Abstract

The Gustatory system enables animals to detect toxic bitter chemicals, which is critical for insects to survive food induced toxicity. Cucurbitacin is widely present in plants such as cucumber and gourds that acts as an anti-herbivore chemical and an insecticide. Cucurbitacin has a harmful effect on insect larvae as well. Although various beneficial effects of cucurbitacin such as alleviating hyperglycemia have also been documented, it is not clear what kinds of molecular sensors are required to detect cucurbitacin in nature. Cucurbitacin B, a major bitter component of bitter melon, was applied to induce action potentials from sensilla of a mouth part of the fly, labellum. Here we identify that only Gr33a is required for activating bitter-sensing gustatory receptor neurons by cucurbitacin B among available 26 Grs, 23 Irs, 11 Trp mutants, and 26 Gr-RNAi lines. We further investigated the difference between control and Gr33a mutant by analyzing binary food choice assay. We also measured toxic effect of Cucurbitacin B over 0.01 mM range. Our findings uncover the molecular sensor of cucurbitacin B in Drosophila melanogaster. We propose that the discarded shell of Cucurbitaceae can be developed to make a new insecticide.

Keywords: bitterness, Cucurbitaceae, cucurbitacin B, Drosophila melanogaster, toxicity

INTRODUCTION

Taste has immense roles for survival and reproduction as taste receptors embedded in the gustatory organs facilitate the animal to judge the quality of foods. Generally Drosophila melanogaster detect toxic chemicals as an aversive taste in bitter-sensing Gr66a + cells, pheromone, calcium-sensing ppk23+ cells, and edible chemicals as an attractive taste in sweet-sensing cells or water-sensing cells (Rimal and Lee, 2018). The induction of apoptosis from each type of gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs) interferes with avoidance or attraction to each type of tastants. Most bitter compounds such as caffeine, umbelliferone, coumarin, nicotine, strychnine, lobeline, L-canavanine, and berberine induce a strong response from bitter-sensing GRNs in Drosophila (Lee et al., 2009; 2012; 2015; Poudel and Lee, 2016; Poudel et al., 2015; Rimal and Lee, 2019; Shim et al., 2015; Sung et al., 2017; Weiss et al., 2011), whereas high concentrations of calcium and sodium salt induce a response from pheromone-sensing ppk23 + GRNs (Jaeger et al., 2018; Rimal and Lee, 2018). The gustatory processing is decoded in the higher brain center via subesophageal zone required for the behavioral response such as foraging, feeding, mating, and oviposition. Animals have immense ability to judge the toxic chemicals that help them to survive in the new environment (Ibanez et al., 2012). So far several family members including gustatory receptors (Grs), ionotropic receptors (Li et al., 2000), transient receptor potential channels (Trps), and pickpockets (ppks) are mainly functional to sense these toxic chemicals in nature (Dhakal and Lee, 2019; Fowler and Montell, 2013; Joseph and Carlson, 2015; Lee and Poudel, 2014; Rimal and Lee, 2018).

Cucurbitacin is one of the popular biochemical triterpenes present in the shell of plants such as pumpkins and gourds, which acts as an anti-herbivore chemical to protect themselves from insects. Various forms of cucurbitacin are present in variety of plants that impart bitter taste in plant foods. Moreover, cucurbitacin are known to regulate insect growth by inhibiting metamorphosis in D. melanogaster and Helicoverpa armigera (Zou et al., 2018). Apart from these, various biological activities such as antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-atherosclerosis, and anti-diabetic have been attributed to cucurbitacin (Kaushik et al., 2015).

Among the various 18 derivatives of cucurbitacin, cucurbitacin B, D, E, and I possess prominent antitumor effect. Furthermore, cucurbitacin B and D are most common in plants. Interestingly, cucurbitacin B is one of the most explored derivatives of cucurbitacin for its roles in the biological system (Garg et al., 2018). Most recently, cucurbitacin B is attributed to induce hypoglycemia by activating bitter taste receptor in intestinal L cells (Kim et al., 2018). Cucurbitacin B is present in traditional medicines such as Wilbrandia ebracteata, Begonia heracleifolia, Picrorhiza kurrooa, and Trichosanthes kirilowii (Chen et al., 2005). Moreover, cucurbitacin B has an adverse effect that avoid the ovipositional preferences to Ostrinia nubilalis, and Spodoptera exigua (Tallamy et al., 1997). Much attention has been paid to cucurbitacin B. However, the molecular sensor required to detect cucurbitacin has not been uncovered till date.

Drosophila taste sensation are mainly mediated through the channel gated mechanism endowed by the chemosensors enriched in the labellum, legs, ovipositor and wing margin (Lee and Poudel, 2014). The main taste organ, labellum, is embellished with hair-like taste sensilla which harbor different chemosensory neurons. The labellum is bipartite and each side of the labella is housed with 31 stratified taste sensilla (Stocker, 1994). The taste sensilla are denominated according to their length such as long L-type, intermediate I-type and short S-type (Hiroi et al., 2002; Shanbhag et al., 2001). The bitter chemical sensation is achieved by the two functional classes of bitter responsive sensilla, categorized as S-type and I-type. Variegated chemosensors are adorned in the GRNs that are present in the specific sensilla.

Grs are the first identified taste receptor in Drosophila genome (Clyne et al., 2000). The Grs are composed of 60 Gr genes, which forms 68 proteins via alternative splicing (Robertson et al., 2003). Among the 68 proteins, GR32a, GR33a, and GR66a are broadly expressed in all labellar bitter responsive sensilla. Due to their broad expression and functionality to detect a variety of chemicals by forming a heteromultimer with narrowly tuned receptors, these are also considered as co-receptor GRs (Lee and Poudel, 2014).

To uncover the molecular sensor required for the taste detection of cucurbitacin B (named it as cuc-B thereafter), we adopted genetic screening by performing electrophysiological examination. We further verified our new finding with behavioral and genetic analyses. We found that GR33a acts as a sensor required for the detection of cuc-B, which is essential for behavioral avoidance and neuronal firing in the peripheral neurons. Our findings serve fruitful avenue to develop cuc-B as an insect anti-feedant and insecticide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Drosophila stock

We obtained Gr2a1 (BL18415), Gr10a1 (BL29947), Gr22f1 (BL43859), Gr23a1 (BL19287), Gr28bMi (BL24190), Gr36b1 (BL24608), Gr36c1 (BL26496), Gr58b1 (BL29065), Gr59a1 (BL26125), Gr77a1 (BL26374), Gr93d1 (BL27800), Gr94a1 (BL17550), Gr97a1 (BL18949), Ir7g1 (BL42420), Ir10a1 (BL23842), Ir48a1 (BL26453), Ir48b1 (BL23473), Ir51b1 (BL10046), Ir52b1 (BL25212), Ir52c1 (BL24580), Ir56b1 (BL27818), Ir62a1 (BL32713), Ir67a1 (BL56583), Ir94d1 (BL33132), Ir94g1 (BL25551), and Ir94f1 (BL33095), Gr22b RNAi (BL64902), Gr22d RNAi (BL38248), Gr59f RNAi (BL61179), Gr63a RNAi (BL64997), Gr85a RNAi (BL67957), Gr93c RNAi (77349), Gr98c RNAi (BL36753), and Gr98d RNAi (BL77152) from the Bloomington stock center. We obtained Gr9a RNAi (VDRC102536), Gr10b RNAi (VDRC31151), Gr21a RNAi (VDRC104122), Gr22a RNAi (VDRC109329), Gr22c RNAi (VDRC104704), Gr33a RNAi (VDRC101615), Gr39a RNAi (VDRC10171), Gr47b RNAi (VDRC3493), Gr57a RNAi (VDRC45879), Gr58a RNAi (VDRC30096), Gr58c RNAi (VDRC29137), Gr59b RNAi (VDRC101219), Gr59d RNAi (VDRC2866), Gr59e RNAi (VDRC103954), Gr68a RNAi (VDRC105720), Gr92a RNAi (VDRC102611), Gr93b RNAi (VDRC12161), and Gr98a RNAi (VDRC100552). We obtained Gr22e1 from Kyoto Drosophila stock center. We obtained Gr28a1, Gr36a1, Gr39b1, Gr59c1, and Gr89a1 (Sung et al., 2017) from Korea Drosophila Re- source Center (Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology [GIST], Korea). We previously described Gr8a1 (Lee et al., 2012), Gr33a1, UAS-Gr33a, Gr33aGAL4 (Moon et al., 2009), Gr47a1 (Lee et al., 2015), Gr66aex83 (Moon et al., 2006), Gr93a3 (Lee et al., 2009), Gr98b1 (Shim et al., 2015), Ir7a1, Ir52a1, Ir56a1, Ir60b3, Ir94a1, Ir94c1, Ir94h1 (Rimal et al., 2019), trpA11 (Kwon et al., 2008), trpl29134 (Niemeyer et al., 1996), trpγ1 (Akitake et al., 2015), amo1 (Watnick et al., 2003), trp- ml2 (Venkatachalam et al., 2008), iav3621 (Gong et al., 2004), nan36a (Kim et al., 2003), trp343 (Wang et al., 2005), pyx3 (Lee et al., 2005), wtrwex , pain2 (Kim et al., 2010) flies. L. Voshall, C. Montell, and H. Amrein kindly provided Ir25a2, Ir76b1, and ΔGr32a flies respectively. We used w1118 flies as the “wild-type” control.

Chemical sources

Sucrose (CAS No. 57-50-1, Cat No. S9378), sulforhodamine B (CAS No. 3520-42-1, Cat No. 230162), and cucurbitacin B (CAS No. 6199-67-3, Cat No. PHL82226) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Brilliant blue FCF (CAS No. 3844-45-9, Cat No. 027-12842) was purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Japan).

Two-way food choice assay

We performed binary food choice assays as previously described (Poudel and Lee, 2018). Briefly 50 to 70 flies (3-6 days old) were starved in a 1% agarose only vial for 18 h in a dark and humid chamber. Two different food sources were prepared both containing 1% agarose: one containing 2 mM sucrose, and the other containing 2 mM sucrose with different concentrations of cuc-B. These food sources were mixed with a food dye, either blue coloring (brilliant blue FCF, 0.125 mg/ml) or red coloring (sulforhodamine B, 0.1 mg/ml). The two mixtures were distributed in 72-well microtiter dishes (Cat No. 438733; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in a zigzag pattern. We introduced the starved flies into the dish, and allowed them to feed for 90 min at room temperature in the same chamber. To score the flies, we transferred them to a freezer and then analyzed the color of their abdomens under a stereomicroscope. Blue (NB), red (NR), or purple (NP) flies were classified. The preference index (P.I.) was calculated according to the following equation: (NB + 0.5NP)/(NR + NB + NP) or (NR + 0.5NP)/(NR + NB + NP), depending on the dye/tastant combinations. P.I.s = 1.0 and 0 indicated complete preferences for one or the other food. A P.I. = 0.5 indicates no bias between the two foods. We have confirmed that the dyes have no roles for this choice.

Electrophysiology

We performed tip recording assays as previously described (Lee et al., 2009). We anesthetized 4- to 7-day-old flies by putting them on ice and then inserted a reference glass electrode filled with Ringer’s solution into the thorax of the flies, extending the electrode towards their proboscis. We prepared for 5 to 6 live insects per each set-up and repeated the same procedure for several rounds at different days. We stimulated the sensilla for 5 s with tastants dissolved in 1 mM KCl for S-type and I-type sensilla or 30 mM tricholine citrate for L-type sensilla as an electrolyte in recording pipettes (10-20 μm tip diameter). The recording electrode was connected to a preamplifier (Taste PROBE; Syntech, The Netherlands), and the signals were collected and amplified by 10×, using a signal connection interface box (Syntech) in conjunction with a 100 to 3,000 Hz band-pass filter. Recordings of action potentials were acquired using a 12-kHz sampling rate and analyzed using Autospike 3.1 software (Syntech). Each consecutive recording was performed with about 1 min of gap between each stimulation. The trial numbers (n) in each figure indicate the number of insects.

Survival assay

We performed survival assay as previously described (Rimal and Lee, 2018). Briefly, we used 10 male and 10 female flies in an experimental set. The flies were placed in standard fly culture food containing indicated concentrations of cuc-B and kept at 25°C in a 60% humidity chamber. The number of dead flies were counted every 12 h and the viable flies were transferred to new vials containing the same food source for 20 days. The experiment was carried out for four times.

Statistical analysis

All error bars represent SEM. Single factor ANOVA with Scheffe’s analysis was used as a post hoc test to compare multiple sets of data. For survival assay, we used Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to test significance. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Statistical analyses were performed with the OriginPro 8 for the Windows (ver. 8.0932; OriginLab Corporation, USA).

RESULTS

Flies sense cuc-B as an anti-feedant

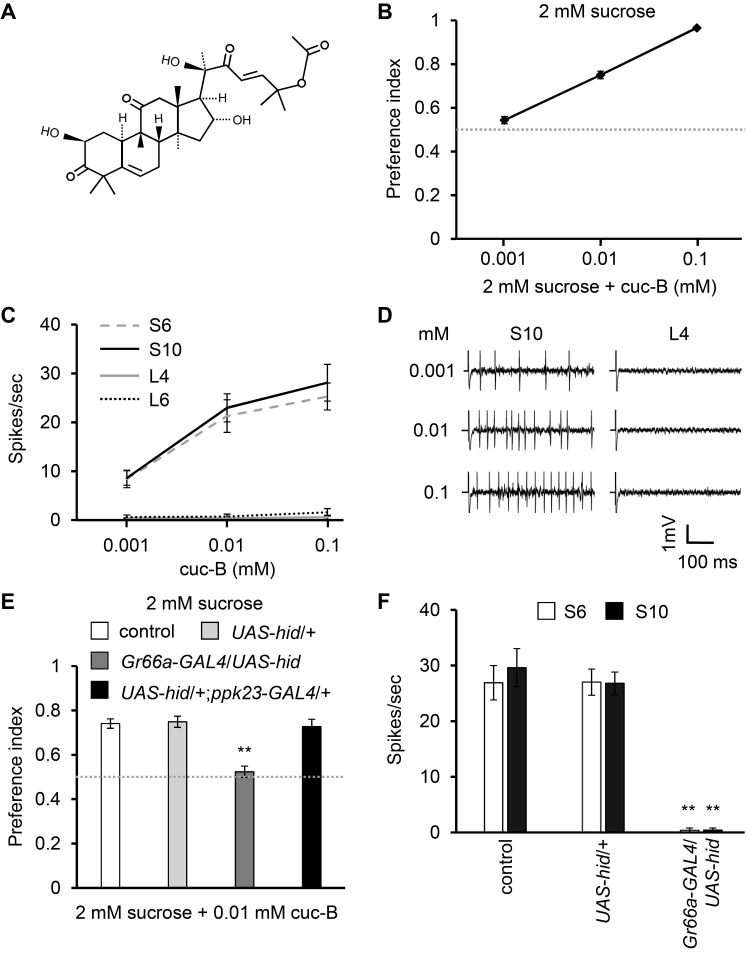

Cucurbitacin acts as a potential toxin to the insects (Yousaf et al., 2018). To reveal how flies sense cuc-B (Fig. 1A), we performed binary food choice assay. When we allowed the flies to choose between 2 mM sucrose and 2 mM sucrose plus variable concentration ranges of cuc-B, flies showed unbiased at 0.001 mM, but started to avoid 0.01 to 0.1 mM cuc-B in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 1B). This provides the evidence that cuc-B can work as an anti-feedant. Next, we elicited cuc-B–induced action potentials from two representative S-type sensilla (S6 and S10 from Tanimura nomenclature) and L-type sensilla (L4 and L6) (Figs. 1C and 1D). We observed that minimal concentrations of cuc-B can induce remarkable neuronal firing from S-type sensilla, but not from L-type sensilla (Figs. 1C and 1D). This indicates that it activated bitter-sensing GRNs housed in S-type sensilla, based on the avoidance behavior and strong action potentials from S-type sensilla. To further verify the neuronal participation responsible for the production of action potentials, we ablated bitter-sensing or calcium-sensing GRNs by expressing a pro-apoptotic gene hid under the control of bitter-sensing Gr66a-GAL4 (Thorne et al., 2004) or calcium-sensing ppk23-GAL4 (Lee et al., 2018; Rimal and Lee, 2018) drivers. Bitter-sensing GRNs-ablated flies failed to avoid 0.01 mM cuc-B in a binary food choice assay, compared with wild-type control or UAS-hid only parent strain (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the other aversive ppk23 + GRNs-ablated flies normally avoided cuc-B-laced food at the similar level of control. This indicates that the taste of cuc-B is transduced through bitter responsive GRNs in flies. Congruently, the responses from S-type sensilla were completely vanished in bitter-sensing GRNs-ablated flies, when we performed electrophysiological examination by stimulating the S6 and S10 with 0.01 mM cuc-B (Fig. 1F). These results suggest that the anti-feedant effect of cuc-B is mediated through bitter-sensing GRNs at the level of behavior and physiology.

Fig. 1. cuc-B structure, responses to cuc-B in wild-type control and ablated flies.

(A) Structure of cuc-B. (B) Binary food choice assay showing preferences of flies to 2 mM sucrose vs 2 mM sucrose plus the indicated concentrations of cuc-B (n = 4-6). (C) Average frequencies of action potentials elicited from S6, S10, L4, and L6 sensilla with the indicated concentrations of cucurbitacin (n = 15-18). (D) Representative sample traces obtained from S10 and L4 sensilla. (E) Binary food choice assays with control, parent strain (UAS-hid/+), each bitter-sensing GRNs- or calcium-sensing GRNs-ablated flies (n = 4-6). (F) Average frequencies of action potentials elicited from S6 and S10 sensilla with 0.1 mM cuc-B (n = 10-14). All error bars represent SEM. Single factor ANOVA with Scheffe’s analysis was used as a post hoc test to compare multiple sets of data. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (**P < 0.01).

Gustatory receptor is required for the taste sensation of cuc-B

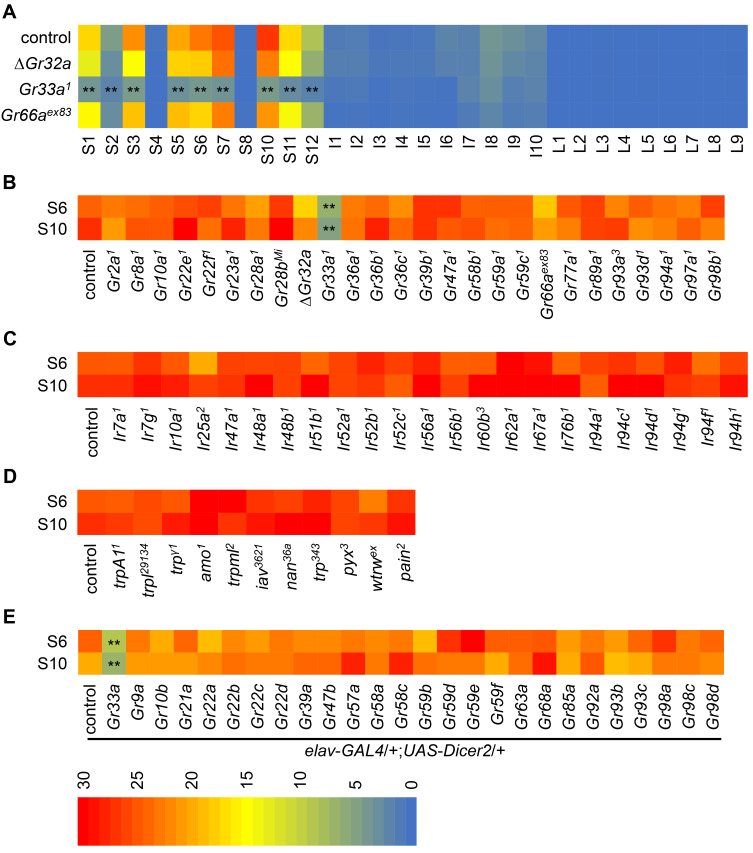

To evaluate neuronal activity to cuc-B, we carried out sensilla mapping with 0.1 mM cuc-B. The stimulus elicited more than 10 spikes per second from most S-type sensilla except S4 and S8 which are mostly sensitive to calcium and sodium salt (Rimal and Lee, 2018; Zhang et al., 2013). These include S1, S3, S5, S6, S7, S10, and S11 sensilla, but reduced levels of action potential frequencies from S2 and S12 sensilla. However, we did not get any action potentials from L-type sensilla and almost a null response from I-type sensilla (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Screening of candidate mutants to the response of cuc-B.

(A) Mapping of the sensilla to the electrophysiological response with 0.1 mM cuc-B (n = 20-30). The nomenclature system is based on the Tanimura study (Hiroi et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2015). Depending on the length of sensilla, there are three types such as long L-type, intermediate I-type and short S-type. (B) Screening of indicated Gr mutant lines with 0.1 mM cuc-B by tip recording from S6 and S10 sensilla (n = 10-13). (C) Screening of indicated Ir mutants with 0.1 mM cuc-B by tip recording from S6 and S10 sensilla (n = 10-11). (D) Screening of indicated Trp mutants with 0.1 mM cuc-B by tip recording from S6 and S10 sensilla (n = 10-12). (E) Screening of indicated Gr-RNAi lines which are crossed with elav-GAL4;UAS-Dicer2 with 0.1 mM cuc-B by tip recording from S6 and S10 sensilla (n = 10-12). All error bars represent SEM. Single factor ANOVA with Scheffe’s analysis was used as a post hoc test to compare multiple sets of data. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (**P < 0.01).

To unravel the sensor required for the detection of cuc-B, we screened candidate gustatory receptors such as 26 Grs, 23 Irs, and 11 Trp mutants (Figs. 2B-2D). These include broadly required gustatory receptors such as Gr32a, Gr33a, Gr66a, and broadly required ionotropic receptors Ir25a, and Ir76b (Figs. 2B and 2C). From this screening, we identified that Gr33a1 was the only mutant that have significantly reduced action potentials in S6 and S10 to cuc-B. Furthermore, we investigated all the sensilla from Gr33a1 and found highly reduced responses to cuc-B from all the S-type sensilla, compared with control (Fig. 2A). While broadly tuned the other two Grs such as Gr32a and Gr66a were dispensable to sense cuc-B at the level of tip recording (Figs. 2A and 2B). In addition, 23 Irs and 11 Trp mutants had normal physiological responses to cuc-B (Figs. 2C and 2D). Next, we decided to test all possible Gr-RNAi lines to find any additional members of cucurbitacin receptor. This covers 28 GR proteins. 26 Gr-RNAi lines including Gr33a RNAi were tested after crossing with elav-GAL4;UAS-Dicer2 (elav > Gr-RNAi) (Fig. 2E). Among 68 GRs, we covered 59 GRs excluding 9 sweet-sensing receptor proteins. However, except Gr33a mutant, there is no defect with other Gr mutants. This indicates that the anti-feedant effect of cuc-B is mediated by GR33a, but not IRs or TRPs.

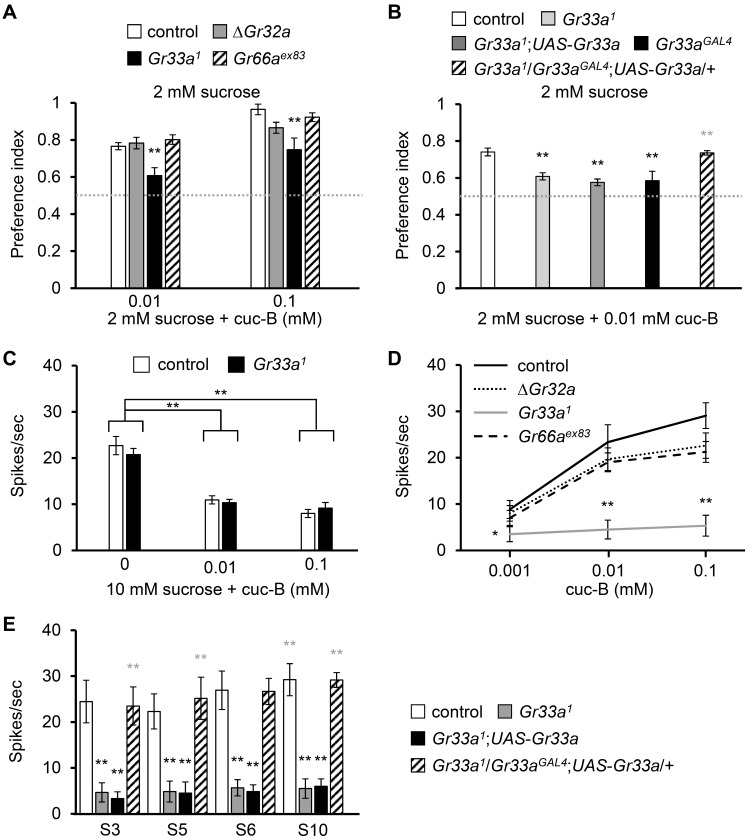

Gr33a is indispensable for behavioral avoidance to cuc-B

To further evaluate the role of Gr33a in avoidance to cuc-B, we tested binary food choice assays using 0.01 and 0.1 mM cuc-B (Fig. 3A). Gr33a 1 had significant defects to avoid cuc-B, whereas other broadly expressed Gr mutants, ΔGr32a and Gr66a ex83 showed normal behavioral avoidance as of control flies (Fig. 3A). ΔGr32a has relatively reduced avoidance at 0.1 mM cuc-B, but it was not statistically significant. The defect of Gr33a1 was confirmed by the other knock-in GAL4 reporter mutant, Gr33a GAL4 (Fig. 3B). The defect of Gr33a1 to avoid cuc-B was successfully recovered by expressing wild type cDNA of Gr33a under the control of Gr33a GAL4, but the negative control (Gr33a 1;UAS-Gr33a) had the same defect as Gr33a 1 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Gr33a is indispensable for behavioral avoidance and action potentials induced by cuc-B.

(A) Binary food choice assays with the indicated concentrations of cuc-B and indicated flies (n = 6-8). (B) Rescue of Gr33a1 defect in binary food choice assay by allowing the control, parent, and rescue strains to choose between 2 mM sucrose versus 2 mM sucrose plus 0.01 mM cuc-B (n = 4-6). (C) Average frequencies of action potential elicited by providing 10 mM sucrose and the indicated concentrations of cuc-B on L4 sensilla (n = 17- 21). (D) Average frequencies of action potential elicited from S10 sensilla of control and the indicated ∆Gr32a, Gr33a1,and Gr66aex83 mutants in a range of 0.001-0.1 mM cuc-B (n = 10-13). (E) Rescue of Gr33a1 defect in tip recording by expressing wild type cDNA of Gr33a under control of Gr33aGAL4 (n = 10-12). All error bars represent SEM. Single factor ANOVA with Scheffe’s analysis was used as a post hoc test to compare multiple sets of data. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Black asterisks indicate statistical comparison with control, but gray asterisks in Figs. 3B and 3E indicate statistical comparison with the Gr33a1.

However, Gr33a mutant still slightly avoided cuc-B (Fig. 3A). This may be caused by sugar inhibition of most bitter compounds (Moon et al., 2009). To verify this possibility, we tested L-type sensilla applying 10 mM sucrose with or without cuc-B (Fig. 3C). The action potentials induced by 10 mM sucrose from L4 were around 20 spikes per second. However, this response was diminished by the addition of 0.01 or 0.1 mM cuc-B in control flies. Furthermore, the cuc-B induced inhibition of sugar GRNs is not dependent on Gr33a 1, because this effect is not attenuated in Gr33a mutants. We also further confirmed the defect of Gr33a mutant with different ranges of cuc-B in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 3D). Two other broadly required Gr mutants, ΔGr32a and Gr66a ex83 have normal response to different ranges of cuc-B (Fig. 3D). This physiological defect can also be recovered by the expression of wild-type cDNA Gr33a under the control of Gr33a GAL4 (Fig. 3E).

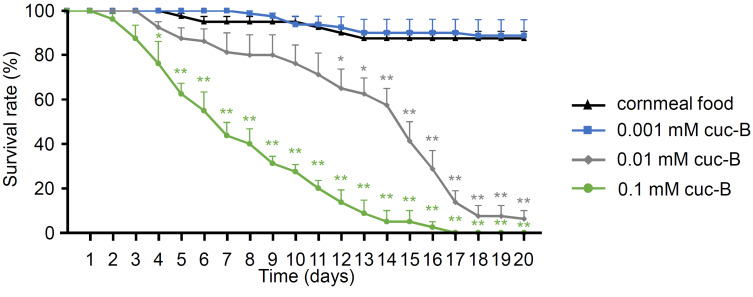

cuc-B has an insecticidal effect

Because we detected flies to avoid 0.01-0.1 mM cuc-B, we tested whether cuc-B is toxic in this range. We compared the survival of flies maintained on cornmeal food or cornmeal food mixed with 0.001-0.1 mM cuc-B (Fig. 4). There was no lethality with 0.001 mM cuc-B until 20 days, but we found that over 0.01 mM cuc-B clearly decreased viability in a dose dependent manner. Feeding 0.01 mM cuc-B had moderate lethality, so the times in which 50% died (LT50) were 13.50 ± 1.19 days. Furthermore, LT50 of 0.1 mM cuc-B feeding were 6.50 ± 0.85 days.

Fig. 4. Toxicity test with cuc-B.

Survival of control flies fed cornmeal food or cornmeal food mixed with indicated concentrations of cuc-B (n

= 4). All error bars represent SEM. Single factor ANOVA with Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used as a post hoc test to compare tested condition with control feeding. Asterisks indicate statistical significance with control (*P< 0.05, **P< 0.01).

DISCUSSION

Various kinds of chemosensors in insects are co-evolving with plant defense mechanisms. Grs are one of the epitomes that display how animals are being protected by granting an excellent quality of sensation, so they work as an interface between animals and their niche. GRs have a broad range of activity to decide feeding and oviposition preferences in Drosophila. Among the 68 GRs, closely related nine GRs are known to have important biological roles in the sensation of sweet compounds (Chyb et al., 2003; Dahanukar et al., 2007; Miyamoto et al., 2012), while many other GRs are known to be required for the detection of toxic bitter chemicals (Lee and Poudel, 2014; Rimal and Lee, 2018). Broadly expressed GRs such as GR32a, GR33a, and GR66a share biological functions to sense plethora of toxic bitter chemicals in the environment by forming a heteromultimeric unit (Shim et al., 2015; Sung et al., 2017). At least one of these 3 GRs are essential to recapitulate functional GR heteromultimer in an in vitro heterologous system (Shim et al., 2015; Sung et al., 2017). Among these broadly tuned GRs, only GR33a imparts the taste avoidance of cuc-B at the level of behavior and tip recording. The other narrowly tuned GRs tested were dispensable. Here we tested total 26 Gr null mutants (which cover 31 GRs due to alternative splicing) and 26 Gr RNAi lines (which cover 29 GRs including GR33a). These results provide two possible explanations. One is that there may be any unidentified chemoreceptor category to respond to cuc-B. It is possible that multiple chemoreceptors separately respond to cuc-B, because cuc-B is a relatively big compound and possible ligand binding sites can be multiple. Indeed, there were residual spikes in Gr33a mutants, compared with bitter GRNs-ablated flies (Gr66a-GAL4/UAS-hid). The defect of the behavioral avoidance is relatively milder in Gr33a mutants than Gr66a-GAL4/UAS-hid flies, although these two conditions are not statistically significant. The other possible explanation is that RNAi experiment is incomplete to ablate gene function. The resolution of this knock-down experiment may be not enough to find additional member, although we provide negative control, Gr33a RNAi.

Various chemicals are present in the plants such as phenols, alkaloids, terpenes, and flavonoids which have anti-herbivore and insecticidal effects on phytophagous insects (Adeyemi, 2010). Cucurbitacin, a class of terpenes, have important biological roles including insecticidal effect and internal regulation in animal organs. It would be beneficial to target the specific GRs to develop a new highly potent insecticide based on a cucurbitacin-based compound.

Cuc-B is relatively abundant in the shell of Cucurbitaceae, which is usually trashed in houses and industries. It is worth to develop a way to make good use of these discarded resources.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nick DeBeaubien in UCSB for valuable comments. This work is supported by grants to Y.L. from the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1A2B6004202). S.R. and S.D. were supported by the Global Scholarship Program for Foreign Graduate Students at Kookmin University in Korea.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.L. conceived and designed the experiments. S.R., J.S., and S.D. performed the experiments. S.R. and Y.L. wrote the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Adeyemi M.H. The potential of secondary metabolites in plant material as deterents against insect pests: a review. Afr. J. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010;4:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Akitake B., Ren Q., Boiko N., Ni J., Sokabe T., Stockand J.D., Eaton B.A., Montell C. Coordination and fine motor control depend on Drosophila TRP. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7288. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.C., Chiu M.H., Nie R.L., Cordell G.A., Qiu S.X. Cucurbitacins and cucurbitane glycosides: structures and biological activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2005;22:386–399. doi: 10.1039/b418841c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyb S., Dahanukar A., Wickens A., Carlson J.R. Drosophila Gr5a encodes a taste receptor tuned to trehalose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:14526–14530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2135339100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne P.J., Warr C.G., Carlson J.R. Candidate taste receptors in Drosophila. Science. 2000;287:1830–1834. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahanukar A., Lei Y.T., Kwon J.Y., Carlson J.R. Two Gr genes underlie sugar reception in Drosophila. Neuron. 2007;56:503–516. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal S., Lee Y. Transient receptor potential channels and metabolism. Mol. Cells. 2019;42:569. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler M.A., Montell C. Drosophila TRP channels and animal behavior. Life Sci. 2013;92:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg S., Kaul S.C., Wadhwa R. Cucurbitacin B and cancer intervention: chemistry, biology and mechanisms. Int. J. Oncol. 2018;52:19–37. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.4203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Z., Son W., Chung Y.D., Kim J., Shin D.W., McClung C.A., Lee Y., Lee H.W., Chang D.J., Kaang B.K., et al. Two interdependent TRPV channel subunits, inactive and Nanchung, mediate hearing in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:9059–9066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1645-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi M., Marion-Poll F., Tanimura T. Differentiated response to sugars among labellar chemosensilla in Drosophila. Zoolog. Sci. 2002;19:1009–1019. doi: 10.2108/zsj.19.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez S., Gallet C., Després L. Plant insecticidal toxins in ecological networks. Toxins. 2012;4:228–243. doi: 10.3390/toxins4040228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger A.H., Stanley M., Weiss Z.F., Musso P.Y., Chan R.C., Zhang H., Feldman-Kiss D., Gordon M.D. A complex peripheral code for salt taste in Drosophila. Elife. 2018;7:e37167. doi: 10.7554/eLife.37167.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R.M., Carlson J.R. Drosophila chemoreceptors: a molecular interface between the chemical world and the brain. Trends Genet. 2015;31:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik U., Aeri V., Mir S.R. Cucurbitacins-an insight into medicinal leads from nature. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2015;9:12. doi: 10.4103/0973-7847.156314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Chung Y.D., Park D.Y., Choi S., Shin D.W., Soh H., Lee H.W., Son W., Yim J., Park C.S., et al. A TRPV family ion channel required for hearing in Drosophila. Nature. 2003;424:81. doi: 10.1038/nature01733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.H., Lee I.S., Park J.Y., Kim Y., Jang H.J. Cucurbitacin B induces hypoglycemic effect in diabetic mice by regulation of AMP-activated protein kinase alpha and glucagon-like peptide-1 via bitter taste receptor signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:1071. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.H., Lee Y., Akitake B., Woodward O.M., Guggino W.B., Montell C. Drosophila TRPA1 channel mediates chemical avoidance in gustatory receptor neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:8440–8445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001425107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y., Shim H.S., Wang X., Montell C. Control of thermotactic behavior via coupling of a TRP channel to a phospholipase C signaling cascade. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:871. doi: 10.1038/nn.2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Kang M.J., Shim J., Cheong C.U., Moon S.J., Montell C. Gustatory receptors required for avoiding the insecticide L-canavanine. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:1429–1435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4630-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Lee Y., Lee J., Bang S., Hyun S., Kang J., Hong S.T., Bae E., Kaang B.K., Kim J. Pyrexia is a new thermal transient receptor potential channel endowing tolerance to high temperatures in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:305. doi: 10.1038/ng1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Moon S.J., Montell C. Multiple gustatory receptors required for the caffeine response in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:4495–4500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811744106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Moon S.J., Wang Y., Montell C. A Drosophila gustatory receptor required for strychnine sensation. Chem. Senses. 2015;40:525–533. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjv038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Poudel S. Taste sensation in Drosophila melanoganster. Hanyang Med. Rev. 2014;34:130–136. doi: 10.7599/hmr.2014.34.3.130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Poudel S., Kim Y., Thakur D., Montell C. Calcium taste avoidance in Drosophila. Neuron. 2018;97:67–74.:e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Chaney S., Forte M., Hirsh J. Ectopic G-protein expression in dopamine and serotonin neurons blocks cocaine sensitization in Drosophila melanogaster. Curr. Biol. 2000;10:211–214. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto T., Slone J., Song X., Amrein H. A fructose receptor functions as a nutrient sensor in the Drosophila brain. Cell. 2012;151:1113–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S.J., Köttgen M., Jiao Y., Xu H., Montell C. A taste receptor required for the caffeine response in vivo. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1812–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S.J., Lee Y., Jiao Y., Montell C. A Drosophila gustatory receptor essential for aversive taste and inhibiting male-to-male courtship. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer B.A., Suzuki E., Scott K., Jalink K., Zuker C.S. The Drosophila light-activated conductance is composed of the two channels TRP and TRPL. Cell. 1996;85:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel S., Kim Y., Kim Y.T., Lee Y. Gustatory receptors required for sensing umbelliferone in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015;66:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel S., Lee Y. Gustatory receptors required for avoiding the toxic compound coumarin in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Cells. 2016;39:310. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2016.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel S., Lee Y. Impaired taste associative memory and memory enhancement by feeding omija in Parkinson's disease fly model. Mol. Cells. 2018;41:646. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2018.0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal S., Lee Y. The multidimensional ionotropic receptors of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol. Biol. 2018;27:1–7. doi: 10.1111/imb.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal S., Lee Y. Molecular sensor of nicotine in taste of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019;111:103178. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal S., Sang J., Poudel S., Thakur D., Montell C., Lee Y. Mechanism of acetic acid gustatory repulsion in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1432–1442.:e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson H.M., Warr C.G., Carlson J.R. Molecular evolution of the insect chemoreceptor gene superfamily in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:14537–14542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335847100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag S., Park S.K., Pikielny C., Steinbrecht R. Gustatory organs of Drosophila melanogaster: fine structure and expression of the putative odorant-binding protein PBPRP2. Cell Tissue Res. 2001;304:423–437. doi: 10.1007/s004410100388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim J., Lee Y., Jeong Y.T., Kim Y., Lee M.G., Montell C., Moon S.J. The full repertoire of Drosophila gustatory receptors for detecting an aversive compound. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8867. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R.F. The organization of the chemosensory system in Drosophila melanogaster: a rewiew. Cell Tissue Res. 1994;275:3–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00305372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung H.Y., Jeong Y.T., Lim J.Y., Kim H., Oh S.M., Hwang S.W., Kwon J.Y., Moon S.J. Heterogeneity in the Drosophila gustatory receptor complexes that detect aversive compounds. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1484. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01639-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallamy D.W., Stull J., Ehresman N.P., Gorski P.M., Mason C.E. Cucurbitacins as feeding and oviposition deterrents to insects. Environ. Entomol. 1997;26:678–683. doi: 10.1093/ee/26.3.678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne N., Chromey C., Bray S., Amrein H. Taste perception and coding in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K., Long A.A., Elsaesser R., Nikolaeva D., Broadie K., Montell C. Motor deficit in a Drosophila model of mucolipidosis type IV due to defective clearance of apoptotic cells. Cell. 2008;135:838–851. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Jiao Y., Montell C. Dissecting independent channel and scaffolding roles of the Drosophila transient receptor potential channel. J. Cell Biol. 2005;171:685–694. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick T.J., Jin Y., Matunis E., Kernan M.J., Montell C. A flagellar polycystin-2 homolog required for male fertility in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:2179–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss L.A., Dahanukar A., Kwon J.Y., Banerjee D., Carlson J.R. The molecular and cellular basis of bitter taste in Drosophila. Neuron. 2011;69:258–272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf H.K., Shan T., Chen X., Ma K., Shi X., Desneux N., Biondi A., Gao X. Impact of the secondary plant metabolite Cucurbitacin B on the demographical traits of the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16473. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34821-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.V., Ni J., Montell C. The molecular basis for attractive salt-taste coding in Drosophila. Science. 2013;340:1334–1338. doi: 10.1126/science.1234133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C., Liu G., Liu S., Liu S., Song Q., Wang J., Feng Q., Su Y., Li S. Cucurbitacin B acts a potential insect growth regulator by antagonizing 20-hydroxyecdysone activity. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018;74:1394–1403. doi: 10.1002/ps.4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]