Abstract

The health insurance Marketplaces established by the Affordable Care Act include features designed to simplify the process of choosing a health plan in the individual, or nongroup, insurance market. While most individual health insurance enrollees purchase plans through the federal and state-based Marketplaces, millions also purchase plans directly from an insurance carrier (off Marketplace). This study was a descriptive comparison of the decision-making processes and shopping experiences of consumers in two states who purchased a health insurance plan from the same large insurer in 2017, either through the federal Marketplace or off Marketplace. In a survey, those who selected plans on Marketplace reported less difficulty finding the best or most affordable plan than did those enrolling off Marketplace. Respondents in families with chronic health conditions who enrolled on Marketplace reported better overall experiences than those who enrolled off Marketplace. Respondents with low health insurance literacy reported poor experiences in enrolling either on or off Marketplace. Access to consumer assistance in the individual health insurance market should target off-Marketplace populations as well as all populations with low health insurance literacy.

Consumers who shop for health insurance in the individual, or nongroup, market face a complex decision with potentially large financial and health ramifications.1 Shoppers looking to minimize their financial exposure must predict their expected health care use and costs for a variety of scenarios across large numbers of plans with varying cost-sharing arrangements and provider networks. Some groups of people face circumstances that make this decision more challenging. For example, many shoppers have low health insurance literacy and lack the numeracy or understanding of insurance terms and functions necessary to calculate and weigh personal costs associated with plan options.2,3 Plan choice may also be difficult for those whose families have chronic health conditions: They must compare plans along multiple dimensions to determine overall affordability and access to providers, services, and prescriptions. Challenges with health plan choice can leave an enrollee at risk for unnecessarily high out-of-pocket spending4,5 or delayed care.6,7

In addition to the goal of expanding and improving health insurance coverage options for those without access to employer or public coverage, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) federal and state-based health insurance Marketplaces sought to improve the process of plan selection in the individual insurance market.8 (In this study, we focused on the federal Marketplaces, which are used in the majority of US states.) The federal Marketplaces use a web-based platform (HealthCare.gov) that supports plan selection from the shopping process through enrollment.9 Consumers can compare qualified health plans from different health insurance carriers in a structured environment that sorts plans by actuarial value using metal tiers (such as gold, silver, and bronze) and displays premium, deductible, and other cost-sharing information. Shoppers also have access to decision support tools—including a calculator that predicts yearly costs for each plan based on medical usage and a tool to show whether specific providers are included in plan networks. Consumers can also obtain personalized assistance from customer service representatives or certified enrollment specialists known as navigators.

Since the implementation of the Marketplaces in 2014, 10–12 million people have enrolled in Marketplace plans annually,10 and large majorities have reported satisfaction with their coverage, choice of providers, and plans overall.11,12 However, only 50 percent of enrollees nationally found it easy to find the right coverage, and only 41 percent believed it was easy to find an affordable plan.13 Consumers with shopping challenges are more likely than those without such challenges to have negative experiences in their plans.14

Consumers seeking a health plan in the individual insurance market can also purchase one outside of the Marketplace (off Marketplace), and 3.6 million enrollees (approximately a quarter of the total enrollees in ACA-compliant individual plans) are estimated to have done so in 2017.15 Most health plans offered on Marketplace can also be obtained off Marketplace by purchasing directly from the insurance carrier or through a broker. Off-Marketplace consumers may also have additional plan options not available on the Marketplace. However, federal premium and cost-sharing subsidies are not available to those enrolled in off-Marketplace plans. The experiences of off-Marketplace enrollees and how they compare to those who enrolled through the Marketplaces are unclear. As policy makers grapple with decisions about the health insurance Marketplaces and the individual market in general, understanding differences in public experiences on and off the Marketplace can help inform approaches to future reform.

To assess consumer experience, we surveyed enrollees in individual market plans offered by the same large insurance carrier both on and off the federal Marketplace in two states. This study offers an advantage over other survey studies by using administrative data to accurately identify the coverage source (on versus off Marketplace) and plan benefits of surveyed enrollees. We also evaluated the processes and experiences of two subgroups thought to be at risk for greater challenges in comparing and choosing coverage: people with low health insurance literacy and families with chronic conditions (at-risk groups).

Study Data And Methods

Data And Study Population

We mailed surveys to enrollees ages 18–63 in Harvard Pilgrim Health Care (HPHC), a large nonprofit health insurance carrier, in 2017. Surveys were mailed to a sample of enrollees who had newly enrolled or reenrolled in an individual market health plan either on or off Marketplace in New Hampshire or Maine following the 2017 open enrollment period. HPHC represented a quarter of the enrollees in ACA-compliant plans in the individual markets of these states overall and held a similar share of enrollment on and off Marketplace (see online appendix section 6 for details).16 HPHC offered only health maintenance organization plans, which were also offered by the other major carriers in both states on and off Marketplace. The set of available HPHC plans were similar on and off Marketplace: Only two plans that covered 2 percent of HPHC individual market enrollees were available exclusively off Marketplace.

We selected a random sample of 4,506 enrollees (22 percent of all individual market enrollees in HPHC) stratified by state and enrollment source (on or off Marketplace). The sample included people who had individual coverage and those with family (dependent) coverage. We refer to these insurance units hereafter as families, including families of one. The overall survey response rate was 32 percent, yielding 1,433 respondents (for the numbers of respondents within strata, see appendix exhibit A3).16 Survey questions were tested and revised using cognitive interviews with HPHC individual market members, and the survey was fielded in the period March–May 2017. All respondents received a $20 incentive.

Respondents answered survey questions on behalf of themselves and any family members sharing their plan. Survey questions focused on plan characteristics considered, information used, assistance received, and experiences in choosing their health plan for 2017 (see the appendix for a copy of the survey instrument).16 To measure shopping experiences, subjects were asked for their overall rating of the experience trying to get health insurance on a five-point scale, the amount of time spent comparing and choosing their plan, and the difficulty of finding the most affordable plan and the difficulty of finding the best plan for them on a four-point scale. For analysis, these variables were dichotomized according subjective groupings of positive and negative responses. Having difficulty finding the most affordable plan and finding the best plan were highly correlated, so we combined them into a single binary measure of reporting “very difficult” or “somewhat difficult” for either question. We used enrollment records to link survey responses to the respondent’s demographic information (including age, sex, and whether there were children younger than eighteen enrolled in their plan), whether they had reenrolled in the same plan they had in 2016 or switched plans (switching within HPHC or joining HPHC in 2017), and plan attributes. Additional demographic characteristics collected via the survey included education level, race/ethnicity, self-rated health status of the least healthy family member, and household income. We used self-reported household income and number of family members living in the household to approximate family income as a percentage of the federal poverty level in 2017.

Respondents were asked if they or any family members in their plan had a chronic health condition (defined in the survey as a health condition that has lasted or is expected to last a year or longer, may limit what one can do, and may require ongoing care—conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, and asthma). If a respondent selected “yes,” we classified the respondent as from a “family with chronic conditions.” We determined health insurance literacy using a thirteen-item measure that gauges the respondent’s confidence in understanding insurance terms and performing certain activities.17 We sorted respondents into tertiles of health insurance literacy according to overall level of confidence across all measures (see section 1 of the appendix for further details on the measurement of health insurance literacy).16

Analysis

We reported unadjusted descriptive statistics for all respondents and each at-risk subgroup, and we used chi-square tests of equivalence and t-tests to test for differences between each subgroup.

We estimated separate multivariable logistic regression models to analyze the association between shopping experiences (plan characteristics considered, sources of information used, assistance received, and perceptions of plan choice experiences) and whether the respondent enrolled in a health plan on or off Marketplace (our main model). Independent variables included age, sex, education, income, race, family composition and employment, state, number of family members in the plan, and prior insurance type. We also tested whether Marketplace participation was associated with different shopping experiences among the two at-risk groups by estimating our main model with an interaction term for enrolling through the Marketplace and being in each at-risk population. To investigate experiences in the absence of financial assistance, we ran our analyses restricted to populations likely to be ineligible by income for subsidies (respondents with incomes of more than 400 percent of poverty). To evaluate the role of using a broker on experiences, we separately ran models that controlled for broker use. Results are reported as predicted probabilities from these models, standardized to the population from which the study sample was drawn; model results are presented in section 5 of the appendix.16 We implemented multiple imputation to estimate all missing responses. Missing data were less than 5 percent for all covariates except household income, where they were 8 percent. All unadjusted and adjusted analyses were weighted using inverse probability weights to account for sampling design and subject-level nonresponse. (See sections 2a and 2b of the appendix for more detailed descriptions of our multiple imputation and weighting methods.)16

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, survey respondents came from a single insurance carrier in one region of the country, which limited generalizability. Nevertheless, New Hampshire and Maine use the federal Marketplace, which is used in the majority of US states—thus broadening the scope of where these findings will be relevant.

Second, respondents selected whether to enroll in a health plan on versus off Marketplace, and differences in available plans or other unmeasured individual or carrier attributes could be associated both with choice of Marketplace and with shopping experiences. (For example, more plans were available off Marketplace than on Marketplace in both states during the study period. However, the dominant carriers in these states offered plans both on and off Marketplace, and most of the off-Marketplace plans were similar to those on Marketplace, given the requirements for ACA-compliant plans.) This selection issue constrained our ability to make causal inferences. Therefore, comparisons between experiences on versus off Marketplace should be considered observed associations rather than causal relationships.

Third, some respondents may have considered plans using both on and off Marketplace channels, which could cross-contaminate their experiential responses. To address this, we reran our analyses excluding sixty-nine off-Marketplace respondents who indicated that they had also looked at plans using Healthcare.gov, and our conclusions were unchanged (see section 4 of the appendix for these results).16

Fourth, health insurance literacy was self-reported and may not reflect true literacy. Additionally, respondents with limited English proficiency were likely underrepresented in our survey.

Fifth, our survey-based measure of self-reported income as a percentage of poverty may be imprecise, and some measurement error is likely. However, we tested our analyses by instead measuring income using the categories listed on the survey instead of derived poverty groupings, and the results did not differ meaningfully.

Finally, survey nonresponse was a limitation. However, our response rate is in line with rates achieved in similar work,18,19 and we were able to weight observations for nonresponse using administrative data.

Study Results

Our study population was predominantly white (exhibit 1). Sixty-nine percent had a household income at or below 400 percent of poverty, and the majority were either at an age approaching retirement (ages 56–63) or young (ages 35 or younger). Compared with respondents who purchased their plans off Marketplace, those who purchased on Marketplace were more likely to be younger and female and to have less education, lower health insurance literacy, and lower household incomes. They were less likely to be self-employed. The demographic differences between enrollees on and off Marketplace, apart from age, reflected differences that have been observed nationally.20

Exhibit 1:

Characteristics of survey respondents and the health plans they chose, by respondent Marketplace enrollment, chronic conditions, and health insurance literacy

| Marketplace enrollment | In family with chronic condition | Health insurance literacy tertile | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 1,433) | No (n = 646) | Yes (n = 787) | No (n = 956) | Yes (n = 460) | Top (n = 419) | Bottom (n = 483) | |

| Respondent characteristic | |||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Less than 36 | 28.7% | 20.0%*** | 30.8% | 34.2%*** | 17.0% | 20.8%*** | 34.0% |

| 36–45 | 15.9 | 14.9 | 16.1 | 15.1 | 18.0 | 17.5 | 19.8 |

| 46–55 | 21.8 | 25.2 | 21.0 | 21.6 | 21.6 | 20.1 | 20.6 |

| 56–63 | 33.6 | 40.0 | 32.1 | 29.1 | 43.4 | 41.6 | 25.6 |

| Male | 46.7 | 51.8* | 45.4 | 46.5 | 46.7 | 50 | 43.9 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 94.6 | 93.7 | 94.8 | 94.6 | 94.5 | 94.6 | 93.7 |

| College degree or more | 52.7 | 62.3*** | 50.3 | 54.5** | 47.7 | 54.3 | 51.6 |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 40.5 | 32.3*** | 42.5 | 42.8*** | 35.3 | 37.2 | 42.9 |

| Self-employed | 34.5 | 43.5 | 32.3 | 36.3 | 30.5 | 35.8 | 34.2 |

| Retired | 8.6 | 13.1 | 7.5 | 7.2 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 5.5 |

| Not working or other | 16.4 | 11.1 | 17.7 | 13.8 | 22.2 | 15.7 | 17.4 |

| Very or somewhat confident on all health insurance literacy questions | 22.8 | 28.4*** | 21.4 | 21.1*** | 26.5 | 63.6*** | 0.0 |

| Household income (% of FPL) | |||||||

| Less than 101 | 11.3 | 1.8*** | 13.5 | 10.2 | 13.6 | 8.7** | 12.2 |

| 101–250 | 36.5 | 7.1 | 43.4 | 37.6 | 34.4 | 34.8 | 41.9 |

| 251–300 | 10.1 | 6.9 | 10.9 | 10.7 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 11.1 |

| 301–400 | 11.4 | 15.0 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 10.2 |

| More than 400 | 30.7 | 69.1 | 21.7 | 30.0 | 31.7 | 36.6 | 24.6 |

| Mean number of family members in the plan | 1.6 | 1.9*** | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| Family member has a chronic condition | 31.9 | 30.4 | 32.3 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 38.9*** | 27.4 |

| Family member in fair or poor health | 10.6 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 5.2*** | 22.5 | 10.9** | 13.9 |

| Plan characteristic | |||||||

| On Marketplace | 80.4 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 80 | 81.4 | 74.5*** | 84.8 |

| New in 2017 | 54.4 | 47.4*** | 56 | 57.4*** | 47.8 | 55.7 | 54.1 |

| Metal tier | |||||||

| Bronze | 43.0 | 52.7*** | 40.6 | 47.2*** | 34.1 | 42.7 | 44.4 |

| Silver | 50.8 | 32.4 | 55.3 | 48.7 | 55.3 | 49.5 | 50.6 |

| Gold | 6.2 | 14.8 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 10.6 | 7.8 | 5.0 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a survey of enrollees in individual market health insurance plans offered by Harvard Pilgrim Health Care in New Hampshire and Maine in 2017. NOTES Unadjusted analyses were weighted using inverse probability weights to account for sampling design and subject-level nonresponse. Sample sizes were unweighted, and all other estimates were weighted. <<Missing responses in this table were not imputed, therefore the number of respondents may not always equal the total of 1433.>> Groupwise tests of equivalence were performed using chi-square and t tests that compared on and off Marketplace, with and without chronic condition, and low and high health insurance literacy. An expanded version of this table can be found in section 3a of the appendix (see note 16 in text). FPL is federal poverty level.

<<**p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01>>

Respondents in families with chronic conditions were older, had less education and higher health insurance literacy, and were more likely to choose gold health plans (and less likely to choose bronze plans), compared to those not in such families. Respondents in the bottom tertile of health insurance literacy were more likely to be younger and have lower incomes, compared to those in the top tertile. Health insurance literacy was unassociated with having a college degree or more education.

Many of the considered characteristics of plans and much of the information used in choosing plans were similar for respondents on and off Marketplace, but important differences were found among at-risk subgroups. Respondents from families with chronic conditions were overall less likely to say that the premium was their most important consideration and considered a wider variety of plan characteristics (including if a plan’s network included specific providers, the plan’s copayment amounts, and whether specific medications would be covered), compared to respondents in families without chronic conditions (exhibit 2). Respondents in families with chronic conditions were also more likely to use a provider finder and a prescription drug finder decision support tool. Respondents with low health insurance literacy were less likely than those with high health insurance literacy to use decision support tools.

Exhibit 2:

Plan characteristics considered and information used by health insurance plan enrollees in decision making, by Marketplace enrollment, chronic conditions, and health insurance literacy

| Marketplace enrollment | In family with chronic condition | Health insurance literacy tertile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | Top | Bottom | |

| Considered when choosing plana | ||||||

| Premium | 91% | 89% | 91% | 88% | 89% | 90% |

| Deductible | 74 | 75 | 73 | 77 | 78** | 70 |

| Copayments | 58 | 58 | 56** | 63 | 58 | 54 |

| Overall affordability | 73 | 78 | 75 | 77 | 78 | 75 |

| Coverage of specific doctor or hospital | 59 | 60 | 56*** | 67 | 63 | 59 |

| Number of doctors and hospitals in network | 29*** | 18 | 22 | 24 | 26 | 22 |

| Coverage of specific medications | 22 | 24 | 17*** | 36 | 23 | 22 |

| Plan quality ratings | 11 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 10 |

| Out-of-pocket spending maximum | 54 | 50 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 47 |

| Plan reputation | 21 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 21 | 17 |

| Prior experience with the plan or carrier | 27 | 22 | 22** | 29 | 27 | 23 |

| Recommendations from friends or family | 8 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 9 |

| Only considered plans that included a specific doctor or hospital | 54 | 54 | 49*** | 63 | 55 | 52 |

| Premium was most important consideration | 43 | 38 | 44*** | 33 | 38 | 43 |

| When choosing plan, used information from:a | ||||||

| Estimate of total yearly costs | 46 | 41 | 43 | 44 | 48** | 39 |

| Provider finder | 45 | 44 | 42** | 49 | 48 | 40 |

| Network size | 18** | 11 | 15 | 13 | 15 | 15 |

| Prescription drug finder | 17 | 18 | 13*** | 28 | 19 | 15 |

| Plan quality ratings | 12 | 9 | 11 | 9 | 14 | 9 |

| None of the above | 30 | 32 | 32 | 29 | 27** | 35 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a survey of enrollees in individual market health insurance plans offered by Harvard Pilgrim Health Care in New Hampshire and Maine in 2017. NOTES The percentages reflect model-adjusted predicted probabilities when sociodemographic and other population characteristics were controlled for (including Marketplace enrollment, chronic condition, and health insurance literacy), weighted using inverse probability weights to account for sampling design and subject-level nonresponse.

Respondents were asked to select all responses that applied. Significance was <<determined by a Wald test.>>

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

A lower proportion of Marketplace respondents received assistance when making their decision about which plan to choose, compared to those who enrolled off Marketplace (44 percent versus 61 percent) (exhibit 3). Accordingly, Marketplace respondents were also more likely to say that they wished they had had help (19 percent versus 9 percent). Brokers represented the most common source of help both on and off Marketplace, followed by family or friends, but off-Marketplace respondents were almost twice as likely to have received assistance from brokers than on-Marketplace respondents (40 percent versus 23 percent). Only 5 percent of on-Marketplace respondents received help from customer service representatives or navigators.

Exhibit 3:

Help with choice of a health plan received by health insurance plan enrollees, by Marketplace enrollment, chronic conditions, and health insurance literacy

| Marketplace enrollment | In family with chronic condition | Health insurance literacy tertile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | Top | Bottom | |

| Had help making decision | 61%*** | 44% | 52% | 50% | 49% | 55% |

| Helped by:a | ||||||

| Broker | 40*** | 23 | 32 | 29 | 31 | 35 |

| Family or friends | 18 | 16 | 16 | 18 | 13 | 17 |

| HealthCare.gov customer service representative | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Navigator | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Someone at doctor’s office or hospital | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0*** | 2 |

| Someone from the insurance company | 8*** | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Had no help | 39*** | 56 | 48 | 50 | 51 | 45 |

| Wished had had help | ||||||

| Yes | 9*** | 19 | 14 | 16 | 6*** | 23 |

| No | 29** | 36 | 33 | 33 | 45*** | 21 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from a survey of enrollees in individual market health insurance plans offered by Harvard Pilgrim Health Care in New Hampshire and Maine in 2017. NOTES The percentages reflect model-adjusted predicted probabilities as explained in the notes to exhibit 2. Respondents were asked if they had help making their health plan decision and the sources of that help. Those who said that they did not receive help were asked if they wished they had had help. Percentages within a column indicate the proportion of total respondents within that column who gave the corresponding response.

Respondents were asked to select all responses that applied. Significance was <<determined by a Wald test.>>

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

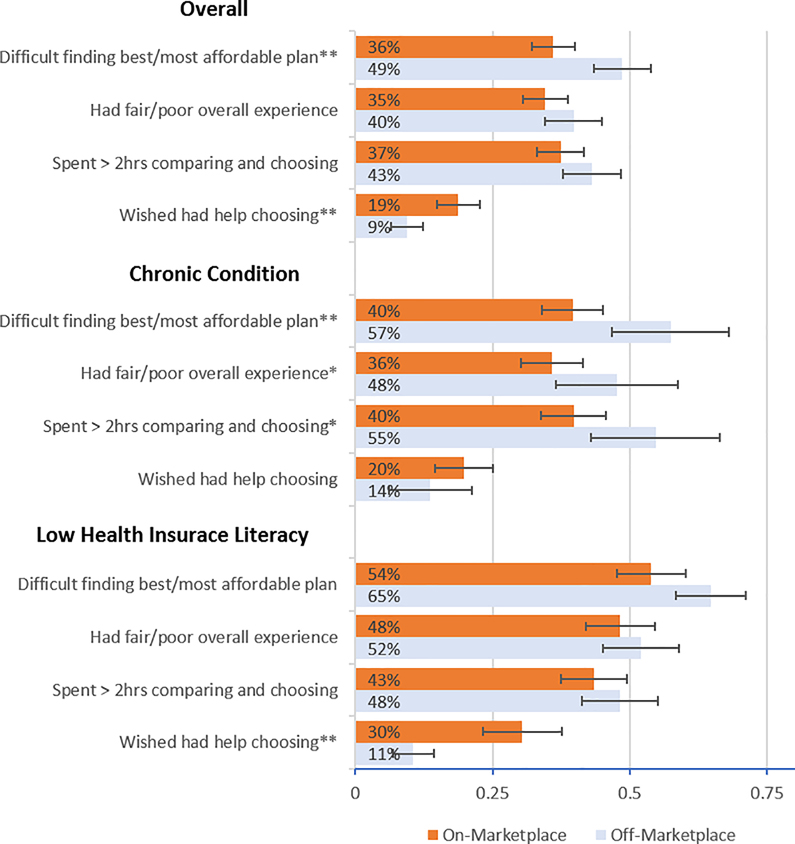

Respondents in families with chronic conditions and those with low health insurance literacy were equally likely to receive help and received similar types of help as those without chronic conditions and those with high health insurance literacy, respectively. However, respondents with low health insurance literacy were more likely to say that they wished they had had help, compared to those with high health insurance literacy (23 percent versus 6 percent) (exhibit 3). This unmet need was more pronounced on Marketplace, where more people with low health insurance literacy wished they had had help, compared to their off-Marketplace peers (30 percent versus 11 percent) (exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4.

Percentages of respondents reporting types of experiences in choosing a health plan on and off the Marketplace in 2017, overall and by at-risk group

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from their survey of enrollees in individual market health insurance plans offered by Harvard Pilgrim Health Care in New Hampshire and Maine in 2017. NOTES The percentages reflect model-adjusted predicted probabilities when sociodemographic and other population characteristics were controlled for, weighted using inverse probability weights to account for sampling design and subject-level nonresponse. Section 5 of the appendix includes regression tables (see note 16 in text). Comparisons of enrollees in families with chronic conditions (“Chronic condition”) and with low health insurance literacy in on- versus off-Marketplace plans were calculated from a model that interacted chronic condition with Marketplace participation and one that interacted health insurance literacy with Marketplace participation, respectively. Significance was determined by a Wald test. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. **p < 0.05 ***p < 0.01

Respondents who enrolled through the Marketplace were less likely to have had difficulty finding the best or most affordable plan than those who enrolled off Marketplace (36 percent versus 49 percent) (exhibit 4). Compared to respondents who did not use a broker, those who did reported lower rates of fair or poor experience (29 percent versus 40 percent; p <0.01) and spending more than two hours choosing (32 percent versus 44 percent; p <0.01), though controlling for use of brokers did not materially change our findings on differences in experiences on versus off Marketplace (appendix section 3c, exhibit A5)16

At-risk groups were significantly more likely to report negative experiences shopping than their less vulnerable counterparts: Those in families with chronic conditions had significantly greater odds of having difficulty finding the best or most affordable plan, and those with low health insurance literacy had significantly greater odds of all three negative shopping experiences (appendix section 5, exhibits A7–A9).16 Among respondents in families with chronic conditions, compared to enrolling off Marketplace, doing so on Marketplace was associated with less difficulty choosing the best or most affordable plan (40 percent versus 57 percent), spending more than two hours choosing (40 percent versus 55 percent), and having a fair or poor experience (36 percent versus 48 percent) (exhibit 4). However, respondents with low health insurance literacy did not have significantly different experiences enrolling on versus off Marketplace, with high proportions in both cases reporting difficulty choosing (54 percent versus 65 percent), fair or poor experiences (48 percent versus 52 percent), and spending more than two hours selecting a plan (43 percent versus 48). Results regarding shopping experiences were similar in sensitivity analyses that excluded respondents with incomes eligible to receive financial assistance (at or below 400 percent of poverty) (appendix section 3b).16

Discussion

Before the ACA, the small proportion of Americans with individual market insurance coverage was declining,21 and perceived information search costs and affordability were believed to be among the primary barriers to participation.22 Participation in the individual market roughly doubled following implementation of the ACA’s Marketplaces and subsidies, provisions to stabilize the individual market, the individual mandate, and outreach efforts starting in 2014.20,23

Four years into the operation of the ACA Marketplaces, this study found worse reported experiences among off-Marketplace enrollees than among on-Marketplace enrollees, who expressed less difficulty finding the best or most affordable option despite receiving less in-person assistance than off-Marketplace shoppers. Differences in the shopping contexts on and off Marketplace might explain these results. The standardized comparisons of plan coverage available through HealthCare.gov and online tools such as provider finders allow simultaneous comparison across plans and carriers that is not possible when purchasing directly from an insurance carrier and may be helping improve experiences. Off-Marketplace shoppers also had more plan choices (we estimated 35 percent more plan options in New Hampshire and 43 percent more in Maine), which could explain higher difficulty—although shoppers faced high numbers of choices on the Marketplace as well (about thirty-five plans in each state),24 and the extent to which off-Marketplace enrollees were exposed to all available options is unclear.

Particular subgroups of individual market enrollees (those in families with chronic conditions and those with low health insurance literacy) had higher rates of negative experiences when choosing a health plan compared to their healthy and more insurance-literate counterparts. Both chronic conditions and poor health insurance literacy are common among shoppers in the individual market,4,23,25 which places large numbers of enrollees at risk for poor experiences and negative downstream effects—including unmet health care need due to cost and negative health outcomes.2,9

However, for enrollees in families with chronic conditions, those who purchased a plan through the Marketplace were significantly less likely to report negative shopping experiences than those purchasing plans off Marketplace. Whether this difference in experience is due to Marketplace features (such as having more easily accessible information and comparison infrastructure to tackle the high-dimensionality choices they faced) is an important question for future research.

Enrollees with low health insurance literacy had challenges both on and off Marketplace in terms of finding the best and most affordable plan, satisfaction, and time spent choosing. Where they differed is that nearly one-third of them who enrolled on Marketplace reported wishing that they had had help choosing a plan, which was more than double the number for off-Marketplace enrollees. One possible explanation for this difference is that navigators helped only a small percentage of enrollees in our study and nationally,25 perhaps due to their focusing on roles other than assisting with plan choice.26 Our survey also revealed that brokers were a common source of assistance off Marketplace, but their on-Marketplace role was more limited. Alternatively, the information on health plans aggregated and presented on Marketplace may have been overwhelming for some populations.27 Regardless of the explanation, Marketplace assistance and outreach efforts are missing many people in a population that stands to gain the most from them. Better understanding of this result can inform policy maker investment in resources to assist with plan selection.

Policy Implications

The findings in this study suggest that there are features of the ACA Marketplaces that consumers are finding useful in comparing and selecting health plans. Cost estimators and provider finder decision support tools were used in particular by families with chronic conditions. In the current environment, the future of the ACA Marketplaces is increasingly uncertain due to ongoing budgetary and regulatory changes. These decision support tools may become increasingly important in the face of this added volatility and complexity.

Despite educational efforts that were made at the community and national levels to improve health insurance literacy among individual market enrollees,28 the high degree of negative experiences reported by enrollees in our study with low health insurance literacy signals that more could be done to educate shoppers, connect them with assistance, and provide a simplified shopping environment. Enrollees with low health insurance literacy had less use of decision support tools and a greater desire for help in our study, which suggests that Marketplace tools and support may need to be better targeted and more user-friendly. Other strategies might also be considered. Marketplaces and enrollment assisters are currently prevented from making plan recommendations due to concerns over inappropriate steering. With proper safeguards, allowing assisters to make recommendations based upon shopper preferences might help people with low health insurance literacy.29 Beyond offering assistance, limiting the number of plan offerings and standardizing plan benefits—as some active purchaser state-based Marketplaces have done—could reduce choice overload due to numerous nonstandardized plan choices and help consumers with low health insurance literacy.27,30,31

Finally, with the withdrawal of federal enrollment support and outreach, states may have to draw upon alternative resources if they want to continue and expand efforts to bolster participation in the individual insurance market.32 States where the off-Marketplace use of brokers is common might consider strategies to engage them to assist a wider range of consumers.

Conclusion

This descriptive study found that ACA Marketplace enrollees reported better shopping experiences than those enrolling off Marketplace in the individual insurance market in two states—particularly those in families with chronic conditions. However, a significant minority of enrollees overall and roughly half of enrollees with low health insurance literacy reported negative experiences both on and off Marketplace. Further reforms to simplify choices and expand the formats and outreach of decision support could address the diverse needs of people and families so as to continue to improve shopping experiences in the individual market.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Portions of this research were presented at AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Seattle, Washington, on June 25th, 2018. This project was supported by grant number R01HS024700 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Joachim Hero was supported by a Thomas O. Pyle Fellowship and a Robert H. Ebert Award from the Department of Population Medicine at the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. Alison Galbraith also receives grant support for other research projects from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. The authors thank Jessica Young, Lauren Cripps, and Wyatt Koma for thoughtful comments and assistance. They also thank Nancy Turnbull, Karen Quigley, Stephanie Richardson, Scott Bugbee, James Vancor, and Michael Singer.

Biography

Bios for 2018–05036_Hero

Bio 1: Joachim Olivier Hero (joachim_hero@harvardpilgrim.org) is a research fellow in health policy at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute <<and Harvard Medical School, in Boston>>.

Bio 2: Anna D. Sinaiko is an assistant professor of health economics and policy in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

Bio 3: Jon Kingsdale is an associate professor of the practice in the Department of Health Law, Policy, and Management, Boston University School of Public Health <<, in Boston, and an adjunct professor of the practice at Brown University, in Providence>>

Bio 4: Rachel S. Gruver is a doctoral student in epidemiology at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, in New York City.

Bio 5: Alison A. Galbraith is an associate professor of population medicine at Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute and Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

Notes

- 1.Cunningham PJ. The share of people with high medical costs increased prior to implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loewenstein G, Friedman JY, McGill B, Ahmand S, Linck S, Sinkula S, et al. Consumers’ misunderstanding of health insurance. J Health Econ. 2013;32(5):850–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long SK, Kenney GM, Zuckerman S, Goin DE, Wissoker D, Blavin F, et al. The Health Reform Monitoring Survey: addressing data gaps to provide timely insights into the Affordable Care Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(1):161–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhargava S, Loewenstein G. Choosing a health insurance plan: complexity and consequences. JAMA. 2015;314(23):2505–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhargava S, Loewenstein G, Sydnor J. Choose to lose: health plan choices from a menu with dominated option. Q J Econ. 2017;132(3):1319–72. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CA, Asch DA, Vinoya CM, Ford CA, Baker T, Town R, et al. The experience of young adults on HealthCare.gov: suggestions for improvement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(3):231–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morgan RO, Teal CR, Hasche JC, Petersen LA, Byrne MM, Paterniti DA, et al. Does poorer familiarity with Medicare translate into worse access to health care? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jost TS. Health insurance Exchanges and the Affordable Care Act: key policy issues [Internet]. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2010. July [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2010_jul_1426_jost_hlt_insurance_exchanges_aca.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingsdale J After the false start—what can we expect from the new health insurance Marketplaces? N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):393–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claxton G, Levitt L, Damico A, Rae M. Data note: how many people have nongroup health insurance? [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. January 3 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/how-many-people-have-nongroup-health-insurance/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins SR, Gunja M, Doty MM, Beutel S. Americans’ experiences with ACA Marketplace and Medicaid coverage: access to care and satisfaction [Internet]. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2016. May [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_issue_brief_2016_may_1879_collins_americans_experience_aca_marketplace_feb_april_2016_tb.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirzinger A, Hamel L, Muñana C, Brodie M. Kaiser Health Tracking Poll—March 2018: non-group enrollees [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. April 3 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-march-2018-non-group-enrollees/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunja MZ, Collins SR, Doty MM, Beutel S. Americans’ experiences with ACA Marketplace coverage: affordability and provider network satisfaction [Internet]. New York (NY): Commonwealth Fund; 2016. July 7 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/jul/americans-experiences-aca-marketplace-coverage-affordability-and [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sinaiko AD, Kingsdale J, Galbraith AA. Consumer health insurance shopping behavior and challenges: lessons from two state-based Marketplaces. Med Care Res Rev. 2017. July 1 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Semanskee A, Levitt L, Cox C. Data note: changes in enrollment in the individual health insurance market [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. July 31 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/data-note-changes-in-enrollment-in-the-individual-health-insurance-market/view/footnotes/ [Google Scholar]

- 16. To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 17.Holahan J, Long S. Health Reform Monitoring Survey, first quarter 2016 [Internet]. Ann Arbor (MI): Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; [distributor]; 2017. April 28 [cited 2019 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/HMCA/studies/36744/version/1 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fung V, Liang CY, Donelan K, Peitzman CG, Dow WH, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Nearly one-third of enrollees in California’s individual market missed opportunities to receive financial assistance. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long SK, Stockley K. Massachusetts health reform: employer coverage from employees’ perspective. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(6):w1079–87. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goddeeris JH, McMorrow S, Kenney GM. Off-Marketplace enrollment remains an important part of health insurance under the ACA. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1489–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen JW, Rhoades JA. Group and non-group private health insurance coverage, 1996 to 2007: estimate for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population under age 65 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. October [cited 2019 Jan 31]. (MEPS Statistical Brief No. 267). Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_files/publications/st267/stat267.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marquis MS, Buntin MB, Escarce JJ, Kapur K, Louis TA, Yegian JM. Consumer decision making in the individual health insurance market. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(3):w226–34. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.w226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karpman M, Long SK, Bart L. The Affordable Care Act’s Marketplaces expanded insurance coverage for adults with chronic health conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(4):600–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.HIX Compare. Individual market: current version: 2017. [Internet]. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; [updated 2018 Oct 1; cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available for download from: https://hixcompare.org/individual-markets.html [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamel L, Firth J, Levitt L, Claxton G, Brodie M. Survey of non-group health insurance enrollees, wave 3 [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. May 20 [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/survey-of-non-group-health-insurance-enrollees-wave-3/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollitz K, Tolbert J, Diaz M. Data note: changes in 2017 federal navigator funding [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2017. October 11 [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/data-note-changes-in-2017-federal-navigator-funding/ [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanius BE, Wood S, Hanoch Y, Rice T. Aging and choice: applications to Medicare Part D. Judgm Decis Mak. 2009;4(1):92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jahnke LR, Siddiqui NJ, Andrulis DP. Evolution of health insurance Marketplaces: experiences and progress in reaching and enrolling diverse populations [Internet]. Austin (TX): Texas Health Institute; 2015. July [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.texashealthinstitute.org/uploads/1/3/5/3/13535548/thi_marketplaces_&_diverse_populations_july_2015_-_full_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes AJ, Hanoch Y, Rice T. Can plan recommendations improve the coverage decisions of vulnerable populations in health insurance Marketplaces? PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Day R, Nadash P. New state insurance exchanges should follow the example of Massachusetts by simplifying choices among health plans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):982–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McWilliams JM, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG, Landon BE. Complex Medicare Advantage choices may overwhelm seniors—especially those with impaired decision making. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1786–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luthi S 39 navigators to receive grants to aid 2019 ACA enrollment. Modern Healthcare [serial on the Internet]. 2018. September 12 [cited 2019 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20180912/NEWS/180919960

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.