The emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed tremendous stress on health care systems. While there was early recognition of the need for rapid upscaling and sourcing for ventilatory support, the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) resource planning due to the high incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) was not widely anticipated.

The nephrology division at NewYork-Presbyterian–Columbia University Irving Medical Center responded to this unprecedented surge by undergoing rapid reorganization.1 Several components that constitute care from a nephrology service needed to be tracked in real time, including patient census, equipment (hemodialysis, continuous renal replacement therapy [CRRT]), consumables (CRRT cartridges and solutions, vascular access kits, dialysis filters), and staffing (providers, nurses, and dialysis technicians). Data-driven tools to facilitate this reorganization became integral to ensure the safe and equitable delivery of our services. To this end, we developed 3 novel tools: (i) a Patient Census Tracker and Dashboard, (ii) a CRRT Sharing Protocol Tracker and Dashboard, and (iii) a Therapy-Fluid Conservation Nomogram. Given the potential benefit that these tools could have for nephrology programs faced with similar challenges, we are making these tools open source, along with a brief description, to allow other institutions to adopt and leverage these tools for their own services.

Patient Census Tracker and Dashboard

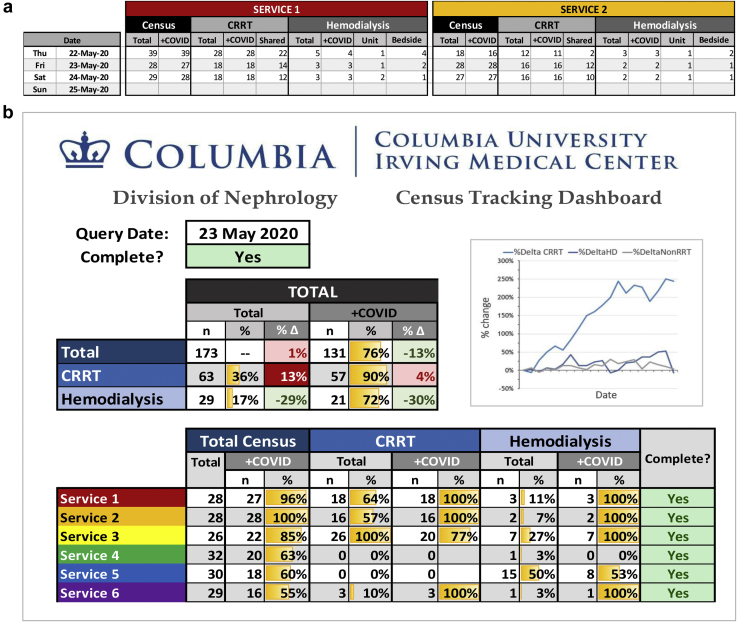

With the surge in COVID-19 admissions came a significant increase in incident nephrology consults and growth of our consult censuses.1 Resource planning required the ability to track patient censuses in real time to ensure patients were evenly distributed. The high incidence and mortality among patients with acute kidney injury requiring RRT, coupled with the expansion of nontraditional intensive care unit (ICU) spaces, created substantial turnover and movement, making it a challenge to track patient volumes. We developed the Patient Census Tracker (Figure 1a) that analyzed our individual consult service censuses, broken down by COVID 19 status and RRT needs. This allowed for early identification of individual services with large volumes and prompted the addition of services and led to a reorganization of our services based largely on ICU location within the hospital. The Patient Census Tracker Dashboard (Figure 1b) collated the data and provided a snapshot of each service with a breakdown by COVID-19 status and RRT needs. This dashboard informed a daily response review with precise data of census growth and projected resource needs.

Figure 1.

(a) Patient Census Tracker and (b) Dashboard. (a) Each nephrology service (2 of the 6 services shown as an example) reported daily census counts by coronavirus disease (COVID) status and renal replacement therapy (RRT) needs. (b) This populated a division-wide dashboard that summarized the entire divisional service size stratified by COVID status and RRT needs and displays historical growth trends visually by cell color shading and graphically over time. HD, hemodialysis.

CRRT Sharing Protocol Tracker and Dashboard

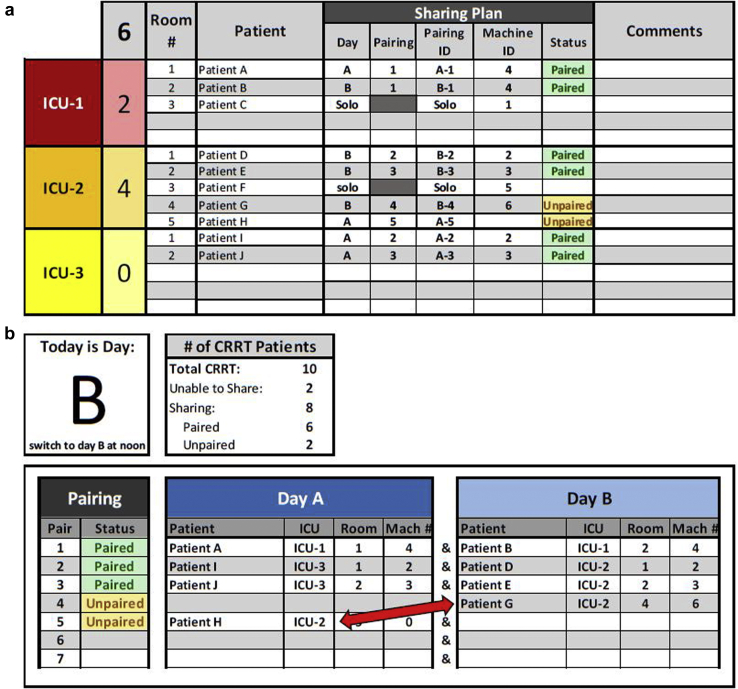

At the height of the surge, the increased demand for acute dialytic therapies overwhelmed the available CRRT resources in New York City.2 To meet these needs, we adapted our CRRT program, and CRRT machines became a shared resource among patients to ensure adequate renal support.3, 4, 5, 6, 7 When clinically feasible, CRRT schedules were converted to a 24 hours on–24 hours off shared model (actual therapy time per shift was approximately 22 of 48 hours, accounting for 2 hours of downtime associated with cleaning the machine, moving it to a new location, and priming it for the next patient) (Figure 2). Dialysate flow rates were adjusted to account for this accelerated therapy model (Figure 3). This approach lowered the cartridge utilization rate compared with that of a 12-hour protocol and also minimized nursing burden and machine downtime associated with cleaning, moving, and repriming the machines. This sharing protocol, however, presented a logistical challenge given the size of our CRRT program (67 patients at the height of the surge).1 Pairings changed due to fluctuating clinical needs of the patients, movement of patients across geographically distant ICUs, renal recovery, and death. We instituted a daily RRT huddle with attending physicians and fellows on our ICU consult services to review RRT needs and available resources to ensure appropriate allocation of resources. The complexity of the task given the patient volume and logistical challenges required us to develop the CRRT Sharing Protocol Tracker and Dashboard (Figure 2) to facilitate the most efficient pairing between patients across different services and ICUs.

Figure 2.

Continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) Sharing Protocol Tracker and dashboard. (a) Patients were identified as able to tolerate a sharing protocol (alternating days A and B) or not (solo) by broken down by each intensive care unit (ICU) location. Patients who were unpaired or resources that were overallocated based on their pairing and machine number were visually identified by a color change and allowed clinicians to accurately pair these patients. (b) This information populates the CRRT Sharing Dashboard that detailed names, ICU location, room number, and machine (Mach) number of the 2 patients in a pair, and this information guided coordinators in charge of physically moving the machine from one patient to the next. The dashboard allowed for rapid visual identification of pairing opportunities (e.g. patient G and patient H in ICU-2 can be paired as they are on alternating days [red arrow]).

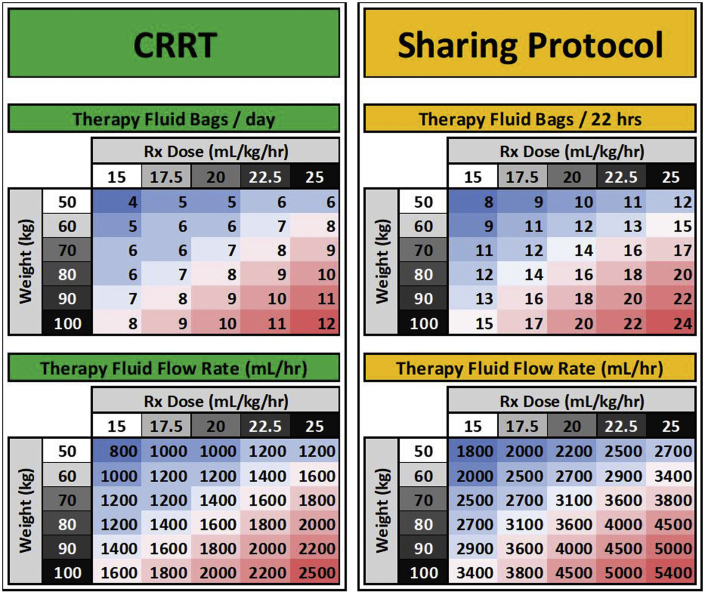

Figure 3.

Therapy Fluid Conservation Nomogram. For a given patient weight and prescribed dose, a total therapy fluid volume required session was calculated and rounded up to a 5-L increment (5-L therapy fluid bags). Flow rates for patients on this sharing protocol were determined by adjusting for a 22-hour period. The projected total delivered therapy volume for a standard 48-hour period was adjusted for a 22-hour delivery period (standard flow rates multiplied by 2.18 []) and rounding down to the nearest dl/h. This prevented partially used therapy fluid bags from being discarded at the end of a 22-hour treatment session.

The huddle identified RRT needs for the day by modality—CRRT, intermittent hemodialysis or acute peritoneal dialysis. For patients requiring CRRT, providers confirmed their current status (on or off CRRT) and whether each patient needed to continue on the current schedule or the schedule needed to be modifies. Given the alternating day CRRT schedule, each day was designated as either A or B and patients sharing machines were balanced between the 2 days. Machines were assigned a numerical code that was linked to their radiofrequency identification to track their movement and location throughout the hospital. Each patient was assigned a potential pairing and machine number that allowed the tool to identify whether each patient was unpaired, paired, or inappropriately allocated (e.g., 3 patients to the same machine) (Figure 2a). The number of patients requiring CRRT for that specific day was totaled and then subtotaled by ICU location. This pairing information fed into the CRRT Sharing Protocol Dashboard (Figure 2b), which detailed names, ICU location, room number, and machine number of the 2 patients in a pair and guided coordinators in charge of physically moving the machine from one patient to the next after the huddle. It also allowed for pairing of patients based on geography and to make more efficient pairs as the census was very dynamic (see Figure 2b for examples). Such a system allowed for hour-by-hour changes to be centralized and tracked, and it facilitated resource allocation and allowed us to maximize the number of patients this life-saving resource was available to.1

Therapy Fluid Conservation Nomogram

While the CRRT sharing protocol allowed us to maximize the number of treated patients, it did not address the therapy fluid (dialysate and replacement fluid) shortage. The rapid rise in patients requiring CRRT both in New York City and across the country led to projected national shortages. With traditional CRRT prescriptions, the number of wasted bags from partial use was minimal, however, with the sharing protocol any partially used bags at the end of the 22-hour session were discarded. To minimize this waste, we developed the Therapy-Fluid Conservation Nomogram (Figure 3) to assist providers in standardizing the default dialysate flow rates for continuous venovenous hemodialysis (use of the Sharing Protocol and Therapy-Fluid Conservation Nomogram were developed primarily for use in continuous venovenous hemodialysis and use with other modalities should be adapted for each institution depending on their blood flow rates and use of pre- and postfilter dilution for convective modalities). For a given patient’s weight and prescribed dose, a total therapy volume required per session was calculated and rounded up to a 5 L–bag increment, and this number was indicated in the CRRT order to avoid hanging unnecessary bags at the beginning of the treatment session. Flow rates for patients on this sharing protocol were determined by adjusting for a 22-hour period. Standardizing flow rates allowed nurses to hang a prescribed number of bags per patient per day and prevented wasting partially used bags at the end of a session, allowing us to extend our vulnerable therapy fluid supply. For example, at the peak of the surge, even 1 partially used bag per patient on the shared protocol per day would have resulted in up to 20 bags (100 l) of therapy fluid wasted per day. Standardizing the number of bags and flow rates in chart form also allowed us to alter the default therapy fluid rates depending on the projected number of days of supply when clinically safe to do so.

Conclusion

The unprecedented surge of nephrology inpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City required us to develop novel census- and supply-tracking and forecasting tools. These tools allowed us to stay informed about the availability of resources and our supply chain to ensure that patients in need of RRT had access to this form of life support. Our tools allowed for an organized, data-driven divisional response and facilitated the planning necessary for rapid reorganization of nephrology services within our institution. While these tools still rely on manual entry rather than an automatic feed from an electronic health record, it required minimal entry time for any given provider as each service was responsible for updating the census for their own service. These tools are complex enough to deal with the challenges of a large program such as ours, but they are also easily adaptable for smaller nephrology programs and we have made these tools available for general use given their adaptability and potential to benefit consultative services at other institutions.

These tools are be available through Academic Commons at Columbia University: Census Tracking Tracker and Dashboard, https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-kja6-k736; CRRT Sharing Protocol Tracker and Dashboard, https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-8619-gn42.

Disclosure

All the authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NewYork-Presbyterian COVID-19 RRT Task Force Members, Columbia University Division of Nephrology Faculty, and Iman Ghavami and Vanna Nicasio who helped track and coordinate CRRT machines at Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

References

- 1.The Division of Nephrology, Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians Working Group Disaster response to the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with kidney disease in New York City. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1371–1379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abelson R., Fink S., Kulish N., Thomas K. An overlooked, possibly fatal coronavirus crisis: a dire need for kidney dialysis. New York Times. April 18, 2020 Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/18/health/kidney-dialysis-coronavirus.html. Accessed June 2, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edrees F., Li T., Vijayan A. Prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23:195–202. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellomo R., Baldwin I., Fealy N. Prolonged intermittent renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Resusc. 2002;4:281–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gashti C.N., Salcedo S., Robinson V., Rodby R.A. Accelerated venovenous hemofiltration: early technical and clinical experience. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51:804–810. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allegretti A.S., Endres P., Parris T. Accelerated venovenous hemofiltration as a transitional renal replacement therapy in the intensive care unit. Am J Nephrol. 2020;51:318–326. doi: 10.1159/000506412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marshall M.R., Creamer J.M., Foster M. Mortality rate comparison after switching from continuous to prolonged intermittent renal replacement for acute kidney injury in three intensive care units from different countries. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:2169–2175. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]