Abstract

Many students and early‐career scientists too often agree to new tasks and chores and end up overworked. Learning how and when to say “no” is therefore an important part of career development.

Subject Categories: S&S: History & Philosophy of Science, Methods & Resources

“Yes” is a positive and reassuring answer, and most people are happy to either give or receive it. But “yes” can also cause problems—overtime, overstretched resources, lower quality, and so on—when someone says yes too often and becomes overwhelmed with too many tasks. An answer of “yes” should only be given when the conditions of agreement fit within one's personal and professional limits. Learning how to say “no” is a tool for developing these boundaries that are essential for a successful career in research. It takes courage to say no, but it maintains liberty by setting limits. Saying no at the appropriate moment is a skill that many young scientists need to learn by their experience, from more experienced members of the team or from their mentor.

PhD students, postdocs, and even young primary investigators often struggle with accommodating their own research work with the expectations and the demands of their colleagues, their team, or department. They often make too many commitments without fully knowing their limits, hoping to make a name for themselves or prove their value. After a myriad of trials, mentees may develop the ability to turn down a seemingly beneficial opportunity that may ultimately encroach on their career development. However, the skill of saying “no” is most often learned by watching how a more experienced member of the science community sets limits on their activities.

When mentors or experienced scientists say no, it therefore comes from long experience or after considering other factors. Mentees may not yet comprehend the full breadth of expectations and demands. Therefore, we suggest that mentees rely on their mentors to learn proper networking and branding before learning when and how to say no. They must first demonstrate dependability and time management skills with fewer tasks to best show their abilities. Saying yes too often may give the impression that you are a people‐pleaser and actually do not know what you want when negotiating tasks. Moreover, it also signifies over‐commitment, which could lead to less self‐care and a decline in productivity. Mentees must have this conversation early and often during the course of their training (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

Too many distractions and not enough saying no can run the risk of limiting mental self‐care to meet others’ expectations. Therefore, it is important to evaluate one's expectations with a mentor through an individual development plan and discuss self‐expectations, others’ expectations, and the importance of both. Haysetta Shuler suggests self‐care should be a part of career development training at universities and medical schools as productivity declines when poor mental health becomes a distraction. To be less stressed means to slow down and say no to tasks that may alter productivity. One must look after oneself first to fend off possible financial, social, physical, and mental problems (Kollack, 2006).

The quality of research is the lifeline to the next grant; thus, saying no to activities that hamper research progression must become an important consideration. Less distractions also mean more time to think and develop new ideas. We like to point out that not all “extra” activities are bad and can help to advance the career, but strategically selecting these extra activities is important. For example, serving on a panel may help you navigate a potential collaboration while joining the research allocation committee at your institution can help you better understand the internal funding mechanisms. Moreover, learning to say no involves more than one approach to accommodate different mentors and activities.

The ability to learn to say no revolves around good mentorship. Learning about an individual's personality and emotional intelligence (EQ)—the competence of individuals to distinguish their own emotions and comprehend those of others, discern between emotional states and manage and adjust emotions to acclimate to novel environments, challenges, or aspirations—will allow mentors to help their mentees develop the skill of saying no while at the same time accepting a no from a mentee. Studies have demonstrated that individuals with high EQ have greater mental health, job performance, and leadership skills. These traits have been attributed to general intelligence and specific personality traits rather than emotional intelligence as a construct (Goleman, 2000). There are various workshops for improving EQ such as the Endocrine Society's Future Leaders Advancing Research in Endocrinology (FLARE) program for research trainees and junior faculty from underrepresented communities. The program offers structured leadership development and in‐depth, hands‐on training in topics ranging from grantsmanship to lab management. Most importantly, increasing awareness of mentee's personality traits will allow mentors to better understand the emotional circumstances contributing to a mentee saying no, which will help the mentor gain acceptance of this response. It is important for mentors to also keep an open mind about the reasoning underlying a no response. The mentee may be enthusiastic about an opportunity but unable to commit due to timing, personal circumstances, or emotional health concerns.

The delivery of a “no” is also a critical skill required to maintain professional relationships; a terse or thoughtless answer can put off colleagues or mentors, and even burn bridges. There are number of strategies for saying no (or yes) so as to prevent too much stress while maintaining the individual academic network.

Decide if an opportunity fits one's creed, augments a CV, fits into long‐term goals, or provides career development enrichment.

Listen to verbal communication.

Observe non‐verbal communication.

Acknowledge the information or opportunity.

Identify any issues with expectations and express compassion in saying no.

Seek peer support and advice prior to saying no, particularly if the thought of saying no is stress‐ or anxiety‐producing.

Give a thoughtful alternative or definitive no and justification for the latter.

Always be open to connecting someone else to the opportunity.

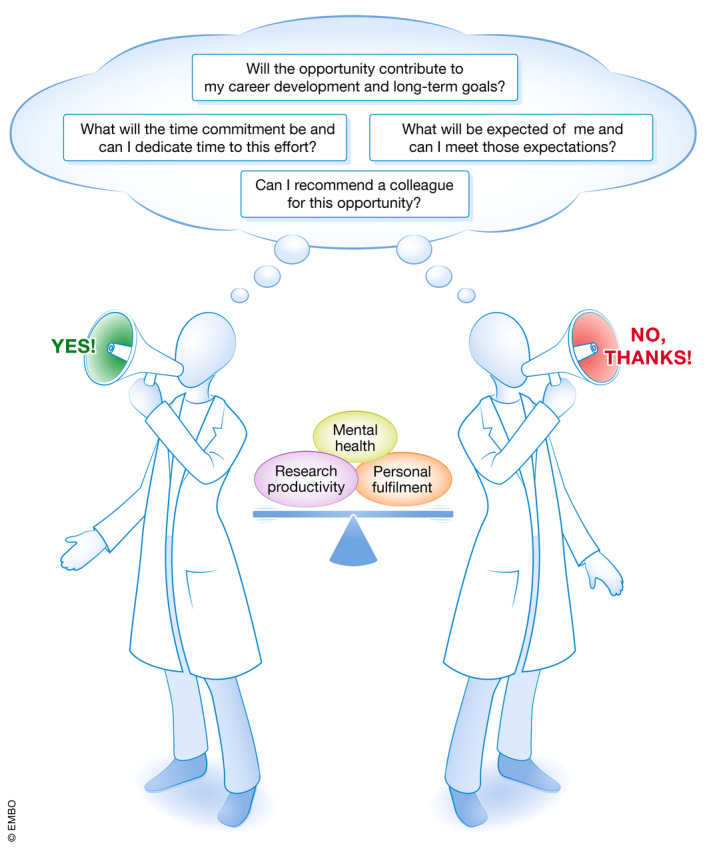

In fact, saying no often affords someone else an opportunity, which also demonstrates maturity and willingness to help others (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Personal and professional considerations to make before accepting or declining participation in an opportunity.

The power of saying “no”.

From our experience as early‐career scientists of color, the ability to progress through the ranks of higher education can also be stymied by expectations to go beyond standard responsibilities, such as sitting on diversity taskforce boards, serving as a supplemental mentor to students of color or participating in community outreach efforts. We encourage minority scientists that are overburdened with activities to reach out to non‐minority allies that can also impart change in their institution to even out the workload while ensuring that diversity issues are given careful attention. Minority mentors themselves do not often say no owing to concerns about being overlooked for the next opportunity (Whittaker et al, 2015). When mentors or mentees collaborate with Hispanic Serving Institutions, Historical Black Colleges and Universities, and tribal colleges, they create an effective support system for selecting opportunities (Whittaker & Montgomery, 2012). However, saying no is an instrument of integrity and a shield against being exploited. “Yes” becomes a commodity. There will always be opportunities, and there are many other students and junior faculty who are willing and capable of taking up the task or challenge. If students and faculty want to advance in research, they need to learn to say “no, thank you” as a “no” can also be opportunity for someone else to show his or her skills. This truly creates a full‐circled paying‐it‐forward moment.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

EMBO Reports (2020) 21: e50918

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders‐IV. pp. 733–734. ISBN 978‐0890420621. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; [Google Scholar]

- Goleman D (2000) Working with emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books; [Google Scholar]

- Kollack I (2006) The concept of self care In Nursing theories: conceptual and philosophical foundations, Kim HS, Kollak I. (eds). p. 45 ISBN 978‐0‐8261‐4006‐7. New York: Springer Publishing Company; [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JA, Montgomery B (2012) Cultivating diversity and competency in STEM: challenges and remedies for removing virtual barriers to constructing diverse higher education communities of success. J Undergrad Neuosci Educ 11: A44–A51 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker JA, Montgomery B, Martinez Acosta VG (2015) Retention of underrepresented minority faculty: strategic initiatives for institutional value proposition based on perspectives from a range of academic institutions. J Undergrad Neurosci Educ 13: A136–A145 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]