Abstract

Background

Many treatments are being assessed for repurposing to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). One drug that has shown promising results in vitro is nitazoxanide. Unlike other postulated drugs, nitazoxanide shows a high ratio of maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), after 1 day of 500 mg twice daily (BD), to the concentration required to inhibit 50% replication (EC50) of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Cmax : EC50 roughly equal to 14:1). As such, it is important to investigate the safety of nitazoxanide for further trials. Furthermore, treatments for COVID-19 should be cheap to promote global access, but prices of many drugs are far higher than the costs of production. We aimed to conduct a review of the safety of nitazoxanide for any prior indication and calculate its minimum costs of production.

Methods

A review of nitazoxanide clinical research was conducted using EMBASE and MEDLINE databases, supplemented by ClinicalTrials.gov. We searched for phase 2 or 3 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing nitazoxanide with placebo or active control for 5–14 days in participants experiencing acute infections of any kind. Data extracted were grade 1–4 and serious adverse events (AEs). Data were also extracted on gastrointestinal (GI) AEs, as well as hepatorenal and cardiovascular effects.

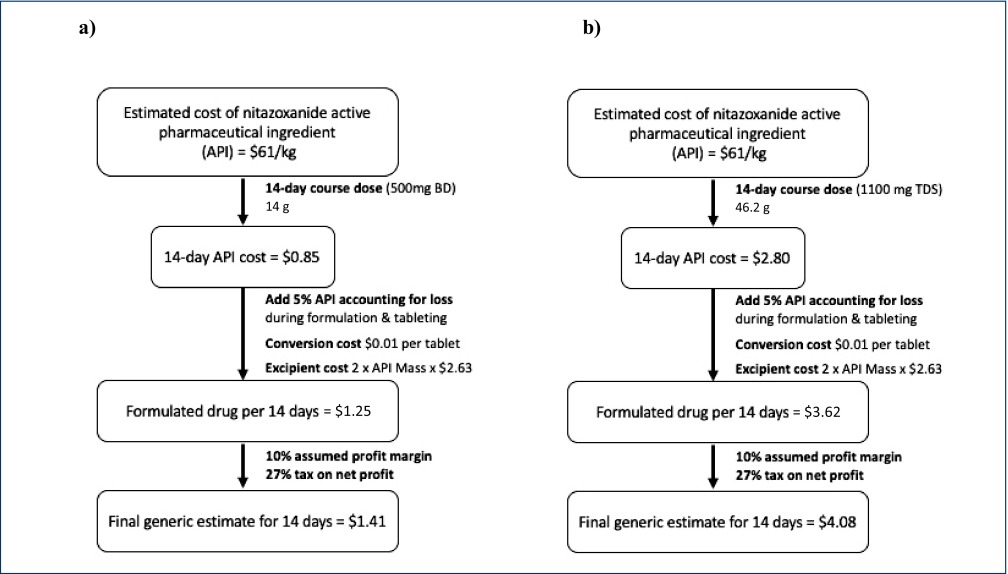

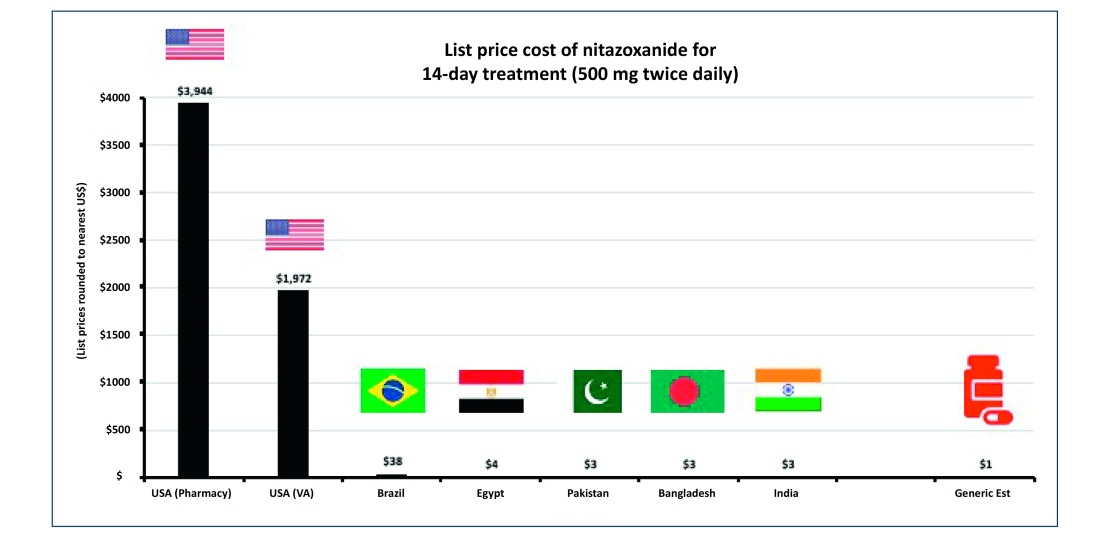

Active pharmaceutical ingredient cost data from 2016 to 2019 were extracted from the Panjiva database and adjusted for 5% loss during production, costs of excipients, formulation, a 10% profit margin and tax. Two dosages, at 500 mg BD and a higher dose of 1100 mg three times daily (TDS), were considered. Our estimated costs were compared with publicly available list prices from a selection of countries.

Results

Nine RCTs of nitazoxanide were identified for inclusion. These RCTs accounted for 1514 participants and an estimated 95.3 person-years-of-follow-up. No significant differences were found in any of the AE endpoints assessed, across all trials or on subgroup analyses of active- or placebo-controlled trials. Mild GI AEs increased with dose. No hepatorenal or cardiovascular concerns were raised, but few appropriate metrics were reported. There were no teratogenic concerns, but the evidence base was very limited.

Based on a weighted-mean cost of US $61/kg, a 14-day course of treatment with nitazoxanide 500 mg BD would cost $1.41. The daily cost would therefore be $0.10. The same 14-day course could cost $3944 in US commercial pharmacies, and $3 per course in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh. At a higher dose of 1100 mg TDS, our estimated cost was $4.08 per 14-day course, equivalent to $0.29 per day.

Conclusion

Nitazoxanide demonstrates a good safety profile at approved doses. However, further evidence is required regarding hepatorenal and cardiovascular effects, as well as teratogenicity. We estimate that it would be possible to manufacture nitazoxanide as generic for $1.41 for a 14-day treatment course at 500 mg BD, up to $4.08 at 1100 mg TDS. Further trials in COVID-19 patients should be initiated. If efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 is demonstrated in clinical studies, nitazoxanide may represent a safe and affordable treatment in the ongoing pandemic.

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a pandemic RNA virus belonging to the Betacoronaviridae genera, causing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In the wait for an effective vaccine, many therapeutics are being studied for potential repurposing to treat COVID-19. While candidate drugs have shown some activity against the virus, no specific treatment has yet been licenced apart from for compassionate use in severe cases [1]. Candidate drugs being explored in trials and for compassionate treatment include chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, darunavir, remdesivir, favipiravir, ivermectin, thiazolide antiprotozoal and nitazoxanide [2].

Nitazoxanide is a pro-drug for tizoxanide, which has broad-spectrum antiviral properties, has many viral indications and shows promising pharmacodynamics against Coronaviridae [3]. It has not yet been tested in COVID-19 patients but previously showed a low in vitro effective concentration (EC50) against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [4]. Nitazoxanide was therefore selected as a good candidate for potentially inhibiting SARS-CoV-2. To assess inhibition potential, researchers compared the maximum serum concentration of tizoxanide (Cmax) with the in vitro EC50 for nitazoxanide for SARS-CoV-2.

Single-dose plasma concentrations of tizoxanide have been reported to be dose proportional, but higher exposures were seen on administration of a single dose with food across 1000 mg, 2000 mg, 3000 mg and 4000 mg doses (at 1000 mg Cmax was 12,300 ng/mL fasted compared with 15,900 ng/mL with food) [5]. The pharmacokinetics of tizoxanide have also been assessed over 7 days following administration orally at 500 mg and 1000 mg BD with food [6]. Pharmacokinetics were not influenced by repeat dosing at 500 mg BD (Cmax 10,400 ng/mL after single dose compared with 12,200 ng/mL on day 7) but increased considerably after repeat dosing at 1000 mg BD (Cmax 16,800 ng/mL after single dose vs 26,400 ng/mL on day 7) [6]. All reported Cmax values for tizoxanide exceeded the reported in vitro EC50 of nitazoxanide for SARS-CoV-2 [651 ng/mL (2.12 μM)] [7]. Nitazoxanide concentration has also been specifically predicted to exceed its EC50 for SARS-CoV-2 by 3.1-fold in the lung [8]. It should be noted that this EC50 value was reported for nitazoxanide rather than its human metabolite, tizoxanide, but previous studies have shown similar activity to nitazoxanide when tested against various strains of influenza [9].

Care needs to be taken with in vitro potency assessments and their applicability. Generally, a high Cmax to EC50 ratio in vitro means a higher potential for in vivo viral inhibition. However, these values are not standardised and can be affected by many variables [10]. It is important also to consider the mechanism of action of nitazoxanide and to carry out clinical trials assessing in vivo inhibition of SARS-CoV-2.

A reduced innate immune response is hypothesised to explain age-susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 [11]. Nitazoxanide upregulates the host interferon pathway, amplifying the innate antiviral response [12]. Nitazoxanide could therefore be a useful adjunctive treatment used earlier in the disease course than more potent virus-targeted treatments (hydroxychloroquine EC50 = 1.13 μM, remdesivir EC50 = 0.77 μM) [7].

Previous indications of nitazoxanide vary widely. It is licenced by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for giardiasis [13]. However, it has been trialled and used for many other diseases, including cryptosporidiosis diarrhoea in HIV patients, influenza, hepatitis viruses, rotavirus and norovirus. As such, the safety profile of nitazoxanide is variably reported and needs clarification before potential large-scale trial and treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, COVID-19 treatment courses are given for 7–14 days; therefore, whether nitazoxanide is safe to use needs to be proven for this duration [14].

Novel COVID-19 treatments must not only be safe and effective but also cheap and readily available. Many potential candidate drugs currently being investigated have been shown to be producible as generic medicines at very low costs per course of treatment, including some that can be manufactured for under US$1 per day [14]. These estimated generic prices can be calculated based on estimated dosage and costs of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API), accounting for a reasonable profit margin and tax. This approach has been used previously to estimate reliably the costs of production for hepatitis C and HIV drugs among others [15–17]. However, prices of drugs to treat coronavirus can be far higher than costs of production, impacting access [14].

We aimed to review the existing evidence on the safety of nitazoxanide and calculate its potential minimum costs of production to inform its potential use for the treatment of COVID-19.

Methods

Safety review

A review of nitazoxanide clinical research was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane framework for systematic reviews, following the PRISMA statement reporting method for systematic reviews and meta-analyses [18]. A search was conducted using EMBASE and MEDLINE databases via Ovid (full search terms available upon request) and supplemented by a further search of ClinicalTrials.gov for all studies listed with nitazoxanide as an intervention. The search was concluded on 6 April 2020.

We searched for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing nitazoxanide with placebo or an active control in participants experiencing acute infections of any kind. Trials were required to be phase 2 or 3 studies carried out in either adult or paediatric trial populations. Participants were required to undergo at least 5 days of nitazoxanide. Trials with shorter courses of treatment were excluded, as briefer exposure to the drug might positively skew results and would be less comparable with potential treatment use in COVID-19. Trials assessing the use of nitazoxanide in participants with severe chronic disease were excluded, as these could present different adverse event (AE) profiles and drug interactions. Studies were screened against these criteria independently by two reviewers, and mutual agreement was necessary for inclusion or exclusion where conflicts arose.

Further analysis was undertaken of all available safety data. Data extracted were AEs grade 1–4 and serious AEs. Data were also extracted on gastrointestinal (GI) AEs, as well as hepatorenal and cardiac effects, as specific AEs of interest identified from phase 1 studies and drug licencing reports [19,20]. Hepatic, renal and cardiovascular endpoints were studied because of the deleterious effects of COVID-19 on these systems [21,22]. Any appropriate metrics reported for these systems in the included papers were extracted. Further, dose ranging studies from the same search were isolated for investigation of safety at higher doses, as may be needed for COVID-19.

We searched for data in published articles, supplementary appendices and at ClinicalTrials.gov. Where there were inconsistencies, data reported in the published paper were preferred. To standardise the extracted data, the number of participants experiencing AEs was extracted for grade 1–4 AE. For GI AE and serious AE, number of events was preferred as this was more consistently reported and better represented the event occurrence rates, as one person could experience multiple events and event types. All reported AE data were extracted, rather than only those deemed related to the study drug, to avoid reporting bias as much a possible. Instead, comparison control arms were used to determine the effects of the study drug. Statistical comparisons of event proportions were also carried out using z-tests.

Costs analysis

We followed methodology used recently to estimate the minimum costs of production for other potential treatments of COVID-19 currently undergoing clinical trials by Hill et al. to calculate the potential cost of nitazoxanide treatment based on the cost of API [14]. API cost data were extracted from the Panjiva database of global shipping records between 2016 and 2019, and adjusted for 5% loss during production, costs of excipients (other components within the finished medication such as stabilisers and bulking agents), formulation, a 10% profit margin and tax [23]. Because treatment duration varies between protocols, we assumed a conservative 14-day duration in this study. Two dosages, at 500 mg BD and at a higher dose of 1100 mg three times daily (TDS), were considered to account for potential COVID-19 dose optimisation including the potential need for higher doses if given without food.

Our estimated costs were compared with publicly available list prices from a selection of countries, with prices converted to US dollars based on the average 12-month exchange rate in 2019. One data source was used per country, and where multiple prices were listed, the cheapest was selected [24–30].

Results

Review of safety

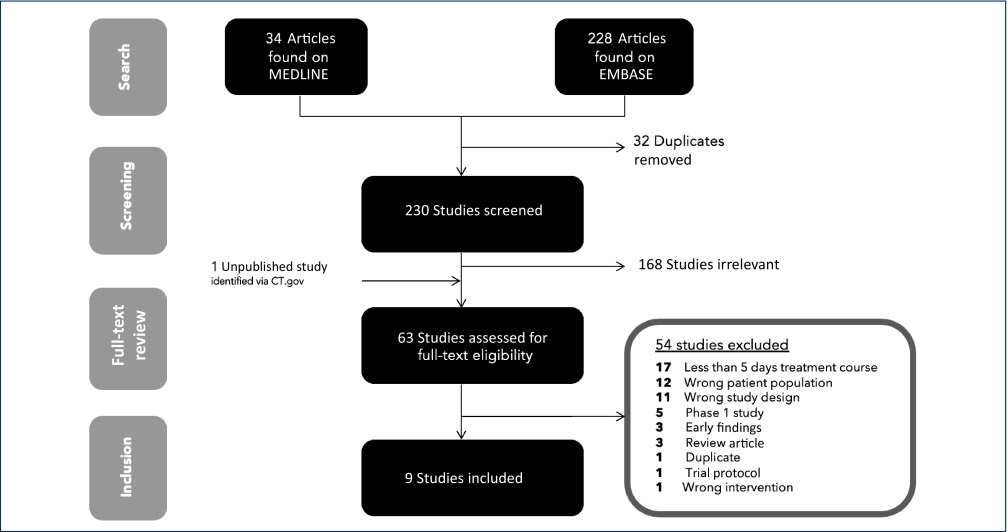

After screening against the prespecified criteria, nine RCTs of nitazoxanide for previous indications were identified for inclusion (Figure 1). Seventeen trials were excluded given their short (commonly 3-day) courses of nitazoxanide treatment. Twelve trials were excluded as they assessed nitazoxanide in patients who had severe chronic illnesses such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cancers, late-stage liver disease or hepatitis C virus infection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart detailing the search and screening results

The nine included trials accounted for 1514 participants for an estimated 95.3 person-years-of-follow-up [31–39]. Of these patients, 925 were on nitazoxanide. One trial reported results in separate paediatric and adult populations [38]. In total, only 50/1514 (3.3%) participants were paediatric. Studies were carried out in a wide range of countries worldwide: USA, Egypt, Peru, Mexico and Haiti. The most common dosing of nitazoxanide was 500 mg BD, but some studies used 1000 mg BD. Paediatric doses varied and were determined by weight or age. On pooling available study demographics, 45.6% of participants were female, and the mean age of participants was 37 years.

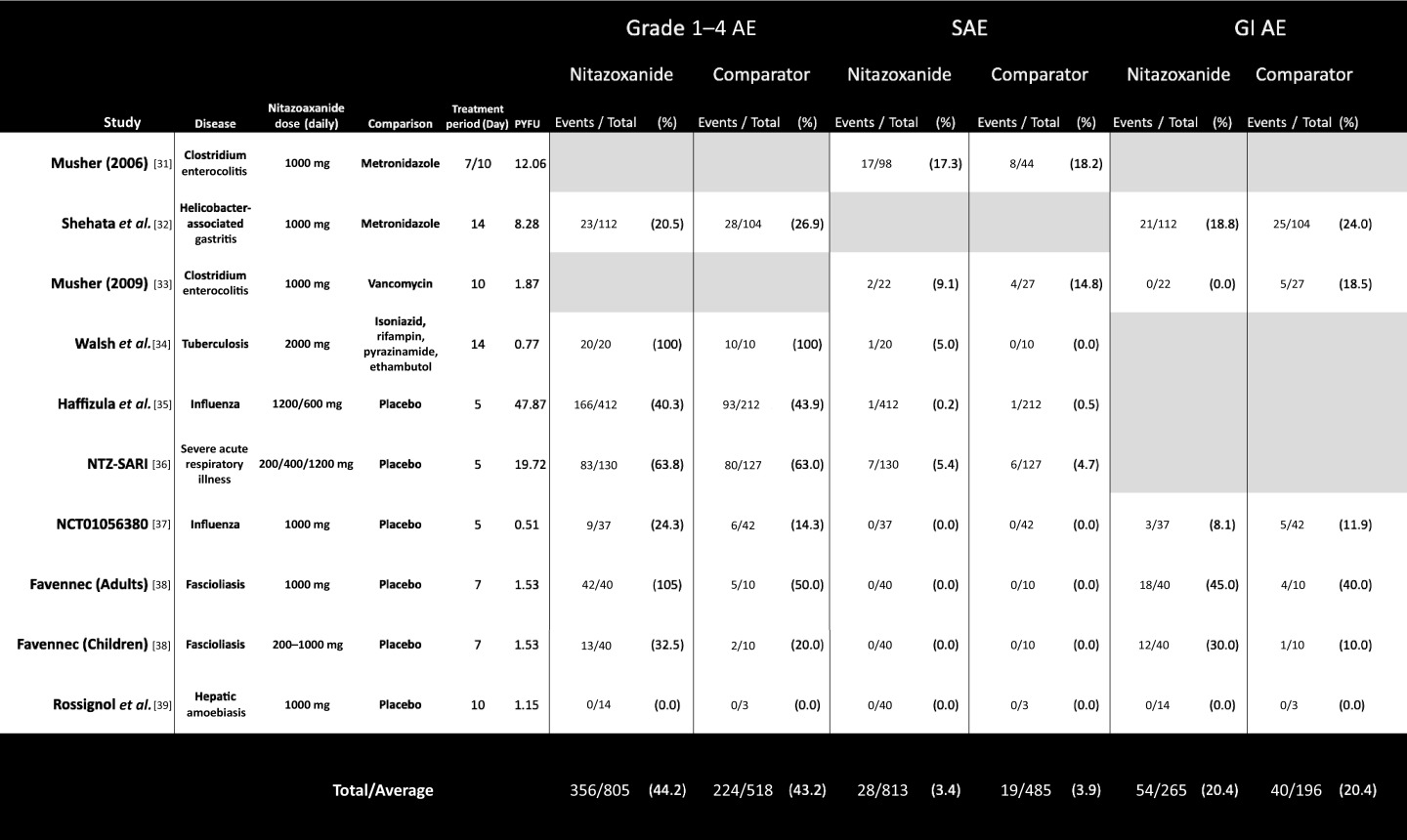

Five studies used placebo comparison (n = 1077) and four used antibiotic comparators including metronidazole (n = 437), vancomycin and standard tuberculosis therapy (Table 1). Study populations had a variety of pathologies, including Clostridium difficile, Helicobacter pylori, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, viral influenza and amoebiasis.

Table 1.

Summary of safety data extracted from the six phase 2 and 3 controlled studies with adverse event reporting. Extracted data for six reported safety endpoints shown for each included study

|

AE: adverse events; SAE: serious adverse events; GI: gastrointestinal.

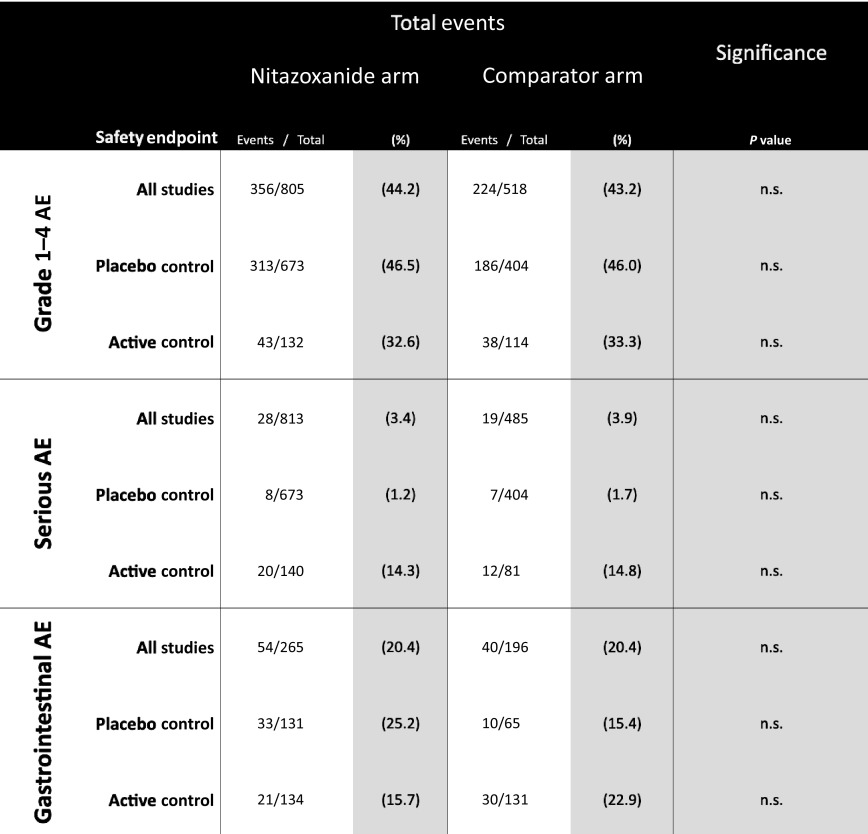

Table 2 shows the overall event numbers and percentage proportions for each of the three AE endpoints, as well as the comparative significance of differences between nitazoxanide and comparator arms. These results are further stratified by comparator type into results from studies using a placebo control and studies using active antimicrobial control regimens. The results from those trials that used placebo comparison isolate the specific effects of nitazoxanide.

Table 2.

Incidence of adverse events in randomised trials of nitazoxanide

|

AE: adverse events.

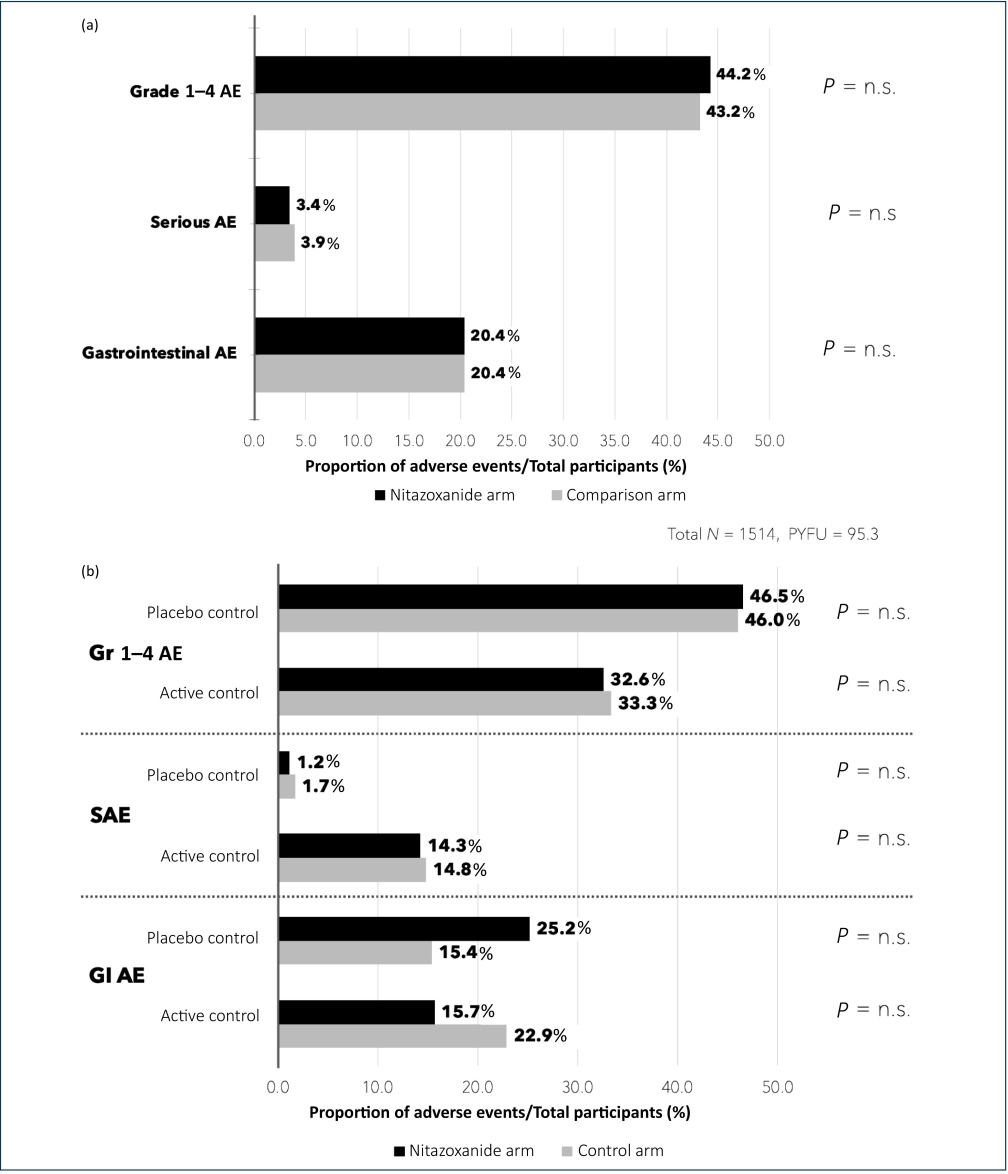

There was no significant difference in AE proportions for any of the endpoints assessed, across all trials or on subgroup analysis of active-controlled and placebo-controlled trials. The largest difference in event proportions was seen in GI AEs occurring in placebo-controlled trials, with 33/131 participants (25.2%) on nitazoxanide vs 10/65 participants (15.4%) on placebo, but this was also not statistically significant (Table 2). Figure 2a illustrates the event proportions occurring across all trials and Figure2b, the event proportions on subgroup analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Event proportions occurring across reported safety endpoints in all nine included studies (both placebo controlled and active controlled). (b) Event proportions occurring across reported safety endpoints, stratified into results from studies using a placebo controlled and studies using active antimicrobial control.

AE: adverse events; P = n.s: P-value non-significant; SAE: serious adverse events; Gr: grade; GI: gastrointestinal; PYFU: person-years-of-follow-up

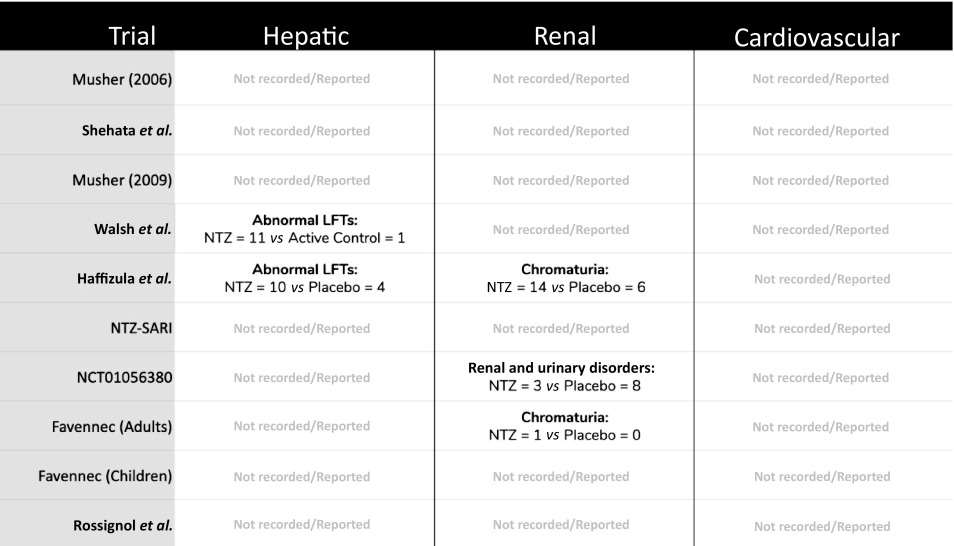

Hepatorenal and cardiovascular endpoints

Safety data reported in all nine included studies showed specific hepatic, renal and cardiovascular AEs were either not widely assessed (via biomarkers or symptom reporting) or not widely reported. Some studies had a threshold of 1%–5% incidence rate before an adverse event type would be reported, which would explain why these adverse events are not consistently reported. As a marker of hepatic effect, two studies reported elevations in liver function tests in participants receiving nitazoxanide compared with control (Table 3). As a marker of potential renal effect, two studies reported higher rates of chromaturia (yellow urine) in participants taking nitazoxanide, but all of these cases were mild and clinically insignificant (Table 3). No cardiovascular AEs were recorded or reported in any of the nine studies (Table 3).

Table 3.

Safety data related to hepatic, renal or cardiovascular adverse effects of nitazoxanide, where reported across the nine included studies

|

LFTs: liver function tests; NTZ: nitazoxanide; Hepatic: LFT or other relevant biochemical abnormality; Renal: any urinary or renal-related biochemical abnormality (creatinine, urea, electrolytes etc); Cardiovascular: (B-type natriuretic peptide, troponin, chest pain, QT prolongation, cardiac events etc).

WHO VigiAccess, which contained records of 472 AEs for nitazoxanide, showed very few reported cases of hepatotoxicity (n = 3), jaundice (n = 5) and other hepatobiliary disorders (n = 10) [40]. More AEs were reported as renal and urinary disorders, but the vast majority were cases of chromaturia (n = 63). Of note were nine cases of dysuria and four cases of azotaemia [40]. No thrombotic disorders were noted on VigiAccess, but there were nine cases of dysrhythmia and three cases of acute coronary syndrome [40].

Dose-dependent adverse events

On review of the available literature, no concerns were raised regarding dose-dependent AEs. However, in one study which used single doses at 1000 mg up to 4000 mg, mild GI AEs escalated with dose [5]. On investigation of QT interval, no prolongation was observed with increased dose [41].

Costs analysis

Regarding minimum costs of production, our analysis show that based on a weighted-mean API cost of $61/kg, and a daily dose of 1000 mg (500 mg BD), a 14-day course of treatment with nitazoxanide would cost $1.41 after accounting for loss, excipients, formulation, profit and tax (Figure 3a). The daily cost would therefore be $0.10. In comparison, the same 14-day course could cost $3944 in US commercial pharmacies, and only $3 per course in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, as shown in Figure 4. At a higher dose of 1100 mg TDS, our estimated cost increased to $4.08 per 14-day course (Figure 3b), equivalent to $0.29 per day.

Figure 3.

Algorithm for cost estimation of 14-day course of generic nitazoxanide. (a) Estimated cost of production for dosing at 500 mg BD. (b) Estimated cost of production for dosing at 1100 mg TDS.

API: active pharmaceutical ingredients; BD: twice daily; TDS: three times daily.

Figure 4.

List prices of 14-day course of nitazoxanide in selected countries.

API: active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Discussion

This analysis reviews clinical data on the safety of nitazoxanide and summarises available data from nine relevant RCTs, accounting for 1514 participants and an estimated 95.3 person-years-of-follow-up. Nitazoxanide demonstrates overall favourable safety, with no significant difference in the occurrence of total AEs, serious or GI AEs compared with other antimicrobial regimens or with placebo control.

Regarding minimum costs of production, our analysis found that based on a daily dose of 1000 mg (500 mg BD), a 14-day course of treatment with nitazoxanide would cost $1.41. Therefore, if efficacy against COVID-19 is demonstrated in clinical studies, nitazoxanide may represent safe and affordable treatment in the ongoing pandemic.

Limitations

Our analysis is limited to the publicly available body of literature. In the nine studies eligible for inclusion, treatment duration ranged 5–14 days, so the findings of this review can be applied only to similarly short courses of nitazoxanide and longer-term safety cannot be commented on. Although this is similar to the likely duration of COVID-19 treatment, any potential usage in prevention would require further evidence to assess cumulative toxicity effect.

Although in vitro findings suggest that nitazoxanide might be active against COVID-19, it is not yet clear at what doses it needs to be administered to achieve clinical effect. It is likely that higher doses are needed. The studies included in this review most commonly used doses of 500 mg BD, with age and weight variability in paediatric dosing. Dose ranging studies were small and of shorter duration. If doses of >1000 mg per day are required for COVID-19 treatment, the possibility of dose-dependent AE should be considered and further review will be required.

The generalisability of these findings is limited to the settings and populations in which the included trials were carried out, with a large proportion of the participants from the included studies being young (mean age 37 years). This means findings may be less applicable to older COVID-19 patients.

Gastrointestinal effects

Phase 1 studies of nitazoxanide identified GI events as the most common side effect. These events were mild and no other serious events were noted [6,20]. On literature review, many small studies for 3 days of nitazoxanide to treat diarrhoeal disease in paediatric populations reported increased rates of mild, transient GI AEs on nitazoxanide, such as abdominal pain, but few severe or persistent AEs.

Gastrointestinal AEs were difficult to distinguish from GI events caused by the acute infections nitazoxanide was being employed to treat in these studies; therefore placebo comparison is vital. This review finds a higher proportion of GI AEs on nitazoxanide compared with control, particularly in placebo-controlled trials. However, the difference was not statistically significant. In all included studies, GI events were generally mild and most commonly included abdominal pain and diarrhoea.

Cardiovascular effects

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the cardiovascular effect of COVID-19. Relatively common complications include myocarditis, with changes on ECG and echocardiogram. Increases in troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide may be prognostic [42–44]. There is also a procoagulatory effect of moderate to severe COVID-19 [45], with prothrombotic states leading to embolic events [46,47] and D-dimer being shown to act as a prognostic indicator [48,49].

Given the known cardiovascular complications of COVID-19, it is important to assess the cardiovascular effects of potential treatments. A phase 1 study of nitazoxanide showed no QT prolongation in healthy volunteers [41]. However, there has been no specific further study in later stage clinical trials. None of the nine studies included in this review reported any cardiovascular AEs, although it is possible that studies did not monitor for relevant biomarkers and any cardiac effect may have been overlooked.

Hepatorenal effects

Prescribing information from the FDA lists nitazoxanide safety as unstudied in patients with hepatic and renal impairment [19]. COVID-19 is known to cause liver damage, renal failure and dehydration [21,22]. In particular, COVID-19 patients are prone to hepatic transaminitis, proteinuria and increased serum creatinine and uric acid [21,22]. In the nitazoxanide studies reviewed, none of these markers were reported except for deranged liver function tests in two. As such, we call for reporting of hepatorenal endpoints in future studies of nitazoxanide, especially those undertaken in COVID-19 patients.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Regarding the potential for teratogenic effects of nitazoxanide, the existent evidence base is limited. In early animal studies, nitazoxanide did not adversely affect fertility, even at high doses in rats. There was also no evidence of harm to the fetus in rats or rabbits, despite high-dose regimens. However, there are no adequate studies assessing the effects of nitazoxanide in pregnant women, and it is not known whether nitazoxanide is excreted in human breast milk [20]. Therefore, the FDA catagorises the potential of teratogenic effects as ‘Category B’ [19], denoting no particular cause for concern but an inadequate evidence base to draw a complete conclusion on safety. Caution continues to be advised in both pregnant women and nursing mothers.

Dose-dependent effects

Much higher doses than used in studies included in this review may be indicated for in vivo inhibition of SARS-CoV-2. Although no serious dose-dependent AEs have been noted in the literature for nitazoxanide, there are limited data on the use of nitazoxanide at higher doses. At a higher dose, nitazoxanide has been shown to cause mild GI AEs, but not to prolongate QT interval.

Costs of production

As expected, our estimated cost of production, both for a 14-day period and on a daily basis, is very low and in line with potential COVID-19 treatments already analysed [14]. Therefore, should future clinical trial data support the use of nitazoxanide therapy for COVID-19, it could be mass produced at a minimal cost to ensure wide access especially for low- and middle-income countries.

It is worth noting, however, that our estimated costs presume that production is carried out by a generic manufacturer, for example in India (which is the leading centre of generic drug manufacturing), where associated costs of capital investment, overhead and labour are significantly less than originator companies, in this case Romark Laboratories. Additionally, when comparing against current list prices, the ‘real’ list price in countries may be lower because of in-country negotiated discounts.

Conclusion

Nitazoxanide demonstrates an overall favourable safety profile, with no significant difference in the occurrence of total AEs, serious or gastrointestinal AEs compared with other antimicrobial regimens or with placebo control. Further evidence is required regarding specific hepatorenal and cardiovascular effects, as well as the potential for teratogenicity, but existing evidence provides no particular cause for concern. However, we recommend caution and careful monitoring in hepatorenally impaired patients.

We estimate that it would be possible to manufacture nitazoxanide as generic for $1.41 for a 14-day treatment course at 500 mg BD, up to $4.08 at 1100 mg TDS. A Mexican study comparing nitazoxanide with hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19 is currently recruiting (US Clinical Trials registry number NCT04341493) participants. Further trials in COVID-19 patients should be initiated, but the high reported in vitro activity of nitazoxanide against SARS-CoV-2 should also be confirmed. If efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 is demonstrated in clinical studies, nitazoxanide may represent a safe and affordable treatment in the ongoing pandemic.

Funding

Funding received from the International Treatment Preparedness Coalition as part of the Unitaid-supported project ‘Affordable Medicines for Developing Countries’.

Conflicts of interest

VP and TP have no conflicts of interest to declare. AH received a consultancy payment from Merck for a clinical trial review that is not connected with this project. AO received grant funding and consultancy from Merck, ViiV Healthcare and Gilead. He is a Director for Tandem Nano Ltd, which is not related to this project.

References

- 1. US Food and Drug Agency Fact sheet for health care providers emergency use authorization (EUA) of hydroxychloroquine sulfate supplied from the strategic national stockpile for treatment of COVID-19 in certain hospitalized patients ( 2020). Available at: www.fda.gov/media/136537/download ( accessed April 2020).

- 2. Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ et al. . Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA 2020; 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Padmanabhan S. Potential dual therapeutic approach against SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 with nitazoxanide and hydroxychloroquine ( 2020). 10.13140/RG.2.2.28124.74882. Available at: www.researchgate.net/publication/339941717 ( accessed April 2020). [DOI]

- 4. Rossignol JF. Nitazoxanide, a new drug candidate for the treatment of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Public Health 2016; 9( 3): 227– 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stockis A, Allemon AM, De Bruyn S et al. . Nitazoxanide pharmacokinetics and tolerability in man using single ascending oral doses. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 40( 5): 213– 220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stockis A, De Bruyn S, Gengler C et al. . Nitazoxanide pharmacokinetics and tolerability in man during 7 days dosing with 0.5 g and 1 g b.i.d. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2002; 40( 5): 221– 227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L et al. . Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020; 30( 3): 269– 271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arshad U, Pertinez H, Box H et al. . Prioritisation of potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug repurposing opportunities based on ability to achieve adequate target site concentrations derived from their established human pharmacokinetics. medRxiv 22 April 2020 Available at: www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.16.20068379v1 ( accessed April 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossignol JF, La Frazia S, Chiappa L et al. . Thiazolides, a new class of anti-influenza molecules targeting viral hemagglutinin at the post-translational level. J Biol Chem 2009; 284( 43): 29798– 29808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Montaner J, Hill A, Acosta E. Practical implications for the interpretation of minimum plasma concentration/inhibitory concentration ratios. Lancet 2001; 357( 9266): 1438– 1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Song YG, Shin H-S. COVID-19, a clinical syndrome manifesting as hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Infect Chemother 2020; 52( 1): 110– 112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jasenosky LD, Cadena C, Mire CE et al. . The FDA-approved oral drug nitazoxanide amplifies host antiviral responses and inhibits Ebola virus. iScience 2019; 19: 1279– 1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. FDA Approval of nitazoxanide. Department of Health and Human Services ( 2004). Available at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2004/21-497_Alinia_Approv.pdf ( accessed April 2020).

- 14. Hill A, Wang J, Levi J et al. . Minimum costs to manufacture new treatments for COVID-19. J Virus Erad 2020; 6( 2): 61– 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hill A, Simmons B, Gotham D et al. . Rapid reductions in prices for generic sofosbuvir and daclatasvir to treat hepatitis C. J Virus Erad 2016; 2( 1): 28– 31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hill AM, Barber MJ, Gotham D. Estimated costs of production and potential prices for the WHO essential medicines list. BMJ Glob Health 2018; 3( 1): e000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hill A, Khoo S, Fortunak J et al. . Minimum costs for producing hepatitis C direct-acting antivirals for use in large-scale treatment access programs in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58( 7): 928– 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6( 7): e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alinia ® (nitazoxanide) tablets (nitazoxanide) for oral suspension. Available at: www.alinia.com/healthcare-professionals/alinia-nitazoxanide-500-mg-tablets/ ( accessed April 2020).

- 20. Prescribing information; Alina®. FDA, 2005. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/021818lbl.pdf ( accessed April 2020).

- 21. Ong J, Young BE, Ong S. COVID-19 in gastroenterology: a clinical perspective. Gut 2020; 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang X, Sun R, Chen D. Diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19: acute kidney injury cannot be ignored. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2020; 100: Available at: rs.yiigle.com/yufabiao/1184356.htm [ Article in Chinese]. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Panjiva Global trade insights. Available at: www.panjiva.com ( accessed April 2020).

- 24. Drugs.com Drug price information. Available at: www.drugs.com/price-guide/.

- 25. US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Procurement, Acquisitions and Logistics. Pharmaceutical Prices 15 March 2020. Available at: www.va.gov/opal/nac/fss/pharmPrices.asp ( accessed April 2020).

- 26. Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency Drug price lists. Available at: portal.anvisa.gov.br/listas-de-precos ( accessed April 2020).

- 27. MedIndia Drug price of all the brand names. Available at: www.medindia.net/drug-price/index.asp ( accessed April 2020).

- 28. MedEx A comprehensive online medicine index of Bangladesh. Available at: www.medindia.net/drug-price/index.asp ( accessed April 2020).

- 29. Sehat Pharmacy. Available at: sehat.com.pk/ ( accessed April 2020).

- 30. Egyptian Drug Store. Available at: egyptiandrugstore.com/index.php?route=common/home ( accessed April 2020).

- 31. Musher DM, Logan N, Hamill RJ et al. . Nitazoxanide for the treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 43( 4): 421– 427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shehata MA, Talaat R, Soliman S et al. . Randomized controlled study of a novel triple nitazoxanide (NTZ)-containing therapeutic regimen versus the traditional regimen for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter 2017; 22( 5): e12395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Musher DM, Logan N, Bressler AM et al. . Nitazoxanide versus vancomycin in clostridium difficile infection: a randomized, double-blind study. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 48( 4): e41– e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walsh KF, Mcaulay K, Lee MH et al. . Early bactericidal activity trial of nitazoxanide for pulmonary. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64( 5): e01956– 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haffizulla J, Hartman A, Hoppers M et al. . Effect of nitazoxanide in adults and adolescents with acute uncomplicated influenza: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b/3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14( 7): 609– 618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gamiño-Arroyo A, Luerrero L, McCarthy S et al. . Efficacy and safety of nitazoxanide in addition to standard of care for the treatment of severe acute respiratory illness. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69( 11): 1903– 1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. ClinicalTrials.gov Study of nitazoxanide in adults with acute uncomplicated influenza. Identifier: NCT01056380 Bethesda (MD): US National Library of Medicine. 2010 January 26 Available at: clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01056380 ( accessed April 2020).

- 38. Favennec L, Jave Ortiz J, Gargala G et al. . Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of nitazoxanide in the treatment of fascioliasis in adults and children from northern Peru. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 17( 2): 265– 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rossignol JF, Kabil SM, El-Gohary Y et al. . Nitazoxanide in the treatment of amoebiasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2007; 101( 10): 1025– 1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. VigiAccess. Available at: www.vigiaccess.org/ ( accessed April 2020).

- 41. Täubel J, Lorch U, Rossignol J-F et al. . Analyzing the relationship of QT interval and exposure to nitazoxanide, a prospective candidate for influenza antiviral therapy – a formal TQT study. J Clin Pharmacol 2014; 54( 9): 987– 994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J et al. . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and cardiovascular disease circulation. Circulation 2020; 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng YY, Ma YT, Zhang JY et al. . COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020; 17( 5): 259– 260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W et al. . Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med 2020; 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al. . Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395( 10229): 1054– 1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cui S, Chen S, Li X et al. . Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost 2020; 10.111/jth.14830. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Danzi G, Loffi M, Galeazzi G. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J 2020; 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gao Y, Li T, Han M et al. . Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J Med Virol 2020; 10.1002/jmv.25770. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lippi G, Favaloro EJ. D-dimer is associated with severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a pooled analysis. Thromb Haemost 2020; 10.1055/s-0040-1709650. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]