Abstract

Tectonics and climate-driven surface processes govern the evolution of Earth’s surface topography. Topographic change in turn influences lithospheric deformation, but the elementary scale at which this feedback can be effective is unclear. Here we show that it operates in a single weather-driven erosion event. In 2009, typhoon Morakot delivered ~ 3 m of precipitation in southern Taiwan, causing exceptional landsliding and erosion. This event was followed by a step increase in the shallow (< 15 km depth) earthquake frequency lasting at least 2.5 years. Also, the scaling of earthquake magnitude and frequency underwent a sudden increase in the area where mass wasting was most intense. These observations suggest that the progressive removal of landslide debris by rivers from southern Taiwan has acted to increase the crustal stress rate to the extent that earthquake activity was demonstrably affected. Our study offers the first evidence of the impact of a single weather-driven erosion event on tectonics.

Subject terms: Natural hazards, Solid Earth sciences, Geodynamics, Geomorphology, Geophysics, Seismology, Tectonics

Introduction

It is well established that tectonics and climate influence the evolution of the Earth’s surface by modulating the rate and pattern of erosion and sedimentation1,2. In turn, theoretical predictions and numerical models suggest that changes of surface topography by surface processes can promote tectonic deformation over geological times3–5 (1–10 Myr), enhance fault slip over intermediate time scales6–9 (1 kyr–1 Myr), and induce sufficient static stress changes over a seismic cycle (1–1,000 year) to trigger earthquakes10. However, the influence of ongoing surface processes on tectonics has not been directly observed. Over seasonal timescales, surface (un)loading induced by rainfall or snow can modulate local to regional seismicity11,12,13. Here we ask if a single erosional event can have a discernable effect on seismogenic processes, which dominate deformation of the Earth’s upper crust. Both large-magnitude earthquakes and extreme rainfall events can trigger instantaneous and widespread landsliding, driving the export of millions of tons of sediment from mountain areas over periods of months to years2,14. At these timescales, geophysical methods allow monitoring of changes in earthquake activity associated with erosional perturbations. Compared to large-magnitude earthquakes, rainfall events do not directly trigger aftershock sequences (even if surface (un)loading can modulate seismicity), which could preclude the observation of a seismicity change induced by erosion. We therefore focus in the following on detecting seismicity changes associated with an erosional perturbation induced by a rainfall event.

Results

Landslides and erosion triggered by typhoon Morakot in Taiwan

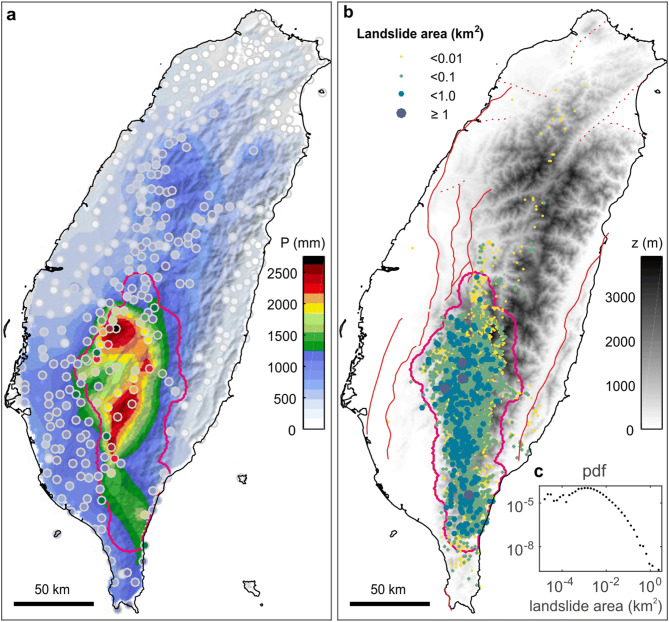

For an example of an erosional perturbation, we consider typhoon Morakot, which made landfall in Taiwan from 7 to 9 August 2009. It delivered up to 3 m of precipitation in 3 days (Fig. 1), the largest recorded rainfall event in Taiwan in the past 50 years15. The typhoon triggered more than 10.000 landslides (see “Methods” section) in mountainous southwest Taiwan, where cumulative rainfall exceeded ~ 1 m (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1). In this area of ~ 7,000 km2 (hereafter the landsliding zone), that accounts for ~ 99% of the 1.2 km3 of total landslide volume16, the landslide spatial density ranges between 4 and 22 km-2 (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S2). The equivalent average erosion induced by these landslides is ~ 17 cm, which corresponds to ~ 10–100 years of erosion at the decadal average rate2. Most triggered landslides were connected to the river network17, which has led to a sharp increase of suspended sediment export after Morakot18,19. Consistent with geomorphological observations after the 1999 Mw 7.6 Chi-Chi earthquake20, enhanced sediment removal persisted for > 2 years18,19, although export of the coarse fraction of landslide debris may take decades or more21. The exact volume of sediment export is difficult to estimate, but the landsliding zone must have undergone a progressive surface mass unloading after one of the largest weather-driven erosion events on record. Despite a very likely large uncertainty, we roughly estimate that about 20–50% of the 1.2 km3 of landslide volume was exported of the landsliding zone after typhoon Morakot over the time period 2009–2012 (see “Methods” section).

Figure 1.

Morakot-driven rainfall and landslides in Taiwan. (a) Hillshaded map of cumulative rainfall during typhoon Morakot (7–9 August 2009), obtained by interpolation of data from local weather stations (colored dots). (b) Digital elevation model of Taiwan with location of mapped landslides triggered by typhoon Morakot. Circle size and color indicate the surface area of a landslide, while the magenta line delimits the area with highest spatial density of landslides (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S2), referred to as the landsliding zone. Solid and dashed red lines indicate active thrust and strike-slip or normal faults, respectively22. Other less well identified faults exist inside the range27. (c) Probability density distribution of the surface area of landslides triggered by typhoon Morakot for areas greater than 10 m2. Maps were performed using Matlab R2019b.

The landsliding zone belongs to a tectonically active region and is bounded in the east and west by several identified active thrust faults22. Thrust faults located in the western foothills have a dip angle between 10° and 30° and merge at depth, probably around ~ 10–15 km, into a basal decollement beneath the range22,23. In the east, the Longitudinal Valley fault has a dip angle ~ 45°–60°. Together, these faults accommodate ~ 40 mm year−1 of shortening, which is about half of the total convergence rate across the Taiwan plate boundary24. In addition, less well constrained faults are located beneath the range, as testified by the frequent seismicity observed in Central Taiwan.

Temporal changes in seismicity after Morakot

To determine how the erosional unloading due to typhoon Morakot may have impacted fault dynamics, we analyze the evolution of shallow (< 15 km) seismicity in Taiwan after it made landfall. Because the expected stress change is small compared to background tectonic loading at seismogenic depth10, we focus on detecting changes in the statistics of recorded seismicity, such as the earthquake frequency, seismic moment rate and the b-value of the Gutenberg–Richter earthquake size distribution (see “Methods” section), rather than on individual events. We use the seismicity catalogue of the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan, which includes > 340,000 earthquakes during the period 1995–2015 over Taiwan island.

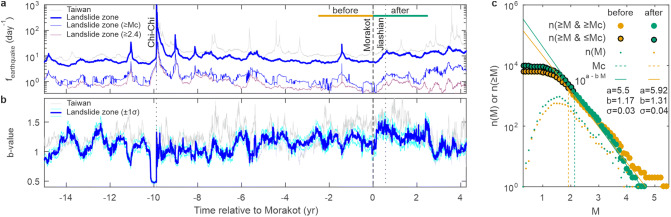

First, we assess the time evolution of earthquake statistics using a temporal sliding window of 1,001 earthquakes (see “Methods” section). Results show a stepwise increase of the frequency of shallow (< 15 km) earthquakes in the landsliding zone after Morakot (Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S3). Although this frequency increase is orders of magnitude lower than after the Chi-Chi earthquake, it is observed both for earthquakes with magnitude above the completeness magnitude (from ~ 0.8 to ~ 2 earthquakes per day) and for all recorded earthquakes (from ~ 5 to ~ 10 earthquakes per day). The increase of earthquake frequency during the 2.5 year after Morakot has a probability of 1 (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S4). The probability is still significant, at the 95% confidence interval, when considering a frequency increase by a factor ~ 1.2–1.5. Except for the regional seismicity rate increases due to the Chi-Chi earthquake, this is the only significant increase in earthquake frequency, over a period of 2.5 year, observed over the investigated period (1994–2013).

Figure 2.

Time evolution of seismicity in Taiwan relative to typhoon Morakot. (a) Time evolution of frequency of shallow (< 15 km) earthquakes. The thick and thin blue line indicates the frequency of all earthquakes and of earthquakes greater than the completeness magnitude, respectively, inside the landsliding zone. The magenta line indicates the frequency of earthquakes inside the landsliding zone with a magnitude greater than a conservative value of 2.4 for the completeness magnitude. The thin grey line indicates the frequency of all earthquakes outside the landsliding zone. (b) Time evolution of the b-value of the Gutenberg-Richter law inside (heavy blue line) and outside (light grey line) the landsliding zone (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S1). (c) Gutenberg-Richter law fits over the distributions of cumulative earthquake numbers in the landsliding zone as a function of earthquake magnitude during the 2.5 years before (yellow) and after (green) typhoon Morakot (see “Methods” section).

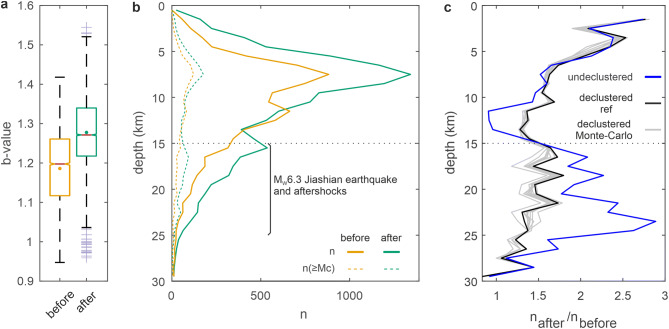

Moreover, the increase in earthquake frequency after Morakot is associated with an increase in the b-value from 1.18 ± 0.1 to 1.28 ± 0.1 (Fig. 3a). Both increases have a step-like shape, which lasts for at least 2.5 years (Supplementary Figs. S5, S6) and do not follow an Omori-type inverse law, which describes the temporal evolution of aftershock sequences. Because the seismometer network used to detect earthquakes remained similar in the time period January 2007 to December 2011 (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S7), we restrict our comparison to the time period from 2.5 years before to 2.5 years after Morakot. More instruments were added, mainly in North Taiwan, at the beginning of 2012, which explain why the frequency of earthquakes remains high in the landsliding zone after 2012, despite a decrease of the b-value towards its pre-Morakot value. Using a conservative and constant value for the completeness magnitude of 2.4 (see Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S3), we observed that earthquake frequency decreases to pre-Morakot values after about 2.5. The increase of the b-value in the landsliding zone after Morakot is found for different fitting methods of the Gutenberg-Richter law and sampling methods associated with the sliding time window (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Figs. S5, S6) and therefore deemed robust.

Figure 3.

Change in b-value and depth of earthquakes after typhoon Morakot. (a) Notched whisker plots of b-value estimates for 2.5 years before (yellow) and after (green) typhoon Morakot inside the landsliding zone show the median (red line), mean (dot), 25th and 75th percentiles (box limits), whisker lengths (dashed lines) and outliers (purple crosses) of the b-value. Notches display the variability of the median between samples. (b) Histograms of earthquake depth during the 2.5 years before (yellow) and after (green) typhoon Morakot in the landsliding zone. Solid and dashed lines indicate depth-distribution for earthquakes of all magnitudes and magnitudes greater than the completeness magnitude, respectively. (c) Depth distribution of the ratio of the number of earthquakes in the 2.5 years after typhon Morakot, nafter, over the number of earthquakes in the 2.5 years before, nbefore. The blue line indicates results considering all earthquakes, the black line indicates results considering the reference declustered catalog and the grey lines indicate results obtained using the 50 declustered catalogues, resulting from a Monte-Carlo sampling of the model parameter space (see “Methods” section).

In addition, considering all earthquakes during the 2.5 years before and after Morakot gives b-value estimates of 1.17 ± 0.03 and 1.31 ± 0.04 (Fig. 2c), respectively, similar to the values obtained by averaging the temporal b-value signal (Fig. 3a). We observe that the increase in earthquake frequency and b-value in the landsliding zone after Morakot coincides with an increase in the number of shallow earthquakes at depths < 15 km (Fig. 3b,c). Moreover, the increase is more pronounced closer to the surface and reaches a factor 2 to 3 in between 0 and 5 km of depth. We also observe a secondary peak at greater depth, 15 to 25 km. However, the rate of seismic moment release remains low after typhoon Morakot, and potentially lower than before (Supplementary Fig. S3). Crucially, earthquakes outside the landsliding zone do not show a significant temporal increase of both their frequency and b-value after Morakot.

Seismicity changes are not associated to earthquake clustering

These temporal changes in earthquake statistics after Morakot are determined from an undeclustered earthquake catalog. However, using a declustered catalog (see “Methods” section) also leads to similar changes in earthquake frequency and in its associated probability, b-value and depth-distribution after Morakot (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. S9, S10). Moreover, this result is not limited to a single parametrization of the declustering algorithm and appears robust for all the acceptable combinations of declustering parameters. For instance, the increase in the number of earthquakes after Morakot at 15 to 25 km of depths is fully removed when considering any of the resulting declustered catalog, while the shallow peak remains (Fig. 3c). This demonstrates that these seismicity changes at shallow depths are not associated with triggering processes by large mainshocks, or by other earthquakes. In addition, based on comparisons between the observed earthquake catalog and synthetic catalogs that share the same average properties, we demonstrate that the observed changes in earthquake frequency and b-value after Morakot, in the landsliding zone, depart statistically from random temporal changes (Supplementary Fig. S12).

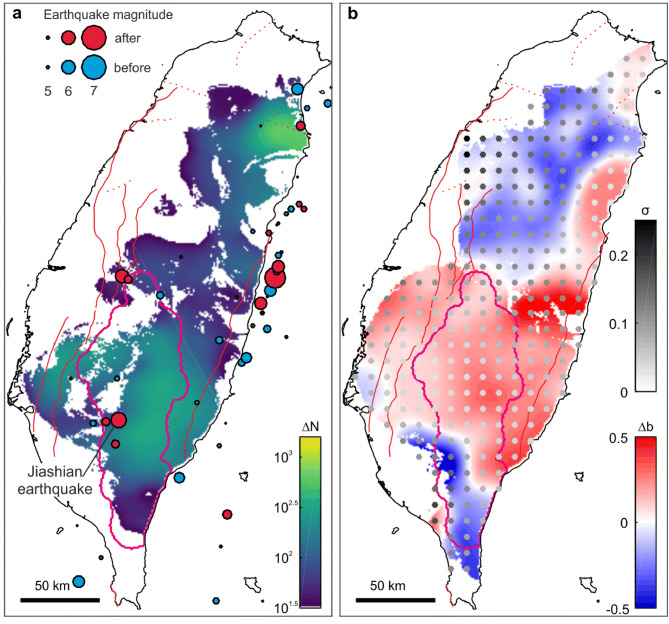

Spatial changes in seismicity after Morakot

To assess how the chosen delimited area affects our results, we compute the change in the spatial pattern of the frequency and b-value of shallow (< 15 km) earthquakes from before to after Morakot. For this, we use a sliding window in space with a radius of 30 km, which allows us to detect large-scale features not affected by small sub-samples of events (see “Methods” section). It is applied separately to earthquakes in the 2.5 years before and after Morakot, respectively. Consistent with the temporal evolution of earthquake frequency, results show an increase in the number of earthquakes after the typhoon over the landsliding zone (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S8). This increase is observed for earthquakes with magnitudes above the completeness magnitude and also for all recorded earthquakes. It is not limited to the vicinity of the landsliding zone, but it also occurred in northeast Taiwan. However, outside the landsliding zone, increases in the b-value appear not to be associated to increases in the number of earthquakes. For instance, North-East Taiwan displays a significant increase in the number of earthquakes associated to a decrease of the b-value. We note that the spatial correlation between earthquake statistics change and the landsliding zone is less well resolved and less robust (see “Methods” section) than the temporal correlation.

Figure 4.

Changes in seismicity after typhoon Morakot. (a) Map of difference of shallow (< 15 km) earthquake numbers, , during the 2.5 years after and before typhoon Morakot. Only earthquakes greater than the completeness magnitude were considered. For readability, values lower than 101.5 are shown in white. Red and blue circles locate earthquakes greater than magnitude 5 after and before typhoon Morakot, respectively. (b) Change in b-value, (red-blue colormap), and uncertainty, σ (gray circles) of b-value estimates (see “Methods” section, Supplementary Fig. S3). Maps were performed using Matlab R2019b.

Discussion

Previous intense erosional events associated with the Chi-Chi earthquake (1999), and typhoons Herb (1996) and Toraji (2001) did not induce any detectable change of seismicity. This may be because these events had less erosion, the total volume of ~ 0.45 km3 of landslides triggered by Chi-Chi earthquake25 being by far the largest, and because most landslides triggered by these events deposited debris distant from rivers14. Besides, the high rate of aftershocks after Chi-Chi prevents detection of a change in earthquake frequency or b-value associated with erosion due to Chi-Chi or Toraji, if there was any. We also note that the changes in earthquake frequency and b-value are not perfectly synchronous with typhoon Morakot and occur about 1–2 months after the typhoon. However, the time resolution of our temporal analysis does not allow us to detect with confidence changes occurring with a period less than about 100 days (see Supplementary Fig. S5b). The duration of the transient increase in earthquake frequency and b-value occurring after typhoon Morakot lasts about 2.5 years.

Non-erosional causes of the observed changes in earthquake statistics in SW Taiwan are possible but appear less likely. Earthquakes result from the stresses induced by tectonics, in general, but also by other earthquakes26. The 4th of March 2010, the Mw 6.3 Jiashian earthquake occurred within the landsliding zone, close to its western limit, and was followed by many aftershocks. However, this earthquake and most aftershocks are located at 15–25 km depth (Supplementary Fig. S11), as shown by seismological records27 and further confirmed by the declustering process, which mostly removes events below 15 km depth, (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S10). Therefore, the Jiashian earthquake does not affect shallow earthquake statistics and cannot be considered responsible for the increase of the b-value after Morakot (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Hydrological triggering of seismicity after the heavy rainfall during typhoon Morakot, either by surface loading or by pore pressure diffusion28, could be an alternative mechanism. Indeed, on the east coast of Taiwan, where landslide erosion was limited, borehole water levels rose by 4 m after typhoon Morakot, and a volumetric contractional strain was observed29,30. However, both signals decayed in ~ 6 months and their amplitudes and temporal evolutions do not depart from the mean seasonal trends observed from 2006 to 2011. Moreover, pore pressure diffusion along permeable faults after large rainfall events generally leads to episodic increases of seismicity31 and not to prolonged changes as observed in our case.

The temporal and spatial collocation of intense landsliding triggered by typhoon Morakot and the observed increase of shallow earthquake frequency and b-value suggest a potential mechanistic link. Direct physical modeling of the impact of erosion during and after Morakot on seismicity is beyond our reach because the location, magnitude and rate of sediment export from the landsliding zone are not reliably constrained. Despite this, simple elastic models show that large erosional events with rapid sediment export can induce static stresses at depth, sufficient to modulate tectonic stresses on the shallower (< 5–10 km) parts of faults10. Removing 20 to 50% of the landslide volume in 2.5 years, equivalent to about 2 to 5 cm of average erosion over the landsliding zone, would lead to a Coulomb stress increment on a nearby thrust fault of about 0.1 10–1 to 0.25 10–1 bar at 5 km depth10, using a thrust dip angle of 30° and an effective friction of 0.6. These stress increments are roughly similar to the ones induced by seasonal hydrologic loading in the Himalaya, ~ 0.2–0.4 × 10–1 bar, which are suggested to lead to a seasonal modulation of earthquake frequency32.

In addition, spring-slider models33 and 2D elasto-dynamic models of seismogenic faults34 with rate-and-state friction laws35,36 show that the rate of seismicity can increase linearly or more than linearly due to a positive, step-like stress perturbation. It is also observed that shallow earthquakes generally have smaller magnitudes and larger b-values than deeper earthquakes37 possibly because they nucleate at lower differential stresses38. Our observations suggest that the intense and prolonged sediment export and surface unloading after typhoon Morakot could have acted as a progressive increase of stresses, with a complex spatio-temporal evolution, on the shallow parts of underlying thrust faults10, giving rise to a similar increase of shallow earthquake frequency and b-value in Southwest Taiwan.

The proposed erosional-driven mechanism to explain the changes in seismicity after Morakot offers new perspectives on the links between climate, erosion and tectonics4,5 at the time scale of elementary processes. While numerous studies have shown that earthquakes and storms can trigger landslides2,14,20,25, this is to our knowledge the first potential evidence of the short-term and ongoing influence of erosion on seismicity. Because the mechanical link between erosion and stresses is through crustal elasticity10, crustal deformation is sensitive not only to extreme weather-driven erosion but also to the cumulative effects of smaller but numerous erosion events. More frequent extreme rainfall, for instance under a warmer climate39, could result in accelerated sediment transport19 and in turn in changes in the rate of shallow earthquakes, similar to the modulation of seismicity by surface water load variations13. Over the duration of the transient increase in seismicity, the shallow but small-magnitude seismicity induced by erosion is not likely to trigger new landslides, and the seismic moment rate would not be significantly affected. Hence, we do not expect a significant feedback of this additional deformation on erosion. However, the impact of this short-term transient signal on the seismicity and erosion over longer time scales, such as the duration of a seismic cycle, remains to be investigated. Our results therefore call for a new generation of process-based models coupling landscape dynamics21 and fault dynamics34 at scales relevant to natural hazards and societal issues. In these models, storms, floods, mass wasting, river sediment transport, redistribution of water, elastic stress transfer, seismicity and seismic wave propagation should all be represented to account for the complexity of the links between climate, erosion and tectonics.

Methods

Morakot rainfall data

The map of cumulative rainfall during Morakot was obtained by natural-neighbor interpolation of cumulative hourly rain gauge measurements over the period 7 to 9th of August 2009. Data from 377 stations across Taiwan were used from the Data Bank for Atmospheric Research at the Taiwan Typhoon and Floods Research Institute.

Morakot landslide catalogue

Mapped landslides were delineated manually by comparing surface reflectivity and morphology on pre- and post-event FORMOSAT-2 satellite images40 (2 m panchromatic and 8 m multi-spectral). To cover most of the islands we mosaicked multiple cloud-free pre-event (01/14, 05/08, 05/09, 05/10, 06/06) and post-event (08/17, 08/19, 08/21, 08/28, 08/30, 09/06) images taken in 2009. For parts of the inventory, especially east of the main divide, landslides were first mapped automatically and then edited manually. For both approaches, the scar, runout and deposit areas are not differentiated. We did not consider debris flow transport areas and excluded gentle slopes (< 20°) from mapping to avoid confusion with human activity. Special attention was given to the separation of individual landslides, which had common transport or deposit areas but independent initiation points41. The robust and conservative estimation of landslide surface area is especially important for the estimation of landslide volume42.

Estimation of landslide volume

The landslide volume was estimated based on landslide area, following the method of ref. 16 and 41. Briefly, we assumed constant size ratios between scar and deposit areas of 1.1 and 1.9 for mixed and bedrock landslides, respectively42. Then, we converted the scar area into volume using a power law with different prefactor () and exponent () for mixed and bedrock landslides, with and for m2 and and for m2, respectively41. Recent studies have proposed a regional scaling relationship for southern Taiwan, based on measurement of large landslides caused by typhoon Morakot43. With these parameters (, ), and without scar correction, we obtain volumes ~ 3 times larger for intermediate size (mixed) landslides and twice smaller volume for very large (bedrock) landslides. Overall, this would not change the order of magnitude of erosion nor the results discussed in this study. Distributing uniformly the total volume, ~ 1.2 km3, of landslides triggered by typhoon Morakot over the area of the landsliding zone, ~ 7,000 km2 , gives about 17 cm of thickness of mobilized sediments.

Estimation of sediment export after typhoon Morakot

There is currently no method allowing a robust and accurate measurement of sediment transport after typhoon Morakot, including suspended and bed loads, at the scale of Taiwan. Concerning suspended load, about 0.75 GT of sediments have been exported away in 2009 from the Gaoping catchment compared to an average ~ 0.02 GT/year over the period 1950–2008 (ref.19). Most of the 0.75 GT of sediment export in 2009 from the Gaoping catchment, which drains a large area of the west part of the landsliding zone, can therefore be attributed to the impact of the landslides triggered by Morakot. Similarly, over the Island of Taiwan, suspended sediment discharge increased from about a mean of ~ 0.38 GT/year to ~ 1.1 GT/year in 2009, and a large part of this increase can be attributed to the impact of Morakot19. In 2010, suspended sediment discharge decreases to pre-Morakot values, partly due to the absence of large water discharge events. Timescales for bedload sediment export is probably much larger, between a few years to decades21 and potentially centuries. Most rivers connected to the landsliding zone experienced rapid and intense sediment aggradation, with 10–100 m of sediment thickness, in response to Morakot typhoon. To our knowledge, no study has been published on the regional evolution of this bedload sediment mass. The estimated total volume 1.2 km3 of landslides triggered by Morakot could translate in about 2.5–3 GT of sediments. It is therefore likely that about 20–30% of this mass was removed by suspended transport in 2009, and probably a few percent or more in the following years. Therefore, a rough estimate could lead to possibly 20–40% of sediment export over the time period 2009–2012. Adding bedload transport could hypothetically increases this estimate to 20–50% for the time period 2009–2012.

Earthquake catalogue of Taiwan

We extracted earthquakes at shallow depths (< 15 km) from the earthquake catalogue of the Taiwan Central Weather Bureau44 for the period 1995–2015 over the emergent part of Taiwan. This catalogue is accessible through the Taiwan Central Weather Bureau (https://gdms.cwb.gov.tw). The monitoring network includes short-period and broadband seismographic systems stations. The location and number of seismic stations changed during the period 1995–2015. The configuration of the seismic network in the south of Taiwan and in the landsliding zone remained relatively similar over the period January 2007 to December 2012 (see Supplementary Fig. S8), but after 2012, 2.5 years after Morakot, the number of stations was increased mostly in North Taiwan. This has caused a decrease of the measured completeness magnitude over all of Taiwan, including in the landsliding zone (see Supplementary Fig. S2). We therefore do not focus our analysis on changes in the frequency of earthquakes occurring after 2.5 years after Morakot (beginning of 2012). Yet, we note that using a constant and conservative value for the completeness magnitude of 2.4 (see Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. S3), we observed that earthquake frequency decreases to pre-Morakot values after about 2.5 years.

Characterization of earthquake size distribution

The Gutenberg–Richter distribution is classically used to characterize the relation of the number of earthquakes above a given magnitude, , to the magnitude , where a and b are parameters related to the number of earthquakes and to the slope of the relationship, respectively. This relationship is appropriate only for magnitudes above the completeness magnitude, , of the catalogue. is determined by a modified version of the simple but robust maximum curvature method45, where is equal to the maximum of the first derivative of the frequency-magnitude curve, plus 0.5. We compute a maximum likelihood estimate46 of the b-value, and of its uncertainty, , where is the mean magnitude of the considered earthquakes with . Note that the number of earthquakes considered has a strong control on the b-value estimate and its uncertainty47, and that only relative spatial or temporal changes of the b-value should be interpreted.

Time evolution of earthquake statistical properties

We use a temporal sliding window to subsample the earthquake catalogue and to assess time variations of earthquake statistical properties. Because the uncertainty of the b-value strongly depends on the number of considered events, and because larger samples give better estimates, we use a sliding window of 1,001 events to prevent undue statistical bias. The window is centred on a given earthquake and the corresponding b-value and earthquake frequency are determined for the 500 earthquakes that occurred immediately before and immediately after this event. Earthquake frequency is computed by dividing by the temporal length of the sliding window. Among the 1,001 earthquakes, only those with magnitude above are used to estimate the b-value. We assess the effect of changing the sampling method of the temporal window, by considering an a priori value of , and considering a fixed number of earthquakes with a magnitude ranging from 101 to 1,001 (Supplementary Figs. S5, S6). We find a consistent increase of b-value in the 2.5 years after Morakot for ranging from 101 to 501, as all these earthquakes occurred within a time window duration lower than 2.5 years. For or 1,001 the window duration is equal to or greater than 2.5 years (about 3 years for 1,001), which leads to over-smoothing of the signal, and prevents detection of changes occurring on shorter time-scales. It is also notable that changing the fitting method from maximum likelihood to least-square, which is generally considered less reliable, does not significantly change the relative variation of the b-value in time (Supplementary Fig. S5). This includes the changes occurring after Morakot.

Probability of earthquake frequency change with time

Following ref.48, we compute the probability P that the earthquake frequency increases by a factor greater than r between a period 1 and 2,

where is the incomplete Gamma function, is the number of earthquake over a certain period and is the earthquake frequency. The subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the time periods 1 and 2. We first apply this approach to determine the probability of earthquake frequency change between the 2.5 year before and after Morakot, in the landsliding zone considering only earthquakes with a depth shallower than 15 km (Supplementary Fig. S4a). We find a probability 1 for an increase of earthquake frequency (i.e. with ), when considering all the earthquakes or only earthquakes above the completeness magnitude. The 90% confidence interval, , of an earthquake frequency change is found for , when considering only the earthquakes above the completeness magnitude, and for all magnitudes. This demonstrates that the change of earthquake frequency after Morakot is significant with a ratio of 1.23, at least. We then apply the same analysis to the entire catalog by using a double sliding window of period 2.5 years after and before the center time (Supplementary Fig. S4b). The largest increase in earthquake frequency, with a factor close to 5 for a probability inside the confidence interval, is Chi-chi earthquake. Except for Chi-Chi, the time period including typhoon Morakot and Jiashian earthquakeis the only one associated with a significant and positive change of earthquake frequency over a period of 2.5 years since 1994. However, as demonstrated in this manuscript, Jiashian earthquake did not lead to a significant increase in the number of earthquakes at shallow depths (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs. S9, S10, S11, S13).

Spatial variations of earthquake statistical properties

We use a common spatial sliding window to subsample the earthquake catalogue and to assess variations of earthquake statistical properties in space49 between the 2.5 years before and after typhoon Morakot. We use a radius of 30 km for the sliding window, which enables sampling of a sufficiently large number of earthquakes at a length scale that is smaller than that of the landslide zone of 7,000 km2. The sampling window effectively corresponds to a disk shape extending to a depth of 15 km. The b-value is determined for the recorded earthquakes in each disk volume by maximum likelihood estimation. This method has an inherent statistical bias as the number of sampled earthquakes changes significantly depending on the local rate of seismicity. The minimum number of events for the determination of the b-value is set arbitrarily at 50. Our method can give rise to small-scale shapes in the maps of b-value, such as disk and rod shapes, that are not the focus of this study. We use a disk shape kernel with a radius of 15 km, convolved with the initial b-value map to blur the mapped patterns and to isolate features with longer wavelengths. More sophisticated methods exist to compute spatial variations of b-value, including a penalized likelihood-based method50 and a distance-dependent sampling algorithm51.

Declustering and seismicity changes after Morakot

Several studies investigating potential earthquake frequency changes use declustered earthquake catalogs. However, declustering is an ill-posed problem that does not have a unique solution52 and that will lead to method-dependent results. Yet, to test the impact of potential earthquake clustering on our results, we have applied the traditional Reasenberg declustering algorithm53, obtained from the ZMAP toolbox54, to the CWB earthquake catalog. This deterministic algorithm aims to remove earthquake sequences, defined as chains of connected earthquakes in space and time, leaving only the initial earthquake in a given sequence. We use standard parameters52 adapted for Taiwan with day the minimum look-ahead time for for building clusters when the first event is not clustered, days, the maximum look-ahead time for building clusters, , a confidence probability, , the effective lower cutoff magnitude chosen here to be consistent with the CWB catalog, , the increase in lower cutoff magnitude during clusters, and , the number of crack radii surrounding each earthquake within new events considered to be part of the cluster. We emphasize here that declustering has been performed over the entire catalog, without any regional selection of the seismicity (i.e. not only in the landsliding zone and not only above 15 km of depth), to prevent potential declustering biases associated to earthquake censoring.

Supplementary Figure S9 shows the influence of declustering on earthquake frequency, b-value, depth distribution and the probability of earthquake frequency change after Morakot in the landsliding zone (< 15 km depth). We observe that declustering mainly leads to a decrease of earthquake frequency over the 2.5 years before typhoon Morakot, and to very minor changes after. We find that declustering even slightly enhances the probability of an increase in earthquake frequency after Morakot. In addition, declustering does not significantly changes the time variation in b-value nor the depth-distribution of seismicity. We note that the Reasenberg declustering approach is well-suited to remove earthquake sequences that lead to significant changes (e.g. an aftershock sequence after a large mainshock) and not to identify potential triggered events during quiet periods associated with a constant and low frequency of earthquakes48. Under this potential limitation, this analysis demonstrates that earthquake clustering is not the reason for the observed changes after typhoon Morakot.

In addition, we are confident that large and deep mainshocks occurring in the landsliding zone, below 15 km, such as Mw 6.3 Jiashian earthquake in 2010, are not the cause for the observed seismicity changes. Indeed, declustering is efficient to remove most of the aftershocks caused by the Jiashian earthquake, which appear to be concentrated at depth between 15 and 30 km (Supplementary Fig. S10). To confirm this inference, we vary the values of the declustering parameters using a range of acceptable values around the reference values48,55: days, days, , and . We use a random sampling of the parameters space within these ranges, using a Monte-Carlo approach, to define 50 declustering parameter combinations. We obtain similar results, in terms of earthquake depth-distribution (Supplementary Fig. S9) and temporal variations of earthquake frequency (Supplementary Fig. S10) as in the reference declustering model. This confirms the robustness of the observed changes in shallow seismicity after Morakot that are not related to earthquake interactions.

Seismicity temporal variation: random hypothesis versus significant regional seismicity change versus local earthquake interactions

Having a declustered catalog should theoretically imply that all the earthquakes are seismically independent from each other. In turn, earthquakes should be randomly distributed in time, unless a non-seismic process triggers them. Here we test this hypothesis by comparing the observed changes, in earthquake frequency and b-value after Morakot, obtained from the “true” declustered catalog with those from 200 “synthetic” earthquake catalogs over the period 2006–2015. Each synthetic catalog is generated using the exact same earthquakes as in the true declustered catalog, including their magnitudes, but the time of occurrence of each earthquake is randomly sampled over the period of interest (2006–2015) using a time step of 1 s. It results that each synthetic catalog has the exact same magnitude distribution and average earthquake frequency than the true one, but the temporal distribution of earthquakes is randomly distributed. For each catalog (true or synthetic), the probability of frequency change and the change in b-value after Morakot are computed by comparing the earthquakes occurring in the 2.5 years after and before Morakot (see Supplementary Fig. S12). The probability of a frequency change after Morakot for all the synthetic catalogs drops around a ratio 0.8–1.2, centered around 1, meaning there is no significant frequency change. This clearly departs from the frequency change observed using the true catalog that drops around a ratio of 1.3–1.6. In addition, the change in b-value of the true catalog is significantly greater than the changes of all the synthetic catalogs. Overall, these results mean that both the frequency change and the b-value increase after Morakot are robust features, that depart from random changes. In addition, because we performed these tests using the declustered catalog, which should only include independent earthquakes, this means that these robust and non-random changes should not be associated to the occurrence of large mainshocks. We also note that potential earthquake interactions in a local subset of the landsliding zone56 cannot explain the increase in earthquake frequency after Morakot (Supplementary Fig. S13).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

P.S. and L.J. acknowledge funding by Université Rennes 1 and by Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR) through the EROQUAKE project (ANR-14-CE33-0005). We are grateful for support by the France-Taiwan International Associate Laboratory “From Deep Earth to Extreme Events”, and thank the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan and the Taiwan Typhoon and Floods Research Institute for access to their data. We thank Edwin Baynes, Thomas Croissant, Dimitri Lague and Harsha Bhat for discussions. We also thank Roland Burgmann, Ya-Ju Hsu and several anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the current version of this manuscript and on previous ones. This study contributes to the IdEx Université de Paris ANR-18-IDEX-0001. This is IPGP contribution 4145.

Author contributions

P.S. initiated this project, analyzed the data and led the writing of the paper. L.J. and N.C. helped with the mechanical and statistical interpretation of the earthquake catalog that was partly analyzed and provided by W.-T.L. and T.T., O.M., P.M. and N.H. checked and completed the landslide catalog that was provided by S.-H.C. N.H. suggested investigation of the impact of typhoon Morakot. M.S., R.C., J.B.H.S. and M.M. contributed to the design of this study. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are provided along with the manuscript. The earthquake catalogue is also accessible through the Taiwan Central Weather Bureau (https://gdms.cwb.gov.tw). The rainfall data is also accessible through Data Bank for Atmospheric Research at the Taiwan Typhoon and Floods Research Institute (https://www.narlabs.org.tw/en). The landslide dataset is also available by request to O.M., P.M. and N.H.

Code availability

The Matlab code used to perform the analysis and the figures of this manuscript, as well as the data needed to process the figures of this paper, are provided here: https://zenodo.org/record/3778355. The Reasenberg declustering algorithm is accessible through the ZMAP set of tools (https://www.seismo.ethz.ch/en/research-and-teaching/products-software/software/ZMAP/ and https://github.com/CelsoReyes/zmap7).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-67865-y.

References

- 1.Molnar P, England P. Late Cenozoic uplift of mountain ranges and global climate change: Chicken or egg? Nature. 1990;346:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dadson SJ, et al. Links between erosion, runoff variability and seismicity in the Taiwan orogen. Nature. 2003;426:648–651. doi: 10.1038/nature02150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlen FA, Suppe J. Mechanics, growth, and erosion of mountain belts. Geol. Soc. Am. Special Pap. 1988;218:161–178. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willett SD. Orogeny and orography: The effects of erosion on the structure of mountain belts. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1999;104:28957–28981. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whipple KX. The influence of climate on the tectonic evolution of mountain belts. Nat. Geosci. 2009;2:97–104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cattin R, Avouac JP. Modeling mountain building and the seismic cycle in the Himalaya of Nepal. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2000;105:13389–13407. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calais E, Freed AM, Van Arsdale R, Stein S. Triggering of new Madrid seismicity by late-Pleistocene erosion. Nature. 2010;466:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature09258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernant P, et al. Erosion-induced isostatic rebound triggers extension in low convergent mountain ranges. Geology. 2013;41:467–470. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maniatis G, Kurfeß D, Hampel A, Heidbach O. Slip acceleration on normal faults due to erosion and sedimentation—Results from a new three-dimensional numerical model coupling tectonics and landscape evolution. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009;284(3):570–582. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steer P, Simoes M, Cattin R, Shyu JBH. Erosion influences the seismicity of active thrust faults. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–7. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heki K. Snow load and seasonal variation of earthquake occurrence in Japan. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2003;207(1–4):159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettinelli P, Avouac JP, Flouzat M, Bollinger L, Ramillien G, Rajaure S, Sapkota S. Seasonal variations of seismicity and geodetic strain in the Himalaya induced by surface hydrology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008;266(3–4):332–344. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson CW, Fu Y, Bürgmann R. Seasonal water storage, stress modulation, and California seismicity. Science. 2017;356(6343):1161–1164. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadson SJ, et al. Earthquake-triggered increase in sediment delivery from an active mountain belt. Geology. 2004;32:733–736. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien FC, Kuo HC. On the extreme rainfall of Typhoon Morakot. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011 doi: 10.1029/2010JD015092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marc O, Stumpf A, Malet JP, Gosset M, Uchida T, Chiang SH. Initial insights from a global database of rainfall-induced landslide inventories: The weak influence of slope and strong influence of total storm rainfall. Earth Surf. Dyn. 2018;6(4):903–922. [Google Scholar]

- 17.West AJ, et al. Mobilization and transport of coarse woody debris to the oceans triggered by an extreme tropical storm. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011;56:77–85. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang MYF, Montgomery DR. Altered regional sediment transport regime after a large typhoon, southern Taiwan. Geology. 2013;41:1223–1226. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee TY, et al. Magnified sediment export of small mountainous rivers in Taiwan: Chain reactions from increased rainfall intensity under global warming. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138283. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hovius N, et al. Prolonged seismically induced erosion and the mass balance of a large earthquake. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2011;304:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croissant T, Lague D, Steer P, Davy P. Rapid post-seismic landslide evacuation boosted by dynamic river width. Nat. Geosci. 2017;10:680. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shyu JBH, Sieh K, Chen YG, Liu CS. Neotectonic architecture of Taiwan and its implications for future large earthquakes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2005 doi: 10.1029/2004JB003251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown D, Alvarez-Marron J, Schimmel M, Wu YM, Camanni G. The structure and kinematics of the central Taiwan mountain belt derived from geological and seismicity data. Tectonics. 2012 doi: 10.1029/2012TC003156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoes M, Avouac JP. Investigating the kinematics of mountain building in Taiwan from the spatiotemporal evolution of the foreland basin and western foothills. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2006 doi: 10.1029/2005JB004209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marc O, Hovius N, Meunier P, Gorum T, Uchida T. A seismologically consistent expression for the total area and volume of earthquake-triggered landsliding. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2016;121:640–663. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein RS. The role of stress transfer in earthquake occurrence. Nature. 1999;402:605–609. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu YJ, Yu SB, Kuo LC, Tsai YC, Chen HY. Coseismic deformation of the 2010 Jiashian, Taiwan earthquake and implications for fault activities in southwestern Taiwan. Tectonophysics. 2011;502:328–335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roeloffs EA. Fault stability changes induced beneath a reservoir with cyclic variations in water level. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1988;93:2107–2124. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsu YJ, et al. Revisiting borehole strain, typhoons, and slow earthquakes using quantitative estimates of precipitation-induced strain changes. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2015;120:4556–4571. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mouyen M, Canitano A, Chao BF, Hsu YJ, Steer P, Longuevergne L, Boy JP. Typhoon-induced ground deformation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017 doi: 10.1002/2017GL075615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hainzl S, Kraft T, Wassermann J, Igel H, Schmedes E. Evidence for rainfall-triggered earthquake activity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006 doi: 10.1029/2006GL027642. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bettinelli P, et al. Seasonal variations of seismicity and geodetic strain in the Himalaya induced by surface hydrology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2008;266(3):332–344. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dieterich J. A constitutive law for rate of earthquake production and its application to earthquake clustering. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1994;99:2601–2618. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ader TJ, Lapusta N, Avouac JP, Ampuero JP. Response of rate-and-state seismogenic faults to harmonic shear-stress perturbations. Geophys. J. Int. 2014;144:385. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dieterich JH. Modeling of rock friction: 1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1979;84:2161–2168. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruina A. Slip instability and state variable friction laws. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1983;88:10359–10370. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori J, Abercrombie RE. Depth dependence of earthquake frequency-magnitude distributions in California: Implications for rupture initiation. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1997;102:15081–15090. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholz CH. On the stress dependence of the earthquake b value. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2015;42:1399–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu SC, Fu C, Shiu CJ, Chen JP, Wu F. Temperature dependence of global precipitation extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1029/2009GL040218. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang K, Chiang S, Chen Y, Mondini AC. Modeling the spatial occurrence of shallow landslides triggered by typhoons. Geomorphology. 2014;208:137–148. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marc O, Hovius N. Amalgamation in landslide maps: Effects and automatic detection. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015;15:723–733. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larsen IJ, Montgomery DR, Korup O. Landslide erosion controlled by hillslope material. Nat. Geosci. 2010;3:247–251. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y-C, Chang K, Chiu Y-J, Lau S-M, Lee H-Y. Quantifying rainfall controls on catchment-scale landslide erosion in Taiwan. Earth Surf. Process. Landforms. 2013;38:372–382. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin TC, Chang CH, Pu HC, Lin HW, Leu PL. The geophysical database management system in Taiwan. Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. 2013;24:11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiemer S, Wyss M. Minimum magnitude of completeness in earthquake catalogs: Examples from Alaska, the western United States, and Japan. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 2000;90:859–869. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aki K. Maximum likelihood estimate of b in the formula logN= a-bM and its confidence limits. Bull. Earthq. Res. Inst. Tokyo Univ. 1965;43:237–239. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nava FA, Márquez-Ramírez VH, Zúñiga FR, Ávila-Barrientos L, Quinteros CB. Gutenberg-Richter b-value maximum likelihood estimation and sample size. J. Seismol. 2016;21:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marsan D, Wyss M. Seismicity rate changes. Community Online Resour. Stat. Seism. Anal. 2011 doi: 10.5078/corssa-25837590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiemer S, Wyss M. Spatial and temporal variability of the b-value in seismogenic volumes: An overview. Adv. Geophys. 2002;45:259–302. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kamer Y, Hiemer S. Data-driven spatial b value estimation with applications to California seismicity: To b or not to b. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2015;120:5191–5214. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tormann T, Wiemer S, Mignan A. Systematic survey of high-resolution b value imaging along Californian faults: Inference on asperities. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 2014;119:2029–2054. [Google Scholar]

- 52.van Stiphout T, Zhuang J, Marsan D. Seismicity declustering. Community Online Resour. Stat. Seism. Anal. 2012;10:1. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reasenberg P. Second-order moment of central California seismicity, 1969–1982. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth. 1985;90(B7):5479–5495. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiemer S. A software package to analyze seismicity: ZMAP. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2001;72(3):373–382. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schorlemmer D, Gerstenberger MC. RELM testing center. Seismol. Res. Lett. 2007;78(1):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chan CH, Wu YM. A seismicity burst following the 2010 M 6.4 Jiashian earthquake–implications for short-term seismic hazards in southern Taiwan. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012;59:231–239. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are provided along with the manuscript. The earthquake catalogue is also accessible through the Taiwan Central Weather Bureau (https://gdms.cwb.gov.tw). The rainfall data is also accessible through Data Bank for Atmospheric Research at the Taiwan Typhoon and Floods Research Institute (https://www.narlabs.org.tw/en). The landslide dataset is also available by request to O.M., P.M. and N.H.

The Matlab code used to perform the analysis and the figures of this manuscript, as well as the data needed to process the figures of this paper, are provided here: https://zenodo.org/record/3778355. The Reasenberg declustering algorithm is accessible through the ZMAP set of tools (https://www.seismo.ethz.ch/en/research-and-teaching/products-software/software/ZMAP/ and https://github.com/CelsoReyes/zmap7).