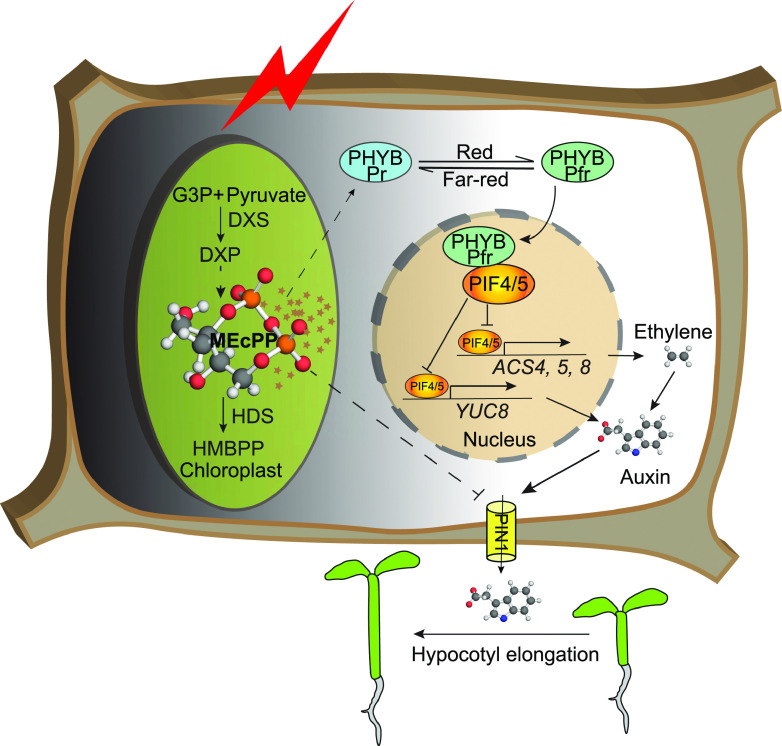

The plastidial retrograde metabolite MEcPP orchestrates coordination of the light and hormonal signaling cascade by inducing phytochrome B abundance and modulating auxin and ethylene levels.

Abstract

Exquisitely regulated plastid-to-nucleus communication by retrograde signaling pathways is essential for fine-tuning of responses to the prevailing environmental conditions. The plastidial retrograde signaling metabolite methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP) has emerged as a stress signal transduced into a diverse ensemble of response outputs. Here, we demonstrate enhanced phytochrome B protein abundance in red light-grown MEcPP-accumulating ceh1 mutant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants relative to wild-type seedlings. We further establish MEcPP-mediated coordination of phytochrome B with auxin and ethylene signaling pathways and uncover differential hypocotyl growth of red light-grown seedlings in response to these phytohormones. Genetic and pharmacological interference with ethylene and auxin pathways outlines the hierarchy of responses, placing ethylene epistatic to the auxin signaling pathway. Collectively, our findings establish a key role of a plastidial retrograde metabolite in orchestrating the transduction of a repertoire of signaling cascades. This work positions plastids at the zenith of relaying information coordinating external signals and internal regulatory circuitry to secure organismal integrity.

Dynamic alignment of internal and external cues through the activation of corresponding signal transduction pathways is a defining characteristic of organisms essential for fitness and the balancing act of metabolic investment in growth versus adaptive responses. The integrity of these responses is achieved through finely controlled communication circuitry, notably retrograde (organelle-to-nucleus) signaling cascades. Despite the central role of retrograde signaling in the regulation and coordination of numerous adaptive processes, the nature and the operational mode of action of retrograde signals have remained poorly understood.

Through a forward-genetic screen, we identified a bifunctional plastid-produced metabolite, methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP), that serves as a precursor of isoprenoids produced by the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway and functions as a stress-specific retrograde signaling metabolite (Xiao et al., 2012). We further demonstrated that stress-induced MEcPP accumulation leads to growth retardation and the induction of selected nucleus-encoded, stress-response genes (Xiao et al., 2012; Walley et al., 2015; Lemos et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). We specifically established that regulation of growth is in part via MEcPP-mediated modulation of the levels and distribution patterns of auxin (indole-3-acetic acid [IAA]) through dual transcriptional and posttranslational regulatory inputs (Jiang et al., 2018).

Auxin functions as a key hormone regulating a repertoire of plant development processes including hypocotyl growth (Jensen et al., 1998; De Grauwe et al., 2005). The auxin biosynthesis pathway that converts Trp to IAA in plants is established to be through the conversion of Trp to indole-3-pyruvate by the TAA family of amino transferases and subsequent production of IAA from indole-3-pyruvate by the YUC family, a family of flavin monooxygenases (Zhao, 2012). Subsequently, the establishment of an auxin gradient is achieved by transporters such as the auxin-efflux carrier PIN-FORMED1 (PIN1; Gälweiler et al., 1998; Geldner et al., 2001). Interestingly, IAA biosynthesis, transport, and signaling during light-mediated hypocotyl growth are in turn regulated by ethylene (Liang et al., 2012), and conversely, ethylene is regulated by auxin (Vandenbussche et al., 2003; Růzicka et al., 2007; Stepanova et al., 2007; Swarup et al., 2007; Negi et al., 2010). As such, auxin-ethylene cross talk inserts an additional layer of complexity to the already intricate and multifaceted growth regulatory mechanisms.

Ethylene in plants is derived from the conversion of S-adenosyl-l-Met to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) by ACC synthase (ACS; Yang and Hoffman, 1984), followed by the conversion of ACC to ethylene catalyzed by ACC oxidase (Wang et al., 2002). Ethylene stimulates hypocotyl growth in the light but inhibits it in the dark (Smalle et al., 1997; Jensen et al., 1998; Vandenbussche et al., 2012).

Light signaling is a common environmental stimulus controlling developmental processes through hormonal modulation, such as the regulation of auxin biosynthesis and signaling genes by phytochrome B (phyB; Morelli and Ruberti, 2002; Tanaka et al., 2002; Tian et al., 2002; Nozue et al., 2011; Hornitschek et al., 2012; de Wit et al., 2014; Leivar and Monte, 2014). PhyB is the main photoreceptor mediating red light photomorphogenesis; phyB is activated by red light and imported into the nucleus, where it forms phyB-containing nuclear bodies (Nagy and Schäfer, 2002; Quail, 2002). The formation of phyB-containing nuclear bodies depends on binding to and sequestration of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, PHYTOCHROME INTERACTING FACTOR1 (PIF1), PIF3, PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7 (Rausenberger et al., 2010; Leivar and Quail, 2011). The prominent role of phyB in auxin regulation is best displayed by the simulation of shade-avoidance responses through exogenous application of auxin or via genetic manipulation of auxin (Tanaka et al., 2002; Hornitschek et al., 2012). In addition, PIFs, specifically PIF4, PIF5, and PIF7, play a major role in regulating auxin by targeting promoter elements of multiple auxin biosynthetic and signal transduction genes (Franklin et al., 2011; Nozue et al., 2011; Leivar et al., 2012; Sellaro et al., 2012; Leivar and Monte, 2014). Moreover, the ethylene-promoted hypocotyl elongation in light is regulated by the PIF3-dependent, growth-promoting pathway activated transcriptionally by EIN3, whereas under dark conditions, ethylene inhibits growth by destabilizing the ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 (Zhong et al., 2012).

Here, we identify MEcPP as an Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) retrograde signaling metabolite that coordinates internal and external cues, and we further delineate light and hormonal signaling cascades that elicit adaptive responses to ultimately drive growth-regulating processes tailored to the prevailing environment.

RESULTS

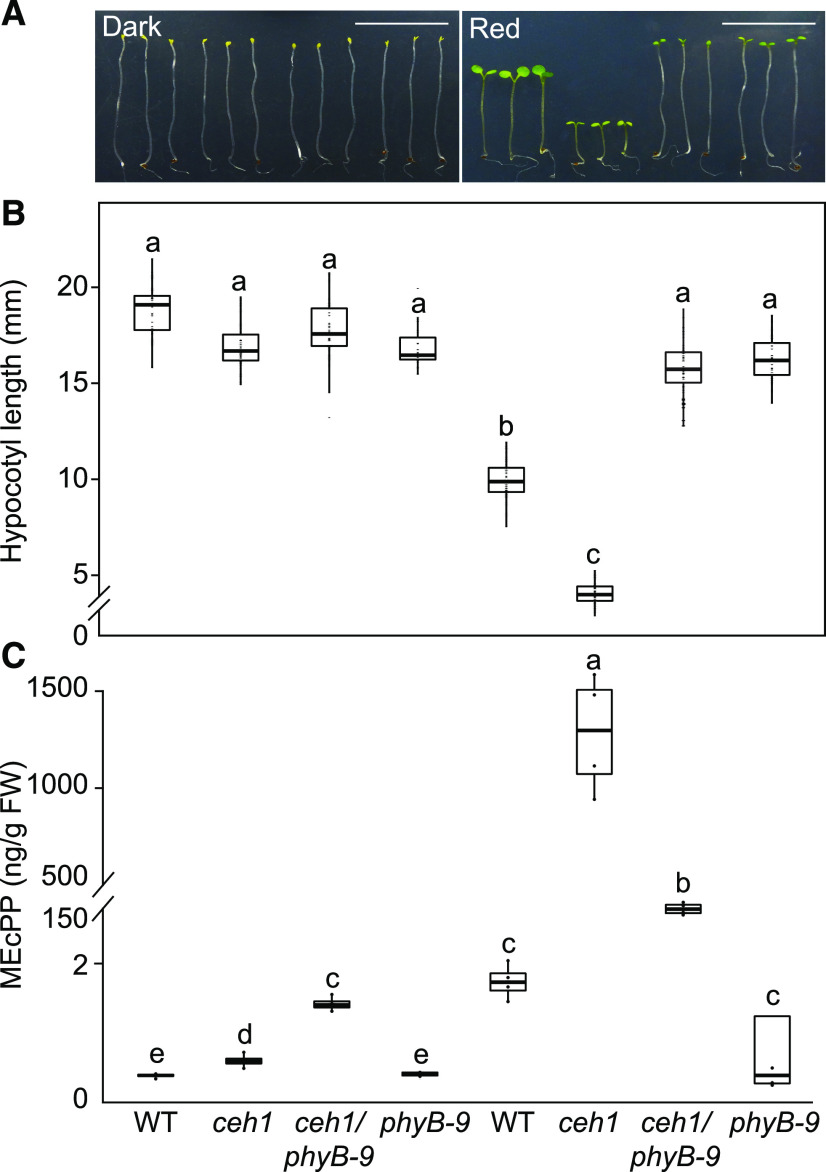

Elevated phyB Abundance Suppresses Hypocotyl Growth in ceh1

Given the stunted hypocotyl phenotype of the high MEcPP-accumulating mutant ceh1, we explored the nature of the photoreceptors involved by examining the hypocotyl length of seedlings grown in the dark and under various monochromatic light conditions. The analyses showed comparable hypocotyl lengths of dark-grown ceh1 and control (wild-type) seedlings (Fig. 1A). However, under continuous red light (Rc; 15 μE m−2 s−1), ceh1 seedlings displayed notably shorter hypocotyls than those of wild-type plants (Fig. 1A). These data led us to question the role of phyB, the prominent red light photoreceptor, in regulating ceh1 hypocotyl growth. To answer this question, we generated a ceh1/phyB-9 double mutant line and subsequently compared seedling hypocotyl length with wild-type, ceh1, and phyB-9 seedlings grown under continuous dark and Rc conditions (Fig. 1, A and B). The data clearly demonstrated the phyB-dependent suppression of hypocotyl growth in ceh1 under Rc, as evidenced by the recovery of ceh1 retarded hypocotyl growth in ceh1/phyB-9 to lengths comparable to those of phyB-9 seedlings.

Figure 1.

ceh1 hypocotyl growth in red light is phyB dependent. A, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type, ceh1, ceh1/phyB-9, and phyB-9 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Bars = 1 cm. B, Quantification of hypocotyl lengths from the genotypes shown in A. C, MEcPP levels of samples from A. The breaks indicates changes of scale on the y axes. Statistical analyses were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) method (n ≥ 45), and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight; WT, wild type.

Hypocotyl growth of the aforementioned four genotypes was also examined under continuous blue (Bc) and far-red (FRc) light conditions. The reduced hypocotyl growth of the ceh1 mutant grown under Bc, albeit not as severe as that grown under Rc, further implicates blue light-receptor cytochromes (Yu et al., 2010) in regulating the growth of these seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Additionally, ceh1 and ceh1/phyB-9 seedlings grown under Bc exhibited equally shortened hypocotyls, and under FRc, hypocotyl growth was almost similarly retarded in all genotypes (Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B). Collectively, these results support the involvement of cryptochromes as well as phyB in ceh1 hypocotyl growth, albeit to different degrees. However, the more drastic effect of phyB in regulating hypocotyl growth of Rc-grown, high MEcPP-accumulating seedlings, in conjunction with the supporting evidence from earlier data using white light-grown ceh1 seedlings (Jiang et al., 2019), led us to primarily focus on the role of phyB.

Next, we measured MEcPP levels in the four genotypes grown in the dark and in various monochromatic wavelengths to examine a potential correlation between growth phenotypes and altered levels of the retrograde signaling metabolite (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Fig. S1C). The analyses showed almost undetectable MEcPP levels in dark-grown plants of all the genotypes and low levels of the metabolite in Rc-grown wild-type and phyB-9 seedlings. By contrast, ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc accumulated high MEcPP levels, a phenotype that was partially (∼10-fold) suppressed in ceh1/phyB-9 seedlings. This reduction was not unexpected, since phyB-controlled PIF regulates the expression of DXS, the first MEP pathway gene encoding the flux determinant enzyme (Chenge-Espinosa et al., 2018). It is noteworthy that despite this significant reduction, the MEcPP content of ceh1/phyB-9 seedlings remained ∼100-fold above those of wild-type or phyB-9 plants grown simultaneously and under the same conditions. This reduction of MEcPP in ceh1/phyB-9 also occurred in seedlings grown in Bc (Supplemental Fig. S1C), likely because of the direct interaction between PIFs and blue light-receptor cryptochromes (Pedmale et al., 2016). However, in spite of the reduced MEcPP levels in Rc- or Bc-grown ceh1/phyB-9 seedlings, the hypocotyl growth recovery is exclusive to mutant seedlings grown in Rc (Fig. 1; Supplemental Fig. S1, A–C), leading to the conclusion that there is also a blue light-dependent pathway that regulates ceh1 hypocotyl growth in Bc. Moreover, hypocotyls of all genotypes, regardless of their MEcPP levels, remained stunted in FRc, a light condition known to inactivate phyB. Collectively, these results further verify the function of phyB in altering the observed growth phenotype of ceh1 mutant seedlings.

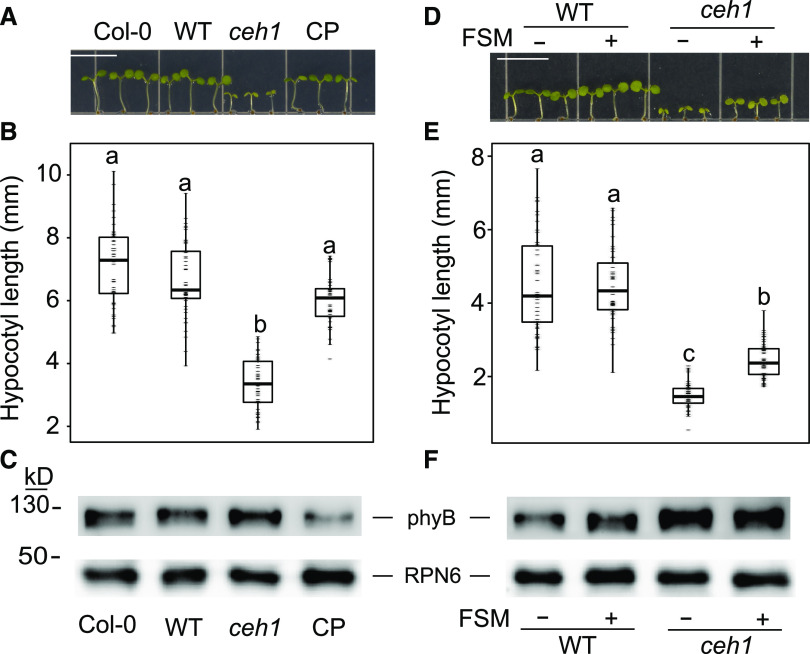

To examine the correlation between accumulation of MEcPP and alteration of growth in response to red light treatment, we further examined the hypocotyl length of Columbia-0 (Col-0), Col-0 transformed with the HPL:LUC construct (wild-type), ceh1, and complemented ceh1 (CP) seedlings (Fig. 2, A and B). In contrast to the stunted hypocotyl growth of ceh1, these data clearly showed recovery of hypocotyl growth in CP to lengths comparable to Col-0 and wild-type seedlings (Fig. 2, A and B).

Figure 2.

MEcPP induction of phyB results in stunted ceh1 hypocotyl growth. A, Representative image of 7-d-old Col-0, wild-type (WT), ceh1, and CP seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Bar = 1 cm. B and E, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings from A and D, respectively. Data are presented from 45 seedlings. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). C and F, Immunoblots of phyB protein abundance, using RPN6 antibody as a loading control. D, Representative image of 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of FSM (20 μm). Bar = 1 cm.

Next, we questioned whether phyB transcript and/or protein levels are altered in ceh1 mutants grown in Rc. The expression data analyses revealed similar PHYB transcript levels in ceh1 and wild-type seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S1D). To determine the hyB protein levels, we performed immunoblot analyses using proteins isolated from the aforementioned genotypes (Fig. 2C). The data showed higher phyB levels in ceh1 versus other genotypes specifically as compared with CP, supporting the conclusion that MEcPP mediates enhanced abundance of phyB.

To further examine the potential role of MEcPP in ceh1 in reducing growth and altering phyB levels, we employed a pharmacological approach using fosmidomycin (FSM), a MEP pathway inhibitor (Fig. 2, D–F). This inhibitor interferes with and highly reduces the flux through the pathway and abolishes MEcPP-mediated actions such as the formation of otherwise stress-induced subcellular structures known as endoplasmic reticulum bodies or furthering the reduced auxin levels in ceh1 mutant plants (Gonzalez-Cabanelas et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2018). We examined the hypocotyl growth of red light-grown 7-d-old seedlings that were treated with FSM for 3 d. These data showed enhanced hypocotyl growth of FSM-treated ceh1 compared with nontreated seedlings (Fig. 2, D and E). It is of note that the length of FSM-treated ceh1 hypocotyls did not recover to that of the wild-type seedlings, suggesting an inefficiency of FSM treatment and/or the presence of other regulatory factors. In addition, immunoblot analysis showed a very slight reduction in phyB abundance in FSM-treated ceh1 compared with nontreated seedlings (Fig. 2F). There may be two reasons for not detecting an overall stronger response to FSM treatment. One is the very high MEcPP levels in the ceh1 mutant, and the other is the degree of FSM penetration. However, the clearly higher phyB levels in the ceh1 mutant compared with CP, wild-type, and Col-0 lines support the notion of MEcPP-mediated increase of phyB abundance, verifying the earlier report using white light-grown seedlings (Jiang et al., 2019).

In addition to MEcPP, the ceh1 mutant accumulates substantial amounts of the defense hormone salicylic acid (SA; Xiao et al., 2012; Bjornson et al., 2017). The reported involvement of phyB in SA accumulation and signaling (Chai et al., 2015; Nozue et al., 2018) prompted us to examine the potential role of this defense hormone in regulating ceh1 hypocotyl growth. For these experiments, we employed the previously generated SA-deficient double mutant line ceh1/eds16 (Xiao et al., 2012). All four genotypes (the wild type, ceh1, ceh1/eds16, and eds16) displayed similar hypocotyl length when grown in the dark, whereas in Rc, both ceh1 and ceh1/eds16 seedlings displayed equally reduced hypocotyl lengths as compared with their respective control backgrounds (Supplemental Fig. S1G). These results illustrate the SA-independent regulation of ceh1 hypocotyl growth in Rc.

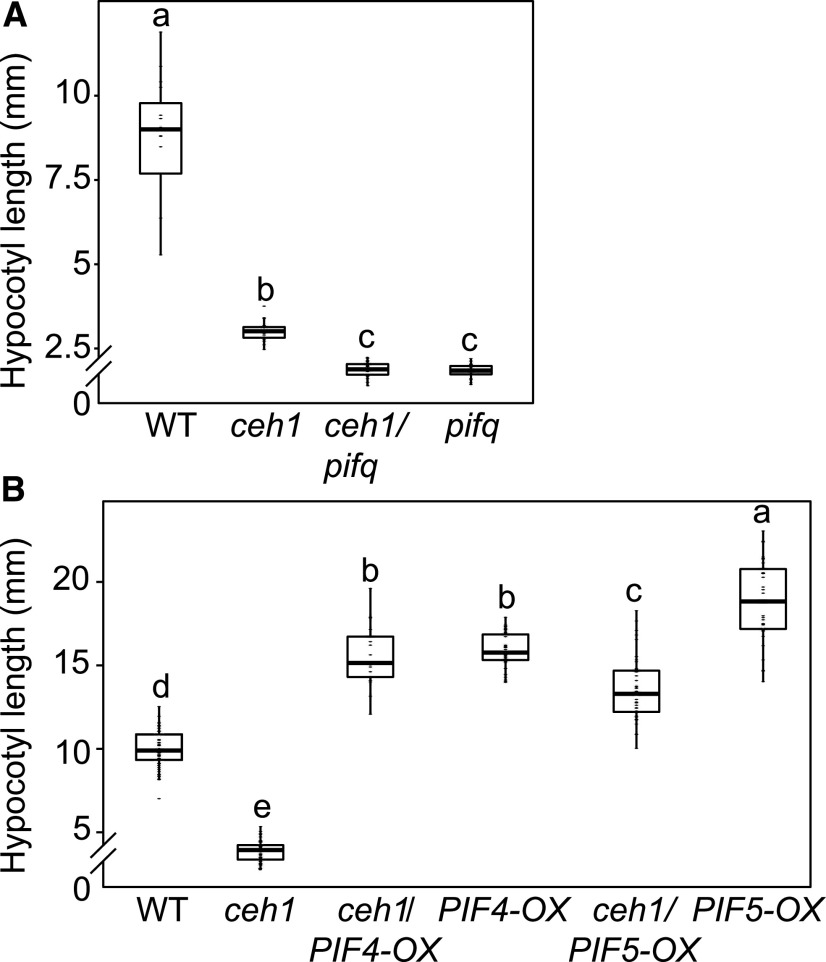

Given the well-established role of PIFs in the transduction of phyB signals, we examined PIF expression levels and found significantly reduced PIF4 and PIF5 transcripts in Rc-grown ceh1 compared with wild-type seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S2). These data led us to genetically investigate the potential role of PIFs in regulating the hypocotyl length of Rc-grown ceh1 seedlings. For these experiments, we quantified hypocotyl growth of pifq (pif1, pif3, pif4, and pif5) alone and in lines introgressed into the ceh1 mutant background. The results revealed similarly dwarf hypocotyls in ceh1/pifq and pifq backgrounds, which were slightly but significantly shorter than that of ceh1 seedlings (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, equally reduced hypocotyl growth in ceh1/pifq and pifq suggest that PIFs are the predominant growth regulators in ceh1 under the experimental conditions employed. The role of PIFs in determining hypocotyl growth was further tested by examining ceh1 seedlings overexpressing PIF4 and PIF5 grown in Rc (Fig. 3B). These data showed the expected enhanced hypocotyl growth of PIF overexpressors compared with wild-type seedlings and the recovery of the retarded growth observed in ceh1 in ceh1/PIF4 and PIF5 overexpression lines.

Figure 3.

Overexpression of PIF4 and PIF5 recovers the stunted hypocotyl growth of ceh1. A, Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of 7-d-old wild-type (WT), ceh1, ceh1/pifq, and pifq grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). B, Quantification of hypocotyl lengths from 7-d-old wild-type, ceh1, ceh1/PIF4-OX, PIF4-OX, ceh1/PIF5-OX, and PIF5-OX grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). n ≥ 20 for the pif mutant background and n ≥ 30 for the experiments containing PIF-OX seedlings. The breaks indicate changes of scale on the y axes. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method, and different letters indicate significant differences.

Collectively, these data illustrate the growth regulatory function of PIFs and identify MEcPP-mediated transcriptional regulation of PIF4 and PIF5 as an integral regulatory circuit controlling ceh1 hypocotyl growth.

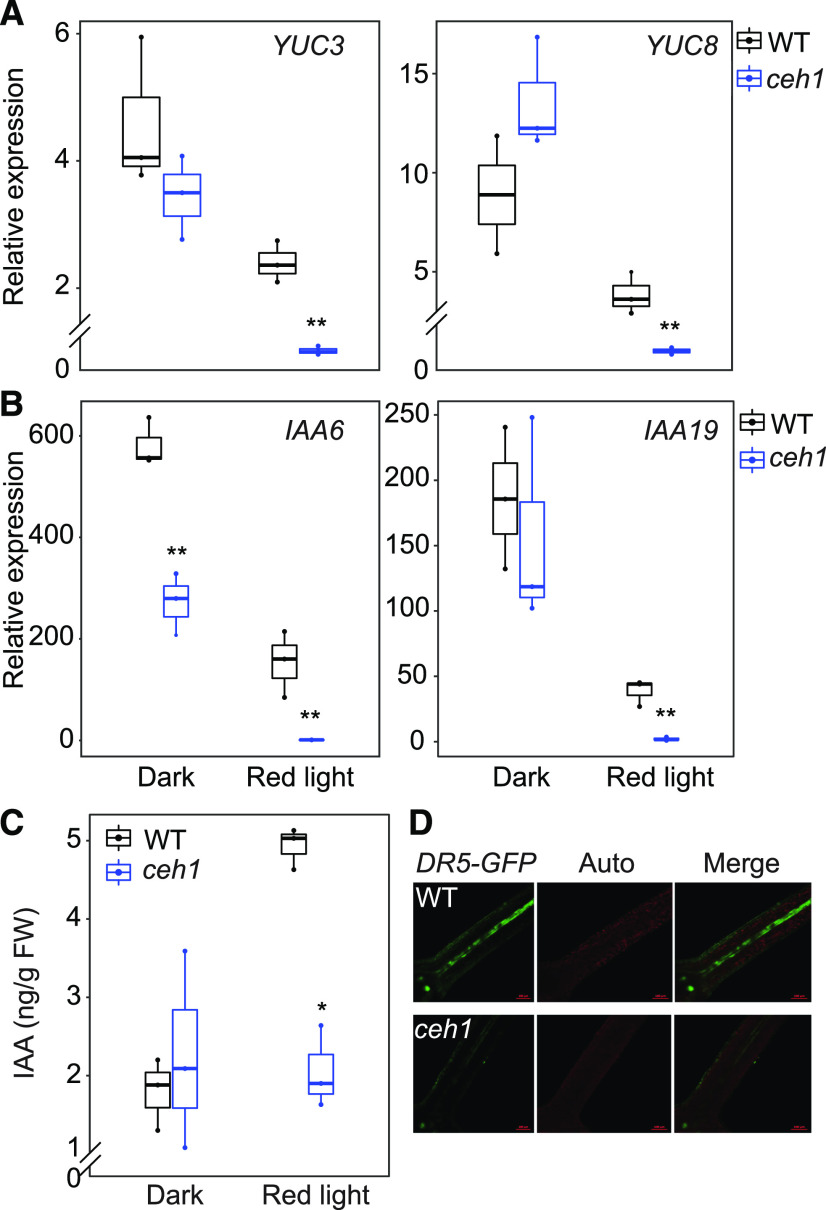

Reduced Expression of Auxin Biosynthesis and Response Genes in ceh1

To identify the downstream components of the MEcPP-mediated phyB signaling cascade, we performed RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) profiling of wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and in Rc. A multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot revealed significant overlap between expression profiles of wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark, in contrast to their distinct expression profiles when grown in Rc (Supplemental Fig. S3). Gene Ontology (GO) term analyses identified overrepresentations of auxin signaling and response genes among the significantly (2-fold or greater) altered transcripts (Supplemental Fig. S4). Confirmation of the data through reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) identified auxin biosynthesis (YUC3 and YUC8) and response (IAA6 and IAA19) genes as the most significantly differentially expressed genes under Rc conditions (Fig. 4, A and B). We further quantified the IAA content in plants and found similar auxin levels in dark-grown plants of all genotypes, in contrast to significantly reduced auxin levels (50%) in Rc-grown ceh1 versus wild-type plants (Fig. 4C). We validated this finding by testing Rc-grown wild-type and ceh1 lines expressing the auxin signaling reporter DR5-GFP (Jiang et al., 2018). The reduced GFP signal in ceh1 was on par with lower IAA levels in mutant compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4.

Auxin is reduced in ceh1. A and B, Expression levels of YUC3 and YUC8 (A) and IAA6 and IAA19 (B) in wild-type (WT) and ceh1 seedlings. RNAs were extracted from 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Transcript levels of the target genes were normalized to the levels of At4g26410 (M3E9). Data are presented from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Statistical analyses were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test with significance indicated by asterisks (**P < 0.01). C, IAA levels in 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Data are presented from three biological replicates. Statistical analyses were carried out by two-tailed Student’s t test with significance indicated by the asterisk (*P < 0.05). FW, Fresh weight. The breaks indicate changes of scale on the y axes in A and C. D, Representative images of DR5-GFP signal intensity in 7-d-old hypocotyls of Rc-grown (15 μE m−2 s−1) wild-type and ceh1 seedlings. DR5-GFP (green), chloroplast fluorescence (red), and merged images are shown.

Next, we examined possible modulation of other phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA) and jasmonic acid (JA) in response to high MEcPP levels in ceh1 seedlings (Supplemental Fig. S5). Similar ABA and JA levels found in wild-type and ceh1 plants grown in the dark and in Rc strongly support the specificity of MEcPP-mediated regulation of auxin.

Enhanced Tolerance of ceh1 to Auxin and Auxinole

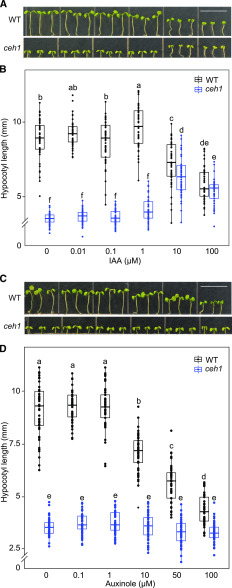

Reduced IAA levels in ceh1 led us to examine whether external application of this hormone could rescue the retarded hypocotyl growth in ceh1 seedlings. The analyses showed longer hypocotyls in ceh1 seedlings treated with IAA at concentrations (10 and 100 μm) that inhibited growth in wild-type seedlings (Fig. 5, A and B). Interestingly, ceh1 and wild-type hypocotyls displayed similar lengths when treated with the highest IAA concentration used here (100 μm), albeit through two opposing responses, namely growth suppression in the wild type and induction in ceh1.

Figure 5.

Enhanced tolerance of ceh1 to auxin and auxinole. A and C, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type (WT) and ceh1 seedlings in the absence and presence of IAA and auxinole grown under Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Bars = 1 cm. B and D, Quantification of hypocotyl lengths of seedlings from A and C, respectively. Zero indicates the absence of IAA. Data are presented from 45 seedlings. The breaks indicate changes of scale on the y axes. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

This finding led to the hypothesis that the enhanced tolerance of ceh1 to auxin treatment is not solely the result of reduced auxin levels in the mutant but also a consequence of modified auxin signaling in the mutant. To address this possibility, we treated wild-type and ceh1 seedlings with auxinole, an auxin signaling inhibitor that functions as an auxin antagonist for TIR1/AFB receptors (Hayashi et al., 2008, 2012). The analyses showed clear dose-dependent suppression of hypocotyl growth of wild-type seedlings in response to auxinole treatment, in contrast to the unresponsiveness of ceh1 seedlings at all concentrations examined (Fig. 5, C and D). Collectively, these data indicated enhanced tolerance of ceh1 to otherwise inhibitory concentrations of auxin and auxinole, likely stemming from reduced auxin levels and compromised signaling in the mutant line.

Altered Auxin Transport in ceh1

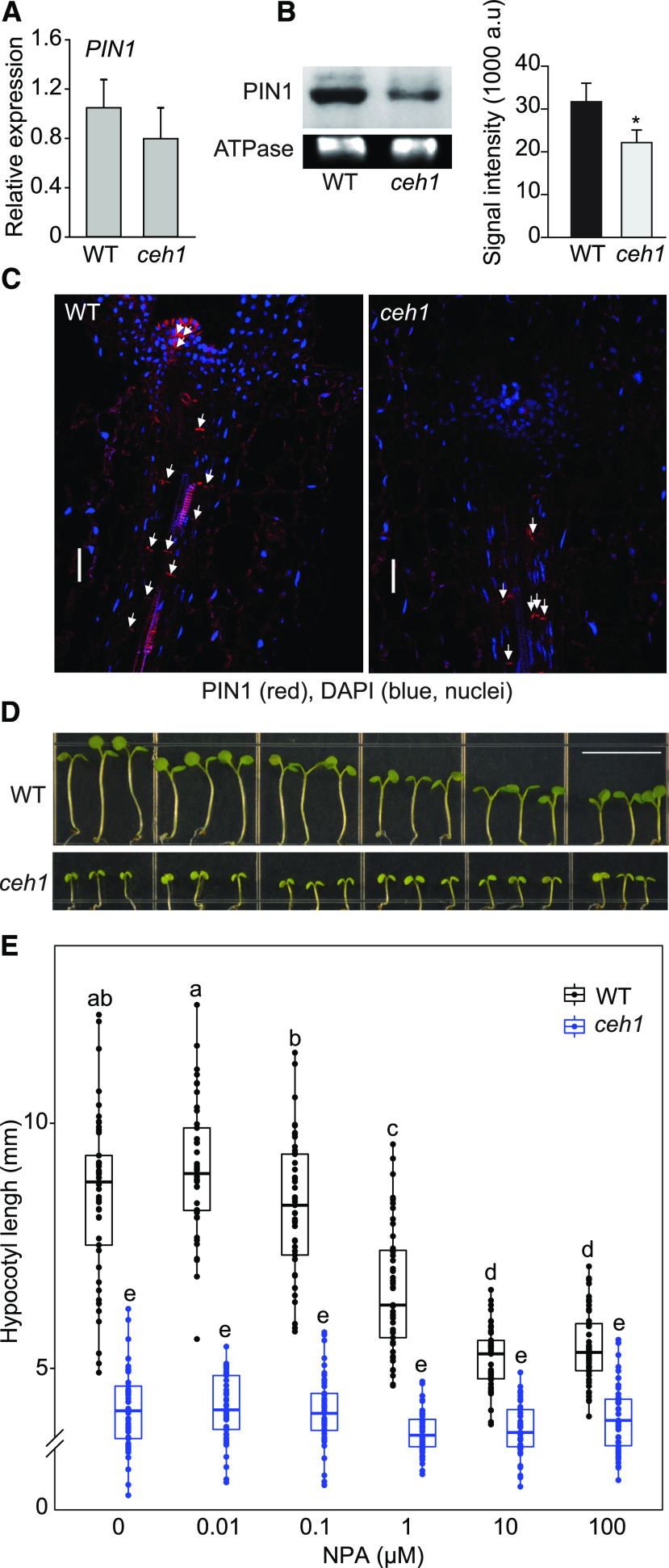

We have previously established that the MEcPP-mediated modulation of levels and distribution patterns of auxin (IAA) is via dual transcriptional and posttranslational regulatory inputs (Jiang et al., 2018). We specifically demonstrated reduced transcript and protein levels of the auxin efflux transporter PIN1 in ceh1 seedlings grown in white light. Here, we extended those analyses to Rc-grown seedlings, initially by expression analyses of PIN1 in the wild type and ceh1. The analyses showed similar PIN1 transcript levels in ceh1 and wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6A). By contrast, the combined approaches of immunoblot and immunolocalization analyses confirmed a significant reduction in PIN1 protein levels in ceh1 compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 6, B and C). Specifically, immunolocalization clearly showed reduced PIN1 protein abundance in plasma membranes of xylem parenchyma cells (along tracheids), most notably in the meristems of ceh1 compared with wild-type seedlings, albeit with an unchanged polarity (Fig. 6C). These data support the earlier finding establishing the role of MEcPP in modulating PIN1 protein abundance both in Rc- and white light-grown seedlings (Jiang et al., 2018).

Figure 6.

Altered auxin transport in ceh1. A, PIN1 expression levels in 7-d-old wild-type (WT) and ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). The experiment was performed as described for Figure 4A. Data are presented from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. B, Immunoblots of PIN1 and ATPase as the protein loading control, and signal intensity quantification of the PIN1/ATPase protein abundance in 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown under Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) with two biological replicates. The asterisk denotes a significant difference as determined by two-tailed Student’s t test (*P < 0.05). C, Immunolocalization of PIN1 in the hypocotyls of 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown under Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Bars = 20 μm. D, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown under Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) in the absence and presence of NPA. Bar = 1 cm. E, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings from D. 0 indicates the absence of NPA. The break indicates a change of scale on the y axis. Data are presented from 45 seedlings. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method. Data are means ± sd, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

The reduced levels of the major auxin transporter PIN1 led us to examine the impact of varying concentrations of a general auxin polar transport inhibitor, specifically 1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA; Scanlon, 2003), on the hypocotyl growth of wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc (Fig. 6, D and E). As expected, NPA application reduced wild-type hypocotyl growth in a dose-dependent manner, which contrasts with the lack of detectable response in ceh1, thereby confirming compromised auxin transport in the mutant.

Ethylene Regulates Hypocotyl Growth in ceh1

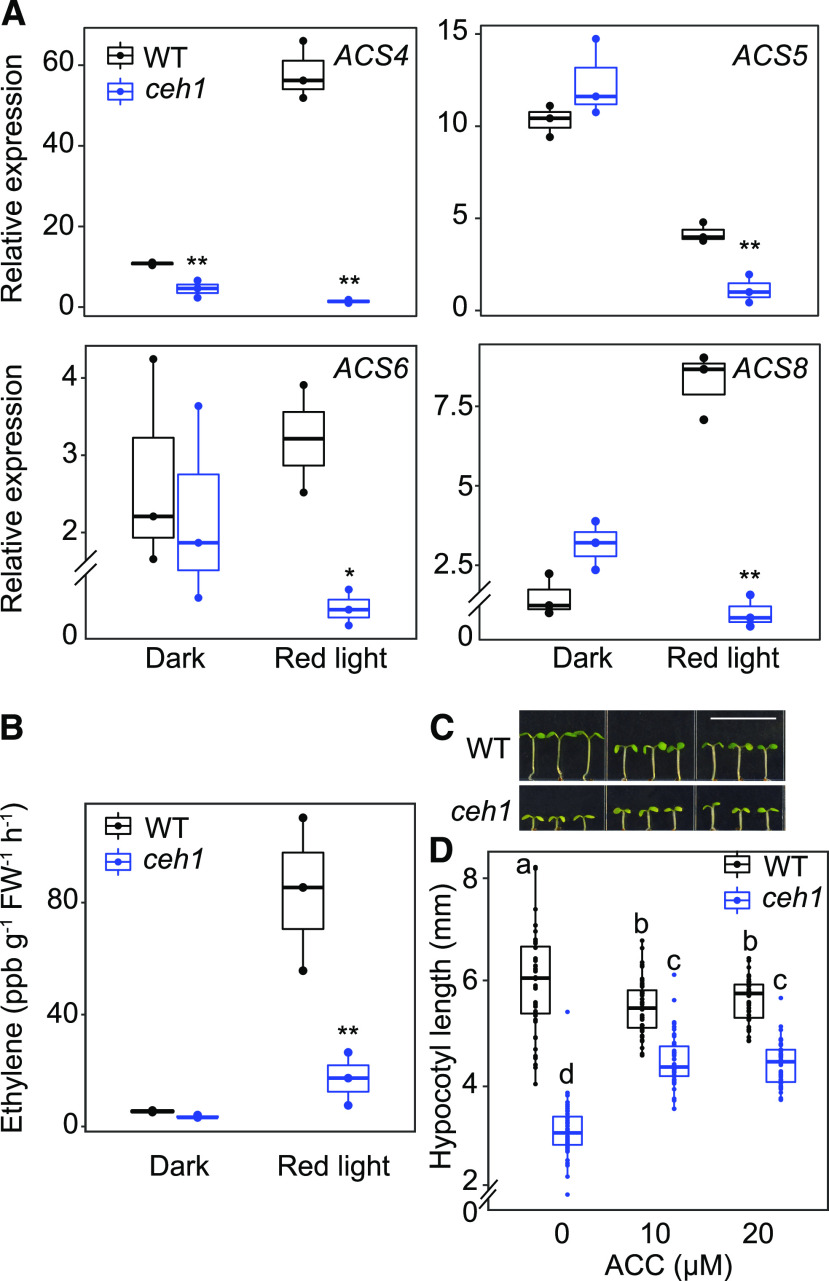

Comparative transcriptomic profiling of wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc revealed reduced levels of ethylene biosynthesis genes, ACSs (Supplemental Table S1), in the mutant. This observation, in conjunction with the established cross talk between ethylene and auxin (Yu et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Das et al., 2016), prompted us to further investigate the potential function of ethylene in regulating ceh1 hypocotyl growth. Initially, we performed RT-qPCR analyses on ethylene biosynthesis genes to validate the original transcriptomic profile data (Supplemental Table S1; Supplemental Fig. S4). The data showed that compared with wild-type seedlings, there is a prominent reduction in the transcript levels of ACS4 in dark- and Rc-grown ceh1 seedlings (≥ 2-fold and ∼60-fold, respectively) as well as a notable (3- to 10-fold depending on the gene) reduced expression of ACS5, ACS6, and ACS8, albeit solely in Rc-grown ceh1 (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Ethylene regulates hypocotyl growth in ceh1. A, Expression levels of ACS4, ACS5, ACS6, and ACS8 in 7-d-old wild-type (WT) and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). The experiment was performed as described for Figure 4A. Data are presented from three biological replicates and three technical replicates. Statistical analyses were determined by two-tailed Student’s t test with significance indicated by asterisks (* P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01). B, Ethylene levels in samples used in A. FW, Fresh weight. C, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the absence and presence of ACC in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1). Bar = 1 cm. D, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings from C. 0 indicates the absence of ACC. Data are presented from 45 seedlings. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). The breaks indicates changes of scale on the y axes in A and D.

Measurements of ethylene in these seedlings confirmed reduced levels (∼80%) of the hormone in Rc-grown ceh1 compared with wild-type seedlings (Fig. 7B). This led us to examine hypocotyl growth of seedlings grown in the presence of varying concentrations of the ethylene precursor ACC (Fig. 7, C and D). The data show the suppression of wild-type hypocotyl growth at all concentrations examined, as opposed to equally enhanced hypocotyl growth in ceh1 at both ACC concentrations (10 and 20 μm), an indication of saturation of the growth response. Altogether, these data support MEcPP-mediated coordination of red light signaling cascades with ethylene levels and ethylene regulation of hypocotyl growth.

Hierarchy of Ethylene and Auxin Signaling Pathways

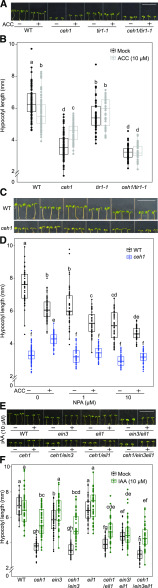

The partial recovery of ceh1 hypocotyl growth by external application of auxin and ethylene, albeit to varying degrees, prompted us to genetically explore their potential interdependency and hierarchy of their respective growth regulatory actions in Rc-grown seedlings. To address this, we applied ACC and IAA independently to mutant lines ceh1, ceh1 introgressed into the auxin receptor mutant tir1-1 (ceh1/tir1-1), and ceh1 introgressed into the single ethylene signaling mutants ein3 and eil1 (ceh1/ein3 and ceh1/eil1) and the double mutant ein3 eil1 (ceh1/ein3 eil1).

Analyses of the hypocotyl lengths of Rc-grown wild-type, ceh1, ceh1/tir1-1, and tir1-1 seedlings in the absence and presence of ACC demonstrated the TIR1-dependent growth-promoting action of ACC in tir1-1 and ceh1/tir1-1 (Fig. 8, A and B). We furthered these studies by applying ACC alone or together with NPA (Fig. 8, C and D). Consistent with the earlier data, ACC treatment promoted ceh1 hypocotyl growth, but less effectively when combined with the auxin polar transport inhibitor NPA (Fig. 8, C and D).

Figure 8.

Ethylene is epistatic to auxin. A, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type (WT), ceh1, ceh1/tir1-1, and tir1-1 seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of ACC. C, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of ACC/NPA alone or in combination. E, Representative images of 7-d-old wild-type, ceh1, ein3, ceh1/ein3, eil1, ceh1/eil1, ein3/eil1, and ceh1/ein3 eil1 seedlings grown in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1) in the absence (−) and presence (+) of IAA. B, D, and F, Quantification of hypocotyl length of seedlings from A, C, and E, respectively. Data are presented from 45 seedlings. The breaks indicates changes of scale on the y axes. Statistical analyses were carried out using Tukey’s HSD method, and different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Bars = 1 cm.

In parallel, we examined the hypocotyl growth of Rc-grown wild-type, ceh1, ein3, ceh1/ein3, eil1, ceh1/eil1, ein3/eil1, and ceh1/ein3 eil1 seedlings in the presence and absence of externally applied IAA (Fig. 8, E and F). Enhanced growth of ceh1 hypocotyls in the presence of IAA irrespective of mutant background (single or double ein3/eil1) reaffirmed the growth-promoting function of auxin even in lines perturbed in ethylene signaling.

This finding establishes the dependency of ethylene function on auxin signaling, delineating the hierarchy of responses and positioning ethylene as epistatic to the auxin signaling pathway.

DISCUSSION

An inherent feature of plant growth and development is the capacity to coordinate and integrate external cues with endogenous regulatory pathways through tightly regulated signaling cascades. Recent studies have identified retrograde signaling as a quintessential mode of cellular communication required for optimal organismal response to prevailing conditions. Here, we provide a coherent picture of how the stress-specific plastidial retrograde signaling metabolite (MEcPP) coordinates light and hormonal signaling circuitries to adjust growth to the most prevalent environmental cue, light conditions.

Our simplified schematic model (Fig. 9) depicts MEcPP as the upstream signal coordinating and modulating drivers of growth, specifically through enhancing phyB protein abundance and the consequential reduction of auxin levels and distribution in conjunction with diminished ethylene content.

Figure 9.

Schematic model depicting MEcPP as the integrator of growth-regulating pathways. Stress induction of MEcPP accumulation reduces the expression of PIF4 and PIF5 and enhances the abundance of phyB protein and the consequential orchestration of ethylene-auxin hierarchy to regulate growth.

The degradation of phyB is established to be through an intermolecular transaction of this photoreceptor with PIF transcription factors (Ni et al., 2013), thereby supporting the prospect of significantly reduced PIF4 and PIF5 transcript levels as the likely cause of enhanced phyB protein abundance in ceh1 seedlings grown in Rc. Furthermore, the reversion of ceh1-stunted hypocotyls in ceh1/phyB-9 confirms the key role of enhanced phyB protein abundance in growth retardation of the mutant, confirming the earlier finding using white light-grown seedlings (Jiang et al., 2019).

The role of phyB in regulating growth is reported to be through repressing auxin-response genes (Devlin et al., 2003; Halliday et al., 2009). The red light-mediated reduction of auxin biosynthesis and signaling together with decreased hormone levels in ceh1 support phyB function in auxin regulation. In addition, reduced levels of PIN1 protein abundance, as evidenced by immunoblot and immunolocalization assays, suggest the regulatory role of phyB in controlling auxin transport via the modulation of PIN1 protein levels. This notion is supported by the ineffectiveness of the auxin transport inhibitor in modulating the hypocotyl growth of Rc-grown ceh1 seedlings.

Similar to auxin, the reduction of ethylene levels, partly due to decreased transcript levels of the respective biosynthesis genes in Rc-grown ceh1, strongly supports the regulatory role of MEcPP-mediated induction of phyB in the process. Partial and differential recovery of ceh1 hypocotyl growth under Rc in the presence of external auxin or ACC identifies auxin as the key growth-regulating hormone under these experimental conditions. Moreover, the measurement of hypocotyl growth of ceh1 seedlings introgressed into auxin and ethylene signaling receptor mutants places ethylene epistatic to auxin and supports a one-directional control mechanism of ethylene-auxin interaction under Rc conditions.

CONCLUSION

Here, we revealed MEcPP-mediated enhanced abundance of phyB, in part via the suppression of PIF4 and PIF5 expression levels, and the resulting reduced hypocotyl growth. We further established MEcPP-mediated coordination of phytochrome B with auxin and ethylene signaling pathways and the function of the collective signaling circuitries in the regulation of hypocotyl growth of red light-grown seedlings. In addition, hormonal applications and pharmacological treatments support the hierarchical functions of auxin and ethylene in regulating growth, with ethylene being epistatic to auxin.

In summary, this finding illustrates the MEcPP-mediated coordination of light and hormonal signaling cascades to ultimately reprogram plant growth in response to the light environment and further provides information on the functional hierarchy of these growth regulatory inputs. As such, this finding identifies plastids as the control hub of growth plasticity in response to environmental cues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) wild-type seedlings used here are the earlier-reported Col-0 ecotype transformed with HPL:LUC constructs and used as the parent (wild type) for isolation of the ceh1 mutant (Xiao et al., 2012). All experiments were performed with 7-d-old seedlings grown in 15 μE m−2 s−1 continuous monochromatic light at 22°C, unless specified otherwise. The ein3/eil1 double mutant was provided by Hongwei Guo (Southern University of Science and Technology); DR5-GFP was a gift from Mark Estelle (University of California, San Diego); and tir1-1 (CS3798) was ordered from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center.

Light Treatment

Surface-sterilized seeds were planted on one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (2.2 g L−1 MS salts, 1 g L−1 MES, pH 5.7, and 8 g L−1 agar), stratified at 4°C for 5 d, and grown in 15 μE m−2 s−1 light (monochromatic red, FRc, and blue light-emitting diodes; Quantum Devices Snap-Lite) in a custom chamber at ∼22°C for 7 d prior to hypocotyl measurement. Dark control experiments were performed by exposing seedlings to white light for 3 h after stratification, wrapping the plates with three layers of aluminum foil, and growing seedlings for 7 d before quantification of hypocotyl length. Each treatment was performed on three biological replicates, each replicate with 15 seedlings.

Hypocotyl Length Measurement

Seven-day-old seedlings were scanned with an Epson flatbed scanner, and hypocotyl length was measured using ImageJ.

RNA Isolation and RNA-Seq Library Construction

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Life Technologies) from 7-d-old seedlings grown in the dark and in Rc. The RNA quality and quantity were assessed by Nanodrop ND 1000 (Nanodrop Technologies); 4 µg of qualified total RNA was used for RNA-seq library preparation using Illumina’s TruSeq v1 RNA sample preparation kit (RS-930-2002) with a low-throughput protocol following the manufacturer’s instructions with modifications as described (Devisetty et al., 2014). Illumina’s 12 indices were used during adaptor ligation and library construction. The constructed libraries were size selected using a 1:1 volume of AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). The size and quality of libraries were examined using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). The 12 libraries were quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen ds DNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen) and equally pooled in one lane of single-end 50-bp sequencing in a HiSeq 2000 machine (Illumina) at the Quantitative Biosciences (QB3) facility at the University of California, Berkeley.

Quality Filtering and Alignment of RNA-Seq Data

To ensure good read quality for downstream analysis, raw reads were preprocessed using FastX-tool kit software (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) and custom Perl scripts. First, the demultiplexed raw reads were filtered with fastq_quality_filter with the following parameters (−q 20, minimum quality score to keep: 20; −p 95, minimum percentage of bases that must satisfy the quality score cutoff: 95). Next, reads with custom adapters were removed using a custom script. The quality of reads was examined before and after quality control with FastQC quality assessment software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Then, reads (1 × 50 bp) were mapped against the Arabidopsis representative_gene_model (TAIR10) using BWA v0.6.1-r104 (Li and Durbin, 2009) with parameters (-l 20) and SAMtools (Li et al., 2009). The resulting BAM files were used to calculate the read counts using a custom R script, and then the counts were used for differential gene expression analysis.

Differential Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Data

The edgeR Bioconductor package implemented in R was used to generate the pseudonormalized counts for visualization and to carry out differential gene expression analysis (Robinson et al., 2010). Genes were kept for further analysis if read counts were greater than one count per million in at least three of the 12 libraries. The edgeR generalized linear models framework with explanatory variables of genotype and treatment allowed us to specify a design matrix estimating the effect of run number (batch) as a nuisance parameter. After fitting the model for our experiment, we defined contrasts between parent lines (the wild type) and mutant (ceh1) in red light and tested for significant expression differences using a likelihood ratio test (glmLRT). P values for the remaining genes were adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for false discovery correction. Genes with a false discovery rate-adjusted P ≤ 0.01 were identified as differentially expressed.

MDS Plot

An MDS plot was generated in edgeR to analyze the relationship between samples. The distance between each pair of RNA-seq profiles corresponded to the average (root mean square) of absolute log fold change between each pair of samples.

GO Term Enrichment

The GOseq package in R (Young et al., 2010) was used to identify enriched GO terms (mainly biochemical process) in the differentially expressed gene list.

Hormones and Chemical Treatments

Surface-sterilized seeds were planted on one-half strength MS, stratified at 4°C for 3 d, germinated under Rc at 15 μmol m−2 s−1 for 2 d, and subsequently transformed to one-half strength MS with 1 g L−1 MES in combination with hormones or chemicals. These plates were vertically placed in Rc for another 5 d before hypocotyl measurements. IAA, ACC, auxinole, and NPA were dissolved in ethanol, water, dimethyl sulfoxide, and dimethyl sulfoxide, respectively. The corresponding solvents were used as control treatments (mock) for the respective experiments.

MEcPP and Hormone Measurements

The quantification of SA, JA, ABA, and IAA was carried out by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, using dihydro-JA, deuterated SA, ABA, and IAA as internal standards, respectively, as previously described (Savchenko et al., 2010). MEcPP extraction and quantification were performed as previously described (Jiang et al., 2019).

Microscopy

Confocal fluorescence imaging was performed using Zeiss LSM 710. GFP signal was examined in 7-d-old DR5-GFP and ceh1/DR5-GFP seedlings grown on one-half strength MS in Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1).

Immunolocalization of PIN1

Immunolocalization of PIN1 was performed using anti-PIN1 monoclonal primary antibody and fluorescein isothiocyanate anti-mouse secondary antibody as previously described (Jiang et al., 2018).

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from 7-d-old seedlings grown in Rc using TRIzol (Life Technologies) and treated with DNase to eliminate DNA contamination. One microgram of total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). At4g26410 was used to normalize target gene expression. Gene-specific primers were designed using the QuantPrime qPCR primer design tool (http://www.quantprime.de/) and are listed (Supplemental Table S2). Each experiment was performed with three biological replicates and three technical replicates.

Protein Extraction and Immunoblot Analyses

For protein extraction, 7-d-old seedlings were collected, ground with liquid nitrogen, homogenized in extraction buffer (10 mm HEPES, pH 7.6, 1 m Suc, 5 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm EDTA, 14 mm 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.4% [w/v] Triton X-100, 0.4 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μm MG132, 20 μm MG115, and proteinase inhibitor), centrifuged at 100,000g for 10 min at 4°C, after which supernatants were transferred to new tubes as total proteins. Then the proteins were separated on a 7.5% (w/v) SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Blots were probed with B1+B7 (1:500) primary antibodies obtained from Peter Quail’s lab. The secondary antibody was anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (KPL, catalog no. 074-1806; 1:10,000). Immunoblots for PIN1 protein were performed as previously described (Jiang et al., 2018) using anti-PIN1 monoclonal primary antibody (1:100) and secondary antibody anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (1:3,000). Chemiluminescent reactions were performed using the Pierce ECL Western Blotting Substrate following the manufacturer’s instructions. Excess substrate was removed from membranes before placing them between two plastic sheets to develop with x-ray and subsequently scanned with an Epson Perfection V600 Photo Scanner.

Statistical Analyses

All experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates. Data are means ± sd. The statistical analyses were performed using library agricolae, Tukey’s HSD test method in R with a significance of P < 0.05 (Bunn, 2008). We have specified the method we used for statistical analysis in all figure legends. The names and accession numbers of all genes named in this article are presented in Supplemental Table S1.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession number PRJNA601482.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Hypocotyl growth of ceh1 in Bc and FRc is phyB independent.

Supplemental Figure S2. Expression levels of PIF1, PIF3, PIF4, and PIF5 in wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1).

Supplemental Figure S3. MDS plot of sequencing data from 7-d-old wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1).

Supplemental Figure S4. Heat map of top 50 significantly enriched GO terms of down-regulated genes in ceh1/wild-type seedlings under Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1).

Supplemental Figure S5. Similar ABA and JA levels in wild-type and ceh1 seedlings grown in the dark and Rc (15 μE m−2 s−1).

Supplemental Table S1. List of differentially expressed genes.

Supplemental Table S2. List of primers used in RT-qPCR analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Derrick R. Hicks (University of Washington) for providing images of ethylene, IAA, and MEcPP stick chemical structures depicted in our model. We thank Meng Chen and Dr. Yongjian Qiu (University of California, Riverside) for providing the red light chamber and reagents for our experiments and Dr. Peter Quail (University of California, Riverside) for generously providing us with the phyB antibody. We thank Jacob North (University of California, Riverside) for all his efforts toward seedling preparation. We thank Dr. Geoffrey Benn (University of California, Riverside) for performing the statistical analyses using the R program.

Footnotes

This work was supported by HHS | NIH | National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant no. R01GM107311 to K.D.).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Bjornson M, Balcke GU, Xiao Y, de Souza A, Wang JZ, Zhabinskaya D, Tagkopoulos I, Tissier A, Dehesh K(2017) Integrated omics analyses of retrograde signaling mutant delineate interrelated stress-response strata. Plant J 91: 70–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunn AG.(2008) A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR). Dendrochronologia 26: 115–124 [Google Scholar]

- Chai T, Zhou J, Liu J, Xing D(2015) LSD1 and HY5 antagonistically regulate red light induced-programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 6: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenge-Espinosa M, Cordoba E, Romero-Guido C, Toledo-Ortiz G, León P(2018) Shedding light on the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP)-pathway: Long hypocotyl 5 (HY5)/phytochrome-interacting factors (PIFs) transcription factors modulating key limiting steps. Plant J 96: 828–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das D, St Onge KR, Voesenek LA, Pierik R, Sasidharan R(2016) Ethylene- and shade-induced hypocotyl elongation share transcriptome patterns and functional regulators. Plant Physiol 172: 718–733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Grauwe L, Vandenbussche F, Tietz O, Palme K, Van Der Straeten D(2005) Auxin, ethylene and brassinosteroids: Tripartite control of growth in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl. Plant Cell Physiol 46: 827–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devisetty UK, Covington MF, Tat AV, Lekkala S, Maloof JN(2014) Polymorphism identification and improved genome annotation of Brassica rapa through deep RNA sequencing. G3 (Bethesda) 4: 2065–2078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin PF, Yanovsky MJ, Kay SA(2003) A genomic analysis of the shade avoidance response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 133: 1617–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit M, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C(2014) Auxin-mediated plant architectural changes in response to shade and high temperature. Physiol Plant 151: 13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin KA, Lee SH, Patel D, Kumar SV, Spartz AK, Gu C, Ye S, Yu P, Breen G, Cohen JD, et al. (2011) Phytochrome-interacting factor 4 (PIF4) regulates auxin biosynthesis at high temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 20231–20235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gälweiler L, Guan C, Müller A, Wisman E, Mendgen K, Yephremov A, Palme K(1998) Regulation of polar auxin transport by AtPIN1 in Arabidopsis vascular tissue. Science 282: 2226–2230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldner N, Friml J, Stierhof YD, Jürgens G, Palme K(2001) Auxin transport inhibitors block PIN1 cycling and vesicle trafficking. Nature 413: 425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Cabanelas D, Wright LP, Paetz C, Onkokesung N, Gershenzon J, Rodriguez-Concepcion M, Phillips MA(2015) The diversion of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol-2,4-cyclodiphosphate from the 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway to hemiterpene glycosides mediates stress responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 82: 122–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliday KJ, Martínez-García JF, Josse EM(2009) Integration of light and auxin signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 1: a001586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Neve J, Hirose M, Kuboki A, Shimada Y, Kepinski S, Nozaki H(2012) Rational design of an auxin antagonist of the SCF(TIR1) auxin receptor complex. ACS Chem Biol 7: 590–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Tan X, Zheng N, Hatate T, Kimura Y, Kepinski S, Nozaki H(2008) Small-molecule agonists and antagonists of F-box protein-substrate interactions in auxin perception and signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 5632–5637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitschek P, Kohnen MV, Lorrain S, Rougemont J, Ljung K, López-Vidriero I, Franco-Zorrilla JM, Solano R, Trevisan M, Pradervand S, et al. (2012) Phytochrome interacting factors 4 and 5 control seedling growth in changing light conditions by directly controlling auxin signaling. Plant J 71: 699–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PJ, Hangarter RP, Estelle M(1998) Auxin transport is required for hypocotyl elongation in light-grown but not dark-grown Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 116: 455–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Rodriguez-Furlan C, Wang JZ, de Souza A, Ke H, Pasternak T, Lasok H, Ditengou FA, Palme K, Dehesh K(2018) Interplay of the two ancient metabolites auxin and MEcPP regulates adaptive growth. Nat Commun 9: 2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Zeng L, Ke H, De La Cruz B, Dehesh K(2019) Orthogonal regulation of phytochrome B abundance by stress-specific plastidial retrograde signaling metabolite. Nat Commun 10: 2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E(2014) PIFs: Systems integrators in plant development. Plant Cell 26: 56–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Monte E, Cohn MM, Quail PH(2012) Phytochrome signaling in green Arabidopsis seedlings: Impact assessment of a mutually negative phyB-PIF feedback loop. Mol Plant 5: 734–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leivar P, Quail PH(2011) PIFs: Pivotal components in a cellular signaling hub. Trends Plant Sci 16: 19–28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos M, Xiao Y, Bjornson M, Wang JZ, Hicks D, Souza A, Wang CQ, Yang P, Ma S, Dinesh-Kumar S, et al. (2016) The plastidial retrograde signal methyl erythritol cyclopyrophosphate is a regulator of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid crosstalk. J Exp Bot 67: 1557–1566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R(2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R(2009) The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X, Wang H, Mao L, Hu Y, Dong T, Zhang Y, Wang X, Bi Y(2012) Involvement of COP1 in ethylene- and light-regulated hypocotyl elongation. Planta 236: 1791–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli G, Ruberti I(2002) Light and shade in the photocontrol of Arabidopsis growth. Trends Plant Sci 7: 399–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy F, Schäfer E(2002) Phytochromes control photomorphogenesis by differentially regulated, interacting signaling pathways in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 53: 329–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negi S, Sukumar P, Liu X, Cohen JD, Muday GK(2010) Genetic dissection of the role of ethylene in regulating auxin-dependent lateral and adventitious root formation in tomato. Plant J 61: 3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni W, Xu SL, Chalkley RJ, Pham TN, Guan S, Maltby DA, Burlingame AL, Wang ZY, Quail PH(2013) Multisite light-induced phosphorylation of the transcription factor PIF3 is necessary for both its rapid degradation and concomitant negative feedback modulation of photoreceptor phyB levels in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 2679–2698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K, Devisetty UK, Lekkala S, Mueller-Moulé P, Bak A, Casteel CL, Maloof JN(2018) Network analysis reveals a role for salicylic acid pathway components in shade avoidance. Plant Physiol 178: 1720–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozue K, Harmer SL, Maloof JN(2011) Genomic analysis of circadian clock-, light-, and growth-correlated genes reveals PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING FACTOR5 as a modulator of auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 156: 357–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedmale UV, Huang SC, Zander M, Cole BJ, Hetzel J, Ljung K, Reis PAB, Sridevi P, Nito K, Nery JR, et al. (2016) Cryptochromes interact directly with PIFs to control plant growth in limiting blue light. Cell 164: 233–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail PH.(2002) Photosensory perception and signalling in plant cells: New paradigms? Curr Opin Cell Biol 14: 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausenberger J, Hussong A, Kircher S, Kirchenbauer D, Timmer J, Nagy F, Schäfer E, Fleck C(2010) An integrative model for phytochrome B mediated photomorphogenesis: From protein dynamics to physiology. PLoS ONE 5: e10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK(2010) edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26: 139–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Růzicka K, Ljung K, Vanneste S, Podhorská R, Beeckman T, Friml J, Benková E(2007) Ethylene regulates root growth through effects on auxin biosynthesis and transport-dependent auxin distribution. Plant Cell 19: 2197–2212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savchenko T, Walley JW, Chehab EW, Xiao Y, Kaspi R, Pye MF, Mohamed ME, Lazarus CM, Bostock RM, Dehesh K(2010) Arachidonic acid: An evolutionarily conserved signaling molecule modulates plant stress signaling networks. Plant Cell 22: 3193–3205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon MJ.(2003) The polar auxin transport inhibitor N-1-naphthylphthalamic acid disrupts leaf initiation, KNOX protein regulation, and formation of leaf margins in maize. Plant Physiol 133: 597–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellaro R, Pacín M, Casal JJ(2012) Diurnal dependence of growth responses to shade in Arabidopsis: Role of hormone, clock, and light signaling. Mol Plant 5: 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smalle J, Haegman M, Kurepa J, Van Montagu M, Van Der Straeten D(1997) Ethylene can stimulate Arabidopsis hypocotyl elongation in the light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 2756–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Yun J, Likhacheva AV, Alonso JM(2007) Multilevel interactions between ethylene and auxin in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell 19: 2169–2185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Ma Q, Mao T(2015) Ethylene regulates the Arabidopsis microtubule-associated protein WAVE-DAMPENED2-LIKE5 in etiolated hypocotyl elongation. Plant Physiol 169: 325–337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup R, Perry P, Hagenbeek D, Van Der Straeten D, Beemster GTS, Sandberg G, Bhalerao R, Ljung K, Bennett MJ(2007) Ethylene upregulates auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings to enhance inhibition of root cell elongation. Plant Cell 19: 2186–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Nakamura S, Mochizuki N, Nagatani A(2002) Phytochrome in cotyledons regulates the expression of genes in the hypocotyl through auxin-dependent and -independent pathways. Plant Cell Physiol 43: 1171–1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q, Uhlir NJ, Reed JW(2002) Arabidopsis SHY2/IAA3 inhibits auxin-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell 14: 301–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbussche F, Smalle J, Le J, Saibo NJ, De Paepe A, Chaerle L, Tietz O, Smets R, Laarhoven LJ, Harren FJ, et al. (2003) The Arabidopsis mutant alh1 illustrates a cross talk between ethylene and auxin. Plant Physiol 131: 1228–1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbussche F, Vaseva I, Vissenberg K, Van Der Straeten D(2012) Ethylene in vegetative development: A tale with a riddle. New Phytol 194: 895–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley J, Xiao Y, Wang JZ, Baidoo EE, Keasling JD, Shen Z, Briggs SP, Dehesh K(2015) Plastid-produced interorganellar stress signal MEcPP potentiates induction of the unfolded protein response in endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 6212–6217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JZ, Li B, Xiao Y, Ni Y, Ke H, Yang P, de Souza A, Bjornson M, He X, Shen Z, et al. (2017) Initiation of ER body formation and indole glucosinolate metabolism by the plastidial retrograde signaling metabolite, MEcPP. Mol Plant 10: 1400–1416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang KL, Li H, Ecker JR(2002) Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell 14(Suppl): S131–S151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Savchenko T, Baidoo EE, Chehab WE, Hayden DM, Tolstikov V, Corwin JA, Kliebenstein DJ, Keasling JD, Dehesh K(2012) Retrograde signaling by the plastidial metabolite MEcPP regulates expression of nuclear stress-response genes. Cell 149: 1525–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SF, Hoffman NE(1984) Ethylene biosynthesis and its regulation in higher-plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol 35: 155–189 [Google Scholar]

- Young MD, Wakefield MJ, Smyth GK, Oshlack A(2010) Gene Ontology analysis for RNA-seq: Accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol 11: R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Liu H, Klejnot J, Lin C (2010) The cryptochrome blue light receptors. The Arabidopsis Book 8: e0135, doi:10.1199/tab.0135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Wang J, Zhang Z, Quan R, Zhang H, Deng XW, Ma L, Huang R(2013) Ethylene promotes hypocotyl growth and HY5 degradation by enhancing the movement of COP1 to the nucleus in the light. PLoS Genet 9: e1004025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.(2012) Auxin biosynthesis: A simple two-step pathway converts tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid in plants. Mol Plant 5: 334–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S, Shi H, Xue C, Wang L, Xi Y, Li J, Quail PH, Deng XW, Guo H(2012) A molecular framework of light-controlled phytohormone action in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 22: 1530–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]