Abstract

Pharmacy schools and colleges worldwide are facing unprecedented challenges to ensuring sustainable education during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The experiences of pharmacy educators in the Asia-Pacific region in delivering emergency remote teaching, ensuring purposeful experiential placements, supporting displaced or isolated students, and communicating with faculty members, staff members, and students are discussed. The role of this pandemic in accelerating opportunities for new models of pharmacy education across the world is also discussed.

Keywords: emergency response, teaching delivery, adaptability, sustainability, teamwork

Since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus in late 2019 (COVID-19), each day has brought breaking news about the disease, updated case numbers, and intense government announcements. These stories vary by global region but suggest a united concern for health care workers, the decisions they have to make, and the availability of vital resources to support their work (eg, personal protective equipment, medications, and ventilators). Personally and professionally, pharmacy educators worldwide have cycled through periods of stress then resilience, fear then relief, pessimism then hope. We have come to realize that there is only one “known”: we cannot precisely know what will happen. An editorial by Brazeau and Romanelli advises pharmacy educators to look for opportunity and purpose amid this adversity and, in some instances, tragedy that may surround us.1

Looking for opportunity and purpose, however, requires educators to approach work differently. In schools of pharmacy worldwide, we are used to long-term planning and staged implementation of major teaching initiatives. We ask each other, “what do we want our graduates to be able to do at the end of the program?” and “How can we support the use of medicines and health technologies over the next 20 years?” The best curricular teams are full of thinkers who begin with the end in mind and then work methodically to forecast, plan, and design for the future. We equally excel at identifying best practices and productively critiquing each other’s work until it is near what we believe is perfect. However, crises like the current pandemic challenge traditional approaches to long-term planning, staged implementation, best practices, and near-perfect work. To fulfil our responsibility to each other, our students, and the patients they will serve, we must be agile and connected.

Because of COVID-19, many universities have transitioned to emergency remote delivery of courses (ie, mostly online and with no face-to-face interactions). At Monash University’s Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, we were fortunate in some aspects and challenged in others to achieve remote delivery. First, similar to other programs worldwide, we had recently undergone a curriculum transformation that included increased active learning, a focus on skill development, more experiential placements, and a required research project. Although these higher-yield learning approaches were crucial, they were more difficult than lectures to adjust quickly to remote delivery. Second, in the southern hemisphere, our first semester begins in early March. Therefore, our pharmacy students had only one day of face-to-face instruction on our campuses before the restrictions were implemented. Third, a relatively uncommon aspect of the Monash program is that we teach across two countries (Australia and Malaysia) and, hence, are governed by two professional accrediting bodies (ie, the Australian Pharmacy Council and the Malaysian Pharmacy Board). We follow a needs-based model where the unit coordinators (the equivalent of course directors in the United States) from each campus collaborate via Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, CA) to create instruction and assessments for both cohorts.2

As some have suggested that COVID-19 has turned our world “upside down,” we write this piece to share perspectives from “Down Under.” Specifically, we outline ways that we have used sustainability principles to deliver emergency remote teaching, ensure purposeful experiential placements, support displaced or isolated students, and communicate with faculty and staff members and students in the Asia-Pacific region. We also discuss how this pandemic accelerates opportunities for new models of pharmacy education across the world.

Delivering Emergency Remote Teaching

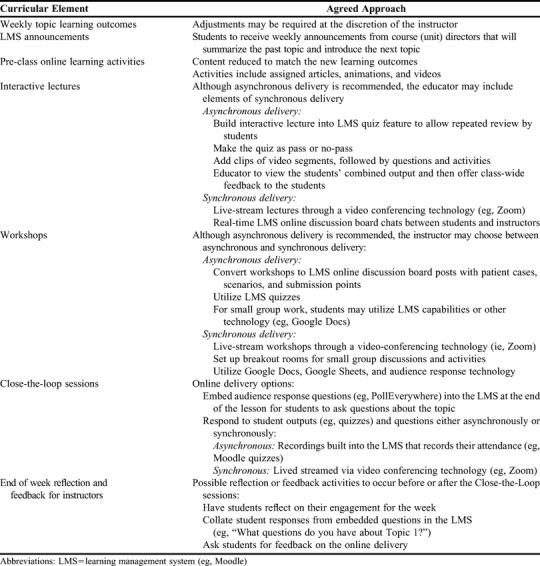

The literature is already brimming with best practices for online learning.3-5 However, because of the short timeframe for implementation, we had to use pragmatic strategies. As a first step towards rapid online delivery, our unit teams in Australia and Malaysia focused on consistency across each year of the academic program (eg, P1, P2, P3, P4) and, when possible, across the entire curriculum. By creating consistency, instructors could more easily deputize and support each other. Also, students would experience similar formats, technologies, and expectations across their classes. As shown in Table 1, we considered each curricular element (eg, lectures) and agreed on a consistent approach for how this would be delivered online.

Table 1.

Rapid Solutions to Delivering Emergency Remote Pharmacy Teaching in the Asia-Pacific Region

After prioritizing consistency, we adapted a sustainability mindset, promoting a “reduce, reuse, recycle, and renew” approach. We reduced content, learning objectives, and synchronous learning requirements. We assumed that students could acquire knowledge through online platforms. When campus-based activities return, we plan to implement an intensive period when students will master skills they were unable to demonstrate fully online (eg, extemporaneous compounding). Instructors use asynchronous learning whenever possible to be considerate of students who may be working more pharmacy shifts, have caregiver responsibilities, are ill themselves, are sharing internet bandwidth with others, or had returned to their home country in a different time zone. Moreover, synchronous learning requires more instructor time and resources because of students who may miss activities and require remediation. However, we did create some synchronous touchpoints to build community between students and instructors. For example, instructors for each of our courses walked first-year students through the overall plans for the semester via a Zoom webinar. Following this overview, instructors responded live to questions posted online during the session. Some of our previously planned workshops were reduced in content, but we delivered them synchronously to smaller groups of students. For example, we used the “breakout room” feature of Zoom and randomly sorted students into rooms of two to three to role-play patient counselling.

We reused previous lecture recordings, assessments, and learning materials. When still relevant, instructors reformatted recorded lectures from the previous year. For some of our 2019 lecture recordings, instructors cut these into segments of approximately nine minutes. They then added interactive response questions and activities in between the lecture segments. This enabled students to test and retest between the key concepts. We also reused student questions from previous clarification sessions to develop online posts with frequently asked questions.

Instructors recycled previously created assessments and material for student remediation and self-study. For example, many of our face-to-face workshops were reduced to the necessary components for students to complete online. The activities and materials that were removed from the workshops were used for student remediation and posted as optional activities (eg, practice quizzes) for students who desired more practice with the material.

Finally, our faculty members renewed their connection to crucial academic and practice partners worldwide. We reached out to our medical faculty members to align our expectations of what students could achieve online and what they needed to learn through experience. This dialogue was constructive in keeping expectations harmonized across the health professions. We prioritized interprofessional learning activities, which, despite being more logistically difficult to implement online, emphasized the very teamwork critical during a pandemic response.6 We also regularly contacted our professional bodies and practitioner partners to stay current with their needs and pressure points. Instructors renewed their commitment to building a community among our learners. For example, we hosted a virtual online welcome ceremony for our international students to help connect learners (especially those new to our university) to other students and resources. During the welcome ceremony, we discussed everything from the new delivery of learning to the cultural role of Vegemite (a food spread) and Tim Tams (a chocolate cookie) in Australia. We even developed a virtual career fair to ensure our graduating pharmacy students could connect with postgraduate internship employers (the next required step for fourth-year pharmacy students in Australia).

Ensuring Purposeful Experiential Placements

The public needs access to medicines and reliable health systems, and these needs are amplified in times of crisis. To address these needs, pharmacists in community and hospital settings are critical. In the professional oath, pharmacists are called to place the needs of others above their own interests.7 Our students are pharmacists in training who now more than ever are a critical part of health care delivery.

In response to the pressures of COVID-19, we have observed health profession schools take one of three approaches to clinical education: containment, learning, or workforce support. With a containment approach, programs remove all students from practice sites to reduce transmission risk and focus on essential services. In a learning approach, programs keep students at practice sites to participate in their usual activities or observe pandemic response activities. With a workforce support approach, programs “skill up” students to support the pandemic response activities. Examples of the workforce support approach include repurposing medication supplies from different sources, providing information to patients and caregivers, and helping to ensure medication access.

As a first step at Monash, we followed the World Health Organization (WHO), governmental, and department of health guidance. Next, we connected with medical faculty members to ascertain their approach regarding health professional students in experiential sites during the pandemic. We then connected with the professional and regulatory bodies that support pharmacy practice in Australia and Malaysia. We agreed that site-based capacities were critical considerations. Finally, we contributed to the development of guiding principles for pharmacy student clinical education during a global health emergency via the Council of Pharmacy Schools (CPS): Australia and New Zealand.8 Together, the CPS programs advocated for a workforce support approach, ie, the continuation of placements in health settings that welcomed and could safely support a workforce support approach. Through phone and email communications with our sites, we reinforced site-specific adjustments such as restricting students to specific areas or specialties. In Malaysia, however, the government-issued movement control order meant that student experiential placements for all health professional programs had to be delayed.

We had regular communications (email and via Zoom) with our final-year students who were on experiential placements during this period. These were not always easy conversations, including topics like personal health risk, cultural norms (eg, mask wearing), and professional responsibility. We endorsed three options for students: stay on placement to support the health system in somewhat altered roles; take a break from the placement temporarily with an alternate schedule for completing the placement forthcoming; or take an intermission from the degree program for this year. To support student wellbeing, we reinforced the availability of physical and mental health support services accessible free of charge and without stigma. As we were receiving increasing requests from health care settings for pharmacy students willing to take on additional support roles, we started a registry of students who were interested in volunteering for a “surge workforce.” Then, we connected with our local professional bodies and sites to support the registry. We also aligned our overall efforts with our medicine, nursing, and allied health programs, taking the approach that where other health professions students are contributing, pharmacy students should be contributing, too.9

Supporting Displaced and Isolated Students

Before the number of COVID-19 cases increased exponentially in Australia, the virus did not affect the day-to-day lives of most of our instructors and domestic students. It did, however, result in travel bans that kept many of our international students from being able to come to Australia to study. As a team, we led with empathy for what these students may have initially experienced. We encouraged all domestic students to think about what it might be like to worry about a loved one. Only a few months later, this became a shared reality. One of our first actions in establishing an online teaching and learning system for our international students was to recruit Mandarin-speaking facilitators for each of the first-year units. Although our instruction is usually delivered only in English, we thought international students would appreciate communicating the complexities of their situation and being introduced to the active-learning model in their native language.

In addition to empathy, we promoted dignity. It was necessary that these students be able to integrate with their Australian cohorts and feel like they belonged. Early in the pandemic, we emphasized to students that COVID-19 was not a “Chinese” virus and should not be described as such because such misnomers often reflect and perpetuate prejudices. Instead of referring to the students now studying from China as “COVID-impacted students,” we designated the displaced students as “Group 9” to mimic our usual student grouping structure (ie, we allocate students into one of eight workshop groups). We were delighted to learn that nine represents longevity in Chinese culture. We supported these students in this distinct way until they joined the wider cohort back in Australia, by which time, most of the program for all students had converted to online delivery.

Although online delivery of the pharmacy curriculum has allowed us to continue training future pharmacists during this crisis, there is no doubt that some access to on-campus instruction better encourages the connections students develop with their school, their peers, and what they are learning. Even in the earliest stages of this remote model of education delivery, we were hearing students grieve over the loss of casual interactions with their peers, and participating in cocurricular activities and social events. Although some students find distance education more convenient, many say it is difficult to motivate themselves to learn deeply when they lack these personal connections. Academics are mourning this as well. The memories of our collegial interactions at libraries, coffee shops, and conferences leave holes in the university experience for faculty members as well. Because of this, we are inspired by the burgeoning socialization efforts such as virtual coffee chats, happy hours, house parties, game competitions, and even formal balls.

Communicating With Faculty Members, Staff Members, and Students

Our students had many questions about the changes in the instructional models, the use of new technologies, whether they should go back to their home countries to study, and whether they should continue in the program at all. To address these systematically, our university initially chose to centralize all student communications. This is a well-founded crisis management practice designed to reduce the risk of confusion among stakeholders. Because our local instructional approach is very hands-on, however, our pharmacy academics struggled with this perceived distancing. Once decentralized communications were allowed, we sent out streamlined email announcements and recorded open-ended webinars between instructors and students. Our student liaison committee, which includes representatives from each cohort and key student organizations, continued to meet virtually. We also held weekly Zoom check-in sessions for all first-year students and Zoom SnackChat sessions for all students to mimic our usual practice of gathering for informal discussions.

To familiarize students and instructors with new technologies, we provided training and resources on adapting our virtual meeting technologies (ie, Zoom) for use in teaching. Training included functionality, etiquette for video conference calls, and recorded examples. Instructors assisted each other in conducting pilot tests of new teaching formats. We created a special section for COVID-19 adjustments on the Education Community of Practice housed on our learning management system (ie, Moodle).

Faculty and staff members received regular email updates from university and faculty leadership. The latter were particularly important, as university-wide messages can never fully capture all faculty-specific issues in the midst of a rapidly evolving crisis. Moreover, it is common in these situations for stakeholders to experience “message fatigue.” Faculty and staff members are more likely to respond to targeted communications that reiterate and/or contextualize university communications. Our dean emphasized the programmatic need to deliver on our mission of high-quality education and research, while ensuring workforce safety and sustainability. In brief, the goal was to focus on the “Three L’s”: lives, livelihoods, and learning. We utilized social media to showcase how our education was being delivered and to normalize our approach. Our leadership acknowledged publicly that changes would require reprioritization of our normal activities to ensure that we maintain our operations without compromising student and staff health. This meant that we postponed some events and initiatives because academics were contending with substantial changes to the way education was delivered and research was conducted. Most importantly, we provided flexibility to faculty and staff members to fulfil their roles. Each staff member worked with their supervisor to address their concerns and tailor a flexible working arrangement.

Accelerating Opportunities for New Models of Education

When the COVID-19 crisis abates, education and health care will be forever altered. Academic leaders, instructors, and students will be changed. Perceptions of geographic borders will be changed. This is not unlike how we had already been seeing our health care systems change. In fact, initiatives previously predicted to take decades were implemented in a matter of days. In Australia, restrictions to telemedicine and electronic prescribing were removed overnight. Almost daily, the Australian government announced new funding streams that affect health care, eg, an outpouring of funding for telemedicine, free childcare for health care workers, greater backing for mental health support, and more. Likewise, the customary understanding of our academic workplaces will be changed. Managers will be more comfortable with academics working from home. This will likely extend beyond education to biomedical research. Instructors will be more comfortable with a variety of technological platforms. Researchers will see the emergence of completely new industries, which has often been the case after an economic recession or depression.

This article describes the efforts of academics, practitioners, and students in one university across two countries in the Asia-Pacific region adjusting rapidly to the educational challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some of what we at Monash University have experienced during this pandemic may be different from the realities faced by universities in other parts of the world. However, despite the geographic distance between us, we suspect much of what we have described will ring true, particularly with other pharmacy educators. Although we have set aside some of our academic traditions to deal with the acute phase of the pandemic, our strength as long-term planners will be critical as we enter the chronic phase. To forge a sustainable future in health care, pharmacy educators must reduce, reuse, recycle, and most importantly, renew. Indeed, this experience has amplified the need for schools and colleges of pharmacy worldwide to work together. It may also accelerate motivation within pharmacy education to endorse global curricula the way other health professions are considering.10 Regardless of region, we have a collective responsibility to prepare pharmacy students to be practice-ready and team-ready for now and for the next global pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge all pharmacy unit coordinators, instructors, teaching associates, preceptors, educational designers, professional staff, and research staff in Australia and Malaysia who have contributed to this implementation. We also thank our students for partnering with us in these efforts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brazeau G, Romanelli F. Navigating the uncharted waters in the time of COVID-19. Am J Pharm Educ. 2020;84(3):Article 8063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson C, Bates I, Beck D, et al. . The WHO UNESCO FIP pharmacy education taskforce. Hum Resour Health. 2009;45(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volery T, Lord D. Critical success factors in online education. Int J Educ Manag. 2000;14:216-223. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Means B, Bakia M, Murphy R. Learning Online: What Research Tells Us About Whether, When and How. New York, NY:Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Neill K, Singh G, O’Donoghue. Implementing eLearning programmes for higher education: a review of the literature. J Inf Technol Educ Res. 2004;3(1):313-323. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kent F, George J, Lindley J, Brock T. Virtual workshops to preserve interprofessional collaboration while physical distancing [published online ahead of print April 2020]. Med Educ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Oath of a Pharmacist. International Pharmaceutical Federation. https://www.fip.org/files/fip/FIP_Pharmacist_oath_A4_with_signature.pdf. Adopted August 31, 2014. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 8.Council of Pharmacy Schools: Australia and New Zealand. Guiding principles for pharmacy student clinical education during a global health emergency. https://www.pharmacycouncil.org.au/news-publications/news/200424-cps-guiding-principles-for-clinical-education.pdf. Published April 24, 2020. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 9.Dooley M. Thank you on behalf of the JPPR. J Pharm Prac Res. 2020;50:117-121. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giuliani M, Martimianakis MA, Broadhurst M, et al. Motivations for and challenges in the development of a global medical curricula [published online ahead of print April 2020]. Acad Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]