it can be placebo‐controlled, equivalence, superiority or non‐inferiority trials. The study subjects consist of subjects with disease of interest, and the sample size is typically large but no larger than 300 to 3000. Phase IV is performed after a drug is approved by the FDA and it is also called the post‐marketing clinical trial. This phase is conducted to evaluate new indications, to determine safety and efficacy in long‐term follow‐up and new dosing regimens. This phase helps to detect rare adverse events that would not be picked up during phase III studies and decrease in the delay in the release of the drug in the market. Hence, this phase depends heavily on voluntary reporting of side effects and/or adverse events by physicians, non‐physicians or drug companies.2

Conclusion

We have discussed various clinical research study designs in this comprehensive review. Though there are various designs available, one must consider various ethical aspects of the study. Hence, each study will require thorough review of the protocol by the institutional review board before approval and implementation.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Chidambaram AG, Josephson M. Clinical research study designs: The essentials. Pediatr Invest. 2019;3:245‐252. 10.1002/ped4.12166

REFERENCES

- 1. Lim HJ, Hoffmann RG. Study design: The basics. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;404:1‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Umscheid CA, Margolis DJ, Grossman CE. Key concepts of clinical trials: A narrative review. Postgrad Med. 2011;123:194‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grimes DA, Schulz KF. An overview of clinical research: The lay of the land. Lancet. 2002;359:57‐61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wright SM, Kouroukis C. Capturing zebras: What to do with a reportable case. CMAJ. 2000;163:429‐431. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Prentice RL, Kakar F, Hursting S, Sheppard L, Klein R, Kushi LH. Aspects of the rationale for the women's health trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:802‐814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Connor SR, Downing J, Marston J. Estimating the global need for palliative care for children: A cross‐sectional analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53:171‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Celentano DD, Szklo M. Gordis epidemiology. 6th ed Elsevier, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement : Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg. 2011;9:672‐677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Traverso HP, Bennett JV, Kahn AJ, Agha SB, Rahim H, Kamil S, et al. Ghee applications to the umbilical cord: A risk factor for neonatal tetanus. Lancet. 1989;1:486‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ernster VL. Nested case‐control studies. Prev Med. 1994;23:587‐590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of case‐cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1165‐1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lind J. Nutrition classics. A treatise of the scurvy by james lind, MDCCLIII. Nutr Rev. 1983;41:155‐157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dennison DK. Components of a randomized clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 1997;32:430‐438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sibbald B, Roberts C. Understanding controlled trials. Crossover trials. BMJ. 1998;316:1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cipriani A, Barbui C. What is a factorial trial? Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2013;22:213‐215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Margetts BM, Nelson M. Design concepts in nutritional epidemiology. 2nd ed Oxford University Press; 1997:415‐417. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Altman DG, Bland JM. How to randomise. BMJ. 1999;319:703‐704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Suresh K. An overview of randomization techniques: An unbiased assessment of outcome in clinical research. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2011;4:8‐11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19. Karanicolas PJ, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M. Practical tips for surgical research: Blinding: Who, what, when, why, how? Can J Surg. 2010;53:345‐348. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Placebo. Merriam‐Webster Dictionary. Accessed 10/28/2019.

- 21. Pozgain I, Pozgain Z, Degmecic D. Placebo and nocebo effect: A mini‐review. Psychiatr Danub. 2014;26:100‐107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Medical Association . World medical association declaration of helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191‐2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schlesselman JJ. Case‐control studies: Design, conduct, and analysis. United States of America: New York: Oxford University Press; 1982:124‐143. [Google Scholar]