Abstract

Background

Since the start of the new Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in December 2019, pharmacists worldwide are playing a key role adopting innovative strategies to minimize the adverse impact of the pandemic.

Objectives

To identify and describe core services provided by the pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A literature search was performed in MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, and LILACS for studies published between December 1st, 2019 and May 20th, 2020 without language restriction. Studies that reported services provided by pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. Two independent authors performed study selection and data extraction with a consensus process. The pharmacist's intervention identified in the included studies were described based on key domains in the DEPICT v.2.

Results

A total of 1189 records were identified, of which 11 studies fully met the eligibility criteria. Most of them were conducted in the United States of America (n = 4) and China (n = 4). The most common type of publication were letters (n = 4) describing the workplace of the pharmacist in hospitals (n = 8). These findings showed the different roles of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as disease prevention and infection control, adequate storage and drug supply, patient care and support for healthcare professionals. Pharmacists' interventions were mostly conducted for healthcare professionals and patients (n = 7), through one-to-one contact (n = 11), telephone (n = 6) or video conference (n = 5). The pharmacists' main responsibility was to provide drug information for healthcare professionals (n = 7) as well as patient counseling (n = 8).

Conclusions

A reasonable number of studies that described the role of the pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic were found. All studies reported actions taken by pharmacists, although without providing a satisfactory description. Thus, future research with more detailed description as well as an evaluation of the impact of pharmacist intervention is needed in order to guide future actions in this and/or other pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pharmacists, Pharmaceutical services, Review

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infection caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) first emerged in Wuhan (China) in December 2019, spreading rapidly across the world.1 On the 11th of March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a pandemic.2 At the time of writing there have been 10 million cases of COVID-19 reported globally, with more than 500 000 deaths reported across 216 countries.3 Currently, the COVID-19 pandemic is a major public health problem worldwide.

The most common symptoms for patients infected with COVID-19 are fever, cough, difficulty breathing, fatigue, and headache.4 Most symptomatic patients will develop mild symptoms. However, some patients may progress to serious illness, such pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, multi organ dysfunction and even death.5 So far, there are no proven effective treatments against COVID-19 and widespread effort is being devoted towards the development of a safe vaccine.3 Thus, the population must follow recommendations to decrease the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, including social distancing, wearing masks and strict hand hygiene.6

While millions of people are in their homes in order to decrease the risk of transmission of the infection, health workers are on the frontline against COVID-19.7 These professionals are committed to ensuring that the population have access to health services and to minimize the adverse impact of the pandemic. Given the seriousness of the coronavirus outbreaks, health professionals with expertise in public health are essential.

As healthcare professionals, pharmacists can play key role during the pandemic, acting directly with the community,8 continuing to care for patients with chronic diseases,9 , 10 working in hospital pharmacies and providing pharmaceutical care to COVID-19 patients.11 Moreover, they may provide reliable information for preventing, detecting, treating and managing coronavirus infections.12 , 13 As a result, several challenges have emerged and innovative strategies are being adopted by pharmacists to overcome them.14

Since the beginning of the outbreak, many guidelines have been published with recommendations for pharmacists as well as their responsibilities during the pandemic. However, few describe pharmacists' experiences in this novel context. Therefore, this scoping review is aimed to identify and describe core services provided by the pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

A scoping review was performed to explore the literature, map and summarize the evidence regarding the role of the pharmacist during COVID-19 pandemic.15 This review was conducted following the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR)16 and the review protocol registered on Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/NE2GY).

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was performed in the MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, Scopus, and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature) databases published between December 1st, 2019 (first reports of COVID-19 in China) and May 20th, 2020 in order to identify relevant studies. The search strategy included combinations of terms relating the COVID-19 and pharmacy. The full strategies search for all databases can be found in S1 Appendix. Additionally, it was conducted a grey literature search in DOAJ - Directory of Open Access Journals (https://doaj.org/) aiming to identify not indexed studies in the databases listed above. No language restriction was applied. Duplicated studies were eliminated. In addition, references cited in all included articles were reviewed to identify any studies that might have been missed.

Study selection

Studies that described services provided by the pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic were included. In addition, all publication types were eligible for inclusion. Studies that did not describe the role of the pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic; reviews, recommendations, and-or guidelines of pharmacist's role during the pandemic; presented only pharmacotherapeutic options for COVID-19; and involved graduate students were excluded.

All titles and abstracts were independently screened and selected by the authors. Full-text articles were obtained and reviewed to determine whether the article met the eligibility criteria. If the full texts of the articles were not available in the databases, the corresponding authors were contacted by email or through ResearchGate (www.researchgate.net). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

This process was performed using Rayyan QCRI, a free web application designed to help researchers working on systematic reviews.17

Data extraction and analysis

For each included study, information such as the: author, date of publication or availability online, publication type, region, workplace of the pharmacist, participants, and results summary were extracted. The pharmacist interventions reported in these studies were described based on key domains in the Descriptive Elements of Pharmacist Intervention Characterization Tool (DEPICT) version 2: 1) contact with recipient (how the contact with the recipient occurs); 2) method of communication with recipient; 3) setting of the intervention (where the recipient received the service); 4) action(s) taken by pharmacist (what is done to address the identified problems); and 5) materials that support action(s) (items developed or provided by the pharmacist as part of the service).18 The authors independently completed the data extraction, using a preformatted spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

The results of this scoping review are presented as a narrative synthesis due to the heterogeneity of the studies included. The studies were categorized according to the characteristics of the publication and summarized in tables.

Following the PRISMA-ScR,16 no quality assessment was performed due to the fact that scoping reviews aim to identify all the available evidence and highlight their main characteristics, regardless of the quality.

Results

Search results

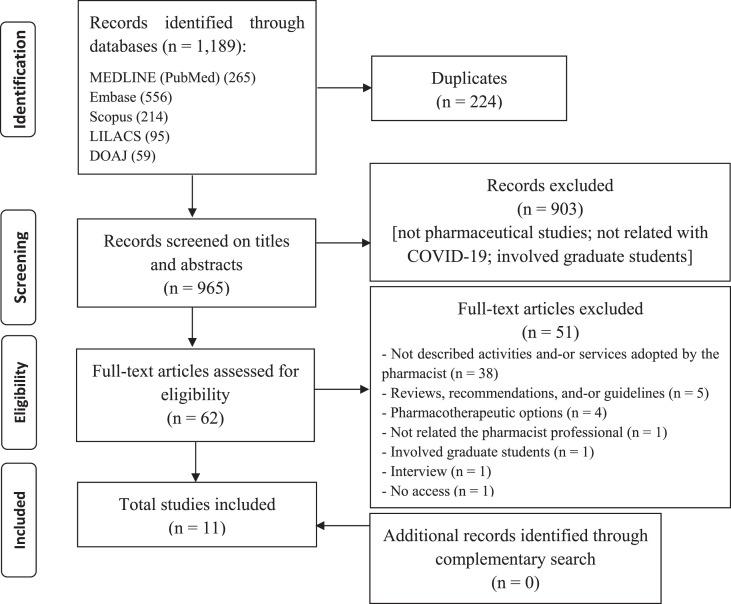

The electronic search found 1189 potentially relevant studies. After removing duplicates and reviewing the titles and abstracts, 62 articles were selected for full-text reading. In addition, no relevant studies were identified from searching the reference lists of the included studies. Of these, 11 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included for review. A flowchart of the literature search is shown in Fig. 1 . The references for the excluded studies, with the reasons for their exclusion, are available in S2 Appendix.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flowchart through literature search.

Characteristics and summary of the results of the included studies

The characteristics of the 11 studies included in this scoping review are summarized in Table 1 . Studies were conducted in the United States of America (n = 4)20,21,27,29, China (n = 4)22,23,25,28, Saudi Arabia (n = 1)19, Taiwan (n = 1)24, and Macao (n = 1).26 All studies were published in English and reported between February and May 2020. The publication type of the included studies consisted of letters (n = 4)20,21,25,27, research article (n = 2)19,22, commentary (n = 2)23,26, ideas and opinions (n = 1)24, discussion (n = 1)28, and note (n = 1)29. The majority of the studies described the workplace of the pharmacist in hospitals (n = 8)19−23,25,28,29 following the ambulatory pharmacies (n = 4)19,20,28,29, community pharmacies (n = 2)24,26, and clinic (n = 1).27 The participants of the included studies were miscellaneous, including the healthcare professionals (n = 7)19−23,28,29, COVID-19 patients (n = 5)19,22,23,28,29, general inpatient (n = 2)19,29, general population (n = 2)24,26, pediatric patients (n = 1)20, solid organ transplant patients (n = 1)21, patients on warfarin therapy (n = 1)25, and myelofibrosis patients (n = 1).27

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies in the scoping review.

| Author | Date of publication (or available online) | Publication Type | Region | Workplace of the pharmacist | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arain et al.19 | 2020 May 18 | Research article | Saudi Arabia | Hospital and ambulatory pharmacy | Healthcare professionals and COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients |

| Elson et al.20 | 2000 May 5 | Letter to the Editor | United States | Hospital and ambulatory pharmacy | Healthcare professionals and pediatric patients |

| Fan and Kamath21 | 2020 May 4 | Letter to the Editor | United States | Hospital | Healthcare professionals and solid organ transplant patients |

| Hua et al.22 | 2020 April 10 | Research article | China | Hospital | Healthcare professionals and COVID-19 patients |

| Meng et al.23 | 2020 April 2 | Commentary | China | Hospital | Healthcare professionals and COVID-19 patients |

| Ou and Yang24 | 2020 April 13 | Ideas and Opinions | Taiwan | Community pharmacy | Taiwan's population |

| Tan et al.25 | 2020 May 13 | Letter | China | Hospital | Patients on warfarin therapy |

| Ung26 | 2020 February 12 | Commentary | Macao | Community pharmacy | Macao's population |

| Yemm et al.27 | 2020 May 14 | Letter to the Editor | United States | Clinic | Myelofibrosis patients |

| Ying et al.28 | 2020 April 6 | Discussion | China | Hospital and ambulatory pharmacy | Healthcare professionals and COVID-19 patients |

| Zuckerman et al.29 | 2020 May 16 | Note | United States | Hospital and ambulatory pharmacy | Healthcare professionals and COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients |

Abbreviation: COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019).

Table 2 shows a summary of the results of the included studies. All described actions taken by the pharmacist. However, only one study evaluated the outcomes associated with pharmacist intervention.22 Several services were related in these studies, including disease prevention and infection control19 , 23 , 24 , 28 (e.g., distribution of the masks, develop hygiene strategies, discard all unused drugs dispensed for COVID-19 patients, and social distancing), adequate storage and drug supply19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 28 (e.g., drug formulary for treatment of COVID-19 to guide the drug supply and purchase, conversion of intravenous to oral medications when it was possible, and virtual communication for supply inventory), and patient care and support for healthcare professionals19, 20, 21, 22, 23 , 25 , 27, 28, 29 (e.g., ensure appropriate drug utilization for patients and healthcare professionals, participation of virtual rounds with interdisciplinary team, review online of the electronic orders, patient education, virtual medication consultation, and medication reconciliation).

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the included studies in the scoping review.

| Author | Disease prevention and infection control | Adequate storage and drug supply | Patient care and support for healthcare professionals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arain et al.19 | Decrease the visits to the pharmacy area by colleagues from other units, encouraging them to use phones or in-basket messages from the computerized physician order entry system to communicate; change of staff plan; implementation of system changes in perioperative areas; utilization of automation to reduce traffic of pharmacy staff in the hospital; discard of all unused medications dispensed for COVID-19 patients; floor markings on the ground to section areas of the pharmacy that patients can stand in while waiting or being helped. | Switch of intravenous to oral medications and intravenous infusion to intravenous push to prevent drug shortages; management of drug stocks using therapeutic interchange; communication with the supply team about adequate supplies of medications. | Participation in the development of a COVID-19 protocol; conduction of clinical interventions; monitoring and prevention of drug-drug interactions and ADR; updating pharmacy professionals about new scientific research |

| Elson et al.20 | NR | Contribution with medication access by making telephone calls to outside pharmacies, insurance companies, and patients or families. | Participation in interdisciplinary inpatient rounds using Microsoft Teams; conduction patient profile reviews to assess the safety and efficacy of medication therapy using secure remote access to patient information in the EMR; providing patient education and counseling via telephone and Microsoft Teams; continuation of quality improvement projects, formulary and inventory management, and research by conference calls, email, and telephone communication as well as Microsoft Teams and other video conferencing platforms; providing ambulatory care services remotely. |

| Fan and Kamath21 | NR | NR | Providing medication recommendations during virtual rounds with HCP; providing remote education for the patients to assist their learning of medications and lifestyle choices in discharge or admission. |

| Hua et al.22 | NR | Drug formulary and purchase, storage, and distribution of drugs; critical care trolleys loaded with all kinds of critical care drugs. | Online review of 20 000 electronic orders; providing online medication consultation for 484 patients using WeChat; providing medication and health education in the WeChat group; use a module radio station to inform the patients about the medication, rational nutrition and diet suggestions for COVID-19, and self-protection and medication guidance after discharge. |

| Meng et al.23 | Change in mode of drug delivery. | Establishing pharmacies from grounds up, including locating the ideal pharmacy location and procuring necessary equipment; compiling drug formulary; cataloging and stocking formulary drugs; resolving drug shortages. | Development of a medicinal dictionary for formulary drugs to be docked into the CDS to provide prescribing support; education for patients on medications taken at the hospital and upon discharge; providing drug information to physicians especially concerning drugs that general practitioners are not familiar with a focus on off-label drug use, and interactions between TCMs and western medicines; medication reconciliation to ensure the safe transition of care. |

| Ou and Yang24 | Repacking of bulk packages of masks into unit packets containing the rationed amount and distributed them for residents in their communities; education and consultation on proper hygiene strategies; disseminating of accurate information to counter myths and misinformation; and providing of emotional support to alleviate public concerns arising from the COVID-19 crisis. | NR | NR |

| Tan et al25 | NR | NR | Managing and providing recommendations on warfarin dose adjustment to 500 patients via a mobile phone app |

| Ung26 | Help consumers differentiate surgical masks from other types of face masks not made for protection against virus transmission; price control of surgical masks within reasonable price range and implementing “The Guaranteed Mask Supply for Macao Residents Scheme” in response to the new government policy | NR | NR |

| Yemm et al27 | NR | NR | Application of MPN-SAF TSS and the DIPSS plus via telephone and upload this information to the EMR prior to the patient's next visit. |

| Ying et al28 | Designing safety transfer devices to avoid contacting patients in drugs dispensing; adjusting the route and time of drug transportation in the hospital and using designated elevators and vehicles for drug delivery; publicized the prevention and control of COVID-19 to the public free of charge online. | Establishing a list of COVID-19 therapeutic drugs to control drug supply schemes; implementing online drug procurement; managing donated medicine. | Monitoring ADR and providing ADR information; participating in the multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 patients; participating in multidisciplinary consultations; monitoring drug interactions, implementing remote pharmaceutical services; caring out medication review. |

| Zuckerman et al.29 | Staff redeployment and staffing modifications; sourcing and using of PPE; installation of hand-sanitizing stations and plexiglass dividers in pharmacies. | Developing a list of medications required for treatment of COVID-19 patients to guide the drug supply and calculating medication quantities to purchase; developing new medication and supply storage and delivery mechanisms; creation of a virtual dashboard to clearly communicate current strategic supply inventory. | Participating in virtual meetings and inpatient rounds; patient counseling via smartphones or telehealth visits; participating of the COVID-19 pharmacotherapy working group that provided initial treatment recommendations published weekly on institutions intranet; developing of a guidance for patients receiving biologics who were at risk for COVID-19 acquisition due to immunosuppression so that providers could advise them to suspend therapy if necessary; coordinated many patients' transition from infusions to self-administered medications. |

Abbreviation: ADR (adverse drug reaction), CDS (clinical decision support system), COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), DIPSS plus (Dynamic International Prognostic Scoring System), EMR (Electronic Medical Record), HCP (healthcare professionals), NR (not reported), PPE (personal protective equipment), MPN-SAF TSS (Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Symptom Assessment Form total symptom score), TCM (traditional chinese medicine).

Characteristics of pharmacist interventions based on DEPICT 2

Studies were conducted for healthcare professionals and patients (n = 7)19−23,28,29 or only patients (n = 2).25 , 27 Two studies24 , 26 were conducted for the general population and, therefore, were classified as “not applicable”. All studies performed one-to-one contact with the recipients and six studies19, 20, 21, 22 , 28 , 29 also used the group contact. Different methods of communication were reported, including face-to-face (n = 4)19,24,26,28, written (n = 5)19,20,22,28,29, telephone (n = 6)19,20,22,23,27,29, video conference (n = 5)20−23,29 and radio station.22 One study25 did not describe how the communication with the recipient has been performed. The studies were conducted at different setting of intervention, such as hospital bedside (n = 7)19−23,28,29, hospital pharmacy (n = 2)19,29, community pharmacy (n = 2)24,26, ambulatory (n = 4)19,20,28,29, and recipient's home (n = 5).20 , 21 , 25 , 27 , 29

Pharmacists had an important role in taking actions to address during the COVID-19 pandemic, including drug information for healthcare professionals (n = 7)19−23,28,29, patient counseling (n = 8)19−23,25,28,29, suggestion for change in therapy (n = 3)19,25,29, monitoring results report (n = 1)19, drug supply management (n = 6)19,20,22,23,28,29, safety measures for infection control (n = 4)19,24,26,29, and application of tools to evaluated a disease (n = 1).27 Regarding the materials that support actions adopted by pharmacists, most studies (n = 7)20−22,24−27 did not report them. Among those that described support resources provided by the pharmacists, educational materials (n = 4)19,23,28,29 were the most reported, following the protocols (n = 2)19,29, discharge letter (n = 1)19, and safety alert system (n = 1).19 The description of the pharmacist interventions according to DEPICT version 2 are shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Description of the pharmacist interventions according to the DEPICT version 2.

| Author | Recipient | Contact with recipient | Methods of communication | Setting of the intervention | Action(s) taken by pharmacist | Materials that support action(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arain et al.19 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient and HCP) and group (HCP) | Face-to-face (patient and HCP), written (patient and HCP), and telephone (HCP) | Hospital bedside (patient and HCP), hospital pharmacy (HCP), and ambulatory setting (patient) | Drug information for HCP; patient counseling; suggestion for change in therapy; monitoring results report; drug supply management; safety measures for infection control | Discharge letter; educational materials; protocol; safety alert system |

| Elson et al.20 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient) and group (HCP) | Written (patient and HCP), telephone (patient and HCP), and video conference (patient and HCP) | Hospital bedside (patients and HCP), ambulatory setting (patient), and recipient's home (patient) | Drug information for HCP; patient counseling; drug supply management | NR |

| Fan and Kamath21 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient) and group (HCP) | Video conference (patient and HCP) | Hospital bedside (patients and HCP) and recipient's home (patient) | Drug information for HCP; patient counseling | NR |

| Hua et al.22 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient and HCP) and group (patient) | Written (patient and HCP), telephone (patient), video conference (patient), and radio station (patient) | Hospital bedside (patient and HCP) | Drug information for HCP; patient counseling; drug supply management | NR |

| Meng et al.23 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient and HCP) | Telephone and video conference (patient and HCP) | Hospital bedside (patient and HCP) | Drug information for HCP; patient counseling; drug supply management; safety measures for infection control | Educational materials |

| Ou and Yang24 | NAa | One-to-one | Face-to-face | Community pharmacy | Safety measures for infection control | NR |

| Tan et al.25 | Patient | One-to-one | NR | Recipient's home | Patient counseling; suggestion for change in therapy | NR |

| Ung26 | NAa | One-to-one | Face-to-face | Community pharmacy | Safety measures for infection control | NR |

| Yemm et al.27 | Patient | One-to-one | Telephone | Recipient's home | Application of tools to evaluated a disease | NR |

| Ying et al.28 | Patient and HPC | One-to-one (patient and HPC) and group (HPC) | Face-to-face, written (patient and HPC) | Hospital bedside (patient and HCP) and ambulatory setting (patient and HCP) | Drug information for HPC; patient counseling; drug supply management; safety measures for infection control | Educational materials |

| Zuckerman et al.29 | Patient and HCP | One-to-one (patient and HCP) and group (HCP) | Written (patients and HCP), telephone (patients), and video conference (HCP) | Hospital bedside (patient and HCP), hospital pharmacy (HCP), ambulatory setting (patient and HCP) and recipient's home (patient) | Drug information for HPC; patient counseling; suggestion for change in therapy; drug supply management; safety measures for infection control | Educational materials; protocols |

Abbreviation: HCP (healthcare professionals), NA (not applicable), NR (not reported).

Pharmacist interventions were conducted for the general population.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This scoping review identified 11 relevant studies on the services provided by the pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to discuss this question. These results indicate that there are a reasonable number of studies on this topic in a short time of the COVID-19 pandemic, although most of them are letters to the editor and other rapid scientific communications. Moreover, most studies were conducted in the United States and Asia, particularly in the region of China. These findings were expected because this region was the first local affected by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Diversely, to our surprise, no studies were performed in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom, Italy and Spain, where the COVID-19 pandemic spread quickly in mid-March. It is important to note that most studies reported the hospital as the workplace of pharmacists. Experiences with community pharmacists should be encouraged since most of the time the community pharmacy is a first point-of-care of the patients.

In light of these findings, researchers must be engaged to design and report future studies with greater methodological rigor and more detailed description of the pharmacist interventions, in order to support and guide the actions of the pharmacists in this and-or other pandemic.

General view of the studies

Most of the studies found in this review were conducted in the United States of America and China. These countries are the second and first in the scientific publication ranking worldwide, respectively.30 Moreover, China was the first region affected by the COVID-19 infection1 and therefore first experiences were felt in this location.

Regarding the type of publication, most studies were letters and other rapid scientific communications reporting experiences. These publications did not contain details of the work experiences and are at the lowest level of evidence.31 However, considering the current pandemic, when there is a need for rapid information for activity guidelines by the pharmacists need to have quick information to guide their activities, these publications are convenient and acceptable.

The hospital was the main workplace of the pharmacist in the included studies, which was an expected result because the role of pharmacist in hospital pharmacy practice is one of the most consolidated.32 Pharmacists have a very comprehensive role within the hospital, performing from administrative activities to clinical services.33 Therefore, they must be involved with all aspects of medicines use and be accessible as a point of contact for patients and health care providers.34 As a consequence, it is more than expected that they would be on the frontline against COVID-19 pandemic and reporting on their successful experiences.

This review showed that pharmacists may play an important role during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results reported were categorized as “disease prevention and infection control”, “adequate storage and drug supply” and “patient care and support for healthcare professionals”. These categories are basically the responsibilities that International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) has stated that it would like pharmacists to have in both primary care context (i.e. community pharmacies and primary healthcare facilities) and in hospital settings.12 Other recommendations of the scientific societies are also available and can help to direct the pharmacist intervention.35, 36, 37

According to the key domains of pharmacist interventions, most studies were carried out for healthcare professionals and patients. Pharmacist-provided interventions with the recipients have been shown to improve patient outcomes and contribute to substantial healthcare savings.38 In contrast, two studies did not classify as to the recipient of the intervention because the DEPICT version 2 did not predict interventions in the general population. It is important to note that pharmacists can play a role in health education and disease prevention in various ways for the general population.39, 40, 41, 42 Moreover, the level of pharmacist-recipient interaction varied between studies. Most of them described the use of telephone, written interaction including web-based, and video conference. Studies involving the use of these methods of communication have been successful43, 44, 45 and these valuable tools may be applied in a social distancing context. In addition, one study reported that pharmacists used a hospital's radio station as a communication strategy in patients who had difficulty in dealing with available technologies, highlighting the creative character.22 Regarding the setting of intervention, most studies were performed in hospital bedside, ambulatory, and recipient's home. Pharmacist interventions were described in several settings46, 47, 48 as to improving the quality of care. Unfortunately, only two studies related the community pharmacy as the setting of intervention. A recent study discussed the role of community pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic, collecting and summarizing the experience of Chinese community pharmacies.49 It is well known that community pharmacies are an important setting of care in the COVID-19 pandemic period and further studies in this context should be encouraged.

Drug information for healthcare professionals and patient counseling were the main actions provided by the pharmacists identified in this review, similarly with other studies.48 , 50 These actions focus on enhancing the problem solving skills of the patient for the purpose of improving or maintaining the quality of life.18 In addition, other actions (drug supply management and safety measures for infection control) were also identified in some studies. Gross and MacDougall51 described these actions (e.g. planning the drug shortages and antiviral stewardship) as vital during the COVID-19 pandemic period. Moreover, the key domain “Materials that support actions” has not been reported in most studies. Among those that described these resources, most of them used educational materials. These findings are similar to a study that describes the role and impact of pharmacists in Spain.52 These resources are useful to support the pharmacy services.18 The lack of this information affected the understanding which tools were used by pharmacists in their actions.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. It is possible that some studies were missed due to not being indexed in the databases searched or being published in websites of institutions or scientific societies. Moreover, the number of publications on COVID-19 is rapidly increasing in a short time and some studies of interest available after the established search period have not been included. Finally, this review did not analyze the quality of the studies taking into account the inherent characteristic of the scoping reviews.

Conclusion

A reasonable number of studies that described the role of the pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic were found. Several methods of communication were performed in different settings of intervention. Moreover, all studies reported actions taken by pharmacists, mainly drug information and patient counseling, although description was not satisfactory. Thus, future research with more detailed description and evaluated the impact of pharmacist intervention is needed in order to guide the actions of the pharmacists in this and-or other pandemic.

Authors' contributions

MBV and TML identified the reports in the databases and collected data of the studies included. MBV and TML drafted the manuscript. IVF revised for finalization of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Source of funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 52. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200312-sitrep-52-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=e2bfc9c0_4 Available from: Accessed 07.06.20.

- 3.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak situation. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 Available from: Accessed 30.06.20.

- 4.COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Symptoms of coronavirus. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/about/symptoms.html Available from: Accessed 09.06.20.

- 6.Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). How to protect yourself and others. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html Available from: Available from. Accessed 10.06.20.

- 8.Hedima E.W., Adeyemi M.S., Ikunaiye N.Y. Community Pharmacists: on the frontline of health service against COVID-19 in LMICs. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.013. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat S., Farraye F.A., Moss A. Roles of clinical pharmacists in caring for patients with inflammatory bowel disease during COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.044. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kretchy I.A., Asiedu-Danso M., Kretchy J.P. Medication management and adherence during the COVID-19 pandemic: perspectives and experiences from low-and middle-income countries. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.007. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Z., Hu Y., Zheng S., et al. Hospital pharmacists’ pharmaceutical care for hospitalized patients with COVID-19: recommendations and guidance from clinical experience. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.027. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.International Pharmaceutical Federation COVID-19: guidelines for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce. https://www.fip.org/files/content/priority-areas/coronavirus/COVID-19-Guidelines-for-pharmacists-and-the-pharmacy-workforce.pdf Available from: Accessed date: 08.06.20.

- 13.Khan Z., Muhammad K., Ahmed A., et al. Coronavirus outbreaks: prevention and management recommendations. Drugs Ther Perspect. 2020;36:215–217. doi: 10.1007/s40267-020-00717-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lia H., Zhenga S., Liua F., et al. Fighting against COVID-19: innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.003. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peters M.D.J., Godfrey C., McInerney P., et al. In: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual, JBI. Aromataris E., Munn Z., editors. 2020. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version)https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ Available from. : Accessed date: 24.05.20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., et al. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotta I., Salgado T.M., Felix D.C., et al. Ensuring consistent reporting of clinical pharmacy services to enhance reproducibility in practice: an improved version of DEPICT. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21:584–590. doi: 10.1111/jep.12339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arain S., Thalapparambath R., Al Ghamdi F.H. COVID-19 pandemic: response plan by the Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare inpatient pharmacy department. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elson E.C., Oermann C., Duehlmeyer S., et al. Use of telemedicine to provide clinical pharmacy services during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77:1005–1006. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan A., Kamath M. Comment on Gross and MacDougall ‘Roles of the clinical pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jac5.1252. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hua X., Gu M., Zeng F., et al. Pharmacy administration and pharmaceutical care practice in a module hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2020;60:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng L., Qiu F., Sun S. Providing pharmacy services at cabin hospitals at the coronavirus epicenter in China. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42:305–308. doi: 10.1007/s11096-020-01020-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ou H.T., Kao Yang Y.H. Community pharmacists in taiwan at the frontline against the novel coronavirus pandemic: gatekeepers for the rationing of personal protective equipment. Ann Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-1404. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan S.L., Zhang B.K., Xu P. Chinese pharmacists’ rapid response to the COVID-19 outbreak. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa120. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ung C.O.L. Community pharmacist in public health emergencies: quick to action against the coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16:583–586. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yemm K.E., Arnall J.R., Cowgill N.A. Necessity of Pharmacist-driven non-prescription telehealth consult services in the era of COVID-19. Am J Health Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa162. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ying W., Qian Y., Kun Z. Drugs supply and pharmaceutical care management practices at a designated hospital during the COVID-19 epidemic. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.001. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zuckerman A.D., Patel P.C., Potts A., et al. From natural disaster to pandemic: a health-system pharmacy rises to the challenge. Am J Health Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ajhp/zxaa180. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Science Foundation . National Science Foundation, EUA; 2020. Publications Output: U.S. Trends and International Comparisons (Tab. nsb20206-tabs05a-002.Xlsx). Science and Engineering Indicators.https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsb20206/publication-output-by-region-country-or-economy Available from: Accessed date: 15.06.20. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kapoor M.C. Types of studies and research design. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:626–630. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.190616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simpson S.H. The roles we have as hospital pharmacists. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2017;70:3–4. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v70i1.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chamoun N., Usta U., Karaoui L.R., et al. Current trends in hospital pharmacy practice in Lebanon. Hosp Pharm. 2020;55:112–118. doi: 10.1177/0018578718823733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Pharmaceutical Federation, Hospital Pharmacy Section Revised FIP Basel statements on the future of hospital pharmacy. www.fip.org/files/fip/FIP_BASEL_STATEMENTS_ON_THE_FUTURE_OF_HOSPITAL_PHARMACY_2015.pdf Available from: Accessed date: 17.06.20.

- 35.Sbrafh, Sociedade Brasileira de Farmácia Hospitalar . Sbrafh; São Paulo: 2020. Câmara Técnica Cuidado Farmacêutico no Enfrentamento da COVID-19 Plano de contingência em diversos cenários farmacêuticos no âmbito da pandemia por COVID-19. Sociedade Brasileira de Farmácia Hospitalar.http://www.sbrafh.org.br/inicial/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CT-Covid-19-1-1.pdf Accessed date: 18.06.20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.APhA. American Pharmacists Association . American Pharmacists Association; Washington:APhA: 2020. Pharmacists' Guide to Coronavirus.https://www.pharmacist.com/coronavirus Available from: Accessed date: 18.06.20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahmoudjafari Z., Alexander M., Roddy J., et al. American society for transplantation and cellular therapy pharmacy special interest group position statement on pharmacy practice management and clinical management for COVID-19 in hematopoietic cell transplantation and cellular therapy patients in the United States. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:1043–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dalton K., Byrne S. Role of the pharmacist in reducing healthcare costs: current insights. Integrated Pharm Res Pract. 2017;6:37–46. doi: 10.2147/IPRP.S108047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pilkington E.M. The role of the general practice pharmacist in health education and health maintenance. Health Educ J. 1979;37:187–192. doi: 10.1177/001789697803700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odedina F.T., Warrick C., Vilme H., et al. Pharmacists as health educators and risk communicators in the early detection of prostate cancer. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2008;4:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Loughlin J., Masson P., Déry V., et al. The role of community pharmacists in health education and disease prevention: a survey of their interests and needs in relation to cardiovascular disease. Prev Med. 1999;28:324–331. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lively B.T. The community pharmacist and health education. Contemp Pharm Pract. 1982;5:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shafiee Hanjani L., Caffery L.J., Freeman C.R., et al. A scoping review of the use and impact of telehealth medication reviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16:1140–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta V., Hincapie A.L., Frausto S., et al. Impact of a web-based intervention on the awareness of medication adherence. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2016;12:926–936. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fuller C.M., Turner A.K., Hernández D., et al. Attitudes toward Web application supporting pharmacist-clinician comanagement of postexposure prophylaxis patients. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2013;53:632–639. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2013.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee H., Ryu K., Sohn Y., et al. Impact on patient outcomes of pharmacist participation in multidisciplinary critical care teams: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:1243–1250. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadowski C.A., Charrois T.L., Sehn E., et al. The role and impact of the pharmacist in long-term care settings: a systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc JAPhA. 2020;60:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.japh.2019.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aguiar P.M., Brito Gde C., Lima T.M., et al. Investigating sources of heterogeneity in randomized controlled trials of the effects of pharmacist interventions on glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng S.Q., Yang L., Zhou P.X., et al. Recommendations and guidance for providing pharmaceutical care services during COVID-19 pandemic: a China perspective. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.012. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colombo L.R.P., Aguiar P.M., Lima T.M., et al. The effects of pharmacist interventions on adult outpatients with cancer: a systematic review. J Clin Pharm Therapeut. 2017;42:414–424. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gross A.E., MacDougall C. Roles of the clinical pharmacist during the COVID ‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2020;3:564–566. doi: 10.1002/jac5.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saavedra-Mitjans M., Ferrand É., Garin N., et al. Role and impact of pharmacists in Spain: a scoping review. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:1430–1442. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0740-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.