Healthcare-associated respiratory viral infections (RVI) remain an underappreciated cause of in-hospital morbidity and mortality [1]. Infection prevention bundles comprising segregation of symptomatic patients, droplet/contact precautions and visitor screening can potentially reduce the transmission of RVI on high-risk units [2], though hospital-wide implementation has been limited. The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic highlights the importance of strengthening hospital-wide infection control against common RVI. However, the effectiveness of infection control during a COVID-19 outbreak on healthcare-associated RVI has yet to be assessed.

In Singapore, a South-East Asian city-state, local transmission of COVID-19 has been ongoing since February 2020. While various public health measures, such as suspension of mass gatherings, have been associated with a decrease in influenza-like activity in the community [3], the impact of intrahospital infection control measures on healthcare-associated RVI has not been assessed. At our institution, the largest tertiary-care hospital in Singapore (1700 beds), most patients were nursed in open-plan cohorted general wards. From February 2020, a bundle of infection prevention measures was sequentially introduced to reduce the risk of healthcare-associated transmission of COVID-19, including universal mask wearing, improved segregation of patients with respiratory symptoms, visitor screening and using appropriate personal protective equipment [4].

Waiver of informed consent was obtained for use of deidentified surveillance data (CIRB 2020/2436). The impact of these policies on the incidence of healthcare-associated RVI was evaluated by comparing the daily incidence of healthcare-associated RVI among hospitalized inpatients over the 4 months before the COVID-19 outbreak (October 2019 to January 2020) with the incidence of healthcare-associated RVI over the following 3 months (February to April 2020) during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also compared the number of healthcare-associated RVI (excluding severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)) over a 7-year period, from 2015 to 2020, by epidemiologic week (E-week). PCR-positive cases of RVI were categorized as healthcare associated if the RVI was identified beyond the maximum incubation period since the time of admission [2]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, all inpatients admitted with concurrent respiratory symptoms, as well as those fulfilling suspect case criteria for COVID-19, were tested for SARS-CoV-2 along with a panel of 16 other common RVIs (influenza A/B, human parainfluenza virus 1/2/3/4, respiratory syncytial virus subtypes A/B, human metapneumovirus, human coronavirus (229E/NL63/OC43), rhinovirus A/B/C, enterovirus, adenovirus and human bocavirus 1/2/3/4) [4]. Over the study period, there was no change in the indications for RVI testing, and we observed no substantial decrease in the number of admissions with community-onset RVI at our institution [5].

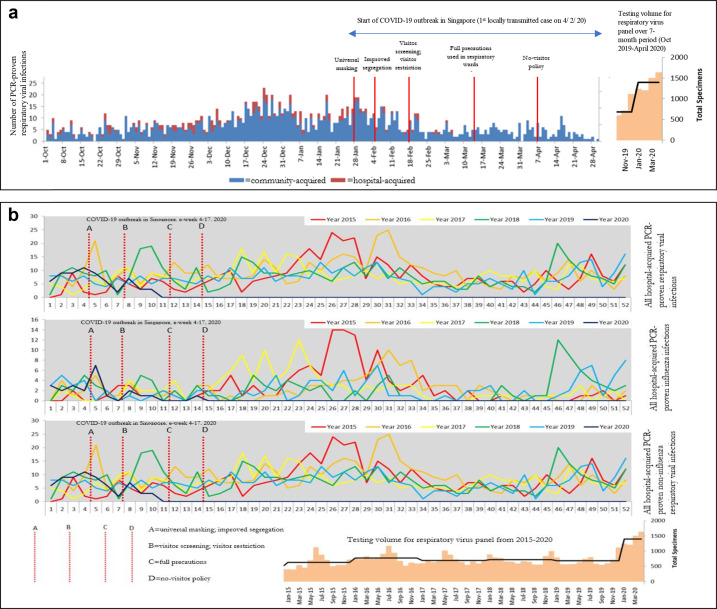

Before the COVID-19 outbreak (1 October 2019 to 28 January 2020), the cumulative incidence of PCR-proven healthcare-associated RVI was 5.60 cases per 1000 admissions, and 9.25 cases per 10 000 patient-days (153 cases; 27 322 admissions, 165 461 patient-days), which is comparable to rates reported elsewhere [2]. During sequential introduction of the infection control bundle, from 29 January 2020 to 30 April 2020, the cumulative incidence of PCR-proven, healthcare-associated RVI was 1.64 cases per 1000 admissions, and 2.54 cases per 10 000 patient-days (27 cases; 16 445 admissions, 106 259 patient-days). The incidence rate ratio of PCR-proven healthcare-associated RVI per 1000 admissions was 0.29 (95% confidence interval, 0.19–0.44; p < 0.001). The marked decrease in healthcare-associated RVI was observed despite increased RVI testing volume (Fig. 1 (a)).

Fig. 1.

Trend of healthcare-associated RVI at a tertiary-care hospital in Singapore over a 7-month period (October 2019 to April 2020) and by epidemiologic week from 2005 to 2020, after sequential implementation of infection control measures during a COVID-19 outbreak. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; RVI, respiratory viral infection. a) Trend of common respiratory viral infections (excluding SARS-CoV-2) at a tertiary hospital in Singapore, after sequential implementation of infection control measures during a COVID-19 outbreak. b) Trend of hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections (excluding SARS-CoV-2) at a tertiary hospital in Singapore, by epidemiological-week, and testing volumes for respiratory virus panel from 2015–2020.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, four sets of infection control measures were introduced. From E-week 5–6, a universal policy mandating that all healthcare workers wear masks in clinical areas was introduced, and patients with respiratory symptoms but no epidemiologic risk for COVID-19 were segregated in designated clinical areas (respiratory surveillance wards, RSWs). In RSWs, the distance between beds was increased, social distancing was encouraged and wearing surgical masks among inpatients was mandatory, with healthcare workers wearing N95 respirators [4]. Subsequently, from E-week 8, temperature screening for visitors and visitor restrictions were introduced (one visitor per patient at any time, with visitors with fever denied entry). From E-week 12, personal protective equipment used in the RSWs was upgraded to full precautions (N95 respirators, face shields, gowns and gloves). Finally, at E-week 15, a hospital-wide no-visitor policy was enforced. After sequential introduction of universal mask wearing, improved segregation of symptomatic patients and visitor screening, the number of healthcare-associated RVI fell to zero and remained flat over the subsequent 2 months—an observation not previously replicated in the preceding 5 years of surveillance (Fig. 1(b)). This was before use of full personal protective equipment in RSWs and the introduction of a no-visitor policy. Over the same time period, a total of 677 COVID-19 cases were managed in our institution. Despite extensive surveillance, there was only one potential instance of patient-to-patient transmission of COVID-19, and no evidence of transmission from patient to healthcare worker [4].

Implementation of universal mask wearing, strict patient segregation and visitor screening was not just effective in containing COVID-19 [4], but also resulted in an unprecedented and sustained hospital-wide decrease in healthcare-associated RVI. Given that common RVI still account for a substantial proportion of in-hospital morbidity and mortality [5], infection prevention measures can mitigate healthcare-associated RVI and should continue in some form even after the COVID-19 pandemic is over.

Transparency declaration

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Editor: L Leibovici

References

- 1.Chow E.J., Mermel L.A. Hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections: incidence, morbidity, and mortality in pediatric and adult patients. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx006. :ofx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mermel L.A., Jefferson J.A., Smit M.A., Auld D.B. Prevention of hospital-acquired respiratory viral infections: assessment of a multimodal intervention program. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019;40:362–364. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soo R.J.J., Chiew C.J., Ma S., Pung R., Lee V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wee L.E., Sim X.Y.J., Conceicao E.P., Aung M.K., Tan K.Y., Ko K.K.K., et al. Containing COVID-19 outside the isolation ward: the impact of an infection control bundle on environmental contamination and transmission in a cohorted general ward. Am J Infect Control. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.06.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wee L.E., Ko K.K.K., Ho W.Q., Kwek G.T.C., Tan T.T., Wijaya L. Community-acquired viral respiratory infections amongst hospitalized inpatients during a COVID-19 outbreak in Singapore: co-infection and clinical outcomes. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104436. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]