Abstract

Funeral services are known to serve multiple functions for bereaved persons. There is also a common, intuitively reasonable assumption of positive associations between engaging in funeral activities and adjustment to bereavement. We examined whether restricting ceremonial cremation arrangements to a minimum has a negative association with grief over time. Bereaved persons in the United Kingdom completed questionnaires 2 to 5 months postloss and again a year later (N = 233 with complete data; dropout = 11.4%). Neither type nor elaborateness of the cremation service, nor satisfaction with arrangements (typically high), emerged as significantly related to grief; no major subgroup differences (e.g., according to income level) were found. Results suggested that it does not matter to grief whether a more minimalistic or elaborate funeral ceremony was observed. We concluded that the funeral industry represented in this investigation is offering bereaved people the range of choices regarding cremation arrangements to meet their needs. Limits to generalizability are discussed.

Keywords: grief, bereavement, mourning, cremation, funeral

There are considerable differences among bereaved persons in intensities of grief and the course of their adjustment over time. Researchers have therefore prioritized the examination of the so-called risk factors, ones which are associated with the development of higher levels and/or longer duration of grief. A major aim of such studies has been to identify those most likely to experience trouble during their grieving, in order to focus on persons at high risk (e.g., of complications in their grief/grieving process), to work toward lowering their suffering, and to enhance the provision of help where needed. Many potential risk/protective factors have been examined, including intrapersonal ones (e.g., personal circumstances prior to the death; kinship to the deceased), situational ones relating to the death itself (e.g., expected versus unexpected), or interpersonal ones (e.g., availability of social and emotional support). Despite this broad coverage, and the fact that there is extensive literature on funeral practices, the role of funeral ceremonies does not feature prominently, if at all, as reflected in systematic risk factor reviews (e.g., Burke & Neimeyer, 2013; Kristensen et al., 2012; Lobb et al., 2010; Stroebe et al., 2006). Nevertheless, there is widespread belief that participating in body disposal-related ceremonies actually helps one’s grief (cf. Lensing, 2001; Mitima et al., 2019), from which it could be surmised that minimal or no observance of funeral rites would have a negative impact on adjustment to the loss of a loved one.

It is possible that circumstances may prevail to limit funeral participation, in which case, if benefits are indeed to be gained by taking part in such ceremonies, detrimental effects could ensue. There have been significant changes in services provided by the funeral industry to meet with contemporary societal norms and consumer needs, some of which minimalize the nature of ceremonial events surrounding body disposal. To take the case of the United Kingdom (where the empirical study reported later was conducted): developments in funeral practices have been particularly manifest here. Most notably for the current interest, there has been a growing percentage of cremations in the British Isles to approximately 78% in 2018 (The Cremation Society, 2019), and major changes have occurred in general in the provision of extended range of funeral options over recent years, partly—as a result of market and cultural transitions (a similar trend has been observed in the United States, cf. Beard and Burger 2020). These developments have been accompanied by an increase in the numbers of direct and unattended cremations (Royal London, 2016). The funeral industry has responded to consumer demand by offering more affordable/simplified solutions, with 5% of consumers choosing a direct cremation funeral and direct burials, despite these not being a mainstream offering. These data and the broadening of the range of cremation options suggest that there is demand for nontraditional affordable funerals (cf. Royal London, 2016). Concern has been expressed about the loss of benefit to the bereaved through such reductions in ceremonials surrounding burial or cremation (Birrell & Sutherland, 2016). It is thought that such options as direct cremation, with no attendance at the cremation and even perhaps without a memorial service, may indeed cost less—but actually come at a cost, diminishing opportunities for bereaved persons to take leave of the deceased in meaningful ways, ones that may serve to console and comfort family members and friends.

An underlying concern motivating our investigation was to examine whether contemporary changes in cremation practices which have been aimed in part to better-meet the needs of bereaved people could in fact have the paradoxical consequence of worsening the upset associated with bereavement. Empirical investigation can help clarify whether such concerns are justified. Therefore, the primary goal of the current project was to examine if funeral practices are a predictor of grief, by investigating connections between features of cremation and the experience of grief, specifically: Do the choices that bereaved persons make regarding their options for funeral arrangements relate to their course of grief and grieving?

Although the risk factor literature revealed little attention to the role of funerals, there is a burgeoning literature in the funeral domain which has provided relevant knowledge of use in designing our empirical study. We briefly review these sources next, covering background information on the range of body-disposal ceremonies; illustrating what is known in general about functions of funerals; and evaluating the extent to which empirical studies have provided scientific information on our research question. We make reference to studies of rituals too, since the topic of symbolic activities is clearly closely related to our research question, though it is not the focus of our own investigation.

Review of Scientific Studies of Funeral Practices and Grief

Information deriving from a systematic literature search is summarized next.1 As will become evident, the sources cover a wide range of studies and designs, qualitative and quantitative, large or small scale, descriptive or controlled, empirical research or more-theoretical, scholarly explorations.

First, there has been inventorization of the range of funeral practices (e.g., expansion of options). Dickinson (2012) reviewed the wide range of methods/memorializations and shifts to diverse contemporary trends and discussed the impact of change (e.g., cost-related ones). Walter et al. (2012) evaluated how the internet has changed the ways in which we die and mourn, considering how online practices may affect grief, thereby placing traditional practices in broader, contemporary perspective, including that of the social media (cf. Gibbs et al., 2015). Beard and Burger (2017) conducted a meta-analysis of U.S. studies inventorizing types of motives for changes in the industry: business-related versus consumer-related. While providing rich data for background understanding, the overview articles did not systematically review nor did the studies empirically examine the impact of body disposal ceremonies in direct association with adjustment to the loss of a close person.

Second, some studies have focused more specifically on issues surrounding funeral costs, difficulties, and—sometimes—adaptation. McManus and Schafer (2014) investigated the complex process underlying bereaved persons’ funeral expenditure, and its relationship with personal reactions (there was no quantification of specific psycho-social consequences). Kopp and Kemp (2007) examined the processes a consumer undertakes in making expensive decisions in stressful circumstances such as bereavement. Fan and Zick (2004) looked into the economic burden of funerals and burial expenses. Relatedly, Corden and Hirst (2013a, 2013b) have reported on the costs and burdens of bereavement in general and funerals in particular. Most recently, Lowe et al. (2019) focused on changing and improving memorial services for the bereaved. Taken together, these studies inform readers of the broad spectrum of types of arrangements and potential (financial) burden for bereaved people. They are valuable for the identification of funeral-related difficulties, especially economic ones, and helpful in the construction of our questionnaire.

Third, some researchers have explored the functions of funerals. For example, Lensing (2001) looked at the role of the funeral service in providing support for the bereaved and their grief, listing many ways that assistance was provided. There is an extensive literature on effects of rituals (to which we turn for relevant but not direct evidence—these studies are not of funeral arrangements per se). In an unusual experimental study, Norton and Gino (2014) explored the role of rituals in mitigating grief, demonstrating that they alleviated grief, through the mechanism of regaining feelings of control. Vale-Taylor (2009) examined reasons for performing rituals, including those beyond the funeral ceremony per se. This branch of the literature includes both historical and recent comparative accounts, including cultural differences in body disposition and memorialization (e.g., Hunter, 2007 comparing United States with Peruvian functions of rituals; for international comparison: Valentine & Woodthorpe, 2013). There have been a number of studies on the use of rituals in grief therapy (e.g., empty chair, writing letters, especially for unfinished business and ambivalent relationships; saying goodbye rituals; cf. Castle & Philips, 2003; Rando, 1985; Reeves, 2011; Sas & Coman, 2016) most of which have been descriptive. For example, Doka (2012) affirmed the value of funerals in general and of rituals in therapy, arguing the benefits of involvement in planning and of active participation. Such studies demonstrate many and varied functions of funerals and rituals and attest to beliefs by the bereaved themselves and health-care professionals as to their benefits. However, causal relationships have not been established. Studies evaluating their efficacy are missing. For example, although claims have been made about the therapeutic value of rituals, to the best of our knowledge, no randomized controlled trial investigation has been conducted. Many claims are based on descriptive accounts. These are intuitively plausible, but not yet, to our knowledge, tried and tested.

Fourth, coming closer to current interests, there have also been studies of satisfaction and preferences in association with death-related (specifically, body-disposal) ceremonies. Key questions addressed have been whether rituals are perceived to be helpful (if so, in what respects?) and whether the arrangements are found to be appropriate and appreciated. Some authors give subjective evaluations of perceived benefits or usefulness based on cross-sectional and/or qualitative information (e.g., Bolton & Camp, 1987, 1989; Castle & Phillips, 2003; Caswell, 2011; Servaty-Seib & Hayslip, 2003). For example, Servaty-Seib and Hayslip (2003) cross-sectionally examined the adjustment of adolescents and older persons following parental loss, finding that adolescents’ perceptions of the funeral reflected lower satisfaction and helpfulness, thereby addressing a question about subgroups: for whom do funerals help? (adolescents were less positive). O’Rourke et al. (2011) conducted a large empirical study which identified a number of predictors of satisfaction with funerals (e.g., religiosity). Of similar interest, Banyasz et al. (2017) looked into preferences for bereavement services, finding some differences in association with depression or complicated grief among the family members. In a small study, covering various durations of bereavement, Rugg and Jones (2019) examined what mattered to the bereaved regarding funerals. Although informative for both scientific and applied purposes, it must be noted that satisfaction with and/or preferences for funeral services/arrangements is a separate interest from establishing the relevance of cremation customs for adaptation in general and grief in particular: Establishing satisfaction with a service is not equivalent to assessment of its association with grief.

Finally, a few studies have directly addressed reactions to aspects of the funeral in relation to adaptation to the loss. Gamino et al. (2000) reported that those who found the funeral comforting and/or participated in planning showed less grief later on. There was indication that high scores on the measure of grief were associated with the occurrence of adverse funeral events (combined with not feeling comforted). Although this comes close to our research interest, the study had certain limitations. Importantly, it was conducted retrospectively, not prospectively, with assessment of the funeral taking place at the same—much later—time as the measure of grief intensity. Thus, it is likely that the negative perceptions about the funeral arrangements were colored by the high level of grief at the later time point when both of these were measured. Nevertheless, these authors drew attention to two potentially critical phenomena: They examined how funeral participation and the occurrence of adverse funeral events may be associated with grief adjustment and they pinpointed the possibility that if matters to do with the funeral go wrong, this may be associated with troubled grief. A longitudinal study conducted by Wijngaards-de Meij et al. (2008) examined the specific impact over time of circumstances surrounding death and burial. This investigation compared grief levels following cremation or burial. Similar levels of grief were found irrespective of the choice, as measured over time. In this study saying goodbye, presenting the body for viewing, was associated with lower levels of grief over time. One cannot conclude that saying goodbye reduces grief over time, but only that there is a significant relationship between these two variables.

The most recently published study revealed somewhat contrasting results to those mentioned earlier. Mitima-Verloop et al. (2019) examined the association between evaluations by bereaved people of the funeral (as well as their use of rituals), with their grief reactions. The investigation was longitudinal, and questionnaires were distributed at 6 months and 3 years postloss. Little impact of evaluations of the funeral (or rituals) with grief reactions was found: these body disposal-related customs were considered helpful, but there was no significant association with the bereaved participants’ grief reactions over the course of time. The authors pointed to the need for extended investigation. Of relevance here, dimensions of funerals were not examined in detail: Assessment was limited to four items covering general perceptions of the funeral ceremony (e.g., experiencing it as sad but positive, as important in processing the loss) and four items evaluating the funeral director (e.g., respectful, inspiring, decisive). Thus, our study has potential to build on this previous one.

In general, an extensive body of literature has accumulated on topics relating to the functions of funeral ceremonies (as well as those exploring purposes and practices of death rituals). Specifically for our interest, the literature search revealed studies of the variety and functions of funerals as well as studies indicating some benefits of specific rituals. However, few have actually addressed the question of a relationship between participating in funeral ceremonies with intensity and changes in levels of grief over time. In line with our conclusion, Mitima-Verloop et al. (2019) recently drew attention to the fact that very few empirical studies have examined the impact of performing rituals on recovery from the loss of a loved one, noting the paucity of studies examining whether a good farewell helps in coming to terms with the loss.

The Current Study

Our aim was to conduct a systematic, longitudinal, quantitative investigation of components of cremation services specifically (i.e., focusing on the arrangements which bereaved relatives choose to make) in relation to psychological adjustment (in terms of their levels of grief). We did so by examining bereaved persons’ decisions about constituent parts of the cremation which they had organized, and the relationships that these choices may or may not have on reactions to bereavement and the experience of grief and grieving over time.

The investigation was exploratory rather than hypothesis-testing in approach, since predictions could not firmly be made on the basis of earlier scientific studies. As indicated earlier, a couple of studies had shown that satisfaction with funerals, or specific features such as saying goodbye, was associated with lower levels of grief, but there was no research when we designed our study, which directly addressed the question of the impact of cremation arrangements on grief. Limited information from the more recent, well-designed Mitima-Verloop et al. (2019) study leads one—tentatively—not to expect close associations between cremation choices and grief reactions.

Methods

To achieve the goals outlined earlier, a questionnaire study was designed to examine features of cremation in relationship to grief over time, namely, at two time points, a year apart. Participants in the study, conducted in the United Kingdom, were selected on the basis of recency of bereavement and cremation, namely, 2 to 5 months prior to the start of the project. This study was part of a larger multiple method study into cremation and grief.

Procedure

In February 2018, a small (N = 12) feasibility study was conducted, which indicated a response rate around 50%—after a follow-up phone call to nonrespondents—and no major issues with regard to the length, wording, content, and character of the questionnaire and the procedure.

On the basis of that, a mailing was carried out by DignityUK, a national provider of funeral arrangements, to 1,942 potential respondents in April 2018, which included detailed information about the study, a request for participation, an informed consent form to be signed by the participant in case of participation, a questionnaire and a prestamped return envelope, addressed to the research team. In accordance with General Data Protection Regulations, the mailing consisted of a brief explanatory letter from DignityUK enclosing a sealed envelope which contained detailed information, the questionnaires to be returned to the University of Bath. This way names and contact information became available only for those who agreed to participate in the study. All potential participants were clients or contact persons for clients of DignityUK. A follow-up letter was issued to those who had not responded after 4 weeks.

A valid response rate of 13.5% for the first data collection point (T1) was achieved (N = 263). While we had anticipated a higher response rate on the basis of the feasibility study—although the follow-up phone call may have boosted the response rate there—given that the participants were relatively recently bereaved (2–5 months), this response rate probably had to be expected. Reasons for nonparticipation are unknown to the research team; further investigation by contacting nonparticipants to establish these would have been ethically unacceptable.

Questionnaires for the follow-up data collection point (T2) were sent out in April 2019, exactly a year after T1, between 14 and 17 months after the loss, to all persons who participated in T1. The attrition rate turned out to be exceptionally low, with 247 participants having returned the filled out second questionnaire. Three were removed due to the late date of death at T1, and 11 were not processed in the analyses due to technical difficulties. The number of completers (i.e., participants who had sent in both the first and the second questionnaire) was 233,2 rendering the effective attrition rate at 11.4%. Dropouts refer to the 30 participants whose T2 questionnaires were not received or included in the final, main analyses (comparisons were made between completers and dropouts, see Results section).

Questionnaires

Initially, the entire research team worked together to develop the T1 questionnaire, focusing mainly on the construction of a list of the key components of the cremation, and identifying major issues which can arise for a family as they face planning a cremation.

The T1 questionnaire consisted of four sections. The first section gathered demographic information, including factors which were seen as having a possible influence on decision making, such as income, education, religious commitment, and whether the participant had sought professional help in coping with their bereavement. The second section sought information about the deceased and the loss, addressing age, gender and cause of death, as well as the nature and perceived quality of the relationship between the deceased and the respondent. The third section addressed the funeral arrangements. This section addressed factual information as well as main aspects of the decision-making process and the respondent’s evaluation and feelings about the cremation, as well as possible regrets about the decisions that were made. The final section addressed the respondent’s experience of grief and grief-related health and other related psychological phenomena.

The T2 questionnaire contained changes in background situation since T1, a series of additional questions about the funeral ceremony and changes in the evaluation of the decisions surrounding the ceremony. The final section of the initial questionnaire was an integral part of T2, except for additional positively phrased items which were added, since participants commented on the T1 questionnaire having been slightly distressing.

The following measures are central to addressing the specific research question:

Components of the Cremation

An extensive series of questions covering relevant aspects about the cremation was compiled specifically for the purpose of this study by the research team. This covers the factual specifics of the cremation ceremony, interpersonal harmony/conflict in the decision-making process and overall satisfaction as well as satisfaction about specific components of the ceremony.

The category direct cremation (DC) was of special interest. DC was defined as the situation in which there was no attended service at the crematorium (with or without committal) and no service elsewhere with the coffin.

Inventory of Complicated Grief-Revised

The Inventory of Complicated Grief-Revised (ICG-r) is a 30-item measure of grief manifestations. The ICG-r has shown adequate psychometric properties (Prigerson & Jacobs, 2001). Items represent separation distress symptoms (i.e., longing/yearning for the person who died), cognitive and emotional symptoms (including difficulties accepting the loss, avoidance, bitterness/anger), and functional impairment symptoms. The participants rated the occurrence of grief manifestations in the previous 3 weeks on 5-point scales ranging from 0 = never to 4 = always. The items were summed to form an overall grief severity score.3

Participants

Demographic Background

The sample of 233 participants with complete data had a mean age of 64 (SD = 11), ranging from 20 to 88 years of age: 159 (69%) were female and 72 (31%) male (in 2 cases gender was not revealed). At T1, a total of 115 (50%) were married or lived together, 86 (37%) were widowed, 11 (5%) were separated or divorced, and 19 (8%) were single. Although most participants (224, 96.1%) reported no change in their marital situation between T1 and T2, 5 (2.1%) became widowed and 2 (0.8%) divorced or became single, and 1 (0.4%) participant married.

The mean number of people living with the participant at T1 was 0.8 (SD = 0.9), ranging from 0 (43%) to 5 (0.4%). Most people (n = 111, 47%) shared a household with their partner, 45 (19%) with children, or with parents (n = 5, 2%), while 6 (3%) lived together with other relatives.

The majority of the participants (n = 148, 64%) considered themselves Christian. The second largest group (n = 53, 23%) said they had no religious affiliation, while some said they were agnostic (n = 7, 3%), atheist (n = 10, 4.3%), or humanist (n = 9 4%). Only 3 (1%) were Buddhist and none were Muslim (cremation is not a tradition within Muslim communities).

The highest level of education was some secondary school for 4 participants (2%); completed secondary school for 51 (22%); some college or university for 36 (16%), a college or university degree for 60 (26%), postgraduate degree for 28 (12%), and other professional qualifications for 52 (23%). Regarding the work situation, the majority (n = 142, 61%) was retired. A total of 43 participants (19%) were employed full-time, 30 (13%) part-time, and 9 (4%) were self-employed. Very few (n = 7, 3%) were homemakers and 1 (0.4%) was disabled. Between T1 and T2, a vast majority of 203 participants (87.1%) reported no change in their work situation. A total of 12 participants became retired (5.2%), while 14 (6%) became employed and 1 (0.4%) started a study.

Annual household income was divided in three categories: low (less than £26,000), middle (between £26,000 and £46,000) and high (higher than £46,000) on the basis of creating more or less equal size categories. Moreover, 42.2% fell in the low-income category, 31.8% in the middle category, and 26.0% in the high-income group. Of the low-income group, 39.5% suffered a drop of income after the loss, 37% did not face any change, while 23.5% saw the income increase after the loss. Of the middle-income group, these percentages were 23%, 52.5%, and 24.6%, respectively, and for the high-income category percentages were 14%, 56.0%, and 30.0%. The higher the income, the smaller the chance of suffering a decrease in income after the loss and the higher the chance of a financial increase after the loss, χ2(4) = 11.5, p = .021.

The Loss

The mean age of the deceased person was 81 (SD = 12), ranging from 30 to 102 years of age. The gender of the deceased person was almost evenly spread with 118 (51%) female and 113 (49%) male. In two cases, the gender of the deceased person was not revealed. Death occurred between August 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017. Cause of death most frequently was a longer illness (n = 140, 62%), followed by sudden illness or health problems (n = 65, 29%). Accidents caused the death of 4 of the deceased people (2%), while homicide and suicide both occurred only once. Some (n = 16, 7%) mentioned other causes, like negligence or multiple conditions causing death.

Most often, it was one of the parents of the participant who had died; for 79 participants (34%), it was the mother; for 38 (17%), it was the father who had passed away. In another 35% (n = 82), the partner had died; husbands for 58 participants (25%) and wives for 24 (10%). For 7 participants (4%), the deceased person was a sibling (4 brothers [2%] and 3 sisters [1%]). In 5 cases (2%), a child had died, which was in all cases a son. In addition, the death of 2 (1%) grandmothers and 2 friends (1%) were the reason for participation in the study. For 16 (7%) participants, the relationship was an aunt, uncle, cousin, in-law, or step-relative. Most participants considered themselves to have (had) a very close relationship with the deceased person (n = 201, 87%). Moreover, 24 (10%) participants considered themselves somewhat close and 6 (2.6%) said they were not very close (at all). Two participants did not report their level of closeness to the deceased person.

In 90% of the cases (n = 202), the participant was considered to be the next of kin of the deceased person.

The Cremation Service

A total of 19 (8%) of the participants signed the funeral contract on behalf of somebody else, mostly because of poor health (n = 11, 5%) or for practical reasons (n = 7, 3%). In 14 cases (5%), the primary bereaved person was too weak (n = 7, 3%) or too distressed (n = 6, 3%) at the time. In one case, there was no known relation. Slightly above a third of the participants (n = 81, 35%) managed the financial funeral arrangements themselves, 17 (7%) together with others, while in 6 cases (3%), others fully took care of the funeral arrangements.

Of the 233 participants who answered the questions about the cremation service, 216 (93%) made mention of a regular service at the crematorium with (n = 206, 88%) or without (n = 8, 3%) the coffin present, or elsewhere with the coffin present (n = 30, 13%), while 17 (7%) reported not to have organized such a service. The latter qualifies as an unattended or direct cremation in the original meaning of the word. This involved seven deceased partners, eight parents, and two other relationships.

Comparison of Completers and Dropouts

When compared to completers, dropouts showed no differences in age, t(258) = .100, p = .920, gender, χ2(1, 261) = 0.058, p = .810, and number of cohabitants, t(261) = −1.039, p = .300. Fisher’s exact test showed no differences in marital status (p = .086), educational level (p = .191), income (p = .165), financial change since the loss (p = .583), nor religion (p = .274). There was a significant difference in work situation between the completers and dropouts (F = 11.3, p = .029), which is mainly due to disabled, self-employed, and part-time employed dropping out relatively more. With regard to the characteristics of the deceased, the two groups showed no difference in age, t(257) = 0.031, p = .975, and gender, χ2(1, 261) = 0.012, p = .911. Fisher’s exact test showed no differences in type of kinship to the deceased (p = .428), closeness to the deceased (p = .135), nor cause of death (p = .815). At T1, no significant differences were found either in level of grief (p = .998) between completers and dropouts. The general conclusion that emerges from these findings is that there are no major differences between those who dropped out of the study after T1 and those who completed it.

Results

Levels and Changes in Grief Over Time

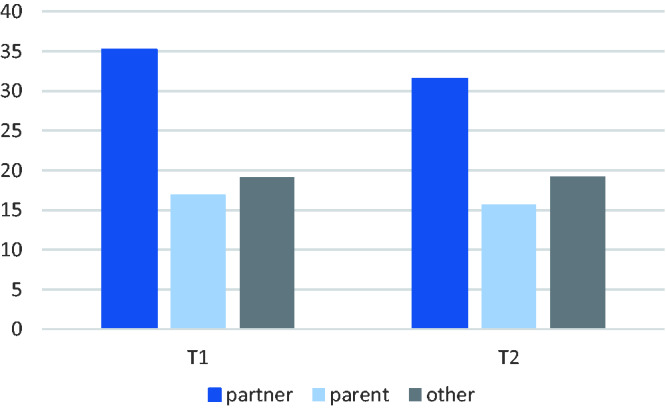

Levels of grief decreased modestly but significantly over time from an average of M = 23.6 (SD = 21.2) at T1 to M = 21.6 (SD = 19.6) at T2—Wilks = .97, F(214, 1) = 6.34, p = .013, = 0.03. These mean scores represent an on-average relatively low (normal) level of grief among the participants at both data collection points. Female participants reported an approximately 5-point higher but not significantly differing, F(1) = 3.2, p = .08 (=0.015), level of grief both at T1 and T2. These levels decrease for men and women in similar ways—Wilks λ = 1, F(214, 1) = 0.051, p = .82, = 0. There were no age differences (age groups 60 years and younger, 61–69 years, and 70+ years) in reported level of grief or change in level of grief. Grief was highest over loss of the partner (a considerable excess), compared to parents and other losses (e.g., children, siblings, grandparents, and friends-categories too small to be analyzed separately), F(2) = 21.2, p = .000, = 0.165. And although Figure 1 does suggest grief levels decreased mainly among participants bereaved of their partners (both married and unmarried and living together), this interaction does not reach significance—Wilks = 1.84, F(215, 2) = 1.84, p = n.s.

Figure 1.

ICG Scores by Lost Relationship.

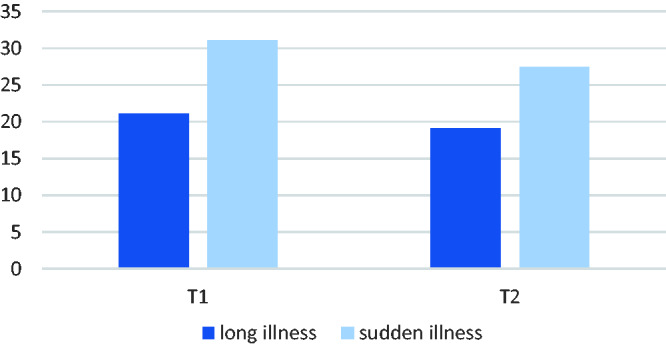

In terms of causes of death, only losses due to long term illness and sudden illness were compared, since other causes of death were too rare among the sample. Participants bereaved through sudden death scored substantially higher on the ICG both at T1 and T2, F(1) = 9.905, p = .002, = 0.049, and decreased in similar ways over time (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

ICG Scores by Cause of Death (Long vs. Sudden Illness).

We further analyzed possible effects of income and income change on levels and course of grief. This indicated no main effects due to income level, but did result in a main effect of change in household income on grief, indicating highest levels of grief at both T1 and T2 for those encountering income decrease, F(2) = 4.22, p = .016. However, no interaction was found of level of income and changes in income after the loss on level or course of grief, suggesting that the effect of income change on grief was rather similar for all three income groups.

Traditional Versus Direct Cremation as Predictors of Grief

Comparing levels and course of grief between those who had a service at the crematorium or elsewhere with the coffin present and those who had a direct cremation, the former reported mean scores of 22.9 (SD = 21.6) at T1 and 21.0 (SD = 19.7) at T2, while the latter reported 20.1 (SD = 15.8) and 17.7 (SD = 14.7), respectively. Neither the main effect of cremation service—F(1)=0.939, p = .54, =0.002—nor the difference in course turned out to be significant—Wilks F(1, 216) = 0.029, p = .866, = 0.000.

Looking at relevant background differences between DC’s and traditional cremations (e.g., age participant, age deceased, relationship with and closeness to the deceased, cause of death [e.g., long illness vs. sudden illness death] income, income change), no significant differences were found.

Decision Making Regarding the Funeral

Interpersonal Conflict

Most respondents found the process of decision making in the context of family and friends to be smooth; that is, there was little indication of conflict among the close persons involved. The five questions in T1 addressing this issue did not comprise a reliable scale, but looking at individual item level, it turned out, for example, that agreement about funeral arrangements was very high: 95% reported that friends and family were quite/very much in agreement and some 80% considered the planning smooth for those involved. Only higher levels of stress and tension in relationship to family and friends was positively correlated with level of grief at both T1 (r = .33, p = .000) and T2 (r = .30, p = .000).

Viewing of the Body

Participants were asked at T1 whether they chose to view the body. A total of 86 (38%) of the 227 having answered this question reported having viewed the body, while 141 (62%) did not, of whom 3 did not because it was not possible and 3 did not know whether it would have been possible. For only very few participants was it regarded as difficult to arrange viewing (0.9%). The motivation for viewing or not viewing the body was to preserve the memory of the deceased (4.0, SD = 1.5 on a 5-point Likert-type scale) and second for saying goodbye (3.9, SD = 1.6) for 124 participants were motivated by the wish to say goodbye in one’s own way. Other reasons reported were worries about not being able to remember the deceased if the participant did not view (2.7, SD = 1.8), and worries about regretting it if one would have decided not to view the body (2.6, SD = 1.8). Obligation, social pressure and religious beliefs hardly played a role in the decision whether or not to view the body.

Partners who viewed the body reported higher levels of grief than partners who did not want to view the body even though that was possible, both at T1 (74.6, SD = 24.5) versus 60.0 (SD = 18.2), t(57.5) = 2.9, p = .006) and T2 (68.2, SD = 20.0) versus (57.3, SD = 16.9), t(74) = 2.6, p = .01. For those participants who lost a parent, viewing the body was not related to level of grief at T1 or T2. Satisfaction with the decision to view the body was not correlated with grief at T1 and T2 either (r = .01 and .02, respectively).

Disposal of the Ashes

At T2, participants were asked about arrangements regarding the ashes, which were answered by 233 participants. Arrangements were made to bury or scatter the ashes with friends and family present by 69.7% (n = 109) of the participants, followed by 25.7% (n = 56) where the ashes were still retained by the family, and for 19.7% (n = 43), the ashes were scattered or buried without the presence of family and friends.4 For 10 participants (1%), another arrangement was made or the participant did not know what was done with the ashes. Confined to a comparison of the first three groups, level of grief differed between the groups, both at T1 and T2, F(2) = 4.40, p = .14, with grief being highest for the participants, where the ashes were still retained by the family. Changes over time in grief followed a similar pattern for all three groups (Wilks λ = 0.978, F(2, 192) = 2.11, p = .123, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Level of Grief by Arrangements for the Ashes.

|

T1 |

T2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Arrangements for burial or scatter ashes with friend/family present | 19.6 | 19.3 | 17.7 | 17.7 |

| Arrangements for burial or scatter ashes without friend/family present | 16.5 | 17.2 | 16.5 | 18.7 |

| Ashes still retained by family | 29.0 | 23.2 | 24.8 | 20.8 |

Other aspects of the funeral ceremony were not investigated further in view of the patterns found for the aforementioned more obvious variables and given the need to be cautious about capitalizing on chance.

Satisfaction With the Funeral

This T1 scale contains seven items on a 5-point scale (α = .70). Examples of items are: “I felt the service was personal and appropriate for the person who died” and “I found the service helpful and/or consoling.” The range of the scale is 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction.

Participants turned out to be on average very happy with the funeral service. Mean score was 31.1 (SD = 4.1) on a scale of 35 maximally. Two thirds scored higher than 30 with nearly a quarter scoring the maximum amount. Level of satisfaction with the funeral turned out not to be related to levels of grief at T1 (r = −.02) or T2 (r = −.02). Comparing relatively low scores (29 and lower) with high scores (30 and higher) did not result in any differences in level of grief at T1 or T2 either. The separate specific item covering the overall satisfaction with the cremation day itself revealed no relationship with level of grief either (T1: r = .08; T2: r = .06).

Discussion

We set ourselves the specific goal of examining the relationship between aspects of cremation and levels of grief over time. The results suggest that there are no particularly outstanding, notable or impactful relationships between aspects of cremation and levels of grief, nor in relationship to changes in levels of grief over a period as long as 1 year subsequent to the first time of investigation. The worry of funeral poverty, that bereaved persons would suffer more intensely as a result of cuts in ceremonial activities, has not been confirmed in this study. In this respect, the bereaved persons’ needs seem to have been well-met by the available offers of the funeral service providers. Among our participants, the majority was (very) positive about the funeral arrangements, whatever way they had organized the cremation service. Yet, any differences (and these were sufficient for investigation) in the actual arrangements or in the appreciation of different components of cremation, turned out to be unrelated to grief. The cremation ceremony itself was generally considered a meaningful and positive part of their arrangements for disposal of the body, but their specific, more or less positive evaluations were quite independent of personal reactions to loss of the close person. Importantly, although partners were grieving more intensely over their losses than adult children who had lost a parent, there were hardly any differences between these groups in how dimensions of cremation were related to grief. Yet one difference stood out: we noted that partners who viewed the body facilitated by the funeral director had higher T1 and T2 grief scores than those who chose not to (a difference not found for parents). Could it be that this funeral option provided the opportunity for those still grieving more intensely to take leave, to say goodbye? If so, this finding may again reflect the fact that the options available fit the needs of different subgroups of the bereaved clients.

In broader perspective, changes in provision of funeral services in this western society seem in line with contemporary needs of bereaved people: nowadays more options are available (and constantly developing). Our results showed that bereaved participants made use of a range of services, from those involving minimal to very extensive ceremonies. Reasons for making choices with regard to ceremonies are undoubtedly multiple and complex. But perhaps people (at least those subgroups represented by our participants) feel more freedom to make arrangements for disposal of the body in their own way these days. One could speculate that there may no longer be so much stigma to holding a minimal ceremony (in so far as it is well organized and conducted and not appearing to be cheap). On the other hand, there is evidence from funeral cost research that people still over-stretch themselves financially in selecting body disposal choices that they feel appropriate (Corden & Hirst, 2013b). We still have much to learn about the motives underlying choices in the face of diverse contemporary options.

There is no doubt that funerals serve many functions for bereaved persons, in keeping with the fact that such customs are incorporated into nearly all cultures of the world and across historical periods (cf. Hoy, 2013; O’Rourke et al., 2011). However, in terms of research findings, the results of our study endorse the recent conclusion of Mitima-Verloop et al. (2019) that, despite the intuitive assumption that funeral dimensions also contribute to grief adjustment, there is actually little association between aspects, perceptions and evaluations to do with the cremation and grief. That these results indeed indicate the relative unimportance of funeral components among risk factors for grief, also comes indirectly from findings that our participants did differ according to other, well-established risk factors, showing differences in directions typically found in reviews of the literature (e.g., sudden death or loss of a partner were associated with more intense grief over time than the relevant comparison groups).

A strength of this study is that the participants may be regarded as representing a normal segment of the population (naturally limiting the sample to those with a cultural background/tradition of cremation), as illustrated, for example, in the sociodemographic and grief-level details included in the Results section. As such, they seem to be rather typical of the range of clients encountered by funeral service providers. However, a minority of bereaved persons (approximately 10%, cf. Lundorff et al., 2017) suffer from complications in their grieving process. Our investigation did not focus specifically on this subcategory. It is possible that an important source of difficulties for a client diagnosed with complicated grief could relate back to adverse funeral events (e.g., if the disposal of the body were to be perceived as going severely wrong). Further investigation is needed to establish the extent to which such aspects play a part in complicated forms of grieving. Our results may also apply only to the type of western culture in which our study took place and not extend to those with very different funeral customs and rituals. They also relate to the free choices made by the bereaved and may not apply to situations such as a pandemic or other large-scale disaster, when the type of funeral may be imposed by circumstances or by government.

A weakness of the study is the low Time 1 response rate. Nor was it possible to compare participants and refusers, since for privacy reasons, we did not have any background information about the bereaved persons invited to participate in the study. The sample size did not permit unlimited analyses of subgroups of participants. Larger-scale studies need to replicate this investigation, extending to examination of potentially vulnerable subgroups (e.g., the impact of children’s attendance at funerals on grief over time). Nevertheless, we were able to compare groups according to their different choices and decisions regarding components of cremation. Furthermore, the extremely low attrition rate from T1 to T2 can certainly be considered a strength too, with the final sample size enabling us to conduct the statistical analyses we consider essential for addressing the research question.

A general cautionary remark is in order, about making inferences of causality. Even though few relationships and differences turned out to be significant, we need to be careful in interpreting any (lack of) differences in psychosocial functioning related to aspects of cremation in terms of causality. The study by Banyasz et al. (2017) on the use of bereavement-related services more generally is illustrative. Persons with depression and complicated grief reported greater willingness to use specific services such as a memorial website than those without. But: does one look at a memorial website a lot because one has these symptoms, or are these symptoms due to/intensified because of the (ruminative?) activity of looking so much at such websites?

Bereavement has been established as a life event associated with major, negative effects on mental and physical health and well-being (Stroebe et al., 2016). Research is needed to understand precisely who is most at risk, and in the current context, to establish whether vulnerability was related to arrangements/choices made for disposal of the deceased’s body. This study was designed in the first place to inform policy makers and the funeral industry of possible impacts of changing cremation practices on bereaved persons. The results are on the one hand reassuring, but on the other hand, need replication and extension in the ways suggested earlier. Nevertheless, in due course, dissemination of knowledge from such projects should be able to guide policy and potentially contribute to the adaptation of bereaved people over time.

Finally, what is the (tentative) take-home message at this point in time? We noted in the Introduction that concern to investigate the research question about the connections between components of cremation and adjustment to bereavement was fuelled by the possibility that providing a wider range of (more minimal) services could potentially have a negative rather than the intended positive consequence for bereaved persons. We did not find this to be the case. Not only were there no systematic patterns of results indicating negative, harmful associations between dimensions of cremation and levels of grief over time, but clients seem to appreciate the available offers currently provided by the funeral services covered in our investigation, and to be able to use the available options in various ways, according to their personal preferences and needs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to DignityUK for funding this project and especially to Simon Cox, Head of Insight and External Affairs of DignityUK, for facilitating this research project in many ways.

Author Biographies

John Birrell: is a visiting research fellow at the Centre for Death and Society at the University of Bath. He has been actively involved in the development of bereavement care in Scotland for over 20 years and is an educator and policy consultant. His recent work has focussed on funeral policy and the need for support with costs for those on low incomes.

Henk Schut: is associate professor of Clinical Psychology at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. His research interests cover processes of coping with loss and the efficacy of bereavement care and grief therapy. He also supervises post-academic clinical psychologists in their research interests. With Margaret Stroebe he developed the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement.

Margaret Stroebe: is professor Emeritus, working at the University of Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands. She has specialized in the field of bereavement research for many years, collaborating with colleagues on theoretical approaches to grief and grieving, reviewing the scientific literature (e.g., in 3 handbooks), and conducting empirical studies (e.g., interactive patterns of coping).

Daniel Anadria: is an Excellence Programme BSc Psychology student at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands, with a previous publication in Psychiatric Quarterly on PTSD rates in therapists treating violent patients. He also works in the private sector as a data analyst. He hopes to follow an academic career after finishing his studies.

Cate Newsom: is a visiting research Fellow at the Centre for Death and Society at the University of Bath. She holds a PhD in clinical psychology from Utrecht University, where her research in the field of grief and trauma investigated the effectiveness of bereavement counselling interventions and care in the community.

Kate Woodthorpe: is a senior lecturer in Sociology in the Centre for Death and Society, Department of Social and Policy Sciences, University of Bath. She has conducted research on funeral practices and costs, mortuary services and cemetery usage. She has acted as special advisor to the UK Government on funerals.

Hannah Rumble: is a research fellow at the Centre for Death and Society, University of Bath. She is also a member of the editorial board for the journal Mortality and European Research Network on Death Rituals.

Anne Corden: is an honorary research fellow at the Social Policy Research Unit, University of York, UK, where she has many years’ experience of qualitative social research. Her work has spanned policy research in areas of income maintenance, health and welfare, and services for families and children. Most recently she has led a stream of research on experience of bereavement, with particular focus on the economic implications.

Yvette Smith: is research manager at Dignity Funerals, U.K. Dignity Funerals is a British run company; it is a large provider of funeral services and prepaid funeral plans in locations across the United Kingdom.

Notes

The literature search (using terms: Cremation or Funeral or Burial or Body disposal), conducted in 2017, identified 1,113 articles (book sources were searched by hand). Screening reduced the scope to approximately 70 articles, of which roughly 25% addressed the specific topic of funerals in relationship to adaptation. A search update in November 2019 yielded 51 new articles, of which 3 added particularly to this knowledge; one additional, highly important article was included subsequently.

Based on an expected overall difference over time of multiple indices of well-being, health, and functioning, a theoretically expected medium effect size (f2 = .15) for multiple linear regression analyses, and α and β of both 5%, the necessary number of participants with complete data for the project was 231 to analyze a maximum number of 20 predictor variables with this number of participants.

Multiple indicators of psychosocial functioning (e.g., general health, social support, social and emotional loneliness, grief rumination, life changes, and self-efficacy) were included for exploratory reasons, which are not reported here for lack of statistical power but resulted in similar findings to the ones presented.

Participants sometimes endorsed more than one subcategory within the 3 constructed groups, therefore the percentages do not add up to 100%.

Author Contributions

J. B., H. S., and M. S. developed the study concept. J. B., H. S., M. S., C. N., K. W., H. R., A. C., and Y. S. derived the empirical testing procedure. J. B., H. S., M. A., C. N., K. W., H. R., A. C., and Y. S. facilitated collection of the data. H. S., M. S., and D. A. processed the data and drafted the manuscript, with substantive expertise from J. B., C. N., K. W., H. E., A. C., and Y. S. All authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research question has been formulated in close collaboration with DignityUK. The applied methods, results, and conclusions presented in this report have been established fully independently of the funding agency. Co author Y. S. of DignityUK facilitated the study by providing necessary data-access (confidentiality being observed), but did not participate in the design, analyses, or interpretation of the data.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research project was funded by DignityUK, Sutton Coldfield, UK.

ORCID iDs

Margaret Stroebe https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8468-3317

Hannah Rumble https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5410-8194

References

- Banyasz A., Weiskittle R., Lorenz A., Goodman L., Wells-Di Gregorio S. (2017). Bereavement service preferences of surviving family members: Variation among next of kin with depression and complicated grief. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 20, 1091–1097. 10.1089/jpm.2016.0235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard V. R., Burger W. C. (2017). Change and innovation in the funeral industry: A typology of motivations. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 75, 47–68. 10.1177/0030222815612605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard V. R., & Burger W. (2020). Selling in the dying industry: An analysis of trends during a period of major market transition in the funeral industry. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 80, 554–567. 10.1177/0030222817745430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell J., Sutherland F. (2016). Funeral poverty in Scotland: A review for Scottish Government. Citizens Advice Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton C., Camp D. J. (1987). Funeral rituals and the facilitation of grief work. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 17, 343–352. 10.2190/VDHT-MFRC-LY7L-EMN7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton C., Camp D. J. (1989). The post-funeral ritual in bereavement counseling and grief work. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 13, 49–59. 10.1300/J083V13N03_05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burke L. A., Neimeyer R. A. (2013). Prospective risk factors for complicated grief. In M. Stroebe, H. Schut, & J. van den Bout (Eds.), Complicated grief: Scientific foun-dations for health care professionals (pp. 145–161). Routledge.

- Castle J., Phillips W. L. (2003). Grief rituals: Aspects that facilitate adjustment to bereavement. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 8, 41–71. 10.1080/15325020305876 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caswell G. (2011). Beyond words: Some uses of music in the funeral setting. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 64, 319–334. 10.2190/OM.64.4.c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corden A., Hirst M. (2013. a). Economic components of grief. Death Studies, 37, 725–749. 10.1080/07481187.2012.692456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corden A., Hirst M. (2013. b). Financial constituents of family bereavement. Family Science, 4, 59–65. 10.1080/19424620.2013.819680 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson G. E. (2012). Diversity in death: Body disposition and memorialization. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 20, 141–158. 10.2190/IL.20.2.d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doka K. (2012). Therapeutic ritual. In R. Neimeyer (Ed), Techniques of grief therapy: Creative practices for counselling the bereaved (pp. 341–343). Routledge.

- Fan J. X., Zick C. D. (2004). The economic burden of health care, funeral, and burial expenditures at the end of life. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 38, 35–55. 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2004.tb00464.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamino L. A., Easterling L. W., Stirman L. S., Sewell K. W. (2000). Grief adjustment as influenced by funeral participation and occurrence of adverse funeral events. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 41, 79–92. 10.2190/QMV2-3NT5-BKD5-6AAV [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs M., Meese J., Arnold M., Nansen B., Carter M. (2015). #Funeral and Instagram: Death, social media, and platform vernacular. Information, Communication & Society, 18, 255–268. 10.1080/1369118X.2014.987152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy W. G. (2013). Do funerals matter? The purposes and practices of death rituals in global perspective. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter J. (2007). Bereavement: An incomplete rite of passage. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 56, 153–173. 10.2190/OM.56.2.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp S. W., Kemp E. (2007). The death care industry: A review of regulatory and consumer issues. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 41, 150–173. 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00072.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen P., Weisæth L., Heir T. (2012). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 75, 76–97. 10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lensing V. (2001). Grief support: The role of funeral service. Journal of Loss &Trauma, 6, 45–63. 10.1080/108114401753197468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobb E. A., Kristjanson L. J., Aoun S. M., Monterosso L., Halkett G. K., Davies A. (2010). Predictors of complicated grief: A systematic review of empirical studies. Death Studies, 34, 673–698. 10.1080/07481187.2010.496686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J., Rumbold B., Aoun S. M. (2019). Memorialization practices are changing: An industry perspective on improving service outcomes for the bereaved. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0030222819873769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O’Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 138–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus R., Schafer C. (2014). Final arrangements: Examining debt and distress. Mortality, 19, 379–397. 10.1080/13576275.2014.948413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitima-Verloop H., Mooren T., Boelen P. (2019). Facilitating grief: An exploration of the function of funerals and rituals in relation to grief reactions. Death Studies. Advance online publication. 10.1080/07481187.2019.1686090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M. I., Gino F. (2014). Rituals alleviate grieving for loved ones, lovers, and lotteries. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143, 266–272. 10.1037/a0031772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke T., Spitzberg B. H., Hannawa A. F. (2011). The good funeral: Toward an understanding of funeral participation and satisfaction. Death Studies, 35, 729–750. 10.1080/07481187.2011.553309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson H. G., Jacobs S. C. (2001). Diagnostic criteria for traumatic grief: A rationale, consensus criteria, and preliminary empirical test. Part II. Theory, methodology and ethical issues. In M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, W. Stroebe, & H. A. W. Schut (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care (pp. 614–646). American Psychological Association Press.

- Rando T. A. (1985). Creating therapeutic rituals in the psychotherapy of the bereaved. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 22, 236–240. 10.1037/h0085500 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves N. C. (2011). Death acceptance through ritual. Death Studies, 408–419. 10.1080/07481187.2011.552056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royal London. (2016). National funeral cost index report https://www.royallondon.com/siteassets/site-docs/media-centre/royal-london-national-funeral-cost-index-2016.pdf

- Rugg J., Jones S. (2019). Funeral experts by experience: What matters to them. Research Report, University of York, UK.

- Sas C., Coman A. (2016). Designing personal grief rituals: An analysis of symbolic objects and actions. Death Studies, 40(9), 558–569. 10.1080/07481187.2016.1188868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servaty-Seib H. L., Hayslip B., Jr. (2003). Post-loss adjustment and funeral perceptions of parentally bereaved adolescents and adults. OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 46, 251–261. 10.2190/UN6Q-MKBH-X079-FP42 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Folkman S., Hansson R. O., Schut H. (2006). The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 2446–2451. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H. (2016). Overload: A missing link in the dual process model? OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 74, 96–109. 10.1177/0030222816666540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Cremation Society. (2019). Progress of cremation in the British Islands 1885-2018 https://www.cremation.org.uk/progress-of-cremation-united-kingdom.

- Valentine C., Woodthorpe K. (2013). From the cradle to the grave: Funeral welfare from an international perspective. Social Policy & Administration, 48(5), 515–536. https://doi/10.1111/spol.12018 [Google Scholar]

- Vale-Taylor P. (2009). We will remember them: A mixed-method study to explore which post-funeral remembrance activities are most significant and important to bereaved people living with loss, and why those particular activities are chosen. Palliative Medicine, 23(6), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0269216309103803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter T., Hourizi R., Moncur W., Pitsillides S. (2012). Does the internet change how we die and mourn? OMEGA–Journal of Death and Dying, 64, 275–302. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FOM.64.4.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijngaards-de Meij L., Stroebe M. S., Stroebe W., Schut H. A. W., Bout J., Van der Heijden P. G., Dijkstra I. C. (2008). The impact of circumstances surrounding the death of a child on parents’ grief. Death Studies, 32, 237–252. 10.1080/07481180701881263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]