Abstract

A range of studies showed probiotics like Streptococcus oligofermentans and Limosilactobacillus reuteri to inhibit the cariogenic activity and survival of Streptococcus mutans, possibly via the production of substances like H2O2, reuterin, ammonia and organic acids. We aimed to assess the environment-specific mechanisms underlying this inhibition. We cultured L. reuteri and S. oligofermentans in various environments; minimal medium (MM), MM containing glucose (MM+Glu), glycerol (MM+Gly), lactic acid (MM+Lac), arginine (MM+Arg) and all four substances (MM+all) in vitro. Culture supernatants were obtained and metabolite concentrations (reuterin, ammonia, H2O2, lactate) measured. S. mutans was similarly cultivated in the above six different MM variation media, with glucose being additionally added to the MM+Gly, MM+Lac, and MM+Arg group, with (test groups) and without (control groups) the addition of the supernatants of the described probiotic cultures. Lactate production by S. mutans was measured and its survival (as colony-forming-units/mL) assessed. L. reuteri environment-specifically produced reuterin, H2O2, ammonia and lactate, as did S. oligofermentans. When cultured in S. oligofermentans supernatants, lactate production by S. mutans was significantly reduced (p < 0.01), especially in MM+Lac+Glu and MM+all, with no detectable lactate production at all (controls means ± SD: 4.46 ± 0.41 mM and 6.00 ± 0.29 mM, respectively, p < 0.001). A similar reduction in lactate production was found when S. mutans was cultured in L. reuteri supernatants (p < 0.05) for all groups except MM+Lac+Glu. Survival of S. mutans cultured in S. oligofermentans supernatants in MM+Lac+Glu and MM+all was significantly reduced by 0.6-log10 and 0.5-log10, respectively. Treatment with the supernatant of L. reuteri resulted in a reduction in the viability of S. mutans in MM+Gly+Glu and MM+all by 6.1-log10 and 7.1-log10, respectively. Probiotic effects on the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans were environment-specific through different pathways.

Keywords: caries, colony forming units, dental, lactate production, metabolites, probiotics

Introduction

The human oral cavity harbors more than 700 microbial species, which constitute a dynamic microbial community (Aas et al., 2005). The coexistence and competition between different species are central to the oral microbial homeostasis (Bao et al., 2015). A disturbance in this homeostasis, termed dysbiosis, is associated with dental diseases like dental caries or periodontitis (Exterkate et al., 2010). For dental caries, the dominance of acidogenic and aciduric species like Streptococcus mutans, triggered by the abundant intake of fermentable carbohydrates, is associated with a net mineral loss from dental hard tissues and the formation of a caries lesion (Marsh, 2006).

Contemporary caries management aims to rebuild a healthy microbial equilibrium within the dental biofilm (Marsh, 2006; Bao et al., 2015). One strategy supposedly supporting such rebalancing of the biofilm is the application of probiotics. Probiotics are microorganisms, mainly bacteria, that when administered in sufficient amounts, provide health benefits to the host (Ng et al., 2009; Bosch et al., 2012), for example by inhibiting the metabolic activity and survival of harmful microbiota as well as modulating the host’s immune response, thereby helping to stabilize the local microecosystem (Meurman, 2005). Probiotics have been tested both in vitro and in clinical studies for their anti-caries effect, with mixed results (Jalasvuori et al., 2012; Gruner et al., 2016).

Certain probiotics have been tested more widely. Streptococcus oligofermentans, a synonym of Streptococcus cristatus (Jensen et al., 2016) was isolated from healthy tooth surfaces (Tong, 2003) and has anti-bacterial effects against pathogens like S. mutans (Liu et al., 2014). It produces hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) from lactic acid (Tong et al., 2007, 2008) as well as ammonia from arginine, which may both reduce the amount of free lactic acid, thereby increasing the local pH and preventing the initiation of a caries lesion or slowing down or stopping lesion progression (Burne and Marquis, 2000; Clancy et al., 2000). Limosilactobacillus reuteri (Zheng et al., 2020) is an obligate heterofermentative probiotic and most strains in its human lineages have the ability to excrete reuterin (Mu et al., 2018), a potent antibiotic substance, which exhibits broad-spectrum antimicrobial effect on Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (Talarico and Dobrogosz, 1989; Doleyres et al., 2005). In addition to reuterin, L. reuteri also produces H2O2, organic acid (Kang et al., 2011) and ammonia (Mu et al., 2018; Zaura and Twetman, 2019), with possible impact on S. mutans metabolic activity and survival. Furthermore, some strains of L. reuteri generate a unique antagonistic activity, reutericyclin, which shows a broad inhibitory spectrum but has no effect on the growth of gram-negative bacteria (Ganzle et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2015).

The antibacterial effect of these probiotics hence relies, at least in parts, on the production of the described substances. This production, in turn, is likely to be dependent on the environmental conditions, especially the availability of certain educts required to produce reuterin, H2O2 etc., So far, it was not studied if different environments modify the probiotic effects on cariogenic pathogens like S. mutans. Deeper knowledge on such environmental requirements is needed both for future research (setting up appropriate models considering these requirements) and for clinical applications. For example, it may be feasible to boost the probiotic anti-caries effect by supplementing probiotic products with certain substances required for a specific probiotic activity.

We aimed to assess the environment-specific activity and impact of two different probiotics, S. oligofermentans, and L. reuteri, on the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans. We hypothesized that the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans is significantly reduced when exposed to probiotic supernatants, and that this effect is environment-specific.

Materials and Methods

This study used an established in vitro model (Ganas and Schwendicke, 2019) to assess the environment-specific impact of probiotics on metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans. Different environmental conditions were simulated by using determined modifications of a saliva analog, allowing to deterministically vary the metabolic activity of the two different probiotics, S. oligofermentans, and L. reuteri. The supernatants resulting from the cultivation of probiotics in different environments were then used to assess their impact on S. mutans metabolic activity, measured via determining the lactate production, and survival, measured via the colony-forming-units/mL of S. mutans. Controls of S. mutans cultured in different environments, but without probiotic supernatant, were additionally used. All assays and tests were performed in three biological replications, each with two technical replications (measurements) whose average was used for statistical analysis.

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

Three bacterial strains S. mutans, DSM 20523, S. oligofermentans, DSM 8249 (DMSZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and L. reuteri, ATCC PTA 5289 (BioGaia, Stockholm, Sweden) were used. The strains S. mutans and S. oligofermentans were grown on blood agar plates COLS+ (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) while the strain L. reuteri was maintained on deMan-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) agar (Oxoid) at 37°C aerobically for 1–2 days.

Preparation of Deproteinized Supernatants From Probiotics Cultures

The two probiotics were precultured separately in brain-heart-infusion (BHI) broth (Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 1% glucose (Carl Roth), 4 g/L yeast extract and 8 g/L beef extract (Carl Roth) for 18 h under aerobic conditions at 37°C in 15 ml Falcon tubes (Corning, Kaiserslautern, Germany). After centrifugation at 7100 g for 15 min at room temperature, the supernatants were removed and the cells were transferred to 0.9% sodium chloride with an inoculum (means ± SD) of 3.96 ± 0.37 × 107 cells/mL for S. oligofermentans and 4.16 ± 0.22 × 107 cells/mL for L. reuteri, with a total of 6 ml-cultures in 15 ml Falcon tubes (Corning), respectively. After another centrifugation at 7100 g for 15 min, the supernatants were discarded and 6 mL Minimal Medium (MM) was added.

The minimal medium was based on a chemically defined saliva analog (Wong and Sissions, 2001) and consisted of 10 mM KH2PO4 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), 10 mM K2HPO4 (Carl Roth), 1 mM NaCl (Carl Roth), 3 mM KCl (Merck), 0.2 mM NH4Cl (Merck), and 0.2 mM MgCl2 × 6H2O (Merck). The MM was supplemented as follows to generate six different MM variations, allowing to assess the relevance of the metabolic environment on the probiotic activity and its association with the inhibition of S. mutans survival and activity: (1) MM, (2) MM with 5 mM glucose (Carl Roth) (MM+Glu), (3) MM with 300 mM glycerol (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) (MM+Gly), (4) MM with 5 mM Lactic acid (Carl Roth) (MM+Lac), (5) MM with 5 mM arginine (Sigma-Aldrich) (MM+Arg) and (6) MM with 5 mM glucose, 300 mM glycerol, 5 mM Lactic acid and 5 mM arginine (MM+all). The final pH of the six MM variations was MM 6.95, MM+Glu 6.90, MM+Gly 6.92, MM+Lac 6.61, MM+Arg 7.14, MM+all 6.83. For the culture of S. mutans, in order to enable it to produce lactate, glucose was added to MM+Gly, MM+Lac, MM+Arg group to a final concentration of 5 mM.

In a pre-experiment, the cultivation period of the probiotics was varied (15 min, 30 min, 2, 4, and 18 h) to gauge the impact of this period on the production of H2O2, lactate, reuterin and ammonia. Different probiotic cultivation periods were eventually used to generate supernatants optimally enriched with these metabolites. As a consequence, S. oligofermentans, was cultured in MM+Glu and MM+Lac aerobically at 37°C for 30 min, in MM and MM+Gly for 2 h, and in MM+Arg and MM+all for 4 h, followed by centrifugation at 20800 g for 10 min at room temperature to obtain the supernatants. L. reuteri was cultured in MM+Glu, MM+Gly, MM+Lac and MM+all for 4 h and in MM and MM+Arg for 18 h, followed by the same protocol to collect supernatants. Deproteinization was conducted using Amicon Ultra-2ml centrifugal filter units with molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 10 kDa (Merck) at 7500 g for 20 min at room temperature. The deproteinized supernatants were maintained at −80°C for later processing. Control samples without bacteria were established using BHI medium containing 1% Glucose, 4 g/L yeast extract and 8 g/L beef extract followed by six different MM variations treated in the same way as in the bacterial culture groups.

Preparation of Deproteinized Supernatants From S. mutans Cultures

S. mutans was precultured in the BHI+1% glucose+4 g/L yeast extract+8 g/L beef extract medium for 18 h aerobically at 37°C in 15 mL Falcon tubes. After centrifugation at 7100 g for 15 min at room temperature, cultivation supernatants were removed. Cells were rinsed with 0.9% sodium chloride and after another centrifugation at 7100 g for 15 min, bacteria were transferred to MM, MM+Glu, MM+Gly+Glu, MM+Lac+Glu, MM+Arg+Glu and MM+all media, inoculated with 4.35 ± 0.39 × 107 cells as 1 mL-cultures in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), followed by incubation at 37°C aerobically for further 18 h. Control samples without bacteria were established using BHI medium containing 1% Glucose, 4 g/L yeast extract and 8 g/L beef extract followed by six different MM variations treated in the same way as in the bacterial culture groups, except that 5 mM glucose was additionally added to MM+Gly, MM+Lac, MM+Arg groups. Afterward, the deproteinized supernatants were collected and stored as described above.

Culture of S. mutans With Probiotic Supernatants

After pre-incubation in BHI+1% glucose+4 g/L yeast extract+8 g/L beef extract medium for 18 h, S. mutans was treated in the same manner as above with an inoculum of 4.29 ± 0.65 × 107 cells/mL. After centrifugation, the supernatants were discarded and 1 mL of the supernatants of S. oligofermentans and L. reuteri (cultured in the different MM as described) were pipetted into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes (Eppendorf). Glucose was additionally added to the MM+Gly, MM+Lac, and MM+Arg at a final concentration of 5 mM. S. mutans was cultured for further 18 h as before. The probiotic supernatant without bacteria was used as control. The deproteinized supernatants of S. mutans were collected and stored as described above.

Metabolite Assays

The metabolite production of lactate, H2O2 and ammonia was measured via assessing their concentration in the deproteinized supernatants using colorimetric assay kits (Sigma-Aldrich) in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions. The determination of reuterin in the supernatants was analyzed as described elsewhere (Kang et al., 2011) with some modifications. In short, 250 μL of deproteinized probiotic supernatant samples were added to 187.5 μL of 10 mM tryptophan dissolved in 0.05 M HCl, followed by 750 μL of 37% HCl. Under acidic conditions, tryptophan and the aldehyde of reuterin form a β-carboline derivative which oxidizes to produce a purple pigment. After incubation at 37°C for 20 min, the absorbance was measured at 560 nm. Acrolein (Sigma) was used as the calibration standard. To obtain standard curve, 0–15 μmol of acrolein was added to 1 mL of distilled water. The detection of absorbance was performed by the 96 well plate spectrophotometer Multiskan Go (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany).

Viable Bacteria Enumeration

Viable bacteria cells were determined by plating 100 μL aliquots of 1 mL serial dilutions on COLS+ agar plates for S. oligofermentans and S. mutans or on MRS agar plates for L. reuteri. After 1–2 days of aerobic incubation at 37°C, the colony forming units/mL (CFU/mL) were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed, and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test conducted, with P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. SPSS Version 20.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

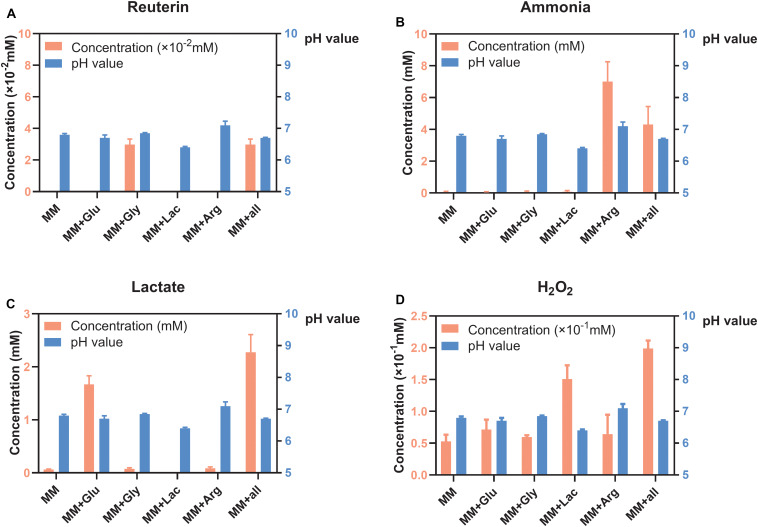

Concentration of Metabolites of S. oligofermentans Under Different Environmental Conditions

S. oligofermentans produced very little reuterin in MM+Gly and MM+all (Figure 1A). Ammonia was detected in MM+Arg and MM+all (Figure 1B) and lactate was detectable mainly in MM+Glu and MM+all (Figure 1C). H2O2 was produced in all groups, with the highest concentration in MM+all (Figure 1D). The pH of the supernatants after the incubation of S. oligofermentans were MM 6.80, MM+Glu 6.70, MM+Gly 6.85, MM+Lac 6.40, MM+Arg 7.10, MM+all 6.70 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Concentration of metabolites and pH of S. oligofermentans in six different MM media (means ± standard deviations, n = 3); minimal medium (MM), MM with glucose (MM+Glu), MM with glycerol (MM+Gly), MM with Lactic acid (MM+Lac), MM with arginine (MM+Arg) and all-full medium (MM+all). The left Y axis showed the concentration and the right Y axis showed the pH value. (A) Very little reuterin was produced in S. oligofermentans. (B) Ammonia was detected in MM+Arg and MM+all. (C) Lactate was detectable mainly in MM+Glu and MM+all. (D) H2O2 was produced in all groups.

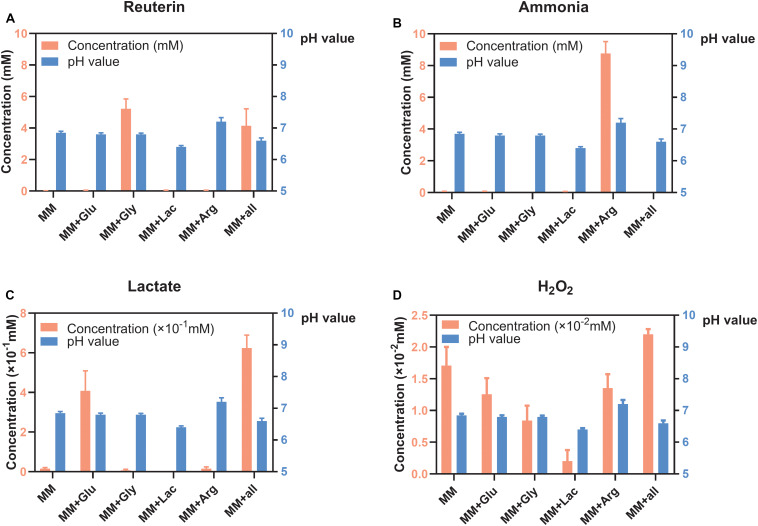

Concentration of Metabolites of L. reuteri in Six Different MM Medium

Reuterin was detected in both MM+Gly and MM+all (Figure 2A), while ammonia was only detected in MM+Arg (Figure 2B). Lactate was detected in MM+Glu and MM+all, with only very low concentrations in the other groups (Figure 2C). H2O2 was produced in all groups, the highest concentration being measured in MM+all (Figure 2D). The pH of the supernatants after the incubation of L. reuteri were MM 6.85, MM+Glu 6.80, MM+Gly 6.80, MM+Lac 6.40, MM+Arg 7.20, MM+all 6.60 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Concentration of metabolites and pH of L. reuteri (means ± standard deviations, n = 3) in six different MM media; minimal medium (MM), MM with glucose (MM+Glu), MM with glycerol (MM+Gly), MM with Lactic acid (MM+Lac), MM with arginine (MM+Arg) and all-full medium (MM+all). The left Y axis showed the concentration and the right Y axis showed the pH value. (A) Reuterin was detected in both MM+Gly and MM+all. (B) Ammonia was only detected in MM+Arg. (C) Lactate was mainly produced in MM+Glu and MM+all. (D) H2O2 was produced in all groups, the lowest being in MM+Lac.

Effect of Probiotic Supernatants on S. mutans Metabolic Activity

Lactate production of S. mutans was minimal (1.78 ± 0.65 × 10–2 mM) in control medium without glucose, and significantly higher in control media with glucose. Cultivation in supernatant of S. oligofermentans significantly reduced the lactate production of S. mutans regardless of the medium (Table 1) and, via utilization of lactate by S. mutans, even decreased the concentration of lactate in MM+all (concentration decreased by −2.14 ± 0.35 mM) and MM+Lac+Glu (concentration decreased by −1.39 ± 0.25 mM) respectively, (p < 0.001). Cultivation in supernatant of L. reuteri also significantly reduced the lactate production of S. mutans in all media except MM+Lac+Glu (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Changes (means ± standard deviations, n = 3/group) in lactate concentration (mM) of S. mutans (Sm) after cultivation in the supernatant (Sup.) of S. oligofermentans (So) and L. reuteri (Lr).

| Metabolite (mM) | Minimal medium | Bacterial strain |

||

| Sm | Sm Sup. SoA | Sm Sup. LrB | ||

| Lactate | MM | 1.78 ± 0.65 × 10−2 | −5.14 ± 0.50 × 10−2*** | −1.13 ± 1.08 × 10−2** |

| MM+Glu | 6.52 ± 0.91 | 3.84 ± 0.40** | 2.95 ± 0.31** | |

| MM+Gly+Glu | 5.00 ± 0.42 | 3.01 ± 0.49** | 3.65 ± 0.33 × 10−1*** | |

| MM+Lac+Glu | 4.46 ± 0.41 | −1.39 ± 0.25*** | 4.42 ± 0.19 | |

| MM+Arg+Glu | 6.03 ± 0.48 | 1.69 ± 0.43*** | 3.29 ± 0.26*** | |

| MM+all | 6.00 ± 0.29 | −2.14 ± 0.35*** | −0.46 ± 0.11*** | |

For the culture of S. mutans, in order to enable it to produce lactate, the same concentration of glucose (5 mM) as in MM+Glu and MM+all was additionally added to MM+Gly, MM+Lac, MM+Arg. Glucose was also added to the probiotic supernatants of MM+Gly, MM+Lac, and MM+Arg. S. mutans was cultivated in minimal medium (MM), MM with glucose (MM+Glu), MM with glycerol and glucose (MM+Gly+Glu), MM with Lactic acid and glucose (MM+Lac+Glu), MM with arginine and glucose (MM+Arg+Glu) and all-full medium (MM+all). The lactate concentration of S. mutans cultivated in probiotic supernatants (test samples) and the lactate concentration in probiotic supernatants without S. mutans (control samples) were measured. The lactate production of S. mutans cultured in probiotic supernatants was calculated by subtracting the amount of lactate in control samples from the amount of lactate in corresponding test samples. Positive values indicate additional lactate production, negative values indicate uptake of lactate by bacteria. Dunnett’s test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, versus Sm.

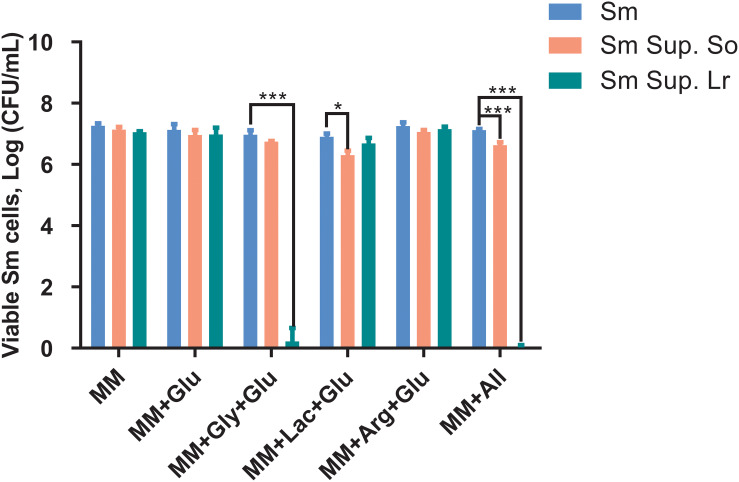

Inhibitory Effect of the Probiotic Supernatants on the Survival of S. mutans

When cultured in supernatants of S. oligofermentans and L. reuteri, survival of S. mutans was reduced compared with the controls (Figure 3). Specifically, treatment with the supernatant of S. oligofermentans resulted in a reduction in the viability of S. mutans in MM+Lac+Glu and MM+all by 0.6-log10 and 0.5-log10, respectively. Moreover, in MM+Gly+Glu and MM+all group, supernatant of L. reuteri yielded a reduction in viability of 6.1-log10 and 7.1-log10, respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in colony-forming units (Log CFU/mL, means ± standard deviations) of S. mutans after being cultured in the supernatant (Sup.) of S. oligofermentans (So) and L. reuteri (Lr). S. mutans was cultivated in minimal medium (MM), MM with glucose (MM+Glu), MM with glycerol and glucose (MM+Gly+Glu), MM with Lactic acid and glucose (MM+Lac+Glu), MM with arginine and glucose (MM+Arg+Glu) and all-full medium (MM+all) (controls), as well as supernatants of the probiotics. Glucose was additionally added to the MM+Gly, MM+Lac, and MM+Arg group of probiotic supernatants as it is described in section “Culture of S. mutans With Probiotic Supernatants.” Each experiment was repeated three times. Dunnett’s test: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, versus controls.

Discussion

The present study investigated the potential of S. oligofermentans and L. reuteri to produce different antimicrobial substances under different environmental conditions, and tested the inhibitory effect of probiotic supernatants on lactate production and survival of S. mutans. We found that both probiotics produced H2O2 in different MM, and ammonia in MM+Arg. In MM containing glycerol, L. reuteri also produced reuterin. Both probiotics produced lactate when glucose was present. Cultivation in the supernatants of both probiotics reduced the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans significantly and environment-specifically. It can be assumed that these effects were not associated with pH changes (which were minimal given the buffering capacity of the used media), but associated with the products generated by the probiotics (Castillo et al., 2000). We hence confirm our hypothesis.

The mechanism by which probiotics precisely interfere with cariogenic pathogens remains unknown. There are currently three possible explanations, including (1) release of bacteriocins (Martinez et al., 2013), (2) the antimicrobial effects through co-aggregation (Lang et al., 2010), (3) competition with cariogenic bacteria for nutrition and adhesion (Terai et al., 2015; Schwendicke et al., 2017). In this study, S. mutans was cultured in the supernatant of probiotics only. Hence, we can make certain assumptions as to how these supernatants interacted with S. mutans: In MM+Lac and MM+all, S. oligofermentans had produced large amounts of H2O2, which has likely impacted on the survival and lactate production of S. mutans. In MM+Gly and MM+all, L. reuteri produced large amounts of reuterin, with potentially even more pronounced effects on S. mutans. The production of ammonia by S. oligofermentans in arginine containing medium had only moderate inhibitory effects on S. mutans activity and survival. Note that we cannot fully exclude the observed effects to be associated with other, non-measured probiotic products present in the supernatant, but given the consistency and plausibility of the measured presence of H2O2 and reuterin and the observed effects on S. mutans, the outlined pathway of how probiotics impact on S. mutans seems likely.

H2O2 is the major antibacterial substance produced by S. oligofermentans (Zhang et al., 2010; Tong et al., 2020), as confirmed by our study. S. oligofermentans possesses three H2O2-forming enzyme: lactate oxidase (Lox), that catalyzes L-lactate and oxygen to produce H2O2 and pyruvate; pyruvate oxidase (Pox), that generates H2O2 by oxidizing pyruvate to acetate via acetyl coenzyme; L-amino acid oxidase, that catalyzes the production of H2O2 from amino acids and peptone (Tong et al., 2008; Liu L. et al., 2012). Our findings that H2O2 production was most pronounced in MM+Lac and MM+all, where lactic acid was available for Lox, suggest that Lox may play a role in H2O2 generation. The production of H2O2 in MM, MM+Glu, MM+Gly and MM+Arg was similar, presumably because S. oligofermentans had converted extracellular glucose into intracellular polysaccharides during precultivation in BHI+glucose. When cultivated in carbohydrate-limited MM variations, intracellular glucose or glycogen of S. oligofermentans was decomposed into pyruvate. Pyruvate can generate H2O2 and acetyl phosphate through Pox or can be converted into lactic acid by the lactate dehydrogenase. The additional availability of glucose in MM+all may further support Pox and Lox activity, as S. oligofermentans converted glucose into pyruvate and lactate, which act as substrates for Pox and Lox, respectively. Overall, S. oligofermentans requires a Pox-Lox synergy to produce the maximum amount of H2O2 (Liu L. et al., 2012).

Saliva and protein-rich foods contain abundant amounts of arginine. The arginine deiminase system degrades and metabolizes arginine to ammonia (Nascimento, 2018), which raises the pH (Liu Y. L. et al., 2012). For S. oligofermentans, we found that ammonia can be detected in MM+Arg and MM+all. The lower ammonia production in MM+all may be explained by excess glucose being present, with the arginine deiminase activity decreasing when glucose concentrations exceed 2 mM (Crow and Thomas, 1982; Kanapka and Kleinberg, 1983). Ammonia had only moderate effect on S. mutans activity and survival, which may be expected. Anti-caries effects of ammonia will be relevant nevertheless via altering the pH to a less cariogenic environment, hence supporting to rebalance remineralization over demineralization and preventing net mineral loss (Zaura and Twetman, 2019).

Reuterin is a multi-compound dynamic equilibrium system composed of 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde (3-HPA), its hydrate and dimer (Spinler et al., 2008) as well as acrolein. 3-HPA is a product of glycerol dehydration in the propanediol utilization (Pdu) pathway and is catalyzed by glycerol dehydratase (Chen and Hatti-Kaul, 2017). In reuterin solutions, acrolein and 3-HPA are interconverted, with acrolein being the active antimicrobial compound (Engels et al., 2016). In this study, we found S. oligofermentans to produce very little reuterin in MM+Gly and MM+all. L. reuteri, however, is known to possess the Pdu pathway to produce reuterin via fermentation of glycerol. After cultivation in the reuterin-containing supernatant of L. reuteri, S. mutans survival was reduced nearly completely. Our results are in line with those from clinical studies finding L. reuteri to be an efficacious probiotic to combat oral pathogens (Lin et al., 2017; Geraldo et al., 2019).

It has also been shown that L. reuteri is capable of producing H2O2 (Kang et al., 2011; Basu et al., 2019), and in our experiments, L. reuteri produced H2O2 in each MM variation. H2O2 is mainly produced by Pox (as described) and NADH oxidase (Nox) (Hertzberger et al., 2014), while it is unclear which enzymatic pathway was relevant in our setting. It was found that Pox synthesis was inhibited when glucose was abundantly available, while Nox was not essentially affected (Sedewitz et al., 1984). This was not the case in MM+Glu in our study. Hence, we assume that H2O2 was largely produced through NADH-dependent reactions, as shown for Lactobacillus delbrueckii, too (Marty-Teysset et al., 2000).

To assess the influence of the products generated by the probiotics on the lactate production and survival of S. mutans, S. mutans was cultivated in the probiotic supernatants. When cultivated in S. oligofermentans supernatant, lactate production by S. mutans in each MM variation group was significantly reduced. Since the supernatants of each MM variation media contained H2O2, the reason for this decrease in lactate production may be related to H2O2. Furthermore, ammonia produced in MM+Arg+Glu and MM+all may also neutralize lactic acid produced by S. mutans, reminding us that adjustment the alkali-generation potential of oral microbial may also have great potential. A similar reduction in lactate production was found when S. mutans was cultured in L. reuteri supernatants for all groups except MM+Lac+Glu. We consider that it is because the amount of H2O2 in MM+Lac+Glu was too small to reach an effective concentration.

Our findings agree with the study of Rossoni et al. (2018) in which they found the growth of S. mutans in planktonic cultures was inhibited by the bioactive substances released by Lactobacillus strains. In our study, almost no CFU were detectable in MM+Gly+Glu and MM+all of L. reuteri supernatant, proving reuterin as a potentially powerful antibiotic substance. S. mutans showed significantly lower survival in the culture of the supernatants in MM+Lac+Glu and MM+all of S. oligofermentans, which indicated that large amounts of H2O2 produced in a lactate-rich environment may have an inhibitory effect on the survival of S. mutans.

Overall, our study demonstrated that the products generated by the probiotics in the supernatants may inhibit the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans and this effect was environment-specific. While it may well be that additional benefits emerge from the usage of viable probiotic, e.g., via co-aggregation (probably between L. reuteri and S. mutans), competition with cariogenic bacteria for nutrients and adhesive surfaces, and isolation of substrate or metal ions, our findings open up new therapeutic avenues. Using supernatant or specific isolated compounds for inhibiting cariogenic pathogens comes with the advantage of being safer, easier to dose, and any product having an extended shelf-life compared with living probiotics. Understanding the interactions between probiotics and cariogenic bacteria in simulated oral environments and identifying the underlying molecular mechanisms may support more effective and safe applications.

This study has several limitations. First, the complex oral conditions cannot be completely simulated in vitro. The impact of other bacteria species and the relevance of further proteins being available for bacterial metabolization will likely modify our findings. For the sake of interpretability, however, a simplified model such as ours seems useful. Second, our method for detecting specific bacterial substances produced by probiotics using colorimetric assays was not comprehensive; a more detailed metabolomic analysis may yield further insights. Similar, determining the CFU/mL of S. mutans in planktonic bacterial cultures to assess survival inhibition comes with limitations and does not fully reflect that probiotic effects in a clinical setting should target dental biofilms. However, both the colorimetric assay and the enumeration of planktonic bacteria via CFU/mL were chosen as they are easy to operate, reproducible and sufficient for the purposes of this study. Third, the culture time used in this study were optimized to capture, in a limited amount of time, the specific impact of the different metabolites. Different culture periods will be associated with different degrees of bacterial interaction. Last, there may be other mechanism, like end-product inhibition, as a possible non-specific mechanism that leads to a decrease in lactate production of S. mutans. However, the actual impact of this mechanism on our experimental results requires further verification.

In conclusion and within these limitations, the probiotic effects of S. oligofermentans and L. reuteri supernatants on the metabolic activity and survival of S. mutans were environment-specific through different pathways. Future studies as well as clinical applications should consider environment-specific probiotic actions on cariogenic pathogens.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

HY performed the experiments, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. PG and HY conceived and designed the study. PG guided the experiments and revised the manuscript. FS conceived the study, guided the design of the experiments, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors had approved the final version of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank BioGaia company for kindly providing us with the Limosilactobacillus reuteri, ATCC PTA 5289 strain. We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG SCHW 1766/2-2) and China Scholarship Council (CSC) (Grant # 201708440325).

References

- Aas J. A., Paster B. J., Stokes L. N., Olsen I., Dewhirst F. E. (2005). Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43 5721–5732. 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., de Soet J. J., Tong H., Gao X., He L., van Loveren C., et al. (2015). Streptococcus oligofermentans inhibits Streptococcus mutans in biofilms at both neutral pH and cariogenic conditions. PLoS One 10:e130962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu T. P., Long A. R., Nelson B. J., Kumar R., Rosenberg A. F., Gray M. J. (2019). Complex responses to hydrogen peroxide and hypochlorous acid by the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri. mSystems 4:e00453-19. 10.1128/mSystems.00453-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M., Nart J., Audivert S., Bonachera M. A., Alemany A. S., Fuentes M. C., et al. (2012). Isolation and characterization of probiotic strains for improving oral health. Arch. Oral Biol. 57 539–549. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burne R. A., Marquis R. E. (2000). Alkali production by oral bacteria and protection against dental caries. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 193 1–6. 10.1016/S0378-1097(00)00438-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo A., Rubiano S., Gutierrez J., Hermoso A., Liebana J. (2000). Post-pH effect in oral streptococci. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 6 142–146. 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2000.00030.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Hatti-Kaul R. (2017). Exploring Lactobacillus reuteri DSM20016 as a biocatalyst for transformation of longer chain 1,2-diols: limits with microcompartment. PLoS One 12:e185734. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clancy K. A., Pearson S., Bowen W. H., Burne R. A. (2000). Characterization of recombinant, ureolytic Streptococcus mutans demonstrates an inverse relationship between dental plaque ureolytic capacity and cariogenicity. Infect Immun. 68 2621–2629. 10.1128/iai.68.5.2621-2629.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow V. L., Thomas T. D. (1982). Arginine metabolism in lactic streptococci. J. Bacteriol. 150 1024–1032. 10.1128/jb.150.3.1024-1032.1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doleyres Y., Beck P., Vollenweider S., Lacroix C. (2005). Production of 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde using a two-step process with Lactobacillus reuteri. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 68 467–474. 10.1007/s00253-005-1895-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels C., Schwab C., Zhang J., Stevens M. J. A., Bieri C., Ebert M. O., et al. (2016). Acrolein contributes strongly to antimicrobial and heterocyclic amine transformation activities of reuterin. Sci. Rep. 6:36246. 10.1038/srep36246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exterkate R. A., Crielaard W., Ten C. J. (2010). Different response to amine fluoride by Streptococcus mutans and polymicrobial biofilms in a novel high-throughput active attachment model. Caries Res. 44 372–379. 10.1159/000316541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganas P., Schwendicke F. (2019). Effect of reduced nutritional supply on the metabolic activity and survival of cariogenic bacteriain in vitro. J. Oral Microbiol. 11:1605788. 10.1080/20002297.2019.1605788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzle M. G., Holtzel A., Walter J., Jung G., Hammes W. P. (2000). Characterization of reutericyclin produced by Lactobacillus reuteri LTH2584. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 4325–4333. 10.1128/aem.66.10.4325-4333.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraldo B., Batalha M. N., Milhan N., Rossoni R. D., Scorzoni L., Anbinder A. L. (2019). Heat-killed Lactobacillus reuteri and cell-free culture supernatant have similar effects to viable probiotics during interaction with Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Periodontal. Res. 55 215–220. 10.1111/jre.12704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruner D., Paris S., Schwendicke F. (2016). Probiotics for managing caries and periodontitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. 48 16–25. 10.1016/j.jdent.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberger R., Arents J., Dekker H. L., Pridmore R. D., Gysler C., Kleerebezem M., et al. (2014). H2O2 production in species of the lactobacillus acidophilus group: a central role for a novel NADH-dependent flavin reductase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 2229–2239. 10.1128/AEM.04272-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalasvuori H., Haukioja A., Tenovuo J. (2012). Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri strains ATCC PTA 5289 and ATCC 55730 differ in their cariogenic properties in vitro. Arch. Oral Biol. 57 1633–1638. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A., Scholz C., Kilian M. (2016). Re-evaluation of the taxonomy of the Mitis group of the genus Streptococcus based on whole genome phylogenetic analyses, and proposed reclassification of Streptococcus dentisani as Streptococcus oralis subsp. dentisani comb. nov., Streptococcus tigurinus as Streptococcus oralis subsp. tigurinus comb. nov., and Streptococcus oligofermentans as a later synonym of Streptococcus cristatus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 4803–4820. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanapka J. A., Kleinberg I. (1983). Catabolism of arginine by the mixed bacteria in human salivary sediment under conditions of low and high glucose concentration. Arch. Oral Biol. 28 1007–1015. 10.1016/0003-9969(83)90055-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M., Oh J., Lee H., Lim H., Lee S., Yang T.-H., et al. (2011). Inhibitory effect of Lactobacillus reuteri on periodontopathic and cariogenic bacteria. J. Microbiol. 49 193–199. 10.1007/s12275-011-0252-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C., Bottner M., Holz C., Veen M., Ryser M., Reindl A., et al. (2010). Specific Lactobacillus/mutans Streptococcus co-aggregation. J. Dent. Res. 89 175–179. 10.1177/0022034509356246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X., Chen X., Tu Y., Wang S., Chen H. (2017). Effect of probiotic Lactobacilli on the growth of Streptococcus mutans and multispecies biofilms isolated from children with active caries. Med. Sci. Monit. 23 4175–4181. 10.12659/MSM.902237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. B., Lohans C. T., Duar R., Zheng J., Vederas J. C., Walter J., et al. (2015). Genetic determinants of reutericyclin biosynthesis in Lactobacillus reuteri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 2032–2041. 10.1128/AEM.03691-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Tong H., Dong X. (2012). Function of the pyruvate oxidase-lactate oxidase cascade in interspecies competition between Streptococcus oligofermentans and Streptococcus mutans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78 2120–2127. 10.1128/AEM.07539-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Chu L., Wu F., Guo L., Li M., Wang Y., et al. (2014). Influence of pH on inhibition of Streptococcus mutans by Streptococcus oligofermentans. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 122 57–61. 10.1111/eos.12102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. L., Nascimento M., Burne R. A. (2012). Progress toward understanding the contribution of alkali generation in dental biofilms to inhibition of dental caries. Int. J. Oral Sci. 4 135–140. 10.1038/ijos.2012.54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh P. D. (2006). Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community – implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health 6(Suppl 1):S14. 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez F. A., Balciunas E. M., Converti A., Cotter P. D., de Souza O. R. (2013). Bacteriocin production by Bifidobacterium spp. a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 31 482–488. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marty-Teysset C., de la Torre F., Garel J. (2000). Increased production of hydrogen peroxide by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus upon aeration: involvement of an NADH oxidase in oxidative stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 262–267. 10.1128/aem.66.1.262-267.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meurman J. H. (2005). Probiotics: do they have a role in oral medicine and dentistry? Eur. J. Oral Sci. 113 188–196. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Q., Tavella V. J., Luo X. M. (2018). Role of Lactobacillus reuteri in human health and diseases. Front. Microbiol. 9:757. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento M. M. (2018). Potential uses of arginine in dentistry. Adv. Dent. Res. 29 98–103. 10.1177/0022034517735294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S. C., Hart A. L., Kamm M. A., Stagg A. J., Knight S. C. (2009). Mechanisms of action of probiotics: recent advances. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 15 300–310. 10.1002/ibd.20602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossoni R. D., Velloso M. D. S., de Barros P. P., de Alvarenga J. A., Santos J. D. D., Prado A. C. C. D. S., et al. (2018). Inhibitory effect of probiotic Lactobacillus supernatants from the oral cavity on Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Microb. Pathog. 123 361–367. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendicke F., Korte F., Dörfer C. E., Kneist S., Fawzy El-Sayed K., Paris S. (2017). Inhibition of Streptococcus mutans growth and biofilm formation by probiotics in vitro. Caries Res. 51 87–95. 10.1159/000452960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedewitz B., Schleifer K. H., Gotz F. (1984). Physiological role of pyruvate oxidase in the aerobic metabolism of Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Bacteriol. 160 462–465. 10.1128/jb.160.1.462-465.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinler J. K., Taweechotipatr M., Rognerud C. L., Ou C. N., Tumwasorn S., Versalovic J. (2008). Human-derived probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri demonstrate antimicrobial activities targeting diverse enteric bacterial pathogens. Anaerobe 14 166–171. 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talarico T. L., Dobrogosz W. J. (1989). Chemical characterization of an antimicrobial substance produced by Lactobacillus reuteri. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33 674–679. 10.1128/aac.33.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terai T., Okumura T., Imai S., Nakao M., Yamaji K., Ito M., et al. (2015). Screening of probiotic candidates in human oral bacteria for the prevention of dental disease. PLoS One 10:e128657. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H. (2003). Streptococcus oligofermentans sp. nov., a novel oral isolate from caries-free humans. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 53 1101–1104. 10.1099/ijs.0.02493-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H., Chen W., Merritt J., Qi F., Shi W., Dong X. (2007). Streptococcus oligofermentans inhibits Streptococcus mutans through conversion of lactic acid into inhibitory H2O2: a possible counteroffensive strategy for interspecies competition. Mol. Microbiol. 63 872–880. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05546.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H., Chen W., Shi W., Qi F., Dong X. (2008). SO-LAAO, a novel L-amino acid oxidase that enables Streptococcus oligofermentans to outcompete Streptococcus mutans by generating H2O2 from peptone. J. Bacteriol. 190 4716–4721. 10.1128/JB.00363-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong H., Dong Y., Wang X., Hu Q., Yang F., Yi M., et al. (2020). Redox-regulated adaptation of Streptococcus oligofermentans to hydrogen peroxide stress. mSystems 5:e00006-20. 10.1128/mSystems.00006-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong L., Sissions C. H. (2001). A comparison of human dental plaque microcosm biofilms grown in an undefined medium and a chemically defined artificial saliva. Arch. Oral Biol. 46 477–486. 10.1016/S0003-9969(01)00016-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaura E., Twetman S. (2019). Critical appraisal of oral pre- and probiotics for caries prevention and care. Caries Res. 53 514–526. 10.1159/000499037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Tong H. C., Dong X. Z., Yue L., Gao X. J. (2010). A preliminary study of biological characteristics of Streptococcus oligofermentans in oral microecology. Caries Res. 44 345–348. 10.1159/000315277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J., Wittouck S., Salvetti E., Franz C., Harris H., Mattarelli P., et al. (2020). A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 70:4107. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.