Abstract

Introduction

Dyspareunia can be a debilitating symptom of endometriosis. We performed this study to examine women’s experiences with painful sexual intercourse, the impact of dyspareunia on patients’ lives, and perceptions of interactions with healthcare practitioners.

Methods

An anonymous 24-question online survey was provided through the social media network MyEndometriosisTeam.com and was available internationally to women aged 19–55 years who were self-identified as having endometriosis and had painful sexual intercourse within the past 2 years.

Results

From June 13 to August 20, 2018, 860 women responded and 638 women completed the survey (United States, n = 361; other countries, n = 277; 74% survey completion rate). Respondents reported high pain levels (mean score, 7.4 ± 1.86; severity scale of 0 [no pain] to 10 [worst imaginable pain]), with 50% reporting severe pain [score of 8 to 10]). Nearly half (47%) reported pain lasting ≥24 hours after intercourse with the pain often leading to avoiding (34%) or stopping (29%) intercourse. Pain impacted patients’ lives, causing depression (61%), anxiety (61%), low self-esteem (55%), and relationship strain. Many women feared to seek help (10%). Of those women who approached practitioners, many (36%) did not receive effective treatments.

Discussion

Women with dyspareunia related to endometriosis experience severe pain that can negatively impact patients’ lives. Dyspareunia may be a challenging topic for discussion for both patient and practitioner, leading to a suboptimal treatment approach and management. Results suggest that practitioners need improved education and training regarding dyspareunia to evaluate and treat patients’ sexual pain caused by endometriosis.

Keywords: dyspareunia, endometriosis, patient satisfaction

Introduction

Endometriosis impacts approximately 6–10% of women of childbearing age, with a higher prevalence among infertile women (38%) and women with chronic pelvic pain (71–87%).1 Pain during intercourse (ie, dyspareunia) is one of the most common pain symptoms associated with endometriosis, impacting 30–70% of women with the disorder.2–5 Repetitive experiences with pain during intercourse may cause women with symptomatic endometriosis to fear sexual intimacy, leading to a negative cycle of reduced sexual arousal, desire, satisfaction, ability to orgasm, and extreme pain.6,7 The fear and downstream effects caused by dyspareunia may ultimately lead to sexual dysfunction and exact a heavy emotional, psychological, and physical toll on patients.7 Dyspareunia is consequently associated with decreased quality of life, anxiety, depression, and poor self-esteem.3,8,9 In addition, dyspareunia can negatively impact a patient’s life course. For example, it can cause strained intimate relationships or even negatively influence a woman’s decision to start a family.5,8,10,11

Experiences with dyspareunia are further complicated by the societal stigma surrounding topics such as menstruation and painful sexual intercourse and the societal normalization of painful sexual intercourse in women. Women may be too embarrassed to discuss their sex life with a physician, especially if talking to a male physician, so they cope with this situation in silence or even tend to normalize the painful intercourse, leading to a delay in diagnosis and treatment.12–14 Studies estimate that roughly two-thirds of women distressed by sexual problems do not seek medical help.15,16 Diagnosis and treatment of dyspareunia may be further hindered because practitioners tend to avoid discussing a patient’s sexual health.14,17,18 Sobecki et al report that only 40% of obstetrician/gynecologists routinely discuss a patient’s sexual problems.13 Physicians across different specialties may shy away from these discussions because of cultural differences.13

The tremendous impact of dyspareunia on a patient’s quality of life and the tendency of women to not receive needed treatments because of failures in patient/practitioner communication are specific reasons to establish better management practices. However, few studies have sought patient experiences with dyspareunia, despite its recognition as a neglected research area by the World Endometriosis Society.7,19,20 Whereas there have been intriguing in-depth studies that examine dyspareunia, most of these studies report on women who have superficial/provoked dyspareunia not directly related to the deep dyspareunia associated with endometriosis.7 For example, existing research shows that provoked vestibulodynia, the most common cause of pain during sexual intercourse in women aged 30 years and younger, can have a negative impact on sexual quality of life, psychological health, relationships, and patient/practitioner interaction.17,21-23

Physicians who are understanding of women’s perspectives and are respectful of their individual needs, values, and preferences could ensure better patient-centered management of dyspareunia and endometriosis. The goal of this multicountry cross-sectional study was to define the social and emotional impact of endometriosis-related dyspareunia by examining women’s experiences with pain during intercourse, the impact of dyspareunia on their lives, and perceptions of interactions with their practitioners.

Methods

Survey Development

An anonymous online survey was developed through a partnership between AbbVie and MyHealthTeams, a company that creates social networks for people living with or caring for someone with a chronic condition. These networks foster discussion and provide a sense of community and support among people with similar conditions. The survey was approved by an Advarra institutional review board (Columbia, Maryland) for subjects in the United States and was conducted online from June 13 through August 20, 2018.

Survey questions were developed based on online communications between members of MyEndometroisisTeam.com, a MyHealthTeams social network created for women living with endometriosis. Discussion themes on the social network (ie, experiences with dyspareunia-related pain, the impact of dyspareunia on life, and interactions with healthcare practitioners) were used to create 24 survey questions about women’s experiences with dyspareunia. Statements presented to participants for their response were rotated to avoid any bias introduced by response selections. Most survey questions were closed ended with answer options provided to participants, and one question was open ended and allowed participants to provide personal advice, tips, or questions for other women experiencing dyspareunia. Survey questions and answers are provided in the Supplementary Material. Before finalization of the survey, a trial version was provided to 12 women living with endometriosis (sample population) who were outside of the MyEndometriosisTeam.com social network but were representative of the demographics found within the network. Eight women provided feedback on whether the questions were clear and relatable.

Participant Eligibility and Recruitment

Women who were subscribers to the MyEndometroisisTeam.com social media network were recruited through survey invitation emails and a reminder email. Additional participants completed the survey through invitations posted on the network’s public Facebook. The English-language survey was completed by an international population of women aged 19–55 years who self-identified as having endometriosis and had felt pain during sex within the past 2 years. The survey was anonymous and answers could not be tied to individual subscribers to the social network.

Survey Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to tabulate survey responses in this cross-sectional study. Responses were evaluated for the entire population, and evaluated separately as the United States population and the rest of the world. One-tailed and two-tailed Student’s tests with a 95% confidence significance level (α=0.05) were conducted to determine any differences between respondents in the United States and the rest of the world.

Results

Survey Response and Demographics

Approximately 45,000 women were invited. There was a 6% open rate and an 11% click-through rate to the survey itself; 638 women completed the survey, which was live from June 13 to August 20, 2018. Of the 638 women, 361 (57%) responded from within the United States and 277 (43%) responded from other countries with high numbers of English speakers, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, Ireland, New Zealand, and the Netherlands (Table 1). Women ranged in age from 19–55 years, with 516 of 638 patients (81%) younger than 39 years. Of the 638 women, 375 (59%) self-reported being unsure of the stage of their disease and 143 (22%) self-reported having stage 4 disease. More women in the United States were unsure of their stage than were women living outside the United States (62% [225 of 361] of US respondents, 54% [150 of 277] of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level). Women reported living with endometriosis-related pain for 2 to 38 years, with an average (SD) of 11.9 ± 7.33 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics

| Characteristics | Respondents, n (%) (N = 638) |

|---|---|

| Age at Time of Survey, Years | |

| 19–29 | 252 (39) |

| 30–39 | 264 (41) |

| 40–49 | 116 (18) |

| 50–55 | 6 (1) |

| Country | |

| Australia | 47 (7) |

| Canada | 42 (7) |

| Ireland | 10 (2) |

| Netherlands | 1 (0.2) |

| New Zealand | 14 (2) |

| South Africa | 31 (5) |

| United Kingdom | 113 (18) |

| United States (excluding Puerto Rico) | 361 (57) |

| Other | 19 (3) |

| Type of Endometriosis | |

| Stage 1 | 24 (4) |

| Stage 2 | 43 (7) |

| Stage 3 | 53 (8) |

| Stage 4 | 143 (22) |

| Not sure | 375 (59) |

| Years Living with Endometriosis-Related Pain | |

| Mean (SD) | 11.9 (7.33) |

| Median (range) | 10 (2–38) |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Women’s Experiences with Pain During Sexual Intercourse

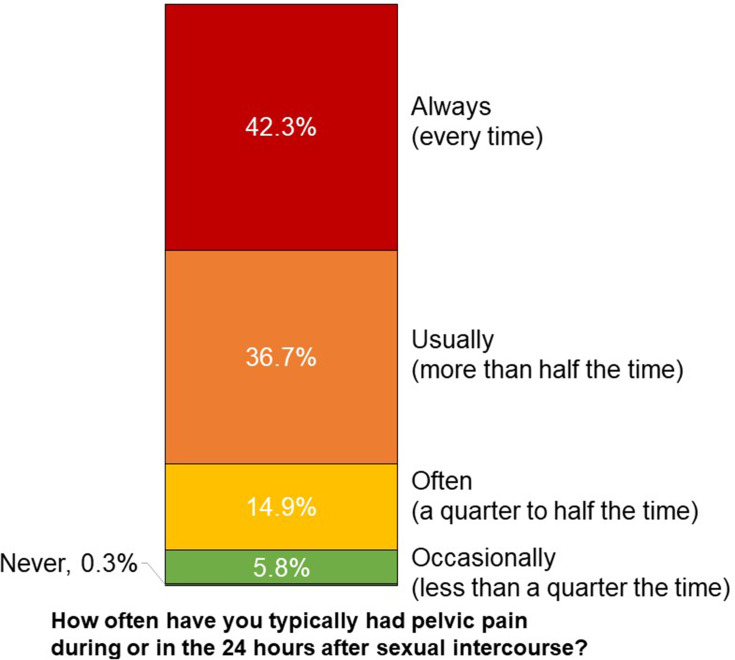

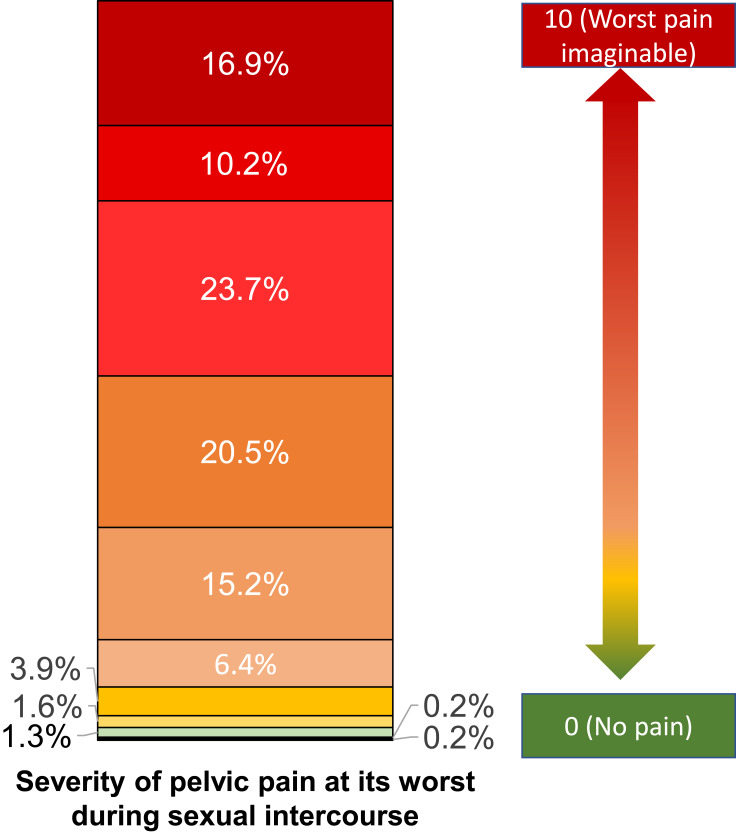

All women who responded to the survey felt pain during sexual intercourse at sometime within the past 2 years. Of the 638 women, 504 (79%) reported they usually or always experienced pain during intercourse (Figure 1). Women reported this pain began early, with 281 of the 638 respondents (44%) experiencing pain when they first began sexual activity. When asked to rate their pain on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst imaginable pain, women reported an average (SD) pain of 7.4 ± 1.86 when the pain was at its worst during intercourse within the past 2 years (Figure 2). Women also reported that pain lingered after sexual intercourse, with 302 of 638 women (47%) indicating that pain lasted for 24 hours or more after intercourse.

Figure 1.

Frequency of pelvic pain related to sexual intercourse. Respondents were asked to describe the frequency of pelvic pain during or in the 24 hours after sexual intercourse.

Figure 2.

Severity of pelvic pain at its worst during sexual intercourse. Respondents were asked to rate their worst pain during sexual intercourse on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst imaginable pain).

Of the 638 women, 492 (77%) described their pain during sexual intercourse as “stabbing,” 449 (70%) used “cramping”, and 346 (54%) used “aching”. A total of 295 of 638 women (46%) reported intercourse was most painful in the few days before, during, or after their periods and 255 of 638 women (40%) reported it was painful all month long. The pain was felt in the pelvic/abdominal area in 521 of 638 women (82%) and deep inside the vagina in 423 of 638 women (66%). Meanwhile, 203 of 638 women (32%) felt their pain at the entrance of the vagina. Pain onset was mainly during deep penetration in 345 of 638 women (54%). This pain made 448 of 638 women (70%) find sexual intercourse unpleasant. A total of 216 of 638 women (34%) reported always or usually avoiding intercourse with their partners while 188 of 638 women (29%) reported needing to stop intercourse due to pain severity.

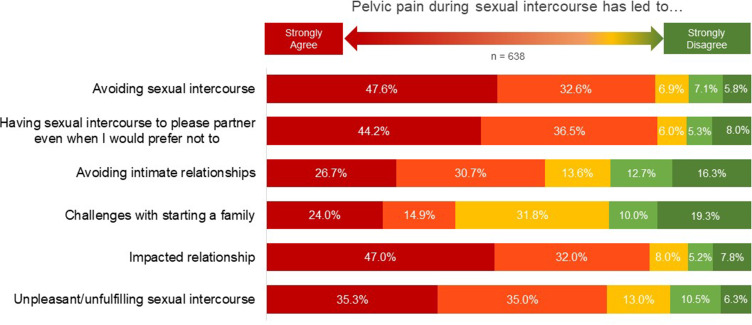

Impact of Dyspareunia on Patients’ Lives

Respondents indicated that dyspareunia had a distinct negative impact on their lives. Of the 638 women, the pain during sex caused low self-esteem in 353 (55%) and feelings of unattractiveness in 412 (65%), depression in 392 (61%), anxiety in 392 (61%), insecurity in 377 (59%), inadequacy in 363 (57%), guilt in 346 (54%), embarrassment in 337 (53%), and unfulfillment in 301 (47%). Dyspareunia also impacted women’s relationships (Figure 3). The pain caused 366 of 638 women (57%) to somewhat or strongly agree that the pain caused them to avoid being involved in intimate relationships, and 254 of 638 women (40%) said that the pain had an impact on their relationship with a spouse or significant other. Of the 638 women, 407 (64%) reported that they feared their dyspareunia would cause their spouse or partner to leave them or feel unfulfilled and 251 (39%) worried that they would never be able to have children.

Figure 3.

Impact of dyspareunia on various aspects of patients’ lives. Respondents were asked to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed their endometriosis interfered with sexual intercourse, their relationships, and family plans.

A total of 495 of 638 women (78%) spoke to their partners about painful sexual intercourse. Of the 495 women who spoke with their partners, 156 (32%) felt their spouse or partner was not understanding enough about their pain during intercourse. More women in the United States reported their partner was not understanding enough about their pain during intercourse than women outside the United States (97 of 277 or 35% of US respondents, 61 of 218 or 28% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level).

Women’s Experiences with Their Healthcare Practitioners and Treatment

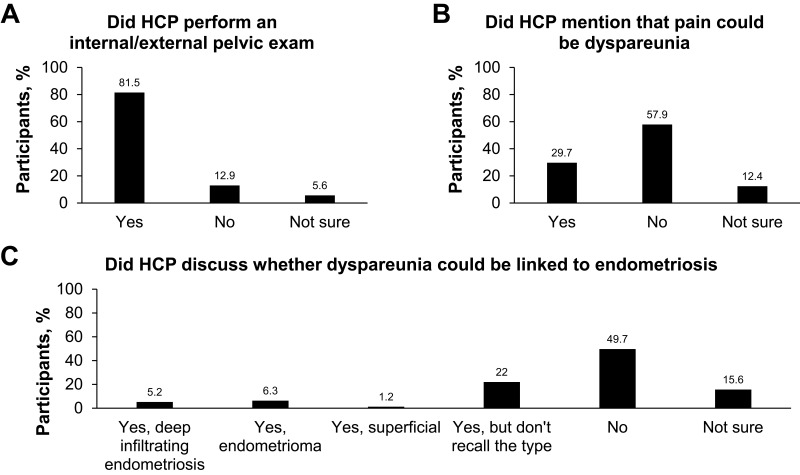

Two questions explored whether women spoke to practitioners about painful sexual intercourse. The first question (Question 7 in Supplementary Material 1) asked with whom women spoke, and multiple selections could be made among a range of responses that included a doctor, nurse practitioner, family, friends, or other types of acquaintances, indirectly allowing women to reveal whether or not they had spoken to a healthcare practitioner. A total of 496 of 638 women (78%) said they spoke to their doctors about painful sexual intercourse. In this question, women in the United States were also more likely to speak to a nurse about their pain than women outside the United States (27% [96 of 361] of US respondents, 15% [42 of 277] of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level). A second question (Question 15 in Supplementary Material 1) directly asked which types of healthcare professionals, if any, women spoke with about painful sexual intercourse. Multiple selections could be made from a variety of responses that included different healthcare workers or “none.” A total of 572 of 638 women (90%) selected at least one type of healthcare practitioner, once again constituting the majority of women. The other most frequently selected types of professionals spoken to about painful sexual intercourse in this question were “gynecologist” by 418 of 638 women (66%) and “OB-GYN” by 316 of 638 women (50%). Furthermore, 528 of 638 women (83%) included one of both of these selections in their response. In this question, women in the United States were also more likely to speak to a primary care physician (111 of 361 or 31% of US respondents, 43 of 277 or 16% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level) and less likely to speak to a family practitioner (42 of 361 or 12% of US respondents, 85 of 277 or 31% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level) than women outside the United States. Effectively administered pelvic examinations are an important step in identifying the source of women’s pain during sexual intercourse, building rapport with patients, and educating women about their condition.24,25 These examinations also allow providers to assess tenderness and nodularity, which is closely related to deep infiltrating endometriosis that has been reported to be associated with dyspareunia.26 Of the 572 women who did speak to a healthcare practitioner, 466 (81%) said that their practitioner conducted a pelvic examination as part of the process of identifying the source of their pain (Figure 4A). Women in the United States were also more likely to receive a pelvic examination (86% [274 of 318] of US respondents, 76% [192 of 254] of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level). A total of 331 of the 572 women (58%) said that their healthcare practitioner did not tell them that the pain they felt could be the medical condition called dyspareunia (Figure 4B), and this response was more common for women outside the United States (171 of 318 or 54% of US respondents, 160 of 254 or 63% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level). Furthermore, 284 of 572 women (50%) who were told about dyspareunia were not told that it could be linked to their endometriosis (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Experience with dyspareunia diagnosis. Women were asked (A) if their practitioner conducted a pelvic examination during the process of identifying the source of their pain, (B) if the pain they felt during sexual intercourse could be the medical condition dyspareunia, and (C) whether their practitioner discussed that their painful sexual intercourse could be linked to a certain type of endometriosis.

Of the 66 of 638 women (10%) who did not speak to a healthcare practitioner about pain they experienced during sexual intercourse, 34 of 66 (52%) cited that they did not talk to their practitioner because they were too embarrassed or uncomfortable discussing the topic and 31 of 66 (47%) believed they could not be helped. Of all 638 respondents, 264 (41%) said they would find it easier to talk about their pain to a female practitioner, 285 (45%) said it would be easier to talk to a practitioner that initiated the conversation, and 195 (31%) said a practitioner that shared examples of other women that had similar experiences would be easier. Of the 572 women who saw a practitioner, 242 (42%) were recommended surgery, 184 (32%) were recommended over-the-counter medications, and 181 (32%) were recommended lubricants. More women from the United States than outside the United States reported their practitioners recommended surgery (146 of 318 or 46% of US respondents, 95 of 254 or 37% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level) and physical therapy (49 of 318 or 15% of US respondents, 24 of 254 or 9% of non-US respondents; 95% confidence level). Prescription medication to lessen pain attributed to dyspareunia was recommended to only 33 of 572 women (6%). Over one-third of women, or 228 of 638 (36%), reported that nothing they have tried on their own or by recommendation of a practitioner has helped with their pain.

Discussion

Surveyed women experienced painful sex that negatively impacted various aspects of their lives. Encouragingly, the majority of women felt comfortable enough to approach practitioners about their symptoms, but many women struggled to receive adequate information and effective treatments. The overall results did not show overt numerical differences among respondents that lived both inside and outside the United States for most questions. Among surveyed women with endometriosis-related dyspareunia, most reported that they always or usually experience pain. Nearly half experienced pain lasting 24 hours or more after sex, with women reporting high pain levels on a pain severity scale, and having to either stop or avoid intercourse because of the pain. Interestingly, women in this study reported much higher pain levels during intercourse based on the severity scale than did women in previous studies, although rates of disruption or avoidance of sexual intercourse and duration of pain after sex were similar.9,27 The higher level of pain experienced by women in our study could be explained by the fact that our sample was sourced from an online support network of women. These types of patient-centered support networks may increase the likelihood of drawing women who are seeking support and therefore struggling more in some way with their condition.3 Although pain severity is only marginally correlated with disease stage, it is possible that more women with deep infiltrating endometriosis participated in our survey as this population has a higher prevalence of dyspareunia.28,29 Similarly, the higher pain severity could be explained by having more women in the social media network struggling with mood disorders, which are known to amplify pain severity.28 However, the survey-based nature of our data and limited information make it impossible to accurately determine the degree of endometriosis and dyspareunia from our study population.

Dyspareunia negatively impacted women’s emotional health and social relationships, leading to feelings of depression and anxiety, poor self-esteem, and concerns that partners would leave because of the woman’s dyspareunia. Our finding that dyspareunia has a negative impact on mental health agrees with findings reported in previous studies. In an observational cross-sectional study, 59% of women with endometriosis who completed a patient health questionnaire had a psychiatric disorder (eg, depression), which was significantly correlated with pain symptoms.30 Other studies have also reported that women with endometriosis experience problems with depression/anxiety, problems with usual activities, and an overall reduction in quality of life.31–33 Studies specifically focused on sexual function or dyspareunia related to endometriosis have reported similar trends in depression, anxiety, and issues with self-esteem, along with stress on personal relationships.8,9,34

One of every 10 women did not approach her healthcare practitioner about her pain due to embarrassment or other reasons, and most women said having their provider initiate the conversation would have helped make them more comfortable. This suboptimal communication reported between women and their healthcare practitioners was troubling and underlines a need for broader medical education about dyspareunia related to endometriosis and training on how practitioners can improve patient communication. The results are consistent with findings from other studies that examined communications between women with sexual dysfunctions and their healthcare practitioners, where approximately 78–80% of women reported they prefer practitioners to broach these topics.15,16 There is a documented hesitancy in healthcare practitioners to discuss patient sexual health and a tendency to not routinely discuss patients’ sexual problems due to fear of embarrassing their patients or themselves, insufficient time or training, or religious beliefs.13 In this study, even when women did talk to their practitioner about their pain, communication remained inefficient, with most women not being told their pain could be the medical condition dyspareunia or that it could be related to their endometriosis.

The observed disconnect between patients and their practitioners in discussing, diagnosing, and managing dyspareunia underlines the importance of additional medical training in these areas. Arming practitioners with effective strategies to discuss sensitive subjects with patients could be one method to improve overall healthcare. For example, questions should be asked several times and in different ways to ensure that accurate answers are collected from patients because the taboo surrounding sexual health may make patients initially less forthcoming in their responses.35 Listening to how patients describe their pain is also important, including its description, duration, localization, and timing. For example, women in our study most frequently localized their pain to the abdomen/pelvis and said that their pain was connected to their menstrual cycle, which are recognized clues of dyspareunia linked to endometriosis.24,36

Although most women in this study said their practitioners included a pelvic examination in the process of identifying the source of their pain, a notable 13% of women said that they did not receive a pelvic examination. This is troubling since pelvic examinations are a critical step to identify the source of women’s pain during sexual intercourse. When educational pelvic examinations are done correctly, they can also build rapport between patients and practitioners and empower patients by teaching them about their condition.24 Conversely, negative experiences with pelvic examinations that are rushed or painful can be traumatic for patients and may cause some women to avoid seeking future medical care and treatment.25 Furthermore, these pelvic examinations can help differentiate dyspareunia that may be directly related to endometriosis or a concurrent condition, such as provoked vestibulodynia or pelvic floor myalgia. Dyspareunia linked to endometriosis is most often deep in contrast to the superficial dyspareunia related to provoked vestibulodynia.28 Most women (82%) in our study said they felt their pain deep in their vagina while 32% felt pain at the entrance of their vagina. The ability to identify dyspareunia early through ongoing patient discussions and a targeted physical examination, complemented by ultrasound imaging, could provide pain relief for patients sooner and improve their overall healthcare experience.24

Our study and others3,8,9 indicate that women’s experiences with dyspareunia can negatively impact the lives of patients and may be associated with anxiety, depression, and poor self-esteem, highlighting a need for effective disease management. A previous study that used a sample population recruited from the same social media network found that the majority of women (61.5% in the United States and 69.4% outside the United States) were disappointed with their healthcare practitioner. This previous study also found that the treatment goals of practitioners were usually not aligned with women’s own goals and needs.37 These findings complement results from our current study, which suggest that women may not be getting sufficient information about their dyspareunia or effective treatments to mitigate their pain and lessen the negative impact painful sex has on daily lives. Indeed, 36% of surveyed women reported that the medical advice provided by their healthcare practitioner was ineffective in addressing their pain. Whereas the details of the medical advice provided to the participants are not clear, the benefits of surgical and medical methods to improve dyspareunia are well documented.7 Many women in our study (42%) reported their healthcare practitioners recommended surgery.7 In addition to pelvic floor physical therapy and psychological therapies,38 a variety of medications to lesson dyspareunia are also available. However, women in our study reported that healthcare practitioners rarely recommended these treatments. Ospemifene (Duchesnay USA, Rosemont, Pennsylvania) and prasterone (AMAG Pharmaceuticals Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) were the two medications indicated for dyspareunia that were most frequently prescribed to patients in our study, but they have not been studied extensively in a younger population of women with endometriosis.39 Combined oral contraceptives can also be effective in relieving pain, but they do come with some negative sexual effects and may lead to mood disorders in some women.7 Elagolix (AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, Illinois, USA) is an additional medication for the treatment of dyspareunia and other endometriosis-associated pain and was recently approved in the United States and Canada. This medication has been found to improve women’s pain and quality of sexual relationships.40 Although medications may be effective, they can be cost prohibitive since out-of-pocket costs can total to thousands of dollars for the uninsured over the course of a year.41,42 Even the $15 to $50 monthly out-of-pocket costs for oral contraceptives are not trivial for many women.43 Educating practitioners about these and other treatment options and encouraging them to listen to patient needs may help more women find a treatment option that works for their unique needs. Patients who are satisfied with their healthcare have also been shown to be more likely to continue visiting their practitioner and adhere to prescribed treatments.44,45

Similarly, multidisciplinary care may also improve patients’ experiences with endometriosis and dyspareunia. In this approach, healthcare practitioners from different specialties collaborate to complement medical treatments and manage various facets of a patient’s pain and overall well-being. These teams could include gynecologists, pelvic floor physical therapists, sexual therapists, mental health providers, and other professionals.28,38 This multidisciplinary approach has already been shown to be effective at treating superficial dyspareunia linked to vulvodynia and other conditions.38,46

The social media network used in this study garnered a meaningful sample size of women from countries around the world. Information taken from the platform also helped us identify patterns and develop themes in discussions with MyEndometriosisTeam.com members, which helped inform the development of targeted survey questions. Use of a network that women trust also enabled an in-depth analysis of a sensitive topic that both patients and practitioners alike are hesitant to talk about in the clinic.12,13 Although the social media network provided distinct advantages, it was also accompanied by the limitation that surveyed women may not represent the demographics of the general population.47–49 Additionally, all respondents experienced pain during sexual intercourse in the past 2 years and no control group was used in the study. Furthermore, MyEndometriosisTeam.com is a patient-centered platform that aims to provide struggling patients with a support network. Although the platform enabled a large sample size from multiple countries, these patient-centered groups may be more likely to draw women who join the network for support because they have struggled more or longer with their disease than the average patient with endometriosis, potentially introducing sample bias into our study. For example, one recent study found that populations acquired from similar patient networks may be more likely to report a reduced quality of life because of endometriosis.48 The responses are further compounded by possible nonresponse bias in what types of participants may be more driven to respond to a voluntary survey.50 It is plausible that women with especially negative experiences could be more motivated to respond. This survey was also provided only in English, prohibiting the participation of non-English speakers living with dyspareunia around the world. Additionally, this survey relied on women self-reporting endometriosis, which is less accurate than relying on register data. However, research suggests that self-reported information on endometriosis may be useful and moderately accurate when inpatient register data are not available.51 Similarly, this study relied on patient recollection and personal opinions of their disease instead of objective medical reports. Finally, our study did not have a non-endometriosis control group and did not report comorbidities (such as interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome or myofascial pain syndrome) that could lead to dyspareunia in surveyed women with endometriosis.7

In conclusion, women self-reporting endometriosis in this international online survey experienced painful sex that had a substantial impact on their lives and relationships. Nevertheless, healthcare practitioners too frequently offered limited information to women about their condition and advice for relief. Furthermore, an initiation of dialogue by healthcare practitioners may allow for earlier recognition of painful sexual intercourse and the impact it has on the lives of patients. Barriers to open dialogue may limit receipt of medical treatment needed for sexual pain. The social and emotional impact of dyspareunia combined with the suboptimal communication observed with healthcare practitioners highlights a need for broader medical education about dyspareunia in patients with endometriosis, its treatment options, and effective methods to discuss sensitive subject material with patients.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, funded by AbbVie, was provided by Michael M. Schofield, PhD, and Kelly Cameron, PhD, CMPP™, of JB Ashtin, who developed the first draft based on an author-approved outline and assisted in implementing author revisions. An abstract of this paper was presented at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 68th Annual Clinical and Scientific Meeting as a poster presentation with interim findings, and was published in “Poster Abstracts” in Obstetrics & Gynecology: May 2019 – Volume 133 -Issue – p1-2 doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000559306.07093.6a. An abstract of this paper was also presented at the Society of Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders as a conference talk with interim findings.

Funding Statement

Financial assistance in developing the survey and collecting data was provided by AbbVie Inc. In partnership with MyHealthTeams, AbbVie participated in the interpretation of data, review, and approval of the manuscript, and was involved in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymized, individual and trial-level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (e.g., protocols and Clinical Study Reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and execution of a Data Sharing Agreement (DSA). Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html.

Author Contributions

Oscar Antunez Flores and Beth Schneider were involved in the concept/design of the study, Beth Schneider was involved in the data acquisition, Roberta Renzelli-Cain and Beth Schneider were involved in the statistical analysis, and all authors contributed to the data interpretation, drafting and revising the manuscript, provided final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

K Witzeman is on the executive board of directors for the International Pelvic Pain Society and is the sole owner of Pelvic Health Educational Services, LLC. O Antunez Flores is a full-time employee of AbbVie and may hold stock or stock options. JK Moulder has received honorarium for consultancy from Hologic and Teleflex Medical. JF Carrillo is a consultant for AbbVie and is on the board of directors for the International Pelvic Pain Society. B Schneider is an employee of MyHealthTeams and received funding for conducting the research from AbbVie. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in the is work.

References

- 1.ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins‐Gynecology ACOG practice bulletin. Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(1):223–236. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuldeore MJ, Soliman AM. Prevalence and symptomatic burden of diagnosed endometriosis in the United States: national estimates from a cross-sectional survey of 59,411 women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2017;82(5):453–461. doi: 10.1159/000452660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Graaff AA, D’Hooghe TM, Dunselman GA, Dirksen CD, Hummelshoj L, Simoens S. The significant effect of endometriosis on physical, mental and social wellbeing: results from an international cross-sectional survey. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(10):2677–2685. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fourquet J, Gao X, Zavala D, et al. Patients’ report on how endometriosis affects health, work, and daily life. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(7):2424–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagervold B, Jenssen M, Hummelshoj L, Moen MH. Life after a diagnosis with endometriosis - a 15 years follow-up study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(8):914–919. doi: 10.1080/00016340903108308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shum LK, Bedaiwy MA, Allaire C, et al. Deep dyspareunia and sexual quality of life in women with endometriosis. Sex Med. 2018;6(3):224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2018.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pluchino N, Wenger JM, Petignat P, et al. Sexual function in endometriosis patients and their partners: effect of the disease and consequences of treatment. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(6):762–774. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmw031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denny E, Mann CH. Endometriosis-associated dyspareunia: the impact on women’s lives. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2007;33(3):189–193. doi: 10.1783/147118907781004831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Graaff AA, Van Lankveld J, Smits LJ, Van Beek JJ, Dunselman GA. Dyspareunia and depressive symptoms are associated with impaired sexual functioning in women with endometriosis, whereas sexual functioning in their male partners is not affected. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(11):2577–2586. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, Mitchell H, Denny E, Raine-Fenning N. A qualitative study of the impact of endometriosis on male partners. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(8):1667–1673. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Apers S, Dancet EAF, Aarts JWM, Kluivers KB, D’Hooghe TM, Nelen W. The association between experiences with patient-centred care and health-related quality of life in women with endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2018;36(2):197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2017.10.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson RL, Meana M. Early dyspareunia experience in young women: confusion, consequences, and help-seeking barriers. J Sex Med. 2011;8(3):814–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02150.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Lindau ST. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9(5):1285–1294. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.As-Sanie S, Black R, Giudice LC, et al. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(2):86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Briedite I, Ancane G, Ancans A, Erts R. Insufficient assessment of sexual dysfunction: a problem in gynecological practice. Medicina (Kaunas). 2013;49(7):315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shifren JL, Johannes CB, Monz BU, Russo PA, Bennett L, Rosen R. Help-seeking behavior of women with self-reported distressing sexual problems. J Womens Health. 2009;18(4):461–468. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadownik LA, Seal BN, Brotto LA. Provoked vestibulodynia: a qualitative exploration of women’s experiences. B C Med J. 2012;54:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorensen J, Bautista KE, Lamvu G, Feranec J. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual pain: a clinical review. Cureus. 2018;10(3):e2379. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vercellini P, Meana M, Hummelshoj L, Somigliana E, Vigano P, Fedele L. Priorities for endometriosis research: a proposed focus on deep dyspareunia. Reprod Sci. 2011;18(2):114–118. doi: 10.1177/1933719110382921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hummelshoj L, De Graaff A, Dunselman G, Vercellini P. Let’s talk about sex and endometriosis. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2014;40(1):8–10. doi: 10.1136/jfprhc-2012-100530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dargie E, Gilron I, Pukall CF. Provoked vestibulodynia. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(10):870–876. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pukall CF, Smith KB, Chamberlain SM. Provoked vestibulodynia. Women Health. 2007;3(5):583–592. doi: 10.2217/17455057.3.5.583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao C, Noga H, Allaire C, et al. Provoked vestibulodynia in women with pelvic pain. Sex Med. 2019;7(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seehusen DA, Baird DC, Bode DV. Dyspareunia in women. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(7):465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber JD, Pukall CF, Boyer SC, Reissing ED, Chamberlain SM. “Just relax”: physicians’ experiences with women who are difficult or impossible to examine gynecologically. J Sex Med. 2009;6(3):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hsu AL, Khachikyan I, Stratton P. Invasive and non-invasive methods for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53(2):413. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181db7ce8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schliep KC, Mumford SL, Peterson CM, et al. Pain typology and incident endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(10):2427–2438. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yong PJ. Deep dyspareunia in endometriosis: a proposed framework based on pain mechanisms and genito-pelvic pain penetration disorder. Sex Med Rev. 2017;5(4):495–507. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266–271. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vannuccini S, Lazzeri L, Orlandini C, et al. Mental health, pain symptoms and systemic comorbidities in women with endometriosis: a cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;39(4):315–320. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2017.1386171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klein S, D’Hooghe T, Meuleman C, Dirksen C, Dunselman G, Simoens S. What is the societal burden of endometriosis-associated symptoms? A prospective Belgian study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2014;28(1):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(2):366–373.e368. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.05.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Culley L, Law C, Hudson N, et al. The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women’s lives: a critical narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2013;19(6):625–639. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmt027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melis I, Litta P, Nappi L, Agus M, Melis GB, Angioni S. Sexual function in women with deep endometriosis: correlation with quality of life, intensity of pain, depression, anxiety, and body image. Int J Sex Health. 2015;27(2):175–185. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2014.952394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha S, Thakar R. Female sexual dysfunction. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;153(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heim LJ. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of dyspareunia. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(8):1535–1544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamvu G, Antunez-Flores O, Orady M, Schneider B. Path to diagnosis and women’s perspectives on the impact of endometriosis pain. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2020;12(1):16-25. doi: 10.1177/2284026520903214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yong PJ, Williams C, Bodmer-Roy S, et al. Prospective cohort of deep dyspareunia in an interdisciplinary setting. J Sex Med. 2018;15(12):1765–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nappi RE, Cucinella L. Advances in pharmacotherapy for treating female sexual dysfunction. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16(6):875–887. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1020791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leyland N, Taylor HS, Archer DF, et al. Elagolix reduced dyspareunia and improved health-related quality of life in premenopausal women with endometriosis-associated pain. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2284026519872401. [Google Scholar]

- 41.McDermid B. AbbVie prices new endometriosis drug at $10,000 a year. 2018. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-abbvie-orilissa/abbvie-prices-new-endometriosis-drug-at-10000-a-year-idUSKBN1KE2O3.

- 42.Fantasia HC. Treatment of dyspareunia secondary to vulvovaginal atrophy. Nurs Women Health. 2014;18(3):237–241. doi: 10.1111/1751-486X.12125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulligan K. Contraception use, abortions, and births: the effect of insurance mandates. Demography. 2015;52(4):1195–1217. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0412-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hekkert KD, Cihangir S, Kleefstra SM, van den Berg B, Kool RB. Patient satisfaction revisited: a multilevel approach. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(1):68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westaway MS, Rheeder P, Van Zyl DG, Seager JR. Interpersonal and organizational dimensions of patient satisfaction: the moderating effects of health status. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(4):337–344. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzg042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brotto LA, Yong P, Smith KB, Sadownik LA. Impact of a multidisciplinary vulvodynia program on sexual functioning and dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2015;12(1):238–247. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Duggan M, Brenner J. The Demographics of Social Media Users, 2012. Vol. 14 Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Graaff AA, Dirksen CD, Simoens S, et al. Quality of life outcomes in women with endometriosis are highly influenced by recruitment strategies. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(6):1331–1341. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Topolovec-Vranic J, Natarajan K. The use of social media in recruitment for medical research studies: a scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(11):e286. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheung KL, Ten Klooster PM, Smit C, de Vries H, Pieterse ME. The impact of non-response bias due to sampling in public health studies: a comparison of voluntary versus mandatory recruitment in a Dutch national survey on adolescent health. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):276. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4189-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saha R, Marions L, Tornvall P. Validity of self-reported endometriosis and endometriosis-related questions in a Swedish female twin cohort. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(1):174–178.e172. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]