Highlights

-

•

Pericardial effusion with acute cardiac tamponade may be a potential complication of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection.

-

•

This should be kept in mind especially when facing mechanically ventilated patients with acute hemodynamic collapse.

-

•

Bedside TTE is a valuable tool for prompt diagnosis and life-saving therapeutic pericardiocentesis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pericardial effusion, Cardiac tamponade, Shock

Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has recently evolved as a pandemic disease. Although the respiratory system is predominantly affected, cardiovascular complications have been frequently identified, including acute myocarditis, myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, arrhythmias and venous thromboembolic events. Pericardial disease has been rarely reported. We present a case of acute life-threatening cardiac tamponade caused by a small pericardial effusion in a mechanically ventilated patient with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. The patient presented acute circulatory collapse with hemodynamic features of cardiogenic or obstructive shock. Bedside echocardiography permitted prompt diagnosis and life-saving pericardiocentesis. Further investigation revealed no other apparent cause of pericardial effusion except for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cardiac tamponade may complicate COVID-19 and should be included in the differential diagnosis of acute hemodynamic deterioration in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients.

Introduction

COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 has evolved as a pandemic disease affecting predominantly the respiratory system. In Europe, 5–10 % of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 require admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) mostly because of severe hypoxemic respiratory failure [1]. Cardiovascular complications including acute myocarditis, myocardial infarction, acute heart failure with cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias and venous thromboembolic events are frequently associated with COVID-19 [2]. As many pathophysiologic and clinical aspects of this newly recognized entity are still unknown, reports of atypical presentations and unusual complications of COVID-19 are of particular interest. In this context, we report a case of acute cardiac tamponade manifesting as obstructive shock in a mechanically ventilated patient with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia.

Case report

An 89 year-old male was admitted to the ICU on April 14, 2020. The patient had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) on nocturnal oxygen therapy and no known cardiac disease. He had been hospitalized since March 30 because of COPD exacerbation. During his hospitalization his condition improved, but on April 8 he developed new-onset fever with hypoxemia and bilateral lung infiltrates. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of a nasopharyngeal swab was positive for SARS-CoV-2. He was treated with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin but was intubated on April 14 because of worsening hypoxemia.

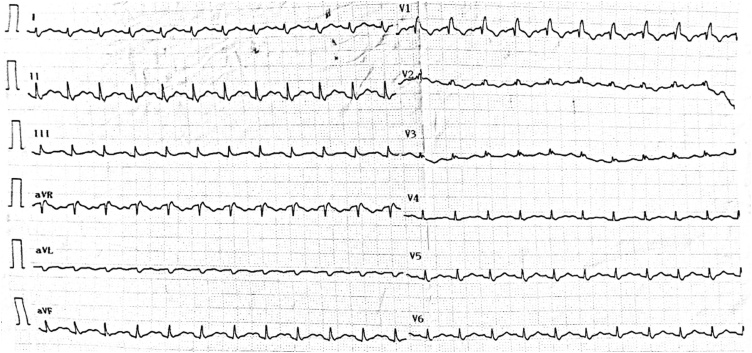

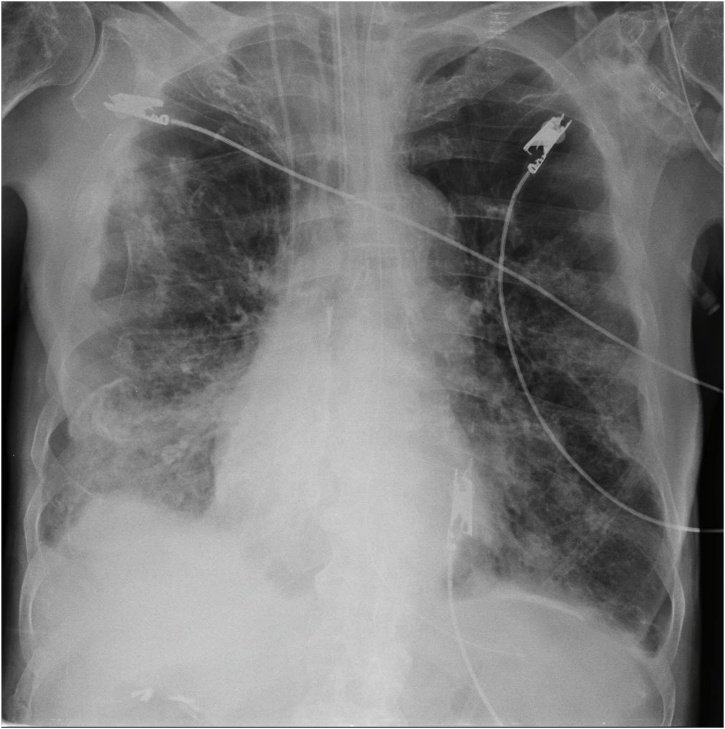

On admission, he was sedated and mechanically ventilated with a tidal volume of 6.5 ml/kg of Predicted Body Weight at a rate of 20 breaths per minute and Positive End-Expiratory Pressure (PEEP) of 8cmH2O. Physical examination was unremarkable and he was hemodynamically stable. He had a PaO2/FiO2 of 110, respiratory system compliance 35 ml/cmH2O, airway resistance 18cmH2O/L/sec and intrinsic PEEP of 2cmH2O. Central venous pressure (CVP) was 12 mmHg and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) was 76 %. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed incomplete RBBB (Fig. 1). Chest X-ray revealed signs of emphysema and bilateral infiltrates (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

ECG on admission showing incomplete RBBB.

Fig. 2.

Admission Chest X-ray with signs of emphysema and bilateral infiltrates.

Abnormal laboratory tests included mild leukocytosis with low lymphocyte count (800/μL) and elevated C-reactive protein (24.77 mg/dL; RR < 0.5 mg/dL), ferritin (2279 ng/mL; RR 11−307 ng/mL), interleukin-6 (52 pg/mL; RR <5 pg/mL) and d-dimer levels (1.65 μg/mL; RR < 0.89 μg/mL). A panel of lower respiratory specimen was negative, including influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus, corona virus, metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, rhinovirus, Legionella pneumophila, Myocoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae and bacteria. Urinary antigen testing for Legionella pneumophila and Streptococcus pneumoniae was also negative.

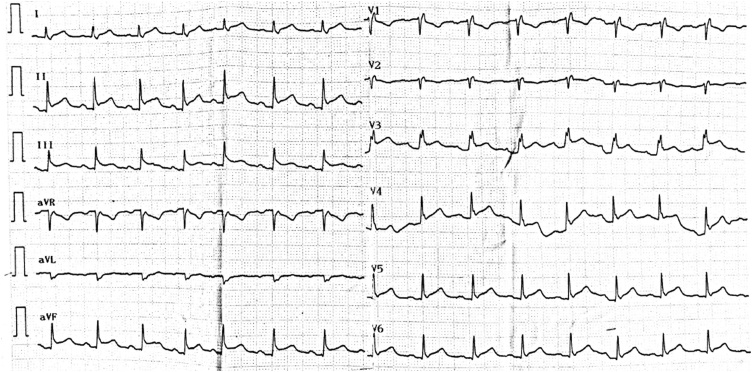

Twenty-four hours after admission the patient developed acute circulatory collapse non-responding to fluid resuscitation and high dose of vasopressors. His CVP was 18 mmHg and ScvO2 was 58 %, indicating cardiogenic or obstructive pathophysiology of shock. Differential diagnosis included myocardial infarction, acute myocarditis due to COVID-19, acute pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade. ECG showed new onset infero-lateral ST elevation (Fig. 3). High sensitive cardiac troponin I was 35 pg/mL (RR < 34 pg/mL). Bedside transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed an anterior pericardial effusion with right ventricular diastolic collapse and mitral valve inflow variation of 30 %, while left ventricular systolic function was normal with LVEF of 60 % (Video 1). Other causes of shock were excluded by TTE. Echo-guided pericardiocentesis was immediately performed and 200 mL of serous fluid were aspirated with subsequent hemodynamic improvement (Video 2). Pericardial drainage was maintained in situ for 24 h and yielded a total of 240 mL of fluid.

Fig. 3.

ECG showing infero-lateral ST elevation.

The pericardial fluid tested negative for Gram stain and acid-fast bacilli smear. No growth on bacterial and fungal cultures was reported. Molecular testing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis was negative as was RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Fluid cytology yielded no malignant cells. Thyroid function tests were normal. Serologic tests for Coxsackievirus, Echovirus, hepatitis viruses, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus and autoantibodies were also negative. Treatment with colchicine was started. Following fluid drainage the patient was rapidly weaned off vasopressors. Repeat echocardiograms showed no recurrence of pericardial effusion. However, on the sixth day he developed septic shock and multi-organ failure caused by multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumanii and died.

Discussion

Pericardial effusion has been reported in 4.55 % out of 2738 COVID-19 patients in a meta-analysis of chest computed tomography imaging findings [3]. Critically ill patients had higher incidence of pericardial effusion compared to less severely ill [4]. However, clinically significant pericardial disease is rare. To our knowledge, only three cases of cardiac tamponade have been reported so far [[5], [6], [7]]. One in a 47-year-old woman with a past history of myopericarditis, the second in a 67-year-old woman with a history of non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, and the third in a 59-year-old man six weeks after coronary artery bypass surgery. All three patients had pre-existing cardiac disease and none was on mechanical ventilation. In our case cardiac tamponade was caused by a small localized pericardial effusion and presented as life-threatening obstructive shock. It is well known that rapid accumulation of as little as 150 mL of fluid may lead to marked increase in pericardial pressure and this can be accentuated by inflammatory stiffening of the pericardium [8]. Positive pressure ventilation may exaggerate the hemodynamic consequences of pericardial effusion through transmission of high positive intra-thoracic pressures to the pericardial space and may thus further compromise cardiac filling [9]. TTE permits prompt diagnosis and immediate bedside pericardiocentesis in acute life-threatening cases of cardiac tamponade [10].

Viral pericarditis is a common cause of pericardial effusion and may occasionally be complicated by cardiac tamponade. Although in most cases viral etiology is presumed by exclusion of other causes, definite diagnosis requires molecular testing of pericardial fluid and/or tissue [10]. Our patient’s fluid RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 was negative. In only one reported case pericardial fluid tested positive, albeit for a single target gene [7]. However, RT-PCR testing has several false negative results, necessitating repeat testing after 24−48 h in clinically suspected patients [11]. Moreover, it has been hypothesized that mechanisms other than direct virus invasion may be implicated in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19 patients, such as auto-immune type reactions through molecular mimicry or excessive recruitment of the immune system leading to a “cytokine storm” and exaggerated systemic inflammatory response [6,10]. Our patient’s high levels of serum inflammatory markers advocate the latter mechanism as a plausible pathogenetic scenario.

In conclusion, pericardial effusion causing cardiac tamponade may complicate severe COVID-19. Mechanical ventilation may exaggerate hemodynamic consequences leading to life-threatening shock necessitating prompt bedside therapeutic pericardiocentesis.

Authors’ contributions

VD and AK performed TTE and pericardiocentesis, DT, MK and KP contributed to data acquisition, EK, EP, II, DT prepared the draft, MD wrote the final manuscript as a corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This report did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images was obtained from the patient’s next of kin. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00898.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long B., Brady W.J., Koyfman A., Gottlieb M. Cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1504–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao C., Liu X., Zhang H., Li Y., Liu J. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) CT Findings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(6):701–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li K., Wu J., Wu F., Guo D., Chen L., Fang Z., Li C. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(6):327–331. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hua A., O’Gallahgher K., Sado D., Byrne J. Life-threatening cardiac tamponade complicating myo-pericarditis in COVID-19. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(22):2130. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dabbagh M.F., Aurora L., D’Souza P., Weinmann A.J., Bhargava P., Basir M.B. Cardiac tamponade secondary to COVID-19. JACC Case Reports. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.009. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farina A., Uccello G., Spreafico M., Bassanelli G., Savonitto S. SARS-CoV-2 detection in the pericardial fluid of a patient with cardiac tamponade. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:100–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito Y., Donohue A., Attai S., Vahdat A., Brar R., Handapangoda I. The syndrome of cardiac tamponade with “small” pericardial effusion. Echocardiography. 2008;25:321–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCanny P., Colreavy F. Echocardiographic approach to cardiac tamponade in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2017;39:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler Y., Charron P., Imazio M., Badano L., Barón-Esquivias G., Bogaert J. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015;2015(36):2921–2964. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.K. Hanson, A. Caliendo, C. Arias, J. Englund, M. Lee, M. Loeb, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines on the Diagnosis of COVID-19. Available at http://www.idsociety.org/COVID19guidelines/dx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.