Abstract

The first total synthesis of asperphenins A and B has been accomplished in concise, highly stereoselective fashion from commercially available materials (15 steps, 9.7% and 14.2% overall yields, respectively). The convergent route featured the judicious choice of protecting groups, fragment assembly strategy and a late-stage iron-catalyzed Wacker-type selective oxidation of an internal alkene to the corresponding ketone.

Graphical Abstract

Metabolites isolated from marine fungus often possess unique structural features and incorporate new or unusual assemblages of functional groups. Many of them provide novel lead molecules for probing fundamental biological processes and the development of novel chemotherapeutic agents that target cancers. Our laboratory is engaged in a program devoted to the total synthesis and evaluation of marine natural products.[1] Herein, we disclose the first total synthesis of asperphenins A and B by utilizing a highly efficient and convergent approach.

Asperphenins A and B (Scheme 1) were isolated from a culture broth of marine-derived Aspergillus sp. collected from the shore of Jeju Island, Korea.[2] The relative and absolute stereochemical configuration of asperphenins had been established by a combination of spectroscopic analyses, chemical degradation, Mosher ester analysis, CD measurements and ECD calculations. Structurally, these two natural products are comprised of a β-hydroxy fatty acid, a tripeptide and a trihydroxybenzophenone. Asperphenins A and B exhibit significant cytotoxicity against several human cancer cell lines, e.g. with IC50 values of 0.8 and 1.1 μM respectively against RKO colorectal carcinoma cells.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis of Asperphenin A

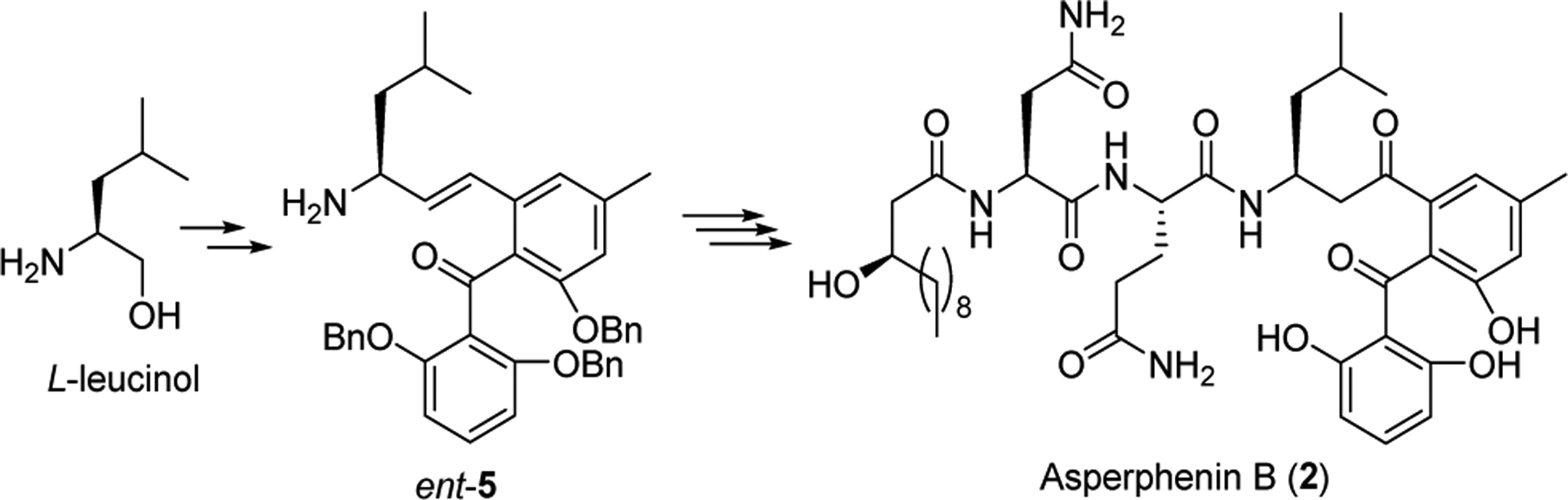

Scheme 1 outlines our retrosynthetic analysis plan. We anticipated that the condensation of acid 3 with either fragment 4 or 5 followed by removal of protecting groups would give rise to the natural products. We envisioned the amine moiety of 4 or 5 could arise from either asymmetric Mannich reaction of ketone 6a or a stereoselective Wittig olefination of aldehyde 6b with a leucinol-derived triphenylphosphonium salt. Both 6a and 6b, in turn, could be accessed from a reaction of aryl iodide 8 with lactols 7a and 7b, respectively.

The synthesis of fragment 3 commenced with the known compound 9,[3] which underwent titanium tetrachloride mediated enatioselective aldol reaction with caprinaldehyde to provide 10[4] as a single diastereomer in 81% yield (Scheme 2). Protection of the resulting alcohol as its TBS ether followed by hydrolytic cleavage of the chiral auxiliary furnished the acid 11 in 76% yield. In parallel, coupling of N-Cbz-L-asparagine and L-glutamine methyl ester under the influence of HATU in the presence of HOAt and DIPEA furnished the corresponding dipeptide, which was subjected to hydrogenolysis of the Cbz protecting group to produce amine 14 in 76% yield over two steps. A second HATU/HOAt-mediated condensation of acid 11 and amine 14 provided the corresponding amide 15 in 85% yield. Saponification of the methyl ester with LiOH in aqueous methanol followed by acidification afforded the acid 3 in 81% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Fragment 3

Our planned first approach to asperphenin A required the synthesis of fragment 4 from ketone 6a via an asymmetric Mannich reaction (Scheme 3). Thus, 2-methoxy-4-methylbenzoic acid 16 was converted into the corresponding acid chloride and then coupled with N, N-diethyl amine to afford 17 in 95% yield. Regioselective formylation of 17 to aldehyde 18 was achieved through an amide-directed ortho-lithiation (tert-BuLi, TMEDA) followed by quenching with DMF (86% yield).[5] Addition of methylmagnesium bromide to aldehyde 18 afforded the corresponding secondary alcohol, which was immediately subjected to acid-promoted lactonization to give rise to 19 in 92% yield over 2 steps.[5b, 6] Lactone 19 was treated with boron tribromide in dichloromethane to produce the crude deprotected phenol, which was then re-protected by benzylation using benzyl bromide and potassium carbonate to afford the benzyl derivative 20 in 81% yield. Partial reduction of the lactone 19 using DIBAL-H at −78 °C furnished the corresponding lactol 7a as a latent hydroxyaldehyde in 95% yield. Spurred by Knochel’s seminal findings on halogen-magnesium exchange,[7] we opted to convert the readily available aryl iodide 8 to the corresponding arylmetal species with i-PrMgCl·LiCl, followed by the addition of lactol 7a to give rise to biphenyl diol 21 as a mixture of diastereomers in 85% yield. Ley’s TPAP oxidation[8] of 21 delivered the corresponding diketone 6a in 78% yield and set the stage for the exploration of the key asymmetric Mannich reaction.[9] However, this reaction proved to be challenging due to the high propensity of trapping of the transient enolate intramolecularly with an electrophile. Accordingly, treatment of methyl ketone 6a and tert-butanesulfinyl imine 22 with various bases, solvent, and concentrations at low temperature, resulted in no observation of the desired product. For example, while exposure of both 6a and 22 in the presence of one equivalent of potassium hexamethyldisilazane (KHMDS), two aldol products (23 and 24) were obtained (Scheme 3). Given that the reactions afforded β-amino ketone 23 as the major product, we reasoned that the asymmetric Mannich reaction occurred with simultaneous cyclization of the regenerated enolate onto the ketone to afford the thermodynamically more stable product.

Scheme 3.

Attempts on the Synthesis of Intermediate 4

To circumvent the problems encountered in above strategy toward the construction of chiral amine 4 via an asymmetric Mannich reaction, we turned our attention to the strategy where the ketone moiety would have to be installed at a later stage of the synthesis. Thus, aldehyde 18 was transformed into lactone 25 by a two-step sequence involving (1) reduction with sodium borohydride and (2) acid-promoted lactonization (Scheme 4). Lactone 25 was then elaborated to the lactol 7b in 81% yield by an identical strategy as described for 7a, including methyl ether deprotection and reprotection of the resulting free phenol with benzyl bromide and potassium carbonate, followed by partial reduction of the lactone with DIBAL-H at −78 °C. Again, the Grignard reagent derived from aryl iodide 8 added to lactol 7b provided biphenyl diol 27 in 72% yield. To our surprise, use of the previously employed Ley’s TPAP oxidation of diol 27 led to the dicarbonyl product 6b in 27% yield along with the over-oxidation product 28 (58%). Similar results were obtained with manganese dioxide[11] in dichlorometane. 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone (DDQ)[12] oxidation of the benzylic alcohols in 27 provided intractable mixtures with nodesired products. Gratifyingly, treatment of diol 27 with PCC on alumina[13] in DCM smoothly afforded the desired aldehyde 6b in 76% yield as the sole product.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of Aldehyde 6b

In parallel, D-leucinol (29) was transformed into trifluoroacetamide 30 by a three-step sequence involving (1) trifluoroacetylation of the primary amine; (2) conversion of the alcohol into the bromide with CBr4 and Ph3P; (3) the β-Amino phosphonium salt formation upon treating the resulting bromide with triphenyl phosphine in refluxing toluene. Wittig reaction of aldehyde 6b with the phosphorane derived from phosphonium bromide 30 was next examined. Thus, treatment of the phosphonium salt 30 with 2.1 equivalent of n-butyl lithium followed by addition of the aldehyde 6b delivered the alkene 31 enriched in the desired E-isomer (E/Z = 5:1).[14] The desired product 31 could be isolated free of the Z isomer in 77% yield by chromatography on silica gel. The presence of the trifluoroacetamide in 30 ensured the generation of the dianion intermediate, which presumably played a critical role to the stereochemical outcome of this transformation.[14b, 15] Hydrolysis of the trifluoroacetamide 31 gave allylic amine 5 in nearly quantitative yield. Acetylation of amine 5 was achieved under basic conditions with acetyl chloride to afford 32 in 82% yield. (Scheme 5)

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of Amine 5 and Amides 31, 32

With alkenes 31 and 32 in hand, the stage was set to explore the crucial Wacker-type oxidation. Attempts to selectively oxidize the E-alkenes 31 and 32 using molecular iodine or N-iodosuccinimide[16] gave little or no desired products (Table 1, entries 1–4). The literature precedents suggested that Wacker oxidation of cinnamyl azides[17a] and 2-styryltetrahydro-2H-pyrans[17b] occurred predominantly or exclusively at the benzylic rather than the homobenzylic carbon. Attempted Wacker oxidation of both 31 and 32, however, delivered only trace quantities of the desired ketone. As we searched for alternative methods of transforming alkenes 31 and 32 into ketones 33a and 33b, we were drawn to a report by Han and co-workers of a mild variant of the Wacker-type oxidation.[18] In the Han modification of the Wacker oxidation, iron(II) chloride, polymethylhydrosiloxane and air were employed as a highly efficient and selective catalytic system. Because the mild oxidation conditions enable exceptional functional-group tolerance, we tested this protocol with alkene 31. We were pleased to discover that the iron-catalyzed Wacker-type oxidation of alkene 31 provided ketone 33a in 30% yield. To our delight, the same iron-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of 32 delivered 33b in 89% yield. (Table 1, entries 7, 8).

Table 1.

Optimization of the Wacker-type Oxidation

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | alkene | condition | toC | yield |

| 1 | 31 | I2, dioxane/H2O | 90 | N.D. |

| 2 | 32 | I2, dioxane/H2O | 90 | N.D. |

| 3 | 31 | NIS, dioxane/H2O | 30 | trace |

| 4 | 32 | NIS, dioxane/H2O | 30 | trace |

| 5 | 31 | PdCl2, CuCl, O2, H2O, DMF | 50 | trace |

| 6 | 32 | PdCl2, CuCl, O2, H2O, DMF | 50 | trace |

| 7 | 31 | FeCl2, PMHS, EtOH, air | 80 | 30% |

| 8 | 32 | FeCl2, PMHS, EtOH, air | 80 | 89% |

Encouraged by the successful transformation of alkene 32 to the corresponding β-ketone amide 33b, we proceeded with the total synthesis of asperphenin A and B as outlined in Schemes 6 and 7. Thus, coupling of acid 3 and allylic amine 5 under the influence of EDCI in the presence of HOAt and DIPEA afforded 34 in 71% yield. After removal of the TBS group to give rise to the corresponding alcohol 35, which was then subjected to an iron-catalyzed Wacker oxidation to furnish 36 in 85% yield. The final global hydrogenative debenzylation went on without incident to provide asperphenin A in 72% yield. (Scheme 6) To this end, we synthesized ent-5 following the same synthesis as for 5, but starting with L-leucinol. This was readily achieved, and ent-5 was incorporated into the synthesis as previously performed to afford asperphenin B with no adverse consequences. (Scheme 7) The spectral data for synthetic 1 and 2 (1H, 13C NMR and HMRS) were identical with those published for the natural products, and the optical rotation of our products, ([α]D25 – 22.0, c 0.1, MeOH, for asperphenin A; [α]D25 –16.2, c 0.1, MeOH, for asperphenin B), corresponded well with the literature value, (lit. [α]D25 –24.7, c 0.1, MeOH, for asperphenin A; [α]D25 –18.4, c 0.1, MeOH, for asperphenin B), leading us to conclude that synthetic 1 and 2 were of the same absolute stereochemistry as natural asperphenins A and B.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of Asperphenin A

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of Asperphenin B

With the synthetic asperphenins A (1) & B (2) in hand, the screening of cytotoxic activities toward a number of cancer cell lines has been investigated (Figure 1). The initial cytotoxicity evaluation of 1 and 2 was performed across a panel of the HIF dependent HCT116 colorectal cancer cell lines using isogenic (HCT116HIF−1α−/−HIF−2α−/− and HCT116WT KRAS) knock out cells to identify if these compounds preferentially target HIF/KRAS pathways. Both compounds were only moderately cytotoxic against parental HCT116 with reduced cytotoxicityagainst the human normal colon cells, CCD-18Co.[10] Asperphenin A (1) shows a 2-fold decrease in potency against HCT116HIF−1α−/−HIF2α−/− (IC50 shifts from 2.2 uM to 5.1 uM) with simultaneous decrease in efficacy. For cells lacking oncogenic KRAS (HCT116WT KRAS) only a slight decrease in total efficacy was observed compared to the parental HCT116 cell line.[10]Asperphenins may have a slight selectivity for colon cancer cells over normal cells that could be explored further with SAR studies.

Figure 1.

Effect of Asperphenin A (1) and B (2) on isogenic HCT116 colon cancer cells and normal colon cells.

In summary, stereocontrolled total synthesis of asperphenins A and B has been accomplished through combination of the judicious choice of protecting groups, a fragment assembly strategy and a late-stage iron-catalyzed Wacker-type selective oxidation of an internal alkene to the corresponding ketone. Both of the synthetic samples exhibit interesting results in preliminary biological assays.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We acknowledge financial support from the Shenzhen Peacock Plan (KQTD2015071714043444); the NSFC (21772009), the SZSTIC (JCYJ20160527100424909), (JCYJ20170818090017617), (JCYJ20170818090238288) and the GDNSF (2014B030301003), the National Institutes of Health, NCI grant R01CA172310, the Debbie and Sylvia DeSantis Chair professorship (H.L.) and NCI Research Specialist Award R50CA211487 (R.R)

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

Experimental details and data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Al-Awadhi FH; Gao B; Rezaei MA; Kwan JC; Li C; Ye T; Paul VJ; Luesch HJ Med. Chem 2018, 61, 6364.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guo Y; Zhao M; Xu Z; Ye T Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 3572.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhou J; Gao B; Xu Z; Ye TJ Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gunasekera SP; Li Y; Ratnayake R; Luo D; Lo J; Reibenspies JH; Xu Z; Clare-Salzler MJ; Ye T; Paul VJ; Luesch H Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 8158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Qu S; Chen Y; Wang X; Chen S; Xu Z; Ye T Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lei H; Yan J; Yu J; Liu Y; Wang Z; Xu Z; Ye T Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liao L; Bae SY; Won TH; You M; Kim S-H; Oh D-C; Lee SK; Oh K-B; Shin J Org. Lett 2017, 19, 2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kitir B; Baldry M; Ingmer H; Olsen CA Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 7721. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Yadav JS; Dachavaram SS; Grée R; Das S, Tetrahedron Lett 2015, 56, 3999. [Google Scholar]; (b) Yadav JS; Rajendar G; Ganganna B; Srihari P Tetrahedron Lett 2010, 51, 2154. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Snieckus V Chem. Rev 1990, 90, 879. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Z; Gao Y; Tang Y; Dai M; Wang G; Wang Z; Yang Z Org. Lett 2008, 10, 3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brimble MA; Flowers CL; Hutchinson JK; Robinson JE; Sidford M Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 10036. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Knochel P; Dohle W; Gommermann N; Kneisel FF; Kopp F; Korn T; Sapountzis I; Vu VA Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2003, 42, 4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krasovskiy A; Knochel P Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Krasovskiy A; Straub BF; Knochel P Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2005, 45, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saha T; Maitra R; Chattopadhyay SK Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2013, 9, 2910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Babij NR; Wolfe JP Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis FA; Yang B Org. Lett 2003, 5, 5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tang TP; Ellman JA J. Org. Chem 2002, 67, 7819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. For the details, please check the supporting Information.

- 11.(a) Hollinshead SP; Nichols JB; Wilson JW J. Org. Chem 1994, 59, 6703. [Google Scholar]; (b) Srivastava AK; Panda G Chem.- Eur. J 2008, 14, 4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Torricelli F; Bosson J; Besnard C; Chekini M; Bürgi T; Lacour J Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 1796.; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bosson J; Labrador GM; Pascal S; Miannay F-A; Yushchenko O; Li H; Bouffier L; Sojic N; Tovar RC; Muller G; Jacquemin D; Laurent AD; Guennic BL; Vauthey E; Lacour J Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 18394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan SR; Harrowven DC; Bradley M Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 5989. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Andersson IE; Dzhambazov B; Holmdahl R; Linusson A; Kihlberg JJ Med. Chem 2007, 50, 5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wiktelius D; Luthman K Org. Biomol. Chem 2007, 5, 603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maryanoff BE; Reitz AB; Duhl-Emswiler BA J. Am. Chem. Soc 1985, 107, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harikrishna K; Mukkamala R; Hinkelmann B; Sasse F; Aidhen IS Eur. J. Org. Chem 2014, 2014, 1066. [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Carlson AS; Calcanas C; Brunner RM; Topczewski JJ Org. Lett 2018, 20, 1604.; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Keinan E; Seth KK; Lamed RJ Am. Chem. Soc 1986, 108, 3474. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Liu B; Jin F; Wang T; Yuan X; Han W Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 12712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Han W; Liu B Synlett 2018, 29, 383. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.