Abstract

Background:

Interpretation of thyroid function tests during pregnancy depends on gestational age, method, and population-specific reference intervals. Therefore, there is a worldwide trend to establish trimester-specific levels for different populations. The aim of this study was to establish a trimester-specific reference range for thyroid function parameters during pregnancy in Indian women.

Materials and Methods:

Thyroid function tests (TSH, FT4, TT4, TT3) of 80, 76, and 73 women at 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimester, respectively, and 168 nonpregnant women were analyzed after exclusion of low UIC(<150 μg/L) and anti-TPO positivity(>35 IU/ml). Urinary iodine excretion (UIC) was assessed in all. The 2.5th and 97.5th percentile values were used to determine the reference ranges for thyrotropin (TSH), free thyroxine (FT4), total thyroxine (TT4), and total triiodothyronine (TT3) for each trimester of pregnancy.

Results:

The reference range for TSH for first trimester was 0.19–4.34 μIU/ml, for second trimester 0.46–4.57 μIU/ml, and for third trimester 0.61–4.62 μIU/ml. The reference range during three trimesters for FT4 (ng/dl) was 0.88–1.32, 0.89–1.60, and 0.87–1.54, for total T4 (μg/dl) was 5.9–12.9, 7.4–15.2, and 7.9–14.9. In nonpregnant women, FT4 was 0.83–1.34, total T4 was 5.3–11.8, and TSH was 0.79–4.29. The mean UIC in nonpregnant women was 176 ± 15.7 μg/L suggesting iodine-sufficiency in the cohort.

Conclusion:

The trimester-specific TSH range in pregnant women in this study is not significantly different from nonpregnant reference range in the final phase of transition to iodine sufficiency in India.

Keywords: Pregnancy, reference interval, reference range, thyroid function tests, urinary iodine

INTRODUCTION

Overt hypothyroidism is associated with adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.[1] International guidelines have suggested that trimester-specific normative data for pregnant women need to be generated when interpreting thyroid function test results, as these parameters are dependent on a number of factors including iodine intake and autoimmune status. However, in the absence of local/regional data, it is suggested that TSH values as advocated by the American Thyroid Association and/or the Endocrine Society may be used as rough guidance for clinical decision making.[2,3] It is mentioned that TSH cut-off points were significantly lower during pregnancy as compared to nonpregnant states. Using these cut-offs, studies from India and elsewhere suggest a high prevalence of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy.[4,5,6,7,8,9]

Physiological changes associated with pregnancy such as increased serum thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), increased human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and increased renal iodine clearance alter thyroid function in pregnancy;[10] hence, nonpregnant cut-offs may not reflect the state of thyroid function during pregnancy appropriately. Apart from these, the transfer of iodine/thyroid hormone to fetus and increased activity of placental D3 deiodinase activity also modulate maternal thyroid hormone status. Hence, there is a need to establish population and trimester-specific references for thyroid function parameters during pregnancy.[2] Many other factors like manufacturer's methodology, ethnicity, gestational age, iodine status in the community, and selection of the reference population may also modify the reference intervals for thyroid function test reports in pregnancy.[11,12] The previous Indian studies over the last few decades have reported different reference intervals for thyroid function parameters in pregnancy.[4,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] India, like many other countries, is in a transition from iodine-deficient state to what we now believe an iodine-sufficient country. Hence, currently, the published data might not be useful in interpreting thyroid function test results during pregnancy accurately. In this background, we evaluated thyroid function test results and iodine status in pregnant women of different trimesters in an Indian cohort and attempted to establish trimester-specific normative values.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This crosssectional study was conducted in the Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism and Antenatal Clinic in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGME & R), Kolkata over a period of 1 year. The Institutional Ethics Committee at IPGMER approved the study protocol and informed written consent was obtained from study participants.

Three hundred pregnant women (100 from each trimester) aged 18–40 years having singleton pregnancy diagnosed at 8th week of pregnancy were consecutively recruited. Two hundred nonpregnant women (sisters, close relatives, or accompanying person of the pregnant women) were also recruited as control. All patients gave history of consuming iodized salt. After enrolment, a detailed history was taken and participants were clinically examined. Those who had a personal or family history of thyroid disorder, those who were on thyroid medications or had a history of liver dysfunction were excluded. Individuals with a history of hyperemesis gravidarum (first trimester only), having goitre 1B or more, palpable nodule were also excluded before enrolment in the cohort.

Serum thyrotropin (TSH), total thyroxin (TT4), free thyroxin (FT4), total triiodothyronine (TT3), antithyroid peroxidase antibody (anti-TPO antibody), and spot urinary iodine were measured. Subjects with the presence of anti-TPO antibody >35 IU/ml and low urinary iodine (<150 μg/L) were subsequently excluded in the recruited cohort for the analysis to establish normative reference values.

Lab methods

Serum and urine samples were immediately stored at −20°C for subsequent analysis. Serum TSH, FT4, TT4, TT3, and anti-TPO were estimated by the Chemiluminescence technique using commercially available kits from Siemens Diagnostics (Germany) with Immulite-1000 analyzer. The analytical sensitivity and total precision values for TSH, FT4, TT4, and TT3 assays were 0.01 μIU/ml and 2.2%, 0.35 ng/dl and 2.7%, 0.4 μg/dl and 2.5%, and 35ng/dl and 2.2%, respectively. The laboratory reference ranges were TSH (0.4–4 μIU/ml), FT4 (0.8–1.9 ng/dl), TT4 (4.5–12 μg/dl), TT3 (81–178 ng/dl), and the interassay coefficients of variation (CV) for the assays were 8.9%, 5.5%, 6.7%, and 9.3%, respectively. The corresponding values for interassay CV, total precision, and analytical sensitivity for anti-TPO were 10.5%, 7.6%, and 7 IU/ml. Anti-TPO Ab was considered elevated if levels were >35 IU/ml. Urinary iodine concentration (UIC) was determined in all participants by the ammonium persulfate method based on the Sandell–Kolthoff reaction. The interassay CV for UIC was 4%.[20] The UIC <150 μg/L in pregnant women was taken as evidence of insufficient iodine intake.[21]

Statistical analysis

The data was analyzed by SPSS (version 21.0; SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL, USA) using appropriate statistical tests. For descriptive statistics, frequencies, percentages, mean with standard deviations (SD), and median with interquartile range (IQR) of different variables were calculated. TSH, FT4, TT4, and TT3 data in reference population were calculated and expressed as 2.5th and 97.5th percentile to ascertain desired reference range. Independent sample t-test was used to compare the means of two separate sets. A P value threshold <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

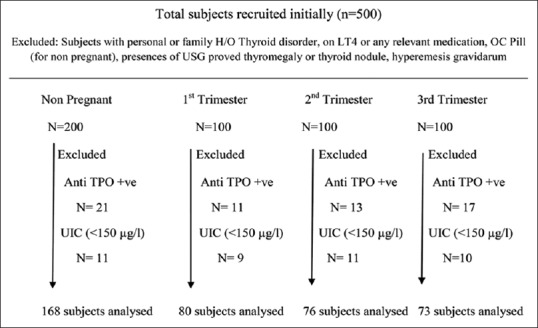

Three hundred pregnant women (100 women from each trimester) and 200 nonpregnant women were recruited initially. The distribution of subjects after exclusion of subjects with positive anti-TPO antibody and low UIC (<150 μg/L) was 80, 76, and 73 in 1st, 2nd, and 3rd trimester respectively. In the control group, 168 subjects were eligible for comparative analysis. Figure 1 demonstrates the flow chart for screening the subjects included in the study. All data except TSH were distributed normally as analyzed by Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subjects analyzed

Mean age of pregnant women was 24.6 ± 3.6 years (n = 229) and for the nonpregnant women it was 25.3 ± 3.8 years. About 42.3% (97/229) were multigravida and 57.7% (132/229) were primigravida. The mean (±SD) UIC in nonpregnant women (n = 200) was 176 ± 15.7 μg/L reflecting a state of iodine sufficiency in the cohort analyzed. UIC (μg/L) in different trimester was: 205 ± 16.9, 176 ± 14.9, and 182 ± 16.7, respectively. These baseline parameters are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the participants in this study

| 1st trimester (n=80) | 2nd trimester (n=76) | 3rd trimester (n=73) | Control (n=168) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean±SD) | 25±4.4 | 24±3.9 | 25 ± 3.8 | 25.3±2.9 |

| Primigravida | 47 (59%) | 41 (54%) | 44 (60%) | Nulliparous: 58 Multiparous: 110 |

| Mean UIC (μg/L) | 205±16. 9 | 176±14.9 | 182±16.7 | 178±13.9 * |

*The mean UIC in the whole nonpregnant cohort (n=200) was 176±15.7 μg/L

In non-pregnant women, FT4 was 0.83–1.34 ng/dl, total T4 was 5.3–11.8 μg/dl, and TSH was 0.79–4.29 μIU/ml. The trimester-specific reference interval of thyroid function tests (2.5th and 97.5th percentile) in pregnancy and in nonpregnant women, e.g., TSH, free T4, total T4, and total T3 in pregnant women in different trimesters and in nonpregnant women, is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Trimesterspecific reference interval (2.5th and 97.5th percentile) of thyroid function tests in pregnancy and in non-pregnant women

| TSH (μIU/ml) | Free T4 (ng/dl) | Total T4 (μg/dl) | Total T3 (ng/dl) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-pregnant | 0.79-4.29 | 0.83-1.34 | 5.3-11.8 | 83.2-178.8 |

| 1st Trimester | 0.19-4.34 | 0.88-1.32 | 5.9-12.9 | 86.2-245.8 |

| 2nd Trimester | 0.46-4.57 | 0.89-1.60 | 7.4-15.2 | 100-241.4 |

| 3rd Trimester | 0.61-4.62 | 0.87-1.54 | 7.9-14.9 | 91.3-238 |

Mean total T4 and total T3 levels were higher during week 12 to week 18, as compared to values in weeks 6–9 [for total T4 (μg/dl): 12.09 ± 1.57 vs 9.69 ± 2.45 (P < 0.001) and for total T3(ng/dl): 183 ± 25.5 vs145 ± 27.7 (P < 0.001)]. However, the mean total T4 and total T3 levels during week 12 to 18 weeks were not statistically different from values in 18–40 weeks [for total T4 (μg/dl): 12.09 ± 1.57 vs 11.83 ± 1.44 (P = NS) and for total T3(ng/dl): 183 ± 25.5 vs 172 ± 35 (P < 0.001)]. Unlike T4, free T4 did not increase; on the contrary, the levels decreased in 2nd trimester and were highly variable all through pregnancy. TSH trend showed a gradual rise as the pregnancy progressed, but did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Published data from studies on thyroid function in pregnancy are not similar. It is possible that the differences in TSH reference range among the studies are due to differing iodine health status in different communities. Urinary iodine excretion reflects iodine status in the population and hence may not reflect deficiency at the individual level.[2] We postulate that our population may still be in the possible final stages of transition into the state of iodine sufficiency.[22] In this background, our study may represent the most recent reference range of thyroid function parameters in Indian pregnant women. The results are in keeping with the ATA 2017 guidelines[2] and relatively similar to that suggested by Rajput et al.,[18] but differ from the previous Indian data by Marwah et al.[13] Lower limit of TSH in 1st trimester is similar to ATA 2017 guidelines and Jebasingh et al.,[15] but it is lower as compared to other Indian studies. The previous study from Kolkata used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique for measurement of TFTs. However, this method is seldom used nowadays.[19] Trimester-specific TSH values found in different Indian studies are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Trimester-specific TSH values found in different Indian studies

| References | Population | Thyrotropin reference range (mIU/L) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st trimester | 2nd trimester | 3rd trimester | ||

| ATA guideline 2011[25] | 0.1-2.5 | 0.2-3.0 | 0.3-3.0 | |

| Our Study | Kolkata 2016 | 0.19-4.34 | 0.46-4.57 | 0.61-4.62 |

| Marwah et al.[13] | Delhi 2008 | 0.6-5.0 | 0.44-5.78 | 0.74-5.7 |

| Maji et al.[19] | Kolkata 2013 | 0.25-3.35 | 0.78-4.96 | 0.89-4.6 |

| Sekhri et al.[14] | Delhi 2015 | 0.09-6.65 | 0.51-6.66 | 0.91-4.86 |

| Jebasingh et al.[15] | Manipur 2016 | 0.21-1.82 | 0.72-1.71 | 0.69-1.93 |

| Rajput et al.[18] | Haryana 2016 | 0.37-3.69 | 0.54-4.47 | 0.70-4.64 |

| Mankar et al.[17] | Nagpur 2016 | 0.24-4.17 | 0.78-5.67 | 0.47-5.78 |

There is no iodine deficiency in the analyzed cohort. As India is in a transition state of iodine sufficiency, ongoing improvement of iodine health may explain decreasing TSH reference range from the previous Indian data by Marwah et al., in which iodine status was not measured.[13] The study by Rajput et al. also did not check for maternal iodine status and it assumed Haryana to be an iodine sufficient area of India.[18] Recent data from Delhi and Nagpur did not report even a single case of iodine deficiency in pregnant women.[14,17] The median urinary iodine concentration of 150–200 μg/l during each trimester was reported in the study by Sekhri et al.[14] The present study also suggests that further improvement in iodine health is unlikely to change TSH reference range. Shi et al.[23] recently demonstrated a U-shaped relationship between urinary iodine concentrations and antibody positivity among pregnant women. We could not reproduce the same.

The study has some limitations. The sample size in our study was small. In addition, we did not follow up the same patients in all 3 trimesters as Sekhri et al., which intuitively sounds better to assess changes in thyroid function parameters during pregnancy. However, the study by Zhang et al. suggests that there is no significant difference was found between a self-sequential longitudinal reference interval and a cross-sectional reference interval.[24]

CONCLUSION

This study establishes the trimester-specific TSH, FT4, total T4, and total T3 hormone ranges in pregnant women from India during the final stage of transition to iodine sufficiency. However, the TSH levels of these patients were not different from those with optimal iodine status, implying that further correction of the same is unlikely to alter TSH levels.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate participant consent forms. In the form, the participants have given their consent for clinical information to be reported in the journal. The participants understand that their names will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by Endocrine Society of Bengal, a state affiliate to Endocrine Society of India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abalovich M, Gutierrez S, Alcaraz G, Maccallini G, Garcia A, Levalle O. Overt and subclinical hypothyroidism complicating pregnancy. Thyroid. 2002;12:63–8. doi: 10.1089/105072502753451986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander EK, Pearce EN, Brent GA, Brown RS, Chen H, Dosiou C, et al. 2017 Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and the postpartum. Thyroid. 2017;27:315–89. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Groot L, Abalovich M, Alexander EK, Amino N, Barbour L, Cobin RH, et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: An Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2543–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhanwal DK, Prasad S, Agarwal AK, Dixit V, Banerjee AK. High prevalence of subclinical hypothyroidism during first trimester of pregnancy in North India. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2013;17:281–4. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.109712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bocos-Terraz JP, Izquierdo-Álvarez S, Bancalero-Flores JL, Álvarez-Lahuerta R, Aznar-Sauca A, Real-López E, et al. Thyroid hormones according to gestational age in pregnant Spanish women. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:237–42. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karakosta P, Chatzi L, Bagkeris E, Daraki V, Alegakis D, Castanas E, et al. First- and second-trimester reference intervals for thyroid hormones during pregnancy in “Rhea” mother-child cohort, crete, Greece. J Thyroid Res. 2011;49:71–83. doi: 10.4061/2011/490783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan YQ, Dong ZL, Dong L, Wang FR, Yang XM, Jin XY, et al. Trimester and method-specific reference intervals for thyroid tests in pregnant Chinese women: Methodology, euthyroid definition and iodine status can influence the setting of reference intervals. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;74:262–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehran L, Amouzegar A, Delshad H, Askari S, Hedayati M, Amirshekari G, et al. Trimester-specific reference ranges for thyroid hormones in Iranian pregnant women. J Thyroid Res. 2013;2013:651517. doi: 10.1155/2013/651517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li C, Shan Z, Mao J, Wang W, Xie X, Zhou W, et al. Assessment of thyroid function during first-trimester pregnancy: What is the rational upper limit of serum TSH during the first trimester in Chinese pregnant women? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:73–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glinoer D. The regulation of thyroid function in pregnancy: Pathways of endocrine adaptation from physiology to pathology. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:404–33. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roti E, Gardini E, Minelli R, Bianconi L, Flisi M. Thyroid function evaluation by different commercially available free thyroid hormone measurement kits in term pregnant women and their newborns. J Endocrinol Invest. 1991;14:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03350244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La’ulu SL, Roberts WL. Second-trimester reference intervals for thyroid tests: The role of ethnicity. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1658–64. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.089680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marwah RK, Chopra S, Gopalakrishnan S, Sharma B, Kanwar RS, Sastry S, et al. Establishment of reference range for thyroid hormones in normal pregnant Indian women. Int J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;115:602–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sekhri T, Juhi JA, Wilfred R, Kanwar RS, Sethi J, Bhadra K, et al. Trimester specific reference intervals for thyroid function tests in normal Indian pregnant women. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2016;20:101–7. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.172239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jebasingh FK, Salam R, Meetei TL, Singh PT, Singh NN, Prasad L. Reference intervals in evaluation of maternal thyroid function of Manipuri women. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2016;20:167–70. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.176354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deshwal VK, Yadav A, Gogoi JB. Comparison of FT3, FT4 and TSH levels in pregnant women in Dehradun. J Acad Ind Res. 2013;2:239–44. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mankar J, Sahasrabuddhe A, Pitale S. Trimester specific ranges for thyroid hormones in normal pregnancy. Thyroid Res Pract. 2016;13:106–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajput R, Singh B, Goel V, Verma A, Seth S, Nanda S. Trimester-specific reference interval for thyroid hormones during pregnancy at a tertiary care hospital in Haryana, India. Indian J Endocr Metab. 16;2:810–5. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.192903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maji R, Nath S, Lahiri S, Saha Das M, Bhattacharyya AR, Das HN. Establishment of trimester-specific reference intervals of serum TSH and fT4 in a pregnant Indian population at North Kolkata. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2014;29:167–73. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0332-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi T, Yamaki M, Pandav CS, Karmarkar MG, Irie M. Simple microplate method for determination of urinary iodine. Clin Chem. 2000;46:529–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Urinary iodine concentrations for determining iodine status in populations. [Last accessed on 2019 Aug 12]. Available from: https://appswhoint/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85972/WHO_NMH_NHD_EPG_131_engpdf;jsessionid=7199D37A5DDA64E474F78CB14 F8A 0904sequence=1 .

- 22.Chandwani HR, Shroff BD. Prevalence of goiter and urinary iodine status in six-twelve-year-old rural primary school children of Bharuch District, Gujarat, India. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:54–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi X, Han C, Li C, Mao J, Wang W, Xie X, et al. Optimal and safe upper limits of iodine intake for early pregnancy in iodine-sufficient regions: A cross-sectional study of 7190 pregnant women in China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:1630–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, Yao B, Li C, Mao J, Wang W, Xie X, et al. Reference intervals of thyroid function during pregnancy: Self-sequential longitudinal study versus cross-sectional study. Thyroid. 2016;26:1786–93. doi: 10.1089/thy.2016.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stagnaro-Green A, Abalovich M, Alexander E, Azizi F, Mestman J, Negro R, et al. American thyroid association taskforce on thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum 2011 guidelines of the American thyroid association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 21:1081–125. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]