Abstract

This survey study compared the level of integration between National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated and non–NCI designated cancer centers.

Timely integration of specialist palliative care (PC) to oncologic care is associated with improved patient outcomes.1 Although several studies have examined supportive and palliative care services at US cancer centers,2,3 none to our knowledge have assessed the level of integration using a standardized set of indicators. In this study, we compared the level of integration between National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated and non–NCI-designated cancer centers.

Methods

This is a preplanned analysis of a national survey to assess the structure, processes, and outcomes of the PC programs at US cancer centers.4 The study protocol was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and granted exemption status as a minimal-risk study that did not require patient data. Between April and August 2018, we surveyed the PC program leaders of all 62 NCI-designated cancer centers and a randomly selected sample of 62 of 1252 non–NCI-designated cancer centers (using RAND() in Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2013 [Microsoft Corporation]) in the Commission on Cancer National Cancer Database. Among these centers, 61 NCI-designated cancer centers and 38 non–NCI-designated cancer centers had a PC program, and the PC program leaders were invited to participate.4 The survey included 13 integration indicators derived from international consensus to assess program structure (Nos. 1-3), processes (Nos. 4-6), outcomes (Nos. 7-9), and education (Nos. 10-13) (Table).5

Table. Individual Integration Indicators for National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Designated and Non–NCI-Designated Cancer Centers.

| Variable | NCI-designated cancer centers, No. (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Characteristic | |||

| Palliative care program available, No./Total (%) | 61/62 (98) | 38/62 (61) | <.001 |

| Response rate | 52/61 (85) | 27/38 (71) | .12 |

| Duration of palliative care program, y | |||

| <1 | 3 (6) | 4 (15) | .04 |

| 1-2 | 0 | 2 (7) | |

| 3-5 | 4 (8) | 4 (15) | |

| >5 | 45 (87) | 17 (63) | |

| No. of full-time equivalent physician positions, median (IQR) | 4 (2.7-7.1) | 1 (1.0-3.0) | <.001 |

| Integration indicators | |||

| 1. Presence of palliative care inpatient consultation team | 50 (96) | 24 (89) | .33 |

| 2. Presence of palliative care outpatient clinic | 51 (98) | 17 (63) | <.001 |

| 3. Presence of interdisciplinary palliative care teamb | 46 (92) | 18 (67) | .009 |

| 4. Routine symptoms screening | 38 (76) | 13 (72) | >.99 |

| 5. Early referral to palliative carec | 9 (69) | 0 | .14 |

| 6. Proportion of routine documentation of advance care plan, median (IQR) | 25 (15-40) | 40 (20-60) | .06 |

| 7. Proportion of outpatients with pain assessed before death, median (IQR) | 100 (85-100) | 100 (100-100) | .16 |

| 8. Proportion of patients with 2 or more emergency department visits in last 30 d of life, median (IQR) | 25 (20-60) | 50 (50-80) | .06 |

| 9. Proportion of place of death consistent with patient’s preference, median (IQR) | 50 (50-75) | 50 (50-75) | .97 |

| 10. Didactic palliative care curriculum for oncology fellows provided by palliative care specialists | 37 (77) | 6 (27) | <.001 |

| 11. Continuing education in palliative care | 15 (30) | 7 (32) | >.99 |

| 12. Combined palliative care and oncology educational activities | 19 (39) | 4 (18) | .11 |

| 13. Routine rotation in palliative care for oncology fellows | 26 (55) | 3 (25) | .10 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

We compared NCI-designated and non–NCI-designated cancer centers using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

Defined as at least 1 physician, 1 nurse, and 1 psychosocial team member, such as psychologist/counselor, chaplain, or social worker.

Defined as median interval of ≥6 months between referral to outpatient palliative care to death.

Two Palliative Care and Oncology Integration Indexes (PCOIs) were computed: PCOI-9 included 9 indicators (Nos. 1-5 and 10-13), and PCOI-13 included all 13 indicators. These indexes had previously been evaluated for face validity, content validity, and ability to discriminate between groups.5,6 Scores were prorated if at least 50% of the variables were available. A higher score indicates greater integration.6 We compared NCI-designated and non–NCI-designated centers using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. As part of the sensitivity analysis, we computed the PCOI scores using the worst-case scenario, in which missing variables were assigned a score of 0. We examined the association between PCOI scores and center characteristics with the Spearman correlation test using SPSS, version 24.0 (IBM). All tests were 2-sided and a P value of .05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

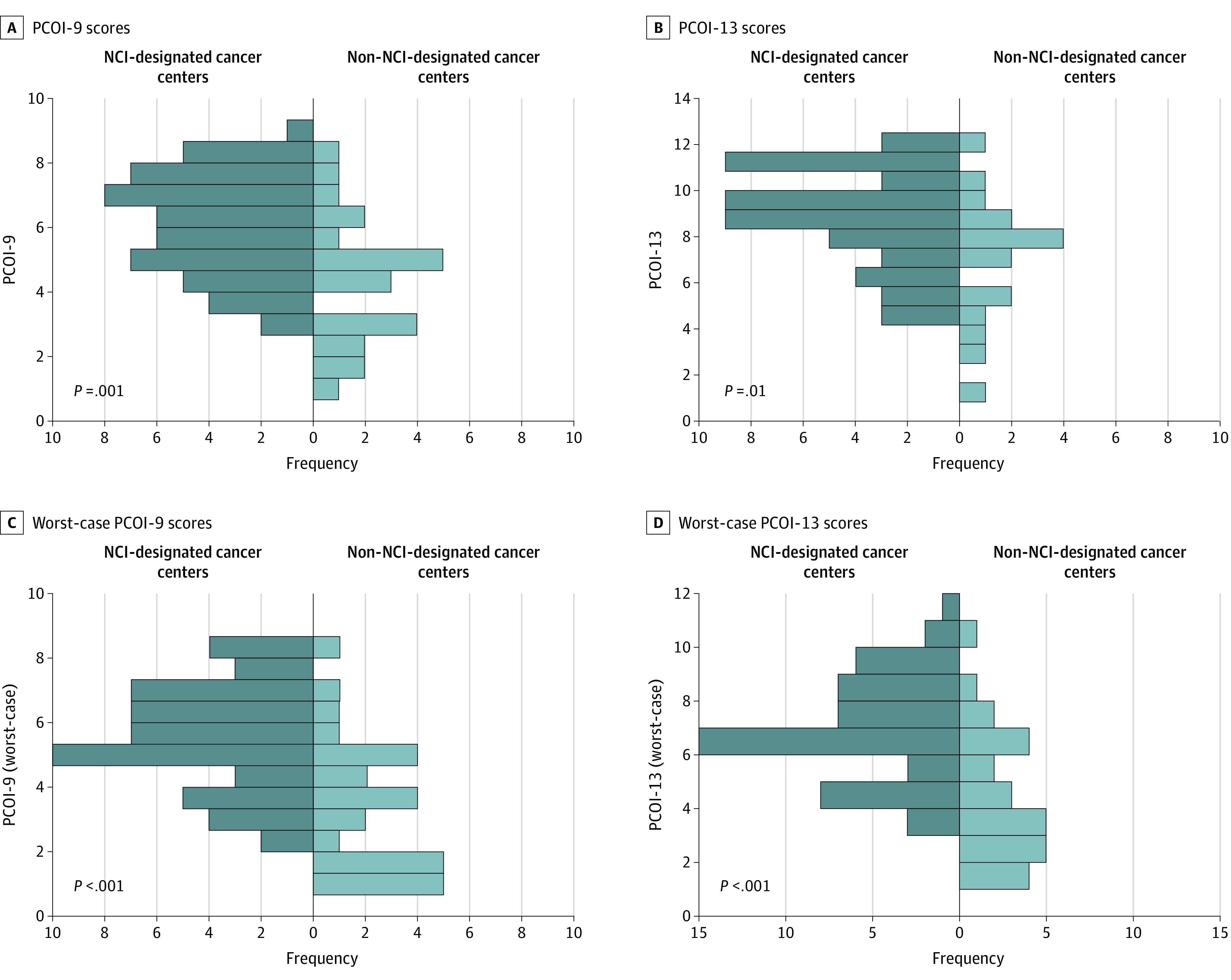

The response rate was 52 of 61 (85%) for NCI-designated cancer centers and 27 of 38 (71%) for non–NCI-designated cancer centers. Both the median PCOI-9 and PCOI-13 scores were significantly higher among NCI-designated than non–NCI-designated cancer centers (Figure, A and B). Similar findings were found with worst-case scenario analyses (Figure, C and D). Higher PCOI scores were associated with longer PC program operation duration (PCOI-9: ρ, 0.34; P = .003; PCOI-13: ρ, 0.35; P = .003) and greater number of full-time equivalent physicians (PCOI-9: ρ, 0.43; P < .001; PCOI-13: ρ, 0.42; P < .001).

Figure. Distribution of Palliative Care and Oncology Integration Index (PCOI) Scores by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Designation.

Two PCOI scores were computed according to previously established procedures: PCOI-9 included indicators Nos. 1-5 and 10-13, and PCOI-13 included all 13 indicators.6 We assigned 1 point for an affirmative response for questions with a dichotomized response (all except Nos. 6-9), and a score between 0 and 1 based on the proportions for questions with a continuous variable as response (ie, questions Nos. 6-9 [eg, 63% = 0.63]; except for question 8, which was reverse scored [eg, 63% = 0.37]). The total scores were prorated if at least 50% of variables were available. We also computed the PCOI scores using the worst-case scenario, in which missing variables were assigned a score of 0. The total scores ranged from 0-9 points for the PCOI-9 and 0-13 points for the PCOI-13, with a higher score indicating a greater degree of integration. The NCI-designated cancer centers were significantly more integrated than non–NCI-designated cancer centers based on PCOI-9 scores (median [interquartile range {IQR}], 6.1 [5.1-7.4] vs 4.5 [3.0-6.0]; P = .001) (A); PCOI-13 scores (median [IQR], 8.8 [7.4-10.7] vs 7.7 [5.2-8.5]; P = .01) (B); PCOI-9 scores (worst case) (median [IQR], 6 [4.3-6.9] vs 3.6 [2.0-5.1], P < .001) (C); and PCOI-13 scores (worst case) (median [IQR], 6.3 [5.4-8.2] vs 3.7 [2.0-6.1]; P < .001) (D).

The Table shows the individual indicators. Although inpatient PC service was mostly available in both groups, NCI-designated centers were significantly more likely to have outpatient clinics, interdisciplinary teams, didactic PC lectures, and mandatory rotations for oncology fellows than non–NCI-designated cancer centers. Advance care planning was limited in both cohorts.

Discussion

The NCI-designated cancer centers had more integrated PC services than the non–NCI-designated centers, likely because they had greater resources, staffing, and academic infrastructure. Given that more than 80% of patients with cancer are treated at non–NCI-designated centers, our findings highlight the need to further develop PC at these institutions. The NCI-designated centers may serve as models of integration.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size; self-reported data; missing data in some variables, such as timing of referral and center outcomes; and lack of adjustment of potential confounders, such as hospital size and resources. A study of European Society for Medical Oncology–designated cancer centers found that nontertiary care hospitals were more integrated than tertiary care hospitals, suggesting that smaller size may be advantageous.6

At the system level, systematic assessment of PCOI scores may facilitate benchmarking, comparisons over time, and setting standards for accreditation and recognition programs. At the institution level, PCOI scores may help to set goals and allocate resources for quality improvement initiatives. An individualized report card may be helpful. Advance care planning and education represent 2 key areas for further improvement.

References

- 1.Sullivan DR, Chan B, Lapidus JA, et al. . Association of early palliative care use with survival and place of death among patients with advanced lung cancer receiving care in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(12):1702-1709. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.3105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer SL, Clark K, Grant M, Loscalzo MJ. Seventeen years of progress for supportive care services: a resurvey of National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(4):917-925. doi: 10.1017/S1478951514000601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. . Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1054-1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui D, De La Rosa A, Chen J, et al. . State of palliative care services at US cancer centers: an updated national survey. Cancer. 2020;126(9):2013-2023. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, et al. . Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):e552-e559. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30577-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D, Cherny NI, Wu J, Liu D, Latino NJ, Strasser F. Indicators of integration at ESMO Designated Centres of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care. ESMO Open. 2018;3(5):e000372. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]