Abstract

Most studies on survival sex, defined as sex trading for money, drugs, or other needs, have limited their focus to adolescents. The current study reports about the relationships between survival sex trading (SST) and high-risk behaviors in a sample of adults. Bivariate analysis shows that HIV-positive status, use of cocaine, ketamine, methamphetamine, heroin, having received drug treatment, and having received medical services are associated with SST. SST are more likely to not use condoms with partners other than their main partner, to have partners who inject drugs and are more likely to use drugs with sex. A logistic regression model included unwanted sexual touching, partner abuse, identifying as bisexual, African American, higher age, gender (women more likely), homelessness, higher number of sexual partners, having anal sex, injection drug use, HIV seropositivity, crack use, and likelihood of injecting drugs. The model was retested on independently collected Risk Behavior Assessment (RBA) data and showed significant relationships between survival sex and crack use, gender (women more likely), HIV positivity, identifying as bisexual, having anal sex, African American and higher number of sex partners. These findings make it imperative to integrate victimization counseling and HIV education into substance abuse treatment programs.

Keywords: survival sex, sex for drugs, crack use, homeless

Survival sex trading (SST) has been defined as the “exchange of sex for food, money, shelter, drugs, and other needs and wants” (Walls & Bell, 2011, p. 424). The emphasis is on trading sex to meet economic or subsistence needs (Greene, Ennett, & Ringwalt, 1999; Whyte, 2006). Reports of those who engage in SST have shown very high associations of SST with homelessness and marginalization by economic poverty, which leads to many reports of trading sex for shelter (Whyte, 2006). Those who engage in SST may also trade sex for food, drugs, or money (Greene et al., 1999). SST has also been correlated with the number of meals missed per week (MacLachlan et al., 2009). Having extremely restricted economic options may result in survivor sex traders’ sex work in dangerous circumstances (Stella, 2013). Note that the use of the term “survival sex” is a more specific term than “sex work.” Therefore, in the current study, we adopt the use of the term “survival sex” because it emphasizes the extreme need-driven sex that connotes a precarious economic aspect to the sex transaction (McMillan, Worth, & Rawstorne, 2018). This study seeks to examine a conceptual model that links SST to other relevant antecedents such as the characteristics and risk behaviors of adult sex traders in order to shed further light on this phenomenon in the literature.

Prevalence of SST

The prevalence of SST has been estimated from a nationally representative sample using a multistage sampling from both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas, which found that approximately 28% of street youths and 10% of shelter youths participated in survival sex (Greene et al., 1999). A study in Minnesota found that over 20% of homeless youths had a history of survival sex (Halcón & Lifson, 2004). A fact sheet by the Crimes Against Children Research Center concluded that “there is currently no reliable estimate of juvenile prostitution” (Stransky & Finkelhor, 2008, p. 5). There are, however, data on the number of juvenile arrests for prostitution in 2010 which was 1,000 (Sickmund & Puzzanchera, 2014). Unfortunately, there are few comparable data that shows SST prevalence among adult populations, meaning that when discussing SST in the U.S., the emphasis in the literature has been on juveniles and not adults.

Economic Factor - Homelessness

Homelessness seems to be a constant in samples of those who engage in survival sex. In a study of African American women in the US, there was a substantial level of sex out of fear of shelter loss or the loss of a place to live (Whyte, 2006). Those who had longer periods of homelessness had higher rates of engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors (Caccamo, Kachur, & Williams, 2017). Covenant House found that shelter was the number one commodity traded for sex, and that half of those who traded sex did so because they did not have a place to stay (Bigelsen & Vuotto, 2013). A study in Washington DC found that length of homelessness and number of homeless episodes increased the odds of engaging in survival sex (Purser, Mowbray, & O'Shields, 2017). In Hollywood, California, those who engaged in SST were desperate for a place to stay and food in addition to money (Warf et al., 2013).

History of Abuse

Survival sex trading (SST) is linked to abuse history, mainly sexual abuse (Stoltz et al., 2007). For instance, in a sample of homeless and runaway youth, having a history of sexual abuse was positively correlated with participating in SST (Tyler, Hoyt, Whitbeck, & Cauce, 2001). Not only are homeless and runaway youth more likely to have a history of sexual victimization, but they are more likely to continue to be victims of abuse because they find themselves in high-risk situations. Engaging in SST significantly increases their risk of being a victim of sexual assault (Tyler, Hoyt, Whitbeck, & Cauce, 2001; Tyler et al., 2001; Whitbeck, Chen, Hoyt, Tyler, & Johnson, 2004). A study in the Midwest US reported that survival sex exposed women to violence (Mallory & Stern, 2000) and there have been many reports of the disappearance and other victimization of drug-using survival sex workers (Shannon, Kerr, Allinott, et al., 2008). It appears that women who engaged in STT are more likely than those without a history of sex exchange to have been abused by someone other than a parent or an intimate partner (Logan, Cole, & Leukefeld, 2003).

History of Drug Use

Illicit substance use has been associated with survival sex in several studies. Crack use has been shown to have had a role in driving women into survival sex (Logan et al., 2003; Surratt, Inciardi, Weaver, & Falú, 2005). This may be because heavier crack use is associated with homelessness and those sex traders who were homeless performed more unprotected sex acts with paying partners who were more likely to refuse to use a condom (Edwards, Halpern, & Wechsberg, 2006; Surratt & Inciardi, 2004). A study of survival sex workers reported that sharing drugs, most often crack cocaine, with clients was associated with daily crack cocaine smoking, inconsistent condom use, and verbal, physical, or sexual assault (Shannon, Kerr, Bright, Gibson, & Tyndall, 2008). A study of crack-for-sex exchanges showed that those engaging in this practice had a higher number of clients, inconsistent condom use, and were more likely to be homeless (Duff et al., 2013). Women who use crack more frequently are more heavily involved in risky sexual behavior (Hoffman, Klein, Eber, & Crosby, 2000). Crack use appears to be a stronger predictor of multiple sexual partners and exchanging sex than injection drug use by itself (Booth, Kwiatkowski, & Chitwood, 2000). The sexual risk behavior has been shown to be significantly associated with higher HIV seropositivity among crack smoking sex workers in multisite studies (Edlin et al., 1994).

Demographic Characteristics

Age.

Past studies on survival sex trading have typically been limited to homeless and runaway youth (Marshall, Shannon, Kerr, Zhang, & Wood, 2010; Tyler et al., 2001; Walls, Potter, & Van Leeuwen, 2009). However, the findings on age are mixed in the literature. For instance, two studies reported that survival sex is more likely among younger participants (i.e., at least 18 years old in one case and at least 25 years old in the other (Marchand et al., 2012; Whyte, 2006). In a study comparing adults who traded sex as juveniles versus adult first-time sex traders, the researchers found that women who first traded sex as adults had been drug users prior to getting involved in sex trade (Martin, Hearst, & Widome, 2010). Those first-time adult sex traders (their median age was 22) were 3.44 times more likely to be drug users prior to trading sex and, therefore, their SST was initiated to support their drug use. Three studies reported that survival sex is more likely among older participants than among younger ones in their studies (Marshall et al., 2010; Walls & Bell, 2011; Whitbeck et al., 2004). To shed further light on the relationship between age and SST, the current study examines SST among adult respondents who received HIV prevention services throughout Los Angeles County.

Race.

Most U.S. studies report that those who engage in STT are more likely to be African American (Bobashev, Zule, Osilla, Kline, & Wechsberg, 2009). For example, when running six different models of data obtained on 1,600 participants from 28 states, researchers found that African Americans were significantly more likely than Whites to engage in STT (Walls & Bell, 2011).

Sex and sexual orientation.

Gay, lesbian and bisexuals were more likely to have engaged in SST compared to heterosexuals (Walls & Bell, 2011). Both women and men who sold sex in North Carolina were significantly more likely to be bisexual (Bobashev et al., 2009), and a Kentucky study also found that for both men and women, bisexuality was highly associated with sex trading (Logan & Leukefeld, 2000). A study of national data found that bisexuals were more likely to be involved in sex exchange (Logan & Leukefeld, 2000). A Canadian study found that heterosexual women were more likely than heterosexual men to engage in SST with an odds ratio over 4. However, sexual minority women had an odds ratio over 6 and sexual minority men had an odds ratio over 16 in comparing their odds of engaging in SST compared to heterosexual men (Marshall et al., 2010).

Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses

Conceptual framework.

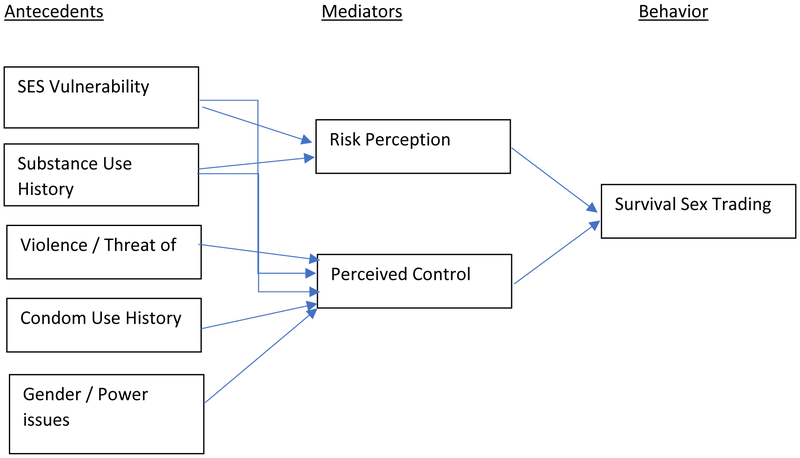

The broader literature of female sex workers and their risk behaviors consists of conceptual models such as the “Sexual Decision-Making among Female Sex Worker” framework (Bailey & Figueroa, 2016). Examining the sexual risk behavior of Jamaican sex workers, Bailey and Figueroa clustered socio-psychological factors that might explain the target behavior, such as socioeconomic vulnerability, cultural norms, gender and power issues, and attitudes towards men and sex, for instance.

Based on the review of research empirical evidence in the SST literature, and given that Bailey and Figueroa’s (2016) broad outcome of sexual risk behavior could be specified as SST, we adapted the researchers’ framework to further explain adults’ SST behavior, and we called our model the “Conceptual Framework of Survival Sex Trading as Predicted by Socio-psychological Factors.” As seen in Figure 1, we conceptualize that adults’ SST behavior may be predicted by their socioeconomic vulnerability (e.g., homelessness), their history of abuse and violence (e.g., sexual and physical), their history of drug use and condom use, as well as relevant gender and power issues. Those antecedents, by themselves or together, may increase sex traders’ frequency of risk behavior and/or reduce their sense of having some control over their own life. The more frequently those risky behaviors occur, the greater likelihood at-risk adults would engage in SST and would have lower perceived control.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework of survival sex trading behavior as predicted by socio-psychological factors

Hypotheses.

We conducted a study using two adult samples from Los Angeles County, CA, USA, that partially tested our conceptual framework, namely the relationships between SST antecedents and the target behavior. Additionally, we also examined the link between SST and a sexual risk consequence (i.e., HIV seropositive). Our hypotheses are thus as follows:

Those engaging in SST are more likely to use illicit drugs and more likely to inject illicit drugs than those who do not engage in SST.

Those engaging in SST are more likely to have experienced unwanted sexual touching and being slapped or hit.

Those engaging in SST are lower likelihood of condom use even though they will have more sexual partners.

Those engaging in SST are more likely to test HIV seropositive than those who do not.

Method

This study utilized the data of two adult samples: First, we tested part of our conceptual model using a subset of the 2004 Countywide Risk Assessment Survey (CRAS) dataset, developed and collected by the Los Angeles County’s Department of Public Health (DPH). The multivariate model developed using the CRAS data was then replicated and validated by using the Risk Behavior Assessment (RBA) data obtained from the Center for Behavioral Research and Services (CBRS) in Los Angeles County.

Countywide Risk Assessment Survey Data

Original data.

Los Angeles County Department of Public Health (DPH) conducts an annual risk assessment survey called the Countywide Risk Assessment Survey (CRAS) to better understand the HIV at-risk populations in the community and to identify key target populations for prioritization and allocation of DPH resources. The CRAS included items assessing SST and possible relevant factors, which were subsequently analyzed in the present study. (Those items will be described in a following section.) Although the CRAS is descriptive by nature, it consists of behavioral, biographical, and biological variables that could be used to explain a social and health phenomenon such as SST. It has been used in studies of the health of transgender clients (Edwards, Fisher, & Reynolds, 2007), heterosexual anal sex (Reynolds, Fisher, Napper, Fremming, & Jansen, 2010), and HIV service utilization (Fisher et al., 2010).

Data collection procedures.

In terms of data collection procedures, DPH first compiled a list of venues from across Los Angeles County where the target populations could be found. DPH then used stratified sampling to determine which venues would be included, resulting in 51 HIV/AIDS prevention subcontractors, and used simple random sampling to identify individuals from those venues to survey. Every nth person (either 2 if venue was small or 3 if venue was large based upon historical data that was not available in the dataset that LA County made available to us) was asked to respond to the survey, but some who were asked declined.

The data were collected in May and June of 2004 by stratified and systematic sampling. Of 2,520 surveys that were issued, 2,107 were completed by 238 staff members at various HIV/AIDS prevention and education public health sites throughout Los Angeles County, such as in drug treatment centers, HIV testing sites, medical facilities, community-based organizations, and prevention-outreach sites (Janson, Ogata, & Ayala, 2004). All interviewers completed a 6-hour training session prior to administering the surveys face-to-face. In order to be eligible for the survey a respondent had to be receiving HIV prevention services from a contractor funded by DPH. All parts of the study had prior approval by the Los Angeles County Institutional Review Board and the California State University, Long Beach Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Risk Behavior Assessment Data

Replication data.

The Center for Behavioral Research and Services (CBRS) was an HIV/STD testing site that also provided a foodbank for homeless and indigent clients, and HIV prevention counseling. It was located between two gang injunction areas in an extremely low-income area of Los Angeles County. All study participants signed an informed consent form that was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the California State University Long Beach. Even though CBRS was designed as a “one-stop shop” for social services that served Service Planning Area 8 (South bay) of Los Angeles County, all clients completed a Risk Behavior Assessment (RBA) at their initial visit.

Data collection procedures.

The RBA is a structured interview that has questions about demographics, drug use, injection drug use, recent drug use, drug abuse treatment, sexual behavior, sex trading, sexually transmitted infection history, arrest and incarceration, and economics.

Participants

CRAS participants.

As mentioned above, the present study analyzed a subset of data from the 2004 CRAS. First, because the study targeted adult populations, data from respondents who were under the age of 18 were deleted from the subsequent analysis. Secondly, only complete data points on the SST-related variables were retained, which left the total sample of N = 1,906 respondents in the present study.

The largest racial group of the sample was Hispanic (43%), followed by African American (28%), White (18%), and other racial groups (11%). The majority of the sample were males (67%). A majority of the sample was heterosexual (53%), followed by gay (29%), bisexual (15%), and lesbian/other (3%). The mean age of the sample was 33.34 (SD = 10.63) years, Median was 32, Mode was 20, and the age ranged from 18 to 69 years.

RBA participants.

The RBA data from CBRS was collected between 2000 and 2014. The sample included N = 7,905 non-duplicated cases. The largest racial group was Black-Not Hispanic at 42%, followed by White-Not Hispanic at 34%, and Hispanic at 23%, so the racial distribution differed from the CRAS. However, similar to the CRAS, a majority of the RBA sample was male (71%). A majority of the RBA sample was heterosexual at 62%, followed by gay at 21%, bisexual at 14%, and other at 3%. Mean age of the RBA sample was 39.35 (SD = 11.81) years, Median was 40, Mode was 44.

Measures

CRAS.

Most of the target variables were assessed with single, dichotomous items in CRAS. Survival sex trading was ascertained by the question “Have you ever gotten paid for sex with money, drugs, or something else you needed?” All types of drug use were obtained from the series of questions “Did you use [drug type] in the past six months?” The SES Vulnerability variable was assessed with the question “Where are you living or where did you sleep last night?” The Violence/Threat of Violence variables were ascertained with the questions “Did anyone sexually touch you when you did not want to be touched?” and “Has your partner or any of your partners ever slapped or hit you?” The anal sex variable was based on reports of having had receptive or penetrative anal sex within the last six months. These variables were coded as 0 for no and 1 for yes. All “decline to say” and “don’t know” responses were removed.

RBA.

The RBA was developed by the Community Research Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in collaboration with AIDS Cooperative Agreement program grantees. The RBA has been shown to have good reliability and validity of the drug use variables and HIV test variables (Dowling-Guyer, Johnson, Fisher, & Needle, 1994; Fisher, Reynolds, Jaffe, & Johnson, 2007), and good reliability of the sexual risk variables (Needle et al., 1995). The HIV report was captured by the question “Have you ever been told that you were infected with the AIDS virus (HIV)?” The crack question was “Have you ever used crack (smokable cocaine)?” The anal sex variable was a composite of having anal sex with men who only have sex with women combined with anal sex with men who have sex with both men and women. The question about the number of sex partners was “During the last 30 days, how many different people have you had vaginal, oral, and/or anal sex with?” The question about sexual orientation was “Do you consider yourself to be [list of options].”

Analysis Methods

Categorical variables were analyzed with Pearson Chi-square test of independence. A SAS macro was used to perform all pairwise comparisons of proportions (Elliott & Reisch, 2006). The macro transforms the proportions using an arcsin transformation and a standard error is also calculated. The resulting obtained values of the q statistic are then compared to qcrit.05. If qob>qcrit, the null hypothesis that the proportions are equal is rejected. Ordinal variables were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Continuous variables were analyzed with the student t-test assuming equal variances.

The multivariate logistic model was constructed using procedures from Hosmer, et al. (Hosmer, Lemeshow, & Sturdivant, 2013). The methods for the logistic regression models include both a plan for selecting variables and a method for assessing adequacy. Model building seeks to have the most parsimonious model that still reflects the outcome. Having a parsimonious model means that the model will be numerically stable, more easily adopted by others, and will have smaller standard errors.

The first step in the Hosmer et al. (2013) purposeful selection method of model building is to start with a careful univariable analysis of each candidate independent variable. Therefore, the top portions of Tables 1 and 2 show the Pearson Chi-square test results for the categorical variables (acceptable according to Hosmer et al.). The bottom of those two tables show the results of either the Wilcoxon two-sample test or the two-sample t-test for the continuous variables (also acceptable according to Hosmer et al.).

Table 1.

Demographic Differences Between Survival Sex Traders and non-Traders

| Variable | Survival Sex Traders (n=485) |

Non-Traders (n=1421) |

χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | n(%) | n(%) | |||

| Whitecd | 92(19) | 247(17) | |||

| African Americanabc | 194(40) | 333(23) | |||

| Hispanicad | 155(32) | 667(47) | |||

| Otherb | 44(9) | 174(12) | 58.4 | 3 | .0001 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 302(62) | 976(67) | |||

| Female | 185(38) | 445(31) | 7.3 | 1 | .0069 |

| Sexual Orientation | |||||

| Heterosexuala | 222(46) | 795(56) | |||

| Gayb | 141(29) | 403(28) | |||

| Bisexualab | 103(21) | 178(13) | |||

| Lesbian/Other | 21(4) | 45(3) | 27.04 | 3 | .0001 |

| Living Arrangements | |||||

| House/Apartmentabcde | 225(46) | 1101(78) | |||

| Hotel, Motelb | 31(6) | 33(2) | |||

| Halfway housec | 120(25) | 145(10) | |||

| Shelter/Missione | 30(6) | 47(3) | |||

| Street, Sidewalk, Alley, Parkd | 50(10) | 64(5) | |||

| Othera | 30(6) | 28(2) | 171.6 | 5 | .0001 |

| M(SD) | M(SD) | Z/t | df | p | |

| Educationa | 2.7(1.48) | 3.2(1.65) | 5.87b | .0001 | |

| Age in years | 35.8(9.47) | 32.6(10.90) | 5.81 | 1906 | .0001 |

Note. Groups that have subscripts with the same letter are significantly different at p<.05.

Scale is 1=Did not get high school diploma or GED, 2=GED, 3=High school diploma, 4=1-2 years of college or vocational school, 5=3 or more years of college but no degree, 6=4-year college degree, 7=Graduate or Professional school.

Z for Wilcoxon two-sample test.

Table 2.

Behavioral Differences Between Those Who Sex Traded and Those Who Did Not

| Survival Sex traders (n = 489) n(%) |

Did not sex trade (n=1509) n(%) |

x2 | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted sexual touching | 323(66) | 366(26) | 258.73 | 1 | <.001 |

| Slapped or hit by partner | 291(60) | 359(25) | 192.08 | 1 | <.001 |

| Crack use (past six months) | 179(37) | 184(13) | 134.44 | 1 | <.001 |

| Receiving drug treatment (past six months) | 219(45) | 294(21) | 109.21 | 1 | <.001 |

| Injection drug use | 197(41) | 253(18) | 105.61 | 1 | <.001 |

| Likelihood of shooting drugs in the next six months | 79(16) | 74(5) | 59.58 | 1 | <.001 |

| Methamphetamine use (past six months) | 147(30) | 203(14) | 61.09 | 1 | <.001 |

| Heroin use (past six months) | 98(20) | 122(9) | 47.25 | 1 | <.001 |

| Receiving medical treatment (past six months) | 267(55) | 535(38) | 44.27 | 1 | <.001 |

| HIV-positive status | 130(34) | 194(18) | 40.38 | 1 | <.001 |

| Powdered cocaine use (past six months) | 95(20) | 152(11) | 25.46 | 1 | <.001 |

| Anal sex (past six months) | 247(51) | 565(40) | 17.82 | 1 | <.001 |

| Giving oral sex (past six months) | 356(73) | 909(64) | 13.54 | 1 | <.001 |

| Receiving oral sex (past six months) | 356(73) | 943(66) | 758 | 1 | <.006 |

| Ketamine use (past six months) | 15(3) | 18(1) | 7.01 | 1 | .008 |

| Vaginal sex (past six months) | 257(53) | 709(50) | 1.20 | 1 | .27 |

| Variable | M(SD) | M(SD) | Z/t | df | p |

| Number of Sex Partners (past six months) | 11.0(34.28) | 2.7(11.79) | 7.87 | 1906 | .0001 |

| Use a condom for vaginal sexa | 1.5 (0.73) | 1.7 (0.76) | 2.57b | .0101 | |

| Use condom, dental dam or other barrier for oral sexa | 1.3 (0.60) | 1.3 (0.59) | 1.15b | .2501 | |

| Use condom for anal sexa | 1.7 (0.78) | 1.9 (0.85) | 1.31b | .1907 |

Scale is 1=Never, 2=Sometimes, 3=Always.

Z for Wilcoxon two-sample test.

Step 2 involves fitting the multivariate model and eliminating variables that do not contribute to the model. Step 3 involves adding back to the model any variables that were eliminated in Step 2 but subsequently found to be important because they provide a needed adjustment of those variables that remain in the model. Step 4 is to continue this process of adding and taking out variables until there is a preliminary main effects model.

Step 5 is to check assumptions and to make sure that continuous variables are linear in the logit. This step results in the main effects model. Step 6 is to check for interactions because an interaction implies that the effect of each variable is not constant over the levels of the other variable. This step results in the preliminary final model. Step 7 is to check the model fit using methods such as the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit method (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1980).

The RBA replication model selected variables from the RBA that were analogous to those included in the CRAS multivariate logistic regression model. There were some CRAS variables that had no RBA analogue so were not considered. Some of the analogous variables were not selected for the RBA multivariate model because they were not significant when they were included. This model only kept those analogues that were significant. This is discussed further in the results section below.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

In terms of the prevalence of SST, 25% (n = 485) of the respondents identified themselves as engaging in SST (i.e., reporting that they had traded sex for money, drugs, or anything else they needed). From Table 1, although African Americans were not the largest racial group in the sample, they were significantly different from the other three ethnicities in that African Americans were the most likely to engage in survival sex. Those who were living in a halfway house, treatment center, or sober living facility were significantly more likely to report survival sex trading, and those who were living in a house or apartment were significantly less likely to report survival sex trading. Table 1 also shows that the survival sex traders were significantly older than the non-traders. Those who have a history of survival sex trading also have lower educational levels, with 32% of the survival sex traders reporting they did not receive a high school diploma or get a GED.

In the replication data (RBA) presented in Table 4, the prevalence of SST was 26%, which means n = 2021 identified themselves as engaging in trading sex for money, sex for drugs, or both. The finding for African Americans being more likely to engage in SST was confirmed.

Table 4.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model of Survival Sex Trading for Risk Behavior Assessment Data

| Predictor | B | SE | Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result of HIV test positive | 1.00 | .15 | 2.74 | 2.05, 3.66 |

| Crack use | 2.01 | .07 | 8.05 | 6.99, 9.27 |

| Female | 1.38. | .07 | 3.96 | 3.45, 4.55 |

| Anal sex (past 30 days) | .57 | .08 | 1.77 | 1.50, 2.08 |

| Number of sex partners (past 30 days) for five partners | .15 | .01 | 1.16 | 1.13, 1.19 |

| Ethnicity (White reference) | ||||

| African American | .36 | .04 | 1.44 | 1.25, 1.64 |

| Hispanic | −0.37 | .05 | 0.69 | 0.58, 0.83 |

| Sexual Orientation (Heterosexual reference) | ||||

| Homosexual | −.09 | .08 | 1.13 | 1.06, 1.60 |

| Bisexual | .67 | .07 | 2.80 | 2.36, 3.32 |

| Lesbian/other | −.22 | .13 | 1.15 | 0.83, 1.61 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Test: χ2 = 33.42, df = 8, p = .001. McFadden’s R-Square = .2516

Hypothesis Testing

We followed Hosmer et al.’s (2013) seven steps of developing a multivariate logistic model and we developed the model presented in Table 3. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test is presented to assess goodness of fit (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1980). For assessing predictive power, Table 3 presents the McFadden R2 measure (McFadden, 1974) which is the only one that is recommended (D. Hosmer, personal communication, May 2, 2019).

Table 3.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model of Survival Sex Trading for COUNTYWIDE RISK ASSESSMENT SURVEY Data

| Predictor | B | SE | Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unwanted sexual touching | 1.36 | .17 | 4.07 | 3.06, 5.42 |

| Likelihood of shooting drugs in the next six months | 1.08 | .31 | 2.38 | 1.42, 4.00 |

| Partner ever slapped or hit you | .47 | .16 | 1.95 | 1.47, 2.57 |

| Result of HIV test positive | .59 | .18 | 1.81 | 1.23, 2.59 |

| Crack use | 53 | 18 | 1.76 | 1.29, 2.42 |

| Female | .80 | .19 | 1.76 | 1.26, 2.46 |

| Ever Injected drugs | .54 | .19 | 1.63 | 1.14, 2.31 |

| Anal sex (past six months) | .48 | .18 | 1.41 | 1.03, 1.91 |

| Number of sex partners (past six months) for five partners | .02 | .01 | 1.15 | 1.08, 1.22 |

| Age in years for five years | .01 | .01 | 1.10 | 1.03, 1.17 |

| Ethnicity (White reference) | ||||

| African American | .69 | .13 | 2.11 | 1.44, 3.11 |

| Hispanic | −0.28 | .13 | 0.76 | 0.52, 1.11 |

| Other | −0.33 | 0.19 | 0.78 | 0.47, 1.31 |

| Sexual Orientation (Heterosexual reference) | ||||

| Homosexual | .23 | .18 | 2.19 | 1.46, 3.28 |

| Bisexual | .24 | .18 | 2.08 | 1.39, 3.09 |

| Lesbian/other | -.14 | .32 | 1.52 | 0.77, 2.99 |

| Living arrangements (Apartment/house ref) | ||||

| Other | .58 | .32 | 3.61 | 1.85, 7.04 |

| Shelter or mission | .22 | .25 | 2.80 | 1.58, 4.98 |

| Treatment center, sober living, halfway house or care facility | .11 | .18 | 2.48 | 1.72, 3.57 |

| Hotel, motel, or rooming house | −.13 | .31 | 2.31 | 1.21, 4.40 |

| Street, Alley, Sidewalk, Park | −.20 | .27 | 2.24 | 1.32, 3.78 |

| Highest grade in school completed | −.17 | .05 | 0.84 | 0.76, 0.93 |

Hosmer and Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Test: χ2 = 3.96, df = 8, p = .86. McFadden’s R-Square = .2804

The behavioral associations shown in Table 2, can be grouped into several topics. One topic is the items indicating sexual abuse which were the largest effects in this table. Both unwanted touching and having been slapped or hit by a partner were significantly more likely in the survival sex traders. The drug use variables show that use of crack, methamphetamine, powdered cocaine, and ketamine to be more likely in the survival sex traders. Additionally, both reporting previous illicit drug injecting and intention to inject drugs were also significantly associated, along with having received drug treatment. The survival sex traders were significantly more likely to report having had anal sex, oral sex (both giving and receiving), but not vaginal sex, and to have significantly more sex partners in the last six months. Those who reported that they were positive for HIV and those who received drug treatment or medical services in the last six months were also more likely to have a history of survival sex trading.

Variables that were significant bivariately were included as candidates in constructing the logistic regression model which included twelve covariates, as shown in Table 3. Our multivariate model shows the largest odds ratio of having a history of being sexually touched when you did not want to be. The related item of having a partner slapping or hitting was also in the logistic model. These findings indicate that a history of being a victim of abuse is associated with survival sex trading. Including HIV positivity is also important in the model. Additionally, the crack use, ever injected, and intent to inject show the association of survival sex with illicit drug use. In order to understand the injection drug use better, we ran correlations of the injection variables with the drug variables. Both of the injection variables (ever-injected correlations are reported here, as the intent-to-inject correlations were similar so are not reported) are related to heroin, r(480)=.54 p<.0001, heroin and cocaine mixed together in a speedball, r(480)=.45 p<.0001, other opiate by itself, r(480)=.27 p<.0001, and crystal meth, r(480)=.19 p<.0001. The living situation design variable illustrates that living in a house or apartment is an important protective factor. The logistic regression model included anal sex, indicating that sex traders participate in riskier types of sex. The anal sex is associated with male participants and not the female participants who engaged in survival sex, χ2(1, N=489) = 42.18, p<.0001. In addition, the anal sex that the participants reporting survival sex is receptive and not insertive anal sex χ2(1, N=1996) = 22.35, p<.0001. However, even for women, those who reported survival sex are significantly more likely to have receptive anal sex χ2(1, N=1319) = 19.38, p<.0001. The odds ratios for both the age in years and the number of sex partners are reported for every five years or partners. The only protective factor was highest grade in school which indicates that the more school a respondent had, the less likely they were to engage in survival sex. In summary, the hypotheses were partially supported overall.

Table 5 shows a comparison of the logistic regression model using the CRAS data compared to the RBA data. The CRAS abuse variables did not have an analogue in the RBA data which was also true for the likelihood of drug injection. The drug injection, age, living arrangements, and education did have analogous variables in the RBA data however, these were not retained in the RBA logistic regression model. There were seven variables that replicated from the CRAS to the RBA data. Crack use and being female were much more important in the RBA data than they were in the CRAS data. Being HIV positive and reporting bisexual or homosexual orientation replicated. The sex risk behaviors of number of sexual partners, and anal sex also replicated.

Table 5.

Comparison Between Countywide Risk Assessment Survey Model and Risk Behavior Assessment Model

| Predictor | CRAS | RBA |

|---|---|---|

| Unwanted Sexual Touching | Present | No analogous variable |

| Likelihood of shooting drugs | Present | No analogous variable |

| Partner ever slapped or hit you | Present | No analogous variable |

| Result of HIV test positive | Present | Present |

| Crack Use | Present | Present |

| Female | Present | Present |

| Ever inject drugs | Present | Not selected for inclusion |

| Anal sex | Present | Present |

| Number of sex partners | Present | Present |

| Age in years | Present | No selected for inclusion |

| Ethnicity (White Reference) | Present | Present |

| Sexual Orientation (Hetero. Ref.) | Present | Present |

| Living arrangements | Present | Not selected for inclusion |

| Highest grade in school completed | Present | Not selected for inclusion |

Discussion

This study examined those who trade sex for the necessities of life and contributes to the literature by focusing on survival sex trading in adults, when most of the extant literature on this topic is with adolescents. The group of individuals in the current study who engaged in survival sex trading had a median age of 36 and the mode was 41. The RBA sample was somewhat older and had a median age of 40 and a mode of 44. This illustrates that both of our samples were adults which is different than a lot of the samples in most of the literature. Those who are Black in both datasets were more likely to engage in survival sex. This finding holds up in both the bivariate and the multivariate logistic model in which African Americans had a significant odds ratio of 2.11 compared to the White reference group and none of the other ethnicities were significant. In the RBA logistic regression model African American was also significant as a risk factor, however, Hispanic was a protective factor, meaning that Hispanics were less likely to engage in SST in the RBA dataset. A Colorado study found that African Americans in their sample were 1.5 or 2.5 times as likely (depending upon the model) to engage in survival sex compared to Whites (Walls & Bell, 2011) . Our value of 2.11 would be consistent with these previous findings. There has been a major health disparity in the U.S. in that Black women have disproportionately higher rates of HIV compared to women of other races (Bradley, Geter, Lima, Sutton, & Hubbard McCree, 2018). The lifetime risk for Black women was 1 in 54, for Hispanic/Latina women it was 1 in 256, and for White women it was 1 in 941 (Hess, Hu, Lansky, Mermin, & Hall, 2017). We are not able to determine to what extent survival sex is a contributing factor, but that may be an area for future study.

Among our sample, those who engaged in survival sex had significantly lower education levels than those who did not engage in survival sex. A Canadian study found that women who had fewer years of education were more likely to be sex workers (Marchand et al., 2012). This lack of education may reflect a lower chance of gainful employment, thus necessitating engaging in survival sex. This seems to be supported by a New York study that concluded that educational deficit was a main factor leading to participation in the street economy which includes survival sex (Gwadz et al., 2009).

The association between history of physical and/or sexual abuse and subsequent survival sex is well documented in the literature (Shannon, Kerr, Allinott, et al., 2008; Stoltz et al., 2007; Warf et al., 2013; Wechsberg et al., 2003; Whitbeck et al., 2004) and that those engaging in STT were more likely to have been abused by someone other than a parent or intimate partner (Logan et al., 2003). The current study’s findings suggest that adults who have been victimized are more likely to engage in survival sex trade. Similar results have been found with runaway youth. In our study of mostly adults, unwanted sexual touching and partner slapping or hitting abuse were significant as demonstrated by both the bivariate and the multivariate logistic regression model. The highest odds ratio in our logistic model was unwanted sexual touching at 4.07, and the third highest was partner abuse (has partner ever slapped or hit you) at 1.95.

In addition, drug use appears to be a major motivating factor for survival sex trading. Crack use was replicated in both datasets and was especially important in the RBA dataset. This seems reasonable given the correlation between having a history of victimization and drug use (Brems, Johnson, Neal, & Freemon, 2004). We suggest that once someone becomes a victim of sexual or physical abuse, they are then more likely to use drugs, and eventually to engage in sex trading. Our bivariate results included eight drug abuse-related variables, including the likelihood of injecting drugs in the next six months which also was the second highest odds ratio in our logistic model at 2.38. Our CRAS logistic regression model also included crack use and a lifetime history of injection drug use. In the RBA logistic regression model crack use had an odds ratio over 8 which is the largest odds ratio in either logistic regression model. The programmatic implications are to emphasize the importance of identifying victims of any kind of abuse early, so they get the help they need. A report from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Clinical Trials Network (CTN) highlighted the need for integrating sexual prevention interventions with substance abuse treatment (Tross et al., 2009).The current findings strongly corroborate the CTN conclusions. Given that receiving drug treatment in the past six months was significantly more likely for those who reported engaging in survival sex, it is not clear how much opportunity there was to deal with these issues in the drug treatment these individuals received. Frequent, and improved interventions would allow for advocating for victims of abuse to seek help from substance abuse treatment programs or from other available resources.

Those who engage in survival sex appear to be having a variety of sexual experiences including oral sex, vaginal sex, and anal sex. Our findings were consistent with a previous report that found an interaction between gender and sexual orientation in being associated with survival sex (Whitbeck et al., 2004). Anal sex was significant both in the bivariate analysis and in the logistic regression model and was replicated in the RBA data model. In addition, we showed that even though most of the anal sex reported by those reporting survival sex in our sample was by men, among women there was a strong association between survival sex and receptive anal sex. Anal intercourse has been shown repeatedly to be a very high risk behavior for HIV transmission with a 40% per partner transmission rate with no significant difference between heterosexuals and MSM (Baggaley, White, & Boily, 2010). For heterosexual women 28% of infections were associated with anal sex (O'Leary et al., 2017).

Strengths and Limitations

This study has many advantages, including a rigorous sampling plan and a large sample size taken from multiple sites throughout Los Angeles County. This study also was able to assess many of the characteristics of survival sex traders such as drug use, condom use, demographics, and services received. Another advantage of this study is the replication of the findings of half of the variables with a second dataset.

A limitation is that the question that was used to assess survival sex trading could have been more precise. The lack of specificity means that we were not able to distinguish how much of the sex trading was for money, how much for drugs, and how much for other survival needs. We were also not able to address sex trafficking, and the extent to which initiation into sex work was coerced. Age of first use of the different drugs, age of first coitus, and age of first trading sex would have been very helpful in establishing the logic of causal order so that mediational models could have had a theoretical basis.

Another limitation was the lack of information about loneliness. Loneliness may be related to unprotected anal intercourse among gay men (Martin & Knox, 1997). Among women loneliness has been reported to be related to both lifetime sex trading and past 90 day sex trading (Golder & Logan, 2007). A model from Spain found support for violence to lead to loneliness which in turn led to both lower physical health and drug use (Gonzalez, Picos, & De la Iglesia Gutierrez, 2018; Picos, Gonzalez, & de la Iglesia Gutierrez, 2018). If we had collected information on loneliness, we would have been able to test whether loneliness mediates between unwanted sexual touching and partner abuse as precursors and use of illicit drugs as a consequence. Future research should obtain more precise information to allow these distinctions to be made.

Future Direction

Due to the exploratory nature of the CRAS data set (as well as the replication data), we were able to detect the links between SST and other risk behaviors or sex traders’ characteristics. Future researchers should extend the literature by investigating the socio-psychological factors underlying survival sex traders’ decision to engage in that behavior beyond their characteristics or economic situations. In other words, future studies should focus on building a theoretical model that explains why certain factors would predict SST behavior while others would not. For instance, psychological variables such as perception of risk and perceived control might mediate the predicting effect of high-risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, condom use, abuse/violence) and of socioeconomic vulnerability onto SST.

Conclusion

Survival sex trading is a tragic path that some people take to obtain the necessities of life. Painful life experiences associated with drug, sexual, and physical abuse, along with a low level of educational attainment, and minimal opportunities for gainful legal employment influence the lives of these sex traders so that they could feel trapped in a world that only sees them as commodities. To transition to a better life, they have to overcome both psychological, economic and social inequalities. Sexual trauma counseling paired with vocational rehabilitation offered in substance abuse treatment programs could be an effective beginning for that transition.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by:

Award Number R01DA030234 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Award Number P20MD003942 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. This research was also funded, in part, by the City of Long Beach, California Department of Health and Human Services contract 28569, and Los Angeles County, California, Office of AIDS Programs and Policy contracts 700938 and 700939.

Contributor Information

Sarah E. Clingan, San Diego State University/University of California San Diego, Joint Doctoral Program, Interdisciplinary Research on Substance Use, San Diego, CA, USA

Dennis G. Fisher, Center for Behavioral Research and Services, and Psychology Department, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA

Grace L. Reynolds, Center for Behavioral Research and Services, and Department of Health Care Administration, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA

Michael A. Janson, Division of HIV and STD Programs, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Debra A. Rannalli, School of Nursing, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA

Loucine Huckabay, School of Nursing, California State University, Long Beach, CA, USA

Hannah-Hanh D. Nguyen, Shidler College of Business, University of Hawai'i at Manoa

References

- Baggaley RF, White RG, & Boily MC (2010). HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 1048–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A, & Figueroa JP (2016). A Framework for Sexual Decision-Making Among Female Sex Workers in Jamaica. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 911–921. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0449-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelsen J, & Vuotto S (2013). Homelessness, survival sex and human trafficking: As experienced by the youth of Covenant House New York. Retrieved from New York: https://humantraffickinghotline.org [Google Scholar]

- Bobashev GV, Zule WA, Osilla KC, Kline TL, & Wechsberg WM (2009). Transactional sex among men and women in the south at high risk for HIV and other STIs. Journal of Urban Health, 32–47. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9368-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, & Chitwood DD (2000). Sex related HIV risk behaviors: differential risks among injection drug users, crack smokers, and injection drug users who smoke crack. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58, 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley ELP, Geter A, Lima AC, Sutton MY, & Hubbard McCree D (2018). Effectively addressing Human Immunodeficiency Virus disparities affecting US Black women. Health Equity, 2, 329–333. doi: 10.1089/heq.2018.0038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brems C, Johnson ME, Neal D, & Freemon M (2004). Childhood abuse history and substance use among men and women receiving detoxification services. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 30, 799–821. doi: 10.1081/ada-200037546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caccamo A, Kachur R, & Williams SP (2017). Narrative review: Sexually transmitted diseases and homeless youth-What do we know about sexually transmitted disease prevalence and risk? Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 44, 466–476. doi: 10.1097/olq.0000000000000633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling-Guyer S, Johnson ME, Fisher DG, & Needle R (1994). Reliability of drug users’ self-reported HIV risk behaviors and validity of self-reported recent drug use. Assessment, 1, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- Duff P, Tyndall MW, Buxton J, Zhang R, Kerr T, & Shannon K (2013). Sex-for-crack exchanges: Associations with risky sexual and drug use niches in an urban Canadian city. Harm Reduction Journal, 10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlin BR, Irwin KL, Faruque S, McCoy CB, Word C, Serrano Y, . . . Holmberg SD (1994). Intersecting epidemics--crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. Multicenter Crack Cocaine and HIV Infection Study Team. New England Journal of Medicine, 331, 1422–1427. doi: 10.1056/nejm199411243312106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JM, Halpern CT, & Wechsberg WM (2006). Correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among women who use crack cocaine. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18, 420–429. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JW, Fisher DG, & Reynolds GL (2007). Male-to-female transgender and transsexual clients of HIV service programs in Los Angeles County, California. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1030–1033. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2006.097717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott AC, & Reisch JS (2006). Implementing a multiple comparison test for proportions in a 2xc crosstabulation in SAS. Paper presented at the Thirty-first Annual SAS Users Group International Conference, San Francisco, CA https://support.sas.com/resources/papers/proceedings/proceedings/sugi31/toc.html#st [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Jaffe A, & Johnson ME (2007). Reliability, sensitivity and specificity of self-report of HIV test results. AIDS Care, 19, 692–696. doi: 10.1080/09540120601087004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DG, Wishart D, Reynolds GL, Edwards JW, Kochems LM, & Janson MA (2010). HIV services utilization in Los Angeles County, California. AIDS and Behavior, 14, 440–447. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9500-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golder S, & Logan TK (2007). Correlates and predictors of women’s sex trading over time among a sample of out-of-treatment drugs abusers. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 628–640. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9158-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez RP, Picos AP, & De la Iglesia Gutierrez M (2018). “Surviving the violence, humiliation, and loneliness means getting high”; Violence, lonelines, and health of female sex workers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–22. doi: 10.1177/0886260518789904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene JM, Ennett ST, & Ringwalt CL (1999). Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. American Journal of Public Health, 89, 1406–1409. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwadz MV, Gostnell K, Smolenski C, Willis B, Nish D, Nolan TC, . . . Ritchie AS (2009). The initiation of homeless youth into the street economy. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 357–377. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halcón LL, & Lifson AR (2004). Prevalence and Predictors of Sexual Risks Among Homeless Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 33, 71–80. doi: 10.1023/A:1027338514930 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, & Hall HI (2017). Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 27, 238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JA, Klein H, Eber M, & Crosby H (2000). Frequency and intensity of crack use as predictors of women’s involvement in HIV-related sexual risk behaviors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW Jr., & Lemeshow S (1980). A goodness-of-fit test for the multiple logistic regression model. Communications in Statistics, A10, 1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW Jr., Lemeshow S, & Sturdivant RX (2013). Applied logistic regression (Third ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Janson MA, Ogata PC, & Ayala A (2004). Continued risk-taking among men who have sex with men living with HIV/AIDS in Los Angeles County. Paper presented at the The 132nd Annual Meeting of the American Public Health Association, Washington, DC https://apha.confex.com/apha/132am/techprogram/paper_81249.htm [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, Cole J, & Leukefeld C (2003). Gender differences in the context of sex exchange among individuals with a history of crack use. AIDS Education and Prevention, 15, 448–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan TK, & Leukefeld C (2000). HIV risk behavior among bisexual and heterosexual drug users. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 32, 239–248. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLachlan E, Neema S, Luyirika E, Ssali F, Juncker M, Rwabukwali C, . . . Duncan T (2009). Women, economic hardship and the path of survival: HIV/AIDS risk behavior among women receiving HIV/AIDS treatment in Uganda AIDS Care, 21, 355–367. doi: 10.1080/09540120802184121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory C, & Stern PN (2000). Awakening as a change process among women at risk for HIV who engage in survival sex. Qualitative Health Research, 10, 581–594. doi: 10.1177/104973200129118660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchand K, Oviedo-Joekes E, Guh D, Marsh DC, Brissette S, & Schechter MT (2012). Sex work involvement among women with long-term opioid injection drug dependence who enter opioid agonist treatment. Harm Reduction Journal, 9, 1–7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall BDL, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, & Wood E (2010). Survival sex work and increased HIV risk among sexual minority street-involved youth. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53, 661–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JI, & Knox J (1997). Loneliness and sexual risk behavior in gay men. Psychological Reports, 81, 815–825. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.81.3.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin L, Hearst MO, & Widome R (2010). Meaningful differences: Comparison of adult women who first traded sex as a juvenile versus as an adult. Violence Against Women, 16, 1252–1269. doi: 10.1177/1077801210386771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D (1974). Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior In P. Zaremka (Ed.), Frontiers in econometrics (pp. 105–142). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan K, Worth H, & Rawstorne P (2018). Usage of the terms Prostitution, Sex Work, Transactional Sex, and Survival Sex: Their utility in HIV prevention research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1517–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-1140-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, . . . Braunstein M (1995). Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 9, 242–250. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.9.4.242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary A, DiNenno E, Honeycutt A, Allaire B, Neuwahl S, Hicks K, & Sansom S (2017). Contribution of anal sex to HIV prevalence among heterosexuals: A modeling analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 21(10), 2895–2903. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1635-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picos AP, Gonzalez RP, & de la Iglesia Gutierrez M (2018). Exploring causes and consequences of sex workers’ psychological health: Implications for health care policy. A study conducted in Spain. Health Care for Women International, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2018.1452928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser GL, Mowbray OP, & O'Shields J (2017). The relationship between length and number of homeless episodes and engagement in survival sex. Journal of Social Service Research, 43, 262–269. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2017.1282393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds GL, Fisher DG, Napper LE, Fremming BW, & Jansen MA (2010). Heterosexual anal sex reported by women receiving HIV prevention services in Los Angeles County Women’s Health Issues, 20, 414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, & Tyndall MW (2008). Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 911–921. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K, Kerr T, Bright V, Gibson K, & Tyndall MW (2008). Drug sharing with clients as a risk marker for increased violence and sexual and drug-related harms among survival sex workers. AIDS Care, 20, 228–234. doi: 10.1080/09540120701561270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmund M, & Puzzanchera C (2014). Juvenile offenders and victims: 2014 national report. Retrieved from Pittsburgh, PA: https://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/nr2014/downloads/nr2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Stella. (2013). Language matters: Talking about sex work In Infosheet (pp. 1–4). Montreal QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Stoltz J-AM, Shannon K, Kerr T, Zhang R, Montaner JS, & Wood E (2007). Associations between childhood maltreatment and sex work in a cohort of drug-using youth. Social Science and Medicine, 65, 1214–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stransky M, & Finkelhor D (2008). How many juveniles are involved in prostitution in the U.S.? Fact Sheet. Retrieved from www.unh.edu/ccrc/prostitution/juvenile_Prostitution_factsheet.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, & Inciardi JA (2004). HIV risk, seropositivity and predictors of infection among homeless and non-homeless women sex workers in Miami, Florida, USA. AIDS Care, 16, 594–604. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001716397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, Inciardi JA, Weaver JC, & Falú VM (2005). Emerging linkages between substance abuse and HIV infection in St Croix, US Virgin Islands. AIDS Care, 17, S26–S35. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tross S, Hanner J, Hu M-C, Pavlicova M, Campbell A, & Nunes EV (2009). Substance use and high risk sexual behaviors among women in psychosocial outpatient and methadone maintenance treatment programs. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 35, 368–374. doi: 10.1080/00952990903108256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, & Cauce AM (2001). The effects of a high-risk environment on the sexual victimization of homeless and runaway youth. Violence and Victims, 16, 441–455. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.16.4.441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler KA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB, & Cauce AM (2001). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on later sexual victimization among runaway youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence 11, 151–176. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, & Bell S (2011). Correlates of engaging in survival sex among homeless youth and young adults. Journal of Sex Research, 48, 423–436. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2010.501916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls NE, Potter C, & Van Leeuwen J (2009). Where risks and protective factors operate differently: Homeless sexual minority youth and suicide attempts. Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal, 26, 235–257. doi: 10.1007/s10560-009-0172-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warf CW, Clark LF, Desai M, Rabinovitz SJ, Agahi G, Calvo R, & Hoffmann J (2013). Coming of age on the streets: Survival sex among homeless young women in Hollywood. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 1205–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WKK, Zule W, Hall G, Middlesteadt R, & Edwards J (2003). Violence, homelessness, and HIV risk among crack-using African-American women. Substance Use and Misuse, 38, 669–700. doi: 10.1081/JA-120017389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Chen X, Hoyt DR, Tyler KA, & Johnson KD (2004). Mental disorder, subsistence strategies, and victimization among gay, lesbian, and bisexual homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 329–342. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte J (2006). Sexual assertiveness in low-income African American women: unwanted sex, survival, and HIV risk. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 23, 235–244. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2304_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]