Abstract

Background:

A bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repair (BEAR) procedure places an extracellular matrix implant, combined with autologous whole blood, in the gap between the torn ends of the ligament at the time of suture repair to stimulate healing. Prior studies have suggested that white blood cell (WBC) and platelet concentrations significantly affect the healing of other musculoskeletal tissues.

Purpose/Hypothesis:

The purpose of this study was to determine whether concentrations of various blood cell types placed into a bridging extracellular matrix implant at the time of ACL repair would have a significant effect on the healing ligament cross-sectional area or tissue organization (as measured by signal intensity). We hypothesized that patients with higher physiologic platelet and lower WBC counts would have improved healing of the ACL on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (higher cross-sectional area and/or lower signal intensity) 6 months after surgery.

Study Design:

Cohort study; Level of evidence, 2.

Methods:

A total of 61 patients underwent MRI at 6 months after bridge-enhanced ACL repair as part of the BEAR II trial. The normalized signal intensity and average cross-sectional area of the healing ligament were measured from a magnetic resonance stack obtained using a gradient echo sequence. The results were stratified by sex, and univariate and multivariate regression analyses determined significant correlations between blood cell concentrations on these 2 magnetic resonance parameters.

Results:

In unadjusted analyses, older age and male sex were associated with greater healing ligament cross-sectional area (P < .04) but not signal intensity (P > .15). Adjusted multivariable analyses indicated that in female patients, a higher monocyte concentration correlated with a higher ACL cross-sectional area (β = 1.01; P = .049). All other factors measured, including the physiologic concentration of platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, basophils, and immunoglobulin against bovine gelatin, were not significantly associated with either magnetic resonance parameter in either sex (P > .05 for all).

Conclusion:

Although older age, male sex, and monocyte concentration in female patients were associated with greater healing ligament cross-sectional area, signal intensity of the healing ligament was independent of these factors. Physiologic platelet concentration did not have any significant effect on cross-sectional area or signal intensity of the healing ACL at 6 months after bridge-enhanced ACL repair in this cohort. Given these findings, factors other than the physiologic platelet concentration and total WBC concentration may be more important in the rate and amount of ACL healing after bridge-enhanced ACL repair.

Keywords: ACL, ACL repair, MRI, signal intensity, complete blood cell count, white blood cell count

A significant amount of literature has been published in recent years on the surgical treatment of a torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). The current gold standard of surgical treatment for an ACL tear is an ACL reconstruction with tendon graft. Although ACL reconstruction is usually successful in restoring stability of the knee joint, it does not reduce the risk for posttraumatic osteoarthritis.38–40,44,57 Alternatively, traditional suture repair of a torn ACL results in a high failure rate and increased knee laxity postoperatively.29,32,51 Additional studies have suggested that these unfavorable outcomes of ACL primary repair may be due to the premature loss of a blood clot between the 2 torn ends of the ACL, as well as a lack of a bridging tissue scaffold to enhance healing.50

This biological observation has led to interest in evaluating a bridge-enhanced ACL repair (BEAR) procedure, where the suture repair is supplemented with an extracellular matrix implant saturated with autologous blood45,47 and placed in the gap between the 2 torn ACL ends at the time of surgery. The blood-laden implant provides an environment and structure to facilitate healing of the ACL. The safety and effectiveness of this procedure have been evaluated in preclinical models34,45,55,58 and in an early clinical cohort study.34,48,49 However, the effects of the concentration of specific cell types in the autologous whole blood on the size and quality of the healing ligament remain unknown.

Prior studies evaluating the use of other blood-derived products such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP), where the platelet count is enriched, typically have had a low red blood cell fraction.2,20 PRP has been shown to improve wound healing for other tissues.7,22,23,35,64 However, when evaluated for ACL repair or reconstruction in animal models, increasing the platelet count did not improve the strength of a repaired ACL or improve the mechanical properties of an ACL graft.26,41 The effect of including white blood cells (WBCs) in PRP has produced mixed results, with some studies showing that the inclusion of WBCs helps with bone and soft tissue healing1,21,25,56 and other studies showing that it impedes healing.4,6,53,63 Thus, it is of interest to evaluate the effects of both physiologic platelet and WBC concentration on the quality of the healing ACL after BEAR. In addition, because the extracellular matrix implant used for BEAR is made using bovine tissue, the effect of the preoperative level of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to bovine collagen on ligament healing was also thought to be of interest.

Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (MRI) has been a useful tool in evaluating ACL healing properties in large animal models.11–13,27,60 Structures with a higher cross-sectional area, and subsequently volume, would be indicative of a higher yield or maximum load.11,12 A lower water content in the healing ACL, as detected by lower signal intensity in sequences where fluid is bright, including T2*11,13 and proton density (PD) weighted sequences,3,60 has been shown to correlate with healing ACL tissue that has improved mechanical properties (ie, maximum load). Additionally, lower signal intensity in these fluid-sensitive sequences has been shown to relate to improved collagen alignment indicative of a more mature ligament in animal models of BEAR and ACL reconstruction.13,60 In this study, the Constructive Interference in Steady State (CISS) sequence was used as a measure of signal intensity. This sequence, as with the T2* and PD sequences, has lower signal intensity when tissues have lower fluid content (and higher collagen organization), but it also offers high spatial resolution and excellent contrast resolution.9,37 Thus, this sequence can provide a noninvasive and accurate measure of the healing ligament cross-sectional area and signal intensity.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether concentrations of various blood cell types placed into the implant at the time of ACL repair would have a significant effect on the healing ligament cross-sectional area and/or the normalized signal intensity (ie, healing tissue organization) at 6 months after BEAR. We hypothesized that patients with a higher physiologic platelet count and lower WBC count would have improved healing of the ACL (larger average cross-sectional area and/or lower normalized signal intensity) at 6 months after surgery. We also evaluated whether the level of IgG antibodies to bovine collagen had a significant effect on the same MR qualities.

Methods

Patients

Approval from our institutional review board and the US Food and Drug Administration was obtained before the start of the study. All patients and, if applicable, their legal guardian(s) granted informed consent. A total of 65 patients, ages 14 to 35 years, who presented with a complete ACL tear, were less than 45 days from injury, had closed physes, and had at least 50% of the length of their ACL attached to their tibia (as determined from a preoperative MRI scan) underwent the BEAR procedure as part of the BEAR II trial (IDE G150268, IRB No. P00021470, NCT 02664545). Patients were excluded from enrollment if they had a history of prior knee surgery, prior infection in the knee, or other risk factors that might adversely affect ligament healing (regular nicotine or tobacco use, corticosteroids in the past 6 months, chemotherapy, diabetes, inflammatory arthritis). Patients were excluded if they had a displaced bucket-handle tear of the meniscus requiring repair; however, all other meniscal injuries were included. Patients were also excluded if they had a full-thickness chondral injury, a grade 3 medial collateral ligament injury, a concurrent complete patellar dislocation, or an operative posterolateral corner injury. A total of 4 enrolled patients were excluded from analysis because of loss to follow-up (n = 1) and imaging artifacts during postoperative MRI (n = 3), leaving 61 for the current analysis. The 2-year patient reported outcomes and physical examination results of the BEAR II trial have been previously published.46

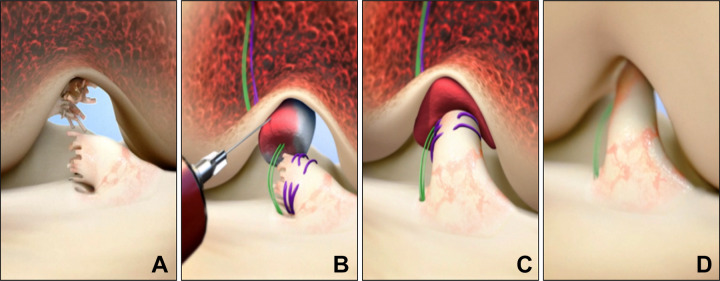

BEAR Surgical Procedure

The surgical steps for the BEAR procedure are shown in Figure 1. After the induction of general anesthesia, an examination was performed to verify a positive pivot shift on the injured side and to record the Lachman test, range of motion, and pivot-shift examination results on both knees. A knee arthroscopy was performed, and any meniscal injuries present were treated. A tibial aimer (Acufex Director Drill Guide; Smith & Nephew) was used to place a 2.4-mm guide pin through the tibia and into the tibial footprint of the ACL. The pin was overdrilled with a 4.5-mm reamer (Endoscopic Drill; Smith & Nephew). A guide pin was placed in the femoral ACL footprint, drilled through the femur, and then overdrilled with the 4.5-mm reamer. A 4-cm arthrotomy was made at the medial border of the patellar tendon, and a whipstitch of No. 2 absorbable braided suture (Vicryl) was placed into the tibial stump of the torn ACL. Alternatively, in some cases, a whipstitch was placed arthroscopically before an arthrotomy was made.

Figure 1.

Stepwise demonstration of the bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repair technique using the bridge-enhanced ACL repair (BEAR) implant. (A) In this technique, the torn ACL tissue is preserved. A whipstitch of No. 2 Vicryl (purple suture) is placed into the tibial stump of the ACL. Small tunnels (4 mm) are drilled in the femur and tibia, and an Endobutton with two No. 2 Ethibond sutures (green sutures) and the No. 2 Vicryl ACL sutures attached to it is passed through the femoral tunnel and engaged on the lateral femoral cortex. The Ethibond sutures are threaded through the implant and tibial tunnel and secured in place with an extracortical button. (B) The implant is then saturated with 5 mL of the patient’s blood, and (C) the tibial stump is pulled up into the saturated implant. (D) The ends of the torn ACL then grow into the implant, and the ligament reunites. (Reprinted with permission from Murray MM, Flutie BM, Kalish LA, et al. The bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair (BEAR) procedure: an early feasibility cohort study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(11):2325967116672176. SAGE Publishing.)

Two No. 2 nonabsorbable braided sutures (Ethibond; Ethicon) were then looped through the 2 center holes of a cortical button (Endobutton; Smith & Nephew). The free ends of a No. 2 absorbable braided suture from the tibial stump were passed through the cortical button, which was then passed through the femoral tunnel and engaged on the lateral femoral cortex. Both looped sutures of No. 2 nonabsorbable braided (4 matched ends) were then passed through the implant (BEAR implant; Boston Children’s Hospital), and 10 mL of autologous blood obtained from the antecubital vein was added to the implant. An additional 22 mL of blood was drawn and sent to the laboratory for a complete blood cell count, including a differential count of the specific types of WBCs. The implant was then passed along the sutures into the femoral notch, and the nonabsorbable braided sutures were passed through the tibial tunnel and tied over a second cortical button on the anterior tibial cortex with the knee in full extension. The remaining pair of suture ends coming through the femur were tied over the femoral cortical button to bring the ACL stump into the implant using an arthroscopic knot tying technique. The arthrotomy was closed in layers.

A standardized physical therapy protocol was followed including partial weightbearing for 2 weeks and then weightbearing as tolerated with crutches until 4 weeks postoperatively. Use of a functional ACL brace (CTi brace; Ossur) was recommended from 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively and then for cutting and pivoting sports for 2 years after surgery. Other than the brace use and initial restricted weightbearing, the patients followed a rehabilitation protocol based on that of the Multicenter Orthopaedics Outcomes Network.61,62

Outcome Measures

Blood Values

A complete blood cell count with differential was collected intraoperatively at the time of implant placement and was analyzed the same day. Samples to measure erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and bovine gelatin IgG level were obtained before surgery at the baseline visit.

MRI Assessment of ACL Healing

MRI scans were acquired from all operated knees 6 months after surgery. A 3.0-T scanner (Tim Trio; Siemens) and a 15-channel knee coil were used to obtain the following sequence: 3-dimensional (3D) CISS, 14-ms repetition time, 7-ms echo time, 35° flip angle, 16-cm field of view, and 100 × 384 × 384 slice × frequency × phase.

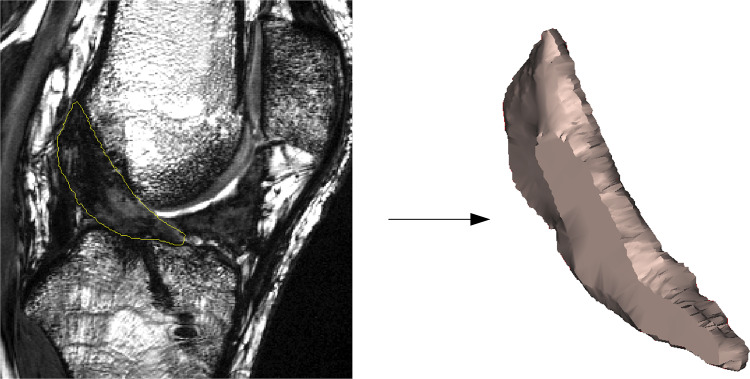

The slice thickness for the CISS sequence was 1.5 mm, and the pixel dimensions were 0.4 × 0.4 mm. The postoperative MRI scans were then used to measure the cross-sectional area and signal intensity of the healing ligament. In brief, repaired ACLs were manually segmented from the sagittal CISS image stack to create a 3D model of the structure using commercially available software (Mimics 17.0; Maternalize) (Figure 2). The model was used to measure the ligament volume and length, which were then used to calculate the average ACL cross-sectional area (volume/length).34,49 The median grayscale value of the repaired ACL was then calculated from the segmented ACL mask and normalized to the patient-specific grayscale value of the posterior cortex of the femoral shaft to minimize interscan variability. The normalized value was then reported as ACL signal intensity.34,49 The segmentations were done by an experienced examiner (A.M.K.). Both the cross-sectional area and signal intensity measurements were previously shown to be highly reproducible, with intraclass correlation coefficients of 0.959 (cross-sectional area) and 0.909 (signal intensity) when measured by 2 independent examiners.34

Figure 2.

Example of manual segmentation of the anterior cruciate ligament from magnetic resonance images.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics at baseline and surgery were summarized with descriptive statistics (mean ± SD for continuous variables, and number of cases and percentage for categorical variables). All values were checked for normality. Normally distributed data were analyzed by use of parametric tests, whereas nonparametric tests were used to analyze nonnormally distributed data. Analysis of variance was used to compare mean ACL cross-sectional area and signal intensity with bovine gelatin IgG categorized by quartiles. The mean age, body mass index (BMI), and laboratory values by sex were compared through use of the independent t test. Linear regression was used to estimate the unadjusted associations of age, BMI, and quantified blood values with healing ACL average cross-sectional area and normalized signal intensity. Because we were interested in the sex-specific influences on the biological response to ligament healing, we evaluated the effect of blood cell on each sex separately as well as adjusted models to account for the anatomic and age differences between the sexes within our population (adjusted sex-specific analysis). Analysis was done in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute), and results were considered significantly associated with outcome if P values were less than .05.

Results

Patients

Demographics and characteristics of the 61 cohort patients have previously been reported.49 The mean ± SD age of the patients was 19.3 ± 5.1 years (range, 13-35 years). The BMI was 24.7 ± 3.8 kg/m2 (range, 18.9-37.2 kg/m2). There were 25 (41.0%) male patients and 36 (59.0%) female patients; 55 (86%) of the participants identified themselves as non-Hispanic white. At the time of injury, all patients were participating in sports, and 44 (72.1%) were participating in level 1 sports.17,30,31,59 A noncontact mechanism was the cause of injury in 45 (73.8%) patients. The mean time between injury and surgery was 35.0 ± 7.9 days, with a range of 12 to 46 days.

Intraoperative Findings

All patients had a complete midsubstance tear of the ACL accompanied by a positive pivot-shift examination, with 11 (18.0%) having a glide, 40 (65.6%) having a clunk, and 10 (16.4%) classified as gross.

ACL Imaging Properties

At 6 months after surgery, the mean cross-sectional area of the healing ACL was 56.2 ± 11.8 mm2, with a range of 35.5 to 85.2 mm2. The mean normalized signal intensity of the healing ACL was 1.37 ± 0.23, with a range of 0.98 to 2.16.

Effect of Sex on Intraoperative Blood Cell Counts

The age, BMI, and blood cell values of both sexes are listed in Table 1. Male patients were significantly older in this study (P = .002) and had significantly higher BMIs (P = .011). The range of physiologic platelet concentrations measured in the female patients at surgery was 144 to 334 K cells/μL, whereas that in the male patients was 138 to 336 K cells/μL. The range of WBC concentrations measured in the female patients at surgery was 3.9 to 14.1 K cells/μL, whereas that in the male patients was 2.5 to 19.2 K cells/μL. The only significant difference in blood cell type between sexes was in measures of red blood cell quantity (hemoglobin, hematocrit, and red blood cells), where male patients had higher counts than female patients (P < .001 for all 3 comparisons). No significant difference was found in total WBC counts, platelets, ESR, or bovine gelatin IgG between sexes in this patient population (P > .05).

Table 1.

Participants’ Age, Body Mass Index, and Blood Values by Sexa

| Total (N = 61) | Male (n = 25) | Female (n = 36) | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 19.34 ± 5.07 | 22.02 ± 6.13 | 17.47 ± 3.11 | .002 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.70 ± 3.84 | 26.31 ± 4.56 | 23.57 ± 2.80 | .011 |

| Basophils, % | 0.47 ± 0.26 | 0.52 ± 0.31 | 0.44 ± 0.2 | .259 |

| Eosinophils, % | 2.03 ± 1.87 | 1.83 ± 1.48 | 2.18 ± 2.13 | .490 |

| White blood cells, 103 cells/μL | 6.96 ± 2.72 | 7.4 ± 3.58 | 6.64 ± 1.87 | .345 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 28.64 ± 9.99 | 28.52 ± 9.54 | 28.72 ± 10.44 | .940 |

| Monocytes, % | 7.48 ± 3.36 | 6.8 ± 2.92 | 7.98 ± 3.6 | .185 |

| Neutrophils, % | 61.04 ± 12.74 | 61.97 ± 12.66 | 60.35 ± 12.95 | .634 |

| Platelets, 103 cells/μL | 228.85 ± 45.81 | 229.16 ± 48.86 | 228.62 ± 44.17 | .965 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.43 ± 1.32 | 13.6 ± 0.93 | 11.58 ± 0.81 | <.001 |

| Hematocrit, % | 37.16 ± 3.66 | 40.37 ± 2.78 | 34.87 ± 2.19 | <.001 |

| Red blood cells, M cells/μL | 4.31 ± 0.43 | 4.66 ± 0.34 | 4.05 ± 0.29 | <.001 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate,c mm/h | 8.44 ± 6.39 | 6.72 ± 5.65 | 9.64 ± 6.67 | .079 |

| Bovine gelatin immunoglobulin G,c U/mL | 366.75 ± 494.06 | 425.20 ± 598.60 | 326.15 ± 410.61 | .477 |

aValues are expressed as mean ± SD. Boldface indicates statistically significant difference between males and females.

bAn independent t test was used to compare the variables for male versus female patients.

cThese values were measured at baseline (preoperatively).

Unadjusted Associations Between Blood Cell Counts and Healing ACL Average Cross-sectional Area

Unadjusted associations between healing ACL average cross-sectional area and patient demographics and blood values are shown in Table 2. Higher ACL cross-sectional area was found to significantly correlate with older age (β = 0.63; P = .034; R 2 = 0.07) and male sex (β = 8.86; P = .003; R 2 = 0.14). None of the quantified blood values were significantly associated with average cross-sectional area of the healing ACL (P > .10 for all analyses). The blood cell type that had the lowest P value (but did not reach statistical significance) for the association with signal intensity was the percentage of monocytes (P = .096; R 2 = 0.05).

Table 2.

Unadjusted Association Between Operative Side ACL Average Cross-sectional Area and Measurements at Surgery (N = 61)a

| Measurement | β | 95% CI | P Value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.63 | 0.05 to 1.22 | .034 | 0.07 |

| Male sex | 8.86 | 14.61 to 3.10 | .003 | 0.14 |

| Body mass index | 0.51 | –0.28 to 1.29 | .199 | 0.03 |

| Basophils | 3.51 | –8.80 to 15.82 | .570 | 0.08 |

| Eosinophils | –0.77 | –2.44 to 0.89 | .359 | 0.02 |

| White blood cells | 0.06 | –1.03 to 1.14 | .919 | 0.00 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.07 | –0.25 to 0.38 | .676 | 0.00 |

| Monocytes | 0.78 | –0.14 to 1.69 | .096 | 0.05 |

| Neutrophils | –0.08 | –0.32 to 0.17 | .528 | 0.01 |

| Platelets | –0.04 | –0.11 to 0.02 | .202 | 0.03 |

| Hemoglobin | 1.44 | –0.89 to 3.77 | .223 | 0.03 |

| Hematocrit | 0.52 | –0.32 to 1.36 | .220 | 0.03 |

| Red blood cells | 5.72 | –1.52 to 12.96 | .119 | 0.04 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rateb | 0.12 | –0.36 to 0.61 | .606 | 0.01 |

| Bovine gelatin immunoglobulin Gb | 0.00 | –0.01 to 0.01 | .756 | 0.00 |

aBoldface indicates statistical significance. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

bThese values were measured at baseline (preoperatively).

Unadjusted Associations Between Blood Cell Counts and Healing ACL Normalized Signal Intensity

Unadjusted associations between healing ACL normalized signal intensity and patient demographics and blood values are shown in Table 3. No statistically significant association was found between age or sex and signal intensity (P > .15 for both associations). No statistically significant association was seen between any blood cell parameter and signal intensity. The blood cell type that had the lowest P value (but did not reach statistical significance) for the association with signal intensity was the percentage of eosinophils (P = .071; R 2 = 0.06).

Table 3.

Unadjusted Association Between Operative Side ACL Normalized Signal Intensity and Measurements at Surgery (N = 61)a

| Measurement | β | 95% CI | P Value | R 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | –0.01 | –0.02 to 0.03 | .152 | 0.03 |

| Female sex | 0.09 | –0.03 to 0.20 | .156 | 0.03 |

| Body mass index | 0.01 | –0.01 to 0.02 | .374 | 0.01 |

| Basophils | 0.05 | –0.19 to 0.29 | .694 | 0.00 |

| Eosinophils | 0.03 | 0.00 to 0.06 | .071 | 0.06 |

| White blood cells | –0.01 | –0.03 to 0.01 | .338 | 0.02 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.01 | .246 | 0.02 |

| Monocytes | 0.00 | –0.02 to 0.02 | .813 | 0.00 |

| Neutrophils | 0.00 | –0.01 to 0.00 | .218 | 0.03 |

| Platelets | 0.00 | –0.01 to 0.01 | .906 | 0.00 |

| Hemoglobin | –0.02 | –0.07 to 0.02 | .347 | 0.02 |

| Hematocrit | –0.01 | –0.02 to 0.01 | .401 | 0.01 |

| Red blood cells | –0.01 | –0.19 to 0.09 | .445 | 0.01 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rateb | 0.00 | –0.01 to 0.01 | .816 | 0.00 |

| Bovine gelatin immunoglobulin Gb | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | .829 | 0.00 |

aACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

bThese values were measured at baseline (preoperatively).

Adjusted Sex-Specific Models for the Association Between Blood Cell Counts and Healing ACL Average Cross-sectional Area

Adjusted models, including age and BMI, were studied to account for observed differences in the cross-sectional area parameters within sexes. After adjusting for previously significant independent variables from the univariate analyses (age) and performing the analysis in each sex, we noted associations of healing ACL average cross-sectional area with blood values at surgery for male and female patients, as shown in Table 4. For male patients, although no blood cell parameters met the criteria for a statistically significant association with cross-sectional area, the lowest P values for such an association were noted for hemoglobin (P = .055) and hematocrit (P = .051), with lower hemoglobin/hematocrit seen with a lower cross-sectional area. For female patients, a higher percentage of monocytes (β = 1.01; P = .049) was significantly associated with higher ACL average cross-sectional area.

Table 4.

Adjusted Association Between Operative Side ACL Average Cross-sectional Area and Blood Values at Surgery in Male and Female Patientsa

| Male | Female | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Value | Age Effect | Blood Cell Parameter Effect | Age Effect | Blood Cell Parameter Effect | ||||

| β | P Value | β | P Value | β | P Value | β | P Value | |

| Basophils | 0.28 | .517 | 3.26 | .700 | 0.58 | .334 | –1.56 | .862 |

| Eosinophils | 0.34 | .466 | 0.91 | .642 | 0.49 | .420 | –0.69 | .421 |

| White blood cells | 0.25 | .548 | –0.72 | .312 | 0.45 | .434 | 0.77 | .351 |

| Lymphocytes | 0.22 | .602 | 0.27 | .313 | 0.57 | .351 | –0.03 | .877 |

| Monocytes | 0.27 | .511 | 1.03 | .238 | 0.22 | .713 | 1.01 | .049 |

| Neutrophils | 0.25 | .540 | –0.22 | .287 | 0.60 | .318 | –0.04 | .792 |

| Platelets | 0.24 | .571 | –0.01 | .928 | 0.18 | .758 | –0.07 | .091 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.10 | .803 | –5.20 | .055 | 0.49 | .437 | –0.36 | .877 |

| Hematocrit | 0.169 | .663 | –1.72 | .051 | 0.45 | .474 | 0.08 | .924 |

| Red blood cells | 0.13 | .761 | –6.54 | .409 | 0.65 | .523 | 0.04 | .995 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rateb | 0.28 | .504 | 0.52 | .249 | 0.46 | .427 | 0.19 | .474 |

| Bovine gelatin immunoglobulin Gb | 0.23 | .590 | 0.00 | .671 | 0.45 | .445 | 0.00 | .862 |

aBoldface indicates statistical significance. ACL, anterior cruciate ligament.

bMeasured at baseline (preoperatively).

Correlation Between Postoperative Bovine Gelatin IgG and Healing ACL Average Cross-sectional Area and Normalized Signal Intensity

Linear regression was used to compare outcomes by bovine gelatin IgG level at 6 months postoperatively in quartiles. We noted no statistically significant effect of postoperative bovine gelatin IgG level on either MR outcome (P > .6 for both parameters).

Discussion

In both the adjusted and unadjusted models, physiologic platelet concentration had no effect on ligament cross-sectional area or normalized signal intensity of the ACL after a bridge-enhanced ACL repair. In the unadjusted model, both older age and male sex were associated with a larger cross-sectional area of healing ACL, yet neither had a significant effect on signal intensity of the tissue at 6 months. In a sex-specific analysis of cross-sectional area, after adjustment for the potentially confounding variables of age, BMI, and hemoglobin levels, a higher monocyte concentration was correlated with higher cross-sectional area of the healing ACL in female patients only. Although this association was statistically significant, further studies in larger numbers of patients will be required to determine whether this association is true in all populations. All other factors measured, including the physiologic concentration of platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, basophils, and bovine gelatin IgG, were not significantly associated with either MR parameter at 6 months postoperatively.

The factors found to significantly correlate with increased cross-sectional area of the healing ACL in the unadjusted analyses were male sex and older age. In this study, the women were significantly younger and had a lower BMI than the men (Table 2). Both younger age and female sex may indicate the patients with a smaller notch size at the time of surgery. Prior studies of bridge-enhanced ACL repair support femoral notch width as a predictor of healing ligament cross-sectional area.34,49 It is possible from the findings that male sex and age could be surrogate markers for notch size and could subsequently be indirect predictors of cross-sectional area of the healing ACL. Future studies will determine which of these factors are primary.

The finding in this clinical study that an increased physiologic concentration of platelets did not significantly affect the healing ligament cross-sectional area or signal intensity is less consistent with prior reports, where intentionally increased platelet concentration has been reported to help with wound healing15,16 and maturation of grafts after ACL reconstruction.5,24 The finding here is more consistent with findings in preclinical models, where intentionally increasing the platelet count did not improve the strength of an ACL repaired by use of a scaffold and PRP or improve the mechanical properties of an ACL graft.26,41 However, although the ranges of platelet counts in this cohort revealed that some patients had platelet counts twice as high as others, this study did not evaluate the effect of deliberately concentrating platelets in the blood added to the implant.

It is known that various blood values have sex-specific normalized values,42 and hence it is important to look at each sex independently, particularly for cross-sectional area where sex was found to have a significant effect. In female patients, a higher monocyte concentration was correlated with higher cross-sectional area of the healing ACL. Monocytes, like other types of WBCs, play a defensive role in the immune system, working to destroy intruders while also facilitating healing and repair. More specifically, monocytes are largely responsible for phagocytic degradation of microbes and particles as well as cytokine recruitment.18,52,54 One hypothesis as to why monocytes may have a positive effect on ACL cross-sectional area is their ability to differentiate into macrophages. In particular, the shift from “classic activation” macrophages to “alternative activation” macrophages in the wound site is a key step in inflammation resolution, with these cells working to phagocytose apoptotic neutrophils and hence promote tissue growth.8 The potential overall effect of monocytes on ACL healing in patients is not yet well understood, and whether there is an effect on all patients or only female patients also remains unclear. Further studies are needed to evaluate the effects of monocytes on ACL healing after ligament repair.

In addition to platelets, neutrophils, and basophils having no significant effect on either MR parameter, ESR and bovine gelatin IgG values at baseline were also not found to be significantly correlated with ACL cross-sectional area or signal intensity at 6 months. ESR has shown diagnostic accuracy in assessment of systemic inflammation, where an increased value is indicative of a greater volume of acute phase proteins in blood plasma.14,36 ESR was collected at baseline to determine whether higher levels of those proteins present preoperatively would affect the MR parameters of the healing ligament. Additionally, studies done using other forms of bovine collagen implants have noted that more than 10% and up to 100% of patients will develop bovine type 1 collagen antibodies33; however, IgG antibodies in this context are thought not to correlate with adverse events, hypersensitivity, or indeed implant rejection.43 It has also been demonstrated that peak levels occur at approximately 4 to 6 months postoperatively and that dietary exposure to bovine products likely accounts for a significant proportion of patients who have IgG antibodies detected.19,28 The findings in this study are consistent with these prior reports, where patient IgG antibodies to bovine type 1 collagen are not associated with adverse reactions, including low cross-sectional area or high signal intensity of the healing tissue.

There were several limitations to this study. Cross-sectional area and signal intensity were measured only at 6 months. Therefore, further studies are required to determine whether these findings would be upheld at longer time points. Also, in this cohort, male patients on average had larger intact ACL cross-sectional area compared with female patients. However, we did not find any associations between age and intact ACL cross-sectional area measured from the contralateral knee. It is possible that the observed associations are influenced by overall body size and knee characteristic (ie, notch width), which is the subject of ongoing studies. It has previously been demonstrated that volume (and, thus, cross-sectional area) and signal intensity of a healing ACL graft are associated with clinical and functional outcomes at 3 and 5 years after ACL reconstruction surgery.10 Moreover, although we attempted to look at commonly analyzed and manipulated blood values, it is possible that we inadvertently excluded other important risk factors. Subsequent blood manipulation studies in large animal models may be necessary to help explain the current findings and to continue identifying biological markers that may influence ACL healing outcomes. Moreover, although this is the largest clinical study of bridge-enhanced ACL repair to date, only 61 patients were enrolled in this study. Thus, the study may have been underpowered to detect other significant associations or to adjust for the effect of other contributing factors (ie, knee morphologic characteristics34,49). Finally, although we adjusted our associations to potential confounding factors, we did not correct for multiple testing because of the exploratory nature of this study. Future studies with larger numbers of participants are planned.

Conclusion

Although older age and male sex were associated with higher healing ligament cross-sectional area, the results of this study suggest that physiologic platelet count and prior exposure to bovine collagen were not significant predictors of healing ligament cross-sectional area or signal intensity at 6 months after BEAR.

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge the significant contributions of the clinical trial team including Bethany Trainor, Elizabeth Carew, and Shanika Coney. We would also like to acknowledge the contributions of our medical safety monitoring team of Joseph DeAngelis, Peter Nigrovic, and Carolyn Hettrich; our data monitors Maggie Malsch, Meghan Fitzgerald, and Erica Denhoff; and the clinical care team for the trial patients, including Kathryn Ackerman, Alyssa Aguiar, Judd Allen, Michael Beasley, Jennifer Beck, Dennis Borg, Jeff Brodeur, Stephanie Burgess, Melissa Christino, Sarah Collins, Gianmichel Corrado, Sara Carpenito, Corey Dawkins, Pierre D’Hemecourt, Jon Ferguson, Michele Flannery, Casey Gavin, Ellen Geminiani, Stacey Gigante, Annie Griffin, Emily Hanson, Elspeth Hart, Jackie Hastings, Pamela Horne-Goffigan, Christine Gonzalez, Meghan Keating, Ata Kiapour, Elizabeth Killkelley, Elizabeth Kramer, Pamela Lang, Hayley Lough, Chaimae Martin, Michael McClincy, William Meehan, Ariana Moccia, Jen Morse, Mariah Mullen, Stacey Murphy, Emily Niu, Michael O’Brien, Nikolas Paschos, Katrina Plavetsky, Bridget Quinn, Shannon Savage, Edward Schleyer, Benjamin Shore, Cynthia Stein, Andrea Stracciolini, Dai Sugimoto, Dylan Taylor, Ashleigh Thorogood, Kevin Wenner, Brianna Quintiliani, and Natasha Trentacosta. We thank the perioperative and operating room staff and the members of the Department of Anesthesia at Boston Children's Hospital who were extremely helpful in developing the perioperative and intraoperative protocols. We acknowledge the efforts of other scaffold manufacturing team members, including Gabe Perrone, Gordon Roberts, Doris Peterkin, and Jakob Sieker. We are grateful for the study design guidance provided by the Division of Orthopedic Devices at the Center for Devices and Radiological Health at the US Food and Drug Administration under the guidance of Laurence Coyne and Mark Melkerson, particularly the efforts of Casey Hanley, Peter Hudson, Jemin Dedania, Pooja Panigrahi, and Neil Barkin. We are especially grateful to the patients and their families who participated in this study. Their willingness to participate in research that may help others in the future inspires all of us.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted February 7, 2020; accepted February 21, 2020.

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: Funding was received from the Translational Research Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, the Children’s Hospital Orthopaedic Surgery Foundation, the Children’s Hospital Sports Medicine Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (grants R01-AR065462 and R01-AR056834). This research was also conducted with support from the Football Players Health Study at Harvard University. The Football Players Health Study is funded by a grant from the National Football League Players Association. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Medical School, Harvard University or its affiliated academic health care centers, the National Football League Players Association, Boston Children’s Hospital, or the National Institutes of Health. M.M.M. and Boston Children’s Hospital have equity interests in MIACH Orthopaedics, a company that has licensed the BEAR scaffolding technology from Boston Children’s Hospital. M.M.M. has also received honoraria from the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation and royalties from Springer Publishing. B.C.F. has received educational support from Smith & Nephew, consulting fees from the New York R&D Center for Translational Medicine and Therapeutics, and royalties from Springer and is a paid associate editor for The American Journal of Sports Medicine. D.E.K. has received educational support from Kairos Surgical. B.L.P. has equity interests in and is a consultant for MIACH Orthopedics. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Boston Children’s Hospital (protocol No. IRB-P00021470).

References

- 1. Alsousou J, Thompson M, Hulley P, Noble A, Willett K. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in trauma and orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(8):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amable PR, Carias RBV, Teixeira MVT, et al. Platelet-rich plasma preparation for regenerative medicine: optimization and quantification of cytokines and growth factors. Stell Cell Res Ther. 2013;4(3):67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson K, Seneviratne AM, Izawa K, et al. Augmentation of tendon healing in an intraarticular bone tunnel with use of a bone growth factor. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andia I. Platelet-rich plasma injections for tendinopathy and osteoarthritis. Platelets. 2012;4:8. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Andriolo L, Di Matteo B, Kon E, et al. PRP augmentation for ACL reconstruction. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:371746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anitua E, Zalduendo M, Troya M, Padilla S, Orive G. Leukocyte inclusion within a platelet rich plasma-derived fibrin scaffold stimulates a more pro-inflammatory environment and alters fibrin properties. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0121713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bagwell MS, Wilk KE, Colberg RE, Dugas JR. The use of serial platelet rich plasma injections with early rehabilitation to expedite grade III medial collateral ligament injury in a professional athlete: a case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2018;13(3):520–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ballock RT, Woo SLY, Lyon RM, Hollis JM, Akeson WH. Use of patellar tendon autograft for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the rabbit: a long-term histologic and biomechanical study. J Orthop Res. 1989;7(4):474–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Besta R, Shankar YU, Kumar A, Rajasekhar E, Prakash SB. MRI 3D CISS—a novel imaging modality in diagnosing trigeminal neuralgia: a review. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10(3):ZE01–ZE03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Biercevicz AM, Akelman MR, Fadale PD, et al. MRI volume and signal intensity of ACL graft predict clinical, functional, and patient-oriented outcome measures after ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biercevicz AM, Miranda DL, Machan JT, Murray MM, Fleming BC. In situ, noninvasive, T2*-weighted MRI-derived parameters predict ex vivo structural properties of an anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction or bioenhanced primary repair in a porcine model. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):560–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Biercevicz AM, Murray MM, Walsh EG, et al. T2* MR relaxometry and ligament volume are associated with the structural properties of the healing ACL. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(4):492–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Biercevicz AM, Proffen BL, Murray MM, Walsh EG, Fleming BC. T2* relaxometry and volume predict semi-quantitative histological scoring of an ACL bridge-enhanced primary repair in a porcine model. J Orthop Res. 2015;33(8):1180–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bray C, Bell LN, Liang H, et al. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein measurements and their relevance in clinical medicine. WMJ. 2016;115(6):317–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cieślik-Bielecka A, Glik J, Skowroński R, Bielecki T. Benefit of leukocyte- and platelet-rich plasma in operative wound closure in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:7649206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cieslik-Bielecka A, Skowroński R, Jędrusik-Pawłowska M, Pierchała M. The application of L-PRP in AIDS patients with crural chronic ulcers: a pilot study. Adv Med Sci. 2018;63(1):140–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, et al. Fate of the ACL-injured patient: a prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(5):632–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Das A, Sinha M, Datta S, et al. Monocyte and macrophage plasticity in tissue repair and regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(10):2596–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DeLustro F, Keefe J, Fong AT, Jolivette DM. The biochemistry, biology, and immunology of injectible collagens: Contigen™ Bard® collagen implant in treatment of urinary incontinence. Pediatr Surg Int. 1991;6(4-5):245–251. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dhurat R, Sukesh M. Principles and methods of preparation of platelet-rich plasma: a review and author’s perspective. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7(4):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Bielecki T, Jimbo R, et al. Do the fibrin architecture and leukocyte content influence the growth factor release of platelet concentrates? An evidence-based answer comparing a pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) gel and a leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2012;13(7):1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eirale C, Mauri E, Hamilton B. Use of platelet rich plasma in an isolated complete medial collateral ligament lesion in a professional football (soccer) player: a case report. Asian J Sports Med. 2013;4(2):158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Etulain J. Platelets in wound healing and regenerative medicine. Platelets. 2018;29(6):556–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Figueroa D, Figueroa F, Calvo R, et al. Platelet-rich plasma use in anterior cruciate ligament surgery: systematic review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(5):981–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fitzpatrick J, Bulsara M, Zheng MH. The effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of tendinopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(1):226–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fleming BC, Proffen BL, Vavken P, et al. Increased platelet concentration does not improve functional graft healing in bio-enhanced ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23(4):1161–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fleming BC, Vajapeyam S, Connolly SA, Magarian EM, Murray MM. The use of magnetic resonance imaging to predict ACL graft structural properties. J Biomech. 2011;44(16):2843–2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frank DH, Vakassian L, Fisher JC, Ozkan N. Human antibody response following multiple injections of bovine collagen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(6):1080–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gagliardi AG, Carry PM, Parikh HB, et al. ACL repair with suture ligament augmentation is associated with a high failure rate among adolescent patients. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(3):560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg MA. A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament–injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(11):2509–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hefti F, Muller W, Jakob RP, Staubli HU. Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993;1(3-4):226–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaplan N, Wickiewicz TL, Warren RF. Primary surgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament ruptures: a long-term follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18(4):354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Keefe J, Wauk L, Chu S, DeLustro F. Clinical use of injectable bovine collagen: a decade of experience. Clin Mater. 1992;9(3-4):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kiapour AM, Ecklund K, Murray MM, et al. Changes in cross-sectional area and signal intensity of healing anterior cruciate ligaments and grafts in the first 2 years after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(8):1831–1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lai MWW, Sit RWS. Healing of complete tear of the anterior talofibular cruciate ligament and early ankle stabilization after autologous platelet rich plasma: a case report literature review. Arch Bone Joint Surg. 2018;6(2):146–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lapic I, Padoan A, Bozzato D, Plebani M. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein in acute inflammation. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;153(1):14–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Z, Chen YA, Chow D, et al. Practical applications of CISS MRI in spine imaging. Eur J Radiol Open. 2019;6:231–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lidén M, Sernert N, Rostgård-Christensen L, Kartus C, Ejerhed L. Osteoarthritic changes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using bone–patellar tendon–bone or hamstring tendon autografts: a retrospective, 7-year radiographic and clinical follow-up study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(8):899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lind M, Menhert F, Pedersen AB. The first results from the Danish ACL reconstruction registry: epidemiologic and 2 year follow-up results from 5,818 knee ligament reconstructions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(2):117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Linko E, Harilainen A, Malmivaara A, Seitsalo S. Surgical versus conservative interventions for anterior cruciate ligament ruptures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mastrangelo AN, Vavken P, Fleming BC, Harrison SL, Murray MM. Reduced platelet concentration does not harm PRP effectiveness for ACL repair in a porcine in vivo model. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(7):1002–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mayo Clinic. Complete blood count (CBC) with differential, blood. Accessed January 30, 2019 https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/Clinical+and+Interpretive/9109

- 43. McClelland M, Delustro F. Evaluation of antibody class in response to bovine collagen treatment in patients with urinary incontinence. J Urol. 1996;155(6):2068–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meunier A, Odensten M, Good L. Long-term results after primary repair or non-surgical treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture: a randomized study with a 15-year follow-up. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17(3):230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murray MM, Fleming BC. Use of a bioactive scaffold to stimulate anterior cruciate ligament healing also minimizes posttraumatic osteoarthritis after surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(8):1762–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Murray MM, Fleming BC, Badger GJ, et al. Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair is not inferior to autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at 2 years: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(6):1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Murray MM, Flutie BM, Kalish LA, et al. The bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair (BEAR) procedure: an early feasibility cohort study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(11):2325967116672176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Murray MM, Kalish LA, Fleming BC, et al. Bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair: two-year results of a first-in-human study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(3):2325967118824356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Murray MM, Kiapour AM, Kalish LA, et al. Predictors of healing ligament size and magnetic resonance signal intensity at 6 months after bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(6):1361–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Murray MM, Martin S, Martin T, Spector M. Histological changes in the human anterior cruciate ligament after rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82(10):1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Odensten M, Lysholm J, Gillquist J. Suture of fresh ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament: a 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55(3):270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ogle ME, Segar CE, Sridhar S, Botchwey EA. Monocytes and macrophages in tissue repair: implications for immunoregenerative biomaterial design. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2016;241(10):1084–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oh JH, Kim W, Park KU, Roh YH. Comparison of the cellular composition and cytokine-release kinetics of various platelet-rich plasma preparations. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(12):3062–3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Olingy CE, San Emeterio CL, Ogle ME, et al. Non-classical monocytes are biased progenitors of wound healing macrophages during soft tissue injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Perrone GS, Proffen BL, Kiapour AM, et al. Bench-to-bedside: bridge-enhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair. J Orthop Res. 2017;35(12):2606–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Riboh JC, Saltzman BM, Yanke AB, Fortier L, Cole BJ. Effect of leukocyte concentration on the efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):792–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Selmi TAS, Fithian D, Neyret P. The evolution of osteoarthritis in 103 patients with ACL reconstruction at 17 years follow-up. Knee. 2006;13(5):353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vavken P, Fleming BC, Mastrangelo AN, Machan JT, Murray MM. Biomechanical outcomes after bioenhanced anterior cruciate ligament repair and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction are equal in a porcine model. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):672–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Webster KE, Feller JA. Return to level I sports after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: evaluation of age, sex, and readiness to return criteria. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(8):2325967118788045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weiler A, Peters G, Maurer J, Unterhauser FN, Sudkamp NP. Biomechanical properties and vascularity of an anterior cruciate ligament graft can be predicted by contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging: a two-year study in sheep. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(6):751–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, et al. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation, part I: continuous passive motion, early weight bearing, postoperative bracing, and home-based rehabilitation. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(3):217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wright RW, Preston E, Fleming BC, et al. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction rehabilitation, part II: open versus closed kinetic chain exercises, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, accelerated rehabilitation, and miscellaneous topics. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(3):225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Xu Z, Yin W, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative evaluation of leukocyte- and platelet-rich plasma and pure platelet-rich plasma for cartilage regeneration. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yoshida M, Marumo K. An autologous leukocyte-reduced platelet-rich plasma therapy for chronic injury of the medial collateral ligament in the knee. Clin J Sport Med. 2019;29(1):e4–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]