Gastric electrical stimulation (GES) is an accepted form of therapy for gastroparesis and is considered for compassionate therapy in patients with refractory nausea and vomiting.1 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved GES for treatment of drug-refractory idiopathic gastroparesis and diabetic gastroparesis because it has been shown to improve nausea and reduce vomiting frequency. It has also been used off label for related conditions.2,3 We present a case highlighting the methods and importance of performing endoscopy intraoperatively during placement of the permanent GES device and discuss possible adverse events that may arise.

Materials and methods

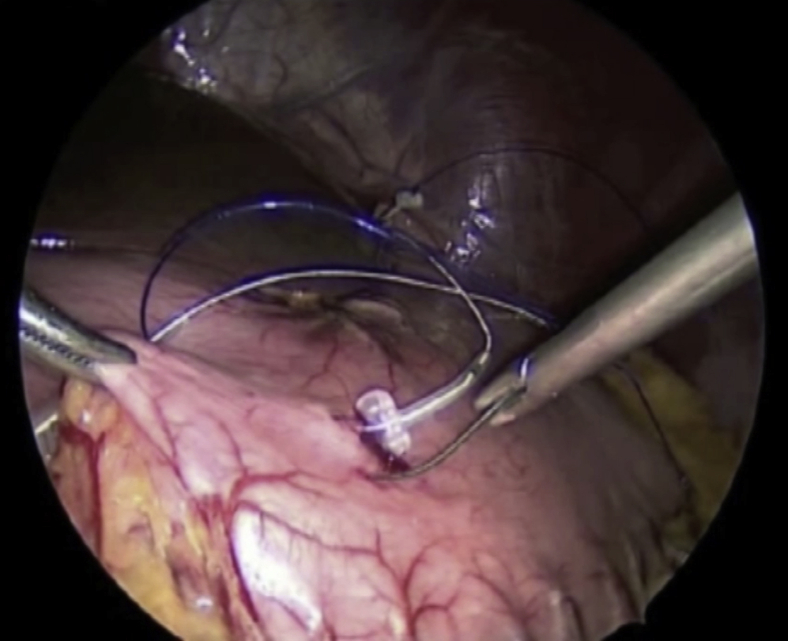

Once a patient has been selected for permanent gastric stimulator placement, a surgical procedure is performed in which a pocket for the device is created in the subcutaneous tissues of the abdomen and leads are placed that run internally from the device to the gastric muscularis propria, as shown in Video 1 (available online at www.VideoGIE.org) (Fig. 1). Several adverse events may arise from this procedure, including bleeding, pocket site and systemic infection, and lead migration. Any of these adverse events are possible postoperatively, but their risk may be reduced by intraoperative endoscopy, to ensure that no lead perforation into the gastric lumen has occurred.

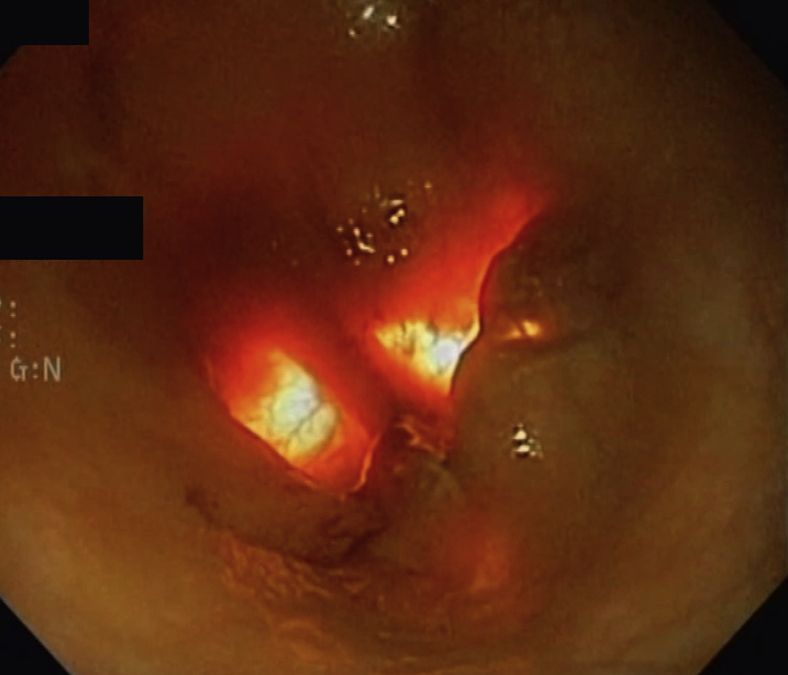

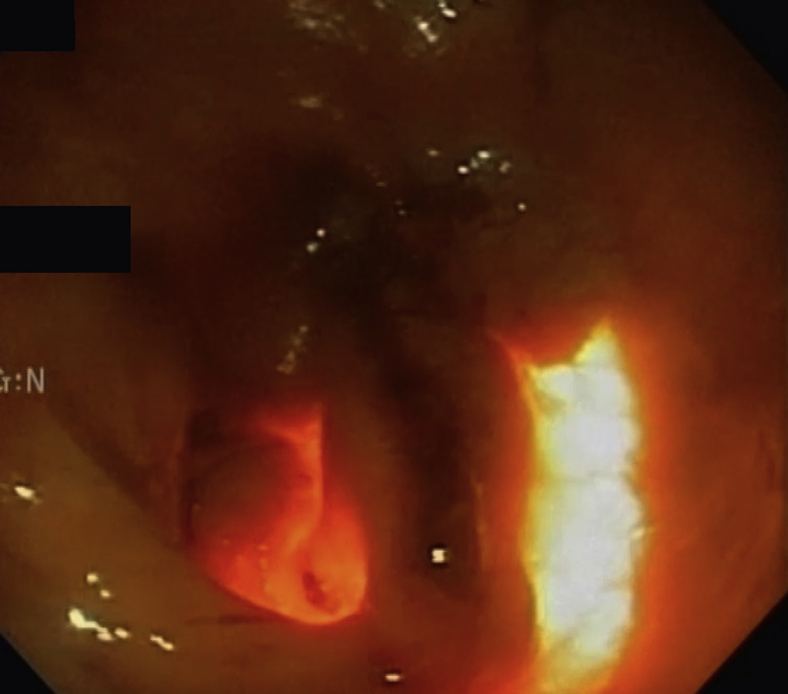

Figure 1.

Endoclip from prior transnasal temporary gastric stimulator lead still attached to gastric mucosa.

In Video 1, we also show an endoscopy done during a permanent GES placement. A midline incision is made, and the stomach is identified. An area near the body-antral junction 8 to 10 cm proximal to the pylorus is found and confirmed endoscopically. This is the area where the leads will be placed. Once lead placement is completed, an endoscopy is typically performed. The area where leads were placed is viewed endoscopically to ensure no lead perforation. Determining this location endoscopically can at times be difficult. To perform the examination, the stomach is insufflated, and the surgeon may palpate externally to guide the endoscopist (Fig. 2).

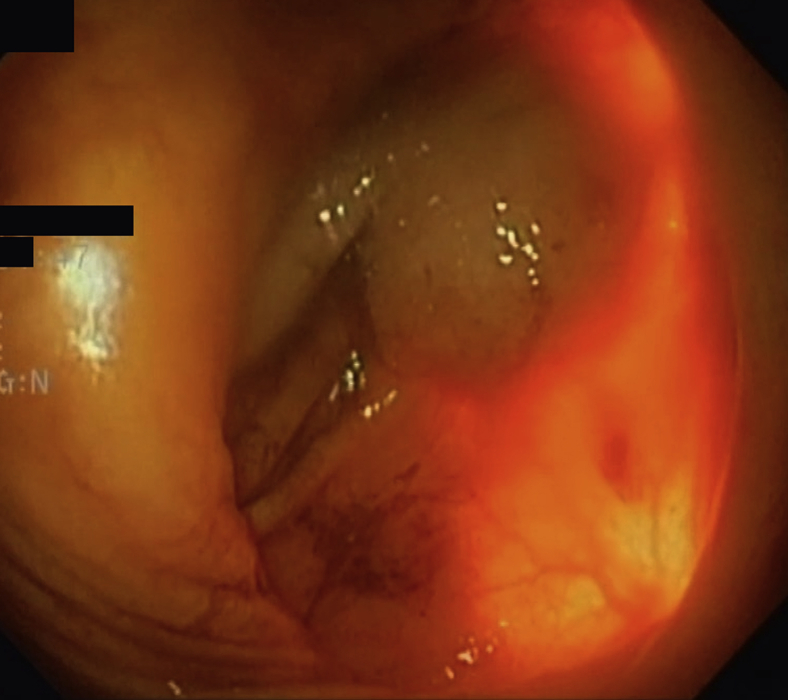

Figure 2.

Endoscopic view intraoperatively during permanent gastric electrical stimulation placement. Transillumination from the operating room light can be seen through the distal stomach as well as the surgeon palpating the area as seen on the right.

Light from the operating room may also provide transillumination of the area exposed for lead placement. If leads can be seen entering the gastric lumen, they are removed by the surgeon and replaced (Fig. 3). The area is then examined again to re-evaluate for perforation. It is important to ensure no lead perforation has occurred because this can lead to malfunction, infection, and sometimes total perforation of the leads into the gastric mucosa.

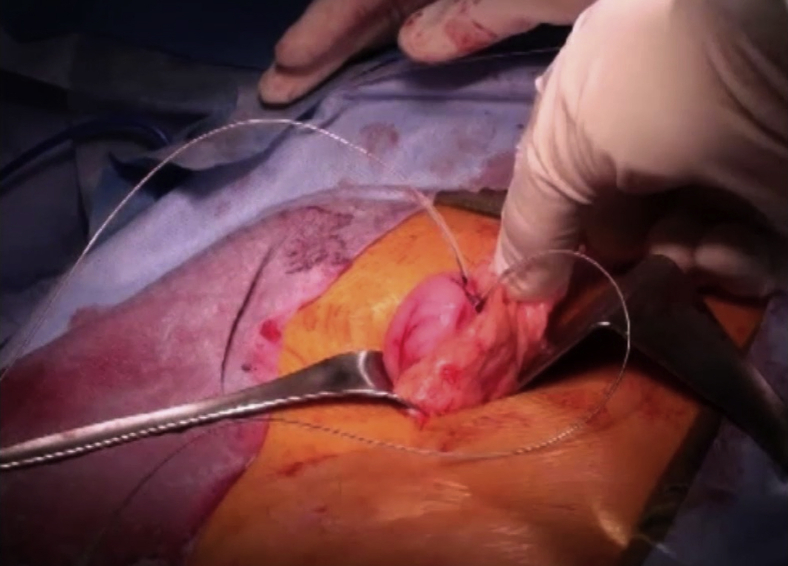

Figure 3.

Surgeon palpating the site of the permanent gastric electrical stimulation lead to guide the endoscopist. No lead is seen, confirming no perforation by the gastric leads.

Once the endoscopy has confirmed no perforation is present, the endoscope is withdrawn and the surgeon proceeds (Fig. 4). Occasionally, a lead may break or be pulled during the remaining portions of the surgery. If this occurs, the endoscopy is repeated as described.

Figure 4.

Endoscopic view of a recently performed full-thickness gastric biopsy site, seen in the center of the screen.

Results

The patient underwent successful implantation of permanent GES after screening with temporary GES (Fig. 5). Intraoperative endoscopy confirmed successful placement of GES leads without perforation into the gastric lumen. The patient was followed up in clinic 1 month after placement, and device settings were adjusted as appropriate.

Figure 5.

External view of the gastric stimulator leads attached to the gastric body.

Discussion

Gastroparesis and gastroparesis-like syndrome can be difficult entities to treat. Often, patients have tried and failed a variety of therapies. The techniques for endoscopic and surgical placement of GES are not widely known or performed. The purpose of this article is to highlight several important endoscopic aspects of permanent GES placement. In general, several adverse events may arise from permanent stimulator placement, including bleeding, infection, and lead migration. It is important for the endoscopist to be aware of the risk of lead perforation, which may lead to any of the adverse events listed. Lead perforation may be ruled in or out based on endoscopy findings at the time of surgery, thus lowering the risk for postoperative adverse events.

Disclosure

Dr Abell is a reviewer for UpToDate; has received grant funding from Censa, Vanda, and Allergan; holds stock in ADEPT-PI; is an editor for Medstudy, Neuromodulation, and Wikistim; and is a consultant for Censa and Nuvaira. All other authors disclosed no financial relationships.

Supplementary data

An endoscopy done during a permanent gastric electrical stimulation placement.

References

- 1.Camilleri M., Parkman H.P., Shafi M.A., for the American College of Gastroenterology Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18–37. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.373. quiz 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Grady G., Egbuji J.U., Du P. High-frequency gastric electrical stimulation for the treatment of gastroparesis: a meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2009;33:1693–1701. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0096-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin Z., Forster J., Sarosiek I. Treatment of diabetic gastroparesis by high-frequency gastric electrical stimulation. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1071–1076. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

An endoscopy done during a permanent gastric electrical stimulation placement.