Abstract

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) trials often implement adherence counseling to support product use. Because counseling fidelity can vary significantly across providers and time, fidelity monitoring can ensure that counseling is delivered as designed. We describe the process, feasibility, and outcomes of monitoring Options counseling fidelity in an open label study of the dapivirine vaginal ring MTN-025/HOPE. After their initial training, 63 counselors from 14 sites in Sub-Sahara Africa audio-recorded counseling sessions with study participants. Sessions were rated for fidelity by a New York-based team that included bilingual emigres from the study countries who were monitored monthly to ensure inter-rater reliability. Completed session rating forms were sent to counselors to provide feedback and counseling difficulties were discussed during monthly coaching calls. Of 1,456 study participants, 85.7% consented to at least one session, and 20% to all sessions, being audio-recorded. Among 9,926 study visits in which Options was expected to occur, 5,366 (54.1%) Options sessions were audio-recorded, of which 1,238 (23.1%) were reviewed for fidelity and 1,039 (83.9%) were rated as “good” or “fair.” Eleven counselors who failed to consistently deliver the intervention were reassigned to back-up status. This study demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of monitoring counseling fidelity using audio-recordings in a multi-site, multi-language, multi-country PrEP trial. Given the investment necessary to conduct such trials, providing counseling oversight is highly warranted.

Keywords: counseling, fidelity, motivational interviewing, HIV, Africa

Introduction

Poor adherence and misleading self-reports of product use have impeded accurate assessment of the efficacy of new HIV PrEP products (Marrazzo et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2010; Baeten et al., 2016; Corneli et al., 2014) and even led to the suspension of study arms due to apparent product futility (Marrazzo et al., 2015), resulting in significant scientific and financial losses. To improve adherence, there has been a push to standardize adherence counseling (Amico et al., 2013) and, more recently, to develop new adherence counseling interventions based on approaches proven to improve adherence in other health behaviors (Amico et al., 2012). Biomedical tests such as measurement of drug levels which are used to monitor adherence are subject to strict quality control procedures to ensure assay reproducibility. However, the same rigor has not been applied to ensuring counseling integrity even though studies have shown that it is difficult for counselors to learn new counseling approaches (Balán et al., 2014; Nishita et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2013; Wilcox et al., 2010; Moyers et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2015) and that they often return to their usual approaches shortly after training unless ongoing monitoring and coaching are included to preserve fidelity (Schwalbe, Hy & Zweben, 2014).

In international contexts, the challenge of training counselors to deliver counseling with fidelity throughout the duration of a study is further complicated because the intervention must be delivered in multiple languages and across different cultural contexts. Further, there is often a lack of local expertise to monitor and support the specific intervention’s implementation. Monitoring the fidelity with which counselors deliver an intervention ensures that key components are consistently delivered in much the same way as use of positive and negative controls ensure assay quality in laboratory science. Preservation of fidelity is especially important if the intervention is evidence-based and there are known, active components of the counseling approach that must be retained for it to maintain its efficacy (McHugh & Barlow, 2010).

Approaches to maximize fidelity to counseling interventions have been reported (Bellg et al., 2004; Gearing et al., 2011; Baer et al., 2007), and some PrEP studies have used a variety of these approaches to attain fidelity. For example, researchers have developed intervention manuals, conducted in-person trainings (usually 1 to 3 days in duration, with booster trainings if necessary), and provided ongoing coaching or mentoring (typically occurring every 4–6 weeks) (Amico et al., 2013). Some investigators have used self-reported fidelity checklists of key counseling session tasks (Safren et al., 2015) and live observation of a small percentage of counseling sessions (Kevany et al., 2016).

Audio-recordings provide a more accurate assessment of counseling fidelity than the counselor’s self-report (Hogue et al., 2015; Martino et al., 2009; Carroll, Nich & Rounsaville, 1998; Hurlburt et al., 2010), are less intrusive than live observation, and allow for more frequent monitoring of sessions with minimal staff burden. However, unlike behavioral intervention trials where the use of audio-recordings to monitor fidelity is the norm, only one PrEP study has reported the use of audio-recordings to monitor counseling fidelity. The authors found that, half of the counselors met fidelity criteria on less than 50% of sessions, including a few who rarely met fidelity criteria for any session (Balán et al., 2014). These findings are not unusual, as counseling fidelity can vary across providers and disciplines (Nishita et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2013; Wilcox et al., 2010), and poorer fidelity is often reported when providers have lower levels of formal counseling training (Campbell et al., 2013; Moyers et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2015).

This manuscript seeks to inform the future implementation of evidence-based counseling interventions in PrEP and other biomedical HIV prevention trials to capitalize on the promise of integrated bio-behavioral interventions. To this end, it describes the program implemented to establish and maintain fidelity to a counseling intervention developed to maximize adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring or any other HIV risk reduction approach selected by participants in MTN-025, the HIV Open-label Prevention Extension (HOPE) Study. This program was informed by the recommendations of the Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health’s Behavior Change Consortium (BCC) (Bellg et al., 2004) and Gearing, et al. (2011) but was adapted for use outside a behavioral intervention trial (See Table 1). In this manuscript we will, (1) describe the approaches used to train and coach counselors and monitor their fidelity to Options, which was delivered by 63 counselors in five languages and 14 study sites across four countries in Sub-Saharan Africa; (2) demonstrate the feasibility of this process by reporting the numbers of sessions recorded and reviewed across study sites, the frequency of providing written feedback to study counselors, and the duration of time between session uploads and counselors receipt of feedback; and (3) provide initial findings on the counseling fidelity maintained during the HOPE Study.

Table 1.

Adherence Counseling Fidelity Monitoring Process for MTN-025 (The HOPE Study)

| Design | Training | Monitoring | Receipt of intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

Theoretical foundation

|

In-person trainings

|

Fidelity monitoring procedures Rating forms

|

Attendance

|

Methods

Overview of HOPE

MTN-025/HOPE is an open label extension trial to assess the continued safety of and adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring (25mg) for the prevention of HIV-1 acquisition in former MTN-020/ASPIRE participants. During the MTN-020 trial, the ring was found to reduce the risk of HIV approximately 30% overall and by more than 50% among participants with evidence of greater product use (Baeten et al., 2016). The HOPE trial was conducted at fourteen study sites in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. Women who had participated in ASPIRE and were HIV-uninfected, not pregnant, and met other eligibility criteria were offered enrollment in HOPE. Participants could opt to enroll in the study and select whether to use the ring and/or another HIV prevention method. Enrollment for HOPE occurred between July 2016 and May 2018.

Participants were offered monthly use of the dapivirine ring for a period of 12 months. The follow-up schedule included visits at months 1–3, and quarterly visits at months 6, 9, and 12. A final visit was conducted approximately one month after product use ended. At the quarterly visits, participants were offered three rings to take home and instructed to replace them monthly. Participants received adherence counseling at every study visit, along with clinical, behavioral, and laboratory assessments, including HIV/STI testing and dapivirine drug level detection using hair and plasma samples. Participants who chose to use the ring were asked to return used rings at each study visit. The rings were analyzed for residual drug levels as a secondary adherence analysis; levels were scaled from 0 (low or no use) to 3 (high use) based on the amount of drug that remained in each ring and presented to participants during counseling sessions as a range from 0 (no protection) to 3 (high protection). As part of the adherence counseling, participants were informed of their residual drug levels upon returning for the following visit, starting at Month 3.

The institutional review boards (IRB) at all study sites approved the MTN-025/HOPE study. Due to differing IRB requirements and a reluctance to revise and resubmit the consent forms already approved by the site IRBs, a separate approval was obtained for audio recording counseling sessions for quality control. These IRB differences resulted in consent procedures for the recordings that varied across sites: four sites required signed consent from participants to record sessions, while nine allowed for verbal consent following the presentation of an information sheet about the recordings. At one site, administrative approval by the IRB was sufficient and required only verbal consent from the participant, with no formal consent form or information sheet. Delays in IRB approval at one site impeded its ability to record sessions for the first 10 weeks of enrollment. Participants had to give consent for the session to be recorded and could decline without it impacting their participation in the trial. Consent for audio-recording was obtained during the Enrollment Visit as part of the HOPE study consent process.

Adherence Counseling Intervention

The adherence counseling intervention (called Options in HIV Prevention) is based on Motivational Interviewing (MI) principles [25] and was developed specifically for HOPE to support adherence to a participant-selected, HIV risk reduction plan, regardless of whether this plan included use of the dapivirine vaginal ring. A brief overview of MI and related research findings that were considered in the design of Options are included in Box 1. Given that proficiency in MI can be difficult to attain among counselors with limited formal counseling training (Campbell et al., 2013; Moyers et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2015) and a lack of local MI experts to provide detailed coaching in the study languages, the goal was to embed critical components of MI into Options. Such components included assuming a client-centered approach, avoiding counselor behaviors that tend to evoke sustain talk, and frequent use of simple counselor behaviors that evoke change talk (see Box 1 for descriptions of sustain talk and change talk).

Box 1. Overview of Motivational Interviewing (MI).

MI is “a collaborative, goal-oriented method of communication that is designed to strengthen an individual’s motivation for and movement toward a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own arguments for change.” (Miller & Rollnick, 2013). MI is guided by four processes: Engagement (establishing the therapeutic relationship), Focusing (deciding the area on which to focus the work), Evocation (evocation of the patient’s reasons, need, desire, ability, and commitment to change), and Planning (collaboratively developing a plan to achieve desired goals). Throughout the sessions, the clinician guides rather than pushes the patient towards change, sidestepping resistance and actively working with the patient’s strengths to build self-efficacy towards the desired outcome. MI uses standard tools of counseling and psychotherapy (i.e., open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, and summaries) strategically to elicit and reinforce change talk. Change talk is verbalizations from a patient that argue against the status quo (i.e., “I can’t keep doing what I am doing, I really don’t want be HIV positive”) or for behavior change (i.e., “I have to take better care of myself so that I don’t get HIV”).

Research findings on mechanisms of action in MI.

Process research on MI demonstrates that more change talk (Moyers et al., 2009; Vader et al., 2010) and less sustain talk (statements from a client that argue against change, for example, “Sex feels so much better when I don’t use a condom”) during a session are related to better outcomes (Moyers et al., 2009; Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009). Research has also found that counselor behaviors such as advising, confronting, directing, and warning clients are associated with greater sustain talk (Magill et al., 2014; Moyers & Martin, 2006), whereas counselor behaviors such as affirming strengths or effort, emphasizing client control, and supporting are associated with increased change talk (Moyers & Martin, 2006; Magill & Apodaca, 2009). Thus, to facilitate behavior change, the goal of an MI counselor is to interact with the client in a manner that facilitates change talk and inhibits sustain talk. Then, once the client expresses a commitment to change, the counselor works with the client to collaboratively establish a change plan, maximizing self-efficacy by building upon the client’s strengths and self-knowledge about what helps them change.

Research findings on Learning MI.

Extensive research has been conducted to explore how best to train providers in MI (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Madson, Loignon & Lane, 2009; de Roten et al., 2013; Barwick et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2012; Darnell et al., 2016; Mitcheson, Bhavsar & McCambridge, 2009). Studies have found that MI can be learned by providers regardless of professional experience or background and that following a standard 2-day workshop, attendees typically demonstrate an increase in MI skills (i.e., greater use of open-ended questions, greater empathy, etc.) which tend to diminish over the next 8–12 weeks without post-workshop feedback and coaching (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Madson, Loignon & Lane, 2009; Barwick et al., 2012). Individualized feedback (often using audio-recorded sessions) and coaching improve MI skills (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Miller et al., 2004). While workshops and follow-up coaching are shown to improve MI skills, these improvements are often insufficient to attain MI proficiency, which highlights a challenge to the dissemination and implementation of this evidence-based intervention (Carroll, Nich & Rounsaville, 1998; Smith et al., 2012; Darnell et al., 2016; Mitcheson, Bhavsar & McCambridge, 2009).

An outline of the Options sessions is provided in Table 2. Sessions were designed to be 20–30 minutes in duration and to be delivered by counselors with varying levels of formal counseling training (i.e., about half the counselors would be nurses, the other half formally trained counselors). A detailed counseling manual outlined a sequence of tasks for Enrollment, Follow-Up, End Visit sessions, including task goals, descriptions, and sample scripts. The manual, however, was not intended as a script for the session, since rigid adherence to a manual can impede the counseling relationship and even result in poorer outcomes (Hettema, Steele & Miller, 2005). In addition, a tabletop flipchart that followed the sequence of tasks presented in the manual and incorporated key client-centered and technical components of MI helped guide and support the counselors while facilitating a conversational tone during the sessions. The flipchart was translated into the local languages for each study site; the manual was only provided in English. In general, counseling sessions occurred in the language preferred by the participant. However, on a rare occasion, a participant’s preference for a specific counselor or limited staffing resulted in a session being conducted in English even if the participant appeared to be more comfortable speaking the local language.

Table 2.

Outline of Participant-Centered Adherence Counseling Sessions

| Enrollment Visit | ||

| 1. | Welcome participant to the session and affirm attendance. | |

| 2. | Provide overview of what will occur during counseling sessions. | |

| 3. | Clarify counselor’s role, emphasize respect for the participant’s choice about Dapivirine Vaginal Ring use and a collaborative, non-judgmental approach. | |

| 4. | Explore participant’s motivations for joining HOPE. | |

| 5. | Explore knowledge of ASPIRE results to ensure the participant is well informed before she makes any decisions about Dapivirine Vaginal Ring use. | |

| 6. | Inquire if participant is interested in using the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring and/or another HIV prevention method. | |

| 7. | Explore participant’s decision to use/not use the ring. Help participant develop a plan for using the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring consistently, if applicable. | |

| 8. | Explore participant’s decision to use other HIV prevention approaches. Help her to develop a plan for using them consistently, if applicable. | |

| 9. | Assess importance and confidence in implementing selected approaches in the participant’s life. | |

| 10. | Provide participant with an opportunity to share any remaining questions/concerns. | |

| 11. | Wrap-up by affirming attendance and giving a brief overview of the next visit. | |

| Follow-Up Visits: Months 1, 2, 3, 6, and 9 | ||

| 1. | Welcome participant, affirm attendance, normalize potential difficulties in implementing HIV prevention methods, provide brief overview of the session. | |

| 2. | Present information on what drug level results mean and how they pertain to protection against HIV (only if participant chose the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring). | |

| 3. | BEGINNING AT MONTH 3: Remind participant about purpose of sharing residual drug levels (only if participant chose the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring) to reduce defensiveness. | |

| 4. | BEGINNING AT MONTH 3: Share Ring drug level results to gauge the level of protection participant received from the Dapivirine Vaginal Ring. | |

| 5. | Explore how participant is doing with her HIV prevention plan, identifying barriers and facilitators to each of her selected methods. | |

| 6. | Assess how participant is feeling about her HIV prevention choices. Open a discussion about what she’d like to do with her plan going forward. | |

| 7. | Problem-solve ways to maintain or improve the participant’s HIV prevention plan that are in-line with the participant’s goals and desires. | |

| 8. | Assess and problem-solve any potential obstacles that might affect participant’s HIV prevention plan. | |

| 9. | Assess confidence in implementing HIV prevention plan consistently. | |

| 10. | Provide participant with an opportunity to share any remaining questions/concerns. | |

| 11. | Wrap-up by affirming attendance and giving a brief overview of the next visit. | |

| End Visit: Month 12 | ||

| 1. | Welcome participant, affirm attendance and commitment to finishing the study, and give a brief overview of the session. | |

| 2. | Review meaning of Drug Level results. | |

| 3. | Review purpose of sharing residual Drug Levels. | |

| 4. | Share Dapivirine Vaginal Ring Drug Level results. | |

| 5. | Explore how participant is doing with her HIV prevention plan to inform future plans. Identify barriers and facilitators to each method and prompt her to think about how she could overcome similar obstacles going forward. | |

| 6. | Develop an HIV prevention plan for the future, keeping in mind what has worked best for the participant throughout the HOPE study. | |

| 7. | Assess confidence in remaining HIV negative. | |

| 8. | Provide participant with an opportunity to share any remaining questions/concerns. | |

| 9. | Acknowledge and affirm participant’s contribution to the study. Express gratitude for her continued commitment and openness. | |

Training of Counselors

Existing counseling and nursing staff at the study sites were designated by site leadership to be counselors for this study. All counselors were fluent in English and most also spoke the local languages. All training was conducted in English.

Training Materials

Prior to in-person training, counselors received the counseling manual, the desktop flipchart, and access to training videos posted on YouTube of mock counseling sessions that depicted different study visits and approaches to facilitating residual drug level discussions with participants.

In-person Training

Counselors completed an initial two days of in-person training on delivering the intervention. One year later they completed an additional two days of booster training focused on the Product Use End Visit and other issues relevant to sessions occurring towards the end of study follow-up (i.e., sustaining participant engagement, delivering briefer sessions that met fidelity criteria). The first author (IB) conducted all in-person trainings in a central location with counselors from all study sites. Trainings included didactic teaching and experiential exercises designed to foster client-centered concepts and improve basic counseling skills. Following a review of Options, the counselors role-played counseling sessions with peers and were provided with feedback.

Mock Sessions

After the in-person training, counselors conducted three audio-recorded mock sessions with a peer using a standard client scenario. Sessions had to meet pre-established fidelity criteria (described below), otherwise the counselor received additional coaching and had to redo the session. Once three mock sessions met fidelity criteria, the counselor was certified to conduct Options with participants. At least one counselor at the study site had to be certified to conduct Options prior to site activation.

New Counselors

New counselors were trained by certified counselors at the study site and had to submit three mock sessions that passed fidelity criteria before seeing study participants.

Coaching Sessions

Monthly coaching sessions were conducted with small groups of counselors across study sites. Because individual counselors received feedback through their rating forms, coaching sessions addressed counseling components where the ratings showed consistent difficulties. During these sessions, counselors also discussed situations for which they needed further guidance. Lastly, these calls were used to disseminate updates to the counseling processes and to share experiences across sites. Although not a requirement, approximately half the sites also instituted weekly or bimonthly counselor’s meetings for peer coaching.

Fidelity Monitoring and Feedback

Counseling Ratings Form

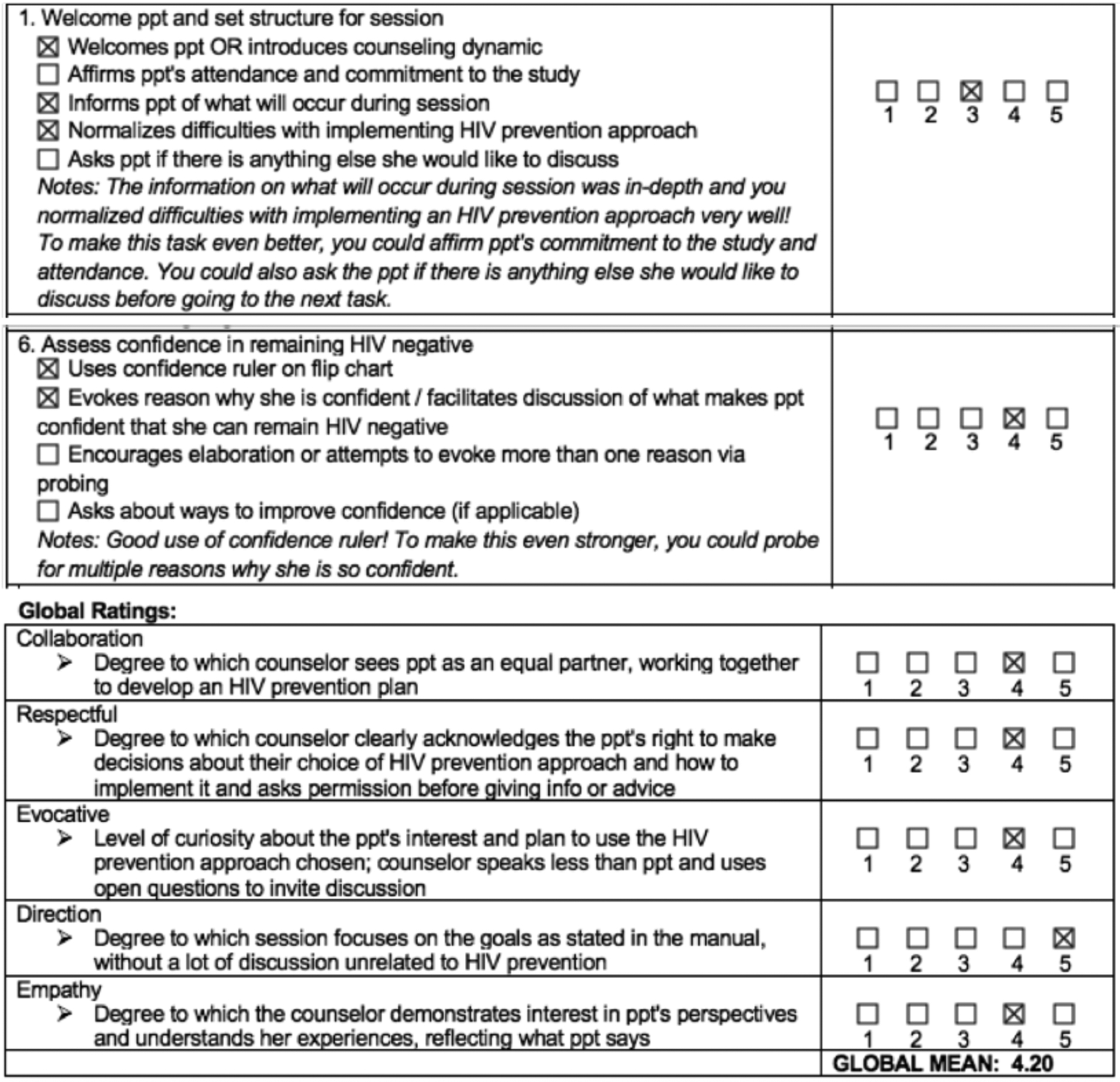

Each session was rated according to two components: Session tasks and the client-centeredness of the interaction. As shown in Figure 1, the fidelity ratings form presented each session task, as outlined in the counseling manual, with tick boxes that indicated key components that were to be covered during each task. This facilitated consistent feedback to counselors; if a box was left unchecked, a counselor could see that they missed that component. Each task was rated 1 to 5, where 1 indicated the task was skipped, 2 or 3 that key components were missed, 4 that all components were covered (i.e., material in the flipchart was covered), and 5 that the task was completed at a level equivalent to or better than the manual. The client-centered ratings, which also ranged from 1 to 5, were derived from the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding system (MITI v3.1.1) (Moyers et al., 2010), and included individual ratings and descriptions for Collaboration, Respect for Autonomy, Evocation, Direction, and Empathy. Space was also allotted for the rater to provide qualitative feedback to the counselor.

Figure 1.

Participant Centered Counseling Rating Form(Excerpt)

The Rating Team

Study raters were hired by October 2016, after the rating materials had been developed and finalized. Raters for sessions in Xhosa, Zulu, Luganda, Chichewa, and Shona were all bilingual and bicultural immigrants from those study countries currently living in the New York metropolitan area. Other study staff rated the English language sessions.

Interrater Reliability (IRR)

Raters underwent two initial training sessions; the first provided an overview of client-centered counseling in general, and the second covered the HOPE study counseling objectives and the fidelity ratings guide. Afterwards, they rated two Enrollment sessions together in English, stopping the audio recording to discuss the rating for each task before moving on to the next. Subsequently, they rated three Enrollment sessions independently, meeting afterwards to discuss their ratings and reach concordance. Once interrater reliability was established for the Enrollment sessions, similar trainings were conducted for Follow-up and Product Use End Visit sessions. To facilitate IRR, a ratings guide was developed that provided greater detail about each task and gave examples of tasks completed at levels of 1 through 5.

Rater training was considered complete when 80% of the ratings for individual tasks and client-centered subscales on an assigned session matched the mode and 100% were within 1 of the mode. Monthly IRR assessments began in February 2017 to ensure that raters remained calibrated as a rating unit. After independently rating two English-language sessions, the rating team met to discuss and clarify ratings discrepancies, challenges, and best practices for providing client-centered feedback to study counselors. Between February 2017 and May 2018, 32 sessions (seven Enrollment=7, Follow-up=19, End=6) were rated to determine IRR. During that period, a median of 71.7% (range= 58%−90% across months) of ratings matched the mode and 96.7% (range =79% to 100%) were within 1 of the mode.

Session Recording and Uploading

All Options sessions were to be audio-recorded and uploaded to a secure server. All sessions were to follow the standard format, regardless of whether it was being recorded. Each uploaded session was then logged in a spreadsheet. Session ratings were later added to this spreadsheet for sessions that were reviewed. The first five sessions for each counselor were reviewed; if these were all Enrollment Visit sessions, then the first three Follow-up Visit sessions were also reviewed. Subsequently, once a counselor had uploaded ten sessions, one was randomly selected for review. To ensure that each counselor received feedback regularly, at least two randomly selected sessions were rated for each counselor per month. After a session was reviewed, the completed rating form was emailed to the counselor to provide her/him with feedback. Ratings forms were not sent to site leadership, although they were informed if a counselor or group of counselors were consistently performing poorly to establish a plan to improve fidelity.

Results

Session Recording and Uploading

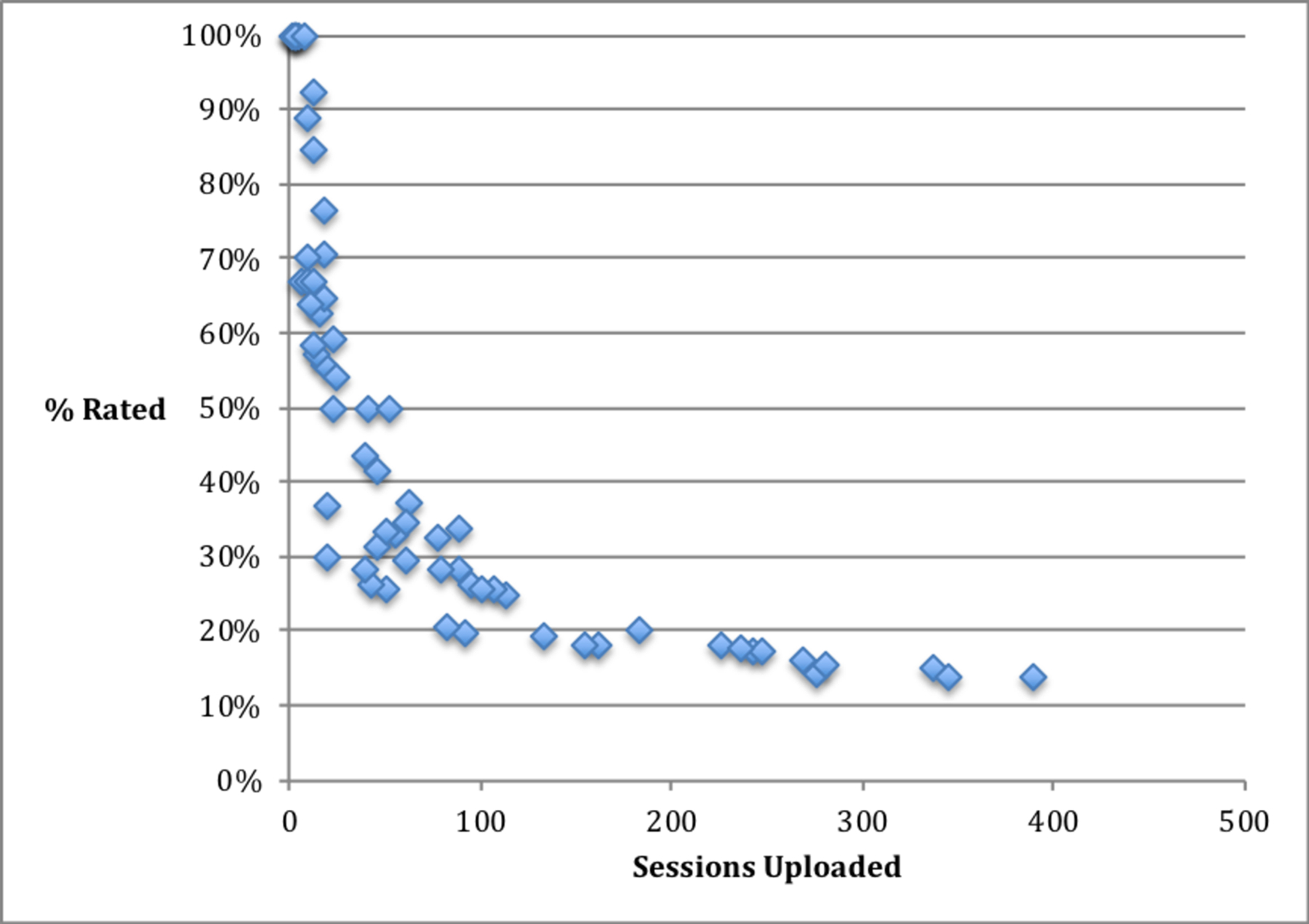

Among the 1,456 participants enrolled in the study, 85.7% (range= 49.4% - 100.0% across sites) allowed at least one of their sessions to be audio-recorded; 20% of participants gave consent for all counseling sessions to be recorded. There were 9,926 study visits in which an Options counseling session was expected to occur, with no reported incidences of an Options session being omitted during a scheduled study visit. Of these, 5,366 (54.1%; range=8.1% - 95.9% across sites) sessions were audio-recorded and uploaded to the server for review. Most often, lack of session recordings was due to participants declining to be recorded. Among the 63 counselors who delivered sessions, the median number of sessions uploaded per counselor was 46 (range=1 – 389); nine counselors uploaded fewer than 10 recordings. Consistent with expectations, the median duration of Enrollment Visit counseling sessions was approximately 28 minutes (N= 260; Range= 8:33 – 63:55), while those of the Follow-up and End visits were both 16 minutes (N= 770; Range= 4:11 – 66:53 and N= 208; Range= 4:55 – 40:12, respectively).

Overall Fidelity

Of the 5,366 sessions recorded, 1,238 (23.07%) were reviewed for fidelity. Of these, 775 (62.6%; range=26.67% - 97.97% across sites) were rated as good (session tasks and client-centered mean ratings were ≥4), 264 (21.3%; range=2.03% - 36.43%) were rated as fair (mean ratings for either or both components were between 3.5 and 4), and 199 (16.1%; range=0.00% - 46.67%) as poor (mean ratings for at least one component were below 3.5). Across all sessions, the median session task and client-centeredness average ratings were 4.30 (range=2.13 – 5.00) and 4.25 (range= 1.25–5.0), respectively. Across study sites, eleven counselors who failed to consistently deliver the intervention were replaced by other certified counselors at the site or newly hired counselors and reassigned to back-up status.

Feedback to Counselors

The median number of days that elapsed between the upload and review of a given session was 9 (range 0–88 days), whereas the median for individual study sites ranged from 6 to 13 days. Factors affecting session review time included: surges in the number of sessions uploaded, whether due to heavy participant volume or site delays in uploading recorded sessions; how long it took a counselor to upload 10 sessions so one could be randomly selected for review; and whether the session was conducted in English (which could be rated by numerous raters) or a local language (which could only be rated by a single rater, who might be temporarily unavailable).

Figure 2 displays the distribution of rated sessions based on the number of sessions uploaded by counselors. As expected due to the pre-established frequency of rating sessions, counselors who uploaded few sessions had almost all of them reviewed, whereas the proportion of sessions reviewed for those who completed at least 100 sessions stabilized in the 14 – 25 percent range.

Figure 2.

Percent of uploaded sessions rated by counselor.

Discussion

The emergence of PrEP has changed the landscape of HIV prevention. However, poor adherence has also highlighted the need for adjunctive evidence-based adherence counseling interventions. This study demonstrates the feasibility and success of implementing a fidelity monitoring process using audio-recording and rating of counseling sessions in a multi-site, multi-language, multi-country PrEP trial to ensure consistent quality of adherence counseling sessions. Achieving 83.9% of sessions with “fair” or “good” ratings is particularly noteworthy in a large-scale study in which, as is typical in PrEP, the counseling was conducted by existing staff whose prior formal training in counseling varied. These findings suggest that with regular and consistent monitoring and feedback, even counselors with limited experience in delivering evidence-based counseling approaches can attain fair fidelity even with complex MI-based interventions.

While session monitoring can be perceived as a harsh oversight, published studies have reported that when paired with supportive ongoing skills training and coaching, this process is well-received by counselors and can improve the retention of counseling staff, who view the process as contributing to their skills development (Aarons et al., 2009). As such, this process may be particularly useful in building capacity in the resource-limited settings where HIV prevention research is most commonly conducted. Session monitoring can also identify counselors who are performing poorly, which is invaluable, as such counselors often overestimate their competence significantly more on self-ratings of fidelity than well-performing counselors (Brosan, Reynolds & Moore, 2008). In this study, fidelity monitoring helped identify poorly performing counselors who were then given further training (including additional in-person training) and, on some occasions, replaced and re-assigned to back-up status to ensure that study participants received optimal counseling from more skilled staff members.

Although findings from this study demonstrate the feasibility of counseling fidelity monitoring in PrEP studies, it is important to note that the content of the fidelity monitoring may vary depending on the needs of the study. For example, research has shown that learning MI, a nuanced counseling approach that encompasses both relational and technical aspects, can be difficult (Madson, Loignon & Lane, 2009; deRoten et al., 2013; Barwick et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2012; Darnell et al., 2016; Mitcheson, Bhavsar & McCambridge, 2009). Training and monitoring programs for simpler interventions that are easier to learn and master may be less intensive, but equally important in order to prevent drift back to the counselor’s typical counseling style.

This study did find significant variability across sites with regards to the ability to record sessions. Thus, it is possible that at sites with fewer session recordings counselors may not have received sufficient feedback to maintain or improve their delivery of Options. While this study did not systematically explore challenges to audio-recording, participant or counselor discomfort, participants’ misunderstanding of the purpose of the recordings, and/or distrust in the relationship between participants and the study site could have all been contributors.

Conclusions

Maximizing the effectiveness of PrEP will require an integration of biomedical and behavioral science. This study demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of fidelity monitoring to ensure that the adherence counseling being provided to study participants consistently meets quality standards. The cost of including fidelity monitoring in this study was modest, accounting for approximately 2.8% of the total budget. Given the investment necessary to conduct large HIV prevention trials, our findings demonstrate that integration of similar fidelity monitoring in future PrEP trials with an adherence counseling component is highly warranted.

Acknowledgments:

The authors wish to thank the entire HOPE study team, especially the HOPE study counselors and participants. This study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN), funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through individual grants (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615 and UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). The HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health through a center grant (P30-MH43520, PI: Remien). The vaginal rings used in this study were developed and supplied by the International Partnership for Microbicides (IPM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Aarons GA, Sommerfeld DH, Hecht DB, Silovsky JF, & Chaffin MJ (2009). The impact of evidence-based practice implementation and fidelity monitoring on staff turnover: evidence for a protective effect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(2), 270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR, Mansoor LE, Corneli A, Torjesen K, & van der Straten A (2013). Adherence support approaches in biomedical HIV prevention trials: experiences, insights and future directions from four multisite prevention trials. AIDS and Behavior, 17(6), 2143–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR, McMahan V, Goicochea P, Vargas L, Marcus JL, Grant RM, & Liu A (2012). Supporting study product use and accuracy in self-report in the iPrEx study: next step counseling and neutral assessment. AIDS and Behavior, 16(5), 1243–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, & Longabaugh R (2009). Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: a review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction, 104(5), 705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS, Ball SA, Campbell BK, Miele GM, Schoener EP, & Tracy K (2007). Training and fidelity monitoring of behavioral interventions in multi-site addictions research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87(2–3), 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeten JM, Palanee-Phillips T, Brown ER, Schwartz K, Soto-Torres LE, Govender V, … & Siva S. (2016). Use of a vaginal ring containing dapivirine for HIV-1 prevention in women. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(22), 2121–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balán I, Carballo-Diéguez A, Giguere R, Lama J, & Cranston R (2014). Implementation of an Adherence Counseling Intervention in a Microbicide Trial: Challenges in Changing Counselor Behavior. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(S1), A255–A255. [Google Scholar]

- Barwick MA, Bennett LM, Johnson SN, McGowan J, & Moore JE (2012). Training health and mental health professionals in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(9), 1786–1795. [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, … & Czajkowski S. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosan L, Reynolds S, & Moore RG (2008). Self-evaluation of cognitive therapy performance: do therapists know how competent they are? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(5), 581–587. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BK, Buti A, Fussell HE, Srikanth P, McCarty D, & Guydish JR (2013). Therapist predictors of treatment delivery fidelity in a community-based trial of 12-step facilitation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 39(5), 304–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K, Nich C, & Rounsaville B (1998). Utility of therapist session checklists to monitor delivery of coping skills treatment for cocaine abusers. Psychotherapy Research, 8(3), 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, Taylor D, Ahmed K, Agot K, … & Van Damme L. (2014). FEM-PrEP: adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66(3), 324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell D, Dunn C, Atkins D, Ingraham L, & Zatzick D (2016). A randomized evaluation of motivational interviewing training for mandated implementation of alcohol screening and brief intervention in trauma centers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 60, 36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roten Y, Zimmermann G, Ortega D, & Despland JN (2013). Meta-analysis of the effects of MI training on clinicians’ behavior. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(2), 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing RE, El-Bassel N, Ghesquiere A, Baldwin S, Gillies J, & Ngeow E (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, … & Montoya-Herrera O. (2010). Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2587–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, & Miller WR (2005). Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psycholology, 1, 91–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Lichvar E, Bobek M, & Henderson CE (2015). Validity of therapist self-report ratings of fidelity to evidence-based practices for adolescent behavior problems: Correspondence between therapists and observers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(2), 229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Garland AF, Nguyen K, & Brookman-Frazee L (2010). Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevany S, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Singh B, Chingono A, Morin S, & NIMH Project Accept Study Team. (2016). Global Health Diplomacy, Monitoring & Evaluation, and the Importance of Quality Assurance & Control: Findings from NIMH Project Accept (HPTN 043): A Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial of Community Mobilization, Mobile Testing, Same-Day Results, and Post-Test Support for HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa and Thailand. PloS One, 11(2), e0149335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SS, Ali D, Kennedy A, Tesfaye R, Tadesse AW, Abrha TH, … & Menon P. (2015). Assessing implementation fidelity of a community-based infant and young child feeding intervention in Ethiopia identifies delivery challenges that limit reach to communities: a mixed-method process evaluation study. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Glidden DV, Anderson PL, Amico KR, McMahan V, Mehrotra M, … Grant R. (2014). Patterns and correlates of PrEP drug detection among MSM and transgender women in the Global iPrEx Study. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 67(5):528–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madson MB, Loignon AC, & Lane C (2009). Training in motivational interviewing: A systematic review. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(1), 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, & Apodaca T (2009). The Route To Change: Within-session Predictors Of Change Plan Completion In A Motivational Interview: 405. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research, 33, 112A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, & Longabaugh R (2014). The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI’s key causal model. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 82(6), 973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, Gomez K, Mgodi N, Nair G, … Chirenje ZM. (2015). Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(6), 509–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, & Carroll KM (2009). Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychotherapy Research, 19(2), 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, & Barlow DH (2010). The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: a review of current efforts. American Psychologist, 65(2), 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2012). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, & Pirritano M (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitcheson L, Bhavsar K, & McCambridge J (2009). Randomized trial of training and supervision in motivational interviewing with adolescent drug treatment practitioners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37(1), 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Manuel JK, Wilson PG, Hendrickson SM, Talcott W, & Durand P (2008). A randomized trial investigating training in motivational interviewing for behavioral health providers. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, & Martin T (2006). Therapist influence on client language during motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of substance abuse treatment, 30(3), 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, & Tonigan JS (2009). From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: a causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1113–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, & Ernst D (2010). Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1. 1 (MITI 3.1. 1). Albuquerque, NM: Center on Alcoholism. Substance Abuse and Addictions. [Google Scholar]

- Nishita C, Cardazone G, Uehara DL, & Tom T (2013). Empowered diabetes management: life coaching and pharmacist counseling for employed adults with diabetes. Health Education & Behavior, 40(5), 581–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Mayer KH, Ou SS, McCauley M, Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, … & Chen YQ. (2015). Adherence to early antiretroviral therapy: results from HPTN 052, a phase III, multinational randomized trial of ART to prevent HIV-1 sexual transmission in serodiscordant couples. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 69(2), 234–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalbe CS, Oh HY, & Zweben A (2014). Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta‐analysis of training studies. Addiction, 109(8), 1287–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Carpenter KM, Amrhein PC, Brooks AC, Levin D, Schreiber EA, … & Nunes EV. (2012). Training substance abuse clinicians in motivational interviewing using live supervision via teleconferencing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(3), 450–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader AM, Walters ST, Prabhu GC, Houck JM, & Field CA (2010). The language of motivational interviewing and feedback: counselor language, client language, and client drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 190–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox S, Parra-Medina D, Felton GM, Poston MB, & McClain A (2010). Adoption and implementation of physical activity and dietary counseling by community health center providers and nurses. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 7(5), 602–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]