Abstract

Introduction

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process and inflammation is an important component of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) is a useful parameter showing the degree of the inflammatory response.

Aim

To explore the association between PLR and long-term mortality in patients with ACS.

Material and methods

A total of 538 patients who had a diagnosis of ACS between January 2012 and August 2013 were followed up to 60 months. On admission, blood sampling to calculate PLR and detailed clinical data were obtained.

Results

In total, 538 patients with a mean age of 61.5 ±13.1 years (69% male) were enrolled in the study. Median follow-up was 79 months (IQR: 74–83 months). Patients were divided into 3 tertiles based on PLR levels. Five-year mortality of the patients was significantly higher among patients in the upper PLR tertile when compared with the lower and middle PLR tertile groups (55 (30.7%) vs. 27 (15.0%) and 34 (19.0%); p < 0.001, p = 0.010 respectively). In the Cox regression analysis, a high level of PLR was an independent predictor of 5-year mortality (OR = 1.005, 95% CI: 1.001–1.008, p = 0.004). Kaplan-Meier analysis according to the long-term mortality-free survival revealed the higher occurrence of mortality in the third PLR tertile group compared to the first (p < 0.001) and second tertiles (p = 0.009).

Conclusions

PLR, which is an easily calculated and universally available marker, may be useful in long-term risk classification of patients presenting with ACS.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, acute coronary syndrome, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, long-term mortality

Summary

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), derived from platelet and lymphocyte counts, is a useful parameter showing the degree of the inflammatory response. We evaluated the effect of PLR on long-term mortality in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Patients were divided into 3 tertiles based on PLR levels. Five-year mortality of the patients was significantly higher among patients in the upper PLR tertile when compared with the lower and middle PLR tertile groups. Different from other inflammatory markers, PLR is an inexpensive and readily available biomarker that may be useful for long-term cardiac risk stratification in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD), the leading cause of death and disability in the world, caused more than 8 million deaths worldwide in 2013 [1]. Although the mortality rate for this condition has gradually decreased in recent decades in western countries, still one-third of deaths in people over 35 years are caused by coronary heart disease [2, 3]. Almost half of deaths due to coronary heart disease occur after an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Patients with ACS present with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris [4].

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process and inflammation is an important component of ACS [5, 6]. Platelets play an important role in the pathophysiology of ACS. Platelets release thromboxanes and other mediators, which may lead to increased inflammation in patients with high platelets. Together with fibrin, platelets form a coronary thrombus [7, 8]. Low blood lymphocyte count has been shown to be associated with poor cardiovascular outcomes in coronary artery disease (CAD) [9, 10]. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), derived from these values, is a useful parameter showing the degree of the inflammatory response, which is used as an important prognostic factor in many cardiovascular diseases [11–15]. In our previous study, we showed that high PLR levels in patients with ACS increase in-hospital mortality [12].

Aim

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate the relationship between PLR level and long-term mortality in patients with ACS.

Material and methods

Study population

This is an observational, single-center study. We retrospectively collected patients with ACS undergoing coronary angiography between January 2012 and August 2013. We excluded patients with hematological disease, cardiogenic shock, systemic inflammatory disease or active infection, significant valvular heart disease, malignancy, severe liver or renal disease and autoimmune disease. The local ethics committee approved the study.

Definitions

Acute coronary syndrome was defined as presentation with symptoms of ischemia in association with electrocardiographic changes or positive cardiac biomarkers [4]. We categorized ACS into three categories: ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina pectoris (USAP). The diagnosis of STEMI was established when the patient had symptoms of ACS lasting ≥ 30 min and accompanied by > 1 mm (0.1 mV) ST-segment elevation in ≥ 2 contiguous leads on ECG which was later confirmed by increase in cardiac biomarkers. The diagnosis of NSTEMI was established if the characteristic anginal chest pain lasted ≥ 20 min with or without associated ST-segment depression ≥ 0.1 mV and/or T-wave inversion in 2 contiguous leads on ECG or no electrocardiographic abnormalities and the presence of increase in serum cardiac biomarker levels. USAP was defined as clinical and electrocardiographic changes in NSTEMI not accompanying an increase in serum cardiac biomarker levels. Arterial hypertension was considered in patients with repeated blood pressure measurements > 140/90 mm Hg or active use of antihypertensive drugs. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a fasting plasma glucose level more than 126 mg/dl in multiple measurements or active use of antidiabetic medications. Smoking was defined as current smoking. Patients having fever or symptoms or signs of urinary tract or respiratory system infection (leukocytosis or nitrite positivity in urine, infiltration in chest X-ray) were defined as having active infection. The PLR was calculated as the ratio of platelet count to lymphocyte count.

Biochemical and hematological parameters

Peripheral venous blood samples were drawn on admission to the emergency room. Total and differential leukocyte counts were measured by an automated hematology analyzer (Abbott Cell-Dyn 3700; Abbott Laboratory, Abbott Park, Illinois, USA). Routine biochemical tests were performed by standard techniques.

Follow-up

This period was defined as the time interval between index admission to the emergency room and all-cause death or last clinical visit. Based on the routine follow-up program applied in our center, clinical visits were scheduled at 1-month intervals in the first 3 months of admission, 3-month intervals in the first year and 6-month intervals in the following years. Since all patients were diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome, they received dual antiplatelet therapy for the first year regardless of interventional or surgical treatment, and then they were planned to continue with single antiplatelet therapy. In addition, all patients were routinely treated with statin. In addition, β-blocker, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and spironolactone therapy was started for patients with additional diseases such as heart failure and hypertension. After discharge from the hospital, all survived patients were followed up regarding “5-year all-cause mortality” via routine clinical visits, hospital death chart records, telephone calls and death charts of the Turkish National Population Register. During 5-year follow-up, medical records of 538 out of 587 patients were reached.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed with SPSS software, version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to verify the normality of the distribution of continuous variables. Continuous variables were defined as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range); categorical variables were given as percentages. Comparison among multiple groups was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or Kruskal-Wallis test, and the χ2 or Fisher exact test was carried out for categorical variables as appropriate. For the post-hoc analysis, either the Scheffe or Mann-Whitney U test was performed. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Variables for which the p-value was < 0.25 in the univariate analysis were assessed by Cox regression analysis to evaluate the independent predictors of 5-year mortality. All variables found to be significant in the univariate analysis were included in the Cox regression model, and the results are shown as the odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Survival rates between PLR tertiles were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. A value of p < 0.05 (2-sided) was considered as statistically significant.

Results

In total, 538 patients with a mean age of 61.5 ±13.1 years (69% male) were enrolled in the study. Median follow-up was 79 months (IQR: 74–83 months). Patients were divided into 3 tertiles based on PLR levels: 83.7 ±14.5 in tertile 1, 125.2 ±13.2 in tertile 2, and 203.3 ±43.7 in tertile 3. According to the PLR tertiles, the baseline demographic, hematological, and angiographic parameters of the patients are shown in Table I.

Table I.

Clinical, hematologic, and angiographic characteristics of population with acute coronary syndrome according to platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio tertiles

| Variables | PLR | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertile 183.7 ±14.5 (n = 180) |

Tertile 2125.2 ±13.2 (n = 179) |

Tertile 3203.3 ±43.7 (n = 179) |

||

| Age [years] | 59.2 ±12.3 | 61.4 ±12.5 | 63.9 ±13.7 | 0.003a |

| Male gender, n (%) | 131 (72.8) | 123 (68.7) | 120 (67) | 0.478 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 78 (43.3) | 74 (41.3) | 93 (52.0) | 0.100 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 37 (20.6) | 48 (26.8) | 53 (29.6) | 0.132 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 82 (45.6) | 75 (41.9) | 69 (38.5) | 0.404 |

| Previous MI history, n (%) | 22 (12.2) | 32 (17.9) | 23 (12.8) | 0.246 |

| Hemoglobin [g/dl] | 14.1 ±1.4 | 13.9 ±1.6 | 13.6 ±1.7 | 0.015b |

| White blood cell count [103/μl] | 11.6 ±3.3 | 11.4 ±3.5 | 11.8 ±3.7 | 0.547 |

| Neutrophil count [103/μl] | 7.8 ±3.1 | 8.5 ±3.3 | 9.6 ±3.6 | < 0.001c |

| Lymphocyte count [103/μl] | 2.8 ±0.8 | 2.1 ±0.5 | 1.5 ±0.5 | < 0.001d |

| Platelet count [103/μl] | 228.1 ±53.9 | 253.7 ±52.5 | 285.2 ±65.6 | < 0.001e |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] | 0.80 (0.72–0.97) | 0.80 (0.70–0.96) | 0.83 (0.72–1.00) | 0.449 |

| CRP [mg/dl] | 0.52 (0.30–0.97) | 0.59 (0.34–0.99) | 0.63 (0.38–1.13) | 0.452 |

| Total cholesterol [mg/dl] | 177.6 ±39.7 | 181.9 ±44.8 | 174.5 ±37.9 | 0.226 |

| Triglyceride [mg/dl] | 135 (90–205) | 135 (92–195) | 120 (80–176) | 0.031f |

| LDL [mg/dl] | 109.8 ±31.6 | 113.9 ±37.2 | 111.1 ±31.7 | 0.504 |

| HDL [mg/dl] | 34.5 ±8.2 | 36.3 ±9.7 | 35.4 ±10.0 | 0.179 |

| Left ventricular EF (%) | 50 (45–55) | 48 (40–55) | 45 (40–50) | 0.004g |

| Patients who underwent PCI | 146 (81.1) | 153 (85.5) | 160 (89.4) | 0.086 |

| Patients who underwent CABG | 18 (10) | 25 (14) | 33 (18.4) | 0.072 |

| Number of stenosed coronary arteries, n (%): | 0.914 | |||

| Single vessel | 75 (41.7) | 77 (43.0) | 73 (40.8) | |

| Two vessels | 61 (33.9) | 53 (29.6) | 58 (32.4) | |

| Three vessels | 44 (24.4) | 49 (27.4) | 48 (26.8) | |

| Type of acute coronary syndrome, n (%): | 0.002 | |||

| USAP | 24 (13.3) | 16 (8.9) | 19 (10.6) | |

| NSTEMI | 65 (36.1) | 53 (29.6) | 34 (19.0) | |

| STEMI | 91 (50.6) | 110 (61.5) | 126 (70.4) | |

| Culprit vessel, n (%): | 0.585 | |||

| LAD | 75 (41.7) | 82 (45.8) | 84 (46.9) | |

| Cx | 52 (28.9) | 51 (28.5) | 41 (22.9) | |

| RCA | 53 (29.4) | 46 (25.7) | 54 (30.2) | |

| Long-term mortality, n (%): | ||||

| 1 year | 11 (6.1) | 21 (11.7) | 35 (19.6) | 0.001 |

| 3 years | 18 (10.0) | 29 (16.2) | 50 (27.9) | < 0.001 |

| 5 years | 27 (15.0) | 34 (19.0) | 55 (30.7) | 0.001 |

Data are presented as number (percentage) and mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) values. For post hoc analysis either Scheffe or Mann-Whitney U test was performed. *ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests:

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p = 0.254, p = 0.003, and p = 0.192, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p = 0.567, p = 0.017, and p = 0.197, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p = 0.143, p < 0.001, and p = 0.010, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p = 0.788, p = 0.026, and p = 0.020, respectively

1 vs. 2, 1 vs. 3, and 2 vs. 3 p = 0.091, p = 0.001, and p = 0.162, respectively.

CRP – C-reactive protein, Cx – circumflex, EF – ejection fraction, HDL – high-density lipoprotein, LAD – left anterior descending, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, MI – myocardial infarction, NLR – neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NSTEMI – non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, RCA – right coronary artery, STEMI – ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, USAP – unstable angina pectoris. CRP values were available for 225 patients.

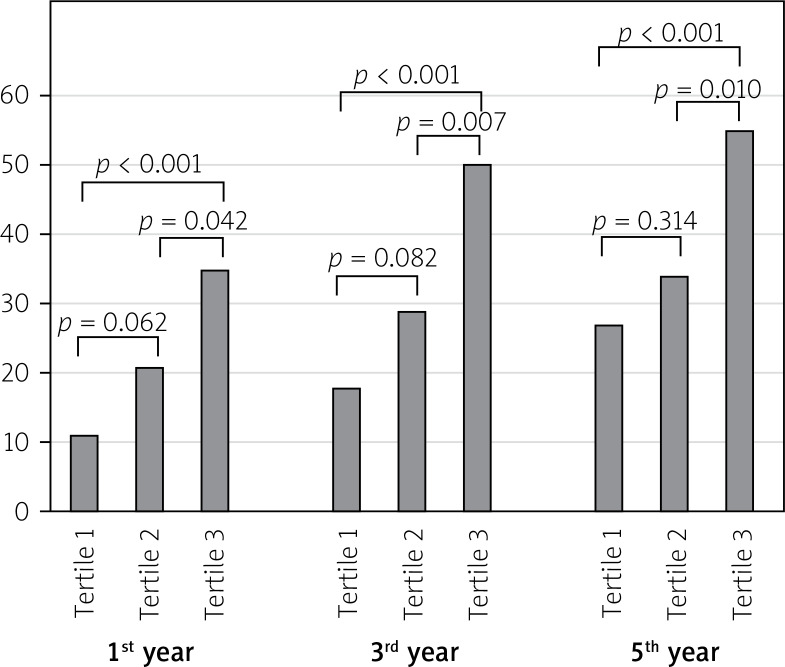

One-year mortality of the patients was significantly higher among patients in the upper PLR tertile when compared with the lower and middle PLR tertile groups (35 (19.6%) vs. 11 (6.1%) and 21 (11.7%); p < 0.001, p = 0.042 respectively; Figure 1). Three-year mortality of the patients was significantly higher among patients in the upper PLR tertile when compared with the lower and middle PLR tertile groups (50 (27.9%) vs. 18 (10.0%) and 29 (16.2%); p < 0.001, p = 0.007 respectively; Figure 1). Five-year mortality of the patients was significantly higher among patients in the upper PLR tertile when compared with the lower and middle PLR tertile groups (55 (30.7%) vs. 27 (15.0%) and 34 (19.0%); p < 0.001, p = 0.010 respectively; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

One-, three- and five-year mortality comparisons of PLR tertile groups

In univariate and Cox regression analysis, independent predictors of long-term-mortality (Table II) were assessed. The variables whose p-value < 0.25 in univariate analysis were specified as potential risk factors and included in the Cox regression analysis. In the Cox regression analysis, a high level of PLR was an independent predictor of 5-year mortality (OR = 1.005, 95% CI: 1.001–1.008, p = 0.004), together with age (OR = 1.049, 95% CI: 1.029–1.069, p < 0.001), female gender (OR = 1.679, 95% CI: 1.058–2.666, p = 0.028), left ventricular EF (OR = 0.963, 95% CI: 0.942–0.984, p < 0.001), multivessel disease (OR = 1.993, 95% CI: 1.205–3.297, p = 0.007), previous MI history (OR = 1.730, 95% CI: 1.012–2.955, p = 0.045), reticulocyte distribution width (RDW) (OR = 1.148, 95% CI: 1.005–1.312, p = 0.043), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (OR = 0.975, 95% CI: 0.955–0.995, p = 0.015) and creatinine (OR = 1.827, 95% CI: 1.359–2.456, p < 0.001; Table II).

Table II.

Significant predictors of five-year mortality in univariable and Cox regression analyses

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | Cox regression analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age | 1.083 (1.061–1.106) | < 0.001 | 1.049 (1.029–1.069) | < 0.001 |

| Female gender | 2.146 (1.402–3.283) | < 0.001 | 1.679 (1.058–2.666) | 0.028 |

| Left ventricular EF | 0.939 (0.918–0.960) | <0.001 | 0.963 (0.942–0.984) | 0.001 |

| PLR | 1.008 (1.005–1.012) | < 0.001 | 1.005 (1.001–1.008) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 2.844 (1.851–4.370) | < 0.001 | 1.171 (0.744–1.843) | 0.496 |

| LAD as the infarct-related artery | 1.095 (0.725–1.653) | 0.668 | ||

| STEMI as the cause of ACS | 0.778 (0.513–1.180) | 0.238 | 1.264 (0.578–2.764) | 0.557 |

| Non-STEMI as the cause of ACS | 1.610 (1.040–2.491) | 0.033 | 1.301 (0.622–2.721) | 0.485 |

| Multivessel disease | 4.233 (2.543–7.048) | < 0.001 | 1.993 (1.205–3.297) | 0.007 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.652 (1.058–2.582) | 0.027 | 1.219 (0.793–1.873) | 0.367 |

| Smoking | 1.497 (0.976–2.298) | 0.065 | 1.194 (0.757–1.884) | 0.446 |

| Previous MI history | 4.784 (2.876–7.958) | < 0.001 | 1.730 (1.012–2.955) | 0.045 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.788 (0.691–0.899) | < 0.001 | 1.120 (0.988–1.271) | 0.076 |

| White blood cell | 1.048 (0.989–1.110) | 0.111 | ||

| RDW | 1.307 (1.114–1.534) | 0.001 | 1.148 (1.005–1.312) | 0.043 |

| Creatinine | 18.877 (7.854–45.367) | < 0.001 | 1.827 (1.359–2.456) | < 0.001 |

| LDL | 0.997 (0.990–1.003) | 0.307 | ||

| HDL | 0.984 (0.962–1.007) | 0.174 | 0.975 (0.955–0.995) | 0.015 |

ACS – acute coronary syndrome, EF – ejection fraction, HDL – high-density lipoprotein, LAD – left anterior descending, LDL – low-density lipoprotein, MI – myocardial infarction, OR – odds ratio, PLR – platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, RDW – reticulocyte distribution width, STEMI – ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

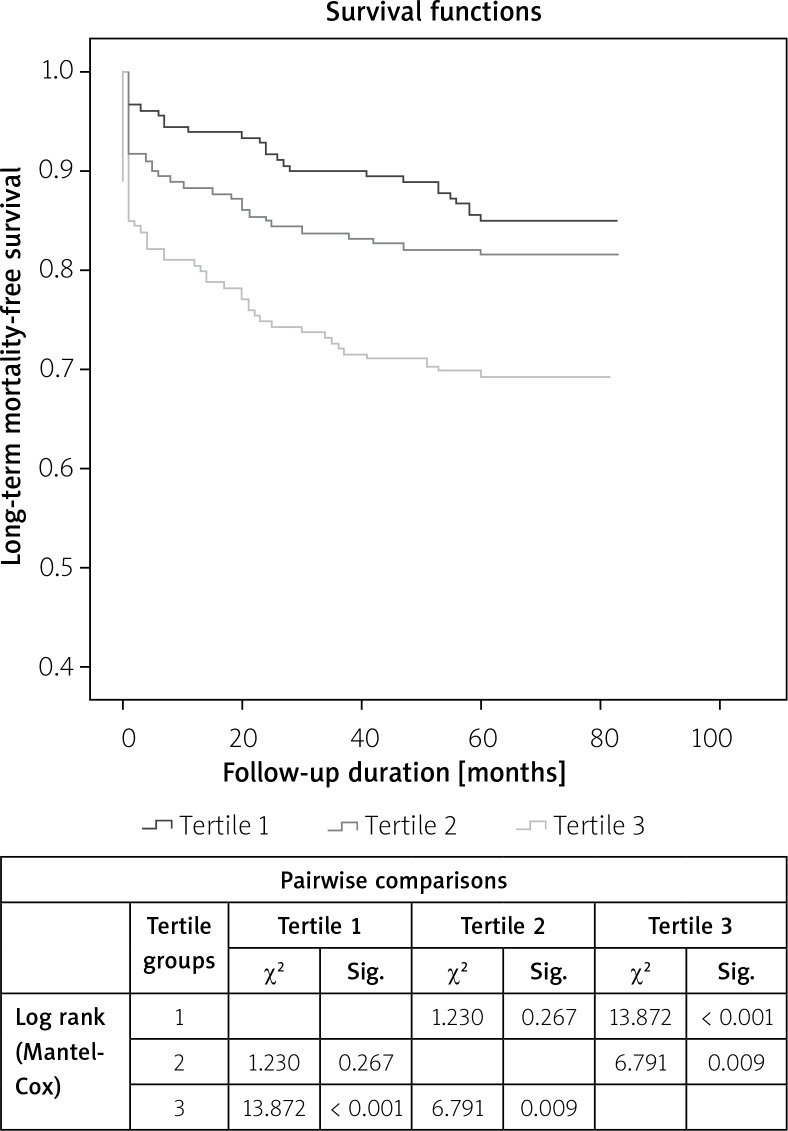

Kaplan-Meier analysis according to the long-term mortality-free survival revealed the higher occurrence of mortality in the third PLR tertile group compared to the first (p < 0.001) and second tertiles (p = 0.009; Figure 2). In addition, in the Spearman correlation analysis, we found a statistically significant positive correlation between C-reactive protein (CRP) and PLR (r = 0.198, p = 0.018).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis according to long-term mortality-free survival of PLR tertile groups

Discussion

In this study, we focused primarily on the assessment of the relation between admission PLR and long-term mortality in patients with ACS. We demonstrated that higher PLR is a significant independent predictor of long-term mortality in patients with ACS. Patients with high PLR had more severe cardiovascular risk factors but Cox regression analysis showed the independent association of PLR with long-term mortality.

Acute coronary syndrome is characterized by thrombus formation beside ruptured vulnerable plaque causing vessel occlusion [16]. Therefore, risk stratification is a major issue to manage ACS. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) score is one of the most important scores used in predicting early in-hospital and 6-month mortality in patients with ACS. However, calculating this score is time consuming [17].

Inflammation plays an important role in the progression and instability of plaque. Some inflammatory biomarkers, such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, have been described as independent predictors of poor outcomes in ACS patients [18, 19]. In recent years, PLR, derived from platelet and lymphocyte counts and indicated as a useful indicator of systemic inflammatory response, was firstly used as a prognostic marker of some oncological diseases [20–22]. Then, this marker was shown to be associated with inflammation in cardiovascular diseases [11–15]. In addition, PLR has been reported to correlate with other inflammatory markers such as CRP and fibrinogen, which have proven to be predictive and prognostic in cardiovascular disease [23].

Although the exact underlying mechanism of adverse outcomes in patients with elevated PLR levels in patients with ACS cannot be clearly elucidated, PLR has been shown to be associated with increased inflammatory activity and severe pro-thrombotic status. The cause of this severe pro-thrombotic condition is megakaryocytic proliferation and relative thrombocytosis [24, 25]. A high platelet count is indicative of both an outcome and an inflammatory response. Some inflammatory mediators have been reported to increase platelet production by stimulating megakaryocytes and accelerating proliferation [26]. Also, platelets release thromboxane and some mediators, causing increased inflammation and sensitization of the atherosclerotic plaque, leading to plaque rupture [27, 28]. In addition, high platelet counts may lead to worse outcomes by contributing to the progression of arterial thrombus during thrombosis [29].

On the other hand, lymphocytes, which are an important part of chronic inflammation in the atherosclerotic process and have a high number in the ischemic and reperfused myocardium during ACS, increase plaque stability in coronary artery disease patients [30]. Cortisol is released in response to physiological stress during myocardial ischemia/infarction. Cortisol elevation causes lymphopenia [31]. Therefore, lower lymphocyte levels are associated with more negative outcomes in ACS patients. On the other hand, a high lymphocyte count may be an indicator of a more appropriate immune response that leads to better outcomes in patients with unstable angina [32].

When all these effects are evaluated together, both thrombocytosis and lymphocytopenia reflect systemic inflammation. Therefore, PLR, which is a combination of two hematological parameters, may be more useful than either platelet or lymphocyte count alone in predicting the prognosis of ACS.

Previous studies have demonstrated the prognostic significance of PLR in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Azab et al. reported that PLR is a prognostic indicator of long-term mortality in the NSTEMI population [11]. Temiz et al. demonstrated that PLR was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients with STEMI [33]. Uğur et al. observed a relationship between high PLR level in STEMI and short-term clinical outcomes (up to 6 months) [34]. Ozcan Cetin et al. reported a significant association between high levels of PLR and both in-hospital and long-term cardiovascular poor outcomes in patients with STEMI [35]. Akkaya et al. found that high PLR levels were associated with in-hospital and short-term all-cause death in patients with STEMI after PCI [36]. In this study, we demonstrated that a high PLR level, which we have previously shown to be associated with in-hospital mortality, is also an independent predictor of long-term (60-month) mortality.

In all these studies, including our study, high PLR levels were associated with short- and long-term mortality. Therefore, this parameter may be a useful indicator for identifying patients at high risk for adverse events. Aggressive treatment, more frequent visits and closer follow-up may be required to reduce the mortality of these high-risk patients. In this context, PLR can contribute to traditional parameters used in existing risk scoring systems to estimate the in-hospital and long-term mortality risk of patients presenting with ACS.

Our study was a single-center study. We started patient inclusion in the study in 2012 and treatments were managed in line with the current guidelines at that time. Afterwards, although there was no major change in treatment management in the relevant guidelines, this situation should be taken into consideration. We did not evaluate inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 and thromboxane A2, and we also did not analyze the correlation of these parameters with PLR. The data of medical treatments given to all patients and the rate of compliance of patients with the treatments were not fully available. This is one of the limitations of our study. In addition, the use of a single blood sample during patient admission may not predict the persistence of PLR over time.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that high PLR level is an independent predictor of long-term poor prognosis in ACS patients. PLR, which is an easily calculated and universally available marker, can be included in clinical practice in risk classification of patients presenting with ACS. Further large-scale, multicenter studies are needed to evaluate the relationship between PLR and poor outcomes in patients with ACS.

Conflict of interst

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation. 2015;132:1667–78. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.008720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics-2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:948–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P, Rayner M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: epidemiological update. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2950–9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, et al. American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes: A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2114–30. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falk E, Nakano M, Bentzon JF, et al. Update on acute coronary syndromes: the pathologists’ view. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:719–28. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croce K, Libby P. Intertwining of thrombosis and inflammation in atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:55–61. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200701000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ommen SR, Gibbons RJ, Hodge DO, Thomson SP. Usefulness of the lymphocyte concentration as a prognostic marker in coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:812–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zouridakis EG, Garcia-Moll X, Kaski JC. Usefulness of the blood lymphocyte count in predicting recurrent instability and death in patients with unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:449–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00963-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azab B, Shah N, Akerman M, McGinn JT., Jr Value of platelet/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of all-cause mortality after non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012;34:326–34. doi: 10.1007/s11239-012-0718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oylumlu M, Yıldız A, Oylumlu M, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio is a predictor of in-hospital mortality patients with acute coronary syndrome. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:277–83. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kundi H, Gök M, Çetin M, et al. Relationship between platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and the presence and severity of coronary artery ectasia. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16:857–62. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2015.6639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oylumlu M, Doğan A, Oylumlu M, et al. Relationship between platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and coronary slow flow. Anatol J Cardiol. 2015;15:391–5. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yüksel M, Yıldız A, Oylumlu M, et al. The association between platelet/lymphocyte ratio and coronary artery disease severity. Anatol J Cardiol (ISI) 2015;15:640–7. doi: 10.5152/akd.2014.5565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–60. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang EW, Wong CK, Herbison P. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) hospital discharge risk score accurately predicts long-term mortality post-acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2007;153:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biasucci LM, Liuzzo G, Grillo RL, et al. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein at discharge in patients with unstable angina predict recurrent instability. Circulation. 1999;99:855–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartman J, Frishman WH. Inflammation and atherosclerosis: a review of the role of interleukin-6 in the development of atherosclerosis and the potential for targeted drug therapy. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22:147–51. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proctor MJ, Morrison DS, Talwar D, et al. A comparison of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with cancer. A Glasgow Inflammation Outcome Study. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RA, Bosonnet L, Raraty M, et al. Preoperative platelet-lymphocyte ratio is an independent significant prognostic marker in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2009;197:466–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith RA, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, et al. Prognosis of resected ampullary adenocarcinoma by preoperative serum CA19-9 levels and platelet-lymphocyte ratio. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1422–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0554-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gary T, Pichler M, Belaj K, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio: a novel marker for critical limb ischemia in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez-Porras JR, Martin-Herrero F, Gonzalez-Lopez TJ, et al. The role of immature platelet fraction in acute coronary syndrome. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:247–9. doi: 10.1160/TH09-02-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuentes QE, Fuentes QF, Andrés V, et al. Role of platelets as mediators that link inflammation and thrombosis in atherosclerosis. Platelets. 2013;24:255–62. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.690113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burstein SA, Mei RL, Henthorn J, et al. Leukemia inhibitory factor and interleukin-11 promote maturation of murine and human megakaryocytes in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1992;153:305–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041530210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Investig. 2005;115:3378–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI27196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindemann S, Kramer B, Seizer P, Gawaz M. Platelets, inflammation and atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(Suppl 1):203–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Srikanth S, Ambrose JA. Pathophysiology of coronary thrombus formation and adverse consequences of thrombus during PCI. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012;8:168–76. doi: 10.2174/157340312803217247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bian C, Wu Y, Shi Y, et al. Predictive value of the relative lymphocyte count in coronary heart disease. Heart Vessels. 2010;25:469–73. doi: 10.1007/s00380-010-0010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomson SP, McMahon LJ, Nugent CA. Endogenous cortisol: a regulator of the number of lymphocytes in peripheral blood. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1980;17:506–14. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(80)90146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caligiuri G, Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Maseri A. Immune system activation follows inflammation in unstable angina: pathogenetic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1295–304. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Temiz A, Gazi E, Güngör Ö, et al. Platelet/lymphocyte ratio and risk of in-hospital mortality in patients with ST-elevated myocardial infarction. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:660–5. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ugur M, Gul M, Bozbay M, et al. The relationship between platelet to lymphocyte ratio and the clinical outcomes in ST elevation myocardial infarction underwent primary coronary intervention. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2014;25:806–11. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ozcan Cetin EH, Cetin MS, Aras D, et al. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker of in-hospital and long-term major adverse cardiovascular events in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Angiology. 2016;67:336–45. doi: 10.1177/0003319715591751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akkaya E, Gul M, Ugur M. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio: a simple and valuable prognostic marker for acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:597–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.08.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]