Abstract

During times of stress, such as those experienced during the novel coronavirus identified in 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, pharmacy students handle the experience differently. For some, the experience may negatively impact their sense of well-being; for others, being at home with family could actually improve their well-being. While students are completing academic work at home and after they finally return to campus, pharmacy schools need to be keenly aware of students’ experiences and implement strategies to build their resilience and improve their well-being. One approach will not meet the needs of all students. Many of the challenges that pharmacy students have faced or will face when they return to the classroom are discussed along with some programs and activities that have proven successful.

Keywords: well-being, resilience, COVID-19

INTRODUCTION

A common educational adage reminds us, “students must Maslow before they can Bloom.” According to Abraham Maslow, humans are motivated by eight hierarchical needs, with the more basic levels needing to be met prior to focusing on higher needs.1 These needs include: physiological needs, safety needs, belonging and love needs, esteem needs, cognitive needs, aesthetic needs, self-actualization, and transcendence. Maslow felt that if a need is not sufficiently met, the motivation to fulfill such a need will become stronger the longer it remains unmet.1 Major traumatic and stressful events such as those associated with the COVID-19 pandemic can increase the strains on college students who are still undergoing identity development.2 Some students may be facing unmet physiological, psychological, and safety needs, possibly in areas in which they have not previously experienced a deficiency. When these needs go unmet, students will struggle to focus on, never mind excel at, their academics. Personal well-being, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “the presence of positive emotion and moods (eg, contentment, happiness), the absence of negative emotions (eg, depression, anxiety), and satisfaction with life, fulfillment, and positive functioning,” will be negatively impacted.3 In turn, this makes the ability to maintain or recover mental health after experiencing adversity (ie, resilience) that much more important.4

The significant economic impact of COVID-19 resulting from stay-at-home orders, business closures, and layoffs has led to a deficiency in fulfillment of physiological needs for some students. They have concerns over food and shelter, caused by the loss of their own or their parents’ income. Simply moving out of the residence hall of the school where they were enrolled created a physiological need for some because they no longer have access to dining halls or a safe environment. Others who were allowed to remain in their residential hall or were living in a nearby apartment may no longer feel safe to go to the grocery store, a restaurant, or the dining hall to obtain food.

Some students may be experiencing a deficiency in safety needs due to insecurity, fear, and prolonged uncertainty about becoming infected, caring for sick family members, or being able to afford school, conduct research, or return to campus in the fall. In an April 2020 study published in Inside Higher Ed, 26% of college students reported being unlikely to return or unsure about whether they would return to their current college in the fall.5 Minority students may be particularly impacted, with 64% reporting their plans have been affected by the pandemic, in contrast to 44% of white students. Additionally, 10% of college-bound seniors who originally planned to enter college have already made alternative plans, with 41% of minority high school seniors reporting it is unlikely they will attend college this fall.5 Students’ concerns about their own and their family’s safety may also be taking a toll. Students may be homeschooling young children or questioning how they will be able to attend school or work if their children do not return to school. Some graduate students are fearful for their safety because they are being required to conduct laboratory experiments on campus during the pandemic. Professional program students may be questioning if they are prepared to be members of a health profession working on the front lines. International students who left the United States are uncertain when travel restrictions will be lifted, while those who remained in the United States may feel pressure from their families or government to return home.

While the United States has not yet experienced the full psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the experience in Asia provides us with insights into what the impact might be. Wang and colleagues’ study of more than 1200 members of the general population in China found 53.8% of respondents rated the psychological impact of the epidemic as moderate or severe.6 More than 16% reported having moderate to severe depressive symptoms, while 28.8% reported having moderate to severe anxiety symptoms and 8.1% reported having moderate to severe stress levels. Female gender, student status, and poor self-rated health status were associated with significantly higher psychological impact and higher levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. A study by Li and colleagues evaluated the vicarious traumatization scores of the general public, non-front-line nurses, and nurses working with COVID-19 patients. Li and colleagues found non-front-line nurses and the general public had significantly more severe vicarious traumatization than that observed in nurses working with COVID-19 patients.7 While it is unknown why the general public experienced more significant traumatization than front-line nurses, this traumatization may be due to insufficient understanding of the situation or mixed or limited messages from the media. In Liang and colleagues’ study of 584 youth in China after the worst of the pandemic had ended, more than 14% of the surveyed youth exhibited post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.8 In Cao and colleagues’ study of more than 7000 students from Changzhi Medical College, 24.3% of students were experiencing anxiety.9 These results strongly suggest that the well-being of a significant percentage of students around the world may be negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

During times of uncertainty or threat, or when information is lacking, the limbic system and autonomic nervous system take control of the brain, leading to a more emotional response. When the amygdala becomes hyperactive, stress hormones are released, leading to a fight, flight, or freeze response, impairing our ability to pay attention, make decisions, and learn. For some previously campus-based students, having to participate in distance learning to complete the spring 2020 semester of the PharmD program was not an easy undertaking. Some students who were forced to return to their home located in another time zone spent the semester listening to synchronous lectures and taking examinations in the middle of the night, being alone on campus because they had no other home, participating in class from their car to use the wi-fi at the local library, or even while listening to ambulances racing critically ill patients to the hospital day and night.

For some, the sudden change to remote teaching presented another set of academic challenges. Students were subject to the varied teaching decisions of each faculty member. Faculty opted to utilize a variety of technology platforms for teaching synchronously or asynchronously. Because of the lack of preparation time for this new mode of delivery, faculty members may not have considered the accessibility and accommodation needs of some students, thereby leaving visually impaired, hard of hearing, English language learners, and others at a disadvantage. International students in different time zones may have experienced frustration when required to participate in synchronous learning activities. Additionally, students who returned to countries with internet censorship were challenged daily with finding ways to access online resources. All of these academic challenges could lead students to feel a loss of independence and sudden inability to master material they might have easily comprehended under more normal circumstances.

Another challenge that both faculty members and students have experienced during stay-at-home orders is isolation, which can lead to a deficiency in a feeling loved and sense of belonging.10 Even though we often see colleagues and students virtually throughout the day, the virtual environment allows only limited, artificial human interaction and creates a form of anxiety referred to as “Zoom fatigue.”11 The isolation that many students are experiencing during the pandemic also creates a less complex cognitive representation of self. This less complex representation is associated with increased mood swings, while increase in self-complexity serves as a buffer against the negative impact of stressful events.12 Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 35% of first-year college students had reported being diagnosed with an anxiety, mood, or substance disorder, and some of these students may experience an exacerbation of symptoms as a result of the isolation resulting from stay-at-home orders.13

Institutional Support of Student Well-Being

Every institution needs to confront the issues affecting their students’ well-being and academic health. We should demonstrate concern for students but not send additional cues and signals that could exacerbate their anxiety. Schools should also remember that not all students are responding to the pandemic in the same way.14 This is because each person has a unique set of resilience factors that becomes particularly apparent during disasters and traumatic events, including personality traits, attributional style, social support system, and coping self-efficacy.15,16 Some students have actually performed better at home than they did when they were away at school. For these students, the comfort of being with family, only needing to focus on learning without juggling other responsibilities, making time for exercise, spending more time on hobbies, or maintaining a healthy lifestyle creates an environment for success. Some students may prefer the flexibility of asynchronous online learning, which eliminates the need for alarms and leads to better sleep and overall well-being.

A 2019 statement from the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy prompted many conversations around the responsibility of pharmacy programs for the overall development and support of student well-being.17 Research conducted among pharmacy and other professional students demonstrated the effectiveness of interventions such as yoga, meditation, mindfulness, adequate sleep, expression of gratitude, social relationships, and exercise on improving the aspects of well-being.18-23 Strategies to encourage students to develop and sustain such behaviors range from role-modeling to intentionally incorporating well-being challenges as part of a course.24,25

While there is no evidence that any specific type of intervention increases the resilience of professional students, schools can help students to understand and develop protective factors that positively influence resilience.4 Programs can support student resilience through building positive professional relationships and networks with students and faculty and staff members, maintaining positivity, helping students develop emotional insight, achieving life balance, and becoming more reflective.4

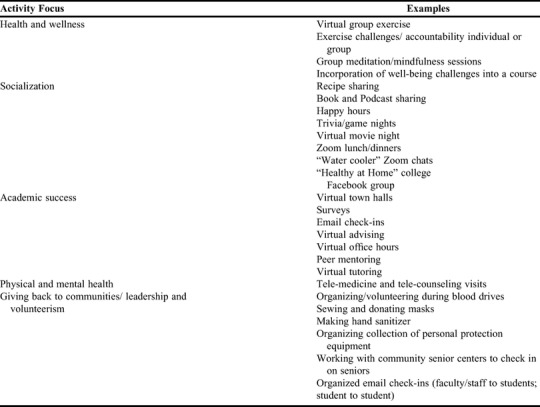

During the 2020 spring semester, we learned that many strategies to improve students’ well-being during stressful times like the COVID-19 pandemic can be supported in an online remote environment. However, there is no one-size-fits-all approach for improving the well-being of pharmacy students as the needs of each student will vary. In Table 1, the authors provide examples from their own institutions that programs can use to determine what is feasible to implement for their school. Many programs may already have one or more of these approaches in place but may wish to consider adding new strategies that will complement them. Providing support to students during these times should be a priority and a shared responsibility of administrators, faculty and staff members, and students. Professional student organizations could lead many of these initiatives. Identifying and recruiting students and faculty and staff members to champion these programs can decrease the burden on any one individual as well as provide different perspectives. Coordination of available options and activities can help maintain the balance and variety of the types of support available to students without overwhelming them. Throughout these activities, reinforcing the concept of resilience and how students can maintain well-being during these times of adversity can help prepare students for the post-COVID-19 world.

Table 1.

Activities and Services That Schools Can Implement to Provide Support to Doctor of Pharmacy Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic

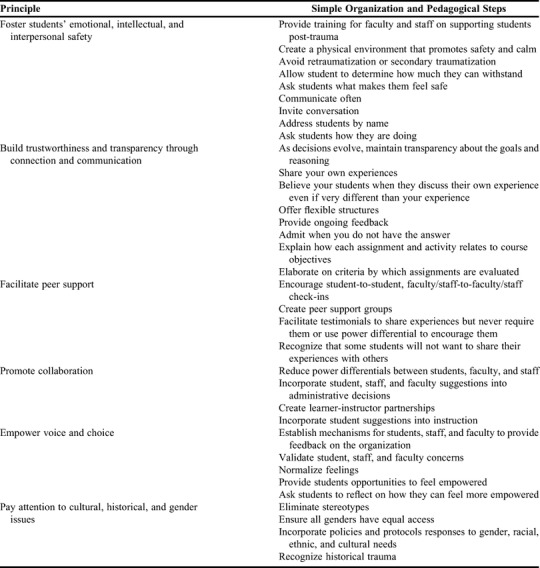

As institutions continue to develop plans for the fall semester, schools should also begin considering how to assist students with the potential trauma induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The long-term effects of trauma can lead to an inability to cope with normal stress, cognitively process information, regulate behavior, and/or control emotions.26 Schools should provide programs to facilitate students’ recovery and strengthen their resilience, and ensure a trauma-informed approach to developing these programs by embracing the six guiding principles of the US Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA).26 Faculty and staff members do not have to be experts in trauma care to incorporate the SAMHSA principles into their organizational and pedagogical activities, and simple steps are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Six Guiding Principles26 to a Trauma-informed Approach and Potential Application in Pharmacy Schools

CONCLUSION

When faculty members and students finally return to campus, schools will need to remain keenly aware of students’ experiences. Just as our daily lives may not return to the normal we knew, some students may return to campus changed from the people they were when they left (some for better and some for worse). Programs should implement and maintain strategies to build students’ resilience and improve their well-being, realizing that any one approach will not meet the needs of all students.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maslow AH. Motivation and personality. 3rd ed. Delhi, India: Pearson Education;1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shalka TR. Saplings in the hurricane: a grounded theory of college trauma and identify development. Rev Higher Educ 2019:42(2): 739-764. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL). Published 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/wellbeing.htm. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 4.Stoffel JM, Cain J. Review of grit and resilience literature within health professions education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82(2):Article 6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaschik S. Colleges could lose 20% of students. Inside Higher Ed website. https://www.insidehighered.com/admissions/article/2020/04/29/colleges-could-lose-20-percent-students-analysis-says. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 6.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z, Ge J, Yang M, et al. Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non-members of medical teams aiding in COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. 2020.doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liang L, Ren H, Cao R, et al. The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly 2020. doi.org/ 10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatric Research 2020;287. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.House JS. Social isolation kills, but how and why? Psychosomatic Medicine 2001;63:273-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sklar J. ‘Zoom Fatigue’ is taxing the brain. Here’s why that happens. National Geographic website. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/04/coronavirus-zoom-fatigue-is-taxing-the-brain-here-is-why-that-happens/ Accessed April 24, 2020.

- 12.Linville PW. Self-complexity and affective extremity: don't put all of your eggs in one cognitive basket. Social Cognition. 1985;3(1):94-120. 10.1521/soco.1985.3.1.94 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Cuijpers P, et al. WHO World mental health surveys international college student project: prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnormal Psych . 2018;127(7):623-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson PJ, Brymer MJ, Bonanno GA. Postdisaster psychological intervention since 9/11. Am Psych . 2011;66(6):482-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonanno GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, LaGreca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster: consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychol Sci Public Interest . 2010;11(1):1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neria Y, Wickramaratne P, Olfson M, et al. Mental and physical health consequences of the 9/11 attacks in primary care: longitudinal study. J Traumatic Stress . 2013;26:45-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. AACP Statement on Commitment to Clinician Well-being and Resilience. https://www.aacp.org/article/commitment-clinician-well-being-and-resilience. Accessed April 13, 2020.

- 18.Lemay V, Hoolahan J, Buchanan A. Impact of a yoga and meditation intervention on students' stress and anxiety levels. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019;83(5):Article 7001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zollars I, Poirier TI, Pailden J. Effects of mindfulness meditation on mindfulness, mental well-being, and perceived stress. Curr Pharm Teach Learn . 2019;11(10):1022-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Driscoll M, Sahm LJ, Byrne H, Lambert S, Byrne S. Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on undergraduate pharmacy students' stress and distress: Quantitative results of a mixed-methods study. Curr Pharm Teach Learn . 2019;11(9):876-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skead N, Rogers SL. Stress, anxiety and depression in law students: how student behaviors affect student wellbeing. Monash UL Rev . 2014;40(2):565-588. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf MR, Rosenstock JB. Inadequate sleep and exercise associated with burnout and depression among medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):174-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Layous K, Chancellor J, Lyubomirsky S. Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123(1):3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory DF, Boje KM, Carter RA, et al. Leading change in academic pharmacy: report of the 2018-2019 AACP Academic Affairs Committee. Am J Pharm Educ . 2019; 83(10):Article 7661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cain J. Effectiveness of well-being challenges to nudge students to adopt well-being protective behaviors. Am J Pharm Educ. ePublished February 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. Substance abuse and mental health services administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. 2014. http://www.hmprg.org/wp-content/themes/HMPRG/backup/ACEs/Handouts_Merged%20Final.pdf Accessed April 30, 2020.