Abstract

Objective:

Cranial neurosurgical procedures can cause changes in brain function. There are many potential explanations, but the effect of simply opening the skull has not been addressed, except for research into syndrome of the trephined. The “glymphatic circulation”, by which cerebrospinal fluid and interstitial fluid circulate through periarterial spaces, brain parenchyma, and perivenous spaces, depends on arterial pulsations to provide the driving force for bulk flow; opening the cranial cavity could dampen this force. We hypothesized that craniectomy, without any other pathological insult, is sufficient to alter brain function due to reduced arterial pulsatility and decreased glymphatic flow. Further, we postulated that glymphatic impairment would produce activation of astrocytes and microglia; with the re-establishment of a closed cranial compartment, the glymphatic impairment, astrocytic/microglial activation, and neurobehavioral decline caused by opening the cranial compartment might be reversed.

Methods:

Using 2-photon in vivo microscopy, the pulsatility index of cortical vessels was quantified through a thinned murine skull and then after craniectomy. Glymphatic influx was determined with ex vivo fluorescence microscopy of mice 0, 14, 28, and 56 days following craniectomy or cranioplasty; brain sections were immunohistochemically labeled for GFAP and CD68. Motor and cognitive performance was quantified with rotarod and novel object recognition tests at baseline and 14, 21, and 28 days following craniectomy or cranioplasty.

Results:

Penetrating arterial pulsatility decreased significantly and bilaterally following unilateral craniectomy, producing immediate and chronic impairment of glymphatic CSF influx in ipsilateral and contralateral brain parenchyma. Craniectomy-related glymphatic dysfunction was associated with an astrocytic and microglial inflammatory response, and with the development of motor and cognitive deficits. Recovery of glymphatic flow preceded reduced gliosis and return of normal neurologic function, and cranioplasty accelerated this recovery.

Conclusions:

Craniectomy causes glymphatic dysfunction, gliosis, and changes in neurologic function in our murine model of syndrome of the trephined.

Keywords: craniectomy, cranioplasty, syndrome of the trephined, glymphatic, CSF, arterial pulsatility

Introduction

Many patients undergoing cranial surgery develop changes in brain function that can last for weeks, months, or even be permanent. Causes include the underlying pathology addressed during surgery, manipulation of the brain tissue, ischemia caused by events during surgery, effects of anesthetics or other medications used in the perioperative period, and metabolic shifts caused by surgery18,26,28,40,41,44. Whether or not opening the cranium is sufficient to cause changes in brain function, however, has not been meaningfully addressed. Investigation of the effects of decompressive craniectomy is the lone exception6,20.

Trauma, stroke, infection, or neoplasia can cause increased intracranial pressure (ICP), and if ICP escapes medical control, decompressive craniectomy can prevent brain herniation or terminal decreases in cerebral perfusion pressure2,6,20,26. Syndrome of the trephined, changes in CSF hydrodynamics, and changes in cerebral perfusion have been observed after decompressive craniectomy, and cranioplasty can reverse these sequelae11,12,14,17,25,28,31. However, all these studies involve subjects with underlying brain disease that led to decompression in the first place; the specific effects of cranial opening on cerebral perfusion, CSF hydrodynamics, and neuronal or glial biology therefore remain unknown.

Our group recently defined a pathway facilitating the movement of CSF into the brain within periarterial spaces, and interstitial fluid (ISF) efflux from the parenchyma, at least in part, within perivenous spaces: the glymphatic system21,32,35. Cerebral penetrating arterial pulsations contribute the motile force necessary for generating bulk fluid flow within this pathway22. Impaired glymphatic CSF influx and ISF drainage cause accumulation of toxic metabolites such as amyloid-β and protein biomarkers of brain injury21,27,34,36, the development of gliosis23,27, and neurobehavioral deficits23. The glymphatic circulation is critically dependent on having a “closed” cranial compartment so arterial pulsations can generate the motile forces33,36,43.

We here hypothesized that craniectomy, in the absence of pathological insult, is sufficient to alter brain function by reducing arterial pulsatility and decreasing glymphatic flow. Further, we postulated that glymphatic impairment would trigger activation of astrocytes and microglia, and with the re-establishment of a closed cranial compartment, the neurobehavioral decline, glymphatic impairment, and astrocytic/microglial activation caused by opening the cranial compartment might be at least partially reversed.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All experiments used male mice between 8–12 weeks of age. FVB/N mice (Taconic Laboratories) were used for neurobehavioral assays, C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratories) were used for cerebrovascular pulsatility assessment, and C57BL/6 mice (Charles River Laboratories) were used for all other studies. For all experiments, animal use and justification are described within protocol number 2011–023, and approved by the University Committee on Animal Resources (UCAR) of the University of Rochester.

Anesthesia.

For all experiments utilizing anesthesia, a mixture of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) was dosed intraperitoneally.

Cerebrovascular pulsatility assessment.

In anesthetized mice, a midline scalp incision was made and the periosteum reflected. The skull was fixed with a custom 10-mm metallic frame. A 2-mm diameter thin-skull window centered over the right barrel field cortex was fashioned, as previously described22,39. Tetramethylrhodamine (TRITC)-conjugated dextran (2,000 kDa, 1% m/v in PBS, Molecular Probes) was injected in the tail vein. Following initial in vivo imaging of vascular pulsation, the thin-skull was converted to a craniectomy by carefully removing the 20-nm thinned region of skull and the dura with fine forceps. The mouse was returned to the microscope for repeat vessel pulsatility imaging. The cerebrovasculature was imaged through the thin-skull to a depth of 200 μm and through the craniectomy to a depth of 300 μm. A wavelength of 810 nm and a 590/43 nm BP emission filter were used for excitation and detection of intravascular TRITC-dextran, respectively. Vessels were identified as surface arteries and veins, penetrating arteries, or ascending veins, as previously described22. In each animal, 3 vessels of each type were arbitrarily selected for pulsation assessment, initially through the thin-skull, and then subsequently through the craniectomy. 3-second XT line scans (600 ns/line, 0.1 μm/pixel) were acquired orthogonal to the vessel axis to capture vessel diameter over the course of multiple cardiac and pulmonary cycles. Penetrating arteries and veins were acquired exactly 100 μm below the cortical surface to avoid differences in pulsation attributable to depth27. Using ImageJ (NIH, https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/), vessel diameters were calculated at each time point in the line scan. The absolute value of the area under the diameter-time plot integrated about a 500 ms running average of the vessel diameter was taken as vessel pulsatility, as previously described22. In total, 12 vessels of each type were assessed before and after craniectomy. In a separate set of experiments to address penetrating arterial pulsatility contralateral to craniectomy, thinned skull assessment of arterial pulsatility was performed on the left side before and after craniectomy on the right side, using the same techniques described above.

Craniectomy and cranioplasty surgical preparation.

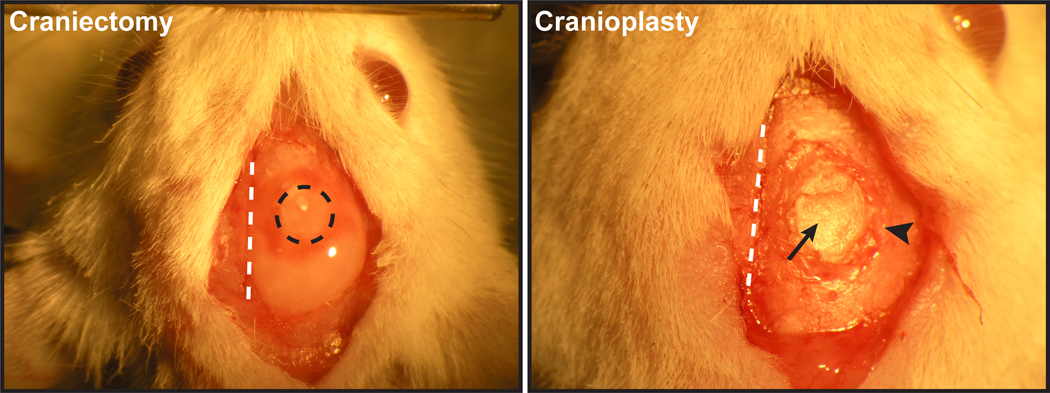

In anesthetized mice, a midline scalp incision was made and the periosteum reflected. Using a high-speed dental drill (Microtorque II, Ram Products), a 2-mm diameter craniectomy was created over the right temporoparietal cortex (−2.0 mm AP, 2.0 mm ML) with constant artificial CSF (aCSF) irrigation to prevent cortical heating by the drill bit. The bone flap was carefully lifted away and the underlying dura was removed with fine forceps under aCSF to prevent drying of the cortex (Fig. 1, left). The excised bone flap was inserted subcutaneously between the scapulae for preservation until the time of cranioplasty. The edges of the scalp were reapproximated with 4–0 prolene suture and the mouse returned to its home cage to recover. At 14 days following craniectomy, cranioplasty mice were re-anesthetized, and the previous scalp incision reopened and retracted laterally. The bone flap was retrieved from the pocket in the subcutaneous tissue between the scapulae and gently placed within the craniectomy defect. Cyanoacrylate and dental cement powder were applied circumferentially to adhere it to the surrounding skull (Fig. 1, right). The scalp was again closed with 4–0 prolene suture and the mouse returned to its home cage to recover.

Figure 1. Surgical preparation of craniectomy and cranioplasty.

(Left) A 2-mm diameter craniectomy window overlying the right temporoparietal cortex (−2.0 mm AP, 2.0 mm ML). Following drilling, the bone flap is carefully lifted from the skull and the underlying dura removed with fine forceps. In mice designated for cranioplasty, a small subcutaneous pocket is bluntly dissected between the scapulae for preservation of the bone flap until the time of cranioplasty. Sagittal suture (white dashed line); margin of craniectomy window (black dashed circle). (Right) At 14 days, the bone flap (black arrow) is retrieved from between the scapulae and gently placed within the craniectomy window. A mixture of cyanoacrylate and dental cement is used to secure the bone flap to the surrounding skull (black arrowhead). Sagittal suture (white dashed line).

CSF tracer injection.

There were three experimental groups in this study: craniectomy, cranioplasty, and non-operated age-matched controls. CSF tracer injections were performed as previously described21. In brief, a midline incision was made from inion to atlas, and skin and underlying muscle bellies retracted inferolaterally to directly visualize the cisterna magna. Tubing (PE 10, 0.28 mm I.D., Intramedic polyethylene tubing, Becton Dickinson) attached to a 100 μL syringe (Gastight #1710, 1.46 mm I.D., Hamilton) at one end and a 30G needle at the other was loaded with AlexaFluor555-conjugated ovalbumin (OA-555, 45 kDa, 0.5% m/v in aCSF, Molecular Probes). The needle was then advanced though the atlanto-occipital membrane at a 30º angle to avoid injury to any CNS structures. Cyanoacrylate and dental cement powder were applied from the occipital bone to the base of the wound to secure the needle within the cisterna magna. A syringe pump (11 Plus, Harvard Apparatus) injected 10 μL of OA-555 into the cisterna magna at a rate of 2 μL/minute. Following the 5-minute injection, OA-555 was allowed to circulate for an additional 25 minutes with the needle remaining in place to prevent tracer leak. After 30 minutes, the mouse underwent transcardial perfusion, first with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.4, Sigma), and then 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, pH 7.4, Sigma). Cerebral tissues were collected and post-fixed for 24 hours in 4% PFA, after which tissues were transferred to PBS.

Ex vivo fluorescence microscopy and measurement of glymphatic circulation.

Fixed cerebral tissues were sectioned on a vibratome (VT1000P, Leica) at 100 μm thickness. Every sixth coronal section, for a total of six sections representative of the cranio-caudal axis between +1.10 AP to −2.46 AP, were mounted (Superfrost Plus Microscope Slides, Fisher Scientific) with ProLong Gold Antifade with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Invitrogen) and cover slipped (22×40 mm, Fisherfinest Premium Cover Glass, Fisher Scientific). A stereomacroscope (MVX10, Olympus) with a 0.63x objective (MV PLAPO, 0.15NA) and a 2x zoom was used to perform epifluorescence microscopy. Image acquisition was controlled with MetaMorph Basic software (Molecular Devices). A wavelength of 525 nm and a 607/40 nm BP emission filter were used for excitation and detection of OA-555, respectively. Exposure times were kept constant across all experimental groups and time points. ImageJ was used for image quantification. Regions of interest (ROI) were drawn around the ipsilateral and contralateral total hemisphere, cortex, white matter (corpus callosum and external capsule), hippocampus, and subcortex. The percent area above a pre-determined threshold level (50 AU, 8-bit depth) was measured in each ROI.

Fluorescent immunohistochemistry and measurement of neuroinflammation.

Cerebral sections from the 14, 28 and 56 day craniectomy and cranioplasty, and control cohorts underwent immunohistochemical staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and Cluster of Differentiation 68 (CD68) to measure astrocytic and microglial reactivity, respectively23,27,38,46. Floating coronal sections were washed three times for 10 minutes each with PBS. Sections were blocked for 45 minutes at room temperature with 7% normal donkey serum (NDS, Millipore) in 0.5% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and PBS. The primary antibodies mouse anti-GFAP IgG (1:1000, Millipore, MAB360) and rat anti-CD68 IgG (1:250, Serotec, MCA1957) were applied to separate section sets with 1% NDS in a 0.1% Triton X-100 and PBS solution for 24 hours at 4ºC. Sections were washed as above, and the secondary antibodies Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 715–175-150) and Cy5-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG (H+L) (1:250, Jackson ImmunoResearch, 712–175-150) were applied for 2 hours at room temperature. All sections underwent a final wash, and were mounted. Immunofluorescence imaging was performed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (IX81, Olympus) with a 20x oil-immersion objective (UPlanApo, 0.8NA), in conjunction with Fluoview software (Version 4.3, Olympus). A laser tuned to 633 nm was used for excitation of Cy5, and PMT, gain and offset settings were kept constant for all sections. Within the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices of each section a 40 μm XYZ stack with a 5 μm step size was acquired. The imaged field was identified objectively by moving three fields of view (1024 × 1024 pixels) laterally from the midline and one field of view below the dorsal cortical surface (approximately +1.905 mm ML, −0.635 mm deep). ImageJ with the UCSD plugin package was used for image processing and analysis. Image stacks were compressed and converted to an 8-bit pixel depth. The percent area above a pre-determined threshold level (100 AU) was measured.

Assessment of neurobehavioral function.

Craniectomy, cranioplasty and control mice underwent neurobehavioral assessment at baseline and on days 14, 21 and 28. Locomotor function was evaluated with the open field test, as previously described23. Briefly, on assessment day mice were placed in a plastic chamber (53 cm long x 30 cm wide x 28 cm deep) and allowed to freely explore the chamber for 11 minutes. The outer surface of the chamber was wrapped with a non-translucent material to prevent the mouse from visually interacting with the surrounding environment. Video was recorded from above (Microsoft LifeCam Cinema) with the Multi Webcam Video Recorder Pro Software (DGTSoft). Any-maze Software (Version 4.99m) determined the mean speed and total distance traveled between minutes 2 and 11. Object memory was assessed using the novel object recognition test over a two-day period, as previously described3,23. Using the same chamber as described above (the acclimation phase), the mouse was removed and two unique objects were placed in the corners of the box furthest from the position of the experimenter. The mouse was then returned to the chamber for the learning trial, where it was allowed to freely explore the objects for 10 minutes. After 24 hours, one known object from the learning phase along with a novel object were placed in the rear corners of the box. For the test trial, the mouse was once more allowed to freely explore the objects for a 10-minute period. All trials were video recorded; only the first 5 minutes of the test trial were analyzed3. The time spent interacting with the known and novel objects was scored by hand, and the percent time spent interacting with the novel object was calculated: Novel Object Time / (Known Object Time + Novel Object Time) x 100. Coordinated motor function was evaluated using the rotarod test. Mice were placed on a rod rotating at a constant speed of 12 revolutions per minute for a maximum of 5 minutes. The latency to fall was determined when the mouse broke an optical beam below the rotating rod. The test was repeated a total of three times for every mouse on each assessment day, and the mean latency to fall was determined as the average of the three trials. The open field chamber, objects, and rotarod apparatus were all cleaned with 70% ethanol between each trial and every mouse.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software). All data was presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Differences were considered to be significant at a level of P<0.05. For the pulsatility analysis, the effect of craniectomy on each ipsilateral vessel type was evaluated by a repeated measures two-way ANOVA with a Sidak correction for multiple comparisons. For the pulsatility analysis of contralateral penetrating arteries, the effect of craniectomy was evaluated by a paired two-tailed t-test. For the glymphatic circulation analysis, comparisons were made between control, ipsilateral and contralateral craniectomy, and ipsilateral and contralateral cranioplasty, and evaluated by a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test within each ROI at all time points. For the neuroinflammation analysis, comparisons were made between control, ipsilateral and contralateral craniectomy, and ipsilateral and contralateral cranioplasty groups, and evaluated by a one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test at all time points. For the neurobehavioral assays, comparisons were made between control, craniectomy, and cranioplasty groups, and evaluated by a repeated measures two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test at all time points.

Results

Craniectomy leads to bilateral decreased cerebral penetrating arterial pulsatility

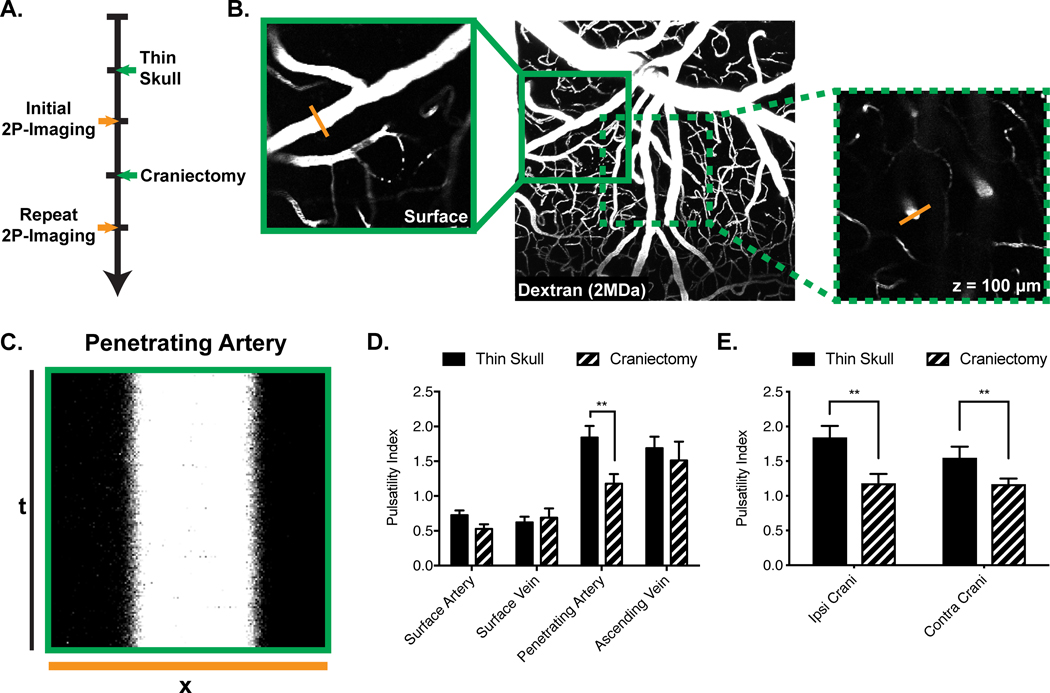

Arterial and venous pulsations were imaged with in vivo 2-photon microscopy. Following intravascular injection of a fluorescently labeled dextran (TRITC-dextran, 2,000 kDa), vascular imaging was first performed through a thinned-skull, and then subsequently the thin-skull was converted to an open craniectomy for repeat imaging of the same cortical vessels (Fig. 2A). Four levels of the cerebrovascular tree were assessed: pial or surface arteries and veins, penetrating arteries, and ascending veins, using previously validated techniques22. All penetrating arteries and ascending veins were evaluated at a depth of 100 μm below the cortical surface to avoid any differences in pulsatility which may arise due to cortical depth27 (Fig. 2B). XT (x-dimension, time) line scans orthogonal to the vessel axis were acquired to determine vessel diameter over a 3-second epoch (Fig. 2C). The pulsatility index was calculated as the summation of the absolute difference between the instantaneous diameter and the 500 ms running average of the diameter over the scanning period. We found a significant decrease in penetrating arterial pulsatility following craniectomy compared to when the skull was intact (thin skull vs craniectomy; 1.840±0.168 vs 1.178±0.137 (P=0.006)) (Fig. 2D). Further, there were no differences in the pulsatility index at any other levels of the cerebrovascular tree, suggesting that the influence of craniectomy on cerebrovascular pulsatility is specific to penetrating arteries. When we examined penetrating arterial pulsatility in the brain contralateral to craniectomy, we also found a significant decrease in penetrating arterial pulsatility following craniectomy compared to when the skull was intact (before vs after contralateral craniectomy; 1.546±0.163 vs 1.166±0.084 (P=0.002)).

Figure 2. Cerebral penetrating arterial pulsatility is reduced by craniectomy.

(A) Experimental timeline. (B) The cerebrovascular column is visualized by introducing a large fluorescently labeled dextran (TRITC-dextran, 2,000 kDa) intravenously (center image: collapsed 100 μm XYZ stack, 20x magnification). 3-second XT-line scans orthogonal to the vessel axis, capturing the dynamic change in vessel diameter across time, are acquired at the surface of the brain (orange line, left image) or at a depth of 100 μm below the brain’s surface (orange line, right image) to control for any changes in vascular pulsatility arising from variable cortical depth. (C) Representative XT line scan, where the horizontal axis corresponds to the orange lines seen in the left and right images of (B), and the vertical axis is the time vector. (D) Summary data demonstrating a decreased pulsatility index in the hemisphere ipsilateral to craniectomy compared to the thin skull preparation, specifically within penetrating arteries, but not at any other level of the cerebrovascular tree. **P<0.01, craniectomy vs thin-skull; two-way repeated measures ANOVA with a Sidak correction for multiple comparisons; n=4 mice, 12 vessels imaged in both conditions. (E) Summary data demonstrating decreased penetrating arterial pulsatility in both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. **P<0.01, craniectomy vs thin-skull; paired two-tailed t-test; n=4 mice, 12 vessels imaged for the ipsi crani groups and n=6 mice, 18 vessels imaged for the contra crani groups. All data is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Abbreviations: Ipsi=ipsilateral; Contra=contralateral; Crani=craniectomy.

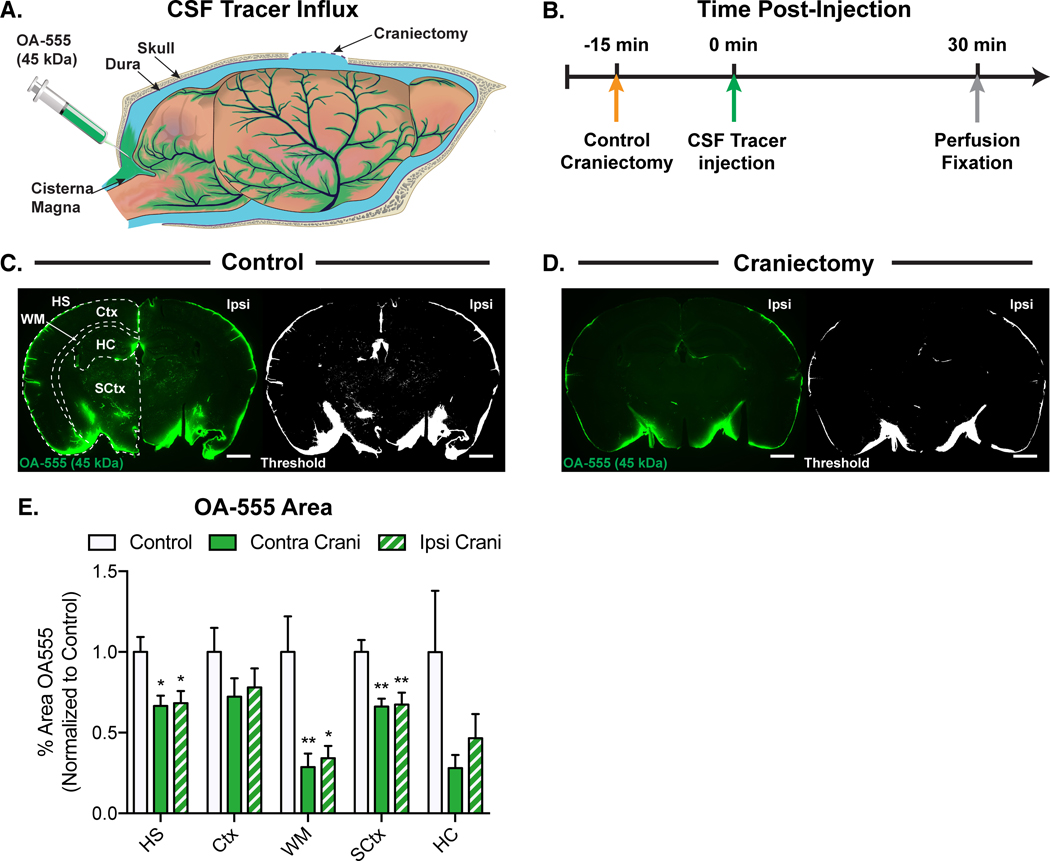

Craniectomy results in immediate impairment of glymphatic CSF influx into brain

Glymphatic circulation is critically dependent on penetrating arterial pulsations22, so we next sought to determine whether craniectomy impairs glymphatic influx of CSF into brain. The tracer molecule AlexaFluor555-conjugated ovalbumin (OA-555, 45 kDa) was injected into the cisterna magna (Fig. 3A) of mice immediately following craniectomy, as well as in a cohort of control mice. After allowing for 30 minutes of CSF circulation, cerebral tissues were fixed and prepared for ex vivo conventional fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3B). CSF penetrance into CNS structures was measured using the thresholded percent area occupied by OA-555 in the ipsilateral and contralateral total hemisphere, cortex, white matter (corpus callosum and external capsule), hippocampus, and subcortex in the control and craniectomy groups (Fig. 3C and D). The percent area occupied by OA-555 was significantly reduced in the ipsilateral and contralateral total hemisphere, white matter and subcortex after craniectomy (control vs ipsilateral and contralateral craniectomy; hemisphere: 1.000±0.093 vs 0.684±0.075 (P=0.030) and 0.665±0.064 (P=0.022); white matter: 1.000±0.220 vs 0.342±0.077 (P=0.014) and 0.287±0.084 (P=0.008); subcortex: 1.000±0.075 vs 0.674±0.073 (P=0.009) and 0.662±0.048 (P=0.007)) (Fig. 3E). Consequently, decreased penetrating arterial pulsatility following craniectomy is associated with an immediate and global impairment of glymphatic CSF influx into various cerebral tissues. Surprisingly, deeper cerebral structures (large white matter tracts and subcortical regions) demonstrated more severe glymphatic influx dysfunction than the cortex immediately underneath the craniectomy.

Figure 3. Decreased glymphatic influx immediately following craniectomy.

(A) Schematic diagram of injection of the fluorescent protein tracer, AlexaFluor555-conjugated ovalbumin (OA-555, 45 kDa), to the cisterna magna for the assay of glymphatic influx. (B) Experimental timeline. (C, left image) Five regions of interest drawn both ipsilateral and contralateral to the position of the craniectomy: hemisphere (HS), cortex (Ctx), white matter (WM; encompassing the corpus callosum and external capsule), hippocampus (HC) and subcortex (SCtx). (C) Representative image of control glymphatic CSF tracer influx (green), and the same image thresholded (white) to only capture pixels above a pre-determined intensity level. (D) Representative image of glymphatic tracer influx in craniectomy mice (green) and the same image after an intensity threshold has been applied (white). (E) Glymphatic CSF influx is measured by quantifying the % area of OA-555 above the applied intensity threshold in each of the regions of interest identified above. Summary data reveals that craniectomy results in significantly reduced glymphatic flow, both ipsilateral and contralateral to the craniectomy, at the level of the hemisphere, white matter, and subcortex. All data is normalized to control levels within each region of interest and is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test within each region of interest; n=6 mice/group. All scale bars=1 mm. Abbreviations: Ipsi=ipsilateral; Contra=contralateral; Crani=craniectomy.

Craniectomy results in prolonged failure of glymphatic CSF influx into brain

We next sought to determine if glymphatic impairment persists or recovers after craniectomy. We examined three experimental groups: age-matched non-operated controls, craniectomy, and cranioplasty cohorts. Mice in the craniectomy and cranioplasty groups had a section of skull and underlying dura removed from an area overlying the temporoparietal cortex (Fig. 1A). On day 14, cranioplasty mice had a second surgery for bone flap replacement (Fig. 1B). The fluorescent protein tracer, OA-555, was injected into the cisterna magna CSF on days 14, 28 and 56 of the experiment. After allowing for 30 minutes of CSF tracer circulation, animals underwent perfusion fixation and cerebral tissues were processed for ex vivo epifluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4A and B). CSF bulk flow into brain was measured as previously described (Fig. 4C). At 14 days following craniectomy, there was a significantly reduced percent area occupied by OA-555 in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres and cortices (control vs ipsilateral and contralateral craniectomy; hemisphere: 1.000±0.065 vs 0.592±0.111 (P=0.022) and 0.590±0.095 (P=0.021); cortex: 1.000±0.076 vs 0.507±0.084 (P=0.007) and 0.589±0.116 (P=0.023)), and a trend toward a lower area occupied in the contralateral subcortex (control vs contralateral subcortex; 1.000±0.057 vs 0.585±0.106 (P=0.065)) (Fig. 4D and G). At 28 days, there were no significant differences found in any of the ipsilateral or contralateral brain regions evaluated in either the craniectomy or cranioplasty cohorts (Fig. 4E and H), although there was a trend toward significantly increased OA-555 percent area in the white matter tracts ipsilateral to the craniectomy (control vs ipsilateral white matter; 1.000±0.221 vs 3.405±1.250 (P=0.064)) (Fig. 4E and H). At the 56-day time point, there were no significant differences in OA-555 percent area in any of the regions of interest in either the craniectomy or cranioplasty groups compared to controls (Fig. 4F and I), although there was a consistent trend across all anatomical areas for increased glymphatic influx in the mice that underwent cranioplasty at 14 days. We conclude that craniectomy is associated with reduced glymphatic CSF influx into brain up to 14 days following craniectomy. Glymphatic influx spontaneously recovers by 28 days independent of whether cranioplasty is performed, although cranioplasty is associated with a slight enhancement in glymphatic influx relative to control levels in white matter tracts after 28 days and in almost all brain regions of cranioplasty mice at 56 days.

Figure 4. Prolonged impairment of glymphatic influx due to chronic craniectomy.

(A) Schematic of cisterna magna injection of the fluorescent protein tracer, AlexaFluor555-conjugated ovalbumin (OA-555, 45 kDa), to assay glymphatic influx. (B) Experimental timeline. (C, top image) For image quantification, five regions of interest ipsilateral and contralateral to the site of the craniectomy or cranioplasty are drawn: hemisphere (HS), cortex (Ctx), white matter (WM; including corpus callosum and external capsule), hippocampus (HC), and subcortex (SCtx). (C–F, green images) Representative images of glymphatic CSF tracer influx in control, 14 day craniectomy, 28 day craniectomy (top image) and cranioplasty (bottom image), and 56 day craniectomy (top image) and cranioplasty (bottom image). (C and D, white images) Representative images demonstrating the application of a threshold to only include pixels above a pre-determined intensity from the above (green) images. (G–I) Glymphatic CSF tracer influx is measured by quantifying the thresholded % area of OA-555 in each of the regions of interest defined above. Summary data demonstrates persistent impairment of glymphatic flow, within both ipsilateral and contralateral structures, out to at least 14 days after craniectomy. By day 28, however, glymphatic CSF influx is found to spontaneously recover, independent of the presence of cranioplasty. All data is normalized to control levels within each region of interest and is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test within each region of interest; n=4–6 mice/group. All scale bars=1 mm. Abbreviations: Ipsi=ipsilateral; Contra=contralateral; Crani=craniectomy; CP=cranioplasty.

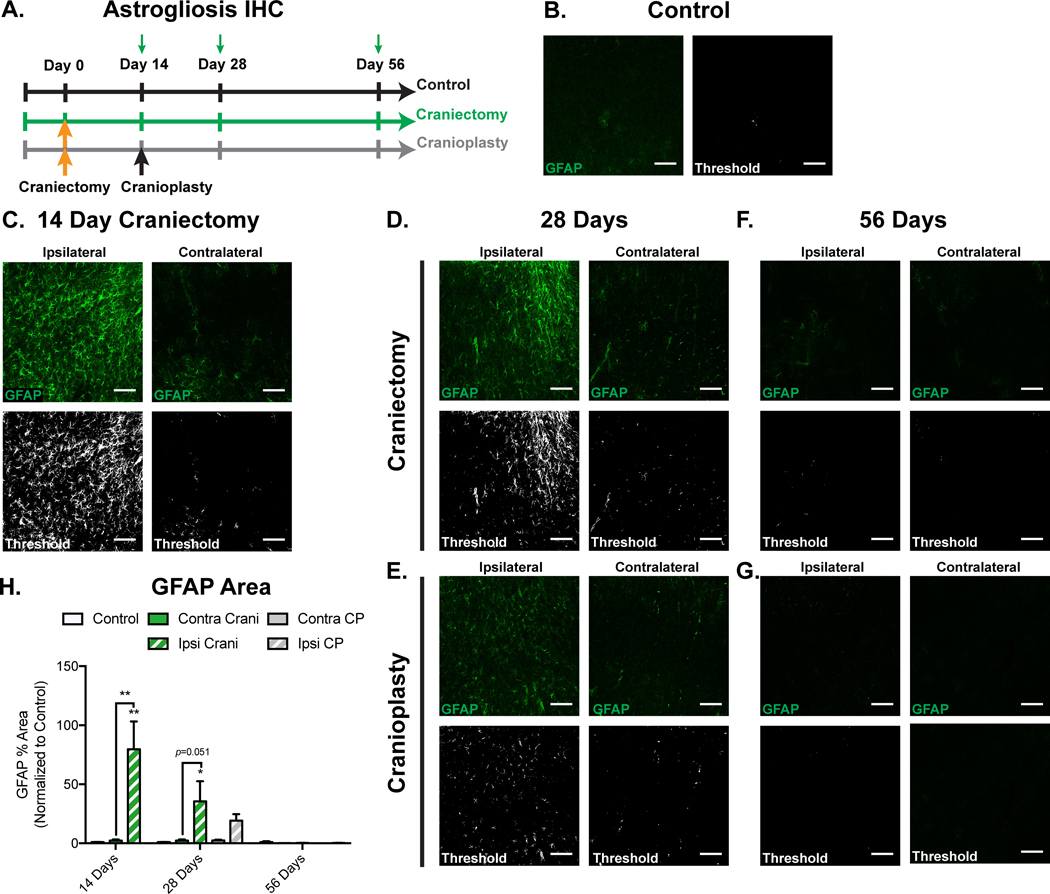

Craniectomy induces astroglial activation

We next asked whether impairment of glymphatic flow induces reactive astroglial activation. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on brain sections from the prior experiment investigating glymphatic influx after craniectomy or cranioplasty (see Fig. 4A and B). Briefly, following CSF tracer injection, mice were perfusion fixed on days 14, 28 and 56 of the experiment (Fig. 5A), and cerebral tissues underwent fluorescence immunohistochemistry for the astrocytic inflammatory marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)23,27,46. XYZ image stacks were acquired using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Thresholded percent area of GFAP immunofluorescence was used to quantify GFAP expression within ipsilateral and contralateral cortical high-powered fields. At 14 days, there was an 80-fold increase in the GFAP percent area in the ipsilateral cortex of craniectomy mice relative to controls (control vs ipsilateral cortex; 1.000± 0.180 vs 79.70± 23.48 (P=0.004)), and a 35-fold increase relative to the contralateral cortex (contralateral vs ipsilateral cortex; 2.268±1.014 vs 79.70±23.48 (P=0.004)) (Fig. 5B, C, and H). At 28 days there was an approximately 36-fold increase in the ipsilateral cortex of craniectomy mice relative to controls (control vs ipsilateral cortex; 1.000±0.180 vs 35.61±16.94 (P=0.029)), and while not statistically significant, a nearly 15-fold increase in the ipsilateral cortex relative to the contralateral cortex (contralateral vs ipsilateral cortex; 2.301±0.994 vs 35.61±16.94 (P=0.051)) (Fig. 5B, D, and H), suggesting that reactive astroglial activation persists at 28 days in mice with craniectomy. Cranioplasty at 14 days normalizes GFAP percent area in the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices relative to controls by 28 days (Fig. 5B, E, and H). By day 56 the GFAP intensity and percent area in the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices of craniectomy and cranioplasty mice had returned to control levels (Fig. 5B, F–H). We conclude that craniectomy is associated with persistent astroglial activation out to at least 28 days following craniectomy, but cranioplasty can accelerate return to a non-activated astrocyte phenotype.

Figure 5. Chronic craniectomy and glymphatic impairment drives reactive astrogliosis.

(A) Experimental timeline. (B–G) Representative images of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunofluorescence (green), and the same images with a threshold applied to capture pixels above a pre-determined intensity level (white), for controls (B), 14 day craniectomy (C), 28 day craniectomy (D) and cranioplasty (E), and 56 day craniectomy (F) and cranioplasty (G). All images are collapsed 40 μm XYZ stacks with a 5 μm step size. (H) Astrogliosis is measured by quantifying the % area above the defined intensity threshold occupied by GFAP within each high-powered field. Summary data demonstrates that there is persistent astrogliosis in the cortex ipsilateral to the craniectomy out to at least 28 days. Cranioplasty, however, accelerates recovery of the non-inflamed phenotype by day 28. All data is normalized to control levels within each region of interest and is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 versus control or between designated groups; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test at each time point; n=4–6 mice/group. All scale bars=100 μm. Abbreviations: Ipsi=ipsilateral; Contra=contralateral; Crani=craniectomy; CP=cranioplasty.

Craniectomy induces microglial activation

We hypothesized that impaired glymphatic flow could also be associated with microglial activation. Once again utilizing tissues from the previously discussed glymphatic influx experiment (see Fig. 4A and B), a similar experimental design was pursued as above. Briefly, following intracisternal delivery of CSF tracer on days 14, 28 and 56, cerebral tissues were fixed and subsequently underwent fluorescent immunohistochemical staining for Cluster of Differentiation 68 (CD68) (Fig. 6A). CD68 is highly expressed in monocytes and tissue macrophages, and its expression has been shown to preferentially label microglia and increase in microglia in states of CNS disease, injury and inflammation16,46. CD68 immunofluorescence was evaluated with XYZ image stacks acquired in ipsilateral and contralateral cortices with laser scanning confocal microscopy. In each high-powered field that was acquired, the percent area occupied by CD68 above a predetermined intensity threshold was measured. At 14 days, there was a significant 5-fold and 3-fold increase in the CD68 percent area in the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices of craniectomy mice, respectively, relative to control cortex (control vs ipsilateral and contralateral craniectomy; 1.000±0.289 vs 5.243±0.640 (P<0.0001) and 2.932±0.405 (P=0.032)). Further, percent area of CD68 was significantly greater ipsilateral to craniectomy than in the contralateral cortex (ipsilateral vs contralateral craniectomy; 5.243±0.640 vs 2.932±0.405 (P=0.011)) (Fig. 6B, C, and H). At 28 days the percent area of CD68 remained elevated in the ipsilateral cortex (control vs ipsilateral craniectomy; 1.000±0.289 vs 3.166±0.821 (P=0.042)), while expression in the contralateral cortex had normalized. Interestingly, mice in the cohort who underwent cranioplasty at 14 days demonstrated CD68 percent areas comparable to levels seen in controls by 28 days (Fig. 6B, D, E, and H). The percent area of CD68 had completely returned to baseline levels within the ipsilateral and contralateral cortices of both craniectomy and cranioplasty mice by 56 days (Fig. 6B, F–H).

Figure 6. Chronic craniectomy and glymphatic stagnation leads to reactive microgliosis.

(A) Experimental timeline. (B–G) Representative images of cluster of differentiation 68 (CD68) immunofluorescence (magenta), and the same images with a threshold applied to only capture pixels above a pre-determined intensity level (white), for controls (B), 14 day craniectomy (C), 28 day craniectomy (D) and cranioplasty (E), and 56 day craniectomy (F) and cranioplasty (G). All images depicted are collapsed 40 μm XYZ stacks with a 5 μm step size. (H) Microglial reactivity is measured by quantifying the % area above the defined intensity threshold occupied by CD68 within each high-powered field. Summary data shows that there is increased microglial activation ipsilateral and contralateral to the craniectomy at day 14. Further, this microgliosis persists out to at least 28 days in the cortex ipsilateral to the craniectomy; however, cranioplasty appears to normalize microglial CD68 expression by this same time point. All data is normalized to control levels within each region of interest and is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, ****P<0.0001 versus control or between designated groups; one-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparisons test at each time point; n=4–6 mice/group. All scale bars=100 μm. Abbreviations: Ipsi=ipsilateral; Contra=contralateral; Crani=craniectomy; CP=cranioplasty.

Craniectomy impairs object memory and coordinated movement

To link our observations about glymphatic failure and astroglial/microglial activation to changes in brain function, we sought to model the neurologic deficits found in syndrome of the trephined44, in particular motor and cognitive dysfunction. We established three experimental groups: age-matched non-operated controls, craniectomy, and cranioplasty cohorts. Mice in the craniectomy and cranioplasty groups had a section of skull and underlying dura removed from an area overlying the temporoparietal cortex on day 0. The open field and rotarod tests evaluated locomotor behavior and coordinated movement respectively. The novel object recognition test assessed object working memory. All three neurobehavioral assessments were performed prior to any surgical intervention, and at 14, 21, and 28 days of the experiment (Fig. 7A). Craniectomy and cranioplasty produced no change in the open field test at any of the time points (Fig. 7B and C) suggesting that our surgical procedures did not affect motor strength or activity level. At 14 days, mice with a craniectomy demonstrated a trend toward impaired performance on the rotarod (control vs craniectomy and cranioplasty; 24.398±2.047 vs 18.543±2.373 (P=0.203) and 17.447±3.355 (P=0.107)), and by 21 and 28 days, craniectomy mice were significantly impaired (21 and 28 days control vs craniectomy, respectively; 29.287±2.508 vs 15.700±2.112 (P=0.0003) and 29.740±1.715 vs 21.240±3.591 (P=0.037)). Interestingly, cranioplasty at 14 days resulted in an intermediate return of function on the rotarod at 21 days (control vs cranioplasty; 29.287±2.508 vs 23.247±4.501 (P=0.184) and equivalent function as controls at 28 days (control vs cranioplasty; 29.740±1.715 vs 27.943±2.459 (P=0.859)) (Fig. 7D). Fourteen days after craniectomy, mice showed a trend towards impaired function on the novel object recognition test compared to non-operated controls (control vs craniectomy and cranioplasty; 62.083±2.575 vs 52.783±1.508 (P=0.216) and 54.375± 3.239 (P=0.347)), and by 21 days, mice in both the craniectomy and cranioplasty cohorts showed significant impairment (control vs craniectomy and cranioplasty; 66.970±2.740 vs 53.809±3.405 (P=0.049) and 51.960±3.390 (P=0.020)) (Fig. 7E). Mice in the cranioplasty group regained function by 28 days (control vs cranioplasty; 61.272±3.798 vs 65.298±5.583 (P=0.747), while the craniectomy mice showed a trend towards a persistent failure (control vs craniectomy; 61.272±3.798 vs 50.831±4.110 (P=0.146)). Consequently, craniectomy in isolation leads to coordinated motor and object working memory deficits. Cranioplasty accelerates functional neurobehavioral improvement in both motor and cognitive domains in our mouse model.

Figure 7. Motor and cognitive deficits emerge following chronic craniectomy and prolonged glymphatic dysfunction.

(A) Experimental timeline: mice within the craniectomy, cranioplasty, and control cohorts undergo neurobehavioral assessment for locomotor function, coordinated motor function, and object working memory with the open field, rotarod, and novel object recognition tests, respectively, at baseline, and on days 14, 21 and 28. (B and C) Summary data finding no differences in the open field locomotor measures of mean speed (m/s) (B) and distance traveled (m) (C). (D) Summary data of coordinated motor performance on the rotarod demonstrating significantly shorter latencies to fall for the craniectomy cohort compared to controls at 21 and 28 days. Cranioplasty mice do not demonstrate significantly different fall latencies at any time points relative to controls. (E) Summary data of object working memory performance within the novel object recognition test finding significantly impaired novel object identification for both the craniectomy and cranioplasty cohorts at 21 days relative to controls. By 28 days, the cranioplasty group do not have any apparent deficits in identifying the novel object, however, there is a trend toward impaired novel object discernment for the craniectomy mice when compared to the cranioplasty cohort. All data is presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, magenta symbol indicates craniectomy vs control, blue symbol indicates cranioplasty vs control; repeated measures two-way ANOVA with a Tukey’s multiple comparison test at all time points; n=9–20 mice/group. Abbreviations: Crani=craniectomy; CP=cranioplasty.

Discussion

Craniectomy results in immediate and persistent impairment of glymphatic flow by reducing penetrating cerebral arterial pulsatility. This is associated with a robust astrocytic and microglial inflammatory response, and neurologic deficits in our animal model, similar to the clinical syndrome of the trephined. Although glymphatic function, reactive astrocytosis/microgliosis, and behavioral deficits can recover without cranioplasty in our model, cranioplasty accelerated the recovery of normal glial phenotype and behavior. This is the first study to suggest that suppression of flow through the glymphatic pathway, independent of CNS injury or disease, can drive neuroinflammation and functional neurologic deficits (Fig. 8). Our animal study may not directly relate to syndrome of the trephined because of the absence of ICP derangement, which is usually what leads to craniectomy in patients. However, our work highlights that removal of the skull leads to reduced arterial pulsatility, neuroinflammation, and a sharp suppression of glymphatic CSF influx. Combined these observations highlight that glymphatic CSF circulation is an important new consideration for neurosurgeons that may contribute long-term effects of the syndrome of the trephined. .

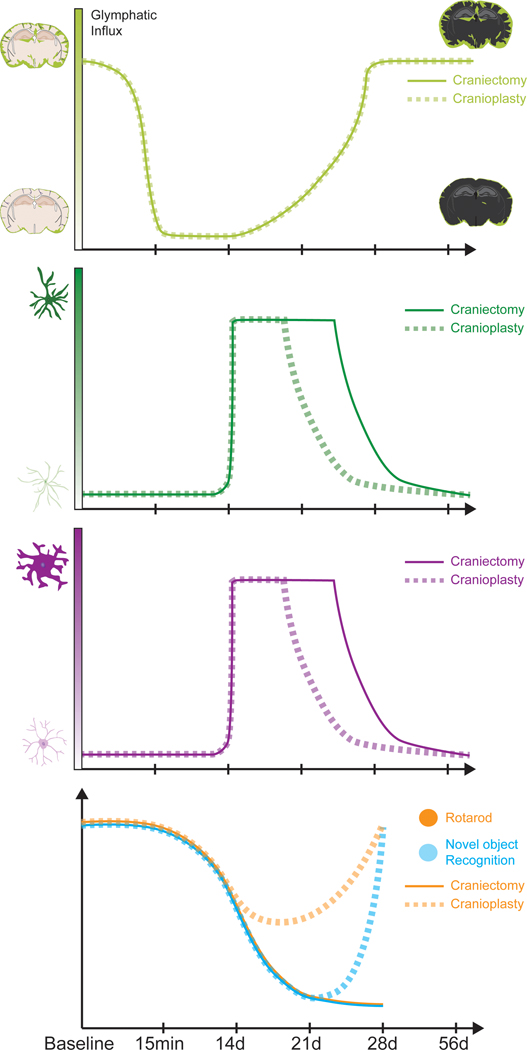

Figure 8. Summary of impact of craniectomy on glymphatic flow, neuroinflammation, and neurobehavioral function.

There is impaired glymphatic CSF influx immediately following decompressive craniectomy and lasting out to a point between 14- and 28-days following decompression, regardless of whether cranioplasty is performed. In association with this glymphatic stagnation, there is increased astrocytic and microglial reactivity at 14- and 28-days following craniectomy, however, if cranioplasty is performed there is a reduction in both GFAP and CD68 expression to control levels at 28-days. Finally, by 21 days following craniectomy, there is impaired cognitive and motor performance on the novel object and rotarod assessments, respectively, and motor deficits persist out to 28 days. If cranioplasty is performed, there is a trend toward impaired cognitive and motor function at 14 days, and there is significantly impaired cognition at 21 days, but all neurologic deficits are reversed by 28 days. Top panel: increasing light green color on y-axis represents increasing OA-555 % area. Middle panels: increasing dark green or purple color on y-axis represents increasing GFAP or CD68 % area, respectively. Bottom panel: y-axis represents latency to fall for the rotarod assessment and % time spent with the novel object for the novel object recognition test. Solid lines=craniectomy, dotted lines=cranioplasty.

Derangements of CSF hydrodynamics represent the most frequent complications in patients after decompressive craniectomy. Hydrocephalus occurs in nearly 15% of patients, subdural hygroma or effusion occurs in 27.4%28, and there are numerous observations that suggest subdural fluid collections typically appear before the onset of hydrocephalus11,17,18,44,47. Our observations suggest a mechanistic explanation: reduced glymphatic conductance of CSF into the brain parenchyma leads to upstream accumulation, first within the subarachnoid space (subdural hygroma), and if severe and persistent enough, later within the ventricular system (communicating hydrocephalus). Although the CSF production rates/g, CSF composition, and CSF clearance rates are similar from mice to humans1,7,8,10,42, the distance from the subarachnoid space to the deepest part of the brain, the simplified subarachnoid space of the lissencephalic mouse brain, and the upright posture of humans make it hard to compare macroscopic hydrodynamics between the two species.

Penetrating arterial pulsatility within the cerebral cortex generates a hydrostatic force that drives the movement of CSF into the brain parenchyma and the clearance of ISF and solute from the brain’s extracellular space22. Craniectomy results in reduced pulsatility of cortical penetrating arteries in our model, and in humans, decompressive craniectomy following head injury results in a significant bilateral reduction of the transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasonography measured pulsatility index, while cerebral blood flow increased (also measured by TCD)4,9,29. This suggests that the craniectomy performed in our study was not likely associated with decreased cerebral blood flow or any metabolic disturbances resulting from ischemia, although this was not specifically tested. The mechanism by which craniectomy leads to dampening of cerebrovascular pulsatility remains unknown. TCD pulsatility index may be an indirect measure of cerebrovascular resistance4,29. The pressure of tissue surrounding cerebral arteries may “push back” on penetrating vessels and influence the cross-sectional area of these vessels. When tissue pressure falls after opening the cranial compartment to atmospheric pressure, the cross-sectional area of penetrating vessels may increase, and the cerebrovascular resistance and pulsatility index will decline.

Prior studies have clearly demonstrated a relationship between glymphatic impairment and neuroinflammation23,27. There is an age-related decline in penetrating arterial pulsatility, glymphatic CSF influx and ISF solute efflux, and a concomitant increase in the astrocytic inflammatory marker, GFAP27. Similarly, after TBI, there is significant suppression of glymphatic CSF influx, reduced ISF solute clearance, and robust expression of indicators of astrocytosis (GFAP) and microgliosis (IBA1)23. Until this study, however, it has been difficult to link glymphatic stagnation as the cause (rather than the effect) of neuroinflammation. Here we find an immediate reduction of glymphatic flow in the absence of another pathological insult (e.g. TBI), and later, at day 14, a neuroinflammatory response is noted. Consequently, our study shows that glymphatic dysfunction alone can drive a gliotic reaction. Recent work by us and others has defined previously unrecognized vascular channels that link the brain and the skull5,15. These channels fill with neutrophils after stroke and may provide a two-way route for immune cell trafficking between the brain, the meninges, and the skull marrow. Interruption of these channels may additionally contribute to the neuroinflammatory response after craniectomy observed in our study. Future studies may determine whether these vascular channels are reestablished after cranioplasty.

Glymphatic flow recovery independent of cranioplasty may be related to anatomical differences between our model and humans. Mouse dura is much thinner than human dura19, and the thin scar tissue that forms after craniectomy may re-establish intracranial hydrodynamics in a way that pseudo-dura and overlying scalp cannot in humans. Humans are upright, and body position may affect intracranial hydrodynamics as well. The craniectomy in our mouse model, as a percentage of the cranial vault, is much less than was described for either the DECRA or RESCUEicp trial, or than is typical in clinical practice6,20,26. This was a consequence of differences in skull anatomy in mice. Regardless, our work suggests the biologic mechanism by which craniectomy can cause syndrome of the trephined, changes in CSF hydrodynamics, and other sequelae of craniectomy. Future studies with large animals can focus on the relationship between duration of craniotomy, timing of cranioplasty and recovery (“time dose-response”), as well as the effect of craniotomy size on the timing and degree of glymphatic impairment (“size dose-response”).

There were several limitations of our study. Craniectomy was performed in a disease-naïve brain, which does not have a direct clinical analogy (although it begs the question of how all cranial procedures impact glymphatic function in our patients). We chose to isolate the exact relationship between craniectomy and glymphatic circulation without superimposed brain pathology. Having established that both TBI and craniectomy independently result in glymphatic impairment, gliosis, and neurobehavioral deficits23, future studies can evaluate the effect of TBI and craniectomy in combination.

In addition, ex vivo influx data only represents a snapshot in time. Use of time-lapse in vivo two-photon imaging cannot assay brain-wide glymphatic fluxes in both the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. An interesting and surprising finding of this study was that there were suppressed glymphatic fluxes in the contralateral hemisphere, as well as in the white matter and subcortical structures. These observations would have been missed in the small volume of tissue that two-photon imaging can access. Future work will use fluorescence macroscopy to study this system at the whole organ level, but this does not solve the problem of imaging deeper glymphatic fluxes. Contrast agent delivered intrathecally allows MRI imaging of subarachnoid-based CSF fluxes13,24,30,37, but additional development is required to image tissue-level CSF or ISF fluxes with this paradigm.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that opening the skull results in an immediate and widespread impairment in glymphatic function, driving both neuroinflammatory and neurobehavioral changes. Glymphatic recovery precedes reversal of these changes, and cranioplasty accelerates this reversal. What does this mean for our patients? How is glymphatic function altered by calvarial, skull base, or endoscopic approaches? How do CSF diversion procedures, both temporary (external ventricular drainage) and permanent (VP shunting), alter glymphatic circulation? Are there ways to manipulate glymphatic function to benefit our patients? We are familiar with the trope “you ain’t never the same when the air hits your brain”45. Our study suggests that the trope merits serious scientific investigation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dan Xue for expert graphical design used in figures 3A, 4A, and 8.

Financial Support: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health NS078394, RF1AG057575, and AG048769 (MN), and the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation (MN).

Previous Presentations: Portions of this work were presented as proceedings of the 2018 American Association of Neurological Surgeons Annual Scientific Meeting, New Orleans, LA, April 30, 2018.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

References

- 1.Abbott NJ: Evidence for bulk flow of brain interstitial fluid: significance for physiology and pathology. Neurochem Int 45:545–552, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balesteri M, Czosnyka M, Hutchinson P, Steiner LA, Hiler M, Smielewski P, et al. : Impact of intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure on severe disability and mortality after head injury. Neurocrit Care 4:8–13, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bevins RA, Besheer J: Object recognition in rats and mice: a one-trial non-matching-to-sample learning task to study “recognition memory.” Nat Protoc 1:1306–1311, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bor-Seng-Shu E, Hirsch R, Teixeira MJ, Ferreira De Andrade A, Marino R: Cerebral hemodynamic changes gauged by transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in patients with posttraumatic brain swelling treated by surgical decompression. J Neurosurg 104:93–100, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai R, Pan C, Ghasemigharagoz A, Todorov MI, Förstera B, Zhao S, et al. : Panoptic imaging of transparent mice reveals whole-body neuronal projections and skull-meninges connections. Nat Neurosci 22:317–327, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld J V, Murray L, Arabi YM, Davies AR, D’Urso P, et al. : Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med 364:1493–1502, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cserr HF, Cooper DN, Suri PK, Patlak CS: Efflux of radiolabeled polyethylene glycols and albumin from rat brain. Am J Physiol 240:F319–F328, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cserr HF: Physiology of the choroid plexus. Physiol Rev 51:273–311, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daboussi A, Minville V, Leclerc-foucras S, Geeraerts T, Esquerre JP, Payoux P, et al. : Cerebral hemodynamic changes in severe head injury patients undergoing decompressive craniectomy. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 21:339–345, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damkier HH, Brown PD, Praetorius J: Cerebrospinal fluid secretion by the choroid plexus. Physiol Rev 93:1847–1892, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Bonis P, Sturiale CL, Anile C, Gaudino S, Mangiola A, Martucci M, et al. : Decompressive craniectomy, interhemispheric hygroma and hydrocephalus : A timeline of events? Clin Neurol Neurosurg 115:1308–1312, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dujovny M, Fernandez P, Alperin N, Betz W, Misra M, Mafee M: Post-cranioplasty cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamic changes: Magnetic resonance imaging quantitative analysis. Neurol Res 19:311–316, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eide PK, Ringstad G: MRI with intrathecal MRI gadolinium contrast medium administration: a possible method to assess glymphatic function in human brain. Acta Radiol Open 4:1–5, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fodstad H, Love JA, Ekstedt J, Friden H, Liliequist B: Effect of cranioplasty on cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics in patients with the syndrome of the trephined. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 70:21–30, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herisson F, Frodermann V, Courties G, Rohde D, Sun Y, Vandoorne K, et al. : Direct vascular channels connect skull bone marrow and the brain surface enabling myeloid cell migration. Nat Neurosci 21:1209–1217, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holness CL, Simmons DL: Molecular cloning of CD68, a human macrophage marker related to lysosomal glycoproteins. Blood 81:1607–1613, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Honeybul S, Ho KM: Incidence and risk factors for post-traumatic hydrocephalus following decompressive craniectomy for intractable intracranial hypertension and evacuation of mass lesions. J Neurotrauma 29:1872–1878, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Honeybul S, Ho KM: Long-term complications of decompressive craniectomy for head injury. J Neurotrauma 28:929–935, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong J-Y, Suh S-W, Park S-Y, Modi HN, Rhyu IJ, Kwon S, et al. : Analysis of dural sac thickness in human spine — cadaver study with confocal infrared laser microscope. Spine J 11:1121–1127, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG, Timofeev IS, Corteen EA, Czosnyka M, Timothy J, et al. : Trial of decompressive craniectomy for traumatic intracranial hypertension. N Engl J Med 375:1119–1130, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, Plogg BA, Peng W, Gundersen GA, et al. : A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 4:1–11, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Zeppenfeld DM, Venkataraman A, Plog BA, Liao Y, et al. : Cerebral arterial pulsation drives paravascular CSF-interstitial fluid exchange in the murine brain. J Neurosci 33:18190–18199, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iliff JJ, Chen MJ, Plog BA, Zeppenfeld DM, Soltero M, Yang L, et al. : Impairment of glymphatic pathway function promotes tau pathology after traumatic brain injury. J Neurosci 34:16180–16193, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iliff JJ, Lee H, Yu M, Feng T, Logan J, Nedergaard M, et al. : Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast-enhanced MRI. J Clin Invest 123:1299–1309, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joseph V, Reilly P: Syndrome of the trephined. J Neurosurg 111:650–652, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolias AG, Kirkpatrick PJ, Hutchinson PJ: Decompressive craniectomy: past, present and future. Nat Rev Neurol 9:405–415, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kress BT, Iliff JJ, Xia M, Wang M, Wei H, Zeppenfeld D, et al. : Impairment of paravascular clearance pathways in the aging brain. Ann Neurol:1–17, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurland DB, Khaladj-Ghom A, Stokum JA, Carusillo B, Karimy JK, Gerzanich V, et al. : Complications associated with decompressive craniectomy: A systematic review. Neurocrit Care 23:292–304, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazaridis C, Desantis SM, Vandergrift AW, Krishna V: Cerebral blood flow velocity changes and the value of the pulsatility index post decompressive craniectomy. J Clin Neurosci 19:1052–1054, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee H, Xie L, Yu M, Kang H, Feng T, Deane R, et al. : The effect of body posture on brain glymphatic transport. J Neurosci 35:11034–11044, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang W, Xiaofeng Y, Weiguo L, Gang S, Xuesheng Z, Fei C, et al. : Cranioplasty of large cranial defect at an early stage after decompressive craniectomy performed for severe head trauma. J Craniofac Surg 18:526–532, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louveau A, Plog BA, Antila S, Alitalo K, Nedergaard M, Kipnis J: Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J Clin Invest 127:3210–3219, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundgaard I, Lu ML, Yang E, Peng W, Mestre H, Hitomi E, et al. : Glymphatic clearance controls state-dependent changes in brain lactate concentration. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab:1–13, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peng W, Achariyar TM, Li B, Liao Y, Mestre H, Hitomi E, et al. : Suppression of glymphatic fluid transport in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 93:215–225, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plog BA, Nedergaard M: The glymphatic system in central nervous system health and disease: Past, present, and future. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 13:379–394, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plog BA, Dashnaw ML, Hitomi E, Peng W, Liao Y, Lou N, et al. : Biomarkers of traumatic injury are transported from brain to blood via the glymphatic system. J Neurosci 35:518–526, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratner V, Zhu L, Kolesov I, Nedergaard M, Benveniste H, Tannenbaum A: Optimal-mass-transfer-based estimation of glymphatic transport in living brain. Proc SPIE--the Int Soc Opt Eng 9413:1–6, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren Z, Iliff JJ, Yang L, Yang J, Chen X, Chen MJ, et al. : “Hit & Run” model of closed-skull traumatic brain injury (TBI) reveals complex patterns of post-traumatic AQP4 dysregulation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33:834–845, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shih AY, Mateo C, Drew PJ, Tsai PS, Kleinfeld D: A polished and reinforced thinned-skull window for long-term imaging of the mouse brain. J Vis Exp 61:1–6, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soustiel JF, Sviri GE, Mahamid E, Shik V, Abeshaus S, Zaaroor M: Cerebral blood flow and metabolism following decompressive craniectomy for control of increased intracranial pressure. Neurosurgery 67:65–72, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stiver SI: Complications of decompressive craniectomy for traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg Focus 26:1–16, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Szentistvanyi I, Patlak CS, Ellis RA, Cserr HF: Drainage of interstitial fluid from different regions of rat brain. Am J Physiol 246:F835–F844, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thrane VR, Thrane AS, Plog BA, Thiyagarajan M, Iliff JJ, Deane R, et al. : Paravascular microcirculation facilitates rapid lipid transport and astrocyte signaling in the brain. Sci Rep 3:1–5, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Timofeev I, Hutchinson PJ: Outcome after surgical decompression of severe traumatic brain injury. Injury 37:1125–1132, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vertosick FT: When the Air Hits Your Brain: Tales from Neurosurgery. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M, Iliff JJ, Liao Y, Chen MJ, Shinseki MS, Venkataraman A, et al. : Cognitive deficits and delayed neuronal loss in a mouse model of multiple microinfarcts. J Neurosci 32:17948–17960, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang XF, Wen L, Shen F, Li G, Lou R, Liu WG, et al. : Surgical complications secondary to decompressive craniectomy in patients with a head injury: a series of 108 consecutive cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 150:1241–1248, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]