Abstract

Background:

Recruitment of participants into research studies, especially individuals from minority groups, is challenging; lack of diversity may lead to biased findings.

Aim:

To explore beliefs about research participation among individuals who were approached and eligible for the GRADE study.

Methods:

In-depth qualitative telephone interviews with randomized participants (n = 25) and eligible individuals who declined to enroll (n = 26).

Results:

Refusers and consenters differed in trust and perceptions of risk, benefits and burden of participation. Few participants understood how comparative effectiveness research differed from other types of trials; however, some features of comparative effectiveness research were perceived as lower risk.

Conclusion:

We identified facilitators and addressable barriers to participation in research studies.

Keywords: : comparative effectiveness research, qualitative research, recruitment

The successful execution of clinical trials depends on the recruitment and subsequent participation of motivated study participants. Recruitment is often challenging; it is affected by the characteristics of the study itself, including complexity, duration, the burden for participants, as well as perceived risk of the intervention and the time commitment required [1,2]. Recruitment is also affected by communication skills and rapport established between potential participants and research staff [3]. Preferences and attitudes of potential participants also play a role, such as preferences for certain treatment arms or concern over adverse effects [4]. Other commonly noted barriers include time and financial constraints, lack of child care, rigid work schedules and transportation issues [5].

In racial and ethnic minority groups, additional barriers include ineffective communication due to limited understanding of cultural backgrounds and failure to provide materials in the appropriate language or level of health literacy [3,4]. Skepticism of medical research and researchers in general, as well as distrust of the medical establishment, remain more prevalent in minority communities [4,6,7]. Distrust may be exacerbated when there is limited diversity within a research team [4]. Historical mistreatment of minority groups in research continues to pose an obstacle [5,8–10]. Together these contribute to disproportionately low representation in clinical trials of all groups other than non-Hispanic whites [11]. Limited diversity within clinical trials limits the ability to assess and address potential differences in response to therapeutic approaches. Identification and inclusion of under-represented groups is especially important to make inferences of study results to all affected populations.

There is growing a appreciation that comparative effectiveness research (CER) may help to address important gaps in evidence [12]. CER studies aim to compare the benefits, risks, and sometimes costs of healthcare interventions in settings that are more typical of the real world and to provide evidence that can be applied to typical patients more rapidly than has been the case for many clinical trials. Inclusion of underserved and disadvantaged populations is especially important in CER studies [13]. Understanding how the public, and in particular minority populations view and understand CER is crucial, yet little is known about barriers to recruitment into such studies.

The objective of this qualitative study is to evaluate barriers and facilitators of participation in a large comparative effectiveness trial, the GRADE study, with the overarching goal of informing recruitment efforts for comparative effectiveness studies.

Methods

The parent study: GRADE

GRADE is a multicenter, unmasked, comparative effectiveness study of major classes of pharmacologic treatments of diabetes. The trial was launched in April 2013 with the goal of recruiting 5000 participants across the USA from 45 participating clinical sites. Major eligibility criteria for the study include having Type 2 diabetes for 10 years or less, age 30 years or older at the time of diagnosis, treatment with metformin only, a centrally measured HbA1c level of 6.8–8.5% at the time of randomization, and willingness to self administer daily injections if randomly assigned to one of the two injection therapies. GRADE aimed to recruit a study cohort that included, as much as possible, participants from those racial and ethnic minority groups that are disproportionately affected by Type 2 diabetes. To this end, GRADE chose some clinical sites to include locations that serve racial and ethnic minority groups, and with track records of successful minority recruitment. Recruitment involved an initial contact for prescreening via telephone by GRADE research staff. Potential study participants were informed about the purpose of the study and the treatments involved and assessed for any potential exclusion criteria. If an invitation to participate in a screening visit was accepted, eligibility was further evaluated at an in-person visit.

Participants were randomly assigned to take one of four US FDA-approved medications in addition to metformin. These medications included glimepiride, liraglutide, sitagliptin, and glargine insulin. Participants received a $100 honorarium annually in addition to personalized diabetes care and study medications free of charge. The study, once completed, will provide an unbiased comparison of these drugs over a clinically meaningful period of follow-up of 3–7 years [14]. Characteristics and mechanisms associated with differential responses to medications are also being determined and will help understand and individualize diabetes care. While the primary outcome of GRADE is glycemic control, other important patient-centered outcomes are also being studied [14].

Sample

Interview participants were sequentially sampled from individuals who had been prescreened for participation in GRADE and found to be eligible for screening, as well as individuals who had completed screening or run-in visits. Two groups of participants were defined: individuals who were prescreened or screened eligible, but chose not to participate in GRADE, hereafter referred to as refusers; and individuals who completed a screening visit and consented to begin the run-in phase of the study, hereafter referred to as consenters. The majority of refusers declined a screening visit during a prescreening call from a GRADE study site staff member.

For this qualitative study, staff members from five GRADE clinical centers identified individuals who had refused or consented within the previous 2 months. They then obtained permission for their contact information to be shared with the qualitative team. These five centers (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, MedStar Health-Baltimore, University of Alabama, University of Iowa and Massachusetts General Hospital) provided geographic diversity. Three centers included high proportions of black and Hispanic participants. Upon reaching the potential participant, the qualitative team explained the purpose of the interview and obtained oral consent before proceeding.

Interview methods

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted over the telephone. An interview guide (Table 2) was developed to explore beliefs and concerns related to medical research in general and why respondents decided to refuse or to consent to participate in the GRADE study in particular. Topics included how participants were introduced to the trial, reasons for participation/nonparticipation, previous participation and experience in research, perceived benefits or concerns, expectations regarding research, understanding of CER, and strategies that could lead to improved recruitment. Participants received a gift card of $20 value for completing the interview. English language interviews were conducted by a research fellow (n = 42); a bilingual research assistant conducted nine interviews in Spanish. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Spanish language interviews were professionally translated into English and transcribed.

Table 2. . Interview guide.

| Main question | Prompts |

|---|---|

| Tell me about where you go for your diabetes care? | – For how long have you gotten care there? – Describe your relationship with your doctor – Describe your perception of your diabetes care |

| Tell me about your prior experience with research | – When we talk about research, what do you think about? – Have you ever participated in a clinical research study? If yes, tell me about that. – Do you know anyone who has participated in a research study? Why do you think that person decided to be in a study? – What are some of the reasons in general that a person might decide to be involved as a participant in a study? |

| Think back to when you first learned about the GRADE study. Tell me about that experience | – What was your first thought about being in a research study? – What might be the benefit of participating in the GRADE study? – Did you have concerns about participating? What were they? |

| If you were describing GRADE to a friend, tell me how you would tell them what GRADE is all about | – What is your understanding of how GRADE will help patients and doctors in the future? – How important do you think GRADE is? – How important do you think clinical research is in general? – What is the US FDA-approved drug mean to you? |

| You decided to be/NOT to be in GRADE. What were most important things to you personally that led to your decision? | – Logistical or time concerns? – Impact on relationship with personal physician? – Sometimes people say that they do not want to be a ‘guinea pig’? What do you think that means? – GRADE is called a comparative effectiveness research study. In the GRADE study, we do not test new drugs. Instead, we are comparing four different medications that are already known to work in diabetes and that are FDA approved. We are comparing them to each other. We know that they all work, but we want to know which one works the best and in whom it works the best. CER also aims on focusing on the things that matter to patients and doctors in real life, such as convenience of taking a medication, cost or side effects. – Now that you know about CER, would you be more or less likely to want to be in this type of study? Explain |

| What would you like researchers to know in order to be more sensitive to what is important to you? |

CER: Comparative effectiveness research; GRADE: Glycemia reduction approaches in diabetes.

Analysis

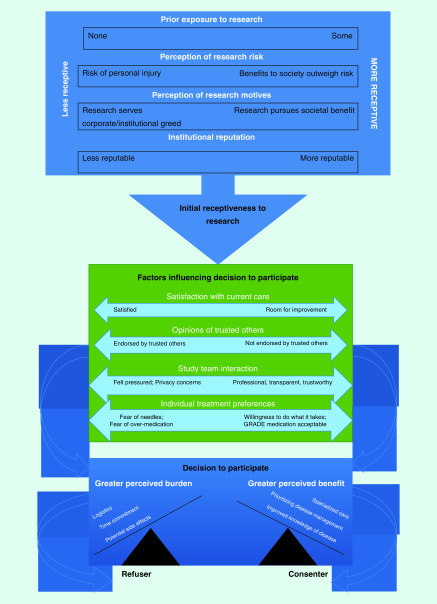

The team of analysts included two internists (S Behringer–Massera and G George), a research coordinator with public health training (T Browne) and a senior investigator experienced in qualitative research (MD McKee). Analysis was completed in two phases. The initial phase employed an editing approach [15]. Members of the team read the data closely to identify themes related to taking part in research studies, perception of the GRADE study, interactions with GRADE staff and to identify unanticipated themes. A tentative coding scheme was developed and applied to transcripts and refined by the team. The final coding scheme was then applied to each transcript by at least two coders; differences in coding were rare and were resolved through discussion. Data collection continued until no new themes were identified (data saturation). Dedoose [16] qualitative software was used to facilitate the retrieval of text passages. In the second phase, using constant comparison, similarities and differences between consenters and refusers were explored. Using grounded theory [17], we developed a model of barriers and facilitators of participation (Figure 1). To test the fit of the data to this model, each analyst reviewed every interview. We discussed disconfirming cases as a group and refined the model.

Figure 1. . Factors influencing decision to participate in research.

Results

We contacted 57 individuals; 6 declined to be interviewed, leaving 51 participants (25 consenters and 26 refusers). Of those who refused the interview, five verbally declined while one potential participant did not answer after several call attempts. None of those who declined a telephone interview were Spanish speaking, and all were refusers. We purposefully sampled to include roughly even numbers of individuals from three racial/ethnic categories (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic African–American/black and Hispanic) based on self report. Demographics of the recruited sample by clinical center are described in Table 1.

Table 1. . Demographics.

| Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx (n = 20) | Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston (n = 8) | University of Iowa, Iowa City (n = 8) | Medstar, Baltimore (n = 11) | University of Alabama, Birmingham (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): – Mean ± standard deviation – Range |

58.0 ± 11.7 32–74 |

58.1 ± 10.6 40–73 |

58.0 ± 13.9 34–78 |

53.4 ± 8.5 41–67 |

59.3 ± 8.1 50–67 |

| Study participation, n (%): – Refusers – Consenter |

13 (65) 7 (35) |

2 (25) 6 (75) |

0 8 (100) |

7 (64) 4 (36) |

4 (100) 0 |

| Race, n (%): – White – African–American – Hispanic |

1 (5) 8 (40) 11 (55) |

8 (100) 0 0 |

8 (100) 0 0 |

4 (36) 7 (64) 0 |

2 (50) 2 (50) 0 |

Interviewees from all participating GRADE sites in most cases described learning about GRADE initially via a letter from their primary care clinician followed by a phone call from a GRADE site study team member for a prescreening interview. Receptiveness of potential study participants during these phone calls varied widely. Factors associated with initial receptiveness to attend a screening visit are described below; they included how individuals perceived research in general, previous exposure to research and the perceived risk of participating in research. Regardless of initial receptiveness, a number of themes were identified that influenced the decision to refuse or to participate, including opinions of trusted others, satisfaction with current healthcare, interactions with the study team, individual treatment preferences and the perception of study burden versus benefit.

Initial receptiveness to research

Prior exposure to research

Some participants had prior research experiences, either positive or negative, which had shaped their general opinion about research. A few had participated in research themselves, had family who had participated, or were comfortable with research because they had educational backgrounds that included scientific methods.

(M = Male, F = Female, W = Non-Hispanic White, B = Non-Hispanic Black, H = Hispanic, C = Consenter, R = Refuser)

M/W/C: … I saw this study and my wife was in a study for something about lungs, maybe it was a COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease] study or something… They still do follow-up stuff with her and she got real good treatment.

Perception of research & research-related risk

The understanding, perception and importance of research in general, as well as of the GRADE study in particular, varied widely. When asked to define research and the GRADE study in their own words, responses varied. Many recalled very little about the purpose of GRADE. Some reflected a sophisticated understanding:

M/W/C: […]in addition to the metformin, which is kind of a base medication that was part of the requirement for being in the study, they were looking at four other medications that were very commonly prescribed in the diabetes treatment. And they were looking at the efficiency of those individual ones combined with the metformin.”

F/B/R: “All I can really recall at this time is it had something to do with, you know, diabetes of course, but that's all I really remember.

When asked about the importance of medical research, both consenters and refusers agreed that research and the GRADE study were very important for improvement of current medical knowledge and treatment guidelines.

M/B/C: I think that clinical research is very important. The only way we can advance in clinical medicine is through research.”

M/W/C: “You know, I come from a science and engineering background and I know how important it is to have good research to back up your decision… Yeah, so I would rank it a big deal. You know, for me the whole scientific establishment is kind of an important thing that people hopefully collectively understand… As a good society.”

F/B/R: “I look at it like I'm just open to (research) because I want better. I want better for myself and other people around the world.

Consenters typically saw research as a direct way to influence and improve their future and the well being of their families and communities. Many refusers also regarded research as important, but they did not want to be the subjects from which others learned. This refuser was concerned about personal risk of injury:

M/H/R: You can’t buy a kidney at Walmart, you know what I mean, so I know that everything is research and that research is important, but again my life is important too.

In contrast, this consenter emphasized benefit to others:

M/W/C: And, you know, again this is data and research and information that will help somebody else not have a problem. If I help with this, somebody else won’t have a problem because we’ll have good data and they’ll be able to make a better choice about what to use and what the side effects are and how easy it is to do…

Risk & CER

Most participants had little familiarity with clinical research designs and with CER in particular.

W/M/C: That’s probably the first time I’ve ever paid any attention to it. I’ve heard of research but I never really got into it or interested enough to bother to find out how they were doing it.

When we described CER, most participants indicated that such designs would positively influence participation, perceiving CER as lower risk compared with other types of clinical research.

M/B/C: The fact that these drugs were already on the market eased, you know, eased the anxiety I might have had […]”

M/W/C: “And (the meds) were already tried and true. They had been using them; they knew they were good.

For others, concern about potential risks still outweighed the fact that approved treatments were being compared:

F/B/R: Well, yeah, there’s a risk… if something goes really bad with a bad reaction or something cause you hear about all the side effects and what could happen and you never know. I could be that one person that it happens to.”

M/H/R: “But you know that with these trials there’s no safety net. I mean you’re doing this at your own risk.

Perceptions of motives of researchers

Not surprisingly, more refusers expressed distrust about research and had more negative views of research than consenters. For some, these views were shaped explicitly by historical events such as the abuses of Tuskegee, which was mentioned by participants in two out of five contributing sites.

M/B/R: First thing that kind of come to my mind is many, many years ago black men were used in a survey for syphilis and were injected with syphilis; I believe that was in Tuskegee, Alabama, and me being a black man I was skeptical of becoming a guinea pig.

Others had pervasive concern about potential exploitation by government:

M/W/R: You know, now you’re a diabetic, all stemming from dioxin poisoning from Agent Orange in Vietnam exposure (…), so our government’s allowing us to die. Why would I want to volunteer for a research that has anything to do with my condition because of what they did?

For others, concern about exploitation was more explicitly related to perceptions of the motives of researchers:

M/W/R: And behind much of science, you know there isn’t specifically use for university, just corporate greed.”

M/W/R: “So I think that there is some suspicion of science as being cold and uncaring. Even though that’s not how I see it. Or, that they have ulterior motives, like the pharmaceutical industry. You know, while a lot of the research is groundbreaking the first and foremost thereabouts are returns to the shareholders.

Influences on the decision to participate

Participants reported a number of factors that influenced their decision making. These factors could influence an individual with low initial receptiveness to research to attend a screening visit, or ultimately to consent to participate. Conversely, in some cases, one or more of these factors influenced a participant to refuse even if initial receptiveness to research was high.

Trusted others

Participants sometimes sought the opinion of primary care providers (PCPs), family or other authority figures prior to enrolling in GRADE. For some, positive or negative reinforcement strongly influenced their final decision. In some cases, PCPs spoke directly to patients about the benefits of GRADE, which was very powerful.

F/W/C: My primary care (provider) recommended that I try to be a participant in the research, in the GRADE study, and she was very specific that I try out for it and she recommended me highly for it.”

M/W/C: “I was going in for my annual physical and I discussed it with the doctor that I was thinking about entering the program and he said that he thought it was a good idea.”

M/H/C: “I asked one of my bosses and I told him about you guys, I gave him your number and everything, and he did some research as well. He researched and told me “they’re from the diabetes (center) and they’re going to give you various pills and all of that, …. I also asked my main doctor…

For many, even if not discussed, letters signed by the PCP provided a sense of trustworthiness and legitimacy of the GRADE study. Negative feedback from PCPs – cited by a few – almost always was associated with refusal to proceed with GRADE.

M/B/R: He said that I come to him anyway four-times a year for my check up and he was basically saying that you know, we’re doing the same thing basically what they want to do with you”.

M/B/R: “(…) at first I said yes, so I would like to be part of the study but then, like I said, I had an appointment with him maybe a few days after that and that brought that to (my doctor’s) attention, he said I didn’t need it. So that pulled me out from the study. If I didn’t go see him, I would have did the study.

Satisfaction with current care

Most, but not all potential participants also had existing relationships with primary care. In some cases, overall satisfaction with their current care was a disincentive to participate in GRADE.

F/H/R: I was doing fine with my doctor. He was treating me well and I was doing well. So, I didn’t see any need.

Influence of the study team & institution

The quality of interaction with the study team was critical in establishing a relationship with the potential participant. Interviewees reported several positive attributes that were influential. These included professionalism of the staff, good communication, individualized and personalized approaches in care, trustworthiness and transparency. Many participants recalled details about their first experience and interaction with the study staff better than details of the study itself. Positive aspects of these interactions included friendliness, patience and compassion of the staff. A sense of connection with the study team followed positive interactions and was associated with receptiveness of the participant to learn more about the details of the study.

M/H/C: Well, first it was because of the person who took care of me. That was one of the first things. Here, everything is very personal and individual. A very good doctor treated me.”

M/H/C: “When I go I feel like I’m in the family…. I know that I can talk… about anything at all that is bothering me even if it has nothing to do with diabetes.”

M/W/C: “The research team seemed like very good best-of-the-bunch type of people. I don’t have one negative thing I would want to say about any of them. You know, they seem to have some of the best nurses in the hospital system working there, for crying out loud. Very skilled.

In a minority of cases, initial interactions were off-putting and to some felt like an invasion of privacy:

M/H/R: Well, I kind of felt like my privacy was being invaded because the only people who know about my diabetes are my doctor and myself.”

F/B/R: “You never know what type of questions they’re going to ask and (…) I’m just not crazy about discussing everything with everybody (over the phone).

Perception of the sponsoring institution was also a factor for some in their decision to participate in GRADE.

M/W/C: I think probably the fact that this was being done by a well-respected university medical center, you know, I think that adds to its legitimacy.”

M/W/C: “One of the benefits I knew I would receive from the study is I would be working with an internationally known institution.

Individual treatment preferences

Individual traits that were associated with receptiveness or lack of receptiveness to participate in GRADE included preferences for diabetes management, and various degrees of aversion to risk. Both consenters and refusers often expressed a dislike for taking additional medications to treat their diabetes for fear of being unnecessarily overmedicated.

F/B/R: It’s just that some things I’m afraid of, like taking on another medicine.”

F/H/C: “I don't want to overburden my body with so much (medicine) because then my body is going to feel addicted.

The idea of using injections was viewed as particularly problematic for many potential participants; not surprisingly this was more common among refusers.

M/B/R: Well … she told me that there were four different kinds of medicines they were going to be using. She said two of them were pills and two of them were injected and I told her that if I had to stick myself twice a day, then count me out cause I don’t like needles.

In addition to concern about needles, some were specifically opposed to use of insulin:

M/B/R: If I had it that bad where I had to start going on insulin, you know, I’m sure I would rather than die, but it'll be a have-to thing.

Perceived benefit versus perceived burden

Potential benefits cited by participants included gaining a better knowledge of their disease, improved motivation for self care, prioritizing management of the disease and accessing cutting edge specialized and personalized care. Some participants articulated a care-related need or a perceived benefit that influenced their openness to be in the GRADE study.

M/W/C: (…) it just seemed like at the time my diabetes was sort of spiraling out of control and that I wasn’t being very good and I saw this as a way to get on track.”

M/W/C: “You know, I think for me that the biggest benefit it’s going to allow, is going to force me to better keep my blood sugars under control.”

F/H/C: “I kept thinking, I’m only taking 500 mg (of metformin) and it’s not that I have it super high but I also haven’t brought it (my A1c) down. Let me accept this study because I felt, maybe at least they had another medication, or they’ll do another lab work up more in depth or maybe I need something different.

Individuals ultimately made the decision to participate after evaluating whether the burden of participating in GRADE was acceptable or too high. Areas of burden unrelated to the treatment itself included the logistics of integrating participation in a research study into everyday life (e.g., time constraints, obligations at work, travel).

M/W/R: How am I going to participate in a study (…) when I’m running a business during the day?”

F/H/R: “But it’s so far away, like an hour and a half away. If someone could come to me, that would be so much better. Really, I just wish that the treatment center could be closer…

Discussion

Prior studies have identified barriers to research participation, but unlike the present study, few have used qualitative methods to explore decision making [18,19], and none have obtained perspectives about research participation in the context of a comparative effectiveness study from both consenters and from individuals who were eligible but declined participation. The design of GRADE – a comparative effectiveness study that only used FDA-approved diabetes drugs – was explored during the interviews. Nearly all respondents in this qualitative study were unaware of how CER differed from traditional clinical trials and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this topic. Participants nonetheless had opinions about the use of FDA-approved drugs. A study that compares FDA-approved drugs was generally perceived as ‘safer’ compared with other ‘experimental’ research trials. For some, this increased trust and decreased the perceived risk of participation. This is consistent with a previous finding that use of FDA-approved drugs sends a message of safety and efficacy regarding the use of a drug and increases acceptability [20]. Our study, however, is novel in providing some information about how a comparative effectiveness design may impact a potential participant’s decision to participate in a clinical trial. Thus, our study suggests that while participants may not be familiar with the term ‘comparative effectiveness study’, the idea that the study compares two or more evidence-based strategies – in this case medications that had already been shown to be beneficial when compared with placebo – is likely to be viewed as positive and is worth taking the time to emphasize.

Both consenters and refusers indicated a belief that research is important for medical progress; however, these groups differed in their assessment of perceived risks, burdens and benefits of participation. Our results suggest that initial receptiveness to research participation is associated with prior experiences and perceptions of research-related risk. The least initially receptive included those who were very averse to risk, concerned about exploitation and lacking prior direct experience with research. On the other end of the spectrum, some were initially very receptive, overtly altruistic, and tended to see participation as an opportunity for personal fulfillment and improved health.

Even among individuals with moderate initial receptiveness, several factors mitigated initial willingness to participate (Figure 1). Prior exposure or participation in research was associated with increased likelihood of participating in GRADE. Previous studies have also found a more positive attitude toward research among those with prior exposure or participation [21–23]. Another important influence was the interaction with the study team. When these interactions were perceived as transparent, compassionate and professional, and communication between the potential participant and the study team was good, trust was markedly enhanced. The importance of trust in study staff has been emphasized in several previous reports [24–28]. Our findings suggest specific behaviors associated with higher trustworthiness, including providing personalized care, demonstrating respect, and nonjudgmental approaches. In some cases, endorsement by family members and respected authorities, especially PCPs, increased the likelihood of participation. Negative feedback from PCPs almost always resulted in a loss of interest in participation with GRADE. In light of these findings, research staff training in communication skills is essential. Similarly, investigators should consider developing standardized means for maintaining open communication and active involvement of PCPs during recruitment.

Not surprisingly, refusers typically described lower levels of trust in research, researchers and institutions. Knowledge of, and concern about historical abuses, was noted by several and is a widely recognized reason for mistrust related to research, especially among minority groups [29,30]. Some participants expressed not only mistrust about research but a general distrust in the government and government-funded activities. Such mistrust of the government has been noted in other studies [30–32]. For example, a study that explored the beliefs of African–Americans with regards to HIV, showed that nearly a third held the view that HIV was developed by the government to exterminate the African–American population [31]. Concerns about being ‘experimented on’ and ‘used as a guinea pig’ were also expressed; for many this related to a belief that participation in the study would mostly benefit the investigators and could lead to unknown long-term consequences or harm to the individual. While historical mistrust may be difficult to overcome, it is possible that increased emphasis on specific features of CER, particularly the use of vetted, evidence based-treatments, could help mitigate some of those fears.

A few very receptive individuals still became refusers. In these cases, despite moderate or high levels of trust, the perceived burden of participation outweighed the perceived benefits. Potential study participants expressed fears of being overmedicated, citing potential side effects and ‘dependence’ on drugs as their greatest worry. Many were particularly concerned about pain associated with injections, or specifically the use of insulin. Previous research indicates that many patients associate insulin use with more advanced diabetes and adverse outcomes [33–35]. Other factors included concern about the time burden, physical demands or transportation.

Study limitations

The sample was intended to include geographic and demographic variation, and included refusers as well as consenters. Due to budget and time constraints, it included potential and actual participants from only 5 of the 45 GRADE clinical sites. Differences in staff or approach at the specific GRADE sites might influence the participants’ experiences. It is possible that those who agreed to participate are not fully representative. In particular, it is likely that refusers who agreed to be interviewed are different than those who did not agree to be interviewed. The interviews were conducted by telephone, thus the interviewer could not incorporate visual cues. Our results are specific to the US context and may not be applicable to other racial and ethnic minorities. Nonetheless, we believe that the data obtained were rich and provided new insights on the acceptability of CER among potential study participants.

Conclusion

Potential participants in CER studies have varying levels of receptiveness to research as a result of prior experiences and individual traits. Understanding of research varies, but among those with less knowledge or understanding of research, we found that relationships were key. Personalized and compassionate interactions with the study team can play a critical role in establishing trust even in somewhat reticent individuals. Addressing an individual's past experience with research could provide opportunities to draw upon positive experiences or further explore negative experiences. Study teams should focus efforts on engaging potential influential mediators such as PCPs and family.

Finally, while most potential study participants may not be familiar with research terminology such as ‘comparative effectiveness research’, our results suggest that they may view research designs that compare approved medications more favorably based on lower perceived risk. These findings may also be applicable to other types of trials that are testing the effectiveness of efficacious interventions, as well as pragmatic trials conducted in real-world settings that involve recruitment at the individual level. More education needs to be provided about the benefits of CER and more research is needed to develop strategies that directly address the public’s perception of research and historical issues such as Tuskegee.

Summary points.

This study examined the perspectives on research of individuals who accepted or declined an invitation to participate in the GRADE research study.

Telephone interviews were conducted to explore how participants viewed research in general and the GRADE comparative effectiveness study in particular.

Participants were unaware of how comparative effectiveness research differed from traditional clinical trials but perceived the US FDA-approved drugs as safer once the concept of comparative effectiveness research was explained. Most participants expressed that they would be more likely to participate in this type of research study.

Receptiveness to research was associated with prior experience with research and perceptions of research-related risk.

Initial receptiveness could be modified. Personalized and compassionate interactions with the study team can play a critical role in establishing trust even in somewhat reticent individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank ME Larkin (Massachusetts General Hospital), A Loveland (Medstar Health Research Institute), L Knosp (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics) and AA Agne (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for their help in referring eligible participants for this research project. For full details on the group authorship of this study, please see: Supplementary data.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

To view the supplementary data that accompany this paper please visit the journal website at: www.www.futuremedicine.com/doi/suppl/10.2217/cer-2019-0010

Author contributions

S Behringer-Massera contributed in identification of eligible study participants, recruitment, consenting, telephone interviews, analysis and writing. T Browne and G George contributed in analysis. S Duran contributed in Spanish telephone interviews. A Cherrington contributed in design, analysis and review of manuscript. MD McKee contributed in study design, analysis, review of manuscript, general overview and mentoring. The GRADE research study group carried out all activities of the parent study including recruitment and specifically contributed in identification and referral of eligible study participants for this qualitative study.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research project was funded by the Empire Clinical Researcher and Investigator Program (ECRIP) of New York State. Incentives were supported by internal funds of Montefiore Medical Center. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in this research project.

Data sharing statement

The authors certify that this manuscript reports original clinical trial data. Deidentified, individual data that underlie the results reported in this article (including the interviews and interview guide), will be available indefinitely via this manuscript for anyone who wants access to them.

References

- 1.Paramasivan S, Huddart R, Hall E, Lewis R, Birtle A, Donovan JL. Key issues in recruitment to randomised controlled trials with very different interventions: a qualitative investigation of recruitment to the SPARE trial (CRUK/07/011). Trials 12(1), 78 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paskett ED, Reeves KW, McLaughlin JM. et al. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: the centers for population health and health disparities experience. Contemp. Clin. Trials 29(6), 847–861 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durant RW, Wenzel JA, Scarinci IC. et al. Perspectives on barriers and facilitators to minority recruitment for clinical trials among cancer center leaders, investigators, research staff, and referring clinicians: enhancing minority participation in clinical trials (EMPaCT). Cancer 120(Suppl. 7), 1097–1105 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ME, Siminoff LA, Pickelsimer E. et al. Unequal burden of disease, unequal participation in clinical trials: solutions from African American and Latino community members. Health Soc. Work 38(1), 29–38 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am. J. Public Health 104(2), e16–e31 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 14(9), 537–546 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coakley M, Fadiran EO, Parrish LJ, Griffith RA, Weiss E, Carter C. Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials: successful strategies for engaging women and minorities in clinical trials. J. Womens Health 2002 21(7), 713–716 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 92(12), 563–572 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu. Rev. Public Health 27, 1–28 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wisdom K, Neighbors K, Williams VH, Havstad SL, Tilley BC. Recruitment of African Americans with Type 2 diabetes to a randomized controlled trial using three sources. Ethn. Health 7(4), 267–278 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoel AW, Kayssi A, Brahmanandam S, Belkin M, Conte MS, Nguyen LL. Under-representation of women and ethnic minorities in vascular surgery randomized controlled trials. J. Vasc. Surg. 50(2), 349–354 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cottler LB, McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. et al. Community needs, concerns, and perceptions about health research: findings from the Clinical and Translational Science Award Sentinel Network. Am. J. Public Health 103(9), 1685–1692 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedly J, Bauer Z, Comstock B. et al. Challenges conducting comparative effectiveness research: the Clinical and Health Outcomes Initiative in Comparative Effectiveness (CHOICE) experience. Comp. Eff. Res. 2014(4), 1–12 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Kahn SE. et al. Rationale and design of the glycemia reduction approaches in diabetes: a comparative effectiveness study (GRADE). Diabetes Care 36(8), 2254–2261 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tricoci P. Scientific evidence underlying the ACC/AHA Clinical Practice Guidelines. JAMA 301(8), 831 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC. 2016, Dedoose version 7.5.9. www.dedoose.com

- 17.Eaves YD. A synthesis technique for grounded theory data analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 35(5), 654–663 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mfutso-Bengo J, Masiye F, Molyneux M, Ndebele P, Chilungo A. Why do people refuse to take part in biomedical research studies? Evidence from a resource-poor area. Malawi Med. J. 20(2), 57–63 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wade T, Tiggemann M, Martin NG, Heath AC. Characteristics of interview refusers: women who decline to participate in interviews relating to eating. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 22(1), 95–99 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Underhill K, Morrow KM, Operario D, Mayer KH. Could FDA approval of pre-exposure prophylaxis make a difference? A qualitative study of PrEP acceptability and FDA perceptions among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 18(2), 241–249 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baquet CR, Henderson K, Commiskey P, Morrow JN. Clinical trials: the art of enrollment. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 24(4), 262–269 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerath SM, Klein G, Kern M. et al. Beliefs and attitudes towards participating in genetic research – a population based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 13(1), (2013). http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-13-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gayet-Ageron A, Rudaz S, Perneger T. Biobank attributes associated with higher patient participation: a randomized study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25(1), 31–36 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skaff MM, Chesla CA, de los Santos Mycue V, Fisher L. Lessons in cultural competence: adapting research methodology for Latino participants. J. Community Psychol. 30(3), 305–323 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Buzaitis A. et al. The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Trial (ENRICHD): strategies and techniques for enhancing retention of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depression or social isolation. J. Cardpulm. Rehabil. 23(4), 269–280 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staffileno BA, Coke LA. Recruiting and retaining young, sedentary, hypertension-prone African American women in a physical activity intervention study. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 21(3), 208–216 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tilley BC, Mainous AG, Smith DW. et al. Design of a cluster-randomized minority recruitment trial: RECRUIT. Clin. Trials 14(3), 286–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mainous AG. Development of a measure to assess patient trust in medical researchers. Ann. Fam. Med. 4(3), 247–252 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandon DT, Isaac LA, LaVeist TA. The legacy of Tuskegee and trust in medical care: is Tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? J. Natl Med. Assoc. 97(7), 951–956 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 21(3), 879–897 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klonoff EA, Landrine H. Do blacks believe that HIV/AIDS is a government conspiracy against them? Prev. Med. 28(5), 451–457 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ejiogu N, Norbeck JH, Mason MA, Cromwell BC, Zonderman AB, Evans MK. Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: lessons from the healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span study. Gerontologist 51(Suppl. 1), S33–S45 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allen NA, Zagarins SE, Feinberg RG, Welch G. Treating psychological insulin resistance in Type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 7, 1–6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larkin ME, Capasso VA, Chen C-L. et al. Measuring psychological insulin resistance. Diabetes Educ. 34(3), 511–517 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor CG, Taylor G, Atherley A, Hambleton I, Unwin N, Adams OP. The Barbados Insulin Matters (BIM) study: barriers to insulin therapy among a population-based sample of people with Type 2 diabetes in the Caribbean island of Barbados. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 8, 49–53 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.