Abstract

We elucidated the molecular cross-talk between cartilage and synovium in osteoarthritis, the most widespread arthritis in the world, using the powerful tool of single-cell RNA-sequencing. Multiple cell types were identified based on profiling of 10,640 synoviocytes and 26,192 chondrocytes: 12 distinct synovial cell types and 7 distinct articular chondrocyte phenotypes from matched tissues. Intact cartilage was enriched for homeostatic and hypertrophic chondrocytes, while damaged cartilage was enriched for prefibro- and fibro-, regulatory, reparative and prehypertrophic chondrocytes. A total of 61 cytokines and growth factors were predicted to regulate the 7 chondrocyte cell phenotypes. Based on production by > 1% of cells, 55% of the cytokines were produced by synovial cells (39% exclusive to synoviocytes and not expressed by chondrocytes) and their presence in osteoarthritic synovial fluid confirmed. The synoviocytes producing IL-1beta (a classic pathogenic cytokine in osteoarthritis), mainly inflammatory macrophages and dendritic cells, were characterized by co-expression of surface proteins corresponding to HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 or TLR2. Strategies to deplete these pathogenic intra-articular cell subpopulations could be a therapeutic option for human osteoarthritis.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Rheumatic diseases, RNA sequencing

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a leading cause of joint pain and disability and health-care costs worldwide1. Although OA is now considered a complex whole joint disease involving cartilage degeneration, osteophyte formation, subchondral sclerosis and inflammation of the synovial membrane2, little is known about the disruption of the physiological relationship and cross-talk between these tissues that contributes to the pathogenesis of OA. Thus, systematic molecular changes in the whole joint organ in human OA are still largely unknown and direct evidence of phenotypic and functional heterogeneity of both synoviocytes and chondrocytes has been lacking. The goal of this study was to elucidate the molecular cross-talk between cartilage and synovium and the contribution of the synovium to disease and cartilage degradation in OA using single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq).

scRNA-seq allows assessment of fundamental biological properties of cell populations and biological systems at an unprecedented resolution3. To date, most prior gene expression analyses of OA joint tissues, including our own, have performed “bulk” tissue analyses4–6. This is problematic for a tissue such as synovium, whose cellular constituents are known to be highly heterogeneous. Evidence suggests that many cell populations, including synovial fibroblasts7–10 and immune cells11–14, play a role in OA pathogenesis, although it is not clear which cell type may be most important at the various stages of OA development and severity. Bulk tissue analysis is also problematic for cartilage. Although cartilage has long been believed to consist of only one dominant cell type, recent evidence derived from other scRNA-seq studies suggests that cartilage contains cells of many different phenotypes15. The potential upstream regulators of these different chondrocyte phenotypes and the tissue(s) of origin of the regulators remain largely unknown. Such information could provide insights into the development and progression of OA from which new therapies might arise.

We performed single-cell transcriptomic analysis on OA knee joint tissues to systematically identify cell types and states within human osteoarthritic (OA) synovium and matched cartilage as well as determined regulators of these articular chondrocyte phenotypes. We used immunofluorescence analysis of synovial tissue to validate our scRNA-seq findings at a protein level and to spatially integrate discovered cell types and states into the anatomy of the OA synovium. Our results elucidate the contribution of synovium to disease and cartilage degradation and the cross-talk between OA synovium and cartilage, including the pathways and cell origin of mediators involved in the pathophysiology of OA. Surface markers, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 or TLR2, identified synoviocytes that co-expressed IL-1beta protein and other pro-inflammatory mediators, providing potential identifiers to aid targeting of these pathogenic intra-articular cell subpopulations for depletion or reprogramming.

Results

scRNA-seq reveals twelve distinct cell types in the synovium

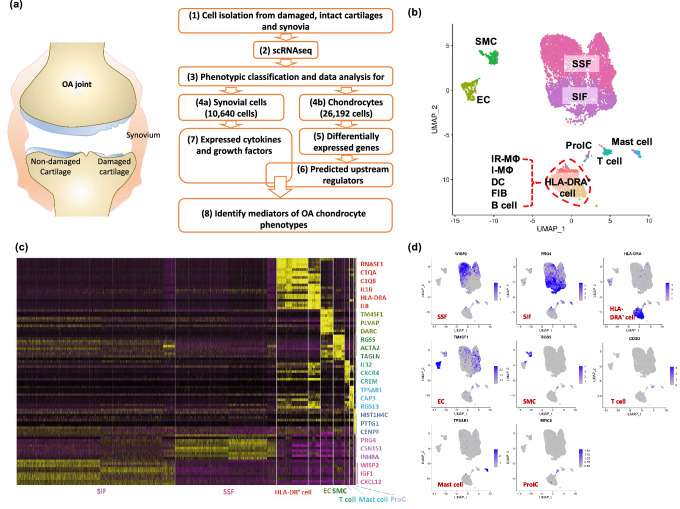

Profiling of 10,640 synoviocytes from a total of three individuals with knee OA (Fig. 1a) yielded a total of 21,253 identified genes. A total of 3,138 genes selected by unsupervised clustering revealed great heterogeneity of cell types, namely twelve distinct cell populations (Fig. 1b) including (from most to least abundant), synovial subintimal fibroblasts (SSF), synovial intimal fibroblasts (SIF), HLA-DRA+ cells (immune regulatory (IR-MΦ) and inflammatory macrophages (I-MΦ), dendritic cell (DC), activated pro-inflammatory (HLA-DRA+) fibroblasts (iFIB) and B cell clusters), smooth muscle cells (SMC), endothelial cells (EC), T cells, mast cells, and proliferating immune cells (ProIC). The identity of the 12 distinct cell subtypes could be confidently defined on the basis of the differentially expressed genes within each cell cluster (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Tables S1A,B). A representative gene for each cluster, mapped onto the UMAP plots, demonstrates the distinctly different nature of each major cell type (Fig. 1d). The majority of acquired synoviocytes were SSF and SIF (77.26%). These two cell types were readily distinguished in that SSF expresses collagen genes and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (CXCL12) for the synthesis of extracellular matrix components (Supplementary Fig. S1e–h); and SIF expresses genes producing essential constituents of synovial fluid including lubricin (PRG4) and hyaluronan (HAS1), and the synovial fibroblast biomarker, HTRA1, a secreted enzyme that regulates the availability of insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) by cleaving IGF-binding proteins (Supplementary Fig. S1i–k). Canonical gene markers for natural killer (NK) and NKT cells, NCAM1 (CD56)16,17 and ZBTB16 (PLZF)18,19, respectively, were not detected in the cell expression profiles of our OA synoviocytes.

Figure 1.

Single-cell RNA-Seq of human OA synoviocytes. (a) Flowchart shows the experimental strategy for systematically identifying cell diversity of synovium and cartilage in the pathogenesis of knee OA. (b) uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of scRNA-seq show unsupervised clusters colored according to putative cell types among a total of 10,640 cells in OA synovia. 44.1%, 33.2%, 12.82%, 3.63%, 3.28%, 1.35%, 1.13%, 0.49% of total acquired cells were synovial subintimal fibroblasts (SSF), synovial intimal fibroblasts (SIF), HLA-DRA+ cells (including immune regulatory [IR-MΦ] and inflammatory macrophages [I-MΦ], dendritic cells [DC], activated pro-inflammatory (HLA-DRA+) fibroblasts [iFIB] and B cells), endothelial cells (EC), smooth muscle cells (SMC), T cells, mast cells and proliferating immune cells (ProIC), respectively. (c) Heatmap of unsupervised clustering analysis shows the top ten highly expressed genes per cell type as determined by Seurat analysis with the top three genes per cluster highlighted on the right. Expression level is scaled based on z-score distribution. (d) Expression of the selected top marker genes for each cell type is shown in UMAP plots.

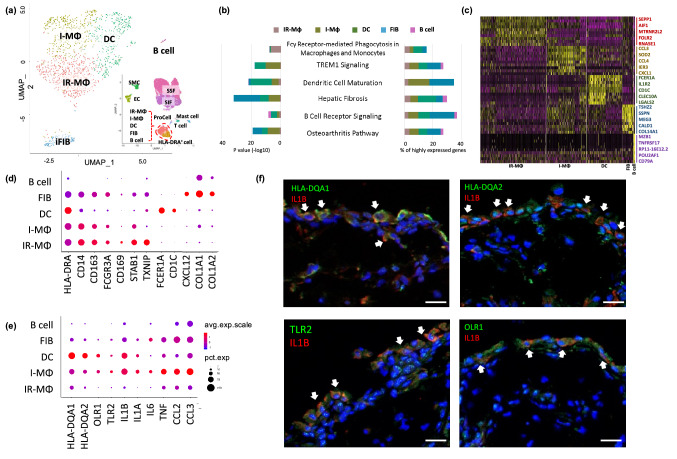

Identification of cell types in the HLA-DRA+ population

The HLA-DRA+ cell population comprised 12.8% of the total acquired cells in OA synovia and were enriched for cells with high expression of MHC class II genes, such as HLA-DRA, DRB1, DPA1 and DQA1. These cells comprised five subclusters or cell types consistent with heterogeneous groups of macrophages (IR-MΦ and I-MΦ), DC, iFIB and B cells (Fig. 2a). Pathways related to these cells included: Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis; TREM1 signaling, which plays important roles in innate immune responses, such as activating inflammatory responses20; dendritic cell maturation; hepatic fibrosis associated with an accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins21; the pathway related to B cell receptor signaling; and multiple cell populations associated with OA including I-MΦ, DC and iFIB (Fig. 2b). A heat map of the differentially expressed genes (p value threshold < 0.05 and log fold change (FC) > 0.25 compared to other clusters) for each HLA-DRA+ cell type demonstrates their distinctly different transcriptomes (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the HLA-DRA+ iFIB cells, like IR-MΦ, I-MΦ and DC, all expressed CD14 (Fig. 2d). The CD14+ iFIB were definitively identified as fibroblasts due to high expression of CXCL12 and collagen (COL1A1, COL1A2, COL3A1 and COL14A1) genes (Fig. 2d). Cell surface CD14 on blood-borne fibrocytes is a biomarker of cells that can rapidly enter sites of tissue injury and be involved in chemokine/chemokine receptor interactions22, suggesting a critical role for these iFIB cells in wound repair.

Figure 2.

Identification of specific HLA-DRA+ cell subtypes in OA synovia. (a) The HLA-DRA+ cell populations consisting of five distinct cell subtypes are shown in a UMAP plot. (b) Bar graphs demonstrate the top ranked canonical pathways associated with each cell subtype based on their percentage of highly expressed genes (right) and their significance (left). Pathways related to these cells include: Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis; TREM1 signaling; dendritic cell maturation; hepatic fibrosis; B cell receptor signaling; and multiple cell populations associated with OA. (c) Heatmap shows the top ten highly expressed genes for each cluster with the top five highly expressed genes per cluster highlighted on the right. The top highly expressed genes in IR-MΦ were SEPP1 and FLOR2 that are known to play a role in macrophage polarization and specifically expressed in regulatory macrophages, respectively. The top highly expressed genes in I-MΦ were inflammatory mediators, including CCL3 and CCL4. The top highly expressed genes in iFIB were collagen genes including COL14A1 and COL1A1. Consistent with identification as B cells were cells with high expression of MZB1, TNFRSF17 and CD79A. (d, e) The dot plots depict the average expression level (color scale) and percentage of cells expressing the selected marker genes (dot size) for each cluster. (d) The dot plot shows expression of HLA-DRA in all five cell subtypes and co-expression with an additional 11 markers (d) and additional immune markers and cytokines (e). (d) Classic macrophage marker genes (CD14, CD163 and FCGR3A) were highly expressed in IR-MΦ, I-MΦ and iFIB. Immune regulatory genes, CD169, STAB1 and TXNIP, were highly expressed in IR-MΦ. DC marker genes, FCER1A and CD1C were exclusively expressed in DC. Fibrous matrix genes (COL1A1 and COL1A2) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (CXCL12) were highly expressed in iFIB. (e) Surface maker genes (HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 and TLR2) and cytokines were highly expressed in I-MΦ and DC. (f) Representative immunofluorescence staining showing co-expression of IL1B and surface biomarkers of I-MΦ and DC, such as HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 and TLR2 in human OA synovium. Scale bar = 20 μm.

IR-MΦ differentially expressed genes for signaling pathways related to immune regulation such as Stabilin 1 (STAB1), a homeostatic receptor linking signals from extracellular to intracellular vesicular processes23, Thioredoxin Interacting Protein (TXNIP), an inhibitor of NF-κB activity24 and CD169, a macrophage specific marker of immunoregulation and inflammation25 (Fig. 2d and supplementary Fig. S2). We therefore confidently defined this macrophage cell type as an immune regulatory macrophage (IR-MΦ). I-MΦ like IR-MΦ expressed classic macrophage markers (such as CD163) but were distinguished from IR-MΦ by high expression of proinflammatory cytokine genes including IL1B, IL1A, IL6, TNF, CCL2, and CCL3 (Fig. 2e and supplementary Fig. S2a). DC also highly expressed these pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (Fig. 2e) and FCER1A, a high-affinity Fc-gamma receptor, and CD1C, biomarkers for classic dendritic cells26 (Fig. 2d and supplementary Fig. S2a). Interestingly, cell surface proteins encoded by HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 and TLR2 were more highly expressed in I-MΦ and DC than IR-MΦ suggesting they might be used to target pro-inflammatory cytokine producing cells (Fig. 2e). We evaluated expression levels of these genes in publicly available bulk RNA gene expression profiling data (GSE1919, GSE41038, GSE55457, GSE55235 and Lambert et al.’s study)27–30 from non-disease and OA synovial tissue (Supplementary Table S2). With the exception of TLR2, one or more of the datasets with publicly available data demonstrated an upregulation of each of these mediators in OA relative to control; in no case was there a down-regulation of any of these markers in OA relative to control. We also confirmed co-expression of these cell surface markers with IL-1beta protein (Fig. 2f). As expected, cytokines such as CCL3 protein were not expressed by IR-MΦ that were distinguished by their expression of CD169 and STAB1 proteins (Supplementary Fig. S2b,c.

Identification of chondrocyte phenotypes in OA

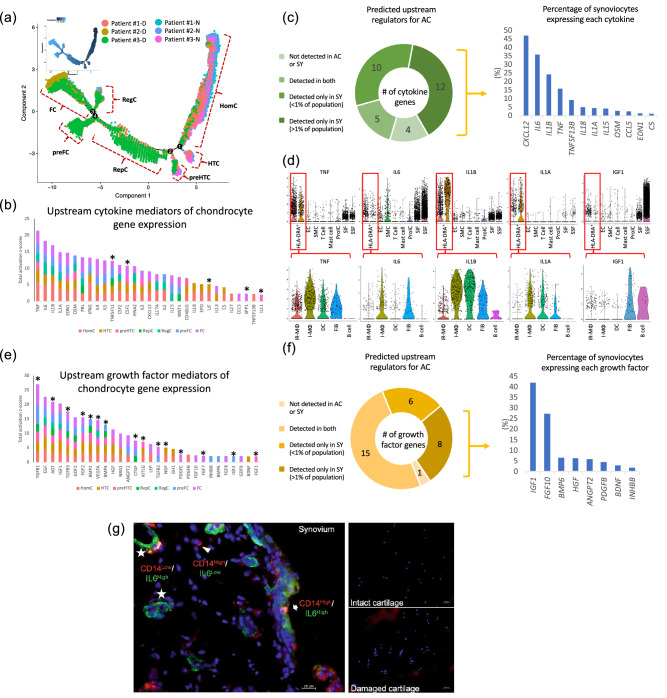

We isolated chondrocytes from articular cartilages collected from joint replacement surgery of patients with OA. We profiled a total of 26,192 cells, 14,613 cells from intact cartilage sites of the outer lateral tibiae (OLT), and 11,579 cells from damaged cartilage sites of the medial tibiae (MT) (Fig. 1a) yielding a total of 21,866 identified genes (20,770 from OLT and 21,034 from MT, 19,918 in common between them). Gene expression of chondrocytes from the more degenerated medial tibial plateau compared to the macroscopically normal outer lateral tibial plateau revealed marked gene expression differences in the two compartments (Supplementary Table S3). Chondrocytes from MT regions highly expressed numerous OA progression related genes, such as S100A4, COL1A1, COL1A25, COL5A115, TNFAIP631 and ADAMTS532. To gain insight into the transcriptional changes of chondrocytes in OA, we performed an unsupervised pseudotime trajectory analysis of the top 1,000 variably expressed genes yielding a total of seven distinct states/cell types of chondrocytes (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table S4). Similar to a previous study15, based on GO pathways of the differentially expressed genes, we identified homeostatic chondrocytes (HomC), hypertrophic chondrocytes (HTC), prehypertrophic chondrocytes (preHTC), regulatory chondrocytes (RegC) and fibrochondrocytes (FC) (Table 1). In addition, we also discovered two unique subtypes of chondrocytes, which we named based on their gene expression profiles, reparative chondrocytes (RepC), and prefibrochondrocytes (preFC) (Table 1). The preHTC and HTC cell types were similar (shared 57% of their differentially expressed genes); preFC and FC were also similar (shared 18% of their differentially expressed genes). HomC cells were distributed at the root of the trajectory, followed by a branch for HTC, preHTC, and RepC, followed by another three branches consisting of RegC, preFC and FC. Intact (lateral tibial) cartilage was enriched for HomC or HTC chondrocyte cell types, while damaged (medial tibial) cartilage was enriched for FC, preFC, RegC, RepC and preHTC (Fig. 3a). Key pathways in which these cell types are involved include modulation of cellular homeostasis in response to external stimuli (HomC), skeletal development (HTC and preHTC); ECM components (preHTC), extracellular matrix signaling and collagen fibril organization (RepC), ECM organization and disassembly (preFC and FC), signaling pathways related to response to endogenous stimuli and inhibition of biological processes (RegC) (Table 1). Interestingly, with respect to differential expression, the FC chondrocytes, enriched in damaged regions of cartilage, were the primary source of a host of OA related proteases (ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5, ADAMTS6 (also from preFC), MMP2, MMP14, HTRA1 (also from preFC)). The HomC and HTC chondrocytes, enriched in non-damaged cartilage, were primary sources of MMP3 and the anti-protease SERPINA1 (Alpha-1 antitrypsin), respectively.

Figure 3.

Identification of chondrocyte cell types in OA and the potential upstream regulators of these phenotypes. a shows a similarity across patients and a predominance of preFibrochondrocytes (preFC), Fibrochondrocytes (FC), Regulatory chondrocytes (RegC), Reparative chondrocytes (RepC) and some preHypertrophic chondrocytes (preHTC) in diseased areas designated ‘D’ corresponding to the medial tibial plateau (MT); a also shows a predominance of Homeostatic chondrocytes (HomC), some PreHTC and Hypertrophic chondrocytes (HTC) in non-diseased areas designated ‘N’ corresponding to OLT or the lateral tibial plateau. Potential upstream cytokines (b) and growth factors (e) were identified based on all highly expressed genes from each cluster and scaled by activation z-score; asterisks indicate the upstream mediators that were expressed by > 1% of acquired chondrocytes. Nearly all cytokines (c) and growth factors (f) were expressed by synoviocytes: 22 of 31 cytokines and 14 of 30 growth factors were only expressed by synoviocytes and not by chondrocytes (the proportion of acquired synoviocytes expressing each cytokine and growth factor are shown in the pie charts). (d) Violin plots show expression levels of representative cytokines (TNF, IL6, IL1B and IL1A) and a growth factor (IGF1) across all cell types in OA synovia and the HLA-DRA+ cell subtypes. (g) Representative immunofluorescence staining of synovium and cartilage (intact and damaged regions of a single patient specimen) for IL6 and CD14. As expected, the damaged cartilage is hypercellular compared to intact cartilage due to the development of multicellular chondrons in damaged cartilage with osteoarthritis. IL6 was highly expressed by CD14+ synovial fibroblasts (SSF, SSF and iFIB), I- MΦ, and SMC, but not chondrocytes from either intact or damaged regions of cartilage.

Table 1.

A summary of chondrocyte subtypes with key expressed genes and involved pathways.

| Cell type | Key genes | Key involved pathways | False discovery rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homeostatic chondrocyte (HomC) | MMP3, FOSB, JUN | Regulation of gene expression | 1.35E−09 |

| Response to external stimulus | 1.06E−09 | ||

| Hypertrophic chondrocyte (HTC) | COL10A1, IBSP, JUN | System development | 9.90E−09 |

| Multicellular organismal development | 3.89E−08 | ||

| Pre-hypertrophic chondrocyte (preHTC) | COL10A1, IBSP, COL2A1 | System development | 5.50E−09 |

| Skeletal system development | 6.63E−08 | ||

| Reparative chondrocyte (RepC) | COL2A1, CILP, COL3A1, COMP | Extracellular matrix organization | 3.98E−10 |

| Collagen fibril organization | 1.41E−06 | ||

| Pre-Fibrochondrocyte (preFC) | IL11, COL2A1, CILP, OGN | Extracellular matrix organization | 5.28E−22 |

| Extracellular matrix disassembly | 1.34E−08 | ||

| Fibrochondrocyte (FC) | COL1A1, COL1A2, S100A4, PRG4 | Extracellular matrix organization | 1.27E−33 |

| Movement of cell or subcellular component | 7.94E−17 | ||

| Regulatory chondrocyte (RegC) | CHI3L1, CHI3L2 | Negative regulation of biological process | 1.12E−04 |

| Cellular response to metal ion | 1.32E−06 |

Identification of potential upstream mediators regulating chondrocyte phenotypes in OA

Secreted inflammatory cytokines and growth factors are widely accepted as critical mediators of the disturbed homeostasis implicated in the pathophysiology of OA33. Therefore, potential upstream cytokine and growth factor regulators of the chondrocyte genes distinguishing each chondrocyte cell type were identified based on prior knowledge stored in the IPA database of expected effects between transcriptional regulators and their target genes. A total of 31 upstream cytokines with significant activation z-scores (z-scores ≥ 2, p values < 0.01) were identified (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S5A). We hypothesized that the main cytokine regulators were secreted by cells from synovial tissues. Based on a threshold of > 1% of cells expressing the gene, 17 of the 31 cytokines were expressed by synoviocytes. Twelve of the 31 cytokines (TNF, IL6, IL1B, IL1A, EDN1, OSM, CXCL12, IL15, IL18, C5, CCL5, TNFSF13B) were exclusively expressed by synoviocytes and not chondrocytes (in > 1% of synoviocytes but < 1% of chondrocytes); TNF, IL6, IL1B, and IL1A, were expressed by 16.16%, 36.17%, 24.44%, and 4.74% of acquired synoviocytes, respectively (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. S3 and S4, Supplementary Table S6). Except for B cells that lacked TNF expression, TNF was expressed by most HLA-DRA+ cells and most highly expressed by I-MΦ. IL1B and IL1A were most highly expressed by I-MΦ, DC, and iFIB. IL6 was expressed by I-MΦ, iFIB, SSF, SIF and SMC (Fig. 3d). For the OA-related cytokines, IL1A, IL1B, IL6 and TNF, whose average expression in synovium exceeded that of damaged cartilage by at least 25 fold, we were unable to detect any gene expression by chondrocytes from non-damaged and damaged full thickness regions of knee articular cartilage by qPCR in another independent OA cohort (n = 10) (Supplementary Fig. S5). Interestingly, based on the threshold of > 1% cells expressing the gene, only five of the total 31 predicted upstream cytokines were detected in chondrocytes, including TNFSF11, CSF1, LIF, SPP1 and IL11 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S5A). By scRNA data, among the 31 upstream cytokines, 3 cytokines (IFNA2, IL3, IL17A) were not detected in synovial or cartilage tissues. The remaining five cytokines (TNFSF11, CSF1, LIF, SPP1, IL11 and) were detected in both synoviocytes and chondrocytes; among these the expression of only one cytokine, SPP1, was far greater in chondrocytes than synoviocytes (Supplementary Table S5A).

A total of 30 upstream growth factors with significant activation z-scores were identified. Based on a threshold of > 1% of cells expressing the gene, 8 growth factors (IGF1, HGF, ANGP2, PDGFB, FGF10, INHBB, BMP6, BDNF) were exclusively expressed by synoviocytes, no growth factors were exclusively expressed by chondrocytes, while 15 (50%) of the 30 growth factors (TGFB1, TGFB2, TGFB3, AGT, FGF2, FGF7, BMP2, BMP4, VEGFA, CTGF, KITLG, NGF, PDGFC, IGF2, FGF1) were expressed by both synoviocytes and chondrocytes (Supplementary Table S5B and Fig. 3e, f). We confirmed (by ELISA, human protein cytokine array and in a few cases, by published literature) the protein expression in OA synovial fluid of the majority (19 of 20) of the upstream inflammatory cytokines and growth factors whose gene expression was in > 1% of acquired cells and predominant in synoviocytes (Table 2 and Supplementary Figs. S6, S7 and S8); only BMP6 was not detected in OA synovial fluid. By scRNA-seq data, one of the predicted growth factors, GDF2, was not detected.

Table 2.

Potential upstream regulators for OA pathogenesis from synoviocytes in OA synovial cells.

| Predicted upstream regulators for OA chondrocytes | Total activation z-scores | Proportion of expressing synoviocytes (%) | Proportion of expressing HLA-DR+ cells (%) | Highly expressing cell types | Concentration of detected mediator in OA SF | Method of detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokines | ||||||

| TNF | 21.32 | 16.16 | 60.26 | I-Mφ | 2.34 ± 0.74 pg/mL | Array* and Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| IL6 | 18.27 | 36.17 | 25.44 | I-Mφ, SSF, iFIB SMC | 105.76 ± 193.61 pg/mL | Array* and Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| IL1B | 17.01 | 24.44 | 61.88 | I-Mφ, DC | 1.02 ± 0.15 pg/mL | Array* and Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| IL1A | 14.82 | 4.74 | 29.91 | I-Mφ, DC | 2.90 ± 2.64 pg/mL | Array* and Chou CH et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| EDN1 | 14.73 | 1.93 | 1.98 | EC | 3.0 ± 0.5 pg/mL | Nahir et al. (PMID: 1865412) |

| OSM | 13.87 | 3.17 | 17.38 | HLA-DR+ cell Mast cell | 39.7 ± 108.0 pg/mL | Beekhuizen et al. (PMID: 24027021) |

| CXCL12 | 8.99 | 47.13 | 14.74 | SSF iFIB | ++ | Array* |

| IL15 | 7.84 | 4.72 | 8.43 | Many synovial cell types | 282.07 ± 203.47 pg/mL | Array* and Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| IL18 | 5.48 | 5.34 | 35.56 |

HLA-DR+ cell, Mast cell |

623.81 ± 266.43 pg/mL | ELISA§ |

| C5 | 4.16 | 1.45 | 1.17 | Many synovial cell types | +++ | Array* and Wang et al. (PMID: 22057346) |

| CCL5 | 2.24 | 2.84 | 4.91 | T cell | 305.52 ± 275.61 pg/mL | Array* and Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

| TNFSF13B | 2.22 | 9.66 | 31.89 | HLA-DR+ cell | +++ | Array* |

| Growth factors | ||||||

| IGF1 | 20.32 | 42.34 | 18.77 | SSF, iFIB, B cell | 9.4 ± 4 nM/L | Denko et al. PMID: 11048621 |

| HGF | 11.38 | 6.54 | 5.13 | SMC | 338.2 ± 966.9 pg/mL | Array* and Mabey et al. (PMID: 24966080) |

| ANGPT2 | 9.32 | 6.20 | 1.17 | EC, SMC | 0.54 ± 1.41 ng/mL | Array* and Mabey et al. (PMID: 24966080) |

| PDGFB | 2.60 | 4.81 | 27.27 | I-Mφ | + | Human XL cytokine array |

| FGF10 | 2.43 | 27.71 | 3.74 | iFIB | 3.01 ± 4.40 ng/mL | ELISA¶ |

| INHBB | 2.21 | 2.06 | 0.51 | Many synovial cell types |

Activin, 311 ± 80.2 pg/mL Inhibin, 2.15 ± 1.18 μg/mL |

El-Gendi et al. PMID: 20704626 |

| BDNF | 2.10 | 3.32 | 0.29 | Many synovial cell types | 224.76 ± 162.39 pg/mL | Chou et al. (PMID: 29129649) |

*Human XL cytokine array from R&D systems.

§IL-18 ELISA assay from Meso Scale Discovery.

¶FGF ELISA assay from LSBio.

Based on our data, four of the major OA-related cytokines (TNF, IL1B, IL1A and IL6) and a major OA-related growth factor (IGF1) were predominantly expressed by synoviocytes. The specific synovial cell types producing each of these upstream mediators are shown in violin plots (Fig. 3d). IL1A appeared to be exclusive to immune (HLA-DRA+) cells. TNF and IL1B were also primarily expressed by immune cells (HLA-DRA+). IL6 was primarily expressed by CD14+ synovial fibroblasts (SSF, SSF and iFIB), I-MΦ, and SMC (Fig. 3g). Interestingly, the proliferating immune cells (ProIC) of the synovium expressed low but detectable levels of TNF, IL1B and IL6.

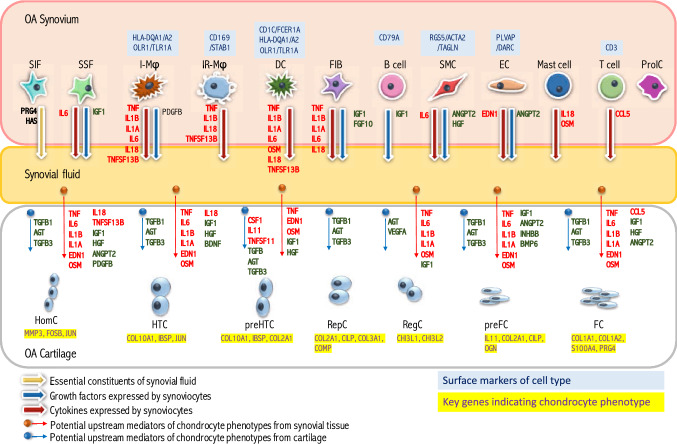

Collectively, our high-resolution single cell expression data provided insight into the spectrum of cellular heterogeneity within human OA cartilage and synovium. Twelve synovial cell types and 7 distinct chondrocyte cell types were identified in articular cartilage. Many of the signals regulating chondrocyte transcription in OA progression originate in the synovium, particularly from the I-MΦ and DC cell populations, not in the cartilage (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The cross-talk model of osteoarthritis. We identified 12 subpopulations from OA synovia and 7 distinct chondrocyte subpopulations from OA articular cartilage. We predicted potential upstream regulators of chondrocyte gene expression during OA progression to infer molecular cross-talk networks between cartilage and synovium. Genes expressed by OA chondrocytes and identified as potential mediators of chondrocyte phenotypes in OA are indicated by blue solid dots with arrows; the preponderance of growth factors, such as TGFB among them, is consistent with upregulation of anabolic processes to maintain cartilage homeostasis in OA. However, genes identified as potential mediators of chondrocyte phenotypes in OA that were exclusively expressed (in > 1%) by synoviocytes but not by any of the chondrocyte subtypes are indicated by red solid dots with arrows; among these were genes for several key pro-inflammatory cytokines implicated in the pathogenesis of OA, including IL1A, IL1B, IL6 and TNF that were specifically expressed by inflammatory macrophages (I-Mϕ), dendritic cells (DC) or other synoviocytes. I-Mϕ and DC expressed HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 or TLR2; these cells appeared to be the primary cytokine producing cells.

Discussion

Although substantial efforts have focused on molecular programs involved in OA progression among several types of human joint tissues4–6,15,34, only a few studies have examined molecular changes in multiple matched tissues in human OA4, and none have been carried out on a genomic scale. This study is the first, to our knowledge, that explored and characterized the cellular and transcriptional heterogeneity on a single cell level in matched cartilage and synovium from patients. To gain a deeper understanding of the biological cross-talk of tissues of the joint organ as they relate to the pathogenesis of OA, we evaluated the potential origins of upstream cytokines and growth factors that may control phenotypic changes of OA chondrocytes. Despite a limited number of study participants for scRNA-seq, we determined that the majority (55%) of key OA-related cytokines were produced by synoviocytes (expression of 38% of the cytokines was exclusive to synoviocytes based on an expression threshold of > 1% of cells) while only 16% of the cytokines were produced by chondrocytes; none were expressed exclusively by OA chondrocytes. We identified a distinct subset of HLA-DRA+ synoviocytes that highly expressed key pro-inflammatory cytokines related to the pathogenesis of OA, including IL1B, IL1A, IL6, TNF, CCL2 and CCL3. Importantly, these pro-inflammatory cytokine producing cells also highly expressed several genes encoding cell surface proteins including HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQA2, OLR1 and TLR2. Therapeutic strategies for OA, based on depleting or reprogramming these cells intra-articularly could be developed based on targeting these specific cell populations. Given the emerging observation that synovitis is present in early OA (patients who have minimal radiographic signs of cartilage loss), targeting of these specific cell populations may represent an opportunity for early therapeutic interventions35. However, conclusions on pathogenic mechanisms in this study are limited by the lack of non-OA controls and small sample size, therefore, a therapeutic strategy based on these results will require validation of these candidates as markers of pathogenic cell subsets in a larger patient population at different stages of OA and confirmation of their paucity in healthy normal non-arthritic synovium.

Several clinical studies have provided strong evidence that synovitis is associated with further worsening of OA structure36,37. Expression of IL1B, TNF, IL6, IL15 and IL18, some of the most extensively studied cytokines in OA, was detected in < 1% of chondrocytes but in 5–36% of synoviocytes ranging from sixfold (IL15) to 291 fold (IL1B) greater expression in synoviocytes compared to MT chondrocytes from damaged regions of cartilage (Supplementary Table S6); these key cytokines were predicted to be upstream regulators for altering the course of disease at the level of cellular communication for chondrocytes. These cytokines, up-regulated in OA, lead to cartilage degradation and have synergistic effects on signaling pathways that increase inflammation and cartilage breakdown38. TNF and IL1B are key inflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of OA by promoting catabolic and destructive processes39; they can also block chondrocyte synthesis of ECM components, such as type-II collagen40,41. Both TNF and IL1B were expressed in up to 60% of HLA-DRA+ acquired cells in synovial tissues. TNF was significantly highly expressed in I-MΦ and may modulate the phenotypic changes for all states of chondrocyte populations, except RepC. IL1B was significantly highly expressed in I-MΦ and DC, and was identified as an upstream regulator for all states of chondrocyte populations, except RepC and preHTC. The antagonist of IL-1beta, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra, gene ILRN), was expressed by < 1% of chondrocytes from the MT damaged cartilage and not detected by scRNA-seq of chondrocytes from non-damaged regions; lack of this specific countermeasure in cartilage may be one reason why IL-1beta is such a potent OA promoting cytokine. This observation is congruent with recent evidence demonstrating the importance of IL1RN genetic polymorphisms (that impact IL-1Ra protein levels) for incidence and severity of OA42.

IL6, a pleiotropic cytokine with pro- and anti-inflammatory properties43, was widely expressed by synoviocytes (36.17% of acquired cells) and significantly differentially expressed in I-MΦ, SSF, iFIB and SMC, which may modulate and regulate the phenotypic changes for HomC, HTC, RegC, preFC and FC. IL18, another cytokine belonging to the IL1 superfamily, was mainly expressed in HLA-DRA+ cells and mast cells and may affect the phenotypic changes of HomC and HTC. IL15, whose synovial fluid expression is known to be elevated in early stages of OA44, was expressed in 4.72% of acquired synoviocytes and may modulate RegC, preFC and FC; this is of particular importance given that the FC (and preFC) appear to be important for disease related protease production.

By both average gene expression and percentage of expressing cells, genes for key OA-related proteases (Supplementary Table S6), such as aggrecanases (ADAMTS4 and ADAMTS5), predominated in synovium compared with cartilage. Expression of cathepsins (B, D and K) were similar for synovium and cartilage. Of the many metalloproteinases (MMPs) in humans, those reported to cleave triple-helical collagen are the collagenases (MMP-1, MMP-8, and MMP-13), gelatinase A (MMP-2), membrane type 1 MMP (MMP-14), and weakly, membrane type 2 MMP (MMP-15)45; of these, only MMP1 (synoviocytes only), MMP2 and MMP14 (both synoviocytes and chondrocytes) were detected. Thus, although both MMP-1 and MMP-13 are considered rate-limiting in the process of collagen degradation46, at the gene expression level, only MMP1 was detected and only in synoviocytes. MMP-2, MMP-3 and MMP-9 are elevated in arthritis, and degrade denatured and non-fibrillar collagen and non-collagen matrix components of joints46. In addition, MMP-3 can also activate other MMPs such as MMP-1, MMP-7, and MMP-9, rendering MMP-3 crucial in connective tissue remodeling46. MMP3 was highly expressed (based on both average cell expression and % of cells expressing) by both synoviocytes and chondrocytes; MMP2 and MMP3 were expressed by both synoviocytes and chondrocytes while MMP9 was only expressed by synoviocytes (based on the threshold of > 1% cells expressing). With the exception of IL1RN described above, countermeasures, such as SERPINA1 (alpha-1-antitrypsin) and the TIMPs (tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases) appeared to be robustly expressed by both synoviocytes and chondrocytes. Notably, ADAM12 and CTSS were found to be preferentially expressed in chondrocytes in MT over OLT. These proteases could contribute to an exacerbation of the cartilage damage given that MT is usually the most affected region of an OA knee. Thus, these scRNA-seq data provide unique insights into the potential origin of many proteases involved in degradation of tissues in OA; taken together, the data underscore a key role of OA synovium as a source of proteolytic activity in addition to the pro-inflammatory cytokines that regulate these proteases.

A novel IR-MΦ population was identified in our study characterized by high expression of immune regulatory genes, including STAB1, TXNIP and CD169. The role of this macrophage subtype in OA is unclear. STAB1 is an endocytic scavenger receptor known to be expressed in alternatively activated macrophages participating in anti-inflammatory responses and phagocytosis47. Expression of STAB1 allows macrophages to retain immunosuppressive activity48 and maintain tissue homeostasis via suppressing production of the profibrogenic chemokine CCL349. TNXIP, a suppressor of TNF-α–activated NF-κB activity and an activator of IL-1beta secretion via interaction with NLPR350, was also highly expressed in IR-MΦ, supporting the potential immune regulatory activity of the IR-MΦ population in OA. On the other hand, CD169, known as sialoadhesin, is a cell adhesion molecule found on the surface of macrophages present in affected tissues from patients with inflammatory disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis51,52. CD169 has been shown to mediate both immunity and immune tolerance for macrophages and is considered a biomarker for highly pathogenic phagocytes, but the precise mechanisms remain unclear25. Taken together, this IR-MΦ population may play a role in clearance of cell remnants and degraded tissues and modulate immune responses of the synovium.

Despite the fact that cartilage has long been thought to consist of only one dominant cell type, consistent with a prior study15, we too identified multiple cell types in articular OA cartilage. In our study, using a different methodology and strategy for sample harvesting and processing compared with the previous study, we discovered five similar chondrocyte populations (HomC, preHTC, HTC, RegC, and FC) and two additional distinct chondrocyte populations (RepC and preFC). Three of their OA chondrocyte populations were not definitively identified in our analysis, including effector chondrocytes (EC), proliferative chondrocytes (ProC), and cartilage progenitor cells (CPC). Their EC were enriched for genes related to metabolism and cholesterol synthesis, such as C2orf82, CLEC3A and CYTL1; our RepC cluster was the most closely related population given differential expression for these marker genes. Their ProC population was enriched for genes related to RNA metabolic processes and RNA stabilization; our HomC population was the most similar given enrichment for genes involved in regulation of RNA splicing, RNA binding and Poly(A) RNA binding. However, their markers of CPC (BIRC5, CENPU, UNE2C, DHFR and STMN1) related to human OA cartilage regeneration were not significantly expressed in any of our putative chondrocyte populations.

HomC cells highly expressed genes for modulating cellular homeostasis (MMP3, FSOB and JUN) in response to external stimuli. Both HTC and preHTC highly expressed genes related to skeletal development (COL10A1 and IBSP); 56.67% of the differentially expressed genes were differentially expressed in both HTC or preHTC. HTC were enriched in genes related to cellular homeostasis (JUN, FOS and TF); preHTC were enriched in genes related to ECM component (CLEC3A, COL9A2 and COL11A2).

RepC were enriched for extracellular matrix signaling and collagen fibril organization, such as COL2A, CLEC3A, CILP and COMP, indicating a high reparative ability. Both FC and preFC highly expressed a fibroblast-related gene, CD55, and were enriched mainly for type I collagen organization and ECM assembly (COL1A2, COL5A1, and HTRA1); these two cell states also shared 18.38% of their differentially expressed genes. PreFC highly expressed IL11 that plays an essential role in ERK-dependent autocrine signaling and is required for initiation of fibrogenic protein synthesis53. FC were enriched for genes related to cell migration (TMSB4X) and vasculature (S100A4) as well as several OA related aggrecanases54 (ADAMTS1, ADAMTS5) and other proteases (MMP2, MMP 14 and HTRA1) suggesting they play a key role in OA pathogenesis. RegC were enriched for genes of signaling pathways related to response to endogenous stimuli and inhibition of biological processes (CHI3L2, CLU, CHI3L1 and CRTAC1).

Non-OA healthy control synovium was unavailable for our research therefore we could not directly address the differences in cell patterns between OA and non-OA synovium. There is in general a significant knowledge gap in the literature concerning gene expression of non-arthritic healthy synovium and considerable ethical challenges to acquiring such samples. A number of studies have attempted to fill this knowledge gap but data from these synovial tissues have major limitations as they have been acquired as cadaveric tissue27,29, from traumatic joint injury29,35,55, by arthroscopy for unspecified indication28, or from normal appearing areas of synovium within an OA joint30. Additionally, the confound of time from event to tissue acquisition was not described for these studies. To our knowledge, scRNA-seq of control healthy synovial cells has also not been published. Ungethuem et al.27, who performed bulk RNA gene expression profiling and validation in OA, RA and non-disease synovial tissues derived from fatal accidents, identified 262 significantly differentially up-regulated genes in OA compared to non-disease synovial tissues (their Supplementary Tables S1A,B). A total of 34 of these 262 up-regulated genes were identified as differentially and highly expressed in the HLA-DR+ clusters of our study, including AIF1, FLOR2, HLA-DMA, HLA-DMB and HLA-DQB1. However, several well-known OA associated proinflammatory cytokines expressed in the HLA-DR+ clusters, such as TNF and IL1B, were down-regulated in OA and RA synovial tissues in Ungethuem’s study relative to normal donors (from fatal trauma). Such genes may be highly induced by an acute inflammatory response to trauma or post-mortem, indicating the limitations and challenges to acquiring non-disease controls in gene expression studies of synovial tissues.

Enzymatic isolation may alter the metabolic activity and growth rate of chondrocytes. Our protocol for chondrocyte isolation was designed to minimize cell stress, maximize cell viability and retain native cell phenotypes; our protocol succeeded in yielding 90% viable cells and a cell yield of 7.60 ± 0.92 × 105/g wet weight of cartilage. However, it is possible that longer digestion periods would favor higher cell yields and reveal additional cell phenotypes or proportions of cells of the different phenotypes than identified with the shorter enzymatic digestion protocol. We do not believe this is a major limitation since Hayman 2006 et al.56 showed that the cell yield of a short pronase/collagenase protocol for 4.5 h (our protocol was identical but for a total of 3 h) was the same as the yield from the digestion of cartilage with collagenase for 22 h from a standardized 6-mm-diameter punch-biopsy of cartilage.

Steroid injection is a standard treatment modality for painful OA of the knee. While this anti-inflammatory treatment reduces pain, it does not prevent disease progression and recent data suggest that it may even exacerbate it57. This suggests that a more precise strategy would be needed for disease course modification. Our insights could open up new avenues for therapeutic intervention, including potential disease modifying approaches, such as the use of targeted biologics vs. the more common approach of pain modulation based on patient reported outcomes. Senescent cells have a proinflammatory phenotype58 and their presence was recently reported to increase in knee OA patients59. Senolysis (i.e. the therapeutic elimination of senescent cells), therefore, is an appealing precision strategy for the treatment of OA supported by preclinical model efficacy60. This strategy has shown promise in a murine model of OA and senolytic agents are in development for OA in humans61. Based upon a phase I study, a senolytic inhibitor of the MDM2/p53 protein–protein interaction (UBX0101) was well-tolerated and demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction of knee OA pain following a single IA injection. It will be of great interest in future studies to correlate senescence markers with the various synovial and chondrocyte cell types to determine the precise cell phenotypes targeted by senolytic strategies. Other disease modifying strategies are currently under investigation in clinical trials (ADAMTS-5 inhibitor (GLP1972), a Wnt inhibitor (SM04690), and the growth factor, FGF-18 (Sprifermin)), but none of them are believed to be targeting a specific cellular subset.

In summary, using a methodology that provides a characterization of cartilage and synovium proximal to the disease process and without cell culture, we identified 7 major states (cell populations) and 12 major cell clusters in human OA cartilages and synovia, respectively. Putative upstream cytokines (n = 31) and growth factors (n = 30) were linked to phenotypic changes of OA chondrocytes. Among these upstream regulators, 12 cytokines and 7 growth factors were expressed by synoviocytes and detected in synovial fluid, with no expression detected in chondrocytes. Based on our data, immune subsets including macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells and T cells, activated fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells likely contribute to OA disease etiology and progression through expression of proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors, such as IL1A, IL1B, TNF, IL6 and IGF1. In particular, key OA inflammatory mediators, such as TNF, IL1B and IL6, were mainly produced and released to the joint space by HLA-DRA+ synoviocytes (macrophages and DC), but not chondrocytes. These results provide a unique perspective on OA that suggests that synovial cell populations play a major role in the pathogenesis of cartilage degradation of OA. Thus, this scRNA-seq study has identified the origin of key pathogenic catabolic and anabolic mediators in OA that could allow more focused tissue specific targeting of pathogenic cells and molecules in strategies to treat OA.

Methods

Acquisition and processing of synovial and cartilage tissue and synovial fluid

Matched articular cartilage, synovial membrane and synovial fluid biospecimens were acquired as anonymized surgical waste from 22 patients, mean age 69.1 (SD 7.0) years, 72% (n = 16) female, mean BMI 29.3 (SD 5.9) kg/m2, all undergoing total knee replacement for medial compartment dominant knee OA. Joint tissues (cartilage and synovial membrane) from 3 OA patients of mean age 67.7 (SD 2.31) years, 2 female, BMI 39 (SD 4.6) kg/m2 were randomly selected, from the total of 22, for scRNA-seq analysis. Use of samples from 22 patients were as follows: 3 were used for scRNAseq and an additional 9 patients’ samples were used for synovial fluid analyses; 5 of these additional 9 patients’ cartilage and synovial membrane specimens were used for confirmatory immunofluorescence; samples from the remaining 10 patients were utilized for cartilage RNA isolation for qPCR validation of gene expression. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University and conformed to the relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. For acquisition and use of biospecimens other than the anonymized surgical waste tissue, which was exempt humans subjects research, Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

We harvested the outer lateral (intact) and inner medial (damaged) tibial articular cartilages for isolation of cells or extraction of cartilage matrix. The anatomic orientation was indicated on the freshly isolated specimens by marker pen to ensure consistency of sampling at prespecified regions of interest. All joint specimens were processed within 2 h of procurement (time of surgery for joint replacement). For chondrocyte dissociation, the tibial plateaus were washed three times with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Thermo scientific, IL). Cartilage (~ 1 g) from intact and damaged regions of interest was minced finely with a sterile scalpel and collected in a 15 ml tube. Adjacent sections and matched synovial tissue were preserved for histological evaluation of OA severity and for immunofluorescence staining. A two-step procedure for cell isolation from cartilage was used, consisting of an initial tissue digestion with pronase, followed by collagenase. A total of 15 mls of 1% Pronase (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) made up in DMEM/F12 (Thermo scientific, IL) and sterile filtered with a 0.22 μm filter (Sigma-Aldrich, MO), was added to minced cartilage tissue, incubated for 30 min at 37 °C rotating at 250 revolutions/mins (rpm), and then washed twice with PBS. A total of 15 mls of 0.4% Collagenase type II from Clostridium histolyticum (Sigma-Aldrich, Mo) made up in DMEM/F12 and sterile filtered with a 0.22 μm filter, was added to the cartilage residua (after pronase treatment), incubated for 150 min at 37 °C rotating at 250 rpm. After enzymatic digestion, cells were pelleted by centrifugation, washed, sieved through a 30 μm cell strainer (Miltenyi Biotec, CA), pelleted by centrifugation again and resuspended in 1 ml PBS. Synovial membranes (~ 1 g) were dissected into small pieces, digested with 0.1% Collagenease Type IV from Clostridium histolyticum (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) in 50 mls DMEM/F12 for 1 h at 37 °C rotating at 250 rpm, then washed twice with PBS. After lysing red blood cells with 5 mls ACK lysis buffer (Thermo scientific, IL), cells were centrifuged, washed, and sieved through a 30 μm cell strainer (Miltenyi Biotec, CA), pelleted by centrifugation again and resuspended in 1 ml PBS.

RNA-seq library preparation and sequencing

Cells were prepared for cDNA amplification and chromium library construction using single-cell RNA-Seq library kit v2 according to the manufacturers’ recommendations (10 × Genomics, CA) by the Molecular Genomics Core facility at the Duke Molecular Physiology Institute (DMPI). cDNA libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 4,000 with read length of 150 bp by the Duke Center for Genomic and Computational Biology (GCB) core facility.

Analysis of scRNA-seq data

The primary analysis of the scRNA-seq data followed the recommended protocols from 10X Genomics. Briefly, we demultiplexed raw base call (BCL) files generated by Illumina sequencers into FASTQ files, upon which alignment was carried out to the h19 human transcriptome; filtering, barcode counting, and UMI counting were performed using Cell Ranger software version 3.1 and default parameters (10X Genomics). The secondary statistical analysis was performed using the R package Seurat62, which performed quality control and subsequent analyses on the feature-barcode matrices produced by Cell Ranger. In Seurat, data were first normalized and scaled after basic filtering for minimum gene and cell observance frequency cut-offs63. We then examined the data and performed further filtering (nFeature 7,500, nCount 100,000, percent_mt 0.3) based on a range of metrics in an attempt to identify and exclude possible multiplets (i.e. instances where more than one cell was present and sequenced in a single emulsified gel bead). The removal of further technical artifacts was performed using regression methods to reduce noise63.

After quality control procedures were complete, we performed linear dimensional reduction, calculating principal components using the most variably expressed genes in our dataset63. The genes underlying the resulting principal components were examined to confirm they were not enriched in genes involved in cell division or other standard cellular processes64. Significant principal components for downstream analyses were determined through methods mirroring those implemented by Macosko et al64, and these principal components were carried forward for two main purposes: to perform cell clustering and to enhance visualization63. Cells were grouped into an optimal number of clusters for de novo cell type discovery using Seurat’s FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions63; graph-based clustering approaches with visualization of cells was achieved through the use of manifold learning technique UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection)65, which reduces the information captured in the selected significant principal components to two dimensions63. In total, 14,613, 11,579 and 10,640 cells from intact cartilage, damaged cartilage and synovium, respectively, were used for downstream analyses. Differentially expressed genes for a particular cell type were defined by a p value threshold < 0.05 and log FC > 0.25; all provided p values were adjusted by Bonferroni correction.

Our analysis revealed 12 distinct cell types with a total of fifteen clusters visualized using UMAP in synovial tissues (Supplementary Fig. S1). Clusters 0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, could be further divided into 2 distinct subtypes, SSF and SIF (Supplementary Fig. S1a,b): We also observed four immune subpopulations (clusters 3, 9, 12 and 13) that all expressed PTPRC (CD45) (Supplementary Fig. S1l), and three unique subpopulations, clusters 10, 11 and 14, that expressed specific markers of known cell types, including EC (PLVAP), SMC (ACTA2) and ProIC (HIST1H4C, BIRC5, and CCL3), respectively. T cells in cluster 12 and mast cells in cluster 13 highly expressed CD3 and TPSAP1, respectively. Proliferating immune cells (ProIC) in cluster 14, expressing genes related to immune cell markers (HLA-DRA and PTPRC), were also characterized by high differential expression of genes responsible for regulation of cell division, the cell cycle, chromatin structure regulation and apoptosis inhibition (namely CENPF, CDK1, HIST1H4C and BIRC5). Overall, among these 15 clusters, there were eight distinct cell populations observed from each of three patients, including SSF, SIF, HLA-DRA+ cells, EC, SMC, T cells, mast cells, ProIC; the HLA-DRA+ subtype could be further subdivided into 5 cell types for a total of 12 distinct cell types.

The methods for upstream mediator analysis, Trajectory Analysis, qRT-PCR for validation of gene expression in cartilage and immunofluorescence staining for detection of cytokine expression are described in Supplementary Information (Supplementary Methods).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This is an investigator-initiated study funded in part by Unity Biotechnology but this sponsorship did not influence the data or decision to publish the data. This study was also funded in part by NIH/NIA P30 AG028716 that supported effort of CHC and VBK. We thank E. Hocke and K. Abramson for help with library preparation and consultation (Duke Molecular Physiology Institute Molecular Genomics core). We thank Rathi Ryan for helpful discussions about the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: C.H.C., C.B.Y., R.M.L., V.B.K.; Performed the experiments and analyzed the data: C.H.C., J.G., V.J., C.A.H.; Carried out sample collection: C.H.C., D.E.A., C.A.H.; Completed the single cell sequencing and performed sequencing analysis: J.G., S.G.; Wrote the manuscript: C.H.C., V.J., J.G., V.B.K. All authors reviewed, edited and approved this manuscript for publication.

Data availability

There are no restrictions on the availability of materials or information once the manuscript is published. All RNAseq data are available at NCBI GEO GSE152805.

Competing interests

C.H.C., V.J., J.G., D.E.A., C.A.H. and S.G. declare no competing interests. C.B.Y. and R.M.L. are employees of Unity Biotechnology and played a role in the conceptualization of the study and in preparation of the manuscript. This work was funded in part by Unity Biotechnology, however, Unity Biotechnology had no role in the preparation of the manuscript, data collection or decision to publish this study. V.B.K. has been a periodic consultant for Unity Biotechnology providing periodic advice on clinical study design, unrelated to this study and has no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ching-Heng Chou and Vaibhav Jain.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-67730-y.

References

- 1.Xie F, et al. Economic and Humanistic Burden of Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Large Sample Studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34:1087–1100. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:1697–1707. doi: 10.1002/art.34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olsen TK, Baryawno N. Introduction to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2018;122:e57. doi: 10.1002/cpmb.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou CH, et al. Direct assessment of articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone reveals a progressive gene expression change in human osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chou CH, et al. Insights into osteoarthritis progression revealed by analyses of both knee tibiofemoral compartments. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23:571–580. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou CH, et al. Genome-wide expression profiles of subchondral bone in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:R190. doi: 10.1186/ar4380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith MD. The normal synovium. Open Rheumatol J. 2011;5:100–106. doi: 10.2174/1874312901105010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revell, P. A., al-Saffar, N., Fish, S. & Osei, D. Extracellular matrix of the synovial intimal cell layer. Ann. Rheum. Dis.54, 404–407 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Jay GD, Britt DE, Cha CJ. Lubricin is a product of megakaryocyte stimulating factor gene expression by human synovial fibroblasts. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:594–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamer TM. Hyaluronan and synovial joint: function, distribution and healing. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013;6:111–125. doi: 10.2478/intox-2013-0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein-Wieringa IR, et al. Inflammatory Cells in Patients with Endstage Knee Osteoarthritis: A Comparison between the Synovium and the Infrapatellar Fat Pad. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:771–778. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.151068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lange-Brokaar, B. J. et al. Synovial inflammation, immune cells and their cytokines in osteoarthritis: A review. Osteoarthr. Cartil.20, 1484–1499. 10.1016/j.joca.2012.08.027 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Sokolove J, Lepus CM. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2013;5:77–94. doi: 10.1177/1759720X12467868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culemann S, et al. Locally renewing resident synovial macrophages provide a protective barrier for the joint. Nature. 2019 doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1471-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Q, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq analysis reveals the progression of human osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78:100–110. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson MJ, Ritz J. Biology and clinical relevance of human natural killer cells. Blood. 1990;76:2421–2438. doi: 10.1182/blood.V76.12.2421.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovalovsky D, et al. The BTB-zinc finger transcriptional regulator PLZF controls the development of invariant natural killer T cell effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1055–1064. doi: 10.1038/ni.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gapin L. The making of NKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1009–1011. doi: 10.1038/ni0908-1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colonna M, Facchetti F. TREM-1 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells): a new player in acute inflammatory responses. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl 2):S397–S401. doi: 10.1086/374754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safadi R, Friedman SL. Hepatic fibrosis–role of hepatic stellate cell activation. MedGenMed. 2002;4:27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kzhyshkowska J, Gratchev A, Goerdt S. Stabilin-1, a homeostatic scavenger receptor with multiple functions. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:635–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim MJ, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor interacts with thioredoxin-interacting protein and induces NF-kappaB activity. Cell Signal. 2017;34:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Neill AS, van den Berg TK, Mullen GE. Sialoadhesin - a macrophage-restricted marker of immunoregulation and inflammation. Immunology. 2013;138:198–207. doi: 10.1111/imm.12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDonald KP, et al. Characterization of human blood dendritic cell subsets. Blood. 2002;100:4512–4520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ungethuem U, et al. Molecular signatures and new candidates to target the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Physiol Genomics. 2010;42A:267–282. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00004.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas GP, et al. Expression profiling in spondyloarthropathy synovial biopsies highlights changes in expression of inflammatory genes in conjunction with tissue remodelling genes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:354. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woetzel D, et al. Identification of rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis patients by transcriptome-based rule set generation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16:R84. doi: 10.1186/ar4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambert C, et al. Gene expression pattern of cells from inflamed and normal areas of osteoarthritis synovial membrane. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:960–968. doi: 10.1002/art.38315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou CH, Attarian DE, Wisniewski HG, Band PA, Kraus VB. TSG-6 - a double-edged sword for osteoarthritis (OA) Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2018;26:245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glasson SS, et al. Deletion of active ADAMTS5 prevents cartilage degradation in a murine model of osteoarthritis. Nature. 2005;434:644–648. doi: 10.1038/nature03369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapoor M, Martel-Pelletier J, Lajeunesse D, Pelletier JP, Fahmi H. Role of proinflammatory cytokines in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:33–42. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soul J, et al. Stratification of knee osteoarthritis: two major patient subgroups identified by genome-wide expression analysis of articular cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:423. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanus DE, et al. Regulation of the Inflammatory Synovial Fibroblast Phenotype by Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 Long Noncoding RNA in Obese Patients With Osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:609–619. doi: 10.1002/art.41158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conaghan PG, et al. Clinical and ultrasonographic predictors of joint replacement for knee osteoarthritis: results from a large, 3-year, prospective EULAR study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:644–647. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins JE, et al. Semiquantitative Imaging Biomarkers of Knee Osteoarthritis Progression: Data From the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health Osteoarthritis Biomarkers Consortium. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2422–2431. doi: 10.1002/art.39731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojdasiewicz P, Poniatowski LA, Szukiewicz D. The role of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:561459. doi: 10.1155/2014/561459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson B, Pettipher ER. Arthritogenic actions of recombinant IL-1 and tumour necrosis factor alpha in the rabbit: evidence for synergistic interactions between cytokines in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;75:306–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seguin CA, Bernier SM. TNFalpha suppresses link protein and type II collagen expression in chondrocytes: Role of MEK1/2 and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2003;197:356–369. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shakibaei M, Schulze-Tanzil G, John T, Mobasheri A. Curcumin protects human chondrocytes from IL-l1beta-induced inhibition of collagen type II and beta1-integrin expression and activation of caspase-3: an immunomorphological study. Ann Anat. 2005;187:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Attur M, et al. Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN) gene variants predict radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis and risk of incident disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:400–407. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheller J, Chalaris A, Schmidt-Arras D, Rose-John S. The pro- and anti-inflammatory properties of the cytokine interleukin-6. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813;878–888:2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scanzello CR, et al. Local cytokine profiles in knee osteoarthritis: elevated synovial fluid interleukin-15 differentiates early from end-stage disease. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:1040–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu Z, Visse R, Inouye M, Nagase H, Brodsky B. Defining requirements for collagenase cleavage in collagen type III using a bacterial collagen system. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:22988–22997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.348979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mehana EE, Khafaga AF, El-Blehi SS. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in osteoarthritis pathogenesis: An updated review. Life Sci. 2019;234:116786. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.116786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park SY, et al. Stabilin-1 mediates phosphatidylserine-dependent clearance of cell corpses in alternatively activated macrophages. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3365–3373. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunkel J, et al. Enhanced Antibody Production in Clever-1/Stabilin-1-Deficient Mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2257. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rantakari P, et al. Stabilin-1 expression defines a subset of macrophages that mediate tissue homeostasis and prevent fibrosis in chronic liver injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:9298–9303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1604780113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nasoohi S, Ismael S, Ishrat T. Thioredoxin-Interacting Protein (TXNIP) in Cerebrovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Regulation and Implication. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55:7900–7920. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-0917-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bogie JF, et al. CD169 is a marker for highly pathogenic phagocytes in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:290–300. doi: 10.1177/1352458517698759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hartnell A, et al. Characterization of human sialoadhesin, a sialic acid binding receptor expressed by resident and inflammatory macrophage populations. Blood. 2001;97:288–296. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schafer S, et al. IL-11 is a crucial determinant of cardiovascular fibrosis. Nature. 2017;552:110–115. doi: 10.1038/nature24676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Longpre JM, et al. Characterization of proADAMTS5 processing by proprotein convertases. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2009;41:1116–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Q, et al. Identification of a central role for complement in osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 2011;17:1674–1679. doi: 10.1038/nm.2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayman DM, Blumberg TJ, Scott CC, Athanasiou KA. The effects of isolation on chondrocyte gene expression. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2573–2581. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McAlindon TE, Harkey MS, Ward RJ, Hochberg MC, Driban JB. Intra-articular Corticosteroid Injections in the Hip and Knee: Perhaps Not as Dangerous as They Want You to Believe? Radiology. 2020;295:249–250. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coppe JP, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:2853–2868. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Del Rey MJ, et al. Senescent synovial fibroblasts accumulate prematurely in rheumatoid arthritis tissues and display an enhanced inflammatory phenotype. Immun Ageing. 2019;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12979-019-0169-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeon OH, et al. Local clearance of senescent cells attenuates the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis and creates a pro-regenerative environment. Nat. Med. 2017;23:775–781. doi: 10.1038/nm.4324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsu, B. et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and clinical outcomes following single-dose IA administration of UBX0101, a senolytic MDM2/p53 interaction inhibitor, in patients with knee OA. Arthritis Rheumatol. 71 suppl 10:L05 https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-tolerability-pharmacokinetics-andclinical-outcomes-following-single-dose-ia-administration-of-ubx0101-a-senolytic-mdm2-p53-interaction-inhibitor-in-patients-with-knee-oa/ (2019).

- 62.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, Satija R. Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:411–420. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lab, S. Seurat PBMC Tutorial, https://satijalab.org/seurat/v3.0/pbmc3k_tutorial.html

- 64.Macosko EZ, et al. Highly Parallel Genome-wide Expression Profiling of Individual Cells Using Nanoliter Droplets. Cell. 2015;161:1202–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv:1802.03426v2 [stat.ML] (2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

There are no restrictions on the availability of materials or information once the manuscript is published. All RNAseq data are available at NCBI GEO GSE152805.