Highlights

-

•

COVID-19 is affecting different countries all over the world with great variation in infection rate and death ratio.

-

•

Some reports suggested a relation between the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and the malaria treatment to the infection prevention.

-

•

Some reports related infant's lower-susceptibility to the BCG vaccine. Some other reports a higher risk in males compared to females in such a COVI-19 pandemic.

-

•

Some other reports claimed the possible use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as prophylactic in such a pandemic.

-

•

The-present commentary is to discuss the possible relation between those-factors and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Keywords: BCG, COVID 19, Antimalarial, Gender, Age

Abstract

COVID-19 is affecting different countries all over the world with great variation in infection rate and death ratio. Some reports suggested a relation between the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine and the malaria treatment to the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Some reports related infant's lower susceptibility to the COVID-19. Some other reports a higher risk in males compared to females in such COVID-19 pandemic. Also, some other reports claimed the possible use of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as prophylactic in such a pandemic. The present commentary is to discuss the possible relation between those factors and SARS-CoV-2 infection.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 affected around 5,000,000 around the world with a different percentage of mortality with overall mortality rate of about 6.6% [1]. COVID-19 disease is related to the respiratory infectious diseases caused by coronavirus, the recent attacks of coronavirus were in 2003 caused the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) followed by the Middle east respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012 [2], [3]. Animals are the source for coronaviruses, the Camel for MERS and Civet for SARS, the virus is transferred to these animals from bats [3], [4].

The COVID-19 is transmitted during close contact with infected subject via droplets and fomites. Till now the airborne spread of new coronavirus has not been proven and so this route of transmission is not believed to be the main driver of virus transmission, but also it is possible for the new virus to be transmitted through airborne in specific conditions (e.g. aerosol generating procedures) [5], [6].

Another route which is suspected to play a role in transmission of the infection is the fecal-oral route [7]. This possibility was supported by the results of stool samples analysis through PCR for 8 subjects that were confirmed to be infected with the new coronavirus [7]. Also, another study showed that the genome of the new coronavirus was also detected in the esophagus, stomach, and intestine and this support the possibility of the gastrointestinal route transmission [8].

The majority of subjects have a mild presentation to the infection and mainly start with fever and dry cough that recovers without any interventions; also the flu-like symptoms, malaise, headache, and muscle pain might develop early [9]. Younger subjects represent the majority of mild cases [10]. These mild symptoms might develop to more severe presentation presented as shortness of the breath, that mainly occurs after one week from initial presentation [11], and pneumonia which require hospitalization of the infected subjects. The severity of the infection might progress to develop respiratory failure, multi-organ failure or septic shock [11].

2. Vaccine, age and gender relation to COVID-19 infection

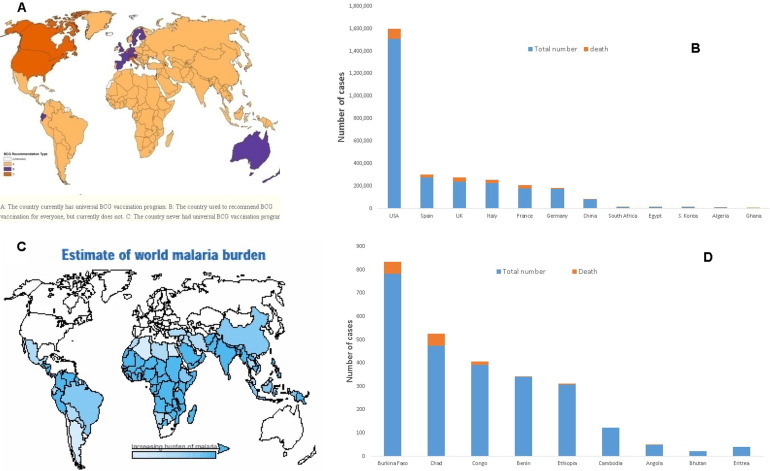

The infection started in China in which more than 80,000 confirmed cases were diagnosed with the new coronavirus, the death rate in China is around 4%, while it is greater than 10% in Italy. SARS-CoV-2 transferred from China to most countries around the world. The spread of the disease became higher in Europe and the USA compared to China (Table 1 ). The number of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 cases detected in countries neighbouring China e.g. Kazakhstan, India, and Korea was lower than that detected in The USA and Europe e.g. Italy, Spain, France, and the UK. To the extent that a close contact area to COVID-19 source, Hong Kong, has around 1000 confirmed-cases with very low mortality-rate of 0.71%. The USA now became the highest country with confirmed COVID-19 cases and progressing. One confusing debate raised right now is the possible relation between the vaccination schedule in different countries and its possible relation to the prevention of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Also, during the current COVID-19 outbreak, it was reported that infants are less susceptible to such a violent virus [10], [12]. One of the proposed explanations is the presence of cross reaction between SARS-CoV-2 and any of childhood vaccines [13]. One of the vaccines that were related to COVID-19 is the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) which originates from an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium Bovis for prevention of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection that causes disseminated and meningeal tuberculosis [14]. Many countries stopped using BCG vaccine except for high risk vulnerable groups [15] e.g. Italy, the USA, the UK, Spain, and France. Other countries are still using BCG vaccine till now e.g. African and Asian countries as shown in Fig. 1 A [16]. Correlating different countries’ SARS-CoV-2 infections and the recorded death rates (Table 1 and Fig. 1B) with Fig. 1A suggests that there is a possible effect of BCG vaccination in decreasing COVID-19 spread and mortality rates in those countries receiving the BCG vaccine. The USA, Spain, Italy, and the UK have the highest number of confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection and mortality even compared to the disease country of origin, China (Table 1 and Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Comparative illustration of relationship between vaccination schedule and total deaths per 1 million people in different countries in a descending arrangement; (data collected on 18 May 2020).

| Countries | BCG | MMR | OPV | Total cases | Total cases/1 million people | Total deaths | Total deaths/1 million people |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgium | No | Yes | Yes | 55,280 | 4,772 | 9,052 | 781 |

| Spain | No | Yes | Yes | 277,719 | 5,940 | 27,650 | 591 |

| Italy | No | Yes | Yes | 225,435 | 3,728 | 31,908 | 528 |

| UK | No | Yes | Yes | 243,695 | 3,592 | 34,636 | 511 |

| France | No | Yes | Yes | 179,569 | 2,752 | 28,108 | 431 |

| Sweden | No | Yes | Yes | 30,143 | 2,987 | 3,679 | 365 |

| Netherlands | No | Yes | Yes | 43,995 | 2,568 | 5,680 | 332 |

| USA | No | Yes | Yes | 1,527,664 | 4,619 | 90,978 | 275 |

| Switzerland | No | Yes | Yes | 30,587 | 3,537 | 1,881 | 218 |

| Canada | No | Yes | Yes | 77,002 | 2,042 | 5,782 | 153 |

| Germany | No | Yes | Yes | 176,651 | 2,109 | 8,049 | 96 |

| Austria | No | Yes | Yes | 16,242 | 1,805 | 629 | 70 |

| Poland | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6,347 | 1,146 | 298 | 54 |

| Croatia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2,226 | 542 | 95 | 23 |

| Russia | Yes | Yes | Yes | 281,752 | 1,931 | 2,631 | 18 |

| Bulgaria | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2,235 | 321 | 110 | 16 |

| Egypt | Yes | Yes | Yes | 12,229 | 120 | 630 | 6 |

| S. Korea | Yes | Yes | Yes | 11,065 | 216 | 263 | 5 |

| China | Yes | Yes | Yes | 82,954 | 58 | 4,634 | 3 |

| Kazakhstan | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6,440 | 343 | 34 | 2 |

| India | Yes | Yes | Yes | 96,169 | 70 | 3,029 | 2 |

| Hong Kong | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1,056 | 141 | 4 | 0.5 |

BCG (Bacillus Calmette-Guérin), MMR (Mumps-Measles-Rubella), OPV (Oral Poliovirus Vaccine).

Fig. 1.

A. Map displaying BCG-vaccination policy by country (adopted from [16]); B. Number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and death cases in certain countries; C. The-estimate of world malaria burden (adopted from [57]); D Number of confirmed COVID-19 cases and death cases for countries receiving antimalarial treatment.

This possibility could be due to the expected preventive immunization role of the BCG vaccine on the lungs and other organs. What is noticeably parallel between Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) and SARS-CoV-2 is that both of them attack primarily the lungs and interfere with host immunity. Besides the main role of the BCG vaccine in the prevention of TB but there is also a sequence of non-specific effects that could be harboured [17]. Such non-specific effects are termed heterologous effects which are commonly accompanied by live attenuated vaccines e.g., BCG, measles vaccine, oral polio vaccine, smallpox vaccine) that have been shown to non-specifically lessen mortality in addition to prevention of the targeted infections especially in low income countries following immunization programs [18] It was reported that live attenuated measles-mumps-rubella vaccine (MMR) could protect against nosocomial infectious diseases and respiratory syncytial virus [19] Heterologous effects of BCG accordingly can protect against non-mycobacterial infections to generally lower respiratory tract infections in children through activation of innate immunity memory based myeloid cells, a process termed trained immunity [20], [21], [22]. BCG vaccination is associated with a 30% reduction in mortality rate by pathogens especially in developing countries [23] and 50% reduction in mortality related to pneumonia [24]. The favourable non-specific effects of the BCG vaccine persist for a time after the neonatal period up to 10 years [25]. Trained immunity is referred to innate immune system that could display memory characteristics, after spiked by pathogens or certain live attenuated vaccines (“training effect”), not only toward the same infectious agents but also non-specifically against different pathogens (cross-protection). Trained immunity cannot be defined as sole innate as it is induced only secondary to primary infection. Meanwhile, it is different than adaptive because it shows non-specific response compared to T/B cell responses [26]. The overall values of trained immunity is attributed to long-term sensitivity of innate immune cells to any microbial stimuli, increasing the response to the same and different subsequent stimuli, and consequently increased cytokine production (not only against TB but also against bacteria, viruses, and even parasites) mediated by monocytes and natural-killer (NK) cells with a memory-like effect via and chromatin remodelling through histone modifications, leading to an enhanced gene transcription upon re-stimulation (especially the up-regulation of IL-1ß) [27], and changes in intracellular metabolism [28], [29], [30], [31]. When trained immunity is induced in monocytes in response to microbial molecules as ß-glucan, there is a relevant increase in cellular aerobic glycolysis and glutamine metabolism via a central regulatory mechanism of mTOR-HIF1α pathway [32], [33]. Cytokines production after BCG vaccination, illustrated and figured by different studies [34], [35], are represented in increasing Interferon-gamma (IFNγ) and pro-inflammatory cytokines Interleukins IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) as a response to non-mycobacterial stimulation in both infants and adults [22], [30], [36], [37], with higher production in vaccinated females and hence the beneficial effects of BCG is more evident in females [38]. This is remarkable by looking into the percentage of deaths to COVID-19 that was higher in males rather than females. Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes could also be driven by IL-2, IL-12, TNF, and IFN-γ. IFN-γ is secreted by T-cells and Natural-killer (NK) cells and has many roles as antiviral activity, strong regulatory of the-immune response, stimulation of phagocytic bactericidal activity, induction of antigen presentation through major histocompatibility-complex (MHC) molecules, arrangement of leukocyte-endothelium interactions and effects on cell proliferation and apoptosis [39]. IL-8 is crucial in the innate response to bacterial infection by stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis and macrophage triggering [22]. TNF could lead to the activation of beneficial regulatory T cells [30].

For such non-specific mechanisms and evidences, we assume that BCG can be used as an immune modulator to protect against COVID-19 by allocating pulmonary cells under continuous stress which is unfavourable for multiplication of SARS-CoV-2 inside. This strategy will be very helpful in epidemic-control, preventing the spread of infection, limiting the course of the disease and reducing morbidity and mortality rate. This is not the first time to recommend BCG to non-specifically protect or even treat many pathogens other than TB and diseases especially pulmonary diseases. BCG has shown a protective effect against leprosy which is likely due to cross reactivity with mycobacterial antigens [40]. Other studies reinforced the nonspecific effects against leishmania and malaria decreasing their risks and neonatal mortality [41], [42]. Some experimental studies showed that BCG can protect against viral pathogens [41]. BCG was considered as a supplementary treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer by triggering the body's immune system to release cytokines and activating cytotoxic cells to destroy tumour cells after/with transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT) cytotoxic cells [43], [44]. Also, it has a protective effect against other cancers showing an inhibitory effect on tumour growth and was reported to reduce the risk of leukemia and lung cancer [45], [46]. BCG has been reported to prevent lung injury by improving the alveolar surface area which is attributed to the preserved IL-13 expression and up-regulation of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Subunit-1 (NFkB1), Fibroblast growth factor binding protein-1 (FGF.BP1) and Vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) genes [47]. Researchers noticed a decreased rate of allergic asthma in children immunized with the BCG vaccine with the general improvement of lung function through increasing the secretion of T-helper type-1 (Th1) cytokines [48], [49].

Our advice to reallocate BCG for protection against COVID-19 is built on the capability of the BCG vaccine to induce increased cytokine production which will decrease the infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 through antiviral inhibitory cytokines, activated natural-killer cells and activated cytotoxic T-cells. Other studies suggested such correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy at birth and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19 suggesting the induction of trained immunity and consequently protection against SARS-CoV-2 [34], [35], [50].

Another assumption is based on the continuous cytokine production in pulmonary cells after vaccination with BCG [51] will promote pulmonary cells to be more trained and adapted to cytokines for a long time and will be less responsive to side effects of cytokine storm induced by COVID-19 knowing that the cytokine storm is the main cause of respiratory failure and death of COVID-19. [52], [53] The cytokine storm of COVID-19 is a lethal immune condition characterized by activation and proliferation of macrophages, NK cells, T cytotoxic cells and the overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and mediators. The uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory mediators, IL-6, IL-8, IL-1β, and GM-CSF in addition to reactive oxygen species (ROS) could cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) leading to pulmonary fibrosis and death [52]. It worth to mention that there are three established ongoing clinical trials, started in March and April 2020, to address such role of BCG vaccination in protection against COVID-19 especially for healthcare workers and WHO will evaluate the evidence when it is available [54], [55], [56].

On the other hand, in African countries, the number of confirmed cases is considered very low compared to Europe or even China. The highest country with confirmed cases is Egypt with around 10,000 confirmed cases. Malaria disease is considered as a common disease in those countries, as shown in Fig. 1C [57]. They mostly receive malaria treatment e.g. Angola, Benin, and Ethiopia, with their very low number of confirmed cases and death with low mortality rates (Fig. 1D). This finding in countries encountered malaria could be related to the malaria treatment e.g. chloroquine, which has around 50 days half-life [58], and hydroxychloroquine, which have around 40 days half-life [58], that were proven effective against SARS-CoV-2 virus [59]. This long biological half-life could be the reason for such a low number of confirmed cases and worth further investigation. Hydroxychloroquine lowers the pH which can interfere with the replication of the virus through inhibition of lysosomal activity in antigen presenting cells involving B-cells and the plasmacytoid dendritic cells. This will prevent processing of the antigen [60]. In addition to the role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in immunity modulation, also they have an inhibitory effect on two essential steps needed by the new coronavirus to enter the cells, these steps are binding to receptor (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)) and fusion to cell membrane through the interfering with the glycosylation of the receptor [61], [62]. Again, while the full details are not known, the chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine could be recommended for the preventio of SARS-CoV-2 infection [62]. Hydroxychloroquine, also, is likely to attenuate the severe progression of COVID-19, inhibiting the cytokine storm by suppressing T-cell activation. It has a safer clinical profile and is suitable for those who are pregnant and inexpensive and more readily available. [62] However, the side effect of the chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine and any possible interaction should be taken into account [63], [64].

3. Conclusions

BCG vaccine has a very important role in stimulating the immune system but requires time to do so and help in SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention. Antimalarial like chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine has a possible role as prophylactics against SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission and worth further investigation.

We recommend people in countries like Europe and the USA to take BCG vaccine early enough to stimulate their immune systems to help in any possible next winter COVID-19 pandemic occurrence if a proper production of a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 virus was not lunched.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Worldometers.info. 2020 [cited 2020 17 May, 2020]; Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

- 2.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P., Low D. SARS: Systematic Review of Treatment Effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azhar, E.I., et al., Evidence for camel-to-human transmission of MERS coronavirus. 2014. 370(26): p. 2499-2505 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wang L.-F., Eaton B.T. Circumstances and consequences of cross-species transmission. Springer; 2007. Bats civets and the emergence of SARS, in Wildlife and emerging zoonotic diseases: the biology; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization, W.H., Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: implications for IPC precaution recommendations: scientific brief, 27 March 2020, 2020, World Health Organization.

- 6.Morawska Lidia, Cao Junji. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: The world should face the reality. Environ Int. 2020;139:105730. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Yi, Li Xufang, Zhu Bing, Liang Huiying, Fang Chunxiao, Gong Yu, Guo Qiaozhi, Sun Xin, Zhao Danyang, Shen Jun, Zhang Huayan, Liu Hongsheng, Xia Huimin, Tang Jinling, Zhang Kang, Gong Sitang. Characteristics of pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):502–505. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao Fei, Tang Meiwen, Zheng Xiaobin, Liu Ye, Li Xiaofeng, Shan Hong. Evidence for Gastrointestinal Infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1831–1833.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., et al., Clinical progression of patients with COVID-19 in Shanghai, China. 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Huang, C., et al., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. 2020. 395(10223): p. 497-506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Zhou, F., et al., Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Xiao-Wei X. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ: British Med J (Online) 2020:368. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.del Rio Carlos, Malani Preeti N. 2019 Novel Coronavirus—Important Information for Clinicians. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lundgren, F., et al., Vaccination in the prevention of infectious respiratory diseases in adults. 2014. 60(1): p. 4-15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Boman G. The ongoing story of the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(12):1417–1420. doi: 10.1111/apa.13585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwerling A. The BCG World Atlas: a database of global BCG vaccination policies and practices. PLoS Med. 2011:8(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassat Q., Moncunill G., Dobaño C. Making sense of emerging evidence on the non-specific effects of the BCG vaccine on malaria risk and neonatal mortality. BMJ Specialist J. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shann F. Nonspecific effects of vaccines and the reduction of mortality in children. Clinical Therapeut. 2013;35(2):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sørup S. Measles–mumps–rubella vaccination and respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospital contact. Vaccine. 2015;33(1):237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.07.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollm-Delgado M.-G., Stuart E.A., Black R.E. Acute lower respiratory infection among Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG)–vaccinated children. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):e73–e81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Castro M.J., Pardo-Seco J., Martinón-Torres F. Nonspecific (heterologous) protection of neonatal BCG vaccination against hospitalization due to respiratory infection and sepsis. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(11):1611–1619. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freyne B. Neonatal BCG vaccination reduces interferon gamma responsiveness to heterologous pathogens in infants from a randomised controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann, P., A. Finn, and N. Curtis, Does BCG Vaccination Protect Against Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infection? A Systematic Review and. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Stensballe L.G. BCG vaccination at birth and early childhood hospitalisation: a randomised clinical multicentre trial. Arch Dis Childhood. 2017;102(3):224–231. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2016-310760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrager L.K. The status of tuberculosis vaccine development. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30625-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Netea M.G., Quintin J., Van Der Meer J.W. Trained immunity: a memory for innate host defense. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9(5):355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arts R.J. BCG vaccination protects against experimental viral infection in humans through the induction of cytokines associated with trained immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23(1):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.12.010. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Namakula R. Monocytes from neonates and adults have a similar capacity to adapt their cytokine production after previous exposure to BCG and β-glucan. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Netea M.G. Trained immunity: a program of innate immune memory in health and disease. Science. 2016;352(6284) doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1098. p. aaf1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleinnijenhuis J. Bacille Calmette-Guerin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc National Academy Sci. 2012;109(43):17537–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202870109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saeed S. Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science. 2014;345(6204):1251086. doi: 10.1126/science.1251086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng S.-C. mTOR-and HIF-1α–mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science. 2014;345(6204):1250684. doi: 10.1126/science.1250684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arts R.J. Immunometabolic pathways in BCG-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep. 2016;17(10):2562–2571. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Covián C. BCG-induced cross-protection and development of trained immunity. Implication for vaccine design. Front. Immunol. 2019;10:2806. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Covián C. Could BCG vaccination induce protective trained immunity for SARS-CoV-2? Front Immunol. 2020;11:970. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith S.G. Whole blood profiling of bacillus Calmette–Guérin-induced trained innate immunity in infants identifies epidermal growth factor, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor-AB/BB, and natural killer cell activation. Front Immunol. 2017;8:644. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jensen K.J. Heterologous immunological effects of early BCG vaccination in low-birth-weight infants in Guinea-Bissau: a randomized-controlled trial. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(6):956–967. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biering-Sørensen S. Rapid protective effects of early BCG on neonatal mortality among low birth weight boys: observations from randomized trials. J Infect Dis. 2018;217(5):759–766. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boehm U. Cellular responses to interferon-γ. Ann Rev Immunol. 1997;15(1):749–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eisenhut M. BCG vaccination reduces risk of infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis as detected by gamma interferon release assay. Vaccine. 2009;27(44):6116–6120. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moorlag S. Non-specific effects of BCG vaccine on viral infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25(12):1473–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Berendsen M.L. BCG vaccination is associated with reduced malaria prevalence in children under the age of 5 years in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Global Health. 2019;4(6) doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meyer J.P., Persad R., Gillatt D. Use of bacille Calmette-Guérin in superficial bladder cancer. Postgraduate Med J. 2002;78(922):449–454. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kassouf W. Canadian guidelines for treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a focus on intravesical therapy. Canadian Urological Association J. 2010;4(3):168. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.10051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morra M.E. Early vaccination protects against childhood leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16067-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Usher N.T. Association of BCG Vaccination in Childhood With Subsequent Cancer Diagnoses: A 60-Year Follow-up of a Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12014. e1912014 e1912014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Dam A.D. BCG lowers plasma cholesterol levels and delays atherosclerotic lesion progression in mice. Atherosclerosis. 2016;251:6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shirakawa T. The inverse association between tuberculin responses and atopic disorder. Science. 1997;275(5296):77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi I.S., Koh Y.I. Therapeutic effects of BCG vaccination in adult asthmatic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(6):584–591. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61890-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller A. Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID- 19: an epidemiological study. MedRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaveh D.A. Systemic BCG immunization induces persistent lung mucosal multifunctional CD4 TEM cells which expand following virulent mycobacterial challenge. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun X. Cytokine storm intervention in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehta P. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.University, T.A.M. BCG Vaccine for Health Care Workers as Defense Against COVID 19 (BADAS). 2020 18.05.2020]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04348370.

- 55.Institute, M.C.R. BCG Vaccination to Protect Healthcare Workers Against COVID-19 (BRACE). 2020 18.05.2020]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04327206.

- 56.MJM Bonten and U. Utrecht. Reducing Health Care Workers Absenteeism in Covid-19 Pandemic Through BCG Vaccine (BCG-CORONA). 2020 18.05.2020]; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04328441.

- 57.Ricci F. Social implications of malaria and their relationships with poverty. Mediterranean J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4(1) doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2012.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tett S. Bioavailability of hydroxychloroquine tablets in healthy volunteers. British J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27(6):771–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03439.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang, M., et al., Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. 2020. 30(3): p. 269-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Lotteau, V., et al., Intracellular transport of class II MHC molecules directed by invariant chain. 1990. 348(6302): p. 600-605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Vincent, M.J., et al., Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. 2005. 2(1): p. 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Zhou D., Dai S.-M., Tong Q. COVID-19: a recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020 doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lopez-Izquierdo, A., et al., Chloroquine blocks a mutant Kir2. 1 channel responsible for short QT syndrome and normalizes repolarization properties in silico. 2009. 24(3-4): p. 153-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Vereckei, A., et al., Chloroquine cardiotoxicity mimicking connective tissue disease heart involvement. 2013. 35(2): p. 304-306. [DOI] [PubMed]