Abstract

Although England/Wales, Italy, and the United States share a common policy of deinstitutionalization, their mental health systems differ considerably. Each country’s civil commitment standards define patient eligibility criteria along one of two primary dimensions-need for treatment or degree of dangerousness. These differential selection criteria result in mental health systems serving different subgroups of the total population. The criteria in England/Wales target older women; in the United States, younger men; and in Italy, a group balanced in age and sex. Implications for the current debate on civil commitment policies are considered.

Although England/Wales, Italy, and the United States share a common policy of deinstitutionalization their mental health systems differ considerably with regard to patient selection and resulting patient mix. Differences appear to derive from prevailing civil commitment standards—the rules governing involuntary detention.

Civil commitment standards in each country are defined by one of two types of eligibility criteria--either need for treatment or degree of dangerousness. Implementing civil commitment standards involves varying degrees of practitioner judgment in admission decision making. Constraints on professional discretion in civil commitment decision making derive from three sources: 1) the breadth of the standard, i.e., the number of different types of people covered by the standard; 2) the precision of the standard—the degree of specificity associated with the standard; and 3) administrative or judicial review of the admission procedure. In this paper, consideration of professional discretion relates primarily to the breadth and the precision of the standard rather than procedural review. This study will show how broader discretionary powers associated with the greater breadth and the lack of precision in the need-for-treatment standard, as opposed to the restricted ,population focus (breadth) and increased precision of the dangerousness standard, have led to very different patient groups in each country. Further, the study will demonstrate that the choice of civil commitment standards reflects the basic social philosophy in each country.

CIVIL COMMITMENT CRITERIA AND PROFESSIONAL DISCRETION IN PATIENT SELECTION

The 1930 Mental Health Act in England/Wales created a system of civil commitment based on the delegation of discretion to the psychiatric profession to determine who was in need of treatment. The Mental Health Act was a move away from the precise “legalistic” criteria of the 1890 law, to an orientation that has prevailed in Britain through revisions in 1954 (1) and 1983. The standard for involuntary detention became “suffering from a mental disorder that would require containment for reasons of health and safety” (2), where the mental health professional defines these circumstances and can choose to serve those individuals the professional believes fall within his or her “direct practice competence.” The Mental Health Act is purposefully vague; it lacks precision.

During the past 25 years, a majority of states in the United States have changed involuntary admission criteria from “in need of treatment due to mental disorder” to “being a danger to oneself or others due to mental disorder.” This change has shifted the emphasis of admission criteria from broad professional discretion (based upon a purposefully vague and broad standard) to a legally specifiable dangerousness standard (3–5)—one that restricts professional discretion by narrowing the breadth of the standard to focus on a particular subpopulation of the mentally ill.

This change of standards in the United States reflects the intent of the courts that found traditional need-for-treatment standards unconstitutional by virtue of their breadth and lack of precision. The courts sought in the dangerousness criterion a more stringent standard commensurate with due process rights (6). Limited empirical research in the United States seems to support the observation that psychiatric decision making under the dangerousness criterion is significantly less discretionary than under the need-for-treatment criterion. While one report indicates that 94% of patients involuntarily admitted to two hospitals under the dangerousness criterion displayed behavior conforming to the standard (7), two comparable studies found that only 31 % and 36%, respectively, of the patients involuntarily admitted to the hospital under a need-for-treatment criterion actually met the statutory description (8). Thus, in the United States, mental health professionals operating under the dangerousness standard seem more constrained to accept those who meet the standard. British professionals, in contrast, can exercise more selectivity as to whom they serve.

PATIENT MIX

A comparison of age and gender distribution rates of first admissions in England/Wales, Italy, and the United States illustrates how the civil commitment standard changes have reshaped the service populations of their respective systems.

Age Distribution Rates and Patient Selection Criteria

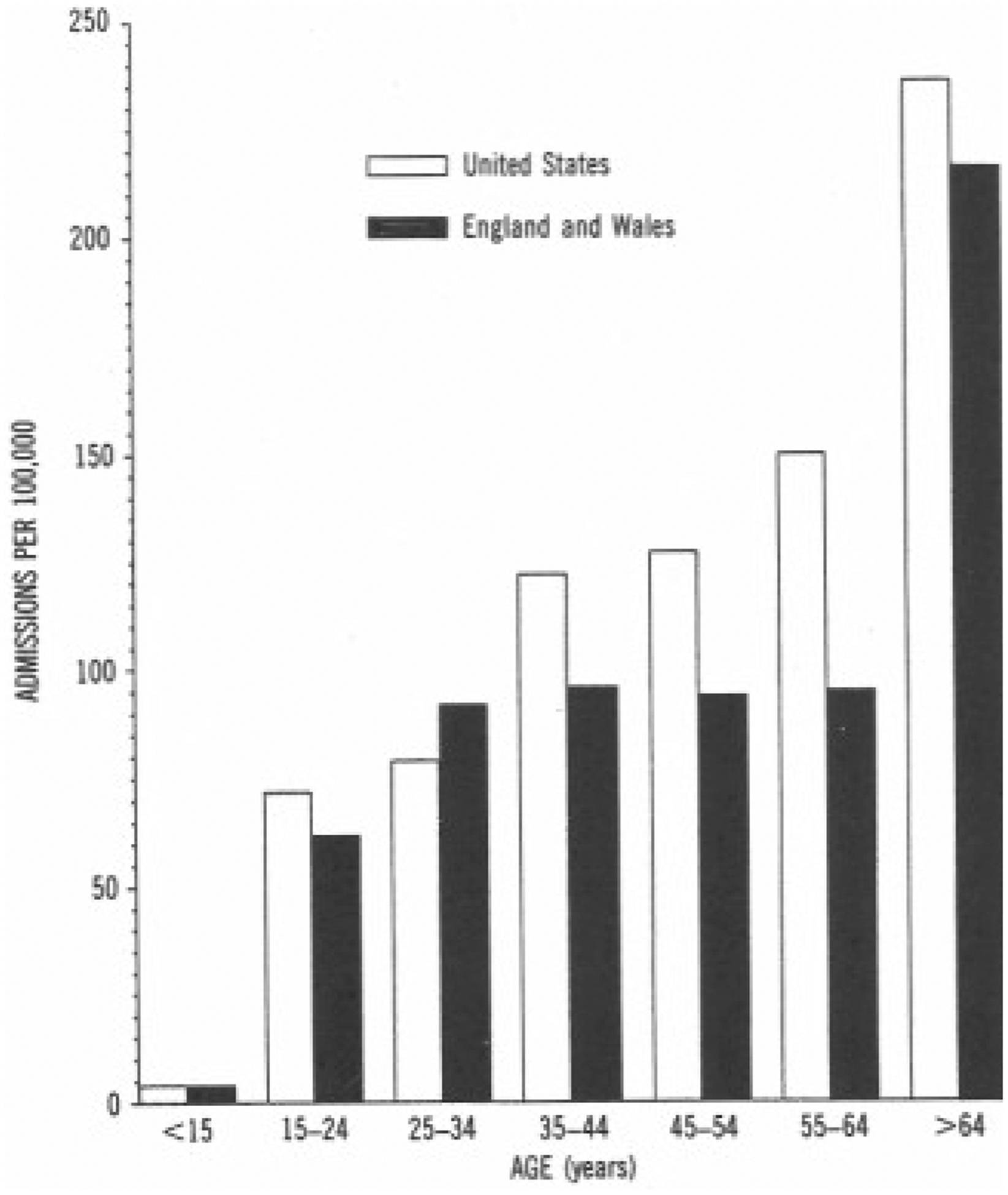

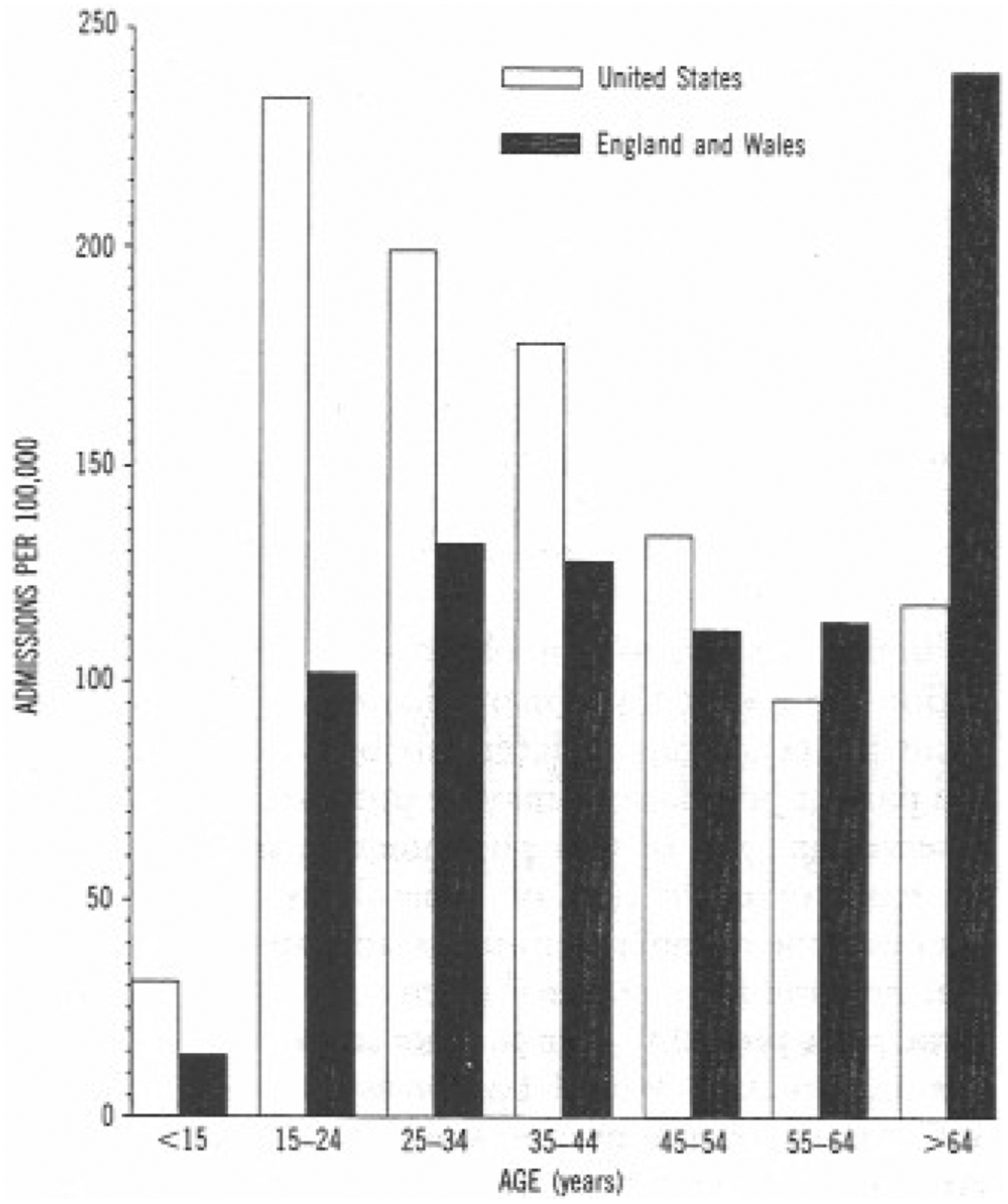

Figure 1 shows the age distribution rates of first admissions per 100,000 for the United States and England/Wales in 1955, when both countries employed the need-for-treatment standard (comparable figures are unavailable for Italy) (9; 10, see also same reports for 1949–1951). The systems appear quite similar, with the exception of a greater emphasis in the United States on patients in their middle years. Figure 2 presents the comparable age distribution for 1980—a period following the United States’ conversion to a dangerousness standard (11, 12). The British system, compared with that of the United States, places an emphasis on serving an older population. The United States, on the other hand, has completely reoriented its inpatient system over the past 25 years, a period paralleling its shift to the dangerousness standard. It has moved from an emphasis on an age group similar to that served in England/Wales to an emphasis on youth.

FIGURE 1.

Age Distribution of First Admissions to State and County Mental Health Facilities in the United States and England/Wales, 1955a

aU.S. data from Kramer (9), data on England and Wales from British Registrar General (10).

FIGURE 2.

Age Distribution of First Admissions to All Inpatient Facilities in the United States and England/Wales, 1980a

aU.S. data from NIMH (11), data on England and Wales from British Department of Health and Social Security (12).

In a comparison of the inpatient first admission graphs in figure 1, it is apparent that the function of inpatient care in the United States and in England/Wales is very different. The decrease in the mentally ill aged in the U.S. mental health system can be attributed to their reclassification and relocation among the frail elderly in nursing home care. However, the replacement of the elderly in mental hospitals by those in the 15- to 24-year-old age group indicates that the current interpersonal environment of inpatient settings, as well as the types of disorders dealt with in the United States and England/Wales, are approaching opposite poles.

The increase in young patients in the United States appears to reflect the dangerousness criterion in that 1) the prevalence of behavior considered dangerous to others is highest in the 15- to 14-year-old group and is lowest in the 45 and older age groups (13), and 2) the prevalence of adolescent suicide and suicide attempts has been increasing at an alarming rate (14).

As in the United States, the prevalence of violent crime in England/Wales is at its height in the 14- to 11-year age group; since 1975 there has also been an increase in the prevalence of violence (15), adolescent suicide, and suicide attempts (16) in England/Wales. However, the prevalence of actual suicides and violent crime in England/Wales is much lower than in the United States. A conservative estimate of the U.S. suicide rate in 1980 for the 15- to 24-year age group was 12.3 per 100,000 (17); in England/Wales, the comparatively conservative 1981 rate was approximately 6.68—i.e., nearly half the U.S. rate (computed from Home Office statistics [18] and adjusted according to Office of Health Economics procedures [16]).

While British rates of suicide and violent crime are lower than U.S. rates for the 15- to 24-year age group, suicide attempts occur with more equal frequency in the two countries (19, 20). There are large numbers of individuals who have attempted suicide and many troubled adolescents receiving services in general hospitals in England/Wales who are not receiving psychiatric help and who therefore are not represented in psychiatric inpatient first admission rates (16, 21–23). Until recently suicide attempts, especially deliberate self-poisoning, have been considered by British psychiatry to be a social problem outside of direct practice competence. In the United States, however, it is precisely this group of patients that commands a major segment of services offered by the mental health care system (14).

Differences in the patient composition of the U.S. and British systems also derive from the proviso in the British Mental Health Act that individuals with psychopathic diagnoses need not be taken unless they are “amenable to treatment.” To the extent that antisocial behavior is used as an indicator of psychopathic disorder, many patients with troublesome profiles may be excluded from the British mental health service at professional discretion. Because antisocial behavior occurs most frequently in the 15- to 24-year age groups, this proviso may partially explain the smaller representation of 15- to 24-year-old patients in the British system.

It would appear that the differences in patient mix between the two countries are a function of the fact that Britain’s civil commitment standard—the need-for-treatment standard—allows for selection of patients on the basis of professional preferences, while the U.S. standard provides more specific guidelines for patient selection. In the former case, the standard controls the patient mix by default to professional discretion; in the latter, by specification.

Gender and Patient Selection Criteria

The importance of professional discretion in the traditional need-for-treatment standard and its restriction in a system structured by the dangerousness criterion are further evidenced by changes in the Italian system. In 1968, as part of law 431, the “Mariotti reform,” Italy allowed its first voluntary admissions to mental hospitals; in 1978 the country eliminated the dangerousness criterion, making compulsory admissions contingent on a finding that care and rehabilitation were necessary and urgently needed (24). The consequence we should expect—given that only a small proportion of women engage in dangerous behavior at any age—is that new admissions to mental hospitals in Italy would change from a group consisting primarily of men to a more evenly balanced group or, as in the English system, a group with more women. Further, the direction of this change should be exactly the opposite of that in the U.S. system, which moved from a need-for-treatment criterion to the dangerousness criterion. Indeed, Pastore et al., in attempting to understand the new Italian service system, observed that a major difference between old and new cases is a greater predominance of women among new cases as opposed to the predominance of men in the past (D.V. Pastore, M. Marsili, A. Debernardi, unpublished paper, 1984). Torre and Marinoni (25) also noted that admission rates in Italy decreased after passage of law 180 but to a greater extent among men than women.

Table 1 compares the limited number of empirical studies available (26–29) on first admissions in northern Italy with gender distribution rates of first admissions·in the United States and England/Wales in the years covered by these studies. (No Italian national statistics on gender or age distribution rates of first admissions are available.) The stability of the English rates, compared to changes indicating a more pronounced emphasis on males in the United States and a change in the opposite direction in the Italian statistics, forms a natural experiment offering some confirmation of the import of civil commitment standards and the degree of professional discretion they embody in determining patient mix. Clearly, systems molded by the dangerousness criterion have a higher proportion of male patients, while the need-for-treatment criterion brings more women into the system.

TABLE 1.

Gender Distribution of First Admissions to Psychiatric Inpatient Facilities in the United States, England and Wales, and Northern Italy, 1946–1985

| Percent of First Admissions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untied Statesa | England and Walesb | Northern Italyc | ||||

| Period | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women |

| 1946–1947 | 52 | 48 | ||||

| 1946–1349 | ||||||

| 1950–1951 | 42 | 58 | ||||

| 1952–1953 | ||||||

| 1954–1955 | 56, | 44 | 42 | 58 | ||

| 1956–1957 | ||||||

| 1958–l959 | ||||||

| 1960–1961 | 56 | 44 | ||||

| 1962–1963 | ||||||

| 1964–1965 | ||||||

| 1965–1967 | ||||||

| 1968–1969 | 60 | 40 | ||||

| 1970–1971 | ||||||

| 1972–1973 | 68 | 32 | 41 | 59 | 62 | 38 |

| 1974–1975 | 67 | 33 | 41 | 59 | ||

| 1976–1977 | 51 | 49 | ||||

| 1973–1979 | ||||||

| 1930–1981 | 68 | 32 | 43 | 57 | 52 | 48 |

| 1982–1983 | 54 | 49 | ||||

| 1984–1935 | 43 | 58 | ||||

First admissions to state and county mental hospitals, 1946–1947, 1954–1955, 1960–1961, and 1972 (9); first admissions to all psychiatric hospitals, 1974–1975 and 1980–1981 (11).

First admissions to all psychiatric hospitals in England and Wales, 1950–1951 and 1954–1955 (10) and 1972–1973,1974–1975, and 1980–1981 (12).

First admissions to all types of psychiatric facilities as estimated by live studies conducted in Matova in 1968–1976 (N=86) (table reports average for 1968–1976) (26), Trieste in 1977 (N = 226) and 1984 (N = 161) (27), Cagliari in 1981 (N = 372) (28), and 36 facilities in northern Italy in 1983 (N = 209) (29).

INTERPRETING CROSS-NATIONAL DATA: ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE

While the standard influences patient mix, it only sets broad boundaries that are modified by administrative and organizational preferences. Its full impact is experienced over many years. Given the difficulty of interpreting cross-national trends and the slow process by which the law effects change, two additional sources of evidence adding credence to my interpretation of the international age and sex variations should be considered.

Secular Trends in the Reporting of Dangerousness Among the Mentally Ill

In the United States before the early 1960s, in the need-for-treatment era, studies of criminal activity by former psychiatric patients, with the general population used as a control, showed that patients had an equivalent amount or somewhat less criminal involvement than the general population. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, when changes in civil commitment standards were occurring, studies showed that criminal involvement by former patients began to exceed that of the general population. Finally, in the late 1970s, with the broad implementation of the dangerousness standard in civil commitment, studies showed that former patients’ rates of criminal involvement were higher than chose of the general population. Rabkin (30) concluded that these observed rate differentials were due to the admission of a greater proportion of mental hospital patients in the late 1970s who had criminal records before their hospitalization and continued their criminal involvements after their release. It would thus appear that the dangerousness criterion is effectively being used to select “dangerous” people into the system.

Further support for the observation that patient selection by civil commitment standards tends to account for crime rate differentials between the general and patient populations may be obtained from Gunn’s observation (31) of this phenomenon in Britain. On the basis of evaluation of general population crime rates and the number of patients admitted to a psychiatric hospital for a criminal offense, he argued that the crime rates probably do not differ in these two groups. This observation would be consistent with expectations for a system that uses a need-for-treatment standard and corresponds to the results of the U.S. studies conducted in the need-for-treatment era.

Broadening of Civil Commitment Standards in Washington State

In 1979 Washington State became one of the first states to reverse the national trend toward more restrictive admissions criteria by broadening its civil commitment law, moving from a clearly defined dangerousness standard to one allowing for a need-for-treatment criterion. In 1980—the year in which the broadened standard came into effect—as compared with 1976 and 1977 (years preceding the change), there was a large increase in the number of total additions to Washington state and county hospitals. This, however, was accompanied by a drop of almost 5% in the proportion of adult additions in the 18- to 24-year-old age group—the population at high risk for dangerousness (Z=5.04, p<0.01, in a comparison of both 1976 to 1980 and 1977 to 1980) (32). (Additions include admissions, readmissions, and returns from extended leave during the reporting year; age distribution of first admission and admission statistics are not available.) Thus, the implementation of a need-for-treatment criterion appears, even in the first year of activity, to have resulted in a reduction in the relative size of the young adult age group. These changes and the observed secular trends in the reporting of dangerousness seem to validate the interpretation of the international age and sex variations in first admissions presented earlier.

During the past 5 years a new and increasingly polarized debate has developed in the United States between the advocates of “holding the line” on the dangerousness standard and the advocates of a return to a need-for-treatment standard. The former group views a return to the need-for-treatment standard as abandonment of the civil rights orientation embodied in the restricted range of decision making imposed by the dangerousness standard. The latter group views the dangerousness standard as inappropriately forcing professionals to treat untreatable patients and forcing them to abandon their commitment to a paternalistic approach to patients (33). The data presented here show that the adoption of either standard represents a preselection of the type of patients who will receive treatment and an altering of the patient mix in the system. With only rudimentary knowledge of how this process occurs, there are at least four factors to consider in understanding such system changes.

Resource Availability

The Washington State results, in contrast to the international data, illustrate how resource availability interacts with civil commitment standards to reshape patient mix. The international data are reported in the context of an effort to reduce utilization of inpatient beds. With declining resources, the civil commitment standard will screen people in a way that results in a system numerically dominated by the selected population. By contrast, the denial of hospitalization to a patient who subsequently murdered two prominent citizens led to a willingness in Washington State to expand inpatient resources. With increasing availability of beds, the civil commitment standard screen will decrease the proportion of ineligible or less desirable groups, although the numbers of individuals in both groups may increase. The standard operates as a means of selective recruitment or outreach.

Restricting Discretion in the Need-for-Treatment Standard

Because the traditional need-for-treatment standard involves the granting of broad discretionary powers to clinical decision makers (6), patient mix could become a reflection of practitioners’ service preferences. Recognizing this and being skeptical with regard to the use of unrestricted discretion by clinicians, advocates of a return to a paternalistic need-for-treatment standard have attempted to operationalize the model’s selection criteria. Their approach, the Stone-Roth model, sets forth five commitment criteria believed to appropriately limit the discretionary powers of the evaluator (33). Since this model has received only simulated testing with patients currently entering the system, and since these simulations have produced different conclusions about the effect of these limits on discretionary admissions, it is difficult to say how this model would influence patient mix (33; S.K. Hoge, G. Sachs, P.S. Appelbaum et al., unpublished data, 1987). Hoge et al.’s simulation (unpublished) indicates, however, that those patients most likely to be excluded from the system in a shift to the Stone-Roth criteria would be those presenting as a danger to themselves and those who have personality disorders—both are groups likely to come from the 18- to 24-year-old men and suicide attempters discussed earlier. It would seem, therefore, that the Stone-Roth criteria reflect the preferences in case mix embodied in the more traditional need-for-treatment standard.

Shaping the Gatekeepers

The civil commitment standard is important in selecting patients at the time of evaluation, i.e., in immediately bringing a change to the patient mix within the facility. The implementation of the standard, however, also sends a message to gatekeepers as to the characteristics of patients who are to be selectively removed from the system. This is especially true in public emergency rooms where police officers are a major source of referrals and are very much attuned to the types of people admitted and released. Decisions of emergency room evaluators have a direct impact upon the work schedule of the beat officers. A beat officer wishing to take a patient to the hospital for evaluation must get someone to cover the beat. The officer must transport the patient—often a round trip of an hour or two—to a psychiatric emergency facility. After having transported a patient who is subsequently turned away, the beat officer becomes very reluctant to continue to transport such patients for evaluation. This process accelerates the change in patient mix attributable to the standard’s selection biases. In effect, the gatekeepers are shaped, in the behavioral sense of the term, to bring in the “appropriate” patients, those patients who will meet the criteria.

Needs-Oriented Versus Rights-Oriented Systems

Culturally, Britain’s need-for-treatment standard is consistent with paternalistic social philosophies prevalent in the welfare state. Similarly, Italy’s move to a paternalistic standard reflects the increasing power of Western European Communism in Italian thinking. Both of these systems lead very easily to a needs-orientation as compared to the “rugged individualism” embodied in U.S. thought—an individualism reflected in rights-oriented programs.

In a consideration of the rights versus needs theme in patient selection, the analogy may be drawn to the value systems of law and medicine, respectively. The legal rights orientation emphasizes the uniqueness of each individual, regardless of worthiness, and advocates equal protection under the law as well as equal access to care. Following this theme, the “patient,” or sometimes “client,” is more active in determining the nature of the help he or she will receive and accept—with the exception of those situations in which the patient’s behavior poses a direct threat to self or the community. In the latter situation the law requires the mental health professional to take action. Thus, in a rights-oriented system, the civil commitment standard constrains professional discretion. In fact, with limited resources and a cultural emphasis on individual responsibility, the U.S. system has become a residual service dealing only with the most difficult people.

The British system, viewed in terms of the medical concept of triage, selects those who not only are in need (as determined by professional evaluation), but who can also benefit most from the limited help available and adapt to existing long-term care facilities without the type of disruption experienced by the U.S. services. This kind of system prevailed in the United States during the 1950s but has bowed to the rights orientation because of the direct challenge to the concept of treatment effectiveness. As former U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger said:

Given the present state of medical knowledge regarding abnormal behavior and its treatment, few things could be more fraught with peril than to irrevocably condition a State’s power to protect the mentally ill upon the providing of “such treatment as will give [them] a realistic opportunity to be cured.” Nor can I accept the theory that a State may lawfully confine an individual thought to need treatment and justify that deprivation of liberty solely by providing some treatment. Our concepts of due process do not tolerate such a “tradeoff.” (34)

Under these circumstances the triage notion breaks down, and the primary arguments for a need-for-treatment criterion allowing for the focus on serving middle-aged and older female patients who are less socially disruptive are: 1) their greater worthiness, 2) their willingness to acquiesce in system norms and cooperate with system procedures, and 3) the fact that other eligible groups are more adequately attended to by other social institutions or are not apparent in the society because of different cultural perspectives.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the limited availability of mental health services and the large pool of people who might qualify for such services, no current national mental health system appears to accommodate all potential users of inpatient care. Analysis of the data available regarding the operation of the civil commitment criteria in England/Wales, Italy, and the United States indicates that it is necessary to understand the health and social services systems of a country as well as its cultural context in order to comprehend the full impact of civil commitment criteria on patient mix. Regardless of this context, however, the substance of the criteria has a clear and specifiable impact on the demographic characteristics of the patient population.

Patient mix or group composition affects treatment strategies, service outcomes, and the social context of inpatient facilities. The mental health system’s lack of responsiveness to the young adult chronic patient was partially a lack of recognition of a change in patient mix. Thus, advocating the choice of a civil commitment standard in the current debate is potentially choosing who will be served, how to serve them, and the types of outcomes and work environments evidenced in inpatient facilities.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Center for International Exchange of Scholars, Western European Regional Research Fulbright Award; NIMH grant MH-37310; and by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The author thanks colleagues in England and Italy for their cooperation and support and Drs. Paul Appelbaum and Margaret Watson for their comments and editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Presented at the 140th annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, Chicago, May 9–14, 1987.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jones K: A History of the Mental Health Services. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mental Health Act, 1983. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segal SP, Wacson MA, Goldfinger SM, et al. : Dangerousness and civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room, I: the assessment of dangerousness by emergency room clinicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45,748–752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Segal SP, Watson MA, Goldfinger SM, et al. : Dangerousness and civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room, II: mental disorder indicators and three dangerousness criteria. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45,753–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segal SP, Watson MA, Goldfinger SM, et al. : Dangerousness and civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room, III: disposition as a function of mental disorder and dangerousness indicators. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45,759–763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt Lessard v, 349 F Supp 1078 (ED Wis, 1972) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Segal SP, Watson MA, Nelson LS: Application of involuntary admission criteria in psychiatric emergency rooms. Social Work 1985; 30,160–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheff TJ: Being Mentally Ill. Chicago, Aldine, 1966 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer M: Psychiatric Services and the Changing Institutional Scene, 1950–1985. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Registrar General: Statistical Review of England and Wales for the Three Years., 1954–1956: Supplement on Mental Health. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1956 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Division of Biometry and Epidemiology: Statistical Printout on Admission and First Admissions. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Mental Health, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health and Social Security: Inpatient Statistics from the Mental Health Enquiry for England, 1982. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarrell EF, Flanagan TJ (eds), Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics., 1984: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice. Washington. DC: US Government Printing Office, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassuk EL, Schoonover SC. Gill AD (eds)’ Lifelines’ Clinical Perspectives on Suicide. New York, Plenum., 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Home Office: Criminal Statistics, England and Wales, 1984. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Office of Health Economics: Suicide and Deliberate Self Harm. London, Office of Health Economics; 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Bureau of the Census: Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1986, 107th ed Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Home Office: Mortality Statistics, England and Wales, 1982. London, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown JH: Suicide in Britain: more attempts, fewer deaths, lessons for public policy. Arch Gen Psychjatry 1979; 36:1119–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissman MM: The epidemiology of suicide attempts. 1960 to 1971. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1974; 30,737–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones DlR: Self-poisoning with drugs: the past twenty years in Sheffield. Br Med J 1977; 1:28–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawton KE: Attempted suicide. Medicine 1983; 10–12 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwab JJ, Warheit GJ, Holzer C: Suicidal ideation and behavior in a general population. Dis Nerv Syst 1971; 33:745–748 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tansella M, De Salvia D, Williams P: The Italian psychiatric reform: some quantitative evidence. Verona, Italy, Isrituto di Psychiatria, Univenitá di Verona, April 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Torre E, Marinoni A: Register studies: data from four areas in northern Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1985; 316,87–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fonranesi F: Il Ricovero Nell’Ospedale Psichiatrico Provinciale di Mantova di Persone Residenti Nel Territorio “Mantova 2 Estero Nord-Est”: Ricerca Epidemiologica Longitudinale Rdariva al Periodo 1939–1975. Padova, Italy, Tesi di Laurea, University Degli Studi Di Padova, 1975–1976 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bertali M: La ‘nuova utenza’, Delle Strutture Psichiatriche Pubbliche di Trieste: Uno Studio di Epidemiologia Descrittiva. Trieste, Italy, Tesi di specialezzazione. Université Degli Studi Di Trieste, 1984–1985 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rudas N, Carpiniello B, Puddu G, et al. : Servizi Psichiatrici Nell’Area Urbana di Cagliari: resultari di una indagine epidemiologica. Neurologia Psichiatria Scienze Unane. Proceedings, Atti Del XXXV Congresso Nazionate Societá, Italiana Di Psichiatria Cagliari, Italy, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gruppo Interdiscaplinare Valutazione Interventi in Psichiatria (GIVIP): Istituto Di Ricerche Farmacologiche, Mario Negri; Milan, Italy, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabkin JG: Criminal behavior and discharged mental patients, Psychol Bull 1979; 86:1–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunn J: Criminal behavior and mental disorder. Br. J Psychiatry 1977; 130,317–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrissey J, Witkin MJ: Trends by State in the Capacity and Volume of Inpatient Services, State and County Mental Hospitals in the United States, 1976–1980. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Monahan J, Ruggiero M, Friedlander HD: Stone-Roth model of civil commitment and the California dangerousness standard. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982; 39,1267–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donaldson O’Connor v, 422 US 563 (1975) [PubMed]