Abstract

Coagulation abnormalities and thrombosis have been recently identified as sequelae of severe infection with the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). We report a case of severe coagulopathy manifesting with right upper limb arterial and deep vein thrombosis in an 80-year-old male patient with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. He clinically deteriorated and received care in the intensive care unit where he was intubated. At that point, his coagulation laboratory tests were deranged, and he eventually developed dry gangrene in his right thumb and index finger, as well as a deep venous thromboembolism in his right axillary vein. Despite receiving treatment dose anticoagulation and undergoing arterial embolectomy, revascularization was unsuccessful. Amputation of the right arm at the level of the elbow was considered, but the patient died from respiratory failure.

Keywords: coagulopathy, arterial thrombosis, deep vein thrombosis, novel coronavirus pneumonia, revascularization

INTRODUCTION

Since the beginning of the pandemic, it has become evident that COVID-19 infection does not only affect the respiratory tract but in some patients it seems to evolve to a systemic disease with severe complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multi-organ failure [1]. Approximately 20–55% of patients with COVID-19 infection develop coagulation abnormalities, which correlate with the severity of their infection and are associated with higher mortality [2]. Patients with COVID-19 coagulopathy have a tendency to develop both arterial and venous thromboembolic events than bleeding [3]. There is little knowledge so far as to the optimal management of these patients, as COVID-19-related coagulopathy appears to have distinct clinicopathological features from other systemic coagulopathies associated with severe infection such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [4].

We present a case of an 80-year-old patient with confirmed COVID-19 infection, who developed severe coagulopathy with peripheral arterial infarcts and deep venous thromboembolism. He was admitted to G. Papanikolaou General Hospital in Thessaloniki, a tertiary hospital set as a reference center for COVID-19 patients.

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old man presented to the emergency department with fever, shortness of breath and a dry cough. His past medical history included hypertension, well-controlled non-insulin-dependent diabetes and mild dementia. His regular medications were amlodipine 10 mg once a day and metformin 1000 mg twice daily, and he was not known to have any drug allergies. He was a non-smoker and consumed alcohol socially. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and according to the guidelines issued by the Greek National Public Health Organization, the patient was admitted under the respiratory medicine department, was isolated as a potential COVID-19 positive case and underwent a nasopharyngeal swab. The diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was confirmed with a reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay.

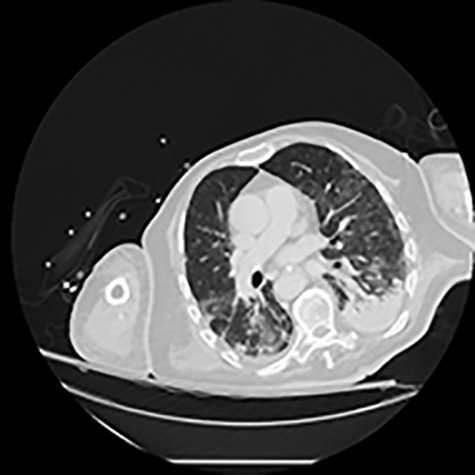

He initially received supportive treatment but clinically deteriorated 48 h post admission, developing hypoxemic respiratory failure. His chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) of the chest at that time revealed multiple ground glass opacities and areas of consolidation (Fig. 1). He was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), where he was intubated, and his treatment was escalated to broad-spectrum antibiotics and hydroxychloroquine. He had been on prophylactic enoxaparin (6000 IU/once daily) since the beginning of his hospital admission. Laboratory results upon ICU transfer are summarized in Table 1. In regard to his coagulation parameters, he had a prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), increased D-dimer and fibrinogen. His platelets were within normal range.

Figure 1.

CT of the chest showing bilateral multiple ground glass opacities and areas of consolidation consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and laboratory findings

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Age: year | 80 |

| Sex | Male |

| Medical history | Non-insulin-dependent diabetes, dementia |

| Laboratory findings on ICU admission | |

| White cell count (per mm3) | 5600 |

| Differential count (per mm3) | |

| Neutrophils | 4900 |

| Lymphocytes | 600 |

| Monocytes | 100 |

| Platelet count (per mm3) | 174 000 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 123 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 42 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 43 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 534 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 27 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 134 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 15.4 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (s) | 27.8 |

| International normalized ratio | 1:31 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 3.6 |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 13.6 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 166 |

| Ferritin (μg/L) | 721 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) | 0.1 |

| Cardiac troponin I (pg/ml) | 342 |

Seven days later, while his general condition was deteriorating, he developed acute ischemia in his right thumb and index finger (Fig. 2). In the ipsilateral forearm, a radial artery catheter had been inserted for monitoring. An urgent radial artery embolectomy was performed and restored the arterial supply to the right hand. The antithrombotic agent was changed to fondaparinux (7.5 mg/once daily). However, within the next few days, it was clinically evident that the revascularization effort was unsuccessful as the thumb and index finger developed dry gangrene. On examination, there was no palpable radial pulse, the ulnar artery pulse was palpable at the level of the wrist and the capillary refill time was normal at the middle, ring and little fingers. A CT angiography (Figs 3 and 4) was performed, demonstrating complete thrombosis of the radial artery beginning at the level of the elbow as well as a 70% occlusion of the ulnar artery ~15 cm proximal to the wrist. Thrombosis of the right axillary vein was also seen (Fig. 5). Orthopedic review was requested for consideration for finger amputation with a recommendation for arm amputation at the level of the elbow. Unfortunately, the patient died 72 h later from respiratory failure following a 24-day admission in ICU.

Figure 2.

Dry gangrene of the right thumb and index fingers.

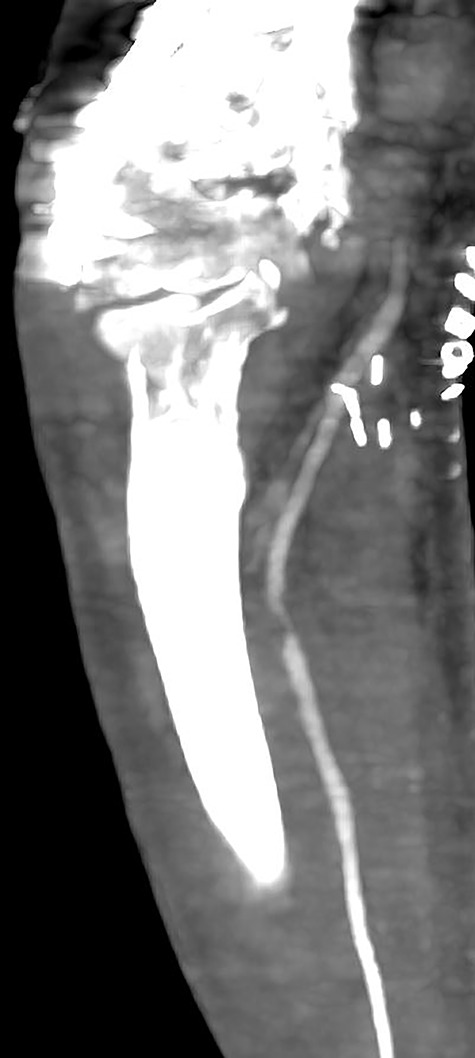

Figure 3.

CT angiography of the right upper limb with volume rendering showing complete radial artery thrombosis beginning at the level of the elbow at the same level that embolectomy was performed. Also, there was significant ulnar artery stenosis near occlusion, ~15 cm proximal to the wrist. The ulnar artery appeared to be normal peripherally to the level of obstruction, with no collaterals being visible.

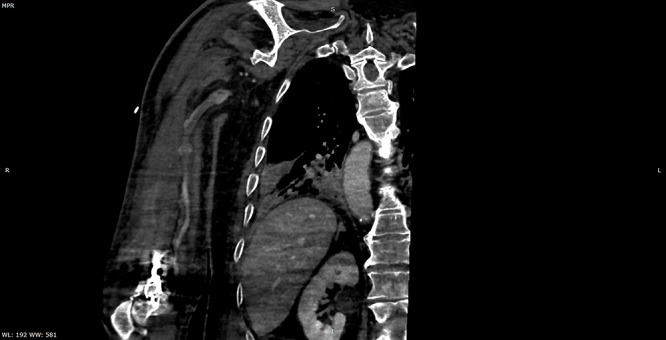

Figure 4.

Multiplanar reformation image shows severe near occlusion 6-mm stenosis of the ulnar artery.

Figure 5.

Multiplanar reformation image shows filling defect in the right axillary vein consistent with thrombosis.

DISCUSSION

There is a growing amount of evidence associating severe COVID-19 infection with a hypercoagulable state with distinct characteristics from that of other infection-associated coagulopathies [2, 4]. This has been reported to manifest with peripheral arterial infarcts as well as with pulmonary and deep venous thromboembolisms in critically ill patients, even despite anticoagulation [3, 5].

Marked elevation of D-dimers and fibrinogen along with some degree of thrombin (PT) and aPTT prolongation have been frequently reported hemostatic abnormalities in patients with COVID-19 and associated with worse survival outcomes.[6] In some cases, the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies has also been reported [5, 7].

The exact pathogenetic mechanisms underpinning this hypercoagulable state are yet to be fully elucidated. It remains unclear whether endothelial injury is caused directly by COVID-19 or as consequence of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome or even triggered by the use of intravascular catheters [8]. Results from autopsy studies in patients who died from COVID-19 infection revealed the presence of generalized thrombotic microangiopathy mainly affecting elderly male individuals with obesity and cardiovascular comorbidities.[9] However, arterial events presenting as acute limb ischemia have also been reported in younger patients with no comorbidities and while receiving prophylactic dose low molecular weight heparin [10]. It remains unclear from the existing literature whether amputation has any merit in the management of acute limb ischemia when mechanical and pharmacological attempts for revascularization have failed.

Effective prevention and treatment measures for these thromboembolic events remain a challenge due to the lack of a clear understanding of the exact underlying mechanism, as well as the paucity of high-quality studies. Our case contributes further evidence to the existing literature regarding the systemic thromboembolic complications associated with COVID-19 and highlights their adverse prognostic impact. It is critical to monitor for thromboembolic events particularly in patients with high-risk features. Further evidence is required for the role of amputation surgery and its impact on survival when initial interventions for revascularization fail to restore blood flow.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, Kim R, Jerome KR, Nalla AK, et al. . Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region — case series. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2012–2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee SG, Fralick M, Sholzberg M. Coagulopathy associated with COVID-19. Can Med Assoc J 2020;192:E583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. . Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gavriilaki E, Brodsky RA. Severe COVID-19 infection and thrombotic microangiopathy: success doesn't come easily. Br J Haematol 2020. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, Xia P, Cao W, Jiang W, et al. . Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ranucci M, Ballotta A, Di Dedda U, Bayshnikova E, Dei Poli M, Resta M, et al. . The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost 2020. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1111/jth.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bowles L, Platton S, Yartey N, Dave M, Lee K, Hart DP, et al. . Lupus anticoagulant and abnormal coagulation tests in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, Driggin E, et al. . COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;75:2950–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Menter T, Haslbauer JD, Nienhold R, Savic S, Hopfer H, Deigendesch N, et al. . Post-mortem examination of COVID19 patients reveals diffuse alveolar damage with severe capillary congestion and variegated findings of lungs and other organs suggesting vascular dysfunction. Histopathology 2020. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1111/his.14134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bellosta R, Luzzani L, Natalini G, Pegorer MA, Attisani L, Cossu LG, et al. . Acute limb ischemia in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Vasc Surg 2020. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.04.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]