Abstract

Background

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has been associated with an increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) in women. HIV-positive pre-menopausal women lose the cardio-protective effect of estrogen and are at a higher risk for developing CAD. Our study intended to assess the cardiovascular risk in HIV-positive pre-menopausal women.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) datasets. The 10-year Framingham risk score for developing CAD was calculated for HIV-positive and HIV-negative women. The individual risk factors contributing to CAD were compared. The populations’ intent to reduce their risk and their doctor’s advice to reduce the risk were analyzed. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Out of the available sample of 82,091 people, 9,635 women (11.7%) met the inclusion criteria of the study. Among them, 25 women were HIV-seropositive (0.25%). Though there was no significant difference in blood pressure, hemoglobin A1c, C-reactive protein, high-density lipoprotein or total cholesterol (P > 0.05), the mean Framingham risk score in pre-menopausal HIV-positive women (mean (M) = 2.12, standard deviation (SD) = 2.73) was significantly higher than the HIV-negative women (M = 0.95, SD = 1.94) (P < 0.01). Neither did majority of the HIV-positive women intend to decrease their cardiovascular risk nor did their healthcare providers advise them to do so.

Conclusions

The risk of developing CAD in pre-menopausal women is higher from traditional risk factors itself. While HIV is now proven to be an independent risk factor for developing CAD in women, focus should be on reducing the risk from traditional methods.

Keywords: HIV, Women’s health, Heart disease, Primary prevention

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the leading cause of death in United States as per the 2011 National Center for Health Statistics’ annual report [1]. The traditional risk factors for CAD are male gender, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, tobacco use, early family history of CAD and lack of physical activity [2, 3].

Lately, medical conditions such as end-stage renal disease (ESRD), autoimmune and inflammatory diseases affecting connective tissues (lupus and rheumatoid arthritis), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection have also been reported as the risk factors of CAD [4-6]. HIV infection is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), stroke and atherosclerosis [6, 7]. The mechanism of CAD in HIV-infected people is a result of a complex interplay of traditional CAD risk factors mentioned above, effects of the antiretroviral agents, and inflammatory and immunologic changes. All these factors lead to endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis leading to CAD [8].

Irrespective of the risk factors, pre-menopausal women have a lower risk and incidence of hypertension and CAD compared to age-matched men [9]. This gender advantage for women gradually disappears after menopause, suggesting that hormones play a cardio-protective role in women [10]. However, HIV-positive pre-menopausal women tend to lose the cardio-protective effect of estrogen and have a higher risk for CAD compared with their HIV-negative counterparts (HIV-negative pre-menopausal women). The HIV-positive pre-menopausal women should be more vigilant in reducing their risk for developing CAD.

Objectives of the study

The primary objective of this study was to compare the 10-year cardiovascular risk in pre-menopausal HIV-positive women and pre-menopausal HIV-negative women using Framingham risk score (Table 1) [11].

Table 1. Framingham Coronary Artery Disease Risk Calculator [11].

| Variables | Response |

|---|---|

| Age | __ years |

| Gender | Male/female |

| Total cholesterol | __ mmol/L |

| HDL cholesterol | __ mmol/L |

| Smoker | Yes/no |

| Diabetes mellitus | Yes/no |

| Systolic blood pressure | __mm Hg |

| Is the person taking medicines for high blood pressure? | Yes/no |

HDL: high-density lipoprotein.

We also evaluated the effectiveness of risk factor modification methods in HIV-positive women, whether physicians/healthcare providers counseled the HIV-positive patients (frequency) and whether these patients followed those instructions (adherence).

Materials and Methods

Our study utilized the national level datasets from NHANES, “National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey” from the National Center for Health Statistics of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [12]. We used the datasets from 1999 to 2014. This survey combines interviews and physical examinations conducted in a mobile examination clinic (MEC) [13, 14]. Fasting blood draws were taken in the morning after an overnight fast of at least 9 h.

All the pre-menopausal females older than 18 years of age and younger than 55 years old were included in the study. Participants with a history of stroke, CAD and angina were excluded from the study as our focus was on primary prevention of CAD in HIV patients. The other exclusion criteria were male gender, females less than 18 years, females more than 55 years, post-menopausal women and missing data.

The complex datasets from NHANES were consolidated and analyzed using SPSS v.19. The sample was divided into two groups: HIV-positive women and HIV-negative women. Framingham risk score was calculated and compared between the two groups [11]. Individual risk factors contributing to CAD including blood pressure, hemoglobinA1c, smoking, cholesterol levels and family history of CAD were compared. Also the physicians’ advice to reduce the risk (counseling on diet, exercise and weight) and patient’s intent to engage in lifestyle modifications were analyzed. Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test was used to compute the P-value for categorical variables such as demographics and health practices. Independent samples t-test was used to compare the continuous variables (body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, glucose, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and total cholesterol levels, triglycerides and hemoglobin A1c) between the two groups. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered as a statistically significant level.

The study was exempt from Institution Review Board approval as it did not involve any human subjects in the study.

Results

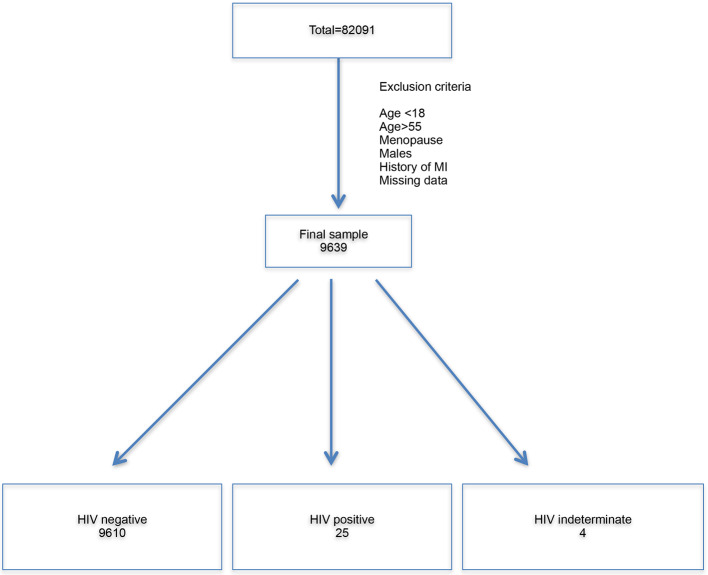

The NHANES datasets had a total sample of 82,091 people. From this sample, people less than 18 years and more than 55 years, males, post-menopausal women, people with history of CVDs were excluded. Sample with missing data was further excluded. The final sample available for analysis was 9,639. Out of them, 9,610 people were found to be HIV-negative, four were HIV-indeterminate and 25 were HIV-positive (Fig. 1). The basic demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating derivation of final sample. The total sample was 82,091. All the exclusion criteria were applied. The final sample was 9,639. Overall, 9,610 people were HIV-negative, four were HIV-indeterminate and 25 were HIV-positive. HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MI: myocardial infarction.

Table 2. Baseline Characteristics of the Sample.

| Characteristics | HIV-positive women (N = 25) | HIV-negative women (N = 9,610) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 39.44 (7.46) | 33.90 (8.94) | 0.147 |

| Race, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 1 (4.0) | 4,030 (41.9) | |

| African American | 21 (84.0) | 1,916 (19.9) | |

| Hispanic | 2 (8.0) | 2,844 (29.6) | |

| Others | 1 (4.0) | 820 (8.5) | |

| Married, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 4,802 (50) | 0.049 |

| Pregnant, n (%) | 1 (4.0) | 1,173 (12.2) | 0.358 |

| Family history of CAD, n (%) | 3 (12.0) | 1,199 (12.5) | 0.943 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 858 (8.9) | 0.242 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (4) | 537 (5.6) | 0.729 |

SD: standard deviation; CAD: coronary artery disease; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

The comparison of the component variables of Framingham risk score between the two groups is shown in Table 3. With no significant difference, the HIV-positive women were older than the women in the HIV-negative group (P = 0.147). The overall Framingham risk score of the two groups is also shown in Table 3. The component variables include systolic blood pressure, incidence of using medications for blood pressure, tobacco use, hemoglobin A1c, HDL cholesterol and total cholesterol. The table also shows the comparison of diastolic blood pressure and C-reactive protein. Overall, there seems to be no significant difference between any of these individual variables between the two groups. However, there is a significant difference between the two groups when it comes to the Framingham 10-year risk score. The mean Framingham risk score in pre-menopausal HIV-positive women (mean = 2.12, standard deviation (SD) = 2.73) was significantly higher than the pre-menopausal HIV-negative women (mean = 0.95, SD = 1.93) (P < 0.05).

Table 3. Comparison of Framingham Risk Score and Its Component Variables Between HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Pre-Menopausal Women.

| Variables | HIV-positive pre-menopausal women (N = 25) | HIV-negative pre-menopausal women (N = 9,610) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 39.44 (7.46) | 33.90 (8.94) | 0.147 |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 113.4 (23.1) | 109.3 (18.6) | 0.215 |

| Diastolic BP*, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 67.23 (17.3) | 66.0 (13.8) | 0.136 |

| On medicines for BP, n (%) | 5 (20.0) | 930 (9.7) | 0.082 |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 858 (8.9) | 0.242 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mean (SD) | 5.27 (0.42) | 5.33 (0.79) | 0.531 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 45.4 (9.8) | 57.4 (16.2) | 0.050 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 187.0 (42.5) | 192.5 (41.4) | 0.523 |

| C-reactive protein*, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.31) | 0.51 (0.82) | 0.113 |

| Framingham 10-year risk score | 2.12 (2.73) | 0.95 (1.93) | 0.010 |

*Diastolic blood pressure and C-reactive protein are not part of the Framingham risk score. SD: standard deviation; BP: blood pressure; HDL: high-density lipoprotein; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 4 shows the comparison of cardiovascular risk factor modification strategies between the two groups. The strategies we looked for included diet modification, smoking cessation, exercise and weight loss. The table illustrates the comparison of these strategies used by the patients and also the frequency of advices given by healthcare providers for their lifestyle modification. The results show that more there was no significant difference in terms of HIV-positive women trying to decrease their risk of developing a CAD by losing weight (P = 0.27), increasing exercise (P = 0.52) or modifying diet (P = 0.38).

Table 4. Comparison of Cardiovascular Risk Factor Modification Strategies Between HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Pre-Menopausal Women.

| HIV-positive pre-menopausal women (N = 25) | HIV-negative pre-menopausal women (N = 9,610) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician’s advices on lifestyle modification | |||

| Told to lose weight, n (%) | 4 (16.0) | 1,020 (10.6) | 0.383 |

| Told to exercise, n (%) | 7 (28.0) | 1,254 (13.0) | 0.027 |

| Told to modify diet, n (%) | 7 (28.0) | 1,277 (13.3) | 0.031 |

| Patient’s adherence to lifestyle modification | |||

| Trying to lose weight, n (%) | 7 (28.0) | 1,864 (19.0) | 0.277 |

| Trying to increase exercise, n (%) | 6 (24.0) | 1,821 (18.9) | 0.520 |

| Trying to modify diet, n (%) | 8 (32.0) | 2,356 (24.5) | 0.385 |

| Tried to quit smoking, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 163 (1.7) | 0.485 |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

When it comes to the physicians’ advice to reduce the patient’s risk of CAD, there was no difference in weight loss (P = 0.38) but there was a better pattern when it comes to increasing exercise (P = 0.02) and modifying diet (P = 0.03). About 28% of the women in HIV-positive group were advised to modify diet or increase exercise as compared to 13% in the HIV-negative group.

Discussion

This study shows that the Framingham risk of developing CAD in pre-menopausal HIV-positive women is higher compared to their non-HIV counterparts.

Treatment of HIV infection has become easily accessible and effective in many clinical settings across the globe. This has led to a significant decrease in the mortality and morbidity related to HIV- and AIDS-related complications of advanced HIV disease [15]. Though HIV-related mortality has been decreasing, there has been a steady increase in the proportion of deaths attributable to noninfectious complications of HIV including CVDs [16, 17]. It is a known fact that HIV-infected women have higher rates of developing CAD as compared to uninfected women. Studies have shown that the increased risk was persistent even after adjustment for demographic factors, other comorbidities and alcohol or cocaine abuse [18, 19]. As per the available data, women also represent 20% of all the new HIV infections [20]. African American women are disproportionately affected by the HIV infection epidemic, which is concurrent with the findings from our study (84% of HIV-infected women are African American).

Our results show that over a period of 16 years of the study, the risk of developing CVD is high from the traditional risk factors itself. Though there is no difference in terms of the risk posed by individual risk factors like tobacco use, high cholesterol, diabetes and hypertension but the cumulative effect is causing a significantly higher risk as seen by the difference in the Framingham risk between the two groups (Table 3). This shows that established risk factors themselves play a significant role in HIV-associated CAD than the disease itself.

However, according to the results from our study, there is no difference in the health behavior of the HIV-infected women (Table 4). The physicians and healthcare providers seem to be more sensitive in this regard and they did advice their HIV patients to focus on exercise and diet modification. However, it is not clear if this pattern is “by chance” or related to the fact that they are HIV-positive. There are studies to report that many cardiovascular interventions are underused in HIV populations, including aspirin therapy and lipid-lowering therapy [21, 22].

Since HIV seems to be an independent risk factor for developing CAD, it is prudent to sensitize both physicians and patients regarding the increased vulnerability to CAD in the HIV population. HIV-positive patients should be provided relevant information regarding smoking cessation, lifestyle modifications, periodic blood pressure and lipid-profile monitoring and diabetes screening. The evidence-based public health strategies that are currently in practice targeting traditional CAD risk factors for the general population should be further tailored to HIV-infected patients [23].

The biggest strength of our study is using national level data, a large number of variables and a large sample size. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first and the only study that has evaluated the cardiovascular risk patterns in women with HIV.

This study is not barring limitations. The study has a very small number of HIV-positive patients. This is a retrospective study based on self-reported data from CDC/NHANES survey. Studies have shown that self-reported data vary in reliability. The data collection was not done in a blinded pattern. More detailed information such as HIV viral load and compliance with HIV medications was not available which may affect the cardiovascular risk. Framingham risk score does not take into account high-sensitivity C-reactive protein higher levels that may be reflective of increased cardiovascular risk, particularly in women.

Conclusion

The intersection of HIV and CAD pathogenesis and patterns will pose a significant challenge from a clinical as well as a public health standpoint. Since Framingham and the other traditional CAD risk scores do not factor in HIV status, there is a need to develop methods to stratify CAD risk in the HIV population.

Acknowledgments

None to decalre.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

We do not have any direct or indirect affiliation with any organization with a financial interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Srikrishna V. Malayala designed the research study, collected the data, wrote the manuscript and performed the statistical analysis. Ambreen Raza collected the data and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(7):1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR. et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics - 2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack M, Gopal A. Epidemiology, Traditional and Novel Risk Factors in Coronary Artery Disease. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malayala SV, Raza A. Health behavior and perceptions among African American women with metabolic syndrome. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6(1):30559. doi: 10.3402/jchimp.v6.30559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sani MU. Myocardial disease in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: a review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120(3-4):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00508-008-0935-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F, Dezii CM, Kawabata H, Burtcel B, Maa JF. et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33(4):506–512. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solages A, Vita JA, Thornton DJ, Murray J, Heeren T, Craven DE, Horsburgh CR Jr. Endothelial function in HIV-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(9):1325–1332. doi: 10.1086/503261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Newby LK. et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women—2011 update: a guideline from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;123(11):1243–1262. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820faaf8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhupathy P, Haines CD, Leinwand LA. Influence of sex hormones and phytoestrogens on heart disease in men and women. Womens Health (Lond) 2010;6(1):77–95. doi: 10.2217/WHE.09.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. NHLBI. Risk assessment tool for estimating 10-year risk of having a heart attack: National Institute of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI]. May 2013. Available at: http://cvdrisk.nhlbi.nih.gov/calculator.asp. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey. October 2017. Available at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/Default.aspx. Accessed on June 8, 2020.

- 13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey mobile examination center tour [NHANES MEC]. October 2015. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx#plan-and-operations. Accessed on June 8, 2020.

- 14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National health and nutrition examination survey physician examination procedures manual. October 2015. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx#estimation-and-weighting-procedures. Accessed on June 8, 2020.

- 15.Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, Aschman DJ. et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–860. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonnet F, Chene G, Thiebaut R, Dupon M, Lawson-Ayayi S, Pellegrin JL, Dabis F. et al. Trends and determinants of severe morbidity in HIV-infected patients: the ANRS CO3 Aquitaine Cohort, 2000-2004. HIV Med. 2007;8(8):547–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2007.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti HIVdSG, Smith C, Sabin CA, Lundgren JD, Thiebaut R, Weber R, Law M. et al. Factors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. AIDS. 2010;24(10):1537–1548. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833a0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Womack JA, Chang CC, So-Armah KA, Alcorn C, Baker JV, Brown ST, Budoff M. et al. HIV infection and cardiovascular disease in women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3(5):e001035. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2506–2512. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. CDC. HIV surveillance - epidemiology of HIV infection. Division of HIVx002FAIDS Prevention, national Center for HIVx002FAIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexual Transmitted Diseases and Tuberculosis Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, Georgia: 2013. Accessed on July 28, 2019.

- 21.Malayala SV, Raza A. Compliance with USPSTF recommendations on aspirin for prevention of cardiovascular disease in men. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(11):898–906. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freiberg MS, Leaf DA, Goulet JL, Goetz MB, Oursler KK, Gibert CL, Rodriguez-Barradas MC. et al. The association between the receipt of lipid lowering therapy and HIV status among veterans who met NCEP/ATP III criteria for the receipt of lipid lowering medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):334–340. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0891-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The "Million Hearts" initiative - preventing heart attacks and strokes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(13):e27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.