Abstract

In this study, the chloroplast genome sequencing of the Achyranthes longifolia, Achyranthes bidentata and Achyranthes aspera were performed by Next-generation sequencing technology. The results revealed that there were a length of 151,520 bp (A. longifolia), 151,284 bp (A. bidentata), 151,486 bp (A. aspera), respectively. These chloroplast genome have a highly conserved structure with a pair of inverted repeat (IR) regions (25,150 bp; 25,145 bp; 25,150 bp), a large single copy (LSC) regions (83,732 bp; 83,933 bp; 83,966 bp) and a small single copy (SSC) regions (17,252 bp; 17,263 bp; 17,254 bp) in A. bidentate, A. aspera and A. longifolia. There were 127 genes were annotated, which including 8 rRNA genes, 37 tRNA genes and 82 functional genes. The phylogenetic analysis strongly revealed that Achyranthes is monophyletic, and A. bidentata was the closest relationship with A. aspera and A. longifolia. A. bidentata and A. longifolia were clustered together, the three Achyranthes species had the same origin, then the gunes of Achyranthes is the closest relative to Alternanthera, and that forms a group with Alternanthera philoxeroides. The research laid a foundation and provided relevant basis for the identification of germplasm resources in the future.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Achyranthes L. is the herbaceous or subshrub plant, which distributed in the tropical and subtropical regions of both hemispheres, including 15 species. Among them, 3 species are found in China, that are Achyranthes bidentata, A. aspera and A. longifolia. Of which, A. bidentata is widely distributed in China, especially in Henan province1. The roots of A. bidentata is used as an important traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to treat bones fracture and osteoporosis1–3, and it is also used in the treatment of arthritis4 or enhance immunity5. Besides, it is a medicinal herb with the property of activating blood to regulate menstruation and it can be used to tonify the liver and kidney6. Even it is used as the medicine of anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory7, 8. The main active ingredients include polysaccharides9, saponins10, peptides, organic acids and other substances in A. bidentata. Because of these secondary metabolites, A. bidentata has a variety of physiological activities, which makes it have higher utilization value. The function of A. longifolia is similar to that of A. bidentate. A. aspera is a traditional herbal medicine, is widely distributed in India11, also distributed in Hunan of China. The roots was used as the medicine of anticancer12, antiarthritic13, anti-herpes virus14 and antifertility15.

Chloroplast is a characteristic organelle in green plant cells, and is the major site for photosynthesis of cells. The chloroplast has its own DNA and genetic system. The chloroplast plays an indispensable role in the evolution of plants16–18. As an important research object in the field of molecular evolution, phylogeny, and molecular markers, the chloroplast genome sequencing technology has been widely used in the phylogenetic research of various plant groups19.

With the acquisition of chloroplast genome sequence information of tobacco20, the structural characteristics of chloroplast genome were revealed, more and more plants have obtained corresponding chloroplast genome information21–24. However, there are fewer reports on medicinal plants25, 26. According to current research reports, the chloroplast genome of angiosperms generally has a highly conserved quadripartite structure with a length of 120–180 kb, including a small single-copy (SSC) region with a length of 16–27 kb, a large single-copy (LSC) region with a length of 80–90 kb, and a pair of inverted repeat regions (IRs)27–29.

At present, most of the researches on Achyranthes species are focused on its pharmacological activities and chemical components in worldwide, while the research were less common in the comparing and phylogenetic analysis chloroplast genome of Achyranthes species. By comparing the chloroplast genome sequences of plants, we can clearly observe the differences among the genomes of different species at the molecular level, and use them as the basis for species division and identification. The chloroplast genome of A.bidentata was reported in research of Park30 and Li31 Park et al. found that the chloroplast genome of Korean A.bidentata has the same structural characteristics of angiosperms, while there were the same results of Hubei A.bidentata in the research of Li31. With the emergence of chloroplast genome sequence, chloroplast genome is also expected to help solve the deeper system development branch. The phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast genome sequence was used to evaluate the evolutionary relationship among species now. In this study, the complete chloroplast genome sequences information of A. bidentate, A. longifolia and A. aspera were obtained by sequencing the whole chloroplast genome, and comparative analyses of their structure and function. All of these will provide valuable reference information for species evolution and phylogeny of Achyranthes, and provide new reference for the identification and development of plant resources in the future.

Results

Achyranthes Chloroplast (CP) Genome structure and content

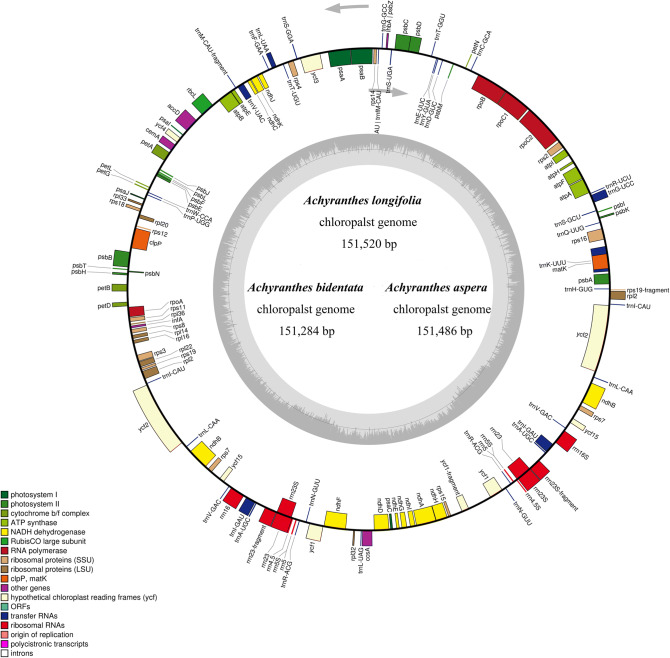

In this study, the whole chloroplast genome sequence of 3 Achyranthes species were obtained by sequencing and submitted to the NCBI database with the GenBank accession number MN953049 (A. longifolia), MN953050 (A. bidentata), MN953051 (A. aspera). Then these sequences were analyzed by various means. In this study, in order to validate the assembly sequences of Chloroplast genome of the three Achyranthes species, the junction sequences of LSC-IRb, IRb-SSC, SSC-IRa and IRa-LSC regions from three species were amplified and compared with assembly sequences. The results showed that the junction sequences of PCR amplification and assembly sequences were consistent up 99% or more. The results also indicated that the assembly sequences are accurate and reliable. The partial Blast results and DNA peak map of junction sequences was listed in Table S1. The results show that the chloroplast genome of them had a typical quadripartite structure (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Gene map of the Achyranthes chloroplast (CP) genome. Genes drawn inside the circle are transcribed clockwise, genes outside are transcribed counter clockwise. Different colors encode genes belonging to different functional groups. The area is darker gray and lighter gray in the inner circle corresponds GC content and AT content, respectively.

The results also indicated that the complete chloroplast genome had a length of 151,520 bp (A. longifolia), 151,284 bp (A. bidentata), 151,486 bp (A. aspera), respectively (Fig. 1).The structure of chloroplast genome included a small single-copy (SSC) region, a large single-copy (LSC) region and two inverted repeat (IR) regions. The length of the LSC region was 83,966 bp (A. longifolia), 83,732 bp (A. bidentata), 83,933 bp (A. aspera), respectively. Then, the length of the SSC region was 17,254 bp (A. longifolia), 17,252 bp (A. bidentata), 17,263 bp (A. aspera), respectively. Lastly, the IR region had a length distribution of 25,150 bp (A. longifolia), 25,150 bp (A. bidentata), 25,145 bp (A. aspera).

The GC content was 34.1–34.2% in LSC region. The GC content was 30% in SSC region, and the GC content was 42.5% in the IR regions. Thus, the GC content was the lowest in the SSC region. In addition, the total GC content was 36.4% (A. longifolia), 36.5% (A. bidentata), 36.5% (A. aspera), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of complete chloroplast genomes for three Achyranthes species.

| Species | A. longifolia | A. bidentata | A. aspera |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | |||

| Length (bp) | 83,966 | 83,732 | 83,933 |

| G+C (%) | 34.1 | 34.2 | 34.2 |

| Length (%) | 55.4 | 55.4 | 55.4 |

| SSC | |||

| Length (bp) | 17,254 | 17,252 | 17,263 |

| G+C (%) | 30.0 | 30.0 | 30.0 |

| Length (%) | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.4 |

| IR | |||

| Length (bp) | 25,150 | 25,150 | 25,145 |

| G+C (%) | 42.5 | 42.5 | 42.5 |

| Length (%) | 16.6 | 16.6 | 16.6 |

| Total | |||

| Length (bp) | 151,520 | 151,284 | 151,486 |

| G+C (%) | 36.4 | 36.5 | 36.5 |

The gene content and sequence of three Achyranthes species chloroplast genome are relatively conservative. Each of the three Achyranthes species chloroplast genome were predicted to encode 127 genes, including 82 protein-coding genes, 37 tRNA genes and 8 rRNA genes (Table 2). These genes classified to 17 groups according to their function. Additionally, the IRs regions contain 6 protein-coding and 7 tRNA genes, and the LSC and SSC region contain 67 and 11 protein-coding genes, respectively, meanwhile, the LSC and SSC region included 29 and one tRNA genes, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

List of genes annotated in the Achyranthes chloroplast genomes.

| Category | Group of genes | Name of genes |

|---|---|---|

| Self-replication | Large subunit of ribosomal proteins | rpl2*,a, 14, 16*, 20, 22, 23a, 33, 36 |

| Small subunit of ribosomal proteins | rps2, 3, 4, 7a, 8, 11, 12*,a, 14, 16*, 18, 19 | |

| DNA-dependent RNA polymerase | rpoA, B, C1*, C2 | |

| rRNA genes | rrn16Sa, rrn23Sa, rrn4.5Sa, rrn5Sa | |

| tRNA genes | trnA-UGC*,a, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnfM-CAU, trnG-UCC*, trnG-GCC, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU*,a, trnK-UUU*, trnL-CAA, trnL-UAA*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnN-GUU, trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-GAC, trnV-UAC*, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA | |

| Photosynthesis | Photosystem I | psaA, B, C, I, J |

| Photosystem II | psbA, B, C, D, E, F, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, T, Z, | |

| NADH oxidoreductase | ndhA*, B*,a, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, J, K | |

| Cytochrome b6/f complex | petA, B*, D*, G, L, N | |

| ATP synthase | atpA, B, E, F*, H, I | |

| Rubisco | rbcL | |

| Other genes | Maturase | matK |

| Protease | clpP* | |

| Envelope membrane protein | cemA | |

| Subunit acetyl-CoA-carboxylase | accD | |

| c-Type cytochrome synthesis gene | ccsA | |

| Conserved open reading frames | ycf1, 2a, 3*, 4, 15 |

*Genes containing introns.

aDuplicated gene (genes present in the IR regions).

Totally, there were 15 intron-containing genes, containing five tRNA genes and ten protein-coding genes (Table 3). Then thirteen genes included one intron, and the remaining two genes (ycf3 and clpP) included two introns of these 15 genes. The length of intron in trnK-UUU gene is largest, which was approximately 2,483 bp, and it is same to A. longifolia of Achyranthes, but there is a length of 2,480 bp in intron of trnK-UUU gene in A. aspera.

Table 3.

Length of exons and introns in genes with introns in the Achyranthes chloroplast genome.

| Species | Gene | Location | Exon I (bp) | Intron I (bp) | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon III (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. longifolia | trnK-UUU | LSC | 35 | 2,483 | 37 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 35 | 388 | 50 | |||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 37 | 594 | 38 | |||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 42 | 940 | 35 | |||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 820 | 35 | |||

| rps12a | LSC | 26 | 538 | 232 | 114 | ||

| rps16 | LSC | 214 | 900 | 41 | |||

| atpF | LSC | 410 | 795 | 145 | |||

| rpl16 | LSC | 402 | 986 | 9 | |||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 1602 | 763 | 432 | |||

| ndhB | IR | 756 | 676 | 777 | |||

| ycf3 | SSC | 153 | 756 | 228 | 785 | 126 | |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 768 | 642 | |||

| clpP | LSC | 228 | 623 | 292 | 842 | 71 | |

| petD | LSC | 8 | 783 | 475 | |||

| A. bidentata | trnK-UUU | LSC | 35 | 2,483 | 37 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 35 | 388 | 50 | |||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 37 | 593 | 38 | |||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 42 | 940 | 35 | |||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 820 | 35 | |||

| rps12a | LSC | 25 | 537 | 231 | 113 | ||

| rps16 | LSC | 214 | 900 | 41 | |||

| atpF | LSC | 410 | 743 | 145 | |||

| rpl16 | LSC | 402 | 966 | 9 | |||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 1602 | 763 | 432 | |||

| ndhB | IR | 756 | 676 | 777 | |||

| ycf3 | SSC | 153 | 756 | 228 | 785 | 126 | |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 768 | 642 | |||

| clpP | LSC | 228 | 623 | 292 | 841 | 71 | |

| petD | LSC | 8 | 783 | 475 | |||

| A. aspera | trnK-UUU | LSC | 35 | 2,480 | 37 | ||

| trnL-UAA | LSC | 35 | 388 | 50 | |||

| trnV-UAC | LSC | 37 | 594 | 38 | |||

| trnI-GAU | IR | 42 | 940 | 35 | |||

| trnA-UGC | IR | 38 | 820 | 35 | |||

| rps12a | LSC | 25 | 537 | 231 | 113 | ||

| rps16 | LSC | 214 | 900 | 41 | |||

| atpF | LSC | 410 | 790 | 145 | |||

| rpl16 | LSC | 402 | 985 | 9 | |||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 1602 | 762 | 432 | |||

| ndhB | IR | 756 | 676 | 777 | |||

| ycf3 | SSC | 153 | 756 | 228 | 784 | 126 | |

| petB | LSC | 6 | 776 | 642 | |||

| clpP | LSC | 228 | 622 | 292 | 844 | 71 | |

| petD | LSC | 8 | 784 | 475 |

aThe rps12 gene is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and the duplicated 3′ ends in the IR regions.

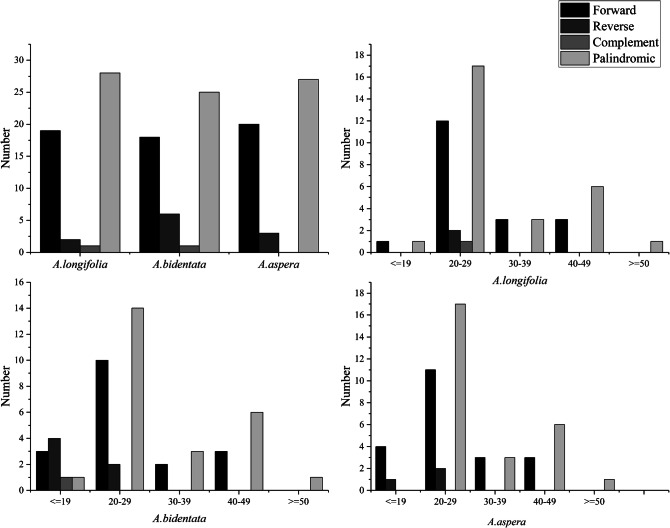

Long repeat structure analysis

In the 3 Achyranthes species chloroplast genome, there were 50 repeats were detected, which contained forward repeats, reverse repeats, complement repeats and palindromic repeats (Fig. 2). Then, there were 19 forward repeats, 2 reverse repeats, one complement repeats and 28 palindromic repeats in A. longifolia chloroplast genome. And there were 18 forward repeats, 6 reverse repeats, one complement repeats and 25 palindromic repeats in A. bidentata chloroplast genome. Then there were 20 forward repeats, 3 reverse repeats and 27 palindromic repeats in A. aspera chloroplast genome. However, there was no complement repeats in A. aspera chloroplast genome. These results also presented that it had a length about 20–29 bp in most forward repeats of three Achyranthes chloroplast genome. Then the length of most reverse repeats is below 19 bp, and the length of complement repeats is only below 19 bp, the length of most palindromic repeats was 20–29 bp in A. bidentata chloroplast genome. However, there was a different phenomenon in the A. longifolia and A. aspera chloroplast genome. In the A. longifolia chloroplast genome, the length of most reverse repeats and complement repeats were about 20–29 bp. Then the length of most reverse repeats was about 20–29 bp and there was no complement repeats in A. aspera chloroplast genome.

Figure 2.

Analysis of repeated sequences in three Achyranthes chloroplast genomes.

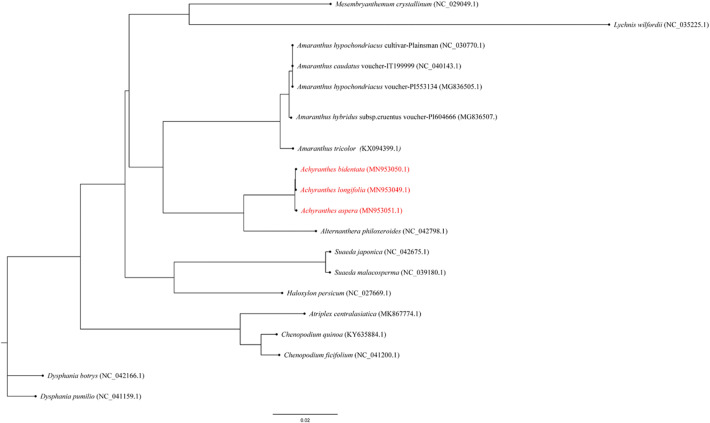

Simple sequence repeat (SSR) analysis

Simple sequence repeats (SSR), it was known as a microsatellite, including 1–6 nucleotides, and it was widely distributed the genome. In our study, the SSRs were analyzed in the Achyranthes chloroplast genome (Fig. 3), and the numbers and distributions of the SSRs were very similar in the three chloroplast genomes, but there were some differences. The result of research revealed that there were 88, 84, 83 SSRs in A. longifolia, A. bidentata, A. aspera chloroplast genome, and there were 82, 78, 76 mononucleotides SSRs in A. longifolia, A. bidentata, A. aspera, respectively. However, there is only one dinucleotide occurred in A. aspera. The result showed that the number of mononucleotides SSRs is maximum of A. longifolia among these Achyranthes species, and the dinucleotides repeat content is the least in all species. According to the result, the high variability of SSRs in these chloroplast genomes provides strong value and evidence for molecular breeding and identification of medicinal plants.

Figure 3.

Analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in three Achyranthes chloroplast genomes.

Comparative chloroplast genomic analysis in three Achyranthes species

In this study, the comparison of structure among three Achyranthes chloroplast genomes were performed. The result indicated that there was a length of 151,520 bp (A. longifolia), 151,284 bp (A. bidentata), 151,486 bp (A. aspera) in these Achyranthes chloroplast genome, and the length of IRs regions of A. bidentata is 25,150 bp, which has the same length with A. longifoli. And it had the smallest SSC region among these sequenced chloroplast genomes of Achyranthes.

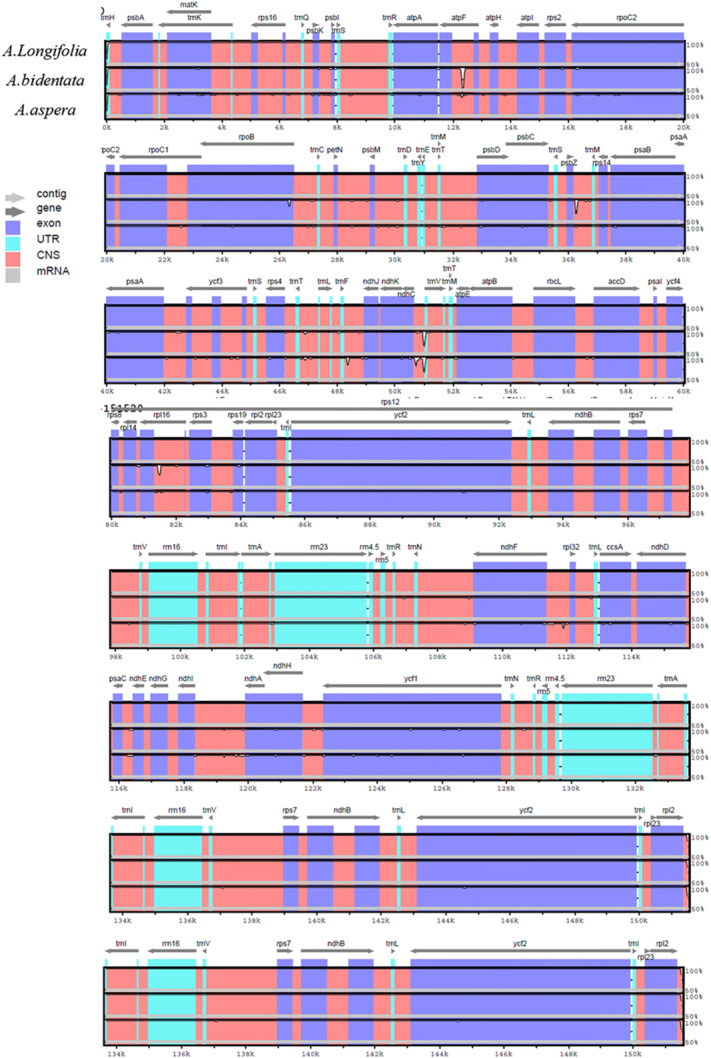

In addition, to analysis the DNA sequences divergence of related species, other chloroplast DNAs was premeditated using mVISTA, and with the chloroplast genome of A. bidentata as a reference (Fig. 4). The results showed that the LSC and SSC regions were no more difference than a pair of IRs regions in length. Besides, the coding regions were less flexible than the noncoding regions, and the highly divergent regions was found in the intergenic spaces amongst these Achyranthes chloroplast genomes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the chloroplast genomes using mVISTA. Gray arrows and thick black lines above the alignment indicate gene orientation. Purple bars represent exons, blue bars represent untranslated regions (UTRs), pink bars represent noncoding sequences (CNS), gray bars represent mRNA, and white peaks represent differences of genomics. The y-axis represents the percentage identity.

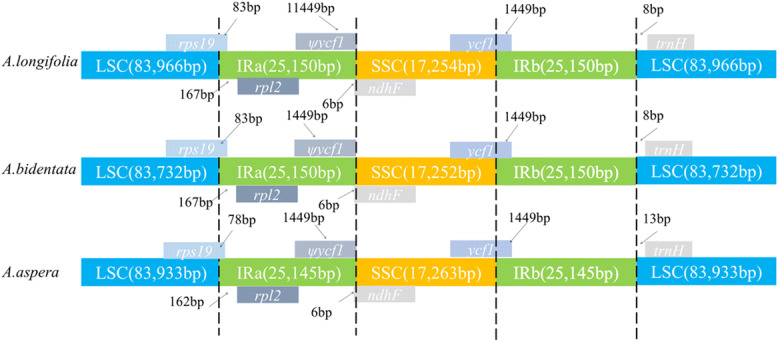

IR contraction and expansion in the chloroplast genome of Achyranthes

In our study, the detailed comparison of the IR-LSC and IR-SSC border structure among three species (A. longifolia, A. bidentata, A. aspera) was accomplished (Fig. 5). Findings revealed that the SSC/IRa connection was positioned in the ndhF region in three species of Achyranthes chloroplast genome, and extends a length of 6 bp into the IRa region in all three species. Meanwhile, the rps19 gene was positioned in the LSC/IRa junction and extend a length (A. longifolia, 83 bp; A. bidentata, 83 bp; A. aspera, 78 bp) into the IRa region. Then the SSC/IRb junction was located in the ycf1 region and extends a length (A. longifolia, 1449 bp; A. bidentata, 1449 bp; A. aspera, 1449 bp) into the IRb region in the chloroplast genome. In the intervening time, the trnH gene was generally present in the LSC region, and it had a length of 8 bp, 8 bp, 13 bp from the LSC/IRb border in the chloroplast genome of A. longifolia, A. bidentata, A. aspera, respectively.

Figure 5.

Comparison of border distance between adjacent genes and junctions of the LSC, SSC and two IR regions among the chloroplast genomes of three Achyranthes species. Boxes above or below the main line indicate the adjacent border genes. The figure is not to scale with respect to sequence length, and only shows relative changes at or near the IR/SC borders.

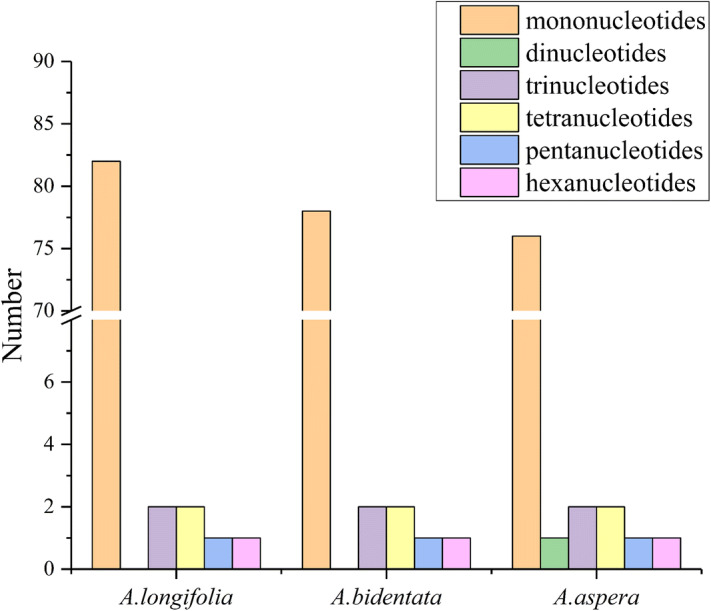

Phylogenetic analysis

Now there are more and more studies using complete chloroplast genome sequences to evaluate phylogenetic relationships between medicinal plants. Understanding the phylogenetic relationships between Achyranthes species and other Amaranthaceae could provide favorable guidance into the related angiosperm species. In this study, in order to analyze the phylogenetic relationships of Achyranthes species, the chloroplast genome sequences among 16 angiosperm species form NCBI (Fig. 6). On the basis of chloroplast genome date, the phylogenetic tree was built by the method of maximum likelihood (ML). The chloroplast genomes of 19 Centrospermae species were compared. The result showed that each genus and family of these species are divided into a taxonomic division, and constituted a monophyletic group in Centrospermae. The ML phylogenetic tree showed that there were divided into 13 clades among these analyzed species, and the result demonstrated Achyranthes is a monophyletic group, three species of Achyranthes belong to the one branch, which is separated from other genus of Amaranthaceae. In this taxon, A. bidentata had a strong sister relationship with A. longifolia. A. bidentata and A. longifolia were clustered together, the three Achyranthes species had the same origin, then the gunes of Achyranthes is the closest relative to Alternanthera, and that forms a group with Alternanthera philoxeroides. In addition, these results also provided effective evidence that the evolution of A. bidentata and A. longifolia occurred in the same direction.

Figure 6.

ML phylogenetic tree reconstruction including 19 species based on all chloroplast genomes.

Discussion

In this study, the chloroplast genome of three Achyranthes species was analyzed, the results showed that the three Achyranthes species in this study were content with the characteristics of angiosperms both in structure and content. The typical quadripartite structure of the Achyranthes chloroplast genome are consistent with the characteristics of the chloroplast genome in medicinal angiosperms32. The GC content was lower than the AT content in the chloroplast genome of three Achyranthes species, and all these proved that there was no significant difference in chloroplast genomes among three Achyranthes species. The phenomenon was universal in other angiosperms chloroplast genomes33–35. And the results also showed that the GC content the highest in the IR regions, which may be caused by the presence of large amounts of rRNA in the IR regions. The specific reasons will require further research. And the results of coding regions and the highly divergent regions amongst these Achyranthes chloroplast genomes, were also found in other plants chloroplast genomes36–39.

The length of exons and introns in genes were important information in plant chloroplast genome. In this study, the results showed that there were one gene (rps12) included three exons, and two genes (ycf3 and clpP) included two introns in three Achyranthes chloroplast genome. The rps12 gene is a trans-spliced gene with the 5′ end located in the LSC region and duplicated 3′ ends in the IRs regions40. Moreover, it has been reported that ycf3 is a gene closely related to photosynthesis41, 42. Consequently, the attainment of ycf3 gene will contribute to the further investigation of chloroplast in Achyranthes. The ycf1 gene also played a vital role in the chloroplast genome, there were the related reports on gene function of ycf1, these reports revealed ycf1 is an important pseudogene for the chloroplast genome variation and encoding of Tic214 in plants43, 44.

According to the previous reports, these introns played a vital role in the regulation of the gene expression45, which could adjust the level of the gene expression in a special spatiotemporal46, 47. Moreover, we found that some phenomenon in the chloroplast genomes, such as the intron or gene losses48–50, and the regulating function of intron have been found in many plants chloroplast genome51, 52. However, now there were no related research on the introns regulation mechanism of Achyranthes. Therefore, we could attain more useful information through the further studies of introns in the chloroplast genomes. The information of chloroplast genome could provide important theoretical basis for plant resource identification, especially medicinal plants.

Long repeats and the SSRs of the chloroplast genome were the vital information for identification of plant germplasm resources and molecular markers. Studies have shown that there are more than 30 bases of 14 repeats in S.miltiorrhiza chloroplast genome, similar, the repeats of ≥ 30 bases were 16, 15 and 16 in the chloroplast of A. longifolia, A. bidentate and A. aspera, respectively. The results of this study show that genes with long repeat sequences may be very suitable for genetic marker identification of related species, and the specific role needs to be proved by subsequent studies.

SSRs play a vital role in the chloroplast genomes. Due to its extreme variability, it was used to genetic research53–55. Previous report showed that the SSR was commonly distributed the genome, and the SSR was widely used to the genetic population structure and maternity analysis because of its unique uniparental in inheritance. Previous studies have shown that the mononucleotides were the most abundant repeats in A.formosae, and there was the same phenomenon in the three Achyranthes chloroplast genome. Therefore, the study of the chloroplast genome SSRs will greatly promote the investigation of species identification, genetic diversity and evolutionary process in Achyranthes56, 57.

Previous research had shown that IRs regions were the most conserved regions in the chloroplast genome19. Its contraction and expansion at the borders is a general evolutionary event, and which represent the dominant reason for the size variation and rearrangement of the chloroplast genome58–60. There were many reports that the chloroplast gene had a conservation order in most land plants, but there were also reports that many sequences were rearranged in the chloroplast genomes of most plant species, then the IR contraction and expansions with inversions, the inversions in the LSC region and the re-inversion in the SSC region were included61–63, and some reports showed that the extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes64. Because of the sequence rearrangements that modification of chloroplast genome structure in associated species may be related to the plant genetic diversity information, so it can be used for molecular identification and evolutionary research65.

With the continuous development of next generation sequencing technology, especially the application of second-generation sequencing technology, chloroplast genome sequencing has become simpler and easier than first generation sequencing. Moreover, at present, more and more researches have used the complete CP genome sequence to evaluate the phylogenetic relationship between angiosperms. In this study, The ML phylogenetic tree showed that there were divided into 13 clades among these analyzed species, and the results showed that there was a strong sister relationship between A. bidentate and A. longifolia. The chloroplast genomes were vital genomic resources for the reconstruction of precise high-resolution phylogenies66. As a member of the Amaranthaceae family, Achyranthes species contained vital genetic resources for the evolution and development of other species67, 68. The Achyranthes species and Alternanthera philoxeroides come from a monophyletic group, which is consistent with the results of Park30. However, the A.bidentate formed a group with Cyathula capitata and with 100% bootstrap in the research of Li31. Combined with our phylogenetic analysis and Li's research results, it is speculated that there may be a far-reaching relationship between A.bidentata of Hubei and A.bidentata from other regions, indicating that geographic isolation may have a greater impact on the interspecific relationship of Achyranthes. And in this study, we found that in the Amaranthaceae, each genus is basically clustered independently, indicating that there was a good monophyletic separation in this family.

At present, there are three species of Achyranthes species in China, and most of the studies are concentrated on A. bidentate and A. aspera in the world. Some studies have shown that the combined extract of Lycii Radicis Cortex and A. japonica had the effect of anti-osteoporosis69, in addition, it was also found that tannins isolated from leaf callus cultures of A.aspera and O.basilicum had the ability of anti-inflammatory and promoting wound healing70. Then some studies have also shown that the quality of chicken can be affected by adding the extract of A. japonica to chicken feed71. Therefore, it is speculated whether the addition of A. japonica extract to human diet will also affect the body muscle quality, which needs further research to prove. All these studies provided theoretical support for the research and development of Achyranthes in the future.

Now it has been shown that chloroplast genome can be used as super barcode to identify plant species72. According to our phylogenetic analysis of the chloroplast genome of three Achyranthes species, we speculated that the chloroplast genome of Achyranthes might be an important marker for species identification. Further research is needed to study this conjecture. The study results are of great value to the evaluation of genetic diversity and phylogenetic research of Achyranthes in the future. However, unfortunately, our study did not fully understand the relationship between genera. In addition, our phylogenetic study only is based on the chloroplast genome. If we want to fully understand the phylogeny of species in Amaranthaceae and even Centrospermae, we may need to analyze the nuclear genes of plants, and more genera should be included in the future. Nevertheless, our phylogeny research provided valuable resources for the classification, phylogeny and evolutionary history of Achyranthes.

Conclusions

Achyranthes L. is the extremely important medicinal plant. The chloroplast genome contains a large amount of available genetic information. At present, there is almost no research on the chloroplast genome of Achyranthes genus around the world. Consequently, it is extremely important to explore the genetic evolution and phylogeny by studying the genetic information of chloroplast genome of Achyranthes. In this study, the chloroplast genome sequencing of the three Achyranthes species was performed by next generation sequencing technology, the complete chloroplast genome sequence was obtained of the Achyranthes. This is an important finding about complete chloroplast genome of Achyranthes in China. The result revealed that the chloroplast genome of A. bidentata has a highly conserved structure, it was similar to angiosperms. Then we also determined the SSR, protein-coding gene sequence and repeated sequences, the phylogenetic analysis shows that there was a closer relationship between A. bidentata and A. longifolia. These results will offer the correlative supportable evidences and lay a solid foundation for the development of chloroplast genome of Amaranthaceae plants.

Materials and methods

Materials and DNA extraction

Fresh materials leaves of the A. bidentate were collected from Wuzhi County, Jiaozuo City, Henan Province of China (N35° 04′ 43.03″, E113° 24′ 7.69″), and A. aspera and A. longifolia were obtained from the field in Tongbai County, Nanyang City, Henan province in China (N32° 38′ 56.23″, E113° 43′ 50.46″). The fresh leaves of plant materials were quickly frozen with liquid nitrogen immediately after picking and cleaning, and kept in low temperature and dark. Total genomic DNA of them were extracted with Plant Genomic DNA Kit (TIANGEN, BEIJING) and the integrity of the extracted total genomic DNA was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, the total concentration of the extracted DNA was estimated by an ND-2000 spectrometer (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA)73, then the qualified samples were selected for subsequent experiments.

Chloroplast genome sequencing and assembly, annotation and structure

After the sample are qualified, the sequencing library was constructed by means of purified the fragment, repaired the terminal, added with A in 3′ segment, connected with sequencing connector, PCR amplification, etc. Primers used for assembly validation can be found as Supplementary Table S2 online. The library type is the DNA small fragment library of 250 bp, then sequencing was performed by an Illumina Hiseq X Ten platform pair-end sequencing method. Firstly, the low quality and redundant reads (Q < 20) were trimmed using Skewer-0.2.274, then the CP-like reads were extracted from those clean reads in comparison using the BLAST searches75 and these CP-like reads be used for sequence assembly with SOAPdenovo-2.0476, then to verifying the four junction regions between the IR regions and the LSC/SSC region, PCR amplification was performed. At last, resulting in a complete chloroplast genome sequence of A. bidentata. Gene annotation of the three Achyranthes species chloroplast genome were performed using the CpGAVAS with default parameters77, the physical chloroplast genome map was drawn using the OGDRAWv1.2 program with default parameters or subsequent manual editing78.

Long-repeats, simple sequence repeats and genome comparison

The REPuter was used to detect the forward (inverted) repeats. The simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in the chloroplast genome of A. bidentata were identified by using Phobos version 3.3.1279. The chloroplast genomic sequences alignment was carried out using the clustalw280. The mVISTA81 program in the Shuffle-LAGAN mode82 was used to compare the whole chloroplast genome of A. bidentata. with A. longifolia chloroplast genomes and A. aspera chloroplast genomes.

Phylogenetic analysis

In order to investigate the phylogenetic position of A.bidentata within Amaranthaceae lineages, then 16 complete chloroplast (CP) genome sequences were downloaded from the NCBI Organelle Genome database. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted using the whole cp genome sequences. The cp genome sequences alignment was carried out using the clustalw2. The best model was determined by modeltest-ng-0.1.6 software with default parameters83, ML analyse was performed using RAxML-NG v0.9.084 based on Linux edition using default parameters. The parameters were GTR {0.901389/1.745760/0.433440/0.576338/1.701638/1.000000} + FU {0.323117/0.177967/0.173322/0.325594} + G4m {0.329075}, noname = 1–244,745.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Shuai Guo from Institute of Chinese Materia Medical, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Beijing, China) for the data analysis. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1404829), Key project at central government level: the ability establishment of sustainable use for valuable Chinese medicine resources (2060302). This work also was supported Special fund for the construction of technical system of traditional Chinese medicine industry in Henan province.

Author contributions

J.X. and D.Y.H. conceived and designed the study. J.Y.X., and X.F.S. performed the experiments and wrote the paper. J.X. and B.S.L. analyzed the data. J.X. and D.Y.H. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The original sequencing datas have been submitted to the NCBI database and got the GenBank accession number MN953049 (A. longifolia), MN953050 (A. bidentata), MN953051 (A. aspera).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Jingya Xu and Xiaofeng Shen.

Contributor Information

Jiang Xu, Email: jxu@icmm.ac.cn.

Dianyun Hou, Email: dianyun518@163.com.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-67679-y.

References

- 1.Zhou S, Chen X, Gu X, Ding F. Achyranthes bidentata Blume extract protects cultured hippocampal neurons against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009;122:547–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He X, et al. The genus Achyranthes: a review on traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;203:260–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suh KS, Lee YS, Choi EM. The protective effects of Achyranthes bidentata root extract on the antimycin A induced damage of osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Cytotechnology. 2014;66(6):925–935. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9645-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu X-X, Zhang X-H, Diao Y, Huang Y-X. Achyranthes bidentate saponins protect rat articular chondrocytes against interleukin-1β-induced inflammation and apoptosis in vitro. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2016;33(2):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, et al. The protective effects of Achyranthes bidentata polypeptides on rat sciatic nerve crush injury causes modulation of neurotrophic factors. Neurochem. Res. 2013;38(3):538–546. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0946-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tao Y, Huang S, Yan J, Li W, Cai B. Integrated metallomic and metabolomic profiling of plasma and tissues provides deep insights into the protective effect of raw and salt-processed Achyranthes bidentata Blume extract in ovariectomia rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019;234:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He CC, Hui RR, Tezuka Y, Kadota S, Li JX. Osteoprotective effect of extract from Achyranthes bidentata in ovariectomized rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang QH, et al. Three new phytoecdysteroids containing a furan ring from the roots of Achyranthes bidentata Bl. Molecules. 2011;16:5989–5997. doi: 10.3390/molecules16075989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuying L, et al. Effects of Achyranthes bidentata polysaccharides on intestinal morphology, immune response, and gut microbiome in yellow broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coli K88. Polymers. 2018;10(11):1233. doi: 10.3390/polym10111233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitaine-Offer AC, et al. Bidentatoside I, a new triterpene saponin from Achyranthes bidentata. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:243–245. doi: 10.1021/np000464a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anand M, Ranjitha J, Alagar M, Selvaraj V. Phytoconstituents from the roots of Achyranthes aspera and their anticancer activity. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2017;53:189–191. doi: 10.1007/s10600-017-1946-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chakraborty A, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of Achyranthes aspera leaves on Epstein-Barr virus activation and two-stage mouse skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2002;177:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gokhale AB, Damre AS, Kulkami KR, Saraf MN. Preliminary evaluation of anti-inflammatory and anti-arthritic activity of S. lappa,A. speciosa and A. aspera. Phytomedicine. 2002;9:433–437. doi: 10.1078/09447110260571689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee H, et al. Anti-herpes virus activities of Achyranthes aspera: an Indian ethnomedicine, and its triterpene acid. Microbiol. Res. 2013;168:238–244. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasudeva N, Sharma SK. Post-coital antifertility activity of Achyranthes aspera Linn. root. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;107:179–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Z, et al. Sequencing and structural analysis of the complete chloroplast genome of the medicinal plant Lycium chinense Mill. Plants. 2019 doi: 10.3390/plants8040087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw J, Lickey EB, Schilling EE, Small RL. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose noncoding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the hare III. Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:275–288. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada M. Chloroplast movement. Plant Sci. 2013;210:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniell H, Lin CS, Yu M, Chang WJ. Chloroplast genomes: diversity, evolution, and applications in genetic engineering. Genome Biol. 2016;17:134. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinozaki K, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. EMBO J. 1986;5:2043–2049. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park I, et al. Sequencing and comparative analysis of the chloroplast genome of Angelica polymorpha and the development of a novel indel marker for species identification. Molecules. 2019 doi: 10.3390/molecules24061038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma Q, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major economic species, Ziziphus jujuba (Rhamnaceae) Curr Genet. 2017;63:117–129. doi: 10.1007/s00294-016-0612-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuo LH, et al. The first complete chloroplast genome sequences of Ulmus species by de novo sequencing: genome comparative and taxonomic position analysis. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawabe A, Nukii H, Furihata HY. Exploring the history of chloroplast capture in Arabis using whole chloroplast genome sequencing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018 doi: 10.3390/ijms19020602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of holoparasite Cistanche deserticola (Orobanchaceae) reveals gene loss and horizontal gene transfer from its host Haloxylon ammodendron (Chenopodiaceae) PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58747. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Taxus chinensis var. mairei (Taxaceae): loss of an inverted repeat region and comparative analysis with related species. Gene. 2014;540:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Muller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011;76:273–297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Puerta MV, Abbona CC. The chloroplast genome of Hyoscyamus niger and a phylogenetic study of the tribe Hyoscyameae (Solanaceae) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e98353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of poisonous and medicinal plant Datura stramonium: organizations and implications for genetic engineering. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e110656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park I, Yang S, Kim WJ, Moon BC. Complete chloroplast genome of Achyranthes bidentata Blume. Mitochondrial DNA B. 2019;4(2):3456–3457. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1674219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Z-H, Li X-H, Ling L-Z, Ai H-L, Zhang S-D. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of a traditional Chinese medicine: Achyranthes bidentata (Amaranthaceae) Mitochondrial DNA B. 2019;5:158–159. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1698362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He L, et al. Complete chloroplast genome of medicinal plant Lonicera japonica: genome rearrangement, intron gain and loss, and implications for phylogenetic studies. Molecules. 2017 doi: 10.3390/molecules22020249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badger JH, et al. the complete chloroplast genome sequence of date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) PLoS ONE. 2010 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asaf S, et al. Chloroplast genomes of Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera and Arabidopsis lyrata ssp. petraea: Structures and comparative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07891-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raubeson LA, et al. Comparative chloroplast genomics: analyses including new sequences from the angiosperms Nuphar advena and Ranunculus macranthus. BMC Genom. 2007;8:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ni L, Zhao Z, Xu H, Chen S, Dorje G. The complete chloroplast genome of Gentiana straminea (Gentianaceae), an endemic species to the Sino-Himalayan subregion. Gene. 2016;577:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, et al. The complete chloroplast genome of Cinnamomum camphora and its comparison with related Lauraceae species. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3820. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng H, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) and comparison with related species of Rosaceae. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3919. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong WQ, Yang JH. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Morus cathayana and Morus multicaulis, and comparative analysis within genus Morus L. PeerJ. 2017;5:e3037. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo S, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Paeonia ostii. Molecules. 2018 doi: 10.3390/molecules23020246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boudreau E, Takahashi Y, Lemieux C, Turmel M, Rochaix JD. The chloroplast ycf3 and ycf4 open reading frames of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are required for the accumulation of the photosystem I complex. EMBO J. 1997;16:6095–6104. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naver H, Boudreau E, Rochaix JD. Functional studies of Ycf3: its role in assembly of photosystem I and interactions with some of its subunits. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2731–2745. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Cambiaire JC, Otis C, Lemieux C, Turmel M. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the chlorophycean green alga Scenedesmus obliquus reveals a compact gene organization and a biased distribution of genes on the two DNA strands. BMC Evol. Biol. 2006;6:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakai M. The TIC complex uncovered: The alternative view on the molecular mechanism of protein translocation across the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts. Biochem. Biophys. Acta. 1847;957–967:2015. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu J, et al. Panax ginseng genome examination for ginsenoside biosynthesis. Gigascience. 2017;6:1–15. doi: 10.1093/gigascience/gix093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Hir H, Nott A, Moore MJ. How introns influence and enhance eukaryotic gene expression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Niu DK, Yang YF. Why eukaryotic cells use introns to enhance gene expression: splicing reduces transcription-associated mutagenesis by inhibiting topoisomerase I cutting activity. Biol. Direct. 2011;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graveley BR. Alternative splicing: increasing diversity in the proteomic world. Trends Genet. 2001;17:100–107. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueda M, et al. Loss of the rpl32 gene from the chloroplast genome and subsequent acquisition of a preexisting transit peptide within the nuclear gene in Populus. Gene. 2007;402:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guisinger MM, Chumley TW, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Implications of the plastid genome sequence of typha (typhaceae, poales) for understanding genome evolution in poaceae. J. Mol. Evol. 2010;70:149–166. doi: 10.1007/s00239-009-9317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Callis J, Fromm M, Walbot V. Introns increase gene expression in cultured maize cells. Genes Dev. 1987;1:1183–1200. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.10.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emami S, Arumainayagam D, Korf I, Rose AB. The effects of a stimulating intron on the expression of heterologous genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013;11:555–563. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ebert D, Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009;9:673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong W, Xu C, Cheng T, Lin K, Zhou S. Sequencing angiosperm plastid genomes made easy: a complete set of universal primers and a case study on the phylogeny of saxifragales. Genome Biol. Evol. 2013;5:989–997. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dong W, et al. Comparative analysis of the complete chloroplast genome sequences in psammophytic Haloxylon species (Amaranthaceae) PeerJ. 2016;4:e2699. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Provan J. Novel chloroplast microsatellites reveal cytoplasmic variation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Ecol. 2000;9:2183–2185. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2000.105316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flannery ML, et al. Plastid genome characterisation in Brassica and Brassicaceae using a new set of nine SSRs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;113:1221–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kode V, Mudd EA, Iamtham S, Day A. The tobacco plastid accD gene is essential and is required for leaf development. Plant J. 2005;44:237–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khakhlova O, Bock R. Elimination of deleterious mutations in plastid genomes by gene conversion. Plant J. 2006;46:85–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao X, et al. the first complete chloroplast genome sequences in Actinidiaceae: genome structure and comparative analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Doyle JJ, Davis JI, Soreng RJ, Garvin D, Anderson MJ. Chloroplast DNA inversions and the origin of the grass family (Poaceae) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7722–7726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer JD, Nugent JM, Herbon LA. Unusual structure of geranium chloroplast DNA: a triple-sized inverted repeat, extensive gene duplications, multiple inversions, and two repeat families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:769–773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cosner ME, Jansen RK, Palmer JD, Downie SR. The highly rearranged chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum (Campanulaceae): multiple inversions, inverted repeat expansion and contraction, transposition, insertions/deletions, and several repeat families. Curr. Genet. 1997;31:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s002940050225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Haberle RC, Fourcade HM, Boore JL, Jansen RK. Extensive rearrangements in the chloroplast genome of Trachelium caeruleum are associated with repeats and tRNA genes. J. Mol. Evol. 2008;66:350–361. doi: 10.1007/s00239-008-9086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chumley TW, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Pelargonium x hortorum: organization and evolution of the largest and most highly rearranged chloroplast genome of land plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2175–2190. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moore MJ, Bell CD, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19363–19368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708072104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schwartz LM, Gibson DJ, Young BG. Life history of Achyranthes japonica (Amaranthaceae): an invasive species in southern Illinois. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 2016;143:2. doi: 10.3159/TORREY-D-14-00014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Satish KV, Pasha SV, Krishna PH, Reddy CS. Achyranthes coynei Santapau (Amaranthaceae): an endemic and threatened species from Kachchh Desert, India. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2015;38:281–282. doi: 10.1007/s40009-014-0338-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park E, et al. Anti-osteoporotic effects of combined extract of Lycii Radicis Cortex and Achyranthes japonica in osteoblast and osteoclast cells and ovariectomized mice. Nutrients. 2019 doi: 10.3390/nu11112716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Madieha A, Ali MS. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and wound healing potential of tannins isolated from leaf callus cultures of Achyranthes aspera and Ocimum basilicum. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;3:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park JH, Kim IH. Effects of dietary Achyranthes japonica extract supplementation on the growth performance, total tract digestibility, cecal microflora, excreta noxious gas emission, and meat quality of broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2020;99:463–470. doi: 10.3382/ps/pez533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hernandez-Leon S, Gernandt DS, de la Rosa JAP, Jardon-Barbolla L. Phylogenetic relationships and species delimitation in pinus section trifoliae inferrred from plastid DNA. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Urreizti R, et al. COL1A1 haplotypes and hip fracture. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2012;27:950–953. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jiang H, Lei R, Ding SW, Zhu S. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinform. 2014;15:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deng P, et al. Global identification of MicroRNAs and their targets in barley under salinity stress. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0137990. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gogniashvili M, et al. Complete chloroplast DNA sequences of Zanduri wheat (Triticum spp.) Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015;62:1269–1277. doi: 10.1007/s10722-015-0230-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu C, et al. CpGAVAS, an integrated web server for the annotation, visualization, analysis, and GenBank submission of completely sequenced chloroplast genome sequences. BMC Genom. 2012;13:715. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lohse M, Drechsel O, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW): a tool for the easy generation of high-quality custom graphical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes. Curr. Genet. 2007;52:267–274. doi: 10.1007/s00294-007-0161-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kraemer L, et al. STAMP: extensions to the STADEN sequence analysis package for high throughput interactive microsatellite marker design. BMC Bioinform. 2009;10:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mayor C, et al. VISTA: visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:1046–1047. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:W273–279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Darriba D, et al. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020;37:291–294. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original sequencing datas have been submitted to the NCBI database and got the GenBank accession number MN953049 (A. longifolia), MN953050 (A. bidentata), MN953051 (A. aspera).