Abstract

Purpose

In the field of forced migration and mental health research, longitudinal studies with large sample sizes and rigorous methodology are lacking. Therefore, the Resettlement in Uprooted Groups Explored (REFUGE)-study was initiated in order to enhance current knowledge on mental health, quality of life and integration among adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway. The main aims of the study are to investigate risk and protective factors for mental ill health in a longitudinal perspective; to trace mental health trajectories and investigate important modifiers of these trajectories and to explore the association between mental health and integration in the years following resettlement. The aims will be pursued by combining data from a longitudinal, three-wave questionnaire survey with data from population-based registries on education; work participation and sick-leave; healthcare utilisation and drug prescription. The goal is to incorporate the data in an internationally shared database, the REFUGE-database, where collaborating researchers may access and use data from the study as well as deposit data from similar studies.

Participants

Adult (≥18 years), Syrian citizens who arrived in Norway as quota refugees, asylum seekers or through Norway’s family reunion programme between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017. Of the initial 9990 sampled individuals for the first wave of the study (REFUGE-I), 8752 were reached by post or telephone and 902 responded (response rate=10.3%).

Findings to date

None published.

Future plans

The REFUGE-cohort study will conduct two additional data collections (2020 and 2021). Furthermore, questionnaire data will be linked to population-based registries after all three waves of data collection have been completed. Registry data will be obtained for time-periods both prior to and after the survey data collection points. Finally, pending ethics approval, we will begin the process of merging the Norwegian REFUGE-cohort with existing datasets in Sweden, establishing the extended REFUGE-database.

Trial registration number

ClincalTrials.gov Registry (NCT03742128).

Keywords: mental health, epidemiology, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study features a large sample of both male and female adult refugees from Syria who were resettled in a high-income country between 2015 and 2017.

Study participants were selected through random sampling from a population-based source population identified using Norway’s National Registry—that is, all refugees from Syria residing in Norway who met inclusion criteria had equal probability of selection.

The study will use a three-wave survey design which will enable longitudinal tracking of self-reported mental health and other key measures.

The study will link data from the three-wave, questionnaire survey to data in Norway’s large, population-based registries on education, work participation and sick-leave, healthcare utilisation and drug prescription; as well as to other datasets/data sources within the European Union.

Initial data collection yielded a low-response rate, despite extensive recruitment efforts.

Introduction

The adversities of forced migration make the current population of more than 70 million forcibly displaced people especially vulnerable.1 Here, the concept of ‘vulnerability’ refers to refugees’ heightened exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTEs) such as torture, war and/or violence-related traumas prior to or during forced migration, as well as experiences of post-migration socioeconomic hardships and social isolation. Together, these risk factors create a vulnerability that constitutes a profound risk for mental ill health and reduced quality of life with potential long-lasting effects.2–4

Given the aforementioned high burden of mental ill health in refugee populations and the centrality of functional impairment in the diagnostic frameworks for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression in the main diagnostic manuals,5 6 few studies have looked at integration in relation to mental health within refugee populations. The studies available show that general health problems, as well as symptoms of PTSD and depression, are adversely associated with economic and social integration,7 8 with one study finding mental health to be a mediator between post-migration stressors and integration.9 Still, longitudinal studies with large sample sizes and rigorous methodology are lacking and the sociopolitical controversy that is linked to the topic of refugee health often influences the measures and investigative methods used.10 Therefore, studies that bridge these gaps are warranted in order to better understand the resettlement stressors and the mental health burden of refugees resettled in a host country in order to inform policy and practice.

Accordingly, the Resettlement in Uprooted Groups Explored (REFUGE)-study was initiated in order to enhance current knowledge on mental health and quality of life among adult refugees from Syria resettled in Norway following the 2011 outbreak of the civil war in Syria. The main aims of the study are to investigate risk and protective factors for mental ill health in a longitudinal perspective; to trace mental health trajectories and investigate important modifiers of these trajectories and to explore the association between mental health and integration in the years following resettlement. This will be done through a planned longitudinal, three-wave survey design linked to population-based registries in Norway on education; work participation and sick-leave; healthcare utilisation and drug prescription.

A broader, secondary aim is to extend the REFUGE-study beyond Norway’s borders, through collaboration between the REFUGE-study group in Norway and partner institutions in Sweden and the UK, forming the REFUGE-consortium. This work, pending ethics approval, will include setting up and servicing a shared database in order to harness the research potential that lies within the existing datasets on resettled refugees from Syria in Norway and Sweden (N>4500).

A tertiary, long-term goal is to further expand the REFUGE-database by encouraging researchers in other countries to complete similar, nation-wide data-collections that can be added to the existing database. In turn, given the extensive number of included participants, the REFUGE-database will have ample opportunities to provide unique cross-country, intersectional, comparative analyses that can provide robust explanatory models of refugees’ health and social outcomes, in turn informing social policy and practice.

At the time of writing this cohort profile, the first wave of the three-wave survey design has been completed.

Cohort description

Setting

The study is set in Norway, a high-income country, with a population of 5.3 million people.11 Approximately 4.5% of the Norwegian population has a refugee background.12 The Directorate of Immigration (UDI) is the central agency in the Norwegian immigration administration. UDI facilitates lawful immigration and administrates applications for residency and citizenship, including asylum applications.13 Since its onset in 2011, the civil war in Syria has forced more than 6.5 million Syrian citizens to flee the country as refugees, of which an estimated 1 million have reached Europe, excluding Turkey.14 15 At the time of primary data collection, forced migrants from Syria therefore constituted the largest group of newly resettled refugees and asylum-seekers in Norway.

Eligibility

The source population for the REFUGE-study cohort was defined by the following three criteria: potential participants had to be (1) Syrian citizens who arrived in Norway as either a resettlement refugee (quota refugee), an asylum seeker, or through Norway’s family reunion programme, (2) granted permanent or temporary residency and registered with an address in Norway between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017 and finally (3) 18 years of age or older at the time the sample was drawn from the source population.

These criteria were sent to the Norwegian National Registry (NNR) who generated a list of potential participants (N=14 350) from their database consisting of all individuals residing in Norway at that time. A simple, random, equal probability sample of 9990 Syrian citizens was then drawn in August 2018.

Study preparation and promotion

In initial stages of development, approximately a year before the commencement of the data collection, an early version of the questionnaire was tested in a reception centre. Arabic speaking asylum seekers filled out the survey and participated in focus groups with the aim of testing and tailoring the questionnaire for length, comprehension and cultural sensitivity. Several amendments to the questionnaire then followed as a result of the feedback obtained in these focus groups. Findings from this preliminary stage also prompted the creation of a user reference-group, consisting of six Syrians living in Norway. This user reference-group served as an advisory board throughout the planning, development and implementation of the study.

Additionally, prior to data collection, a number of strategies were employed in order to inform potential participants about the study and boost participation. Key persons within the community were identified and contacted in order to discuss ways to explain and promote the study through social media and other channels. Based on input from these sources, several short, animated movies were made in Arabic in order to explain why the study was being undertaken, what participation entailed and how key issues in research, such as informed consent, confidentiality, data handling and privacy rights, would be handled. REFUGE web and Facebook pages were also created in both Arabic and Norwegian, conveying the same information as the movies, in more detail. The Facebook page, with Q&A, was continuously supervised and moderated by a native Arabic speaker.

In order to reach a wider range of potential participants, in-person and paper-based dissemination of information also took place. Information and Q&A sessions at Adult Education centres in Norway’s larger cities were held by the REFUGE team members, including an Arabic interpreter from Syria who was involved in the study from the beginning. Information about the study was also sent to local community refugee centres throughout Norway. These centres work with refugees on a daily basis, assisting and counselling them on various matters related to the integration process into Norway.

Sampling

The first wave of the REFUGE-study (REFUGE-I) was launched at the end of November 2018. Each of the 9990 sampled Syrian refugees were sent an envelope containing the study questionnaire, a cover letter in Arabic and a prepaid return envelope. The cover letter explained the purpose and voluntary nature of the study, what participation entailed and issues surrounding confidentiality and data handling. It also included a space for willing participants to provide written informed consent in the form of a signature. Moreover, due to the sensitive nature of some parts of the questionnaire, the cover letter explicitly stated that ‘some questions in the questionnaire might be difficult to answer, cause slight discomfort or might bring up difficult memories from your past or flight to Norway’. It also included contact details to clinical back-up in the form of a psychiatrist at Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies, stating that participants could contact this person in order to receive information and support in accessing professional medical help in Norway. Out of hours and emergency service contact details were also included.

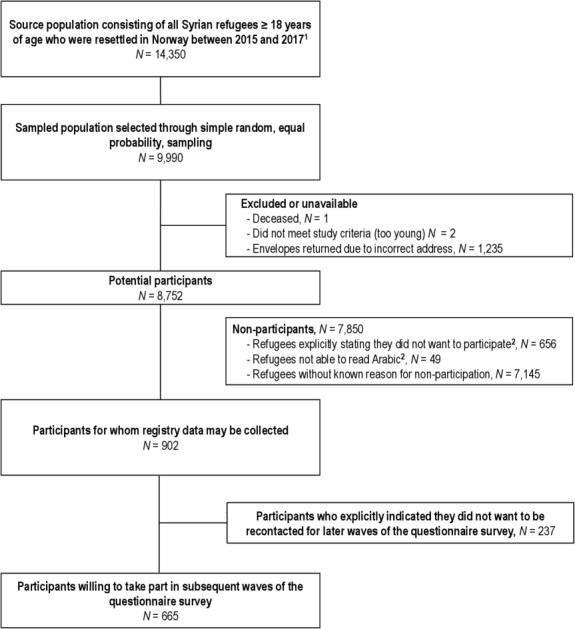

The address list provided by the NNR included 1235 addresses where the addressee was either not found or could not be reached. These potential participants were never found and therefore excluded from the study. Current rules for conducting research surveys in Norway prohibit more than one reminder being sent out to non-responders to encourage participation. Based on a small pilot project testing the use of telephone reminders with Arabic speaking personnel conducted on 530 non-responders in the sample, it was decided that telephone reminders would be used for all non-responders with an available telephone number (N=5675). Telephone contact was made with less than half of this group (N=2087). Online supplementary table S1 summarises the answers given by this group when asked to participate. The telephone reminders were conducted in late March and early April 2019. A postal reminder which included the questionnaire, the cover letter with informed consent and a prepaid return envelope was also sent out to non-responders who were not reached via telephone (N=5000). The postal reminder was sent out in early June 2019. Figure 1 summarises the flow of participants through REFUGE-I, and table 1 provides comparative statistics on participants in REFUGE-I vs the source and sample population. Of the initial 9990 sampled individuals, 8752 were reached either by post or telephone and 902 returned the questionnaire (response rate=10.3% if non-contacts are excluded). Of the 902 responders, 665 (73.2%) were willing to take part in later waves of the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants through the study. 1Refugees were either resettlement/quota refugees; asylum seekers who were granted asylum in Norway; or individuals coming through the programme ‘family immigration with a person who has protection (asylum) in Norway’. The source population was identified through the Norwegian National Registry. 2Information was obtained when non-responders were contacted during the telephone reminder.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants vs the source and sample populations

| Source population | Sample population | Participants | Participants willing to take part in subsequent surveys | |

| N=14 350 | N=9990 | N=902 | N=665 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 5117 (35.7) | 3552 (35.5) | 320 (35.5) | 236 (35.5) |

| Male | 9233 (64.3) | 6446 (64.5) | 582 (64.5) | 429 (64.5) |

| Age* | ||||

| 18–29 | 6135 (42.8) | 4265 (42.7) | 197 (21.8) | 148 (22.2) |

| 30–39 | 4769 (33.2) | 3315 (33.1) | 310 (34.4) | 218 (32.8) |

| 40–49 | 2263 (15.8) | 1604 (16.0) | 230 (25.5) | 173 (26.0) |

| 50–64 | 1034 (7.2) | 721 (7.2) | 145 (16.1) | 112 (16.9) |

| >64 | 149 (1.0) | 95 (1.0) | 20 (2.2) | 14 (2.1) |

| Civil status* | ||||

| Unmarried | 5879 (41.0) | 4047 (40.5) | 236 (26.1) | 176 (26.5) |

| Married | 7873 (54.8) | 5545 (55.5) | 595 (66.0) | 433 (65.1) |

| Other† | 598 (4.2) | 398 (4.0) | 71 (7.9) | 56 (8.4) |

| Year granted residency in Norway | ||||

| 2015 | 2993 (20.8) | 2081 (20.8) | N/A‡ | N/A‡ |

| 2016 | 7513 (52.4) | 5267 (52.7) | ||

*Age and civil status for the two participating groups was based on participants’ answers in the questionnaire.

†Includes widow(er), separated, divorced.

‡Individual-level data on the year residency was granted was not provided by the Norwegian National Registry.

bmjopen-2019-036101supp001.pdf (37KB, pdf)

According to the original plan registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, data collection was planned to run for about 6–8 weeks. However, due to a very low-response rate at the time of the planned closing date in mid-January 2019, the study was extended and the final closing date was in early September 2019.

The administration and logistics of the survey was handled by the research and consulting firm, Ipsos, which has extensive experience with and infrastructure for these types of surveys. Ipsos is also responsible for securely storing participants’ Norwegian identity numbers so that longitudinal tracking of individuals and linking to registry data is possible. The identity numbers are unknown to all researchers involved.

Methods

Quantitative measures

Three waves of questionnaire surveys are planned for the REFUGE-study (REFUGE-I, II and III). Collection for REFUGE-I has already been completed as described above. REFUGE-II and III are scheduled to be carried out roughly 1 and 2 years after REFUGE-I, respectively. The questionnaire used will be very similar for all three waves of the study. Key variables are highlighted in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of key measures used in the longitudinal, three-wave, questionnaire survey

| Measure used* | Comments | |

| Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Harvard Trauma Questionnaire | The first 16 items on trauma symptoms in section IV will be used |

| Symptoms of anxiety and depression | Hopkins Symptom Checklist | The first 10 of the total 25 items will be used to measure symptoms of anxiety and the last 15 to measure symptoms of depression |

| Quality of life | WHO Quality of Life Assessment | The scale consists of 26 items and all will be included |

| Somatic pain | Questions adapted from the Tromsø Study | 10 questions will be used, 5 concerning muscle/joint pain and 5 concerning more general somatic pain |

| Perceived general health | European Social Survey | Two items from the scale will be included |

| Sleep difficulties | The Bergen Insomnia Scale | The scale consists of six items and all will be included |

| Potentially traumatic eventsbefore the flight from Syria (pre-migratory PTEs) | The Refugee Trauma History Checklist (RTHC) | The scale consists of eight items and all will be included |

| Potentially traumatic events during the flight from Syria (peri-migratory PTEs) | RTHC | The scale consists of eight items and all will be included |

| Post-migration stressful experiences | Post-Migration Stress Scale | The scale consists of 24 items and all will be included |

| Social support | Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) Social Support Inventory (ESSI) | The first six items of the scale will be included |

*Further information on the measures used can be found in the ClinicalTrial.gov database where the study is registered (NCT03742128).

Other important measures in the questionnaire include an item regarding the re-experiencing of traumatic events or intrusive memories, which asks whether the participant experiences this, how often and how distressing it is. Another item asks about the daily effects of chronic physical illness, disability, infirmity or mental health problem(s). Finally, as an addition to the ENRICHD Social Support nventory Inventory (ESSI), three items have been included to assess how easily the respondent can get help from neighbours, how many people the participant can count on when serious problems occur and how much concern people show in what the respondent is doing.

Background and sociodemographic variables

Important background and demographic variables include: gender, age, marital status, number of children, refugee status on arrival (ie, asylum seeker, quota refugee, family reunion or other), whether the participant fled Syria alone or with a partner, family and/or friends, whether other family members had already settled in Norway prior to refugee’s arrival in the country, time elapsed between when a participant fled Syria and arrived in Norway and time in Norway prior to participating in the study. Tables 3 and 4 provide descriptive statistics on participants on the aforementioned variables from the first wave of data collection. The number of participants with missing values across variables can be interpreted from the table (applies for all tables). Additional sociodemographic data collected include: smoking; alcohol and drug use; employment status (Do you currently hold paid employment in Norway? Yes/No); job satisfaction; self-reported competence in English and Norwegian language and years of education completed (How many years of schooling do you have? No education/1–5 years/6–9 years/10–12 years/more than 12 years). Further details on the scales used, their psychometric properties and how variables will be handled in analyses can be found in the ClinicalTrials.gov database.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics on participating refugees from Syria

| Participants, N=902 | Participants willing to take part in longitudinal questionnaire survey, N=665 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number of children | ||

| I do not have children | 271 (31.6) | 213 (33.5) |

| 1 | 63 (7.4) | 44 (6.9) |

| 2 | 125 (14.6) | 86 (13.5) |

| 3 | 139 (16.2) | 103 (16.2) |

| 4 | 101 (11.8) | 78 (12.3) |

| 5 | 77 (9.0) | 53 (8.3) |

| 6 or more | 81 (9.5) | 59 (9.3) |

| Total | 857 (100.0) | 636 (100.0) |

| Education | ||

| 9 years or less | 394 (44.7) | 281 (43.0) |

| 10–12 years | 158 (17.9) | 116 (17.8) |

| More than 12 years | 330 (37.4) | 256 (39.2) |

| Total | 882 (100.0) | 653 (100.0) |

| Refugee status on arrival | ||

| Asylum seeker | 454 (52.5) | 325 (51.0) |

| Quota refugee | 273 (31.6) | 209 (32.8) |

| Family reunion | 133 (15.4) | 100 (15.7) |

| Other | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) |

| Total | 864 (100.0) | 637 (100.0) |

| Arrived in Norway … | ||

| … alone | 247 (28.1) | 182 (28.0) |

| … with friends, but no family | 56 (6.4) | 43 (6.6) |

| … with family | 576 (65.5) | 425 (65.4) |

| Total | 879 (100.0) | 650 (100.0) |

| Family member previously settled in Norway | ||

| No | 594 (68.3) | 440 (68.4) |

| Yes | 276 (31.7) | 203 (31.6) |

| Total | 870 (100.0) | 643 (100.0) |

| Length of flight* | ||

| Less than 3 months | 165 (33.7) | 124 (33.9) |

| 3–12 months | 61 (12.4) | 42 (11.5) |

| 1–2 years | 59 (12.0) | 43 (11.7) |

| t2–3 years | 77 (15.7) | 56 (15.3) |

| More than 3 years | 128 (26.1) | 101 (27.6) |

| Total | 490 (100.0) | 366 (100.0) |

| Residency time in Norway† | ||

| Less than 2 years | 104 (16.8) | 83 (17.9) |

| Between 2 and 3 years | 151 (24.4) | 120 (25.9) |

| Between 3 and 4 years | 289 (46.7) | 209 (45.1) |

| More than 4 years | 75 (12.1) | 51 (11.0) |

| Total | 619 (100.0) | 463 (100.0) |

*Estimated through the number of days elapsed between a refugee reportedly left Syria and arrived in Norway.

†Estimated through the number of days elapsed between a refugee reportedly arrived in Norway and the date he/she returned the questionnaire.

Table 4.

Potentially traumatic experiences prior to and during the flight from Syria among participants

| Participants | Participants willing to take part in longitudinal survey | ||

| N=902* | N=665* | ||

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Before you left your home, have you personally faced any of the following situations or events | |||

| War at close quarters | No | 41 (4.7) | 31 (4.8) |

| Yes | 840 (95.3) | 618 (95.2) | |

| Forced separation from family or close friends | No | 324 (40.3) | 235 (39.8) |

| Yes | 480 (59.7) | 355 (60.2) | |

| Loss or disappearance of family member(s) or loved one(s) | No | 287 (35.3) | 213 (35.5) |

| Yes | 526 (64.7) | 387 (64.5) | |

| Physical violence or assault | No | 554 (70.5) | 400 (69.3) |

| Yes | 232 (29.5) | 177 (30.7) | |

| Witnessing physical violence or assault | No | 304 (36.9) | 203 (33.5) |

| Yes | 520 (63.1) | 403 (66.5) | |

| Torture | No | 567 (72.8) | 410 (71.6) |

| Yes | 212 (27.2) | 163 (28.4) | |

| Sexual violence | No | 710 (93.3) | 518 (92.7) |

| Yes | 51 (6.7) | 41 (7.3) | |

| Other frightening situation(s) where you felt your life was in danger | No | 103 (12.0) | 74 (11.7) |

| Yes | 754 (88.0) | 561 (88.3) | |

| After you left your home, during your flight, have you personally faced any of the following situations or events | |||

| War at close quarters | No | 408 (49.3) | 310 (50.7) |

| Yes | 420 (50.7) | 302 (49.3) | |

| Forced separation from family or close friends | No | 412 (52.5) | 298 (51.5) |

| Yes | 373 (47.5) | 281 (48.5) | |

| Loss or disappearance of family member(s) or loved one(s) | No | 422 (53.8) | 312 (53.6) |

| Yes | 362 (46.2) | 270 (46.4) | |

| Physical violence or assault | No | 638 (83.6) | 467 (83.5) |

| Yes | 125 (16.4) | 92 (16.5) | |

| Witnessing physical violence or assault | No | 566 (72.6) | 405 (70.7) |

| Yes | 214 (27.4) | 168 (29.3) | |

| Torture | No | 657 (86.8) | 481 (87.1) |

| Yes | 100 (13.2) | 71 (12.9) | |

| Sexual violence | No | 722 (97.3) | 529 (97.2) |

| Yes | 20 (2.7) | 15 (2.8) | |

| Other frightening situation(s) where you felt your life was in danger | No | 350 (42.8) | 258 (42.9) |

| Yes | 468 (57.2) | 344 (57.1) | |

*Not all participants answered all items, therefore, the total number of answers for a given item may be less than 902 and 665 for the two groups, respectively.

Integration

Previous research has highlighted that active participation in social contexts promotes mental health, quality of life and beneficial health behaviours.16–18 The REFUGE-study approaches integration in agreement with the primary domains suggested by Ager and Strang,19 which are: employment and labour market, school and education attainments, housing, and health and healthcare. Furthermore, and in line with suggestions by Castles et al20 and Niemi et al,21 we consider civic and social participation/social exclusion to be central indicators of refugees’ access to and active involvement in important spheres of the host societies, and these markers thus indicate a central component of social capital.22

Congruent with the domains of integration suggested by Ager and Strang, the study will use data from the Norwegian national registries in order to measure integration for consenting participants. Specifically, the study plans to obtain data from the National Education Database which contains data on educational participation and achievements; the Norwegian registries on employment and sick-leave which contain data on employment and doctor-certified sick-leave; the Norwegian Patient Registry and the Norwegian Registry for Primary Health Care which contain data on the utilisation of the healthcare system and, finally, the Norwegian Prescription Database which contains data about dispensed drugs. All of the registries contain individual-level data, and the study intends to merge a participant’s longitudinal survey data with that participant’s registry data at in order to investigate how mental health is associated with these measures of integration.

Integration will also be investigated through the questionnaire data. Social integration is explored through measures of post migratory stress (eg, ‘often felt excluded or isolated in the Norwegian society’, ‘often being unable to buy necessities’), social support (ESSI) and quality of life. Furthermore, the questions on how easily the participant can get help from neighbours; how many people the participant can count on when serious problems occur and how much concern people show in what the participant is doing will also be used as measures of integration. In the coming data collection waves, a scale measuring social participation will also be included. This scale will be incorporated both in the quantitative part of the study and as a specific topic within the planned qualitative interviews and focus groups.

Analysis

The study’s registration in the ClinicalTrials.gov database presents detailed analytic plans for the first phase of the REFUGE-study (REFUGE-I). Broad analytic questions to be investigated in the later phases of the REFUGE-study include: (1) what are important risk and protective factors for mental ill health; (2) what are the mental health trajectories and which factors appear to impact these trajectories; (3) how is mental health associated with the measures of integration used in the present study and what are important mediators and modifiers in the relationship between mental health and integration.

Qualitative measures

In addition to the quantitative aspect of the REFUGE-study, qualitative analyses are also planned for future waves of the study, comprising interviews and focus group sessions. Questions regarding participation and non-participation will be included in interview guides. Further themes for the interview and focus group guides are in development, and directions will be refined as further findings emerge from the existing quantitative dataset.

Patient and public involvement

The REFUGE-study was supported throughout the development process by members of the community. Focus groups were held in the early stages of development in order to tailor the questionnaire, and a user reference group was created in order to act as an advisory group, providing insight during the planning, development and implementation stages. Community members were also involved in the recruitment process, providing insight and advice on the dissemination of information about the study through social media.

Findings to date

The first wave of data collection in Norway has been completed. At the time of writing, no findings have been published.

Strengths and limitations

The REFUGE-study has several important strengths, both in terms of methodology, and in value of the resulting data. First, the study population was randomly selected from a large source population consisting of all adult refugees from Syria residing in Norway who met the study’s eligibility criteria, obtained from the NNR. In comparison, many of the previous studies on mental health in refugee populations rely on convenience sampling. Further, the use of a three-wave longitudinal survey design will allow for better exploration of cause–effect relationships between variables in the study, than purely cross-sectional data. In addition, research on the association between refugee mental health and integration is scarce. By linking longitudinal questionnaire data to registry data on education-related, work-related and health-related parameters, the study could make important contributions to the dearth of evidence on this topic. Also, combining self-report data with registry data from well-established national registries may reduce common method bias. Research on refugee mental health to date relies heavily on self-report data. A further strength of the study is that most of the key variables are measured using well-documented and validated scales. Review articles on refugee mental health frequently highlight the large degree of variance in terms of methods used and call for increased focus on methodological issues. Finally, the close collaboration between the REFUGE-study group in Norway and its main collaborating partner, the Red Cross University College in Sweden, will offer ample opportunities to compare Syrian refugee populations in two different countries, as both projects use similar measures and have agreed to collaborate on and combine datasets.

An important potential weakness of REFUGE-I is that less than 11% of the sampled population participated in the study. This could lead to selection bias problems. As can be seen from table 1, participants are very similar to the source and sample population in terms of gender, though the proportion of young and unmarried refugees are notably smaller in the participating group. Online supplementary table S2 shows that the geographical distribution across Norway’s 18 counties was very similar for participants and the sample population. In terms of residency status, participants had the same proportional breakdown as the sample population: 95% had temporary residency in Norway at the time of the survey and 5% had permanent residency (result not shown in tables). In order to further explore selection bias, we investigated whether there were any trends across demographic and background variables in terms of when the surveys were filled out and returned. Given that the survey was open for 9 months, exploring the timing of participation may give some indication of different groups’ willingness to participate, and, by extension, suggest which groups may be over-represented and under-represented among participants. While the most common reason for non-participation was unwillingness, a potentially significant contributing factor to the low participation rate may be the presence of low literacy rates within the sampled population. As shown in figure 1, 49 participants stated an inability to read Arabic to explain non-participation, and it is conceivable that this was the case for a number of sampled individuals who failed to return the survey. Regrettably, current ethical laws in Norway do not allow for an online-based questionnaire where Arabic voice-over could be used. Therefore, potential participants with low reading and writing proficiency regrettably were effectively excluded.

Online supplementary table S3 shows the distribution of demographic variables across four different time-periods of participation (ie, the 9-month period the survey was open was divided into four shorter periods), and online supplementary table S4 shows the distribution across background characteristics related to refugee status and history. Differences in distributions across time-periods were tested with χ2 test of equal proportion. As can be seen from the tables, there was weak or no evidence that the timing of participation was related to demographic and/or background variables with three exceptions. First, there was very clear evidence that residency time in Norway was negatively associated with early participation—that is, the longer a refugee’s residency time in Norway, the less likely (s)he was to participate in the first time-periods following study launch (p<0.001), relatively speaking. There was also very strong statistical evidence (p<0.001) that pre-migratory stress was associated with the timing of participation, though the underlying trend was not easily interpretable. Refugees with the highest number of pre-flight potentially traumatic events were more likely to participate in the early periods after study launch (relatively speaking). This was not true, however, for the refugee group with the second to most pre-flight potentially traumatic events. Finally, there was moderate evidence that refugee status on arrival was association with the timing of participation (p=0.01), though no clear underlying pattern was evident.

Another limitation of the present study is the survey design used to attain prevalences of depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms. Short-form questionnaires, while efficient, do not capture all aspects of the measured constructs. Additionally, recent studies have suggested that when self-report measures are used, resulting prevalences tend to be higher than when using diagnostic interviews.23 24 However, the questionnaires used in the current study to measure PTSD, anxiety and depression have been validated for use within the studied population and their use allows for many more participants to be reached, improving the generalisability of the findings.

Perhaps the most significant learning opportunity provided by the present study thus far has been the challenging recruitment process. Although extensive recruitment efforts were employed, the participation rate for REFUGE-I was just above 10%. As noted previously, methods to boost recruitment involved the utilisation of contacts within the community, dedicated Facebook and web pages in Arabic, and Q&A sessions held at Adult Education centres in Norway’s major cities, as well as the dissemination of information about the project online through purpose-built, animated videos and newsletters. Researchers aiming to gather data from similar populations would do well to ensure that sufficient time and resources are dedicated to the recruitment phase of the study.

Future plans

The REFUGE-cohort study will conduct a second wave of data collection in 2020. A third wave of data collection is planned in 2021, pending funding. Furthermore, we plan to link questionnaire data to Norwegian registry data after all three waves of data collection have been completed. Registry data will be obtained for time-periods both prior to and after the three-wave survey. Primary and secondary objectives with detailed plans for analyses for studies involving registry data will be registered at ClinicalTrials.gov prior to obtaining the registry data, so that true hypothesis-testing studies from the REFUGE-cohort are distinguishable from more exploratory and data-driven studies. Finally, pending ethics approval, we will begin the process of merging the Norwegian REFUGE-cohort with existing datasets in Sweden, creating the REFUGE-database.

Parallel to completing the survey data collection, data-merging and registry data obtainment, we aim to publish papers in accordance with our pre-registered publication plan at ClinicalTrials.gov.

Collaboration

We welcome potential collaboration with other research groups. Interested researchers should contact the REFUGE research group for collaboration and knowledge-sharing. Locally collected data can then be added to the REFUGE-database. Reference estimates (eg, prevalence, incidence and associations) can then be continuously updated and made available to researchers abiding by the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation laws and regulations. In addition, the REFUGE-database will also include data obtained through Scandinavian social and health registries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would especially like to thank all participating refugees and asylum-seekers for taking part in both the main study and preparatory stages of the project. The authors would also like to thank the reference group for their valuable comments and suggestions along the way. Finally, we would like to give special thanks to our trusted Arabic interpreter/translator for excellent work throughout the project period.

Footnotes

Contributors: AN, PC, FS, AA and ØS contributed to the conception of this article. AN, PC, FS, AA and ØS were involved in manuscript writing and revision. AN and ØS were involved in data analysis and data presentation. All authors read, contributed substantially to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The REFUGE-study was funded by the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies. No external funding was received.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All procedures concerning the selection and recruitment of participants, including consent procedures, were approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC)—Region South East (A) in Norway. Reference number 2017/1252.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request. Deidentified participant data will be made available for reuse upon reasonable request pending ethics approval, compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and discretion of the research group with regard to the prospective research project proposal. Requests should be send to refuge@nkvts.no. Additional information regarding the scales used, statistical analysis plans and future data collection is available through ClinicalTrials.gov.

References

- 1.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees UNHCR global trends 2018. UNHCR. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html [Accessed 2 Mar 2020].

- 2.Steel Z, Chey T, Silove D, et al. Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2009;302:537–49. 10.1001/jama.2009.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall GN, Schell TL, Elliott MN, et al. Mental health of Cambodian refugees 2 decades after resettlement in the United States. JAMA 2005;294:571–9. 10.1001/jama.294.5.571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Priebe S. Public health aspects of mental health among migrants and refugees: a review of the evidence on mental health care for refugees, asylum seekers and irregular migrants in the who European region. World Health Organization, 2016. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=Y_hQMQAACAAJ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed Washington, DC: APA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO International classification of diseases, 11th revision (ICD-11). Available: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [Accessed 5 Nov 2019].

- 7.de Vroome T, van Tubergen F. The Employment Experience of Refugees in the Netherlands. Int Migr Rev 2010;44:376–403. 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00810.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schick M, Zumwald A, Knöpfli B, et al. Challenging future, challenging past: the relationship of social integration and psychological impairment in traumatized refugees. Eur J Psychotraumatol 2016;7:28057. 10.3402/ejpt.v7.28057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakker L, Dagevos J, Engbersen G. The importance of resources and security in the socio-economic integration of refugees. A study on the impact of length of stay in asylum accommodation and residence status on socio-economic integration for the four largest refugee groups in the Netherlands. J Int Migr Integr 2014;15:431–48. 10.1007/s12134-013-0296-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beiser M. The health of immigrants and refugees in Canada. Can J Public Health 2005;96 Suppl 2:S30–44. 10.1007/BF03403701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Population characteristics Norway. ssb.no. Available: https://www.ssb.no/en/befolkning/nokkeltall/population [Accessed 2 Mar 2020].

- 12.Characteristics of persons with refugee background in Norway. ssb.no. Available: https://www.ssb.no/en/flyktninger [Accessed 2 Mar 2020].

- 13.UDI Want to apply. Available: https://www.udi.no/en/want-to-apply/ [Accessed 2 Mar 2020].

- 14.UNHCR. UNHCR Global Trends Global Trends - Forced Displacement in 2018, 2018. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2018/ [Accessed 26 Oct 2019].

- 15.Pew Research Center Where Syrian refugees have resettled worldwide. Available: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/29/where-displaced-syrians-have-resettled/ [Accessed 26 Oct 2019].

- 16.Johnson CM, Rostila M, Svensson AC, et al. The role of social capital in explaining mental health inequalities between immigrants and Swedish-born: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017;17:117. 10.1186/s12889-016-3955-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khawaja M, Tewtel-Salem M, Obeid M, et al. Civic engagement, gender and selfrated health in poor communities: Evidence from Jordan’s refugee camps. Health Sociology Rev 2006;15:192–208. 10.5172/hesr.2006.15.2.192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindström M, Hanson BS, Ostergren PO. Socioeconomic differences in leisure-time physical activity: the role of social participation and social capital in shaping health related behaviour. Soc Sci Med 2001;52:441–51. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00153-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ager A, Strang A. Understanding integration: a conceptual framework. J Refug Stud 2008;21:166–91. 10.1093/jrs/fen016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Castles S, Korac M, Vasta E, et al. Integration: mapping the field. Home Office Online Report 2002;29:115–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemi M, Manhica H, Gunnarsson D, et al. A scoping review and conceptual model of social participation and mental health among refugees and asylum seekers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:ijerph16204027. 10.3390/ijerph16204027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hynie M, Korn A, Tao D. Social context and social integration for Government Assisted Refugees in Ontario, Canada : Poteet M, Nourpanah S, After the flight: the dynamics of refugee settlement and integration. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars, 2016: 183–227. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thombs BD, Kwakkenbos L, Levis AW, et al. Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. CMAJ 2018;190:E44–9. 10.1503/cmaj.170691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffman YSG, Diamond GM, Lipsitz JD. The challenge of estimating PTSD prevalence in the context of ongoing trauma: the example of Israel during the second Intifada. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25:788–93. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036101supp001.pdf (37KB, pdf)